1. Introduction

Imaging salt structures remains a major challenge in geophysical exploration, as conventional seismic methods often yield low-quality images in the presence of salt bodies. Salt domes—intrusive structures that pierce thick sedimentary sequences as they rise toward the surface (Belenitskaya [

1])—are particularly important in hydrocarbon exploration because they can form traps both beneath and along their flanks (Ratcliff et al. [

2]). The strong impedance contrasts between salt and surrounding sediments generate complex diffractions and illumination artifacts that hinder seismic imaging.

In contrast, the pronounced density contrasts between salt and country rocks produce distinctive gravity anomalies, making gravity and Full Tensor Gravity (FTG) surveys valuable tools for subsalt characterization [

3,

4,

5]. Conventional gravity surveys—such as Bouguer or Free-Air gravity—capture large-scale regional variations, whereas FTG gradiometry measures spatial derivatives of the gravitational field, emphasizing shorter wavelengths and improving depth control. Although gradiometric data are typically employed for depth estimation, when combined with gravity data, they also enhance the delineation of horizontal boundaries due to their directional sensitivity. This complementary behavior provides the motivation for the joint inversion approach presented in this study.

In addition to gravimetric data acquisition, gradiometric surveys are valuable because their inherently higher frequency content provides detailed information about shallow subsurface structures and is less affected by deeper or regional sources [

6,

7,

8]. Gradiometric and gravimetric data therefore offer complementary perspectives on the same geological features. While gradiometric surveys are particularly effective at delineating horizontal boundaries and capturing high-frequency anomalies, gravimetric data generally offer better depth constraints and are dominated by lower-wavenumber components.

Several studies have applied gravity and gradiometric data to characterize salt structures and other high-contrast geological bodies. Although these approaches have improved subsurface imaging, most treat FTG and scalar gravity data separately, limiting their ability to recover complex density contrasts. The complementary nature of these datasets—where gravity provides large-scale sensitivity and FTG resolves sharper gradients—motivates their simultaneous use.

The main scope of this study is to develop and validate a three-dimensional joint inversion framework that integrates FTG gradient and gravity observations to enhance the structural delineation of salt bodies. The proposed methodology combines a tensor–Euler-derived initial model, a wavenumber-enrichment scheme to balance spectral information, and a simulated annealing algorithm to optimize density distributions. Therefore, this work not only introduces techniques to better exploit gradiometric tensor measurements but also demonstrates their applicability through a real-data case study at the Vinton Dome, Louisiana.

To achieve a more accurate and stable initial model for inversion, this study incorporates several complementary techniques designed to enhance source localization and depth estimation. One such technique is the Euler Deconvolution method, which estimates the position and depth of anomalous bodies based on field gradients. Zhang et al. [

9] extended this approach into a tensor-based formulation known as Euler Tensor Deconvolution (ETD), which, when applied to both gravity and FTG datasets, improves the spatial definition of subsurface sources. We also integrate the methodology developed by Zapotitla-Roman [

10], Ortiz-Aleman et al. [

11] to refine depth estimates using gravimetric data. Furthermore, to strengthen the robustness of the initial model, we enrich the signal’s spectral content by combining the distinct frequency responses of gravity and gradiometry data. This fusion produces a third, spectrally balanced signal that enhances the resolution of density variations and improves subsequent inversion performance.

These techniques collectively support the construction of an initial three-dimensional density model that represents the most probable geometry and depth of the main anomalous bodies. This preliminary model is generated by combining the source positions estimated through Euler Tensor Deconvolution with the spectral information obtained from gravity and FTG data fusion. The resulting density distribution serves as the starting point for the inversion process, providing a physically consistent framework that constrains the search space and guides the optimization toward realistic subsurface configurations.

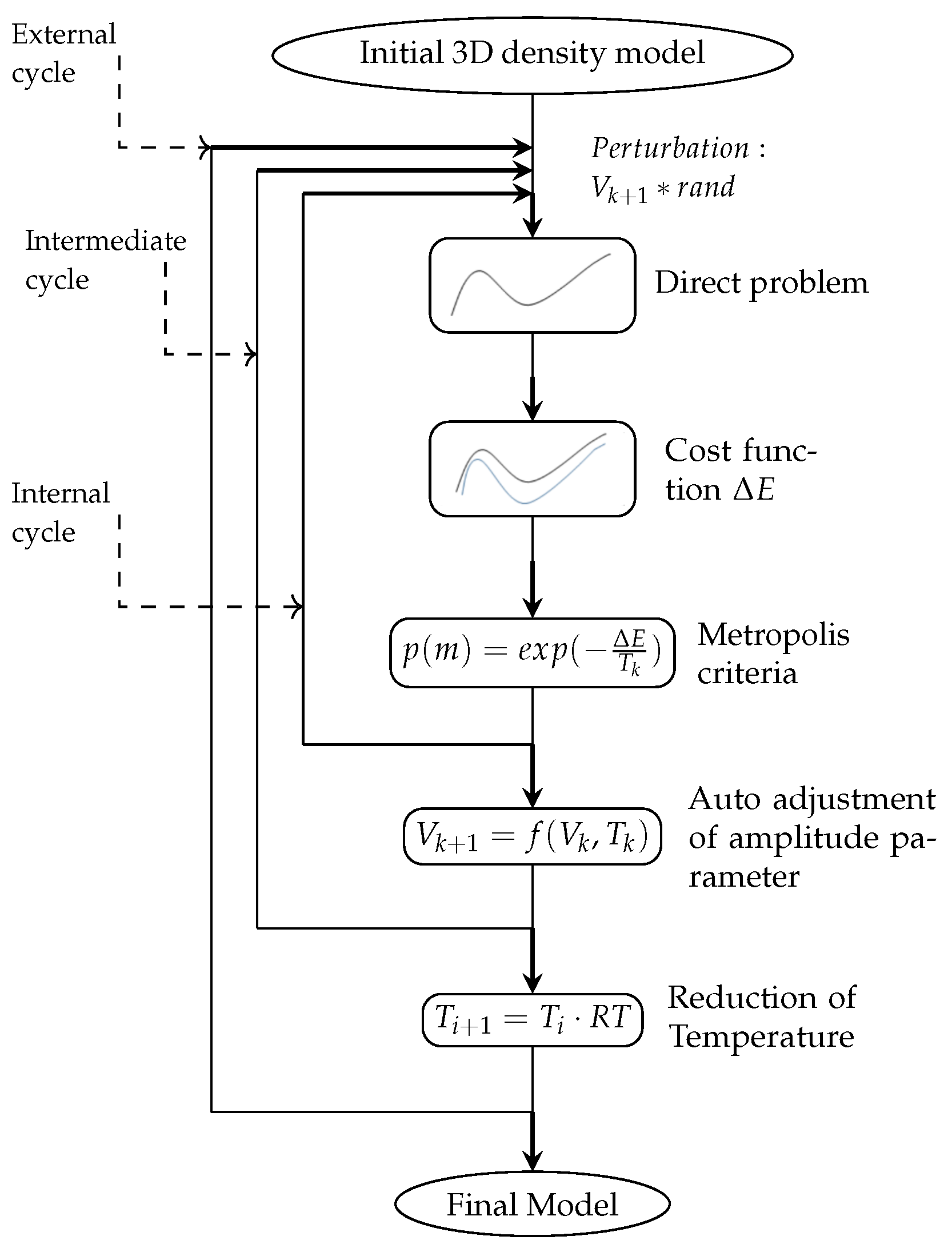

Simulated Annealing (SA) is employed as the global optimization algorithm to refine this initial model and minimize the misfit between observed and calculated gravity and FTG data. SA is particularly effective for this application because it can escape local minima and explore complex multidimensional parameter spaces, ensuring convergence toward a near-optimal density distribution. In our implementation, SA iteratively perturbs density values within the predefined model domain, accepting or rejecting updates based on the Boltzmann probability criterion. This process continues until the overall misfit and total energy function stabilize, producing a final model that best fits both datasets simultaneously [

12]. SA’s main drawback lies in its high computational demand; for this reason, it is sometimes replaced by faster linear inversion methods, which, however, may become trapped in local minima [

13,

14]. This heuristic method has been widely applied in various scientific domains, particularly in the inversion of geophysical data such as magnetic, electric, and gravity surveys [

11,

15,

16,

17,

18]. Because of its computational intensity, SA is often applied to problems involving relatively few parameters. Moreover, as the dimensionality of the solution space increases, it is common to optimize parameters sequentially—further increasing the method’s computational cost [

19].

One of the main objectives of this work is to leverage both the gradiometric tensor and the gravimetric vector datasets through the introduction of a cost function that simultaneously utilizes all available data, thereby generating a more realistic model that satisfies all nine real datasets rather than only one. Although this approach requires a substantial amount of information for each additional component, this challenge is addressed through the use of parallel programming to ensure feasible computing times. The generation of sensitivity matrices for the inversion, as well as the iterative computation of the forward problem, were optimized using OpenMP 5.0 directives.

The structure of this paper is as follows:

Section 2 presents the theoretical framework, beginning with the fundamentals of potential-field theory and the formulation of the gravity and gradiometry equations (

Section 2.1), followed by the description of the Simulated Annealing (SA) algorithm and its application to the inverse problem (

Section 2.2).

Section 3 contains the results.

Section 3.1 outlines the geological and geophysical context of the Vinton Dome.

Section 3.2 describes the gravimetric and gradiometric datasets and preprocessing procedures, including the residual of the vertical gravity component (

Section 3.2.1), the reconstruction of the horizontal components (

Section 3.2.2), and the wavenumber enrichment process (

Section 3.2.3).

Section 3.3 details the generation of the initial model using Euler Tensor Deconvolution.

Section 3.4 presents the inverse problem based on synthetic and real FTG data.

Section 3.5 presents the first inversion model, and

Section 3.6 presents the second and final inversion model and its geological interpretation. Finally,

Section 4 provides the discussion and concluding remarks, followed by practical recommendations and a summary of methodological limitations.

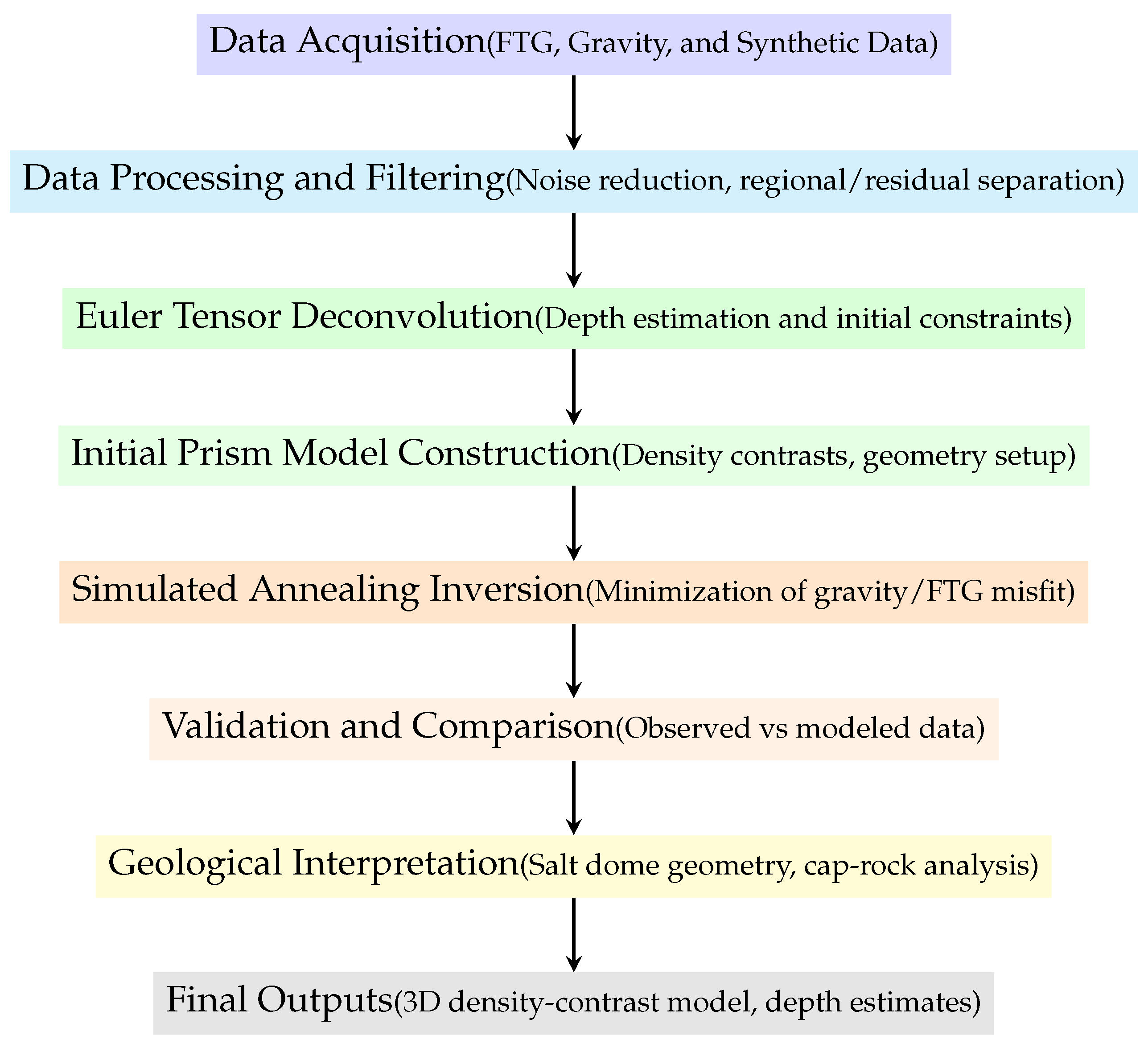

To summarize the methodological sequence developed in this study,

Figure 1 presents a schematic workflow of the entire gravity–FTG modeling and inversion process. The procedure begins with the acquisition and preprocessing of the measured FTG and gravity datasets, including noise reduction, Free-Air and terrain corrections, and regional–residual separation. Subsequently, Euler Tensor Deconvolution (ETD) is applied to obtain preliminary source positions and depth estimates, which serve as constraints for constructing the initial prism-based density model. This model is then refined through a simulated annealing inversion that jointly minimizes the misfit between the observed and modeled gravity and FTG fields. The final steps involve validating the inversion results and interpreting the 3D density-contrast model in terms of the geological structure of the Vinton Dome.

3. Results

In this study, two categories of gravity data were used: measured and synthetic. The measured dataset corresponds to the FTG survey acquired by Bell Geospace over the Vinton Dome in southwestern Louisiana, USA. This dataset includes the gravity field (

) and the six independent components of the gravity gradient tensor (

), recorded in milligals (mGal) and Eotvös, respectively. The synthetic data were generated through forward modeling using the prism-based configuration described in

Section 4 to assess the inversion performance.

The gravity field used in this study represents the observed gravity anomaly, which includes both Free-Air and terrain corrections and is therefore equivalent to a Bouguer-type anomaly. The gradiometric quantities correspond to the measured FTG gradients obtained from the same airborne survey. All quantities are consistently expressed in mGal for gravity components and in Eotvös for tensor gradients throughout the manuscript.

3.1. Vinton Dome Geological Setup

The Vinton Dome is a classic piercement-type salt structure located in southwestern Louisiana, USA, within the Gulf Coast Basin. It consists of Louann Salt that intruded through overlying sedimentary sequences of Tertiary and Quaternary age. The dome forms an asymmetric structure with a steep northern flank and a gently dipping southern limb Nelson and Fairchild [

39]. The salt core is overlain by a cap-rock complex composed primarily of anhydrite, limestone, and minor shale, formed through dissolution and reprecipitation processes at the salt–sediment interface Nelson and Fairchild [

39].

The main density contrasts responsible for the gravity anomaly are summarized as follows: the salt core has an average density of 2200–2250 kg/m3, the cap rock reaches 2600–2700 kg/m3, and the surrounding sediments range from 2400–2500 kg/m3. These contrasts, approximately 400–500 kg/m3, are consistent with the amplitude and wavelength of the observed gravity and FTG anomalies. The positive gravity response over the cap-rock zone and the negative anomaly above the salt mass confirm the vertical density inversion typical of Gulf Coast salt domes.

This structure provides an ideal case for testing gravity and Full Tensor Gravity (FTG) inversion methods due to its well-defined geometry and documented subsurface characteristics. Measurements of the gradiometric field (FTG) were acquired from 3 to 6 July 2008, by Bell Geospace Inc. [

40].

The values of the vertical component of the gravitational field in the study area were derived by integrating the tensor components and improving the accuracy of the result with ground-based gravity measurements [

40].

3.2. Gravimetric Data

Before being able to apply the Euler Tensor Deconvolution (ETD), it is necessary to obtain the horizontal components of the gravitational field, as well as to remove the residual effect of the vertical component.

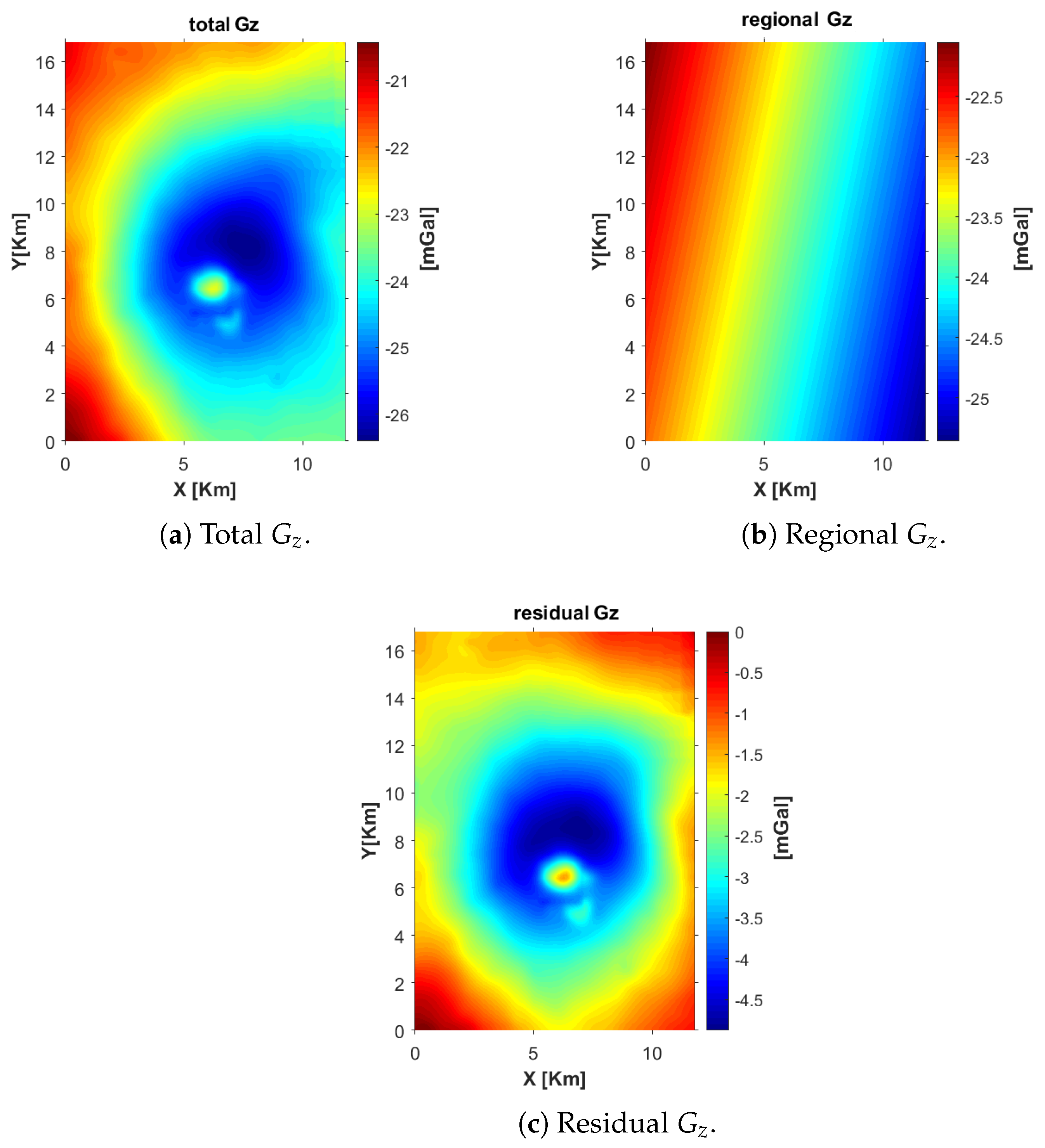

3.2.1. Residual of the Vertical Component

The residual is obtained by modeling the regional effect with a plane derived through the least squares method. The resulting geometric expression is shown in Equation (

19).

The residual of the vertical component was computed by subtracting the regional field, which represents the long-wavelength background gravity signal associated with deep crustal structures and broad density trends. This regional component was estimated by applying a second-order polynomial surface fitting to the observed gravity data, ensuring that only wavelengths larger than the expected dimensions of the Vinton Dome were captured. The subtraction isolates the short-wavelength anomalies related to the salt structure itself. The contrast between these three datasets—observed, regional, and residual—can be observed in

Figure 3, where the residual field clearly delineates the boundaries of the salt dome.

3.2.2. Horizontal Components

The horizontal gravity components ( and ) are not directly measured but are computed from the Full Tensor Gravity (FTG) gradients and the vertical component () using spectral differentiation and integration methods. These reconstructed fields are employed solely for modeling purposes, as they provide complementary directional information that enhances inversion resolution but are not standard observables in exploration practice.

Following Mickus and Hinojosa [

41], and under the assumptions of harmonic potential fields, uniform sampling, and constant observation height, the components of the gravity-gradient tensor can be estimated from gravity data by spectral differentiation, where Fourier-domain operators convert spatial derivatives into multipliers. However, this procedure is numerically ill-posed: each derivative multiplies the spectrum by

, so computing second derivatives (the tensor components) amplifies noise approximately by

. In addition, the process typically requires upward or downward continuation, which further destabilizes the high-wavenumber content and introduces edge effects. In the Fourier domain, differentiation corresponds to multiplication by

or

; thus, second derivatives scale with

,

, and

, explaining the strong noise magnification when attempting to synthesize

from gravity data.

For this reason, we do not rely on gradients synthesized from gravity alone. Instead, we use directly measured FTG data and perform a joint inversion of the measured FTG and gravity fields. In our workflow, gravity provides long-wavelength sensitivity to regional structure, while measured FTG preserves short-wavelength information and directional constraints. Their combination reduces non-uniqueness, improves boundary definition, and stabilizes the inversion compared with using gravity (or gravity-derived gradients) alone.

Table 1 shows the equations used to obtain the horizontal gravitational components.

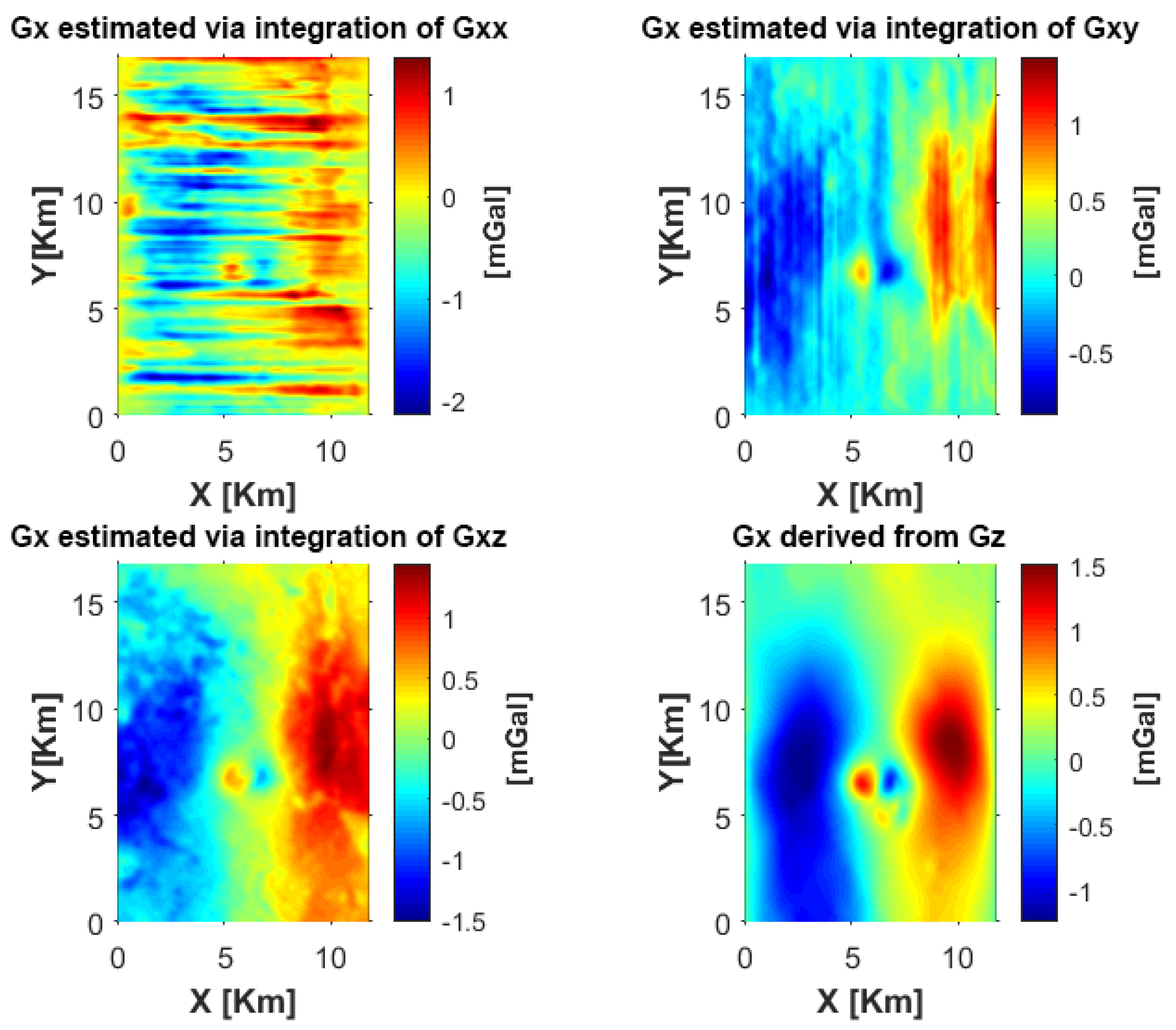

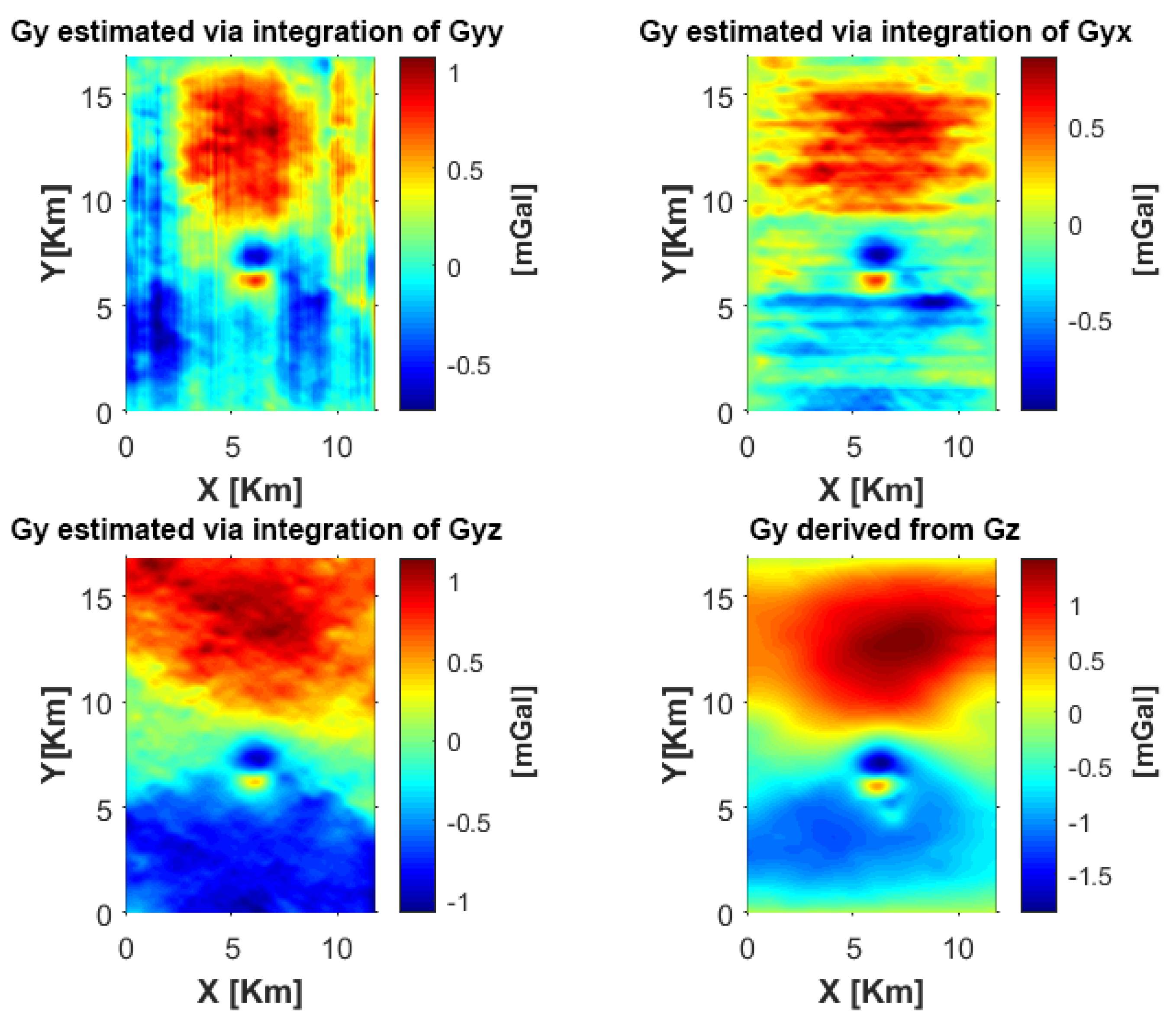

The results of the application of the two methods to compute the mentioned horizontal components are shown in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5. In them, it is clear that the estimations from the gravitational field have a greater content of low wavenumbers than those estimated through the gradiometric tensor. In the same way, the maps obtained from the integration in the wavenumber domain have a greater content of high wavenumbers.

3.2.3. Wavenumber Enrichment

The results obtained from the integration of the cross derivatives and the consecutive derivatives were unsatisfactory. Therefore, only the components derived from

and from

and

were retained. Because each component contained information dominated by either high or low wavenumbers, we applied the methodology proposed by Bell Geospace [

40] to combine them. To achieve this, we computed the amplitude spectra of both data sets and determined a cutoff wavenumber that served as a threshold for merging the results. Wavenumbers lower than this threshold were extracted from the fields derived from

, whereas the higher wavenumbers were incorporated from the derivatives of the tensor’s vertical components.

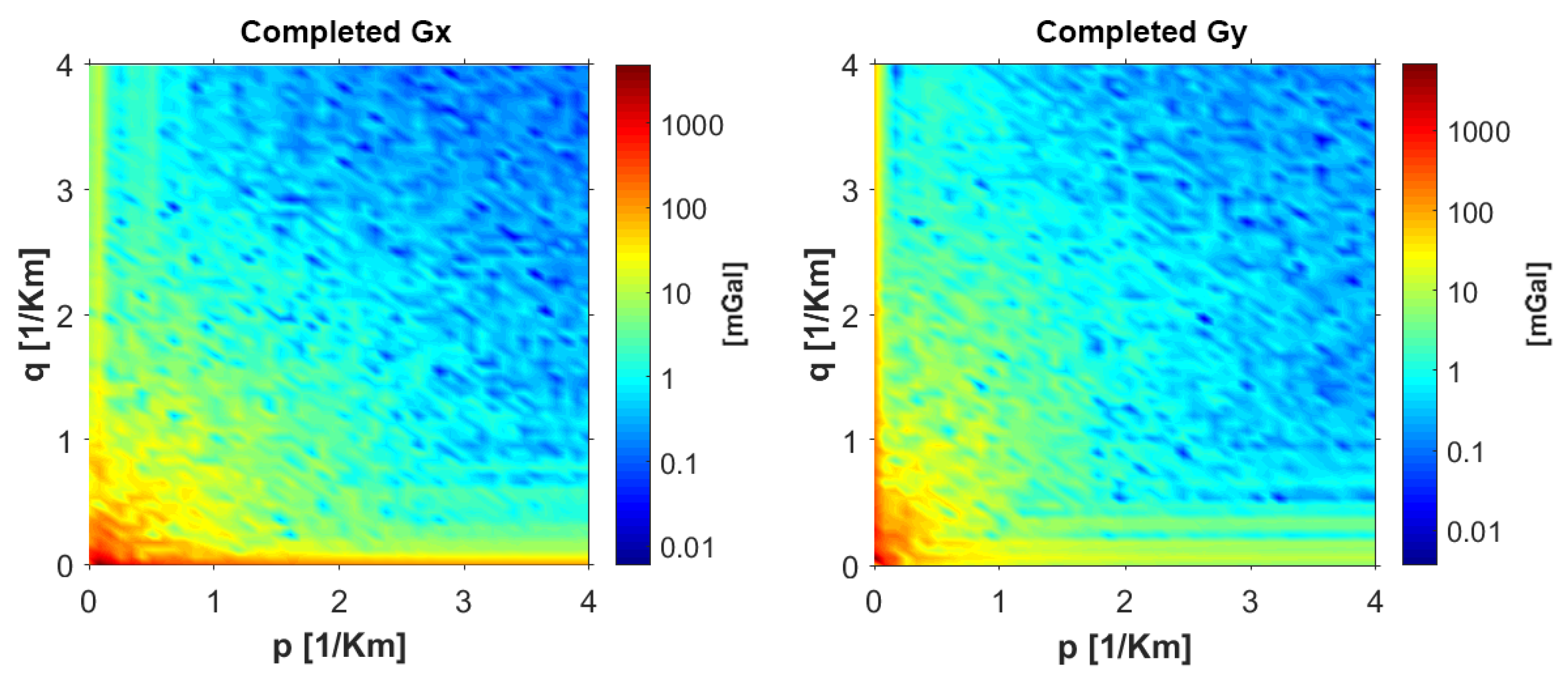

The amplitude spectra of the combined components are shown in

Figure 6. To generate the new horizontal components, the cutoff wavenumbers for the

x and

y directions were determined as 1.4050 × 10

−4 [1/km] and 1.7856 × 10

−4 [1/km], respectively. The corresponding amplitude spectra of the fused components are presented in

Figure 7. The term “completed signal” refers to the spectrally fused field obtained by adding the high-frequency components of the FTG data to the low-frequency portion of the gravity signal, thereby restoring the full wavenumber content of the horizontal gradients.

The resulting horizontal components exhibit a broader spectral range and higher wavenumber content than their predecessors. The corresponding maps are illustrated in

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8.

3.3. Initial Model (Euler Tensor Deconvolution)

To construct the initial model for the simulated annealing inversion, we first applied the Euler Tensor Deconvolution (ETD) algorithm, derived from the method proposed by Thompson [

24], to the Vinton Dome gravity and Full Tensor Gravity (FTG) data. Specifically, the horizontal gravity components (

and

) were used together with the diagonal elements of the gravity gradient tensor (

,

, and

) to estimate the position and depth of the main anomalous sources. Several window sizes were tested, producing minor variations in the calculated depths while maintaining consistent structural indices of

for gravity and

for FTG data, following Stavrev and Reid [

42]. The ETD-derived source solutions were interpolated along profiles to generate a three-dimensional density-contrast model, which served as the initial configuration for the inversion.

The initial model consists of an ensemble of rectangular prisms arranged in four stacked blocks whose lateral dimensions increase with depth, forming a pyramidal structure that approximates the geometry of the Vinton Dome. This configuration compensates for the natural decay of potential-field amplitudes with depth and significantly reduces the number of prisms, thereby decreasing computational time. Densities were assigned as density contrasts rather than absolute values, using the depth–density relationship of Nelson and Fairchild [

39] to quantify the contrast between salt, cap rock, and surrounding sediments.

And considering that

,

and

, the following matrix equation follows

Following a similar procedure for the gravitational vector, the following system is obtained

In both cases, the system is solved for the source positions and for the values of the environment field B. It ought to be remarked that in each system, a structural index N that is linked to the geometry of the source must be used.

In this work we use the procedure by Zapotitla-Roman [

10], by first applying the ETD, and we keep the horizontal components of the solutions so to later substitute them in Equations (28)–(30).

These equations have been obtained by applying the ETD to the gravitational field, thus obtaining a better estimation of depth.

By applying the previous algorithms, we obtained the following solutions depicted in

Figure 9.

From these solutions, we proposed the discretization of a volume, as shown in

Table 2.

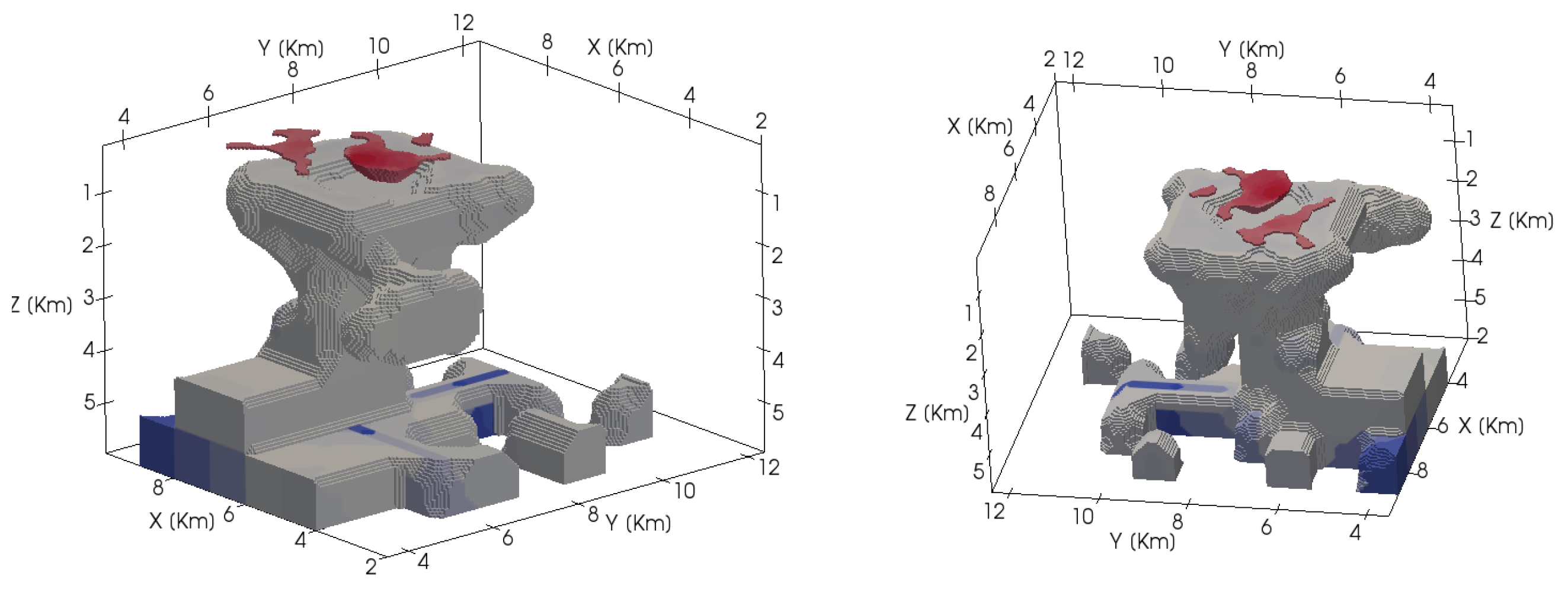

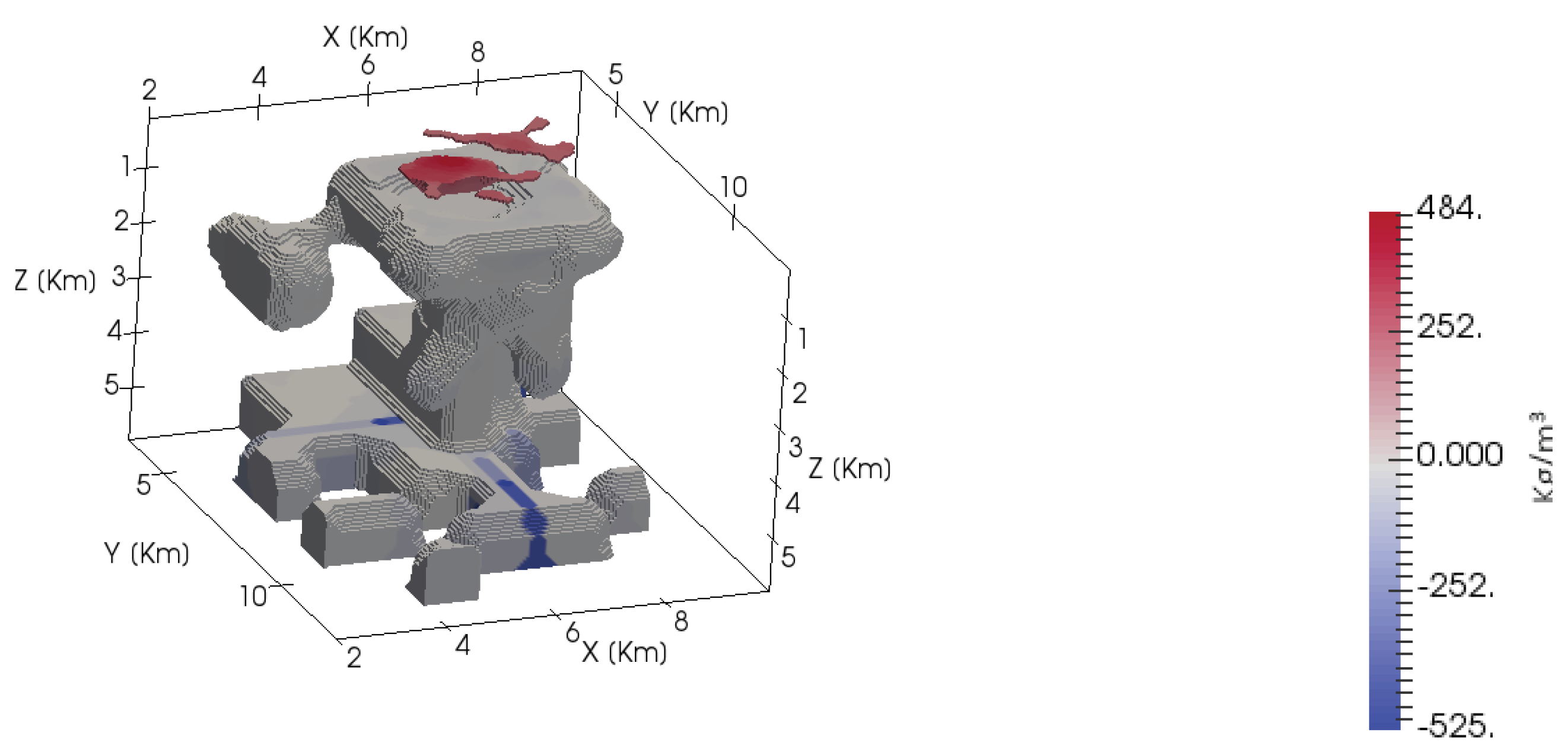

From the solutions found through ETD, the model is interpolated (

Figure 10). The color scale represents density contrasts (kg/m

3) relative to the encasing sediments. The higher-density cap-rock and lower-density salt materials are clearly differentiated but should not be interpreted as absolute densities.

3.4. Inverse Problem

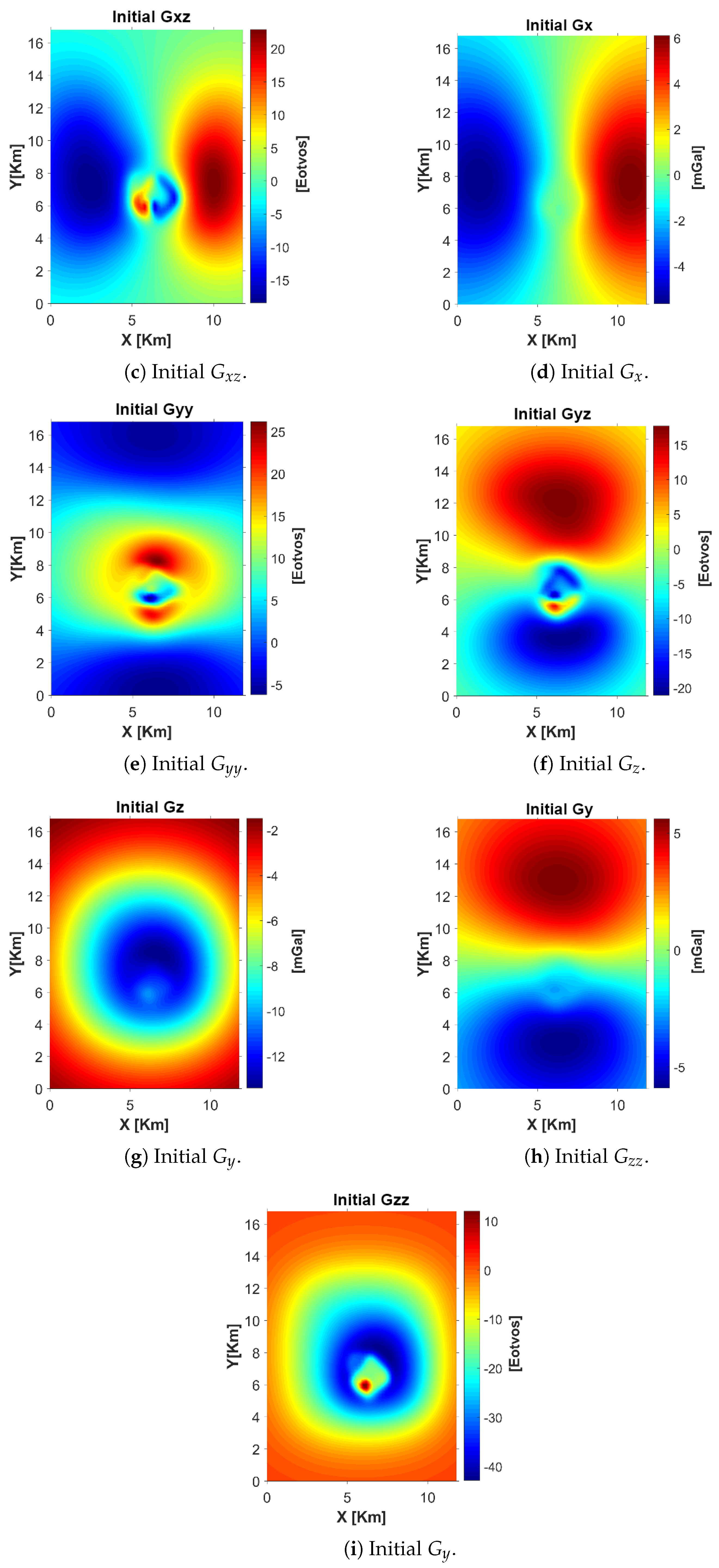

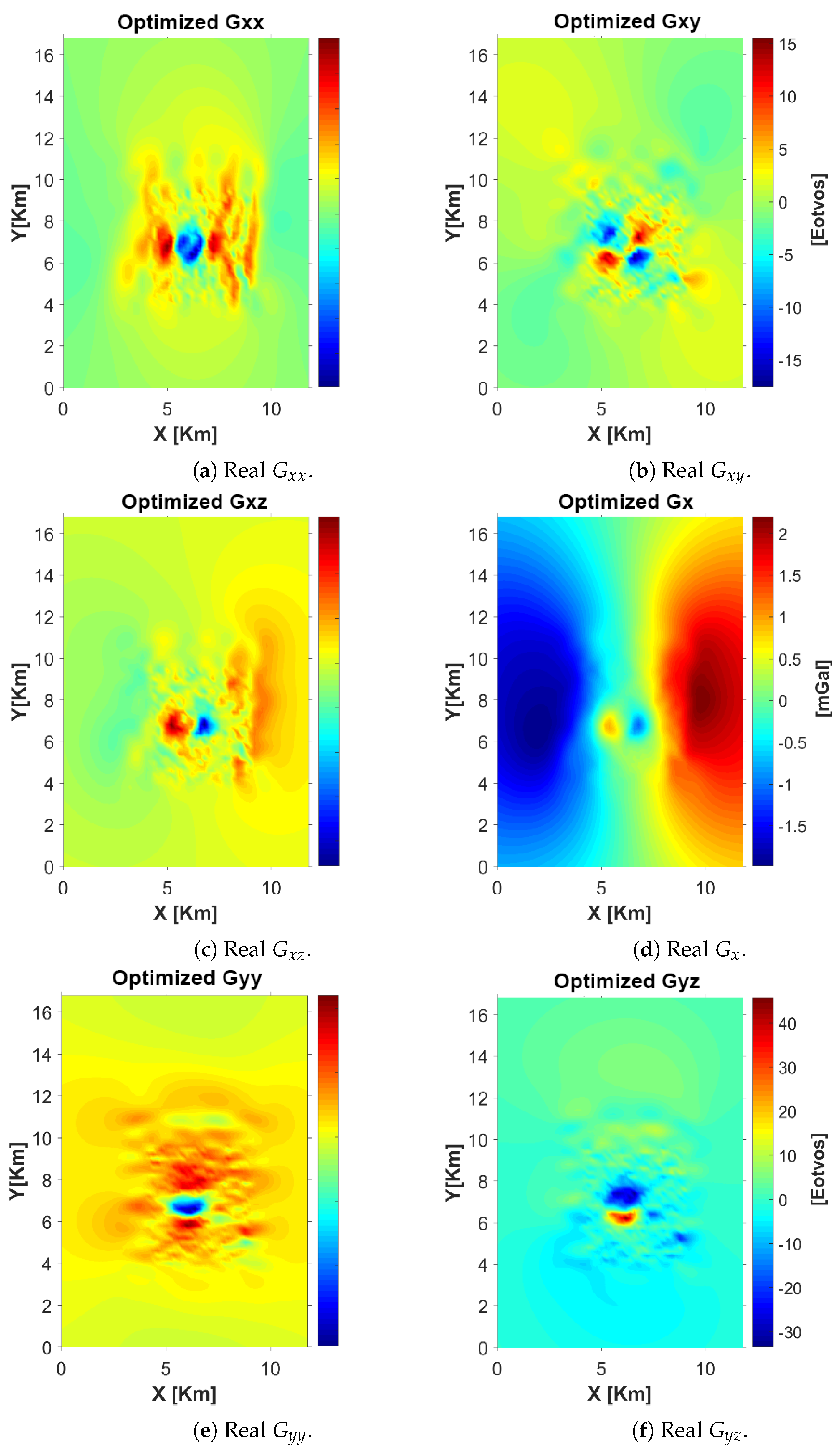

The initial synthetic data (

Figure 11) were generated from a forward model based on the prism ensemble shown in the previous subsection, using the theoretical gravity and FTG responses computed with the analytical formulas of Nagihara and Hall [

35] for rectangular prisms. These synthetic datasets were used to validate the inversion algorithm and ensure convergence before applying it to the real data.

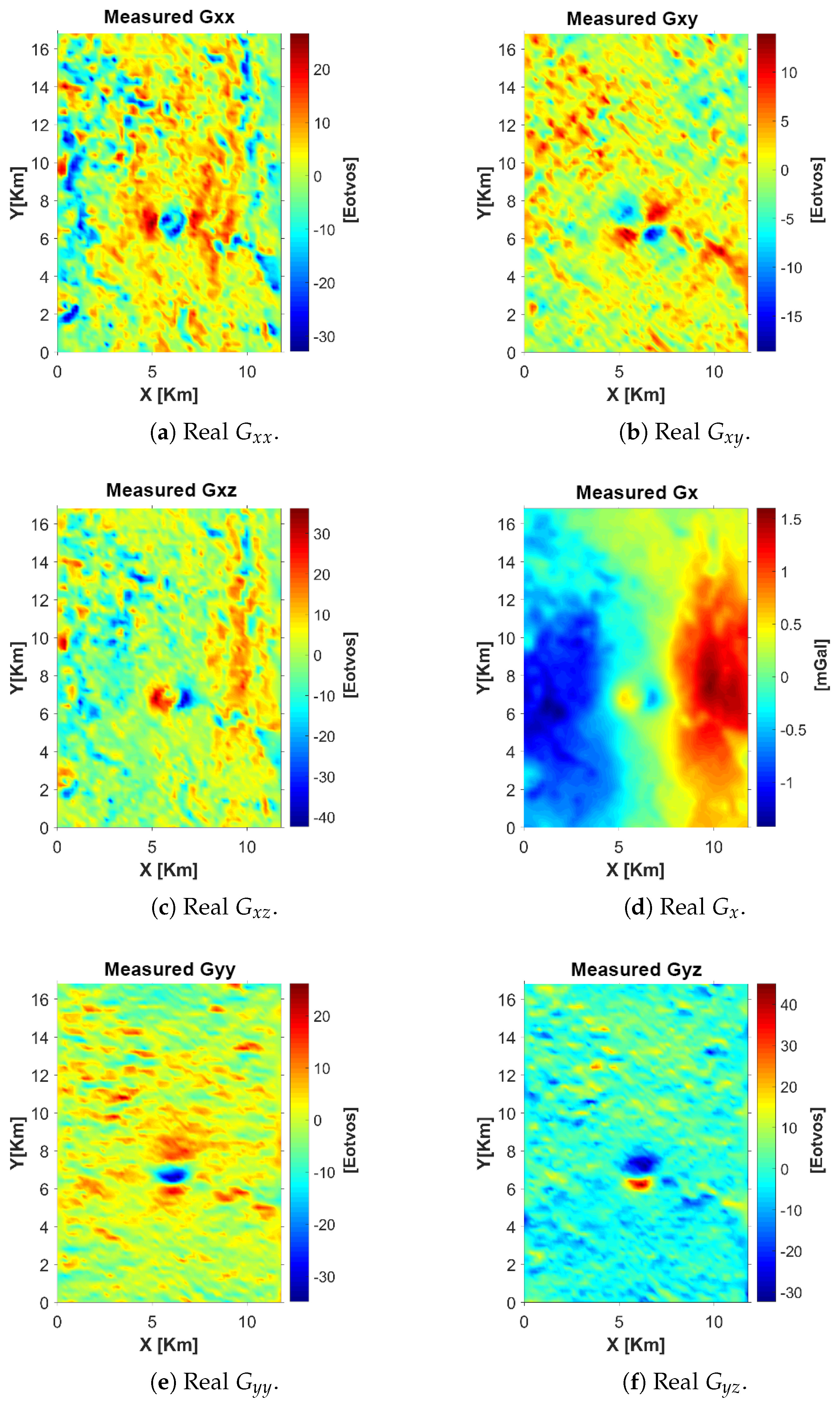

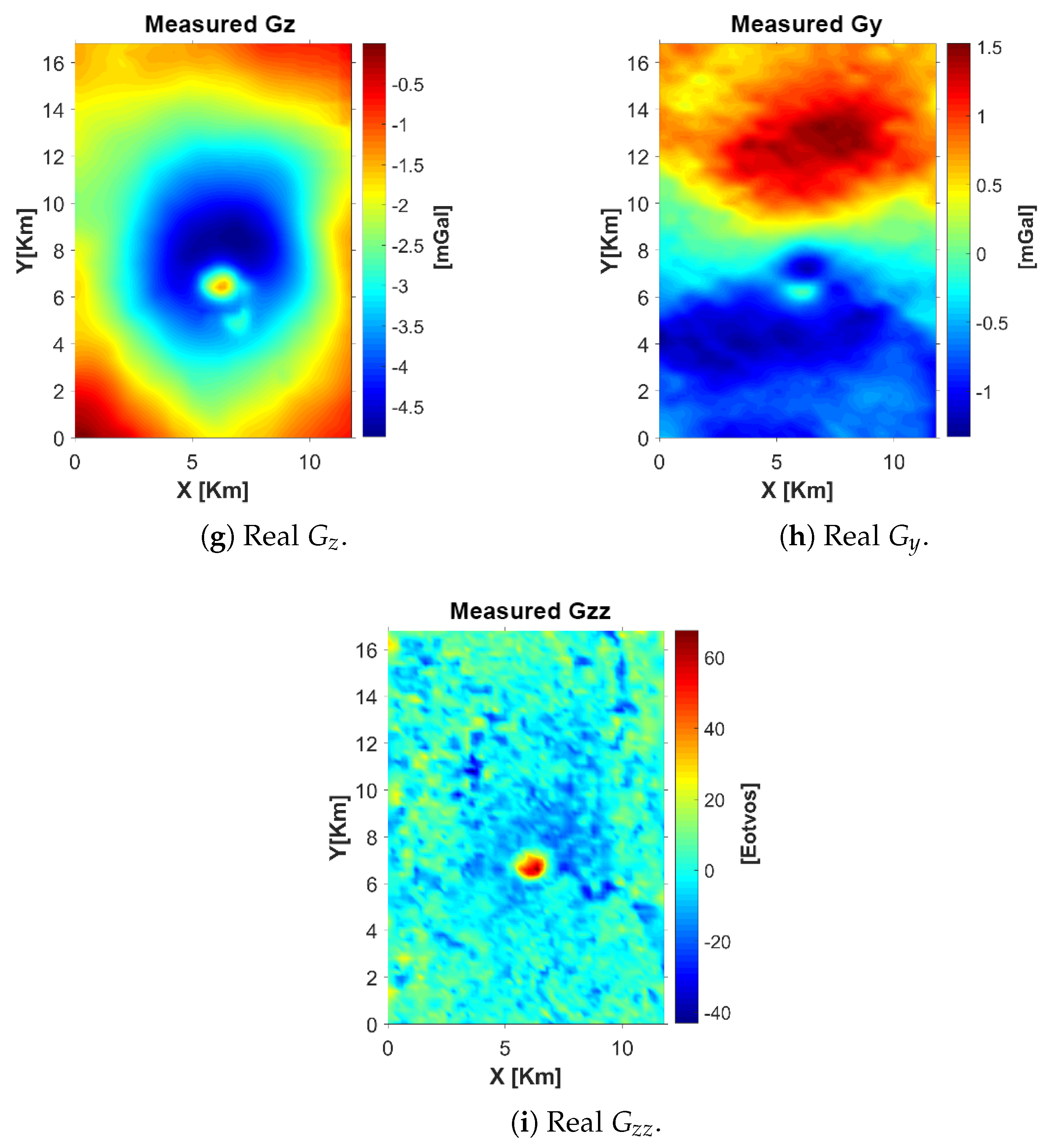

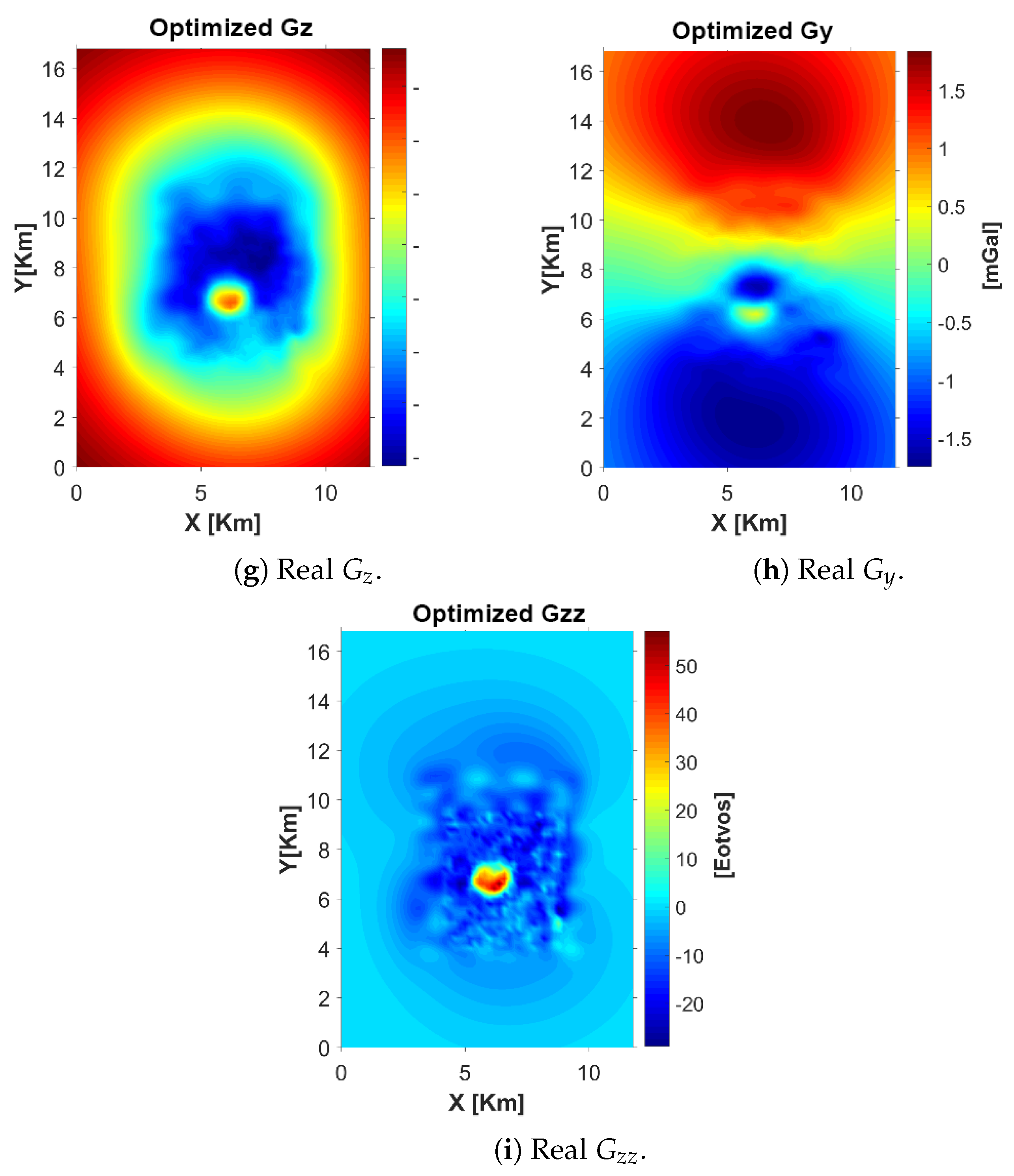

The real dataset (

Figure 12) used in this study corresponds to the FTG survey acquired by Bell Geospace (2008) over the Vinton Dome area in Louisiana, USA. Measurements were obtained using an airborne Full Tensor Gradiometer, a high-resolution instrument equipped with three orthogonal pairs of accelerometers mounted on rotating disks. The survey consisted of 53 flight lines and 17 tie lines, with average line lengths of 16.7 km and 11.7 km, respectively. Flight-line spacing was 125 m near the survey center and 250 m toward the edges, while tie lines were spaced 1 km apart.

The vertical gravity component () was derived by integrating the tensor components and refined using ground-based gravity readings. To maximize spectral consistency, the tensor signals were filtered with a high-pass filter and the gravimetric data with a low-pass filter, combining their complementary high- and low-frequency contents. This fusion produced a broader spectral signal suitable for joint inversion.

The available datasets were previously corrected by the provider for Full Tensor Noise Reduction, free-air effects, and topography.

The complementary ground-based gravity measurements were obtained from a local network of 43 observation points distributed across the central portion of the Vinton Dome area, with an average spacing of approximately 500 m between stations. The positional accuracy of each station was better than ±0.5 m, and gravity readings were accurate within ±0.05 mGal. These data were used to constrain the long-wavelength component of the

field and to validate the airborne FTG-derived vertical gravity. Although airborne Full Tensor Gravity (FTG) data inherently contain noise due to aircraft motion, Bell Geospace (2008) applied proprietary corrections, including full-tensor noise reduction, terrain adjustment, and free-air correction, which significantly improved the vertical gravity accuracy. The resulting

precision is estimated to be within 3–5 Eötvös, consistent with the specifications reported by Bell Geospace [

40] for high-resolution FTG surveys. Regarding density contrasts, realistic values were adopted based on core and log-derived measurements compiled by Nelson and Fairchild [

39] and regional Gulf Coast data. The salt core exhibits densities between 2200–2250 kg/m

3, the cap rock 2600–2700 kg/m

3, and the surrounding clastic sediments 2400–2500 kg/m

3. The contrast range of approximately 400–450 kg/m

3 used in the inversion reflects these measured properties and aligns with published geophysical models of the Vinton Dome and similar Gulf Coast salt structures.

Topographic corrections were applied using in-flight altimetry data and an average density of 1.8 g/cm3, while free-air corrections were referenced to the elevation of the flight lines. The Full Tensor Noise Reduction process ensured that only consistent variations present across all tensor components were retained, effectively suppressing noise and preserving genuine geological signals.

Cost Function

We considered two options for the cost function. Both proposals compute it as a linear combination of the missfit according to the

norm of each component, as shown in the equation:

Using the simulated annealing algorithm, we discovered the coefficients’ values that maximize or minimize the value of

within a set of synthetic data. To achieve this, we employed a complex synthetic model simulating real data, as depicted in

Figure 13.

The values of the coefficients maximising and minimising the cost function are shown in

Table 3.

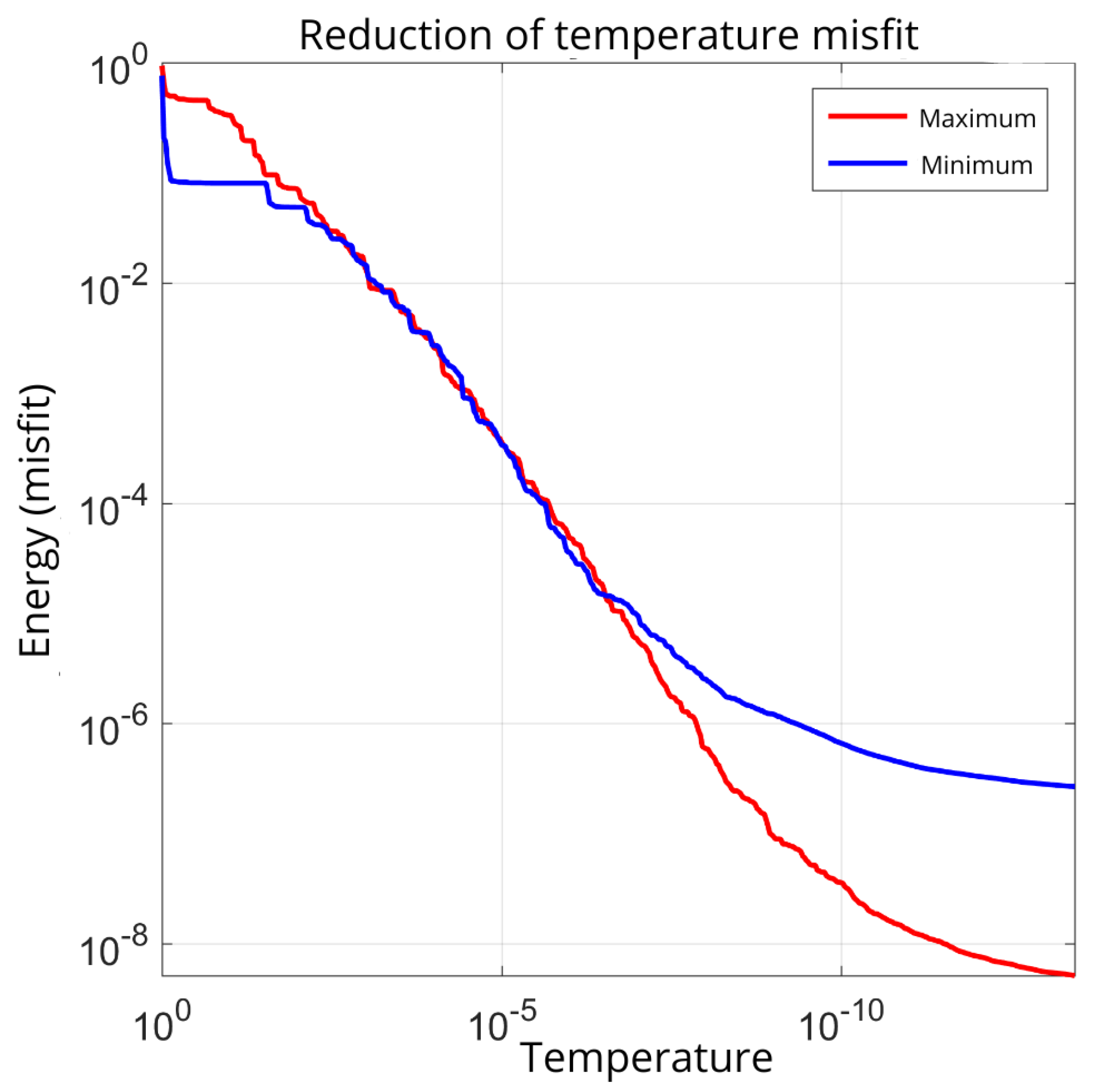

The behaviour of the cost function with both the minimising and maximising parameters is shown in

Figure 14. Clearly, the behaviour of the cost function with the maximising parameters is better at low temperatures, so these parameters are chosen for the inversion scheme.

3.5. First Inversion

The first inversion results are shown in

Table 4.

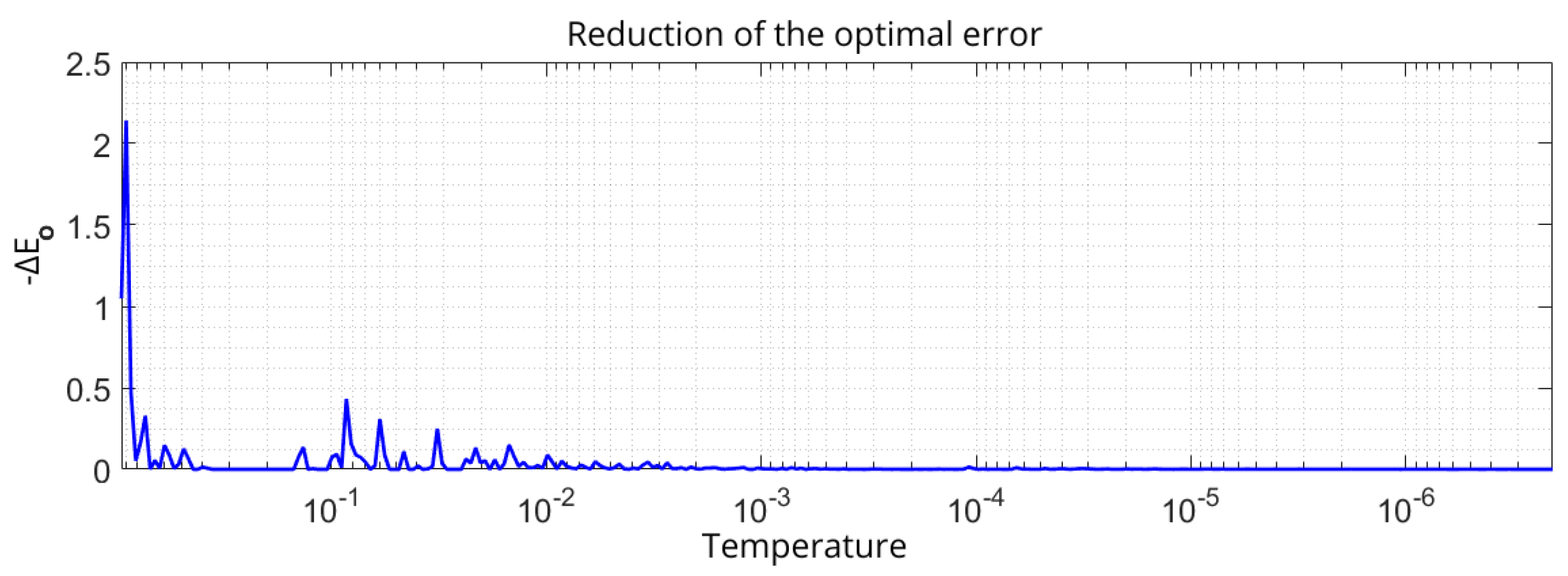

In

Figure 15, the curve illustrating the reduction in energy of the system with respect to the temperature of the Vinton Dome for the initial inversion is displayed.

On the other hand, in

Figure 16, we display the final configuration of the assembled model with prisms resulting from the first inversion of data.

Finally, in

Table 5, we present the configuration of the first inversion conducted for the Vinton Dome.

Optimal Temperature

From the first inversion, we identified the temperature interval in which the total energy decreased most significantly. Based on this observation, we performed the inversion again while maintaining this temperature for additional iterations (annealing). Before the second inversion, a mean filter was applied, and the resulting model is shown in

Figure 17.

3.6. Second Inversion

The new coefficients for the cost function can be observed in

Table 6.

The results of the second inversion for the Vinton Dome data, utilizing the filtered data from the first inversion as the initial model, are presented in

Table 7.

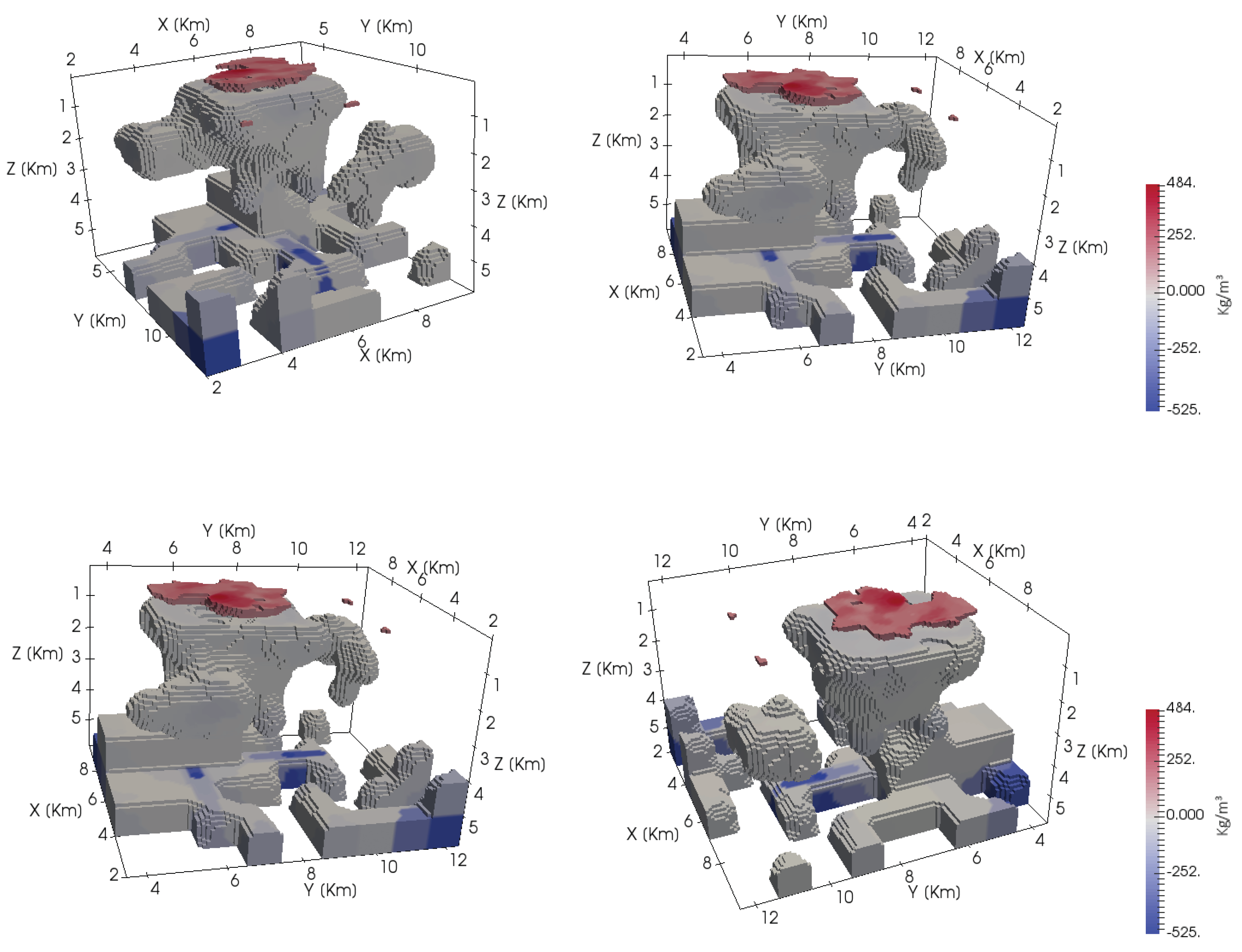

The final inversion model (

Figure 18) successfully delineates the principal salt body and its overlying cap rock. The high-density layer highlighted in red above the dome corresponds to the cap rock—an anhydrite- and limestone-rich assemblage that overlies the Vinton salt mass. Its density contrast relative to the surrounding sediments (≈+0.45 kg/m

3) is consistent with previous geophysical and drilling observations [

39].

Although the prism-based inversion yields a blocky geometry that does not exactly reproduce the smooth outline of a natural salt dome, the recovered structure effectively captures the main features of the Vinton Dome—the upward-bulging salt mass and the overlying cap rock. The apparent irregularities arise from the discrete prism representation used in the simulated annealing algorithm, which was selected to reduce computational cost while preserving the overall density distribution. The resulting morphology and depth range are consistent with published geological and geophysical interpretations of the Vinton Dome [

39].

It is important to note that, although the recovered structure exhibits a diapiric geometry with steep flanks and an upward-narrowing core, this morphology is consistent with the internal architecture of the Vinton Dome described by Nelson and Fairchild [

39]. The term “salt dome” is traditionally applied to these Gulf Coast piercement structures, which typically evolve into diapiric forms as the salt ascends through overlying strata. Therefore, the geometry shown in

Figure 18 accurately reflects the diapiric character of the Vinton Dome while remaining consistent with its regional classification as a salt dome.

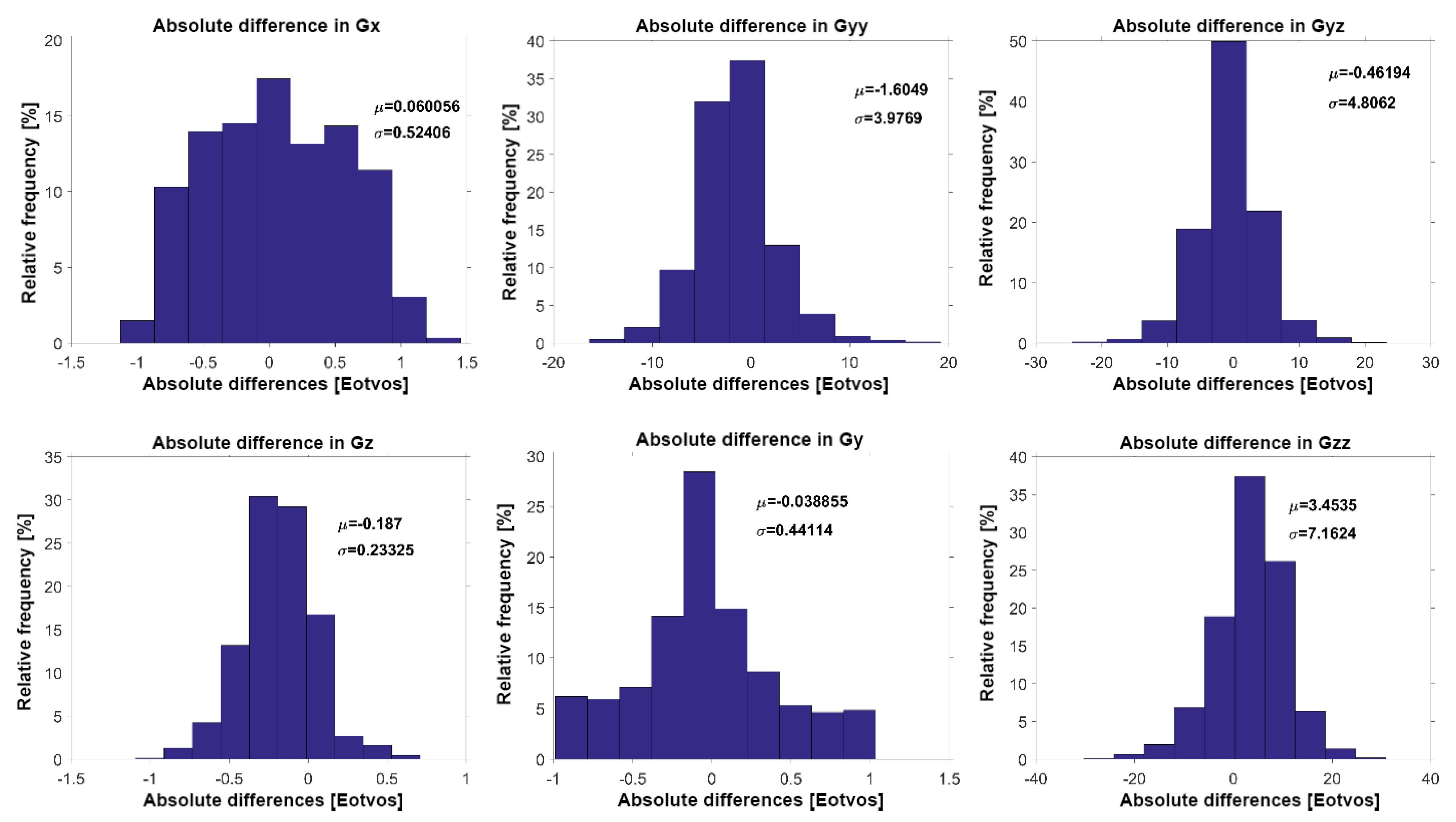

To assess the final model for the Vinton Dome, its gravity and gradiometric responses can be observed in

Figure 19. On the other hand, the differences between the optimal response (

Figure 19) and the original data (see

Figure 12) can be observed in

Figure 20.

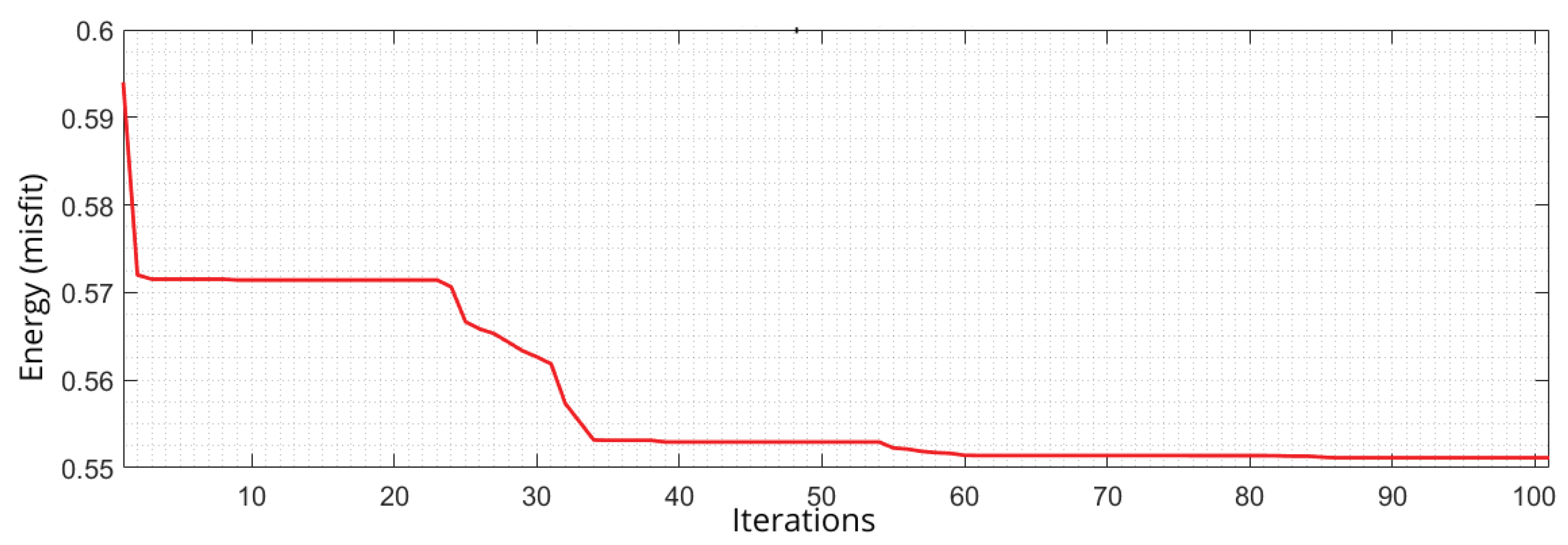

Finally, in

Figure 21, we plot the energy decrease as a function of iterations, rather than temperature, since we keep the annealing temperature constant.

4. Discussion and Final Remarks

The final inversion model indicates that the salt body extends from a depth of approximately 0.5–0.8 km at its crest to around 3.2–3.5 km at its base. These depth estimates are consistent with previously published geological and seismic interpretations of the Vinton Dome, which report salt-root depths between 3 and 3.6 km [

39,

41]. The model also reproduces the shallow high-density cap rock (0–0.3 km thick) observed in drilling data. The close agreement between the inverted and reported depths validates the joint gravity–FTG approach and confirms the stability of the simulated-annealing optimization process.

The use of Euler Tensor Deconvolution (ETD) was instrumental in constructing a robust initial model. The gradiometric data effectively delineated the lateral extent of the source, whereas the gravimetric data refined the depth estimates due to their distinct decay with distance between the source and observation points. The resulting ETD solutions tended to cluster, forming a discernible “shell” around the main body of the source.

Enhancing the high-wavenumber content in the horizontal components of the gravimetric field led to improved estimates, enabling consistent fusion of datasets from different instruments. This procedure demonstrated potential for broader application; however, it remains essential to match component amplitudes prior to fusion to prevent spectral bias.

The proposed cost function allowed the simultaneous use of nine components (six gradiometric and three gravimetric), thereby exploiting all available information and producing a model that satisfactorily fits the measured datasets. Although heuristic methods are computationally demanding, the use of parallel computing and convergence-acceleration techniques mitigated this limitation, resulting in practical run times even with increasing data volume.

Together, the adopted techniques enabled efficient inversion and produced geologically consistent results. Applying a mean filter helped remove isolated, non-physical features, while maintaining an optimal temperature range further reduced the objective function, promoted convergence, and outperformed typical local inversion algorithms that are prone to entrapment in nearby minima.

Employing the full set of gravity-gradient tensor components in the inversion, rather than relying solely on the vertical component, provided clear advantages. Complementing gradiometry with gravimetry enriched the low-frequency content, improving depth estimates for deeper sources. Nevertheless, careful management of computational cost remains crucial, as it scales directly with the number of parameters.

4.1. Recommendations and Limitations

4.1.1. Detailed

Understanding of Local Geology

Before applying the algorithm, it is essential to develop a thorough understanding of the Vinton Dome’s geology and tectonic framework, including the geometry and distribution of salt bodies and their relationships with surrounding formations and the cap rock.

4.1.2. Consideration of Cap Rock Effects

The cap rock can influence the morphology of salt structures and modify their geophysical response. When applying ETD, its presence and physical properties should be explicitly considered to minimize interpretational bias.

4.1.3. Calibration of the Initial Model

The initial model should be calibrated using all available geophysical and, where possible, well data. This ensures that the starting configuration reflects key geological characteristics—including the cap rock—and enhances the stability of subsequent ETD and inversion stages.

4.1.4. Validation with Independent Data

Whenever possible, validate results with independent datasets such as additional wells or complementary geophysical surveys. Cross-validation improves reliability and helps identify potential biases, particularly those associated with cap rock effects.

4.1.5. Geological Complexity

The Vinton Dome area exhibits complex, multi-layered geology that can limit model resolution and accuracy. Such complexity should be explicitly acknowledged during interpretation.

4.1.6. Data Resolution

The accuracy of the inversion results depends strongly on data quality and resolution. High-quality, high-resolution measurements are crucial for obtaining reliable outcomes.

4.1.7. Interpretation Bias

Interpretations may be influenced by prior assumptions or analyst bias. When feasible, compare results obtained under different model constraints or using alternative datasets and regularization parameters.

4.1.8. Algorithmic Limitations

Although effective, ETD and simulated annealing have inherent limitations:

Computational complexity: Both methods can be computationally intensive, particularly for large datasets or highly parameterized models.

Sensitivity to initial parameters: Their performance depends on starting conditions and parameter tuning (e.g., structural index in ETD; temperature schedule in SA).

Model assumptions: Deviations from theoretical assumptions or inaccuracies in input data may introduce bias.

Scope of application: Extremely heterogeneous media or highly noisy datasets may not be adequately represented.

Interpretation challenges: Correct use and interpretation require expertise in geophysics, geology, and numerical modeling.