1. Introduction

In recent years, the concept of geodiversity has gained recognition as a foundational element in the interpretation and conservation of Earth’s natural heritage. Beyond the traditional focus on biodiversity, geodiversity encompasses the variety of rocks, minerals, structures, and geomorphological processes that shape landscapes and underlie ecosystems [

1,

2]. Within UNESCO Global Geoparks (UGGps), this dimension acquires added relevance: not only does it sustain scientific inquiry, but it also provides the basis for geoeducation, geotourism, and community-based development strategies [

3]. Despite these advances, knowledge of igneous geodiversity, particularly in the tropical and Amazonian regions, remains underrepresented in the literature.

Within this framework, UGGps aim to integrate geological, natural, and cultural heritage, promoting sustainable development through education, geoconservation, and geotourism [

4,

5]. Among the core requirements of geoparks is the ability to contextualize geological heritage as a social value, fostering public understanding of geohazards, climate change, responsible use of natural resources, and the rights of native peoples’ communities over their lands [

6]. The NSUGGp promotes participatory knowledge-building processes in which geosites like Shunku Rumi become spaces for dialogue and intercultural knowledge mobilization that bridge scientific research and community-based conservation initiatives [

7,

8].

The Shunku Rumi Geosite, situated in the northeastern sector of the Napo Sumaco UNESCO Global Geopark (NSUGGp), presents an exceptional opportunity to explore and interpret a section of the Jurassic Abitagua Batholith. This geosite is not only significant for its exposures, made visible by recent road cuts, but also for the clarity with which it reveals petrographic textures, mineral associations, and structural features in a region otherwise dominated by dense vegetation and intense weathering [

7]. In contrast to the more extensively studied volcanic geological sites of the Andes, Shunku Rumi allows for direct observation of deep crustal processes, captured in the composition and emplacement of intrusive rocks.

Geologically, the Abitagua Batholith belongs to a suite of Jurassic calc-alkaline plutons emplaced along the Cordillera Real during active continental margin subduction. These granitoids, comprising diorites, monzogranites, granodiorites, and aplites, reflect multiple magmatic pulses and post-emplacement deformation events associated with the Andean tectonic regime [

9]. Although the regional framework of this batholith has been broadly described, there is a need for more detailed site-specific analyses that integrate field observations with petrographic and geochemical data. In the case of Shunku Rumi, the exposure conditions and accessibility of the site enable a multi-scalar investigation that can link mineralogy and structure to broader geodynamic processes.

This study adopts an integrative methodological approach to characterize the lithological diversity, mineral assemblages, and structural configuration of the Shunku Rumi outcrop. Through detailed field mapping, petrographic thin-section analysis, X-ray fluorescence (XRF), and X-ray diffraction (XRD) techniques, the work aims to reconstruct the emplacement history and post-magmatic evolution of the intrusive body. This approach responds to the scientific need to document geodiversity in underrepresented lithologies, and to the pedagogical imperative of translating that knowledge into interpretive frameworks for education and sustainable tourism in NSUGGp.

From a geoeducational perspective, the geosite’s configuration and accessibility present a didactic opportunity rarely available in Amazonian contexts. The visible contacts between rock types, the evidence of magmatic differentiation, and the presence of structurally displaced dykes offer valuable teaching scenarios for understanding crustal processes, tectonic deformation, mineral formation, and weathering. Moreover, this aligns with the broader objectives of the NSUGGp, which seeks to integrate scientific research with community engagement and territorial appreciation through geoeducation and geotourism initiatives [

8].

Therefore, the aim of this research is twofold: first, to document and interpret the igneous geodiversity of the Shunku Rumi Geosite based on a geological methodology; and second, to explore the potential of this geosite as a living classroom within the NSUGGp. In doing so, the study contributes not only to regional geological knowledge but also to the development of educational tools and narratives that bridge geoscience and society in an Amazonian context.

2. Geological Setting

Ecuador is geologically divided into six morpho-structural regions arranged from west to east: the Coastal Forearc, Western Cordillera, Interandean Depression, Eastern Cordillera (also known as the Cordillera Real), Sub-Andean Zone, and Oriental Foreland Basin or Oriente Basin [

10]. The study area lies within the northern portion of the Sub-Andean Zone, specifically in the eastern foothills of the Cordillera Real, directly over the Jurassic Abitagua Batholith (

Figure 1). This morphostructural context represents one of the most complex geodynamic interfaces in the Northern Andes, where tectonic inheritance, magmatism, and uplift intersect.

The Sub-Andean zone, a tectonically active corridor extending from north to south, is clearly defined by three major morphostructural domains: the Napo Uplift, the Pastaza Depression, and the Cutucú Cordillera. The Shunku Rumi Geosite is located within the Napo Uplift, which stands out as an elongated dome oriented in a northeast–southwest direction, flanked by transpressional faults on both the east and west [

11]. The Sub-Andean zone is flanked by transpressional fault systems, many of which correspond to reactivated Mesozoic normal faults that have been inverted during Andean compression. These inherited structures have played a fundamental role in sedimentation and tectonic accommodation since the Triassic–Jurassic transition [

11].

The Cordillera Real extends approximately 250 km in a northeast–southwest direction, with an average width of 60 km. It hosts several calc-alkaline Jurassic batholiths, among them Abitagua and Zamora, which were emplaced during active continental margin subduction events along the western South American plate boundary. To the west, the Cordillera Real is structurally bound by compressive reverse faults, while to the east, it transitions toward the Oriente Basin [

12]. The Abitagua Batholith occupies the lower flanks of the eastern Cordillera Real, where road cuts have recently exposed fresh intrusive rocks.

The Abitagua Batholith is an intrusive rock formation that extends approximately 120 km in length and 15 km in width [

12]. It stretches from Cosanga in the north to Río Negro in the south, situated in the foothills of the eastern Cordillera Real. It is composed predominantly of granitic rocks, exhibiting equigranular and porphyritic textures, and is crosscut by felsic dykes (aplites) and basaltic dykes up to 15 m thick [

13]. Radiometric dating constrains its crystallization between 168 and 178 Ma based on Rb-Sr, and between 169 and 174 Ma based on U-Pb zircon analyses [

9]. Recent geophysical models by [

14] reveal contrasting internal dips: northward portions incline westward, whereas the southern section’s dip eastward, with thicknesses ranging from 2 to 5 km.

Petrologically, the Abitagua, Zamora, and Rosa Florida batholiths located along the eastern Sub-Andean boundary are classified as typical I-type granitoids. These plutons are enriched in sodium (Na

2O), with significant SiO

2 variation and common hornblende content [

15]. The similarity in

87Sr/

86Sr isotopic ratios between Abitagua and other Jurassic batholiths, such as Ibagué in Colombia, suggests a shared magmatic origin linked to subduction processes that shaped the northern margin of South America during the Jurassic period [

16].

The main geological formations around the study area include the Abitagua Batholith, the Misahuallí formation, the Cosanga volcano-sedimentary deposits, and the Sumaco volcanic deposits. The Abitagua Batholith correlates with calc-alkaline plutonic bodies located in the northwestern part of South America. Faulted contacts with the Misahuallí Formation and other Cenozoic sediments indicate that tectonism from the Cretaceous period to the present played a key role in its emplacement [

9].

The Misahuallí formation, restricted to the Sub-Andean Zone, is part of a Jurassic volcanic arc that extends from northern Peru to Colombia. This formation includes lithologies such as volcanic tuffs, trachytic lavas, andesites, and dacites, dated to the Late Jurassic–Early Cretaceous [

12]. The Cosanga deposits, comprising Quaternary lahars, clays, silts, and agglomerates, exhibit medium-to-high permeability. The Sumaco volcanic includes detrital avalanches, basanites, and phonolites from the Tertiary period [

17].

Tectonically, the region is crosscut by active and paleo-active fault systems; the Río Urcusique fault is a dextral transcurrent fault, while the Jondachi fault exhibits inverse kinematics, both dating to the Quaternary period [

18]. The Quaternary Sumaco fault, delineating the eastern edge of the Napo Uplift and affecting the Sumaco volcano’s eastern flank, extends 38.8 km with a N13°E strike, a westward dip, and reverse movement [

19].

The Huacamayos fault intersects the Sub-Andean system obliquely, extending 39.6 km with a N36°E strike, dextral kinematics, and strike-slip movement [

19]. Faults in the Sub-Andean and Napo Uplift trend NE-SW, exposing Jurassic-age sedimentary sequences and volcanic arcs [

20].

In this tectonic and lithological framework, sections of the Abitagua Batholith are part of the NSUGGp, which highlights the area’s ancient magmatic activity through geosites like Shunku Rumi (translated from Kichwa as “heart stone”) (G16), Los Guacamayos Granite, Gringo’s Stone (G6), and the Waysa Yacu and Jatun Yacu Rivers (G9) [

7,

8,

21]. Shunku Rumi Geosite, located at 186,047 East, 9,931,503 South (WGS 84, Zone 18 South), 2150 m a.s.l. (

Figure 2), is an anthropogenic outcrop of granitic rock intersected by dark gray dykes, exposed by excavation to prevent landslides [

7,

21].

Recognizing that geological processes, materials, and structures are essential expressions of terrestrial geodiversity [

22], this study employs a comprehensive methodology that combines field-based structural measurements, petrographic microscopy, and geochemical analysis to document the characteristics of the Abitagua Batholith at the Shunku Rumi Geosite. The aim is to strengthen scientific understanding of intrusive igneous geodiversity and to connect it with ongoing geoeducational and geotouristic strategies implemented across the NSUGGp. The findings are intended to develop interpretive tools, educational resources, and conservation strategies for the geological heritage of this Amazonian territory.

3. Materials and Methods

This study employed a multi-scale methodological framework to characterize the petrographic, geochemical, and structural features of the Abitagua Batholith at the Shunku Rumi Geosite, located in the northwestern sector of the NSUGGp. Fieldwork was conducted during the 2023 dry season, supported by prior planning and community coordination. The methodological process was divided into four stages: field mapping and sampling, sampling preparation, petrographic analysis, geochemical analysis, and structural data processing.

3.1. Field Mapping and Sampling

Geological mapping was conducted at a 1:3000 scale following the protocols of the Instituto de Investigación Geológico y Energético (IIGE) [

23]. The study area was organized into 11 berms (B1–B11) used as reference units for sampling and lithologic control. Each sample was coded BxPy, where B is the berm number (1–11, increasing upslope) and P is the progressive sample point within that berm. A total of 24 intrusive rock samples (~1 kg each) were collected from berms B1, B2, B4, B6, B8, and B11, representing diorites, granodiorites, monzogranites, and aplites. Sampling prioritized lithological diversity, weathering gradients, and structural features, including contacts, joints, and veins. Of these, 4 were taken from country rock, 18 from dykes, and 2 from veins.

Outcrop documentation included: (1) georeferencing with a Garmin eTrex 30 GPS; (2) sketching of lithological relationships; (3) visual lithological characterization (color, texture, mineralogy, degree of weathering); and (4) documentation of mesoscopic structures using a Brunton compass. Aerial photogrammetric coverage was conducted using a DJI Phantom 4 Pro drone equipped with a 20 MP camera, enabling high-resolution imagery for mapping (

Figure 3).

Structural data (n = 134), including faults, dykes, and joints, were measured in the field and subsequently processed using Dips 8.0 to generate stereograms and rose diagrams. This data allowed the identification of predominant structural orientations and their correlation with regional fault systems.

3.2. Sample Preparation

Sample processing was carried out in the “Laboratory of Thin Sections, Magnetic Separator, and Heavy Minerals” at Yachay Tech University, as well as complementary facilities at Ikiam Amazonian Regional University (IARU) and the Escuela Politécnica Nacional (EPN). Two workflows were applied: (1) petrographic thin sections and (2) geochemical analysis.

For petrographic analysis, 16 rock samples were selected, including B1P2, B1P3, B1P4, B1P5, B1P6, B1P7, B2P1, B2P4, B2P6, B2P7, B4P2, B4P5, B4P6, B6P2, B6P3, and B11P1. Three main criteria guided the selection of these samples based on freshness, textural clarity, and lithological diversity. The thin-section elaboration was carried out in accordance with the established methodology [

24] and were prepared to a thickness of 30 µm, suitable for polarizing microscopy.

For geochemical analysis, 17 samples were selected, consisting of B1P6, B4P2, B1P5, B1P2, B1P3, B1P7, B2P1, B2P3, B4P6, B2B7, B4P5, B6P2, B2P4, B8P3, B2P6, B6P3, and B11P1. The primary criteria for selection were the representation of spatial and lithological variability. Initial drying was conducted at 50 °C for 24–72 h in convection ovens, depending on sample moisture content. Dried samples were successively crushed with a steel jaw crusher and pulverized in a vibratory disc mill to <75 µm (200 mesh). The powdered samples were homogenized and quartered using a riffle splitter, then sealed in polyethylene containers to prevent contamination. The entire procedure followed protocols adapted from [

24].

3.3. Petrographic Analysis

For macroscopic description, a total of 23 rock samples were analyzed based on their primary characteristics: color, texture, mineral composition, crystallinity, and grain size. To accurately describe and classify the hand samples, a magnifying glass, binocular microscope, and tungsten carbide-tipped scratcher were employed.

Microscopic analysis was carried out using a ZEISS Primotech T/R MAT petrographic microscope (manufactured by Carl Zeiss, Suzhou, China) at IARU. Observations were made under non-analyzed and analyzed polarized light (NAPL and APL) using 5×, 10×, and 40× objectives. Thin-section descriptions were employed to interpret paragenetic sequences and correlate microstructures with field observations. Secondary minerals such as epidote, chlorite, sericite, and carbonate phases were used to define alteration assemblages [

25].

Modal mineralogy description derives from semi-quantitative visual estimation on thin sections (n = 16) using plane-polarized (PPL) and cross-polarized light (XPL) observations. No point counting was performed; phases are listed in decreasing abundance, with estimates recorded in ~5% increments for major phases and as accessory when <5%.

3.4. Geochemical Analysis

Major elements were analyzed using X-ray Fluorescence (XRF) at IARU with a Bruker S1 Titan 600 handheld spectrometer (40 kV, 6 µA, Al/Ti filter). Samples (~6 g each) were placed in 32 mm cups sealed with 4 µm prolene films and analyzed in triplicate (60 s exposure). Mean concentrations were converted to oxides and expressed as weight percent. Data were plotted using IOGAS-64.8.3 software in TAS and AFM diagrams to infer magmatic affinities.

X-ray Diffraction (XRD) was performed at Yachay Tech using a Rigaku Miniflex 600 diffractometer. Sample holders were loaded with ~5 mg of powder, and diffraction patterns were interpreted using free Match! software via the COD-Inorganic database. Mineral identification employed peak matching, intensity verification, and refinement using the Direct Derivation (DD) method and Toraya updates [

26]. Ultimately, graphics and values representing the minerals from the analyzed samples were obtained.

Atomic Absorption Spectrometry (AAS) was used to quantify sodium, not reliably measurable by XRF. Measurements were conducted at Yachay Tech using a CONTRAA 700 spectrometer with flame atomization. The results were integrated with XRF data for full elemental profiles.

3.5. Structural Data Processing

The structural analysis was based on thirty data points for dykes, one hundred and one structural data points for joints, and three data points for faults. These data were represented in stereographic projection using Dips software to determine the preferential directions of the geological structures.

All datasets, including sketches, structural data, mineralogical, and geochemical data, were integrated to build a lithological and structural configuration of the Shunku Rumi Geosite. This integrative approach links geodiversity observations with tectonic processes and educational potential in the NSUGGp.

4. Results

The road cut at Shunku Rumi affords a continuous ~215 m long by ~110 m-high slope terraced into more than 12 berms, exposing an intrusive complex (

Figure 3). The country rock is a medium- to coarse-grained, inequigranular intrusive of intermediate–felsic affinity that ranges from monzogranite to granodiorite. Hand samples B1P6 (lowest bench) and B1P2–B1P3/B2P8 (eastern flank) display a feldspar-dominated framework with interstitial quartz and subordinate mafic aggregates; the massif is structureless at outcrop scale but pervasively jointed. Oxidized rinds along joints and shallow, friable skins point to prolonged meteoric circulation.

This framework is cut by a dense swarm of dark green to gray, steeply dipping mafic dykes (microdiorite to diorite). They strike mostly NE–SW, are decimetric to metric in thickness, and present planar, sharp contacts. Representative points include B1P3–P5 and B1P7 at road level; B2P1–P4, P7–P8 and B2P6 at the central benches; B4P2–P4, P6 and B6P2–P3 on the middle–upper benches; and B8P3–P5 and B11P1 at the top. Narrow propylitic assemblages (chlorite–epidote ± sericite, minor pyrite) are common at dyke margins, and local marginal breccias record brittle reactivation after crystallization. The dykes form competent sheeted bodies that exert first-order control on subsequent fluid flow.

In the lower-right sector, a localized granodiorite domain (B1P2, B2P8) extends along berms B1–B4. The granodiorite–monzogranite contact is cut by a dioritic dyke, which delineates the boundary and channels fluids. Toward the dyke-bounded margin, the granodiorite shows localized weathering within the first ~2–3 m; beyond this distance, the rock is mechanically competent. On the monzogranite side (left of the dyke), the rock is friable, locally forming arkosic zones and exhibiting kaolinized K-feldspar.

Late felsic thin dykes of aplite are volumetrically minor but chronologically diagnostic. They occupy extensional fractures, display unreactive, clean contacts, and locally bifurcate and anastomose. Samples B2P6 (central benches) and B4P5 (mid-upper west) exhibit a microcrystalline quartz + alkali-feldspar + plagioclase assemblage with equigranular, sugary textures, consistent with late, evolved fractions of the magmatic system sealing the pre-existing fracture network.

Cross-cutting relations define the following sequence: (i) emplacement of the monzogranite–granodiorite host; (ii) intrusion of steep NE–SW diorite dykes guided by the joint fabric; (iii) fluid-assisted propylitization focused on dyke margins and throughgoing fractures; (iv) late aplite injection and fracture sealing; and (v) post-magmatic brittle overprint with supergene oxidation. This hierarchy explains the mixed textures observed in the hand sample and the strong structural control on alteration mapped across benches B1–B11.

These field relationships, particularly the dominance of NE–SW, steep diorite dykes, and the late, fracture-controlled aplite, frame the specimen-scale observations presented below in

Section 4.1, and underpin the petrographic and geochemical interpretations that follow.

4.1. Lithological and Macroscopic Features

Field observations at the Shunku Rumi Geosite revealed a diverse set of intrusive lithologies associated with the Abitagua Batholith. The primary host rock corresponds to a monzogranitic intrusive body, represented by samples B1P6 and B6P1. These rocks exhibit coarse- to medium-grained textures and contain plagioclase phenocrysts exceeding 10 mm in length (as in B6P1), along with quartz grains of up to 8 mm. Dioritic dykes are the most abundant intrusive structural features, represented by samples such as B1P3 to B1P5, B1P7 to B2P4, B2P7, and B4P2 to B4P4, B4P6, and B6P2 to B11P1. These bodies are typically mesocratic, with porphyritic textures, hornblende phenocrysts (1–3 mm), and fine- to medium-grained matrices. Aplitic veins (B2P6, B4P5) and localized granodioritic bodies (B1P2, B2P8) complement the intrusive suite.

Mineralogically, the rocks display variability in plagioclase grain size and preservation state. For instance, sample B6P2 contains plagioclase crystals ranging in size from 2 to 6 mm, which are affected by weathering, whereas B6P3 exhibits finer textures with pyrite inclusions. Sample B4P5 exhibits a phaneritic texture with grains measuring less than 1 mm. In contrast, B1P2 and B1P6 display coarse plagioclase (1–10 mm), feldspar (1–4 mm), and quartz (2–4 mm). The identification of zoning in plagioclase, oxidized hornblende rims, and chloritized fracture fillings suggests crystallization under fluctuating thermal regimes and later-stage hydrothermal overprinting.

Table 1 summarizes the main macroscopic attributes of each rock sample, including lithology, alteration type, and textural parameters. These field-based observations provide the basis for the petrographic and geochemical analyses detailed in the following sections. They are essential to understanding the emplacement history of the Abitagua intrusive system within this sector of the Sub-Andean Zone. Additionally, the abbreviations for minerals, as listed by [

27,

28], are used to facilitate reading.

4.2. Petrographic Description

Petrographic analysis of sixteen representative samples provided crucial insights into the lithological and mineralogical diversity of the Shunku Rumi outcrop. These samples, selected based on texture, weathering degree, and spatial distribution, correspond to four principal intrusive rock types: diorite, granodiorite, monzogranite, and aplite. Thin-section observations were performed under both plane-polarized (PPL) and cross-polarized light (XPL), allowing for detailed identification of primary and secondary minerals, textural features, and alteration patterns (

Table 2).

Dioritic samples, exhibiting porphyritic to subhedral textures (

Figure 4a,b), with phenocrysts of plagioclase (1–6 mm), quartz (0.5–2 mm), and mafic minerals such as hornblende (1–3 mm) and biotite. The groundmass displays fine- to medium-grained intergranular textures. Alteration is moderate to strong, with the common presence of epidote, chlorite, sericite, and opaque oxides, confirming widespread propylitic alteration. Diorites often host microfractures filled with secondary minerals, reflecting post-magmatic hydrothermal overprint.

Monzogranitic sample (B1P6) exhibits coarse-grained equigranular to porphyritic textures (

Figure 4c,d) with well-defined quartz and feldspar crystals. Accessory minerals include biotite and zircon. Potassic alteration is recognized in feldspars through the development of sericite and iron oxides, particularly in weathered sections.

Aplitic rock (B2P6) presents fine-grained, microcrystalline textures (

Figure 4e,f) with high quartz and alkali feldspar contents. These bodies are interpreted as late-stage differentiates, characterized by low degrees of alteration, primarily restricted to oxides and clay minerals. Their cross-cutting relationships with other intrusive rocks indicate late-magmatic emplacement phases.

Granodiorite sample (B1P2) shows equigranular textures (

Figure 4g,h) with interlocking grains of plagioclase (up to 10 mm), quartz (2–4 mm), and subordinate K-feldspar. Mafic minerals are scarce and highly altered. In these rocks, the degree of alteration is moderate, with secondary sericite and epidote replacing plagioclase, suggesting hydrothermal circulation along microfractures.

Figure 4 below shows thin-section photographs (a–h) of four rock types determined at the Shunku Rumi Geosite.

The integration of petrographic observations with field and geochemical data supports a magmatic evolution characterized by multiple intrusive pulses, subsequent hydrothermal alteration, and structural reactivation. These features not only reveal the geological complexity of the Abitagua Batholith at Shunku Rumi but also enhance its didactic value for interpreting magmatic and post-magmatic processes in this Amazonian region.

4.3. Geochemical Composition

The geochemical characterization of the Shunku Rumi intrusive bodies was conducted using two complementary analytical techniques: X-ray fluorescence (XRF) and X-ray diffraction (XRD). While XRF provided quantitative data on major element concentrations, XRD was employed to identify crystalline mineral phases and assess the degree of crystallinity in selected samples. These analyses were essential for classifying the magmatic affinities, inferring the petrogenetic evolution of the intrusive rocks, and corroborating petrographic observations. The following subsections detail the results obtained from both techniques.

4.3.1. X-Ray Fluorescence Results

Geochemical analysis was conducted on seventeen samples using X-ray fluorescence and complementary sodium measurements via atomic absorption to determine the major element composition of the intrusive rocks at Shunku Rumi. The selected samples represent different lithologies and spatial positions within the outcrop. The results were interpreted using the Total Alkali–Silica (TAS) diagram and the AFM ternary diagram to classify magmatic affinities and evolutionary trends.

Most samples plot within the intermediate to felsic fields, corresponding to diorites, granodiorites, and monzogranites. In the TAS diagram (

Figure 5), the samples fall predominantly in the subalkaline, calc-alkaline field, which is typical of arc-related magmatism. This is consistent with the tectonic setting of the Cordillera Real, linked to Jurassic subduction processes.

The AFM diagram (

Figure 6) reveals a tholeiitic differentiation trend, suggesting fractional crystallization processes involving Fe-Mg-bearing minerals. The SiO

2 content ranges from 60% to 72%, with Na

2O + K

2O values between 2.7% and 7.3%, supporting the classification as calc-alkaline granitoids. The presence of high Na

2O levels, especially in granodioritic samples, may indicate sodic alteration or feldspar enrichment. The CaO and MgO content is moderate, consistent with the presence of mafic phases such as hornblende and biotite in thin-section analysis (

Table 2 and

Figure 4).

Geochemical variations across lithologies correlate well with petrographic and structural observations. Dioritic dykes, for example, show higher FeO and MgO contents, supporting their mafic character, while granodiorites and aplites show progressive silica enrichment and alkali increase. These patterns reflect magmatic differentiation in a zoned plutonic system intruded during successive pulses, as evidenced by cross-cutting relationships in the field.

Overall, the geochemical data support the interpretation of the Shunku Rumi outcrop as part of a Jurassic calc-alkaline arc pluton, which was affected by late- to post-magmatic hydrothermal processes. These results offer essential insights into the magmatic evolution of the Abitagua Batholith and provide complementary evidence to the structural and petrographic framework established in this study.

4.3.2. X-Ray Diffraction Results

X-ray diffraction analysis was performed on selected powdered samples to identify the principal crystalline phases present in the intrusive rocks and to assess their degree of crystallinity. This method complements petrographic observations by confirming mineral identities and detecting secondary phases formed through hydrothermal alteration.

The diffraction patterns revealed that plagioclase and quartz are the most abundant primary minerals across all samples, consistent with the petrographic identification of these phases. In dioritic and granodioritic samples, plagioclase (albite–anorthite series) showed strong, well-defined peaks, while quartz exhibited typical reflections around 26.6° 2θ. Minor K-feldspar (orthoclase/microcline) was also detected in monzogranitic samples, supporting their classification as intermediate to felsic granitoids.

Secondary minerals associated with alteration, including epidote, chlorite, and sericite, were identified in samples that petrographically exhibited propylitic and potassic alteration zones. These phases showed broad, low-intensity peaks, suggesting a moderate degree of crystallinity. The presence of hematite and goethite was also noted in weathered samples, confirming surface oxidation processes. The minerals identified are summarized in

Table 3.

Sample B1P2 (granodiorite) contains just over 50% of the concentration of albite, followed by quartz, orthoclase, and lower-concentration biotite. This aligns with macroscopic observations. Similarly, sample B1P3 (diorite) showed a concentration of more than 56% albite, 22% chlorite, 20% quartz, and less than 5% muscovite. Taken together, the assemblages indicate secondary albitization under low-grade (propylitic) hydrothermal alteration.

The XRD results reinforce the petrographic and geochemical interpretations, validating the mineralogical framework of the Shunku Rumi intrusive complex and providing key evidence of post-magmatic alteration. These results are particularly relevant for understanding the hydrothermal evolution of the Abitagua Batholith and its exposure at the Shunku Rumi Geosite.

Figure 7 shows the diffractogram of sample B1P6 (Monzogranite), which presents peaks of Orthoclase (3.77 Å), quartz (3.35 Å), albite (3.20 Å), Sanidine (2.96 Å), actinolite (2.73 Å), and muscovite (2.56 Å).

Figure 8 shows the diffractogram of sample B4P2 (diorite), highlighting peaks of chlorite (7.07 Å), quartz (3.34 Å), labradorite (3.20 Å), and augite (3.01 Å).

4.4. Structural Analysis

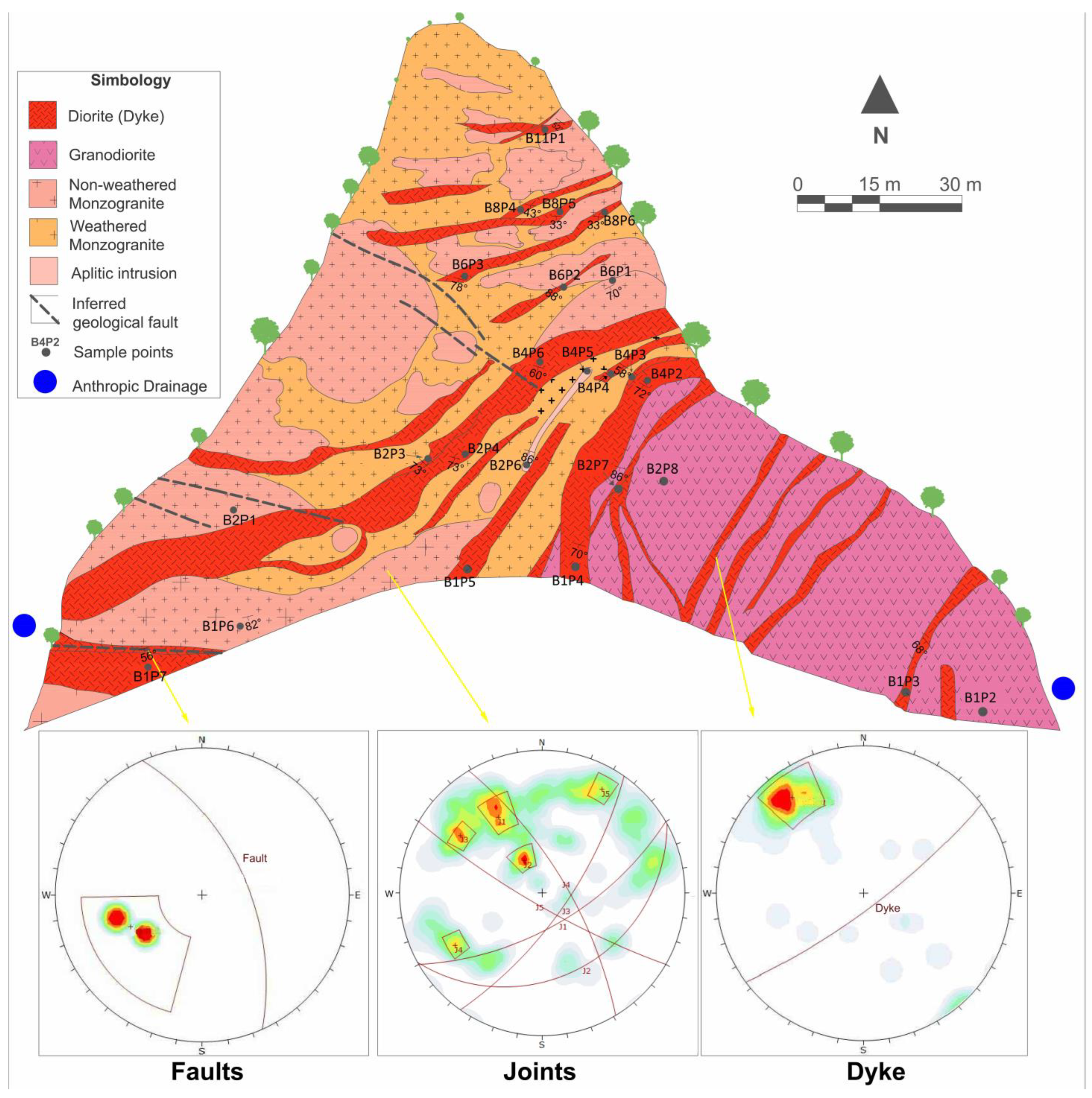

The structural analysis has been derived from a dataset comprising various structural elements, including dikes, joints, and faults, as illustrated in

Figure 9.

The structural data of the geologic faults identified during the fieldwork show a NW–SE direction, with a dip of 65° to the NE.

The kinematic analysis indicates a preferential NE-SW strike with a sub-vertical dip to the SE for the dykes. This suggests that they are emplaced in zones of weakness, such as joints, and are cut by regional structures, such as faults.

For the joints (J), five families of discontinuities have been identified: the first, second, and third families all show an NE–SW strike with dip to the SE; the fourth family has an NW–SE strike and dip to the NE; and the fifth family has an NW–SE strike with dip to the SW. The specific mean orientations of all planes are sampled in

Table 4.

These structural patterns mirror the kinematics of nearby faults such as Huacamayos, Jondachi, and Río Urcusique, which share similar trends. Their spatial relationship suggests tectonic inheritance, whereby pre-existing Andean structures influenced both intrusion and subsequent deformation of the Abitagua Batholith.

Overall, the structures at Shunku Rumi demonstrate the interaction between magmatism and tectonism. The transverse relationships, conjugate joint sets, and dykes illustrate the geodynamic context of the area. These structural features enhance the scientific value of the site and enrich its potential as an outdoor classroom for structural geology within the NSUGGp.

5. Discussion

The dioritic dykes at the Shunku Rumi Geosite predominantly contain plagioclase, hornblende, clinopyroxene, epidote, and chlorite, consistent with previous petrographic descriptions of intrusive rocks from the Abitagua Batholith [

30]. The aplite veins are dominated by plagioclase and quartz, with chlorite identified as a secondary product derived from biotite alteration. These mineral assemblages and textures are consistent with calc-alkaline intrusive rocks formed in an active continental margin. The presence of epidote and chlorite as alteration minerals suggests propylitic hydrothermal alteration typical of low-temperature, late-magmatic fluids circulating through cooling plutons [

31].

The integration of petrographic, geochemical, and structural data indicates that the intrusive bodies at Shunku Rumi, related to Abitagua Batholith, record a multiphase magmatic evolution associated with Jurassic subduction processes along the northern Andean margin [

32,

33]. These processes generated I-type calc-alkaline granitoids [

16] that were subsequently affected by hydrothermal alteration, the epidote–chlorite–sericite mineral assemblages observed in thin section confirm a propylitic alteration environment linked to post-magmatic fluids, illustrating the thermal and chemical evolution of the Abitagua Batholith. Such mineralogical transformations offer valuable geoeducational opportunities to explain magmatic evolution and hydrothermal systems in field settings.

Geochemically, the rocks from Shunku Rumi plot within the calc-alkaline to high-K calc-alkaline series, supporting a subduction-related origin typical of continental arcs [

9]. The compositional variation between monzogranite, granodiorite, and diorite indicates sequential emplacement of magmatic pulses with progressive differentiation [

34]. Fractionation of plagioclase and mafic minerals, coupled with late-stage enrichment in silica and alkalis, accounts for the observed trends in the major-element diagrams. These features parallel those documented in equivalent Jurassic intrusions of the Zamora and Misahuallí regions, reaffirming a coherent Andean arc magmatism during the mid-Jurassic [

35].

The structural analysis reveals that dykes and joints are preferentially oriented NE–SW and NW–SE, paralleling regional fault systems such as the Jondachi and Cosanga faults. Dyke emplacement was controlled by pre-existing brittle structures that acted as conduits for magma ascent during transpressional deformation [

36]. This configuration mirrors the tectonic stress field documented in other segments of the Northern Andes, suggesting that the emplacement of Abitagua Batholith at Shunku Rumi Geosite coincided with the early stages of compressional reactivation that affected the Eastern Cordillera and Amazonian foreland [

37].

The Shunku Rumi Geosite offers an exceptional natural section through the internal architecture of the Abitagua Batholith. Here, visitors can observe a continuum of magmatic, tectonic, and hydrothermal processes preserved within a single outcrop, illustrating the dynamic evolution of an ancient Andean magmatic system. The coexistence of coarse-grained monzogranites, granodiorites, and dioritic dykes demonstrates the complex interplay between magmatic differentiation and intrusions. This diversity of lithologies, including these intrusive rock types, provides a tangible record of the transition from deep-seated plutonic crystallization to shallow hydrothermal circulation. So, some geological concepts that are often difficult to convey in classroom environments can be explained in the field [

38].

From a geoeducational standpoint, Shunku Rumi represents an open-air laboratory where the geological history of the northern Andes can be reconstructed and communicated to students and the public (

Figure 10). The clear field relations, visible alteration, mineralogical contrasts, and textural features facilitate interpretive learning about magmatic differentiation and tectonic stress. By integrating these elements into guided tours, interpretive trails, and workshops, the site promotes experiential learning that bridges academic research with local community engagement. In this sense, geoeducation experiences have been carried out at this geosite, primarily with NSUGGp’s guides from the Yuyaiwa Pushak Runakuna (‘Guides with Knowledge’) group [

8]. This dual approach aligns with UGGps strategies that emphasize the didactic translation of scientific data into heritage narratives [

39].

In addition to these activities, the elements of the geodiversity database compiled in this research will serve as a practical educational resource for strengthening the training of local tourism guides, including the Yuyaiwa Pushak Runakuna, as well as university students and educators. The petrographic, geochemical, and structural information gathered throughout this study also offers useful inputs for the future preparation of geological guides, interpretive brochures, and outreach materials to support science communication and social outreach. Furthermore, these datasets will be incorporated into forthcoming interpretive resources developed collaboratively with NSUGGp staff and partner universities. By making this data available for teaching and interpretation, this work contributes to capacity building and to the co-production of geoheritage knowledge between academic and local actors [

40], reinforcing the geoeducational mission of the geopark.

Within the NSUGGp, Shunku Rumi functions as a geosite that conveys the geological story of the Andean margin from subduction to uplift. The dioritic and granitic intrusions and monzogranitic host-rock visible today were once part of the magma chambers feeding Jurassic volcanic systems of the Misahuallí Formation [

35]. Their exhumation, driven by Neogene tectonic uplift and erosional unroofing [

37], links deep crustal processes to forel-day landscapes. This narrative connects the deep-time evolution of the Andean crust to contemporary biodiversity and human settlement patterns, fostering public understanding of geological time and environmental change [

41].

The combined geochemical and structural evidence supports emplacement of the Abitagua Batholith under a transpressive regime that promoted magma ascent through inherited faults. The circulation of hydrothermal fluids along these pathways resulted in alteration patterns characteristic of regional propylitic zones. This relationship between deformation and alteration reinforces the concept that tectonism not only shapes geological architecture but also enhances mineral diversity and potential geoheritage value [

42]. Such integrative understanding strengthens interpretive frameworks for geosites where structural control and hydrothermal evolution converge.

The geological diversity expressed at Shunku Rumi Geosite extends beyond its academic significance, becoming a cornerstone for promoting sustainable geotourism and community-based education within the NSUGGp. The detailed scientific characterization of its rocks, structures, and alteration patterns provides the foundation for developing interpretive materials that integrate the narratives of native peoples, local stewardship, and geoscientific authenticity [

43]. By transforming complex analytical data into accessible heritage content, the study exemplifies how geoscience can foster inclusive education and regional identity, aligning with the holistic vision promoted by UGGps.

6. Conclusions

The Shunku Rumi Geosite represents an exceptional outcrop of the Abitagua Batholith, providing insights into the complex magmatic processes that occurred during the Jurassic period. Through detailed petrographic, geochemical, and structural analyses, this study has documented the geological diversity of the geosite, identifying key igneous rock types including diorites, monzogranites, and granodiorites, as well as late-stage aplite intrusions. The mineralogical composition, with dominant minerals such as quartz, plagioclase, and biotite, is consistent with a calc-alkaline magmatic origin related to subduction processes along the Andean margin. Secondary minerals, such as epidote, chlorite, and sericite, indicate the presence of propylitic alteration, reinforcing the hydrothermal processes related to the batholith. Future work will include targeted AAS/ICP analyses on key specimens from Shunku Rumi to refine petrogenetic interpretations while strengthening geoeducation materials with updated datasets.

The structural analysis reveals that the emplacement of the dioritic dykes and associated faults at Shunku Rumi Geosite is strongly influenced by pre-existing tectonic structures, notably the NW-SE fault systems. The interaction between magmatism and tectonism has led to the emplacement of dykes within zones of weakness, which were subsequently offset by regional fault systems. This structural configuration provides valuable insights into the geodynamic processes that shaped the Abitagua Batholith and its surrounding region. These findings are pivotal for understanding the complex tectonic evolution of the northern Andes and its implications for the local geological history.

One of the primary contributions of this research is the integration of geological data with geoeducation and geotourism strategies in the Napo Sumaco UNESCO Global Geopark. Shunku Rumi’s accessibility, its clear exposure of igneous rock types, and its structural features present a unique opportunity for field-based learning and public outreach. The site serves as a natural classroom where both students and visitors can directly engage with geological processes, from magmatic differentiation to hydrothermal alteration and tectonic deformation. The educational value of this geosite is enhanced by the ability to observe these processes in situ, which complements the ongoing geoeducation programs within the geopark.

The Shunku Rumi Geosite is more than just a scientific asset; it is an essential component of the NSUGGp’s educational and community engagement efforts. The findings also contribute to the geopark’s objectives of integrating scientific research with local community development, fostering an appreciation for geological heritage, and promoting sustainable geotourism initiatives. This study highlights the importance of engaging local communities in the interpretation and conservation of geological sites, which can lead to increased awareness of geoheritage and its sustainable utilization.