Pliocene Marine Bivalvia from Vale Farpado (Pombal, Portugal): Palaeoenvironmental and Palaecological Significance

Abstract

1. Introduction

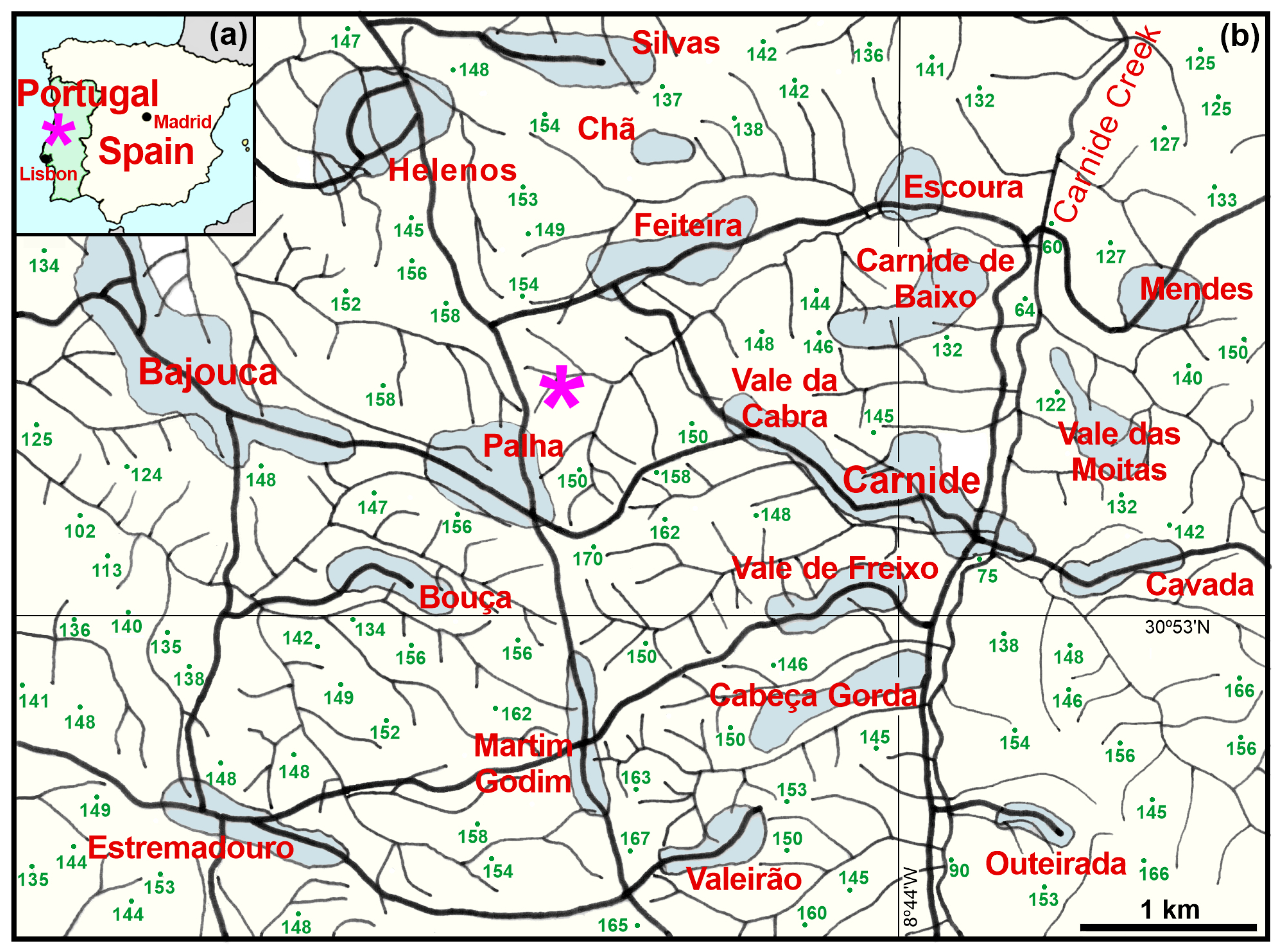

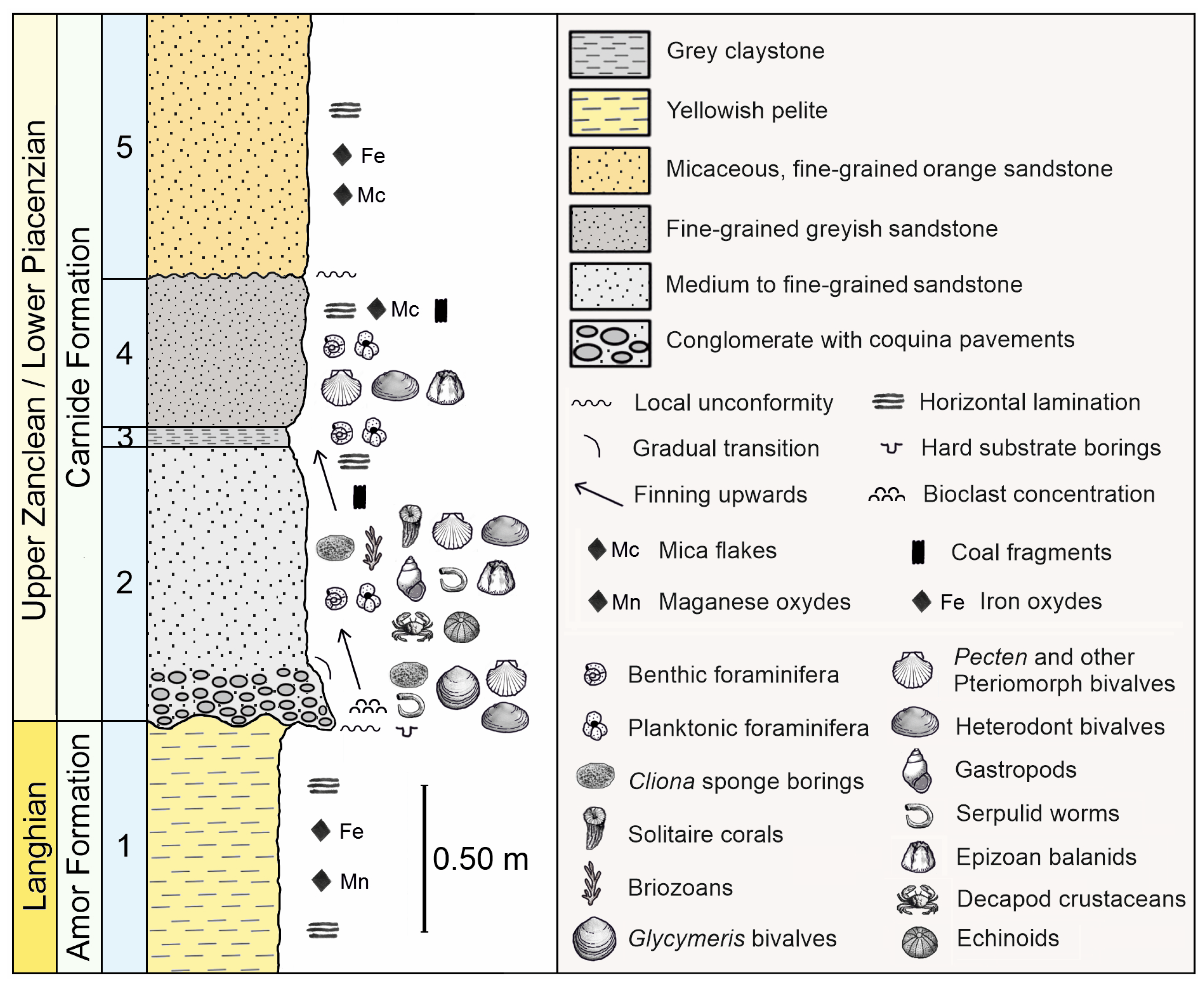

2. Geographical and Stratigraphical Settings

3. Material and Methods

4. Systematic Palaeontology

| Class: Bivalvia Linnaeus, 1758 [69] Subclass: Protobranchia Pelseneer, 1889 [70] Order: Nuculida Dall, 1889 [71] Superfamily: Nuculoidea Gray, 1824 [72] Family: Nuculidae Gray, 1824 [72] Genus Ennucula Iredale, 1931 [73] Ennucula laevigata (J. Sowerby, 1818) [74] Genus: Nucula Lamarck, 1799 [75] Nucula nucleus (Linnaeus, 1758) [69] Order: Nuculanida J.G. Carter, D.C. Campbell and M.R. Campbell, 2000 [76] Superfamily: Nuculanoidea H. Adams and A. Adams, 1858 [77] Family: Nuculanidae H. Adams and A. Adams, 1858 [77] Genus: Lembulus Risso, 1826 [78] Lembulus pella (Linnaeus, 1758) [69] Subclass: Autobranchia Grobben, 1894 [79] Infraclass: Pteriomorphia Beurlen, 1944 [80] Order: Arcida Stoliczka, 1871 [81] Superfamily: Arcoidea Lamarck, 1809 [82] Family: Noetiidae Stewart, 1930 [83] Genus: Striarca Conrad, 1862 [84] Striarca lactea (Linnaeus, 1758) [69] Family: Glycymerididae Dall, 1908 [85] Subfamily: Glycymeridinae Dall, 1908 [85] Genus: Glycymeris da Costa, 1778 [86] Glycymeris glycymeris (Linnaeus, 1758) [69] Order: Ostreida Férussac, 1822 [87] Superfamily: Ostreoidea Rafinesque, 1815 [88] Family: Ostreidae Rafinesque, 1815 [88] Subfamily: Ostreinae Rafinesque, 1815 [88] Genus: Ostrea Linnaeus, 1758 [69] Ostrea edulis Linnaeus, 1758 [69] Order: Pectinida Gray, 1854 [89] Superfamily: Pectinoidea Rafinesque, 1815 [88] Family: Pectinidae Rafinesque, 1815 [88] Subfamily: Pectininae Rafinesque, 1815 [88] Genus: Flexopecten Sacco, 1897 [59] Flexopecten flexuosus (Poli, 1795) [90] Genus: Pecten O.F. Müller, 1776 [91] Pecten benedictus Lamarck, 1819 [92] Subfamily: Palliolinae Korobkov in Eberzin, 1960 [93] Genus: Lissochlamys Sacco, 1897 [59] Lissochlamys excisa (Bronn, 1831) [25] Subfamily: Pedinae Bronn, 1862 [94] Genus: Mimachlamys Iredale, 1929 [95] Mimachlamys varia (Linnaeus, 1758) [69] Superfamily: Anomioidea Rafinesque, 1815 [88] Family: Anomiidae Rafinesque, 1815 [88] Genus: Heteranomia Winckworth, 1922 [96] Heteranomia squamula (Linnaeus, 1758) [69] Genus: Pododesmus Philippi, 1837 [97] Pododesmus squama (Gmelin, 1791) [98] Infraclass: Heteroconchia Hertwig, 1895 [99] Superorder: Imparidentia Bieler, Mikkelsen and Giribet in Bieler et al., 2014 [42] Order: Carditida Dall, 1889 [71] Superfamily: Crassatelloidea Férussac, 1822 [87] Family: Astartidae d’Orbigny, 1844 [100] Genus: Digitaria S.V. Wood, 1853 [101] Digitaria digitaria (Linnaeus, 1758) [69] Genus: Laevastarte Hinsch, 1952 [102] Laevastarte fusca (Poli, 1791) [103] Superfamily: Carditoidea Férussac, 1822 [87] Family: Carditidae Férussac, 1822 [87] Subfamily: Venericardiinae Chavan, 1969 [104] Genus: Cardites Link, 1807 [105] Cardites antiquatus (Linnaeus, 1758) [69] Genus: Megacardita Sacco, 1899 [62] Megacardita striatissima (Cailliaud in Mayer, 1868) [106] Subfamily: Scalaricarditinae Pérez, 2019 [45] Genus: Coripia de Gregorio, 1885 [107] Coripia corbis (Philippi, 1836) [108] Genus: Scalaricardita Sacco, 1899 [62] Scalaricardita scalaris (J. de C. Sowerby, 1825) [109] Order: Lucinida Gray, 1854 [89] Superfamily: Lucinoidea J. Fleming, 1828 [110] Family: Lucinidae J. Fleming, 1828 [110] Subfamily: Lucininae J. Fleming, 1828 [110] Genus: Megaxinus Brugnone, 1880 [111] Megaxinus transversus (Bronn, 1831) [25] Order: Adapedonta Cossmann and Peyrot, 1909 [112] Superfamily: Solenoidea Lamarck, 1809 [82] Family: Pharidae H. Adams and A. Adams, 1856 [77] Subfamily: Cultellinae Davies, 1935 [113] Genus: Ensis Schumacher, 1817 [114] Ensis cf. siliqua (Linnaeus, 1758) [69] Order: Cardiida Férussac, 1822 [87] Superfamily: Cardioidea Lamarck, 1809 [82] Family: Cardiidae Lamarck, 1809 [82] Subfamily: Orthocardiinae Schneider, 2002 [115] Genus: Europicardium Popov, 1977 [116] Europicardium multicostatum (Brocchi, 1814) [46] Superfamily: Tellinoidea Blainville, 1814 [117] Family: Tellinidae Blainville, 1814 [117] Subfamily: Arcopagiinae Huber, Langleit and Kreipl in Huber, 2015 [44] Genus: Arcopagia T. Brown, 1827 [118] Arcopagia crassa (Pennant, 1777) [119] Family: Psammobiidae J. Fleming, 1828 [110] Genus: Gari Schumacher, 1817 [114] Gari depressa (Pennant, 1777) [119] Gari tellinella (Lamarck, 1818) [120] Order: Venerida Gray, 1854 [89] Superfamily: Mactroidea Lamarck, 1809 [82] Family: Mactridae Lamarck, 1809 [82] Subfamily: Mactrinae Lamarck, 1809 [82] Genus: Mactra Linnaeus, 1767 [121] Mactra stultorum (Linnaeus, 1758) [69] Superfamily: Ungulinoidea Gray, 1854 [122] Family: Ungulinidae Gray, 1854 [122] Genus: Diplodonta Bronn, 1831 [25] Diplodonta rotundata (Montagu, 1803) [123] Superfamily: Veneroidea Rafinesque, 1815 [88] Family: Veneridae Rafinesque, 1815 [88] Genus: Callista Poli, 1791 [103] Callista chione (Linnaeus, 1758) [69] Genus: Chamelea Mörch, 1853 [124] Chamelea gallina (Linnaeus, 1758) [69] Genus: Clausinella Gray, 1851 [125] Clausinella fasciata (da Costa, 1778) [86] Genus: Gouldia C.B. Adams, 1847 [126] Gouldia minima (Montagu, 1803) [123] Genus: Timoclea T. Brown, 1827 [118] Timoclea ovata (Pennant, 1777) [119] Genus: Venus Linnaeus, 1758 [69] Venus casina Linnaeus, 1758 [69] Order: Myida Stoliczka, 1870 [81] Superfamily: Myoidea Lamarck, 1809 [82] Family: Corbulidae Lamarck, 1818 [120] Genus: Corbula Bruguière, 1797 [127] Corbula revoluta (Brocchi, 1814) [46] Genus: Varicorbula Grant and Gale, 1931 [128] Varicorbula gibba (Olivi, 1792) [129] |

5. Discussion

5.1. Diversity and Comparison with Other Correlative Assemblages of the WPM

5.2. Taphonomic Imprint of the Bivalve Assemblages

5.3. Palaeobiology and Depositional Setting

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Choffat, P. Observations sur le Pliocéne du Portugal. Bull. Soc. Belg. Géol. Paléontol. d’Hydrol. 1889, 3, 119–123. [Google Scholar]

- Dollfus, G.F.; Cotter, J.C.B. Mollusques tertiaires du Portugal. Le Pliocène au Nord du Tage (Plaisancian). Pelecypoda. Mem. Com. Serv. Geol. Port 1909, 40, 1–103. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, L.R. Pliocene Mollusca from Portugal. Mem. E Not. 1936, 9, 47–75. [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira, C.; Zbyszewski, G. Note sur le Pliocène de la Région à l’Ouest de Pombal. Comun. Dos Serv. Geol. Port. 1951, 32, 295–302. [Google Scholar]

- Diniz, F.; Silva, C.M.; Cachão, M. O Pliocénico de Pombal (Bacia do Mondego, Portugal Oeste): Biostratigrafia, Paleoecologia e Paleobiogeografia. Est. Quatern. 2016, 14, 41–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.M. Gastrópodes pliocénicos marinhos de Vale de Freixo (Pombal, Portugal). Sistemática, Tafonomia, Paleoecologia. MSc Dissertation, Faculdade de Ciências da Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, C.M. Gastrópodes Pliocénicos Marinhos de Portugal. Sistemática, Paleoecologia, Paleobiologia, Paleobiogeografia. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, C.M.; Landau, B.M.; Domènech, R.; Martinell, J. Pliocene Atlanto-Mediterranean biogeography of Patella pellucida (Gastropoda, Patellidae): Palaeoceanographic implications. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2006, 233, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.M.; Landau, B.M.; Domènech, R.; Martinell, J. Pliocene Atlantic Molluscan Assemblages from the Mondego Basin (Portugal): Age and Palaeoceanographic implications. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2010, 285, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.M.; Landau, B.M.; La Perna, R. Biogeography of Iberian Atlantic Neogene marginelliform gastropods (Marginellidae, Cystiscidae): Global change and transatlantic colonization. J. Paleontol. 2011, 85, 1052–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landau, B.M.; Silva, C.M. The genus Sveltia (Gastropoda, Cancellariidae) in the Atlantic Pliocene of Iberia with a new species from the Cenozoic Mondego Basin of Portugal. J. Paleontol. 2022, 96, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landau, B.M.; Bakker, P.A.J.; Silva, C.M. The Inella group (Gastropoda: Triphoridae, Triphorinae) in the south-western Iberian Pliocene: First records with two new species. Basteria 2023, 87, 116–126. [Google Scholar]

- Pimentel, R. Bivalvia (Mollusca) do Pliocénico de Vale de Freixo (Pombal). MSc Thesis, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Almada, Portugal, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pimentel, R.; Callapez, P.; Legoinha, P. Lista taxonómica preliminar dos moluscos bivalves do Pliocénico marinho da jazida de Vale de Freixo (Pombal, Portugal). In Atas do IX Simpósio da Margem Ibérica Atlântica; Cunha, P.P., Dias, J., Veríssimo, H., Duarte, L.V., Dinis, P., Lopes, F.C., Bessa, A.F., Carmo, J.A., Eds.; Departamento de Ciências da Terra da Universidade de Coimbra: Coimbra, Portugal, 2018; pp. 225–226. ISBN 978-989-98914-2-5. [Google Scholar]

- Pimentel, R.; Callapez, P.; Legoinha, P. First occurrence of Cardilia michelottii Deshayes, 1844 (Bivalvia, Cardiliidae) in the Iberian Pliocene. Boletín Real Soc. Esp. Hist. Nat. 2019, 113, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, J.R.; Callapez, P.M.; Legoinha, P. Pliocene marine Bivalvia of Vale do Freixo (Pombal, Portugal): Updated taxonomic list and discusión. Geol. Acta 2021, 19, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Angelo, B.; Silva, C.M. Polyplacophora from the Pliocene of Vale de Freixo: Central-west Portugal. Boll. Malacol. 2003, 39, 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Dell’Angelo, B.; Landau, B.M.; Silva, C.M.; Sosso, M. Biogeography of northeastern Atlantic Neogene chitons (Mollusca, Polyplacophora): New data from the Pliocene of Portugal. J. Paleontol. 2022, 96, 814–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, P. Echinoidea from the Neogene of Portugal mainland. Palaeontos 2010, 18, 1–154. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, F.; Pereira, S.; Silva, C.M. Balanídeos do Pliocénico de Vale de Freixo (Pombal, Portugal): Dados preliminares. In Abstracts IX Congresso Jovens Investigadores em Geociências, LEG 2019, Évora, Portugal, 23–24 November 2019; Silva, V., Batista, A., Silva, M., Eds.; Centro Ciência Viva de Estremoz: Estremoz, Portugal, 2019; pp. 67–70. [Google Scholar]

- Nolf, D.; Silva, C.M. Otolithes de Poissons Pliocènes (Plaisancien) de Vale de Freixo, Portugal. Rev. Micropaleontol. 1997, 40, 273–282. [Google Scholar]

- Vieira, M.; Sousa, L.; Pais, J.; Pereira, D. Estudo Palinológico do Pliocénico de Vale do Freixo. In Livro de Resumos do VII Congresso Nacional de Geologia, Estremoz, Portugal, 29 June to 4 July 2006; Sociedade Geológica de Portugal: Évora, Portugal, 2006; pp. 673–676. [Google Scholar]

- Cachão, M. Posicionamento Biostratigráfico da Jazida Pliocénica de Carnide (Pombal). Gaia 1990, 2, 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- Okada, H.; Bukry, D. Supplementary modification and introduction of code numbers to the low-latitude coccolith biostratigraphic zonation. Mar. Micropaleontol. 1980, 5, 321–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronn, H.G. Italiens Tertiär-Gebilde und Deren Organische Einschlusse; Karl Groos: Heidelberg, Germany, 1831. [Google Scholar]

- Rocha, A.T.; Ferreira, J.M. Estudo dos foraminíferos fósseis do pliocénico da região de Pombal. Rev. Fac. Ciênc. Lisb. 2ª Série-C 1953, 3, 129–156. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, G.S.; Colom, G. Contribuição para o estudo da micropaleontologia dos depósitos detríticos pliocénicos de Portugal. Memórias E Notícias 1954, 37, 37–60. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, J.M. Ocorrência das famílias Lagenidae e Globigerinidae no Pliocénico de Pombal. In Comunicações do XXV Congresso Luso-Espanhol para o Progresso das Ciências; Sevilha, Spain, 23–26 November 1960; Associação Portuguesa para o Progresso das Ciências: Lisboa, Portugal, 1960; p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso, J.L. O Pliocénico marinho de Caldas da Rainha e de Pombal. Sedimentologia e Micropaleontologia. Enquadramento Paleogeográfico e Paleoecológico. In Volume d’hommage au Géologue Georges Zbyszewski; Recherche sur les Civilisations: Paris, France, 1984; pp. 155–201. ISBN 2 86538-116-1. [Google Scholar]

- Pai, M. Quantitative Analysis of Foraminifera and Sedimentology of the Marine Pliocene of Vale Farpado (Pombal, West Portugal) and its Palaeoenvironmental Interpretation. MSc Thesis, University Nova de Lisboa, Almada, Portugal, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Callapez, P.M.; Danielsen, R.; Castilho, A. Occurrences of the amphi-Atlantic brown mussel Perna perna (Linné, 1758) (Mollusca, Bivalvia) in South Portugal since the Atlantic “climatic optimum”. Est. Quatern. 2012, 8, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cachão, M. Contribuição para o Estudo do Pliocénico Marinho Português. MSc Dissertation, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Pais, J.; Cunha, P.P.; Legoinha, P. Litostratigrafia do Cenozóico de Portugal. In Ciências Geológicas: Ensino e Investigação—Geologia Clássica; Neiva, J.M.C., Ribeiro, A., Victor, L.M., Noronha, F., Ramalho, M., Eds.; Associação Portuguesa de Geólogos e Sociedade Geológica de Portugal: Lisboa, Portugal, 2010; Volume 1, pp. 365–376. ISBN 978-989-96669-0-0. [Google Scholar]

- Pais, J.; Cunha, P.P.; Pereira, D.; Legoinha, P.; Dias, R.; Moura, D.; da Silveira, A.B.; Kullberg, J.C.; González-Delgado, J.A. The Paleogene and Neogene of western Iberia (Portugal): A Cenozoic Record in the European Atlantic Domain; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manuppella, G.; Zbyszewski, G.; Veiga Ferreira, O. Carta Geológica de Portugal na Escala de 1:50 000. Notícia Explicativa da Folha 23-A, Pombal; Serviços Geológicos de Portugal: Lisboa, Portugal, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Martini, E. Standard Tertiary and Quaternary calcareous nannoplankton zonation. In Proceedings of the 2nd Planktonic Conference, Rome, Italy, 23–28 September 1970; Farinacci, A., Ed.; Tecnoscienza: Rome, Italy, 1971; Volume 2, pp. 739–785. [Google Scholar]

- Bolli, H.M. Planktonic foraminifera from the Oligocene-Miocene Cipero and Lengua formations of Trinidad, BWI. Bull. U.S. Natl. Mus. 1957, 215, 97–131. [Google Scholar]

- Salvatorini, G. Alcune nuove specie di foraminiferi del Miocene Superiore della Toscana Marittima. Atti Soc. Tosc. Sci. Nat. Mem. Serie A 1967, 73, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Kennett, J.P.; Srinivasan, M.S. Neogene Planktonic Foraminifera: A Phylogenetic Atlas; Hutchinson Ross: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 1983; ISBN 978-0879330705. [Google Scholar]

- Spezzaferri, S.; Coxall, H.K.; Olsson, R.K.; Hemleben, C.H. Taxonomy, biostratigraphy, and phylogeny of Oligocene Globigerina, Globigerinella, and Quiltyella n. gen. In Atlas of Oligocene Planktonic Foraminifera; Wade, B.S., Olsson, R.K., Pearson, P.N., Huber, B.T., Berggren, W.A., Eds.; Cushman Foundation for Foraminiferal Research: Lawrence, KS, USA, 2018; Volume 46, pp. 179–214. [Google Scholar]

- Bieler, R.; Carter, J.G.; Coan, E.V. Classification of Bivalve Families. Malacologia 2010, 52, 113–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieler, R.; Mikkelsen, P.M.; Collins, T.M.; Glover, E.A.; González, V.L.; Graff, D.L.; Harper, E.M.; Healy, J.; Kawauchi, G.Y.; Sharma, P.P.; et al. Investigating the Bivalve Tree of Life—an exemplar-based approach combining molecular and novel morphological characters. Invertebr. Syst. 2014, 28, 32–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, J.G.; Altaba, C.R.; Anderson, L.C.; Araujo, R.; Biakov, A.S.; Bogan, A.E.; Campbell, D.C.; Campbell, M.; Chen, J.H.; Cope, J.C.W.; et al. A synoptical classification of the Bivalvia (Mollusca). Paleontol. Contrib. 2011, 4, 1–47. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, M. Compendium of Bivalves 2: A full-color guide to the remaining seven families. In A Systematic Listing of 8,500 Bivalve Species and 10,500 Synonyms; ConchBooks: Hackenheim, Germany, 2015; ISBN 978-3939767633. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez, D.E. Phylogenetic relationships of the family Carditidae (Bivalvia: Archiheterodonta). J. Syst. Palaeontol. 2019, 17, 1359–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brocchi, G. Conchiologia Fossile Subapennina, con Osservazioni Geologiche Sugli Apennini e sul Suolo Adiacente; Dalla Stamperia Reale: Milano, Italy, 1814; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Chirli, C. Malacofauna Pliocenica Toscana. Bivalvia: Pteriomorphia Beurlen, 1894; Privately published: Firenze, Italy, 2014; Volume 10. [Google Scholar]

- Chirli, C. Malacofauna Pliocenica Toscana. Bivalvia: Heteroconchia Hertwig, 1895; Privately published: Firenze, Italy, 2015; Volume 11. [Google Scholar]

- Chirli, C. Malacofauna Pliocenica Toscana. Bivalvia: Heteroconchia Hertwig, 1895—Protobranchia Pelsener, 1889; Privately published: Firenze, Italy, 2016; Volume 12. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, A. Phylogenetics of British saddle oysters (bivalvia: Anomiidae)—A review of the shell morphology, internal anatomy and genetics of Pododesmus in British waters. J. Conchol. 2017, 42, 317–325. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, M. Compendium of Bivalves. In A Full-Color Guide to 3300 of the World’s Marine Bivalves. A Status on Bivalvia After 250 Years of Research; ConchBooks: Hackenheim, Germany, 2010; ISBN 978-3939767282. [Google Scholar]

- La Perna, R. Revision on the Nuculanidae (Bivalvia: Protobranchia) from the Cerulli Irelli collection (Mediterranean, Pleistocene). Palaeontogr. Ital. 2007, 91, 109–140. [Google Scholar]

- La Perna, R. A revision of the genus Europicardium Popov, 1977 (Bivalvia: Cardiidae) from the European Neogene: Tracking palaeogeography and climate changes. J. Syst. Palaeontol. 2017, 15, 287–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauriat-Rage, A. Les Bivalves du Redonien (Pliocène atlantique de France). Signification stratigraphique et paléobiogéographique. Mém. Mus. Natl. D’histoire Nat. Sci. Terre 1981, 45, 1–173. [Google Scholar]

- Lauriat-Rage, A. Les Astartidae (Bivalvia) du Redonien (Pliocène atlantique de France). Systématique, Biostratigraphie, Biogéographie. Mém. Mus. Natl. D’histoire Nat. Sci. Terre 1982, 48, 1–118. [Google Scholar]

- Lauriat-Rage, A. Les Bivalves du Pliocene de Normandie. Bull. Mus. Natl. Hist. Nat. 1986, 1, 3–51. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano-Francisco, M.C. Los bivalvos del Plioceno de la Provincia de Málaga. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Málaga, Málaga, Spain, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Sacco, F. I Molluschi del Terreni Terziarii del Piemonte e della Liguria; Carlo Clausen: Torino, Italy, 1897; Volume 23. [Google Scholar]

- Sacco, F. I Molluschi del Terreni Terziarii del Piemonte e della Liguria; Carlo Clausen: Torino, Italy, 1897; Volume 24. [Google Scholar]

- Sacco, F. I Molluschi del Terreni Terziarii del Piemonte e della Liguria; Carlo Clausen: Torino, Italy, 1898; Volume 25. [Google Scholar]

- Sacco, F. I Molluschi del Terreni Terziarii del Piemonte e della Liguria; Carlo Clausen: Torino, Italy, 1898; Volume 26. [Google Scholar]

- Sacco, F. I Molluschi del Terreni Terziarii del Piemonte e della Liguria; Carlo Clausen: Torino, Italy, 1899; Volume 27. [Google Scholar]

- Sacco, F. I Molluschi del Terreni Terziarii del Piemonte e della Liguria; Carlo Clausen: Torino, Italy, 1900; Volume 28. [Google Scholar]

- Sacco, F. I Molluschi del Terreni Terziarii del Piemonte e della Liguria; Carlo Clausen: Torino, Italy, 1901; Volume 29. [Google Scholar]

- Zbyszewski, G. Étude structurale de l’aire typhonique de Caldas da Rainha. Mem. Serv. Geol. Port. 1959, 3, 1–182. [Google Scholar]

- Zbyszewski, G.; Camarate França, J.; Veiga Ferreira, O.; Matos, M.; Carreira de Deus, P.; Oliveira, J.; Rodrigues, L.; Rodrigues, A.; Nery, F. Carta Geológica de Portugal na escala 1:50000. Notícia Explicativa da Folha 26-B, Alcobaça; Serviços Geológicos de Portugal: Lisboa, Portugal, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Zbyszewski, G.; Moitinho de Almeida, F. Carta Geológica de Portugal na escala 1:50 000. Notícia Explicativa da Folha 26-D, Caldas da Rainha; Serviços Geológicos de Portugal: Lisboa, Portugal, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, M.; Callapez, P.M.; Ferreira Soares, A. First record of Similipecten similis (Laskey, 1811) (Mollusca, Bivalvia, Pectinacea) in the Pliocene of Portugal. Portugala 2005, 5, 29–30. [Google Scholar]

- Linnaeus, C. Systema Naturae per Regna Tria Naturae, Secundum Classes, Ordines, Genera, Species, cum Characteribus, Differentiis, Synonymis, Locis, Editio Decima, Reformata; Laurentius Salvius: Stockholm, 1758. [Google Scholar]

- Pelseneer, P. Sur la classification phylogenetique de pelecypods. Bull. sci. Fr. Belg. 1889, 20, 27–52. [Google Scholar]

- Dall, W.H. On the hinge of pelecypods and its development, with an attempt toward a better subdivision of the group. Am. J. Sci. 1889, 3, 445–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, J.E. A Supplement to the Appendix of Captain Perry’s Voyage for the Discovery of a North West Passage in the Years 1819–1820, Containing an Account of the Subjects of Natural History; Appendix X. Natural history, shells; J. Murray: London, UK, 1824. [Google Scholar]

- Iredale, T. Australian molluscan notes. Nº I. Rec. Aust. Mus. 1931, 18, 201–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowerby, J. The Mineral Conchology of Great Britain; or, Coloured Figures and Descriptions of Those Remains of Testaceous Animals or Shells, Which Have Been Preserved at Various Times and Depths in the Earth; B. Arding and Merrett: London, UK, 1815–1818; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Lamarck, J.-B.M. Prodrome d’une nouvelle classification des coquilles, comprenant une rédaction appropriée des caractères génériques, et l’établissement d’un grand nombre de genres nouveaux. Mem. Soc. D’histoire Nat. Paris 1799, 1, 63–91. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Carter, J.G.; Campbell, D.C.; Campbell, M.R. Cladistic perspectives on early bivalve evolution. In The Evolutionary Biology of the Bivalvia. Geological Society Special Publication 177; Harper, E.M., Taylor, J.D., Crame, J.A., Eds.; The Geological Society: London, UK, 2000; pp. 47–79. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, H.; Adams, A. The Genera of Recent Mollusca Arranged According to Their Organisation; Van Voorst: London, UK, 1853–1858; Volume 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Risso, A. Histoire Naturelle des Principales Productions de l’Europe Méridionale et Principalement de Celles des Environs de Nice et des Alpes-Maritime; Mollusques, E.G., Ed.; Levrault: Paris, France, 1826; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Grobben, C. Zur Kenntniss der Morphologie, der Verwandtschafts verhältnisse und des Systems der Mollusken. Kais. Akad. Wiss. (Math.-Naturwissenschaftlichen Cl.) Sitzungsberichte 1894, 103, 61–86. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Beurlen, K. Beiträge zur Stammesgeschichte der Muscheln. Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Abteilung der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu München, Sitzungsberichte 1944, 1–2, 133–145. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Stoliczka, F. Cretaceous fauna of southern India. The Pelecypoda, with a review of all known genera of this class, fossil and recent. Mem. Geol. Soc. India (Palaeontol. Indica) 1870–1871, 3, 1–535. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Lamarck, J.B.M.d. Philosophie Zoologique, ou Exposition des Considérations Relative à l’Histoire Naturelle des Animaux; Chez Dentu et l’Auteur: Paris, France, 1809; Volume 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, R.B. Gabb’s California Cretaceous and Tertiary type lamellibranchs. Spec. Publ. Acad. Nat. Sci. Phila. 1930, 3, 1–314. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Conrad, T.A. Descriptions of new genera, subgenera and species of Tertiary and Recent shells. Proc. Acad. Nat. Sci. USA 1862, 14, 284–291. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Dall, W.H. Reports on the dredging operations off the west coast of Central America to the Galapagos, to the West coast of Mexico, and in the Gulf of California, in charge of Alexander Agassiz, carried on by the U.S. Fish Commission steamer “Albatross,” during 1891, Lieut. Commander Z.L. Tanner, U.S.N., commanding. XXXVII. Reports on the scientific results of the expedition to the eastern tropical Pacific, in charge of Alexander Agassiz, by the U.S. Fish Commission steamer “Albatross,” from October, 1904, to March, 1905, Lieut. commander L.M. Garrett, U.S.N., commanding. XIV. The Mollusca and the Brachiopoda. Bull. Mus. Comp. Zool. Harv. Coll. 1908, 43, 205–487. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- da Costa, E.M. Historia Naturalis Testaceorum Britanniae, or, The British Conchology. In Containing the Descriptions and Other Particulars of Natural History of the Shells of Great Britain and Ireland: Illustrated with Figures; Millan, White, Elmsley and Robson: London, UK, 1778. [Google Scholar]

- Férussac, A.E.J. Tableaux systématiques généraux de l’embranchement des mollusques, divisés en familles naturelles, suivis d’une table alphabétique générale et synonymique de toutes les dénominations génériques connues. In Tableaux Systématiques. Tableaux Systématiques des Animaux Mollusques. Classés en Familles Naturelles, dans Lesquels on a Etabli la Concordance de tous les Systèmes; Suivis d’un Prodrome Général Pour tous les Mollusques Terrestres ou Fluviatiles, Vivants ou Fossiles; Arthus-Bertrand: Paris, France, 1821–1822. [Google Scholar]

- Rafinesque, C.S. Analyse de la Nature ou Tableau de l’University et des Corps Organisés; Jean Barravecchia: Palermo, Italy, 1815. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, J.E. A revision of the genera of some of the families of conchifera or bivalve shells. Ann. Mag. Nat. Hist. Zool. Bot. Geol. 1854, 13, 408–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poli, J.X. Testacea Utriusque Siciliae Eorumque Historia et Anatome Tabulis Aeneis Illustrata; Regio Typographei: Parma, Italy, 1795; Volume 2, pp. 75–264. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, O.F. Zoologiae Danicae Prodromus, seu Animalium Daniae et Norvegiae Indigenarum Characteres, Nomina, et Synonyma Imprimis Popularium; Hallageri: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1776. [Google Scholar]

- Lamarck, J.B.M.d. Histoire Naturelle des Animaux sans Vertèbres; Author’s Edition: Paris, France, 1819; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- Eberzin, A.G. Molliuski—Pantsirnye, Dvustvorchatye, Lopatonogie. In Osnovy Paleontologii. Spravochnik Dlyapaleontologov i Geologov SSSR.; Orlov, Y.A., Ed.; Akademia Nauk: Moscow, Russia, 1960; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Bronn, H.G. Die Klassen und Ordnungen der Weichthiere (Malacozoa). In Wissenschaftlich Dargestellt in Wort und Bild, (Malacozoa Acephala); Winter: Leipzig and Heidelberg, Germany, 1862; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Iredale, T. Mollusca from the continental shelf of eastern Australia. Rec. Aust. Mus. 1929, 17, 157–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winckworth, R. Notes on the British species of Anomia. Proc. Malacol. Soc. Lond. 1922, 15, 32–34. [Google Scholar]

- Philippi, R.A. Pododesmus, ein neues Genus der Acephalen. Arch. Naturgesch. 1837, 3, 385–387. [Google Scholar]

- Gmelin, J.F. (Ed.) Caroli a Linnaei Systema Naturae per Regna Tria Naturae, 10th ed.; G.E. Beer: Leipzig, Germany, 1791; Volume 1, pp. 3021–3910. [Google Scholar]

- Hertwig, R. Lehrbuch der Zoologie, 3rd ed.; Gustav Fischer: Jena, Germany, 1895. [Google Scholar]

- d’Orbigny, A. Paléontologie Française, Terrains Crétacés. Lamellibranchia; Chez Arthus Bertrand: Paris, France, 1843–1848; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, S.V. A Monograph of the Crag Mollusca with Descriptions of Shells from the Upper Tertiaries of the British Isles. Bivalves; Palæontographical Society: London, UK, 1851–1857; Volume 2, Part 2. [Google Scholar]

- Hinsch, W. Leitende Molluskengruppen im Obermiocän und Unterpliocän des östlichen Nordseebeckens. Geol. Jahrb. 1952, 67, 143–194. [Google Scholar]

- Poli, J.X. Testacea Utriusque Siciliae Eorumque Historia et Anatome Tabulis Aeneis Illustrata; Regio Typographei: Parma, Italy, 1791; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Chavan, A. Superfamily Carditacea. In Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology. Mollusca 6, Bivalvia; Moore, R.C., Ed.; Geological Society of America and University of Kansas: Boulder, CO, USA; Lawrence, CA, USA, 1969; Part N; Volume 1–2, pp. 543–561. [Google Scholar]

- Link, D.H.F. Beschreibung der Naturalien-Sammlung der Universität zu Rostock; Adlers Erben: Rostock, Germany, 1807; Part 3; pp. 101–165. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, K. Description de Coquilles fossiles des terrains tertiaires supérieurs. J. Conchyl. 1868, 16, 187–190. [Google Scholar]

- de Gregorio, A. Studi su talune conchiglie mediterranee viventi e fossili con una rivista del genere Vulsella. Bull. Della Soc. Malacol. Ital. 1885, 10, 129–288. [Google Scholar]

- Philippi, R.A. Enumeratio Molluscorum Siciliae cum Viventium tum in Tellure Tertiaria Fossilium, Quae in Itinere suo Observavit; Schropp: Berlin, Germany, 1836; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Sowerby, J. de C. The Mineral Conchology of Great Britain: Or, Coloured Figures and Descriptions of Those Remains of Testaceous Animals or Shells, Which Have Been Preserved at Various Times and Depths in the Earth; R. Taylor: London, UK, 1825; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming, J. A History of British Animals, Exhibiting the Descriptive Characters and Systematical Arrangement of the Genera and Species of Quadrupeds, Birds, Reptiles, Fishes, Mollusca, and Radiata of the United Kingdom; including the Indigenous, Extirpated, and Extinct Kinds, Together with Periodical and Occasional Visitants; Bell and Bradfute: Edinburgh, Scotland; James Duncan: London, UK, 1828. [Google Scholar]

- Brugnone, G. Le conchiglie plioceniche selle vicinaze di Caltanisetta. Bolletino Soc. Malacol. Ital. 1880, 6, 85–158. [Google Scholar]

- Cossmann, M.; Peyrot, A. Conchologie Néogénique de l’Aquitaine. Pélécypodes; A. Saugnac: Bordeaux, France, 1909; Volume 1, Part 1. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, A.M. Tertiary Faunas. A Textbook for Oilfield Palaeontologists and Students of Geology. In The Composition of Tertiary Faunas; Thomas Murby and Co.: London, UK, 1935; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher, C.F. Essai d’un Nouveau Système des Habitations des Vers Testacés avec XXII Planches; L’Imprimerie de Ma. le directeur Schultz: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1817. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, J.A. Phylogeny of cardiid bivalves (cockles and giant clams): Revision of the Cardiinae and the importance of fossils in explaining disjunct biogeographical distributions. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 2002, 136, 321–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, S.V. Mikrostruktura rakoviny i sistematika kardiid. Tr. Paleontol. Inst. Akad. Nauk SSSR 1977, 153, 1–124. [Google Scholar]

- Blainville, H.-M.D.d. Mémoire sur la classification méthodique des animaux mollusques, et établissement d’une nouvelle considération pour y parvenir. Bull. Sci. Par Soc. Philomatique Paris Zool. 1814, 1814, 175–180. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T. Illustrations of the Conchology of Great Britain and Ireland. Drawn from Nature; Lizars, W.H., Lizars, D., Highley, S., Eds.; Wentworth Press: Edinburgh/London, UK, 1827. [Google Scholar]

- Pennant, T. British Zoology: Crustacea. Mollusca. Testacea; William Eyres: London, UK, 1777; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Lamarck, J.B.M.d. Histoire Naturelle des Animaux sans Vertèbres; Deterville/Verdière: Paris, France, 1818; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Linnaeus, C. Systema Naturae per Regna tria Naturae, Secundum Classes, Ordines, GENERA, species, cum Characteribus, Differentiis, Synonymis, Locis, Editio Duodécima; Laurentius Salvius: Stockholm, Sweden, 1767; pp. 533–1327. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, J.E. Additions and corrections to the arrangement of the families of bivalve shells. Ann. Mag. Nat. Hist. Zool. Bot. Geol. 1854, 14, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montagu, G. Testacea Britannica or Natural History of British Shells, Marine, Land, and Fresh-Water, Including the Most Minute: Systematically Arranged and Embellished with Figures; J. White: London, UK, 1803; Volume 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Mörch, O.A.L. Catalogus Conchyliorum quae Reliquit D. Alphonso d’Aguirra and Gadea Comes de Yoldi. Acephala, Annulata, Cirripedia, Echinodermata; L. Klein: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1853; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, J.E. List of the Specimens of British Animals in the Collection of the British Museum. Mollusca Acephala and Brachiopoda; Taylor: London, UK, 1851; Part 7. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, C.B. Catalogue of the Genera and Species of Recent Shells in the Collection of C.B. Adams; Justus Cobb: Middlebury, VT, USA, 1847. [Google Scholar]

- Bruguière, J.G. Tableau encyclopédique et méthodique des trois règnes de la nature. In Vers, Coquilles, Mollusques et Polypiers; H. Agasse: Paris, France, 1797; Part 19; pp. 190–286. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, U.S.; Gale, H.R. Catalogue of the marine Pliocene and Pleistocene Mollusca of California and adjacent region. Mem. San Diego Soc. Nat. Hist. 1931, 1, 1–1036. [Google Scholar]

- Olivi, G. Zoologia Adriatica, Ossia Catalogo Ragionato Degli Animali del Golfo e Della Lagune di Venezia; G. Remondini e fl.: Bassano, Italy, 1792. [Google Scholar]

- Philippi, R.A. Enumeratio Molluscorum Siciliae cum Viventium tum in Tellure Tertiaria Fossilium, quae in Itinere suo Observavit; Eduard Anton: Halle, Germany, 1844; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Lamarck, J.B.M.d. Suite des Mémoires sur les fossiles des arredores de Paris. Ann. Mus. Hist. Nat. Paris 1805, 6, 214–221. [Google Scholar]

- Cocconi, G. Enumerazione sistematica dei molluschi miocenici e pliocenici di Parma e Piacenza. Mem. Dell’ Accad. Delle Sci. Dell’istituto Bologna 1873, 3, 1–372. [Google Scholar]

- Laskey, J. Account of North British Testacea. Mem. Wernerian Nat. Hist. Soc. 1811, 1, 370–414. [Google Scholar]

- Sowerby I, G.B. The Genera of Recent and Fossil Shells, for the Use of Students, in Conchology and Geology; Privately published: London, UK, 1821–1825; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Goldfuss, G.A. Petrefacta Germaniae tam ea, quae in Museo Universitatis Regiae Borussicae Fridericiae Wilhelmiae Rhenanae Servantur quam alia Quaecunque in Museis Hoeninghusiano, Muensteriano Aliisque Extant, Iconibus et Descriptionibus Illustrata; Arnz & Comp.: Düsseldorf, Germany, 1833–1841; Part 2. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, K. Découverte des couches à Congéries dans le bassin du Rhône. Vierteljahresschr. Naturforschenden Ges. Zür. 1871, 16, 185–203. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, O.G. Osservazioni Zoologiche Intorno ai Testacei dell’Isola di Pantelleria; Tipografia della Minerva: Napoli, Italy, 1829. [Google Scholar]

- Born, I. Index Rerum Naturalium Musei Caesarei Vindobonensis. Verzeichniss der Natürlichen Seltenheiten des K.K. Naturalien Kabinets zu Wien. Schalthiere; Officina Krausiana: Vienna, Austria, 1778; Part 1. [Google Scholar]

- Sowerby, G.B., II. The Conchological Illustrations; or Coloured Figures of Hitherto Unfigured Recent Shells; Privately published: London, UK, 1834–1840. [Google Scholar]

- Bucquoy, E.; Dautzenberg, P.h.; Dollfus, G. Les Mollusques marins du Roussillon. Pèlècypodes; J.-B. Baillière & Fils: Paris, France, 1887–1898; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Sowerby, J. The Mineral Conchology of Great Britain; or Coloured Figures and Descriptions of Those Remains of Testaceous Animals or Shells, Which Have Been Preserved at Various Times and Depths in the Earth; Privately Published: London, UK, 1826–1835; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, W. Observations on the hinges of British Bivalve shells. Trans. Linn. Soc. Lond. 1802, 6, 154–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montagu, G. Supplement to Testacea Britannica with Additional Plates; Woolmer: Exeter, UK, 1808. [Google Scholar]

- Helbling, G.S. Beyträge zur Kenntniß neuer und seltener Konchylien. Aus einigen Wienerischen Sammlungen. Abh. Einer Priv. Böhmen Zur Aufn. Der Math. Der Vaterländischen Gesch. Und Der Naturgeschichte 1779, 4, 102–131. [Google Scholar]

- Deshayes, G.P.; Cardilia, G. Magasin de Zoologie, d’Anatomie Comparée et de Paléontologie; Typer Publishing House Inc.: Châteauguay, QC, Canada, 1844; Volume 6, pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Dillwyn, L.W. A Descriptive Catalogue of Recent Shells, Arranged According to the Linnean Method; with Particular Attention to the Synonymy; John and Arthur Arch: London, UK, 1817; Volume 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Retzius, A.J. Venus lithophaga descripta. Mem. Acad. Sci. Turin. 1788, 3, 11–14, Mémoires des Correspondans. [Google Scholar]

- de Basterot, B. Description géologique du bassin tertiaire du sud-ouest de la France. Mem. Soc. D’histoire Nat. Paris 1825, 2, 1–100. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, P. Untitled description of Scintilla recondita. In Les Fonds de la mer. Étude internationale sur les Particularités Nouvelles des Regions Sous-Marines; de Folin, L., Périer, L., Eds.; Savy: Paris, France, 1872–1876; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, O.G. Catalogo Sistematico e Ragionato de’ Testacei Delle Due Sicilie; Tipografia della Minerva: Napoli, Italy, 1830. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, P. Description d’une nouvelle espèce de Kellia des mers d’Europe. J. Conchyl. 1867, 15, 194–195. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-López, S. Tafonomía y Fosilización. In Tratado de Paleontología; Meléndez, B., Ed.; Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas: Madrid, Spain, 1999; pp. 51–107. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-López, S. Temas de Tafonomía; Departamento Paleontología, Universidad Complutense de Madrid: Madrid, Spain, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Fürsich, F.T.; Aberhan, M. Significance of time-averaging for palaeo community analysis. Lethaia 1990, 23, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, S.M. Relation of shell form to life habits in the Bivalvia (Mollusca). Geol. Soc. Am. Mem. 1970, 125, 1–296. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, A. Bivalves Marinhos do Miocénio Superior (Tortoniano superior) de Cacela (Algarve, Portugal). MSc Dissertation, Unidade de Ciências e Tecnologias dos Recursos Aquáticos, Universidade do Algarve, Faro, Portugal, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley, S.M. Treatise Online no. 72: Part N, Revised, Volume 1, Chapter 19: Evolutionary Ecology of the Bivalvia. Treatise Online. [CrossRef]

- Kidwell, S.M.; Jablonski, D. Taphonomic feedback: Ecological consequences of shell accumulation. In Biotic Interactions in Recent and Fossil Benthic Communities; Tevesz, M.J.S., McCall, P.L., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 195–248. ISBN 978-1-4757-0742-7. [Google Scholar]

- Montfort, P.D. Conchyliologie Systématique et Classification Méthodique des Coquilles; Schoell: Paris, France, 1808; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Langer, M.R. Epiphytic foraminifera. Mar. Micropaleontol. 1993, 20, 235–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, J.W. Ecology and Applications of Benthic Foraminifera; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006; ISBN 978-0521070096. [Google Scholar]

- Bernasconi, E.; Cusminsky, G.; Gordillo, S. Distribution of foraminifera from South Shetland Islands (Antarctic): Ecology and taphonomy. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2019, 29, 100653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poppe, G.T.; Goto, Y. European seashells. Scaphopoda, Bivalvia, Cephalopoda; Verlag Christa Hemmen: Wiesbaden, Germany, 1993; Volume 2, ISBN 978-3925919114. [Google Scholar]

- Saldanha, L. Fauna submarina atlântica, 3rd ed.; Publicações Europa-América: Lisboa, Portugal, 1997; ISBN 978-9721038752. [Google Scholar]

- Serres, M.d. Géognosie des Terrains Tertiaires, ou Tableau des Principaux Animaux Invertébrés des Terrains Marins Tertiaires du Midi de la France; Pomathio-Durville: Paris, France, 1829. [Google Scholar]

- Defrance, J.L.M. Fissurella. In Dictionnaire des Sciences Naturelles, dans Lequel on Traite Méthodiquement des Différens êtres de la Nature, Considérés Soit en eux-mêmes, D’après l’état Actuel de nos Connoissances, Soit Relativement à L’utilité qu’en Peuvent Retirer la Médecine, L’agriculture, le Commerce et les Artes; Suivi d’une Biographie des Plus Célèbres Naturalistes; Cuvier, F., Ed.; F.G. Levrault/Le Normant: Strasbourg/Paris, France, 1820; Volume 17, pp. 76–79. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, G.; Jacob, E. Descriptions of Nautilus lobatulus. In Essays on the Microscope: Containing a Practical Description of the Most Improved Microscopes; a General History of Insects, Their Transformations, Peculiar Habits, and Œconomy: An Account of the Various Species, and Singular Properties, of the Hydræ and Vorticellæ: A Description of Three Hundred and Eighty-Three Animalcula: With a Concise Catalogue of Interesting Objects: A view of the Organization of Timber, and the Configuration of Salts, When Under the Microscope; Adams, A., Kanmacher, F., Eds.; Dillon and Keating: London, UK, 1798; p. 642. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Botí, M.; Foster, G.; Chalk, T.; Rohling, E.J.; Sexton, P.F.; Lunt, D.J.; Pancost, R.D.; Badger, M.P.S.; Schmidt, D.N. Plio-Pleistocene climate sensitivity evaluated using high-resolution CO2 records. Nature 2015, 518, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haywood, A.M.; Dowsett, H.J.; Dolan, A.M.; Rowley, D.; Abe-Ouchi, A.; Otto-Bliesner, B.; Chandler, M.A.; Hunter, S.J.; Lunt, D.J.; Pound, M.; et al. The Pliocene Model Intercomparison Project (PlioMIP) Phase 2: Scientific objectives and experimental design. Clim. Past 2012, 12, 663–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowsett, H.J.; Poore, R.Z. Pliocene sea surface temperatures of the North Atlantic Ocean at 3.0 Ma. Quat. Sci. Rev. 1991, 10, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowsett, H.J.; Chandler, M.A.; Cronin, T.M.; Dwyer, G.S. Middle Pliocene sea surface temperature variability. Paleoceanography 2005, 20, PA2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowsett, H.; Dolan, A.; Rowley, D.; Moucha, R.; Forte, A.M.; Mitrovica, J.X.; Pound, M.; Salzmann, U.; Robinson, M.; Chandler, M.; et al. The PRISM4 (mid-Piacenzian) paleoenvironmental reconstruction. Clim. Past 2016, 12, 1519–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naafs, B.D.A.; Voelker, A.H.L.; Karas, C.; Andersen, N.; Sierro, F.J. Repeated near-collapse of the Pliocene sea surface temperature gradient in the North Atlantic. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatology 2020, 35, e2020PA003905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monegatti, P.; Raffi, S. Mediterranean-Middle Eastern Atlantic Façade: Molluscan biogeography & ecobiostratigraphy throughout the Late Neogene. Açoreana Rev. Estud. Açoreanos 2007, 5, 126–139. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, C.M.; Landau, B.M. A idade da malacofauna pliocénica da Bacia do Mondego (Portugal) e suas implicações paleoceanográficas. Portugala 2009, 14, 43–46. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, J.W. Benthic foraminiferal assemblages: Criteria for the distinction of temperate and subtropical carbonate environments. In Micropaleontology of Carbonate Environments; Hart, M.B., Ed.; Halsted Press: New York, NY, USA, 1987; pp. 9–20. ISBN 9780470207628. [Google Scholar]

- Cachão, M. Utilização de nanofósseis calcários em biostratigrafia, paleoceanografia e paleoecologia. Aplicações ao Neogénico do Algarve (Portugal) e do Mediterrâneo Ocidental (ODP 653) e à problemática de Coccolithus pelagicus. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bartoli, G.; Hönisch, B.; Zeebe, R.E. Atmospheric CO2 decline during the Pliocene intensification of Northern Hemisphere glaciations. Paleoceanography 2011, 26, PA4213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondanaro, A.; Dominici, S.; Danise, S. Response of Mediterranean Sea bivalves to Pliocene–Pleistocene environmental changes. Palaeontology 2024, 62, e12696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crippa, G.; Azzarone, M.; Bottini, C.; Crespi, S.; Felletti, F.; Marini, M.; Petrizzo, M.R.; Scarponi, D.; Raffi, S.; Raineri, G. Bio- and lithostratigraphy of lower Pleistocene marine successions in western Emilia (Italy) and their implications for the first occurrence of Arctica islandica in the Mediterranean Sea. Quat. Res. 2019, 92, 549–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosel, R.v.; Gofas, S. Marine Bivalves of Tropical West Africa; Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle: Paris, France, 2019; ISBN 9782856538883. [Google Scholar]

- Seki, O.; Foster, G.L.; Schmidt, D.N.; Mackensen, A.; Kawamura, K.; Pancost, R.D. Alkenone and boron-based Pliocene pCO2 records. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2010, 292, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). Trends in Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide. Available online: https://www.esrl.noaa.gov/gmd/ccgg/trends/ (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- Saupe, E.E.; Hendricks, J.R.; Portell, R.W.; Dowsett, H.J.; Haywood, A.; Hunter, S.J.; Lieberman, B.S. Macroevolutionary consequences of profound climate change on niche evolution in marine molluscs over the past three million years. Proc. R. Soc. B 2014, 281, 20141995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Bivalve Species | VFa (This Work) | VFr | Ca * | Al MG L | CR Nz |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ennucula laevigata (J. Sowerby, 1818) [74] | X | X | |||

| Nucula nucleus (Linnaeus, 1758) [69] | X | X | X | X | |

| Lembulus pella (Linnaeus, 1758) [69] | X | X | X | X | |

| Saccella commutata (Philippi, 1844) [130] | X | ||||

| Total Protobranchia Species | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Bivalve Species | VFa (This Work) | VFr | Ca * | Al MG L | CR Nz |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mytilus galloprovincialis Lamarck, 1819 [92] | X | ||||

| Modiolus sp. | X | X | |||

| Gregariella sp. | X | ||||

| Barbatia mytiloides (Brocchi, 1814) [46] | X | X | X | ||

| Anadara diluvii (Lamarck, 1805) [131] | X | X | |||

| Anadara pectinata (Brocchi, 1814) [46] | X | X | X | ||

| Striarca lactea (Linnaeus, 1758) [69] | X | X | X | X | |

| Tetrarca tetragona Poli, 1795 [90] | X | X | X | ||

| Glycymeris glycymeris (Linnaeus, 1758) [69] | X | X | X | X | X |

| Glycymeris nummaria (Linnaeus, 1758) [69] | X | X | X | ||

| Ostrea edulis Linnaeus, 1758 [69] | X | X | X | X | X |

| Neopycnodonte cochlear (Poli, 1795) [90] | X | ||||

| Isognomon maxillatus (Lamarck, 1819) [92] | X | ||||

| Atrina fragilis (Pennant, 1777) [119] | X | X | X | ||

| Pteria hirundo (Linnaeus, 1758) [69] | X | X | |||

| Aequipecten opercularis (Linnaeus, 1758) [69] | X | X | X | ||

| Flexopecten flexuosus (Poli, 1795) [90] | X | X | X | ||

| Flexopecten inaequicostalis (Lamarck, 1819) [92] | X | ||||

| Manupecten pesfelis (Linnaeus, 1758) [69] | X | ||||

| Pecten benedictus Lamarck, 1819 [92] | X | X | X | X | X |

| Pecten jacobaeus (Linnaeus, 1758) [69] | X | ||||

| Perapecten scabrellus (Lamarck, 1819) [92] | X | ||||

| Lissochlamys excisa (Bronn, 1831) [25] | X | X | X | X | X |

| Hinnites crispus (Brocchi, 1814) [46] | X | X | |||

| Mimachlamys varia (Linnaeus, 1758) [69] | X | X | X | X | |

| Talochlamys ercolaniana (Cocconi, 1873) [132] | X | ||||

| Talochlamys multistriata (Poli, 1795) [90] | X | X | X | X | |

| Similipecten similis (Laskey, 1811) [133] | X | ||||

| Anomia ephippium Linnaeus, 1758 [69] | X | X | |||

| Heteranomia squamula (Linnaeus, 1758) [69] | X | X | |||

| Pododesmus squama (Gmelin, 1791) [98] | X | X | |||

| Lima lima (Linnaeus, 1758) [69] | X | X | |||

| Limaria loscombi (G. B. Sowerby I, 1823) [134] | X | ||||

| Limaria tuberculata (Olivi, 1792) [129] | X | X | X | ||

| Total Pteriomorphia Species | 9 | 26 | 13 | 11 | 24 |

| Bivalve Species | VFa (This Work) | VFr | Ca * | Al MG L | CR Nz |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laevastarte fusca (Poli, 1791) [103] | X | X | X | X | |

| Astarte af. concentrica Goldfuss, 1837 [135] | X | ||||

| Digitaria digitaria (Linnaeus, 1758) [69] | X | X | X | X | X |

| Goodallia triangularis (Montagu, 1803) [123] | X | ||||

| Cardita calyculata (Linnaeus, 1758) [69] | X | X | |||

| Cardites antiquatus (Linnaeus, 1758) [69] | X | X | X | ||

| Megacardita striatissima (Cailliaud in Mayer, 1868) [106] | X | X | X | X | X |

| Centrocardita aculeata (Poli, 1795) [90] | X | ||||

| Cardita (Venericardia) matheroni Mayer, 1871 [136] | X | ||||

| Coripia corbis (Philippi, 1836) [108] | X | X | |||

| Scalaricardita scalaris (J. de C. Sowerby, 1825) [109] | X | X | X | X | |

| Gastrochaena sp. | X | ||||

| Lucinoma borealis (Linnaeus, 1767) [121] | X | X | |||

| Lucinella divaricata (Linnaeus, 1758) [69] | X | X | |||

| Megaxinus transversus (Bronn, 1831) [25] | X | X | |||

| Loripinus fragilis (Philippi, 1836) [108] | X | ||||

| Ctena decussata (O. G. Costa, 1829) [137] | X | ||||

| Pharus legumen (Linnaeus, 1758) [69] | X | X | X | ||

| Phaxas pellucidus (Pennant, 1777) [119] | X | ||||

| Ensis siliqua (Linnaeus, 1758) [69] | X | X | X | X | X |

| Hiatella rugosa (Linnaeus, 1767) [121] | X | ||||

| Panopea glycimeris (Born, 1778) [138] | X | X | X | ||

| Procardium diluvianum (Lamarck, 1819) [92] | X | X | |||

| Acanthocardia aculeata (Linnaeus, 1758) [69] | X | X | X | ||

| Acanthocardia paucicostata (G. B. Sowerby II, 1834) [139] | X | ||||

| Papillicardium papillosum (Poli, 1791) [103] | X | X | |||

| Parvicardium scriptum (Bucquoy, Dautzenberg and Dollfus, 1892) [140] | X | ||||

| Laevicardium crassum (Gmelin, 1791) [98] | X | X | |||

| Europicardium multicostatum (Brocchi, 1814) [46] | X | X | X | ||

| Arcopagia corbis (Bronn, 1831) [25] | X | X | X | X | |

| Arcopagia crassa (Pennant, 1777) [119] | X | X | X | X | |

| Gastrana fragilis (Linnaeus, 1758) [69] | X | X | X | ||

| Gastrana laminosa (J. de C. Sowerby, 1827) [141] | X | ||||

| Macomopsis elliptica (Brocchi, 1814) [46] | X | X | X | ||

| Bosemprella incarnata (Linnaeus, 1758) [69] | X | ||||

| Oudardia compressa (Brocchi, 1814) [46] | X | ||||

| Peronidia albicans (Gmelin, 1791) [98] | X | X | |||

| Donax limai Dollfus and Cotter, 1909 [2] | X | ||||

| Donax rugosus Linnaeus, 1758 [69] | X | ||||

| Donax trunculus Linnaeus, 1758 [69] | X | ||||

| Donax variegatus (Gmelin, 1791) [98] | X | X | |||

| Donax venustus Poli, 1795 [90] | X | ||||

| Gari depressa (Pennant, 1777) [119] | X | X | X | ||

| Gari fervensis (Gmelin, 1791) [98] | X | X | |||

| Gari tellinella (Lamarck, 1818) [120] | X | X | |||

| Abra alba (W. Wood, 1802) [142] | X | X | |||

| Abra prismatica (Montagu, 1808) [143] | X | X | |||

| Chama gryphoides Linnaeus, 1758 [69] | X | X | |||

| Pseudochama gryphina (Lamarck, 1819) [92] | X | ||||

| Coralliophaga glabrata Brocchi, 1814 [46] | X | ||||

| Mactra stultorum (Linnaeus, 1758) [69] | X | X | X | X | |

| Spisula solida (Linnaeus, 1758) [69] | X | X | X | X | |

| Spisula subtruncata (da Costa, 1778) [86] | X | X | X | X | |

| Eastonia rugosa (Helbling, 1779) [144] | X | X | |||

| Lutraria lutraria (Linnaeus, 1758) [69] | X | X | X | ||

| Cardilia aff. michelottii Deshayes, 1844 [145] | X | ||||

| Diplodonta rotundata (Montagu, 1803) [123] | X | X | |||

| Callista chione (Linnaeus, 1758) [69] | X | X | X | X | X |

| Chamelea gallina (Linnaeus, 1758) [69] | X | X | X | ||

| Circomphalus foliaceolamellosus (Dillwyn, 1817) [146] | X | X | X | ||

| Clausinella fasciata (da Costa, 1778) [86] | X | X | X | X | X |

| Dosinia exoleta (Linnaeus, 1758) [69] | X | X | X | ||

| Dosinia lupinus (Linnaeus, 1758) [69] | X | X | |||

| Gouldia minima (Montagu, 1803) [123] | X | X | |||

| Petricola lithophaga (Retzius, 1788) [147] | X | ||||

| Pitar rudis (Poli, 1795) [90] | X | ||||

| Polititapes vetulus (Basterot, 1825) [148] | X | X | X | ||

| Timoclea ovata (Pennant, 1777) [119] | X | X | X | X | |

| Venus casina Linnaeus, 1758 [69] | X | X | X | ||

| Venus verrucosa Linnaeus, 1758 [69] | X | X | X | ||

| Sportella aff. recondita (P. Fischer, 1872) [149] | X | ||||

| Scacchia oblonga (Philippi, 1836) [108] | X | X | |||

| Bornia sebetia (O. G. Costa, 1830) [150] | X | ||||

| Pseudopythina macandrewi (P. Fischer, 1867) [151] | X | ||||

| Corbula revoluta (Brocchi, 1814) [46] | X | X | |||

| Varicorbula gibba (Olivi, 1792) [129] | X | X | X | ||

| Lentidium mediterraneum (O. G. Costa, 1830) [150] | X | ||||

| Sphenia anatina (Basterot, 1825) [148] | X | ||||

| Barnea parva (Pennant, 1777) [119] | X | ||||

| Pholadidea rugosa (Brocchi, 1814) [46] | X | X | |||

| Total Heteroconchia Species | 22 | 56 | 33 | 25 | 42 |

| Bivalve Species | Lifestyles | Feeding Strategies | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| En | Sen | Epb | Epc | Eps | D | S | |

| E. laevigata | X | X | |||||

| N. nucleus | X | X | |||||

| L. pella | X | X | |||||

| S. lactea | X | X | |||||

| G. glycymeris | X | X | |||||

| O. edulis | X | X | |||||

| F. flexuosus | X | X | |||||

| P. benedictus | X | X | |||||

| L. excisa | X | X | |||||

| T. multistriata | X | X | |||||

| H. squamula | X | X | |||||

| P. squama | X | X | |||||

| L. fusca | X | X | |||||

| D. digitaria | X | ||||||

| C. antiquatus | X | X | |||||

| M. striatissima | X | X | |||||

| C. corbis | X | ||||||

| S. scalaris | X | ||||||

| M. transversus | X | ||||||

| E. cf. siliqua | X | X | |||||

| E. multicostatum | X | X | |||||

| A. crassa | X | X | |||||

| G. depressa | X | ||||||

| G. tellinella | X | ||||||

| M. stultorum | X | X | |||||

| D. rotundata | X | ||||||

| C. chione | X | X | |||||

| C. gallina | X | ||||||

| C. fasciata | X | X | |||||

| G. minima | X | ||||||

| T. ovata | X | X | |||||

| V. casina | X | X | |||||

| C. revoluta | X | X | |||||

| V. gibba | X | X | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pimentel, R.J.; Callapez, P.M.; Pai, M.; Legoinha, P.; Dinis, P.A. Pliocene Marine Bivalvia from Vale Farpado (Pombal, Portugal): Palaeoenvironmental and Palaecological Significance. Geosciences 2025, 15, 309. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15080309

Pimentel RJ, Callapez PM, Pai M, Legoinha P, Dinis PA. Pliocene Marine Bivalvia from Vale Farpado (Pombal, Portugal): Palaeoenvironmental and Palaecological Significance. Geosciences. 2025; 15(8):309. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15080309

Chicago/Turabian StylePimentel, Ricardo J., Pedro M. Callapez, Mahima Pai, Paulo Legoinha, and Pedro A. Dinis. 2025. "Pliocene Marine Bivalvia from Vale Farpado (Pombal, Portugal): Palaeoenvironmental and Palaecological Significance" Geosciences 15, no. 8: 309. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15080309

APA StylePimentel, R. J., Callapez, P. M., Pai, M., Legoinha, P., & Dinis, P. A. (2025). Pliocene Marine Bivalvia from Vale Farpado (Pombal, Portugal): Palaeoenvironmental and Palaecological Significance. Geosciences, 15(8), 309. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15080309