Abstract

Active faults are generally defined as faults that have moved in the past and will continue to be active in the future. They are expected to cause deformation and potential disasters if they are localized close to human activities. The definition and classification of active faults are important bases for evaluating the risk. This paper summarizes and compares the history, status, and progress of their definition and classification schemes used in representative countries and regions, as well as in some relevant standards, in active fault mapping, in the construction of spatial databases, and in some other aspects. It is concluded that the current geodynamic setting, existing technical means, geological operability, application purpose, and social acceptability of active faulting hazard in a specific area comprehensively determine the selection of the definition and classification. The key parameter in defining active faults is the time limit. It usually involves four time scales, i.e., Neotectonic (post-Neogene), Quaternary, Late Quaternary, and Holocene. The definition using a short time scale, such as Late Quaternary and Holocene, is usually suitable for the plate boundary zone, which has a high strain rate, but active faults in the intraplate deformation region and stable continental region should be defined with a long time scale, such as the Quaternary and Neotectonics. In addition, the magnitude standard can determine the activity intensity of active faults, which most generally includes three classes, namely, M ≥ 5.0 damaging earthquakes, M ≥ 6.0 strong earthquakes, and M ≥ 6.5 earthquakes that may produce surface displacement or deformation. The M ≥ 5.0 earthquake is generally applicable to regional earthquake prevention and risk mitigation in many countries or regions, but the M ≥ 6.5 earthquake magnitude benchmark is generally used as the standard in rules or regulations regarding active fault avoidance. The most common classification schemes in many countries or regions are based on fault activity, which is reflected mainly by the fault slip rate and fault recurrence interval (FRI), as well as by the last activation time. However, when determining the specific quantitative parameters of the different activity levels of faults, it is necessary to comprehensively consider the differences in activity and ages of the faults in the study region, as well as the amount and validity of existing data for the purpose of classifying different active levels of faults effectively.

1. Introduction

Active faults are the result of lithospheric or crustal deformation caused by the current tectonic stress field, resulting in the reactivation of older faults or the emergence of new faults. As the main source of destructive earthquakes, they signify the potential risk of fault rupture hazards and seismic hazards [1]. Those hazards mainly include surface ruptures, collapses, landslides, rockfalls, avalanches, dammed lakes, mudslides, sand liquefaction, land subsidence, ground fissures, and groundwater changes, as well as the surface displacement and ground subsidence caused by the creeping faults. They are major threats to important transportation facilities, large hydropower dam sites, nuclear plants, nuclear waste treatment sites, and densely populated urban districts, as have been experienced by several cities. The 1906 San Francisco Mw7.9 earthquake, the 1923 Tokyo Mw7.9 earthquake, the 1976 Tangshan Mw7.6 earthquake, the 1994 North Ridge Mw6.7 earthquake, the 1995 Hanshin Mw6.9 earthquake, the 1999 Izmit Mw7.6 earthquake, the 1999 Chi-Chi Mw7.7 earthquake, the 2008 Wenchuan Mw7.9 earthquake, and the 2023 Turkey Mw7.8 earthquake (https://www.usgs.gov/programs/earthquake-hazards/earthquakes, accessed on 1 July 2023), are just a few of the many examples that have caused extensive damages and human losses.

Buildings and/or infrastructures that are astride active faults are usually the biggest victims of an earthquake. It is considered that active fault avoidance is generally an effective measure to essentially prevent the risk of active faulting hazards, as adopted by several cities in western America and New Zealand [2,3,4]. To avoid the hazards of active faults to major infrastructure and project sites in the process of city planning, the exact location and the activity of the active faults should be determined. It should be known that defining active faults in the right way and selecting the appropriate classification scheme, considering the specific conditions, is the foundation for active fault identification.

Due to the different clients, application purposes, and the bearing capacity of active faulting risks in engineering, many academic societies and government regulators have developed special technical specifications and industry standards to regulate the investigation and surveying of active faults [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14]. It can be concluded that the definition and classification among them are distinct, even contradictory or confusing, making their use difficult.

Improper definitions can both exclude originally hazardous active faults, thus preventing effective risk mitigation, and add to the difficulty of active fault identification or even make it ineffective. Furthermore, classifying and assessing active faults from different perspectives constitutes a critical basis for preventing active faulting risks. Proper active fault classification is also an important means of providing an intuitive presentation of fault activity and its risks.

In this paper, we update the current active fault definitions based on our previous paper [15], classify active faults, and summarize their application in some countries in the world. The aim is to provide a valuable reference for industries and government departments to use a proper definition and develop an appropriate classification of active faults to meet their needs.

2. Definition of Active Faults

2.1. Basic Definition of Active Faults

The term “active fault” was first introduced by Lawson (1908) [16] after the 1906 San Francisco Mw7.9 earthquake. In the early 1900s, Wood (1916) [17] and Willis (1923) [18] defined a fault as an active fault when it possessed the following four basic attributes: (1) Surface displacement in the current seismotectonic period. (2) Probability and tendency of reactivation or regenerating surface displacement in the future. (3) Geomorphic evidence of modern activity. (4) Possible concomitant seismicity. Slemmons and McKinney (1977) [19] suggest that an active fault should have one of the following three types of evidence: “geological, historical, or seismic”. Specifically, when there is conclusive evidence of activity in the modern geological period and modern sedimentation, such as alluvial fan or alluvium, is cut (Figure 1d) or there has been surface dislocation in the historical period, or there is evidence of seismic activity distribution along the fault. Matsuda (1977) [20] defined an active fault as “a fault that has been active for many times in the Quaternary or late Quaternary and may be active again in the future”. Allen et al. (1974) [21] gave a time limit of 100,000 years to identify an active fault for the first time.

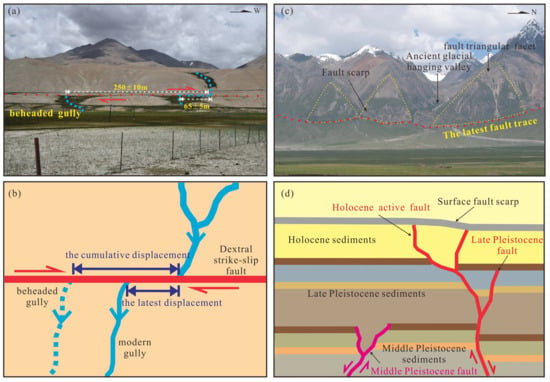

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the geomorphologic marks of surface active faults (a–c) and the age classification of active faults based on the marks of offset Quaternary deposits (d). (a) Late Quaternary gully dislocated by the Karakoram strike-slip fault. (b) A gully system was dislocated by the dextral strike-slip fault. (c) Quaternary to late Quaternary normal fault geomorphology in the north section of the Yadong-Gulu rift in southern Tibet. (d) Determining the age of an active fault based on the ages of dislocated sediments.

In the above studies, it has been emphasized that the accumulated dislocation marks during the late Quaternary period are key for identifying active faults since one single dislocation of the sedimentary layer or geomorphic surface is not always caused by active faulting. For example, the cumulative dislocation process of gullies or river systems can indicate the deflection of active strike-slip faults (Figure 1a,b), while the fault facet on the basin-mountain boundary and the fault scarps cutting through the late Quaternary geomorphic body are often the geomorphic indicators of active normal and reverse faults (Figure 1c).

2.2. Time Limit of Active Faults

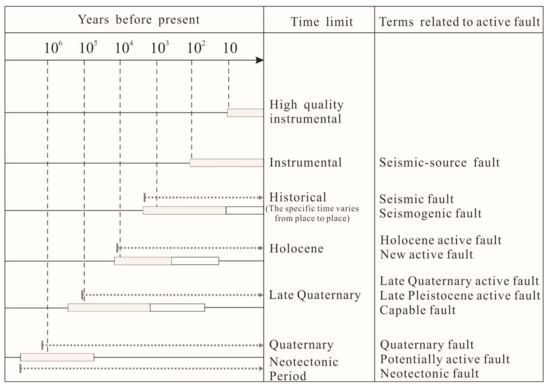

The main focus of the divergence in the definition of an active fault is the time limit (or time window), that is, exactly the past activity of the active fault, which is also the primary problem facing the identification of an active fault. In the early definition, more emphasis was placed on “faults that have been active for many times in the recent or latest tectonic stage”, and there was no clear time limit. It is common to use terms with relatively vague time intervals such as “recent geological period”, “current or present”, “young” and “historical”. This leads to different time limits for active faults in geology, seismology, engineering geology, and other industries and relevant laws, regulations, and specifications due to different understandings or use purposes [22]. Therefore, the difference in the definition of “active fault” is mainly reflected in the time limit of “the latest tectonic stage” [14,23,24]. According to the existing definitions in the world, the time limit of active faults is mainly concentrated on four different time scales: “Holocene, late Quaternary (since late Pleistocene or middle Pleistocene), Quaternary, and Neotectonic (since Pliocene or Neogene)” (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Time scale of active faults and corresponding terminologies (revised from [25] Gürpinar, 1989).

The time limit in the definition of active fault essentially reflects the history of fault activity, that is, to judge whether it will resume or continue its activity in the near future by understanding its activity from the past to the present, so it is the criterion for determining active fault, not the definition itself [23,26]. Although the time limit is critical for identifying fault activity, it cannot directly determine whether the fault will be active in the future. According to Wallace (1986) [27], human activities and engineering construction are most concerned about the possibility and risk of future activities of faults, that is, “whether the faulting or tectonic deformation process will continue and cause disasters within the period of concern of human society”. For example, for the site selection of major projects such as dams and power stations, the most important concern is whether fault activity and disasters will occur within their design service life (usually on the scale of 100 years), as well as the risk. Therefore, it is not scientific to artificially assign a fixed time limit for the definition of an active fault. The more universal definition should be “fault that can still be active in the future of human concern” [28]. In recent years, this concept has been widely accepted, for example, in the definition of an active fault in the new version of “Geological Vocabulary” in the United States: “faults that have been active recently and may still be active in the future” [29]. The definition used in the USGS seismic glossary is “faults that may produce seismic activity at some time in the future, especially those that have been active once or more in the past 10 ka” (Earthquake Glossary-active fault [EB/OL]. http://earthquake.usgs.gov/learn/glossary/?term=active%20fault, accessed on 1 July 2023).

When considering risks, the core of active fault is “the possibility of future activity”. The time limit in the definition should be open rather than a fixed value. In engineering applications, especially for standards, specifications, and legislation that emphasize preciseness and operability, the definition of the active fault must give a clear time limit to be operable. In this case, the relatively reasonable and scientific time limit of an active fault should be determined according to the project needs and the project life concerned, and after comprehensive consideration of the regional geodynamic setting and tectonic environment, application purposes, actual needs for disaster prevention and mitigation, and geological operability and other factors [23,24]. If the service life of the project is 100 years, it can be emphasized that “faults may be active in the next 100 years”. If the active faults in the site area are mainly the faults that have been active during the late Quaternary, we can focus on “faults that have been active during the late Quaternary and may still be active in the next 100 years”.

2.3. Terms Related to Active Faults

The initial definition of active fault is simple, but due to different understandings in defining the time limit, seismogenic capacity, and potentiality of hazard, as well as different requirements in engineering practice, many definitions and related terms have emerged. The following table shows some of the most frequently encountered terms (Table 1).

Table 1.

The related terms of active faults and their definitions and applications.

3. Classification of Active Faults

Active faults are defined by the need to recognize or identify fault activity. They are classified for assessing the faulting hazard, namely, to predict the potential faulting hazard and the degree of this hazard. Initially, classification was proposed when selecting the sites of nuclear power plants, when people found it necessary to classify or rate fault activity and implement appropriate countermeasures. In practice, similar active faulting hazard assessment issues are also encountered in urban planning and development. Therefore, the proper classification of known and newly discovered active faults has already become a prerequisite for finding the most effective response to active faulting hazards.

Prior to the 1970s, due to the limitations of knowledge about active faults, the classification schemes were rather simple. According to Albee and Smith (1966) [50], fault activity reflects only one single state, but the activity level is variable and can at least be distinguished into strong, medium, and weak activity. Nichols and Buchanan-Banks (1974) [51] distinguished active faults into four descending categories according to their movement frequency in the last 0.5 Ma–50 ka, 50–5 ka, and 5 ka (Table 2). Matsuda (1969) [52] also suggested that based on earthquakes, active faults can be divided into seismic faults and seismogenic faults, and based on movement patterns, they can be divided into creep-slip (creep movement) faults and strick-slip (seismic movement) faults. The former is characterized by constant, slow movement, generally producing no earthquake or only small earthquakes; the latter is characterized by sudden, rapid displacement (generally realized as strong or large earthquakes), generally producing no demonstrable displacement when the faults are locked (manifested by a lack of strong seismicity) and are therefore called seismogenic structures [53,54].

Table 2.

Active fault classification schemes of the New Zealand Geological Survey Institute.

Since the 1970s, as the investigation of active faults continued to deepen, active fault classification has matured and refined. Although a uniform scheme has not been reached yet, the most common practice is to classify active faults according to fault activity, last activation time, kinematics property, and fault scale. The classification by kinematics property is consistent with the fault type classification in traditional structural geology and is not discussed in further detail. In practical applications, single indexes, such as (i) fault activity, (ii) last activation time, or (iii) a combination thereof, are the most frequently used indexes. Among representative schemes globally regarding active fault classification, the more widely accepted and practically useful ones fall under four schemes, which are elaborated on in the succeeding paragraphs.

3.1. Fault Activity Schemes

The qualitative indexes of fault activity classification include the level of geomorphological significance of the fault and the displacement amplitude of geological bodies. The quantitative indexes mainly include slip rate, strong seismicity frequency, or earthquake recurrence interval (also referred to as “fault recurrence interval”). In the early years of active fault research, due to the limited availability of quantitative data, classification relied more on qualitative indexes.

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) (1972) [55] identified the four types according to movement rate and level of geological–geomorphological significance (Table 3). The U.S. Atomic Energy Commission (U.S. AEC) (1973) [5] recognized faults as active (in the narrow sense), capable, and dead, based on fault activity and manifestation. Grading Codes Advisory Board and Building Code Committee (1973) [56] classified faults into three types with degrading risk levels based on their relationship with earthquakes: active faults, potentially active faults—which include high-latency and low-latency faults, and inactive faults (Table 3). This scheme was also applied in the early seismic zoning efforts in California.

Table 3.

The active fault classification scheme of engineering project construction field in America.

Over time, as more quantitative data were acquired, slip rate and earthquake recurrence interval have gradually become the main criteria for classification.

3.1.1. The Slip Rate Criterion

The fault slip rate represents the cumulative rate of strain energy of the fault and is the main quantitative indicator of the fault activity. Therefore, it has always been the key parameter in the quantitative study of active fault and fault hazard assessment. Therefore, the classification of active faults based on fault slip rate helps distinguish the difference in fault activity intensity.

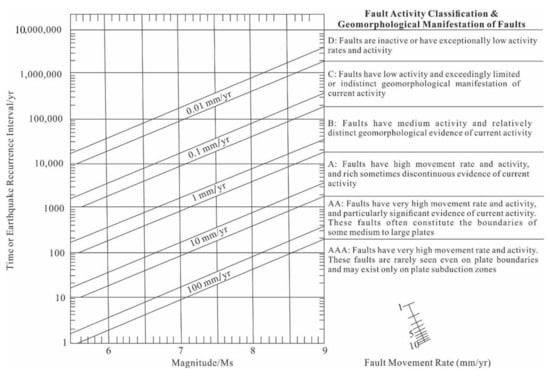

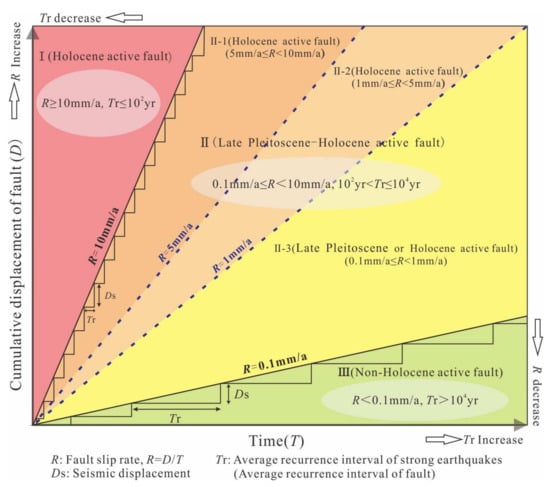

The most representative in this respect is given by Slemmons and dePolo (1986) [57] based on the fault slip rate and the correlation between it and the recurrence interval of large earthquakes and the cumulative displacement during the late Quaternary period. The quantitative indexes include the average recurrence interval of earthquakes and the average slip rate of the fault. The scheme grouped active faults into six different levels, namely, AAA (extremely strong), AA (strong), A (moderately strong), B (medium), C (weak), and D (extremely weak) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Classification scheme using fault slip-rate as the main index (after Slemmons and Depolo, 1986 [57]).

This classification scheme is still widely accepted and fairly reasonable up to the present day. Its main shortcoming, however, is that it targets active faults on a global scale. That is, instead of considering the distinction of activity among different types of active faults, such as intracontinental strike-slip faults, normal faults, and reverse faults, it uses a uniform quantitative criterion to classify them. When used in practical applications, the resulting activity ratings of reverse and normal faults could be lower than their real levels. Hence, further subdivision and modification would be necessary according to the fault type and regional active tectonics in the studied area.

3.1.2. The Fault Recurrence Interval Criterion

The Fault Recurrence Interval (FRI) criterion describes the earthquake frequency of an active fault. As shown by the fault activity classification scheme proposed by Slemmons and Depolo (1986) [57], FRI is generally positively correlated with the fault slip rate. That is, a fault with a high slip rate means a strong earthquake recurrence frequency, and vice versa. So, this index also represents an important quantitative indicator for evaluating fault risk.

The guideline for planning land development on or close to active faults established by the New Zealand Ministry for the Environment offers a representative example in this regard. This guideline provided a detailed scheme of classifying active faults according to the average time interval of surface rupture repeatedly caused by active faults to highlight the future risk of faults and clarify whether building or land development programs of different importance levels need to avoid an active fault or for land development to be allowed in an active fault-affected zone [58]. Under this scheme, faults are divided into six types (I–VI) (Table 4). Faults with recurrence intervals greater than 125 kyr are considered inactive in New Zealand because the definition of the active fault adopted by New Zealand is “the fault that has undergone surface dislocation or deformation since about 125 kyr ago and may still occur in the future” [59].

Table 4.

Mean recurrence interval classification scheme for active faults.

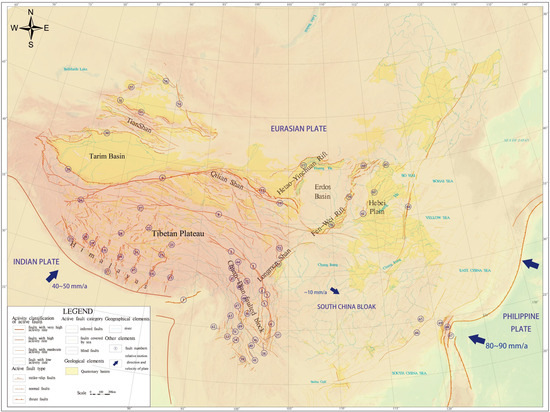

3.2. The Last Activation Time Schemes

The formation time of the current tectonic stress field under different geodynamic backgrounds is often different. For example, it can be as old as about 15 Ma on the relatively stable North American continent and as young as about 0.5 Ma in the California area of the United States [23]. The current tectonic stress field in the Chinese Mainland is closely related to the latest tectonic deformation and uplift process of the Tibetan Plateau under the continental collision of the India-Eurasia plate, mainly formed about 10–8 Ma ago [60,61,62,63]. This period is the so-called neotectonic period [49]. During the neotectonic period, with the continuous deformation and movement of the lithospheric plate, the fault zone must also be in the process of continuous evolution. The activity of some faults may gradually weaken or tend to stop, while the activity of other faults may gradually increase or new faults may appear. Therefore, faults with different active ages can be distinguished and classified based on the most recent dislocated strata, helping identify which faults have become inactive or tend to be inactive and which are still significantly active. The latter are usually the faults with the highest probability of reactivation. Therefore, the classification scheme of active time is often adopted by some engineering specifications and mapping guidelines, which can be demonstrated by typical examples in the United States and China (see Section 5.3 and Section 5.8 for details).

3.3. Other Classification Schemes

Apart from the representative active fault classification schemes discussed above, some authors and institutions have also proposed other unique classifications to address their respective purposes or applications.

Ding (1982) [64] suggested considering five types, according to the development stage of faults.

Juvenile: A microfracture development zone or hidden rupture zone formed in a place where the crustal shear strength is weak or where the shear stress is the most concentrated and showing no demonstrable displacement yet, often manifested by the zonal activity of small earthquakes.

Growth: A young active fault at its peak strength, often manifested by a linear fault structure with demonstrable displacement, usually with strong seismicity, frequently occurs at the end of rupture development or at the intersection with other structures.

Prime (or active stage): A mature fault zone, which implies a through-going structure at the largest available scale of a fault network that dominates the tectonic slip accommodation, comprising multiple young active faults connected together, whose seismicity differs from one segment to another but which often shows migration and transformation among the active segments.

Aging (or decline stage): A fault entering the decline stage, in which its activity is weak, is often cut or branched by younger faults and has very low seismicity and a long movement period.

Fossil fault (or dead fault): A fault that has consolidated, closed, and fully ceased to move. These faults have no seismicity at all.

The development process of active faults also approximately echoes the evolution of the activity of the faults and the progressive seismicity from weak to strong and then from strong to weak. Accordingly, distinguishing the development stages of faults is of positive value for understanding the seismic risk of faults.

The guideline for avoiding active faults prepared by the New Zealand Ministry for the Environment, in addition to the classification based on the recurrence interval of active faults, is to better determine the setback distance from active faults and take more pertinent preventive measures against the active faulting risk. Active faults are also classified into Type A, Type B, and Type C, according to the distribution of fault traces [65]:

- A:

- A well-defined fault trace of limited geographic width, typically a fewer meters tens of meters wide.

- B:

- Deformation is distributed over a relatively broad geographic width, typically tens to hundreds of meters wide, and usually comprises multiple fault traces and/or folds.

- C:

- The location of fault traces is uncertain, as they either have not been mapped in detail or cannot be identified. This is typically a result of gaps in the traces or erosion or coverage of the traces.

These classifications are all useful supplements to the more commonly accepted or traditional fault classification schemes and are of reference value for the evaluation of faulting risks and the prevention of disasters.

4. Definitions and Classifications Adopted by Representative Countries and Regions

In this chapter, we give some examples of active fault definition and classification schemes generally adopted in parts of the world where active faults are more developed and more intensively investigated, to help obtain an idea of how active faults are defined and classified in areas with different tectonic regimes.

4.1. The United States

The United States straddles the North American continent and contains many areas with significantly different tectonic settings. The northwestern state of Alaska and the western states (to the west of the Rocky Mountains) are seated on the oblique subduction–collision and strike-slip transition boundary zone between the Pacific plate and the North American plate, whereas the eastern region of the United States belongs to the passive continental margin to the west of the Atlantic Ocean. According to the plate tectonic positions and current crustal deformation patterns, continental America can be separated into four tectonic provinces: Alaska, California (or San Andreas Fault System Province), Basin and Range Province (or Large Basin Province, which includes Utah, Nevada, Idaho, southeastern California, and western Arizona), and Central–Eastern Province [66]. In Alaska, which is subjected to the NW oblique subduction of the Pacific plate toward the North American plate, the current crust shows a history of intense compressional–shearing deformation, as manifested by the widespread presence of reverse faults and large dextral strike-slip faults parallel to the subduction zone. California, which lies on a strike-slip transition zone between the Pacific plate and the North American plate, is characterized by the presence of the NW-trending San Andreas dextral strike-slip fault system, with the strike-slip faults commonly showing strong Quaternary activity [67,68]. The Basin and Range Province, which is a dispersion deformation zone subjected to a nearly NW intraplate extension, is characterized by the presence of a few hundred to a thousand small-sized but generally potentially active normal faults with earthquake recurrence intervals spanning from thousands to tens of thousands of years [69,70,71]. The central–eastern part of the North American continent, most parts of which are relatively stable regions, is prevalently characterized by the reactivation of Paleozoic to Mesozoic old structures under a nearly E–W to NE horizontal compressional tectonic stress field [72]. The active faults in this region are less developed, and the earthquake frequency is low, constituting primarily stable continental-type earthquakes [66].

The active fault definitions and classifications adopted by many countries and regions are either directly copied from or influenced by US standards or guidelines. Nevertheless, within the United States itself, active faults are defined and classified in different ways as the country spans a wide variety of active structures and activity levels, and the research perspectives and objectives also differ substantially. There have been different ideas with different focuses with respect to active fault definition and classification and their application. The definitions and classifications can often differ among different areas and industries as well. The following are the four most representative schemes in the United States:

- (1)

- An active fault is a fault that has had movement in the late Pleistocene to the Holocene. This is the most widely adopted definition in California on a plate boundary. A representative example of such a definition is in the “Alquist–Priolo Special Studies Zones Act”—renamed as the “Alquist–Priolo Earthquake Fault Zoning Act” in 1994—after the 1971 San Fernando Mw6.6 earthquake, also known as the “Alquist–Priolo Act” or AP Act” [73]. It is the first mandatory active-fault surface-rupture hazard avoidance regulation in the world. In this act, an active fault is defined as “a fault that has had surface displacement within Holocene time (about the last 11,000 years)” [37,73]. In addition to this, the “Division of Safety of Dams (DSOD) Fault Activity Guidelines” recommended defining an active fault as “having ruptured within the last 35,000 years”. It also added and defined the terms “conditionally active fault” and “inactive fault” [10].

- (2)

- Active faults are “capable ones” that have had movement since the mid-Pleistocene. This is more frequently found in the siting and construction criteria for nuclear facilities that have high geological safety requirements. For example, the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (U.S. NRC) has long used the term “capable fault” to describe a fault that has moved multiple times about the last 0.5 Ma and has moved once within the past 50 ka [6].

- (3)

- Active fault definitions with a single time limit are not comprehensive. In addition, Quaternary active faults must be classified. Considering that active faults must include faults having the potential for M ≥ 6.5 earthquakes (or for surface rupturing), due to the significantly different fault activity and predominantly long earthquake recurrence intervals in the Basin Range Province in the western United States, it is inappropriate to use one single time limit for defining an active fault. The “Definition of Fault Activity for the Basin and Range Province” released by the Western States Seismic Policy Council (WSSPC) recommended using the following definitions of fault activity in acts, standards, and guidelines to categorize potentially hazardous active faults in that physiographic province: Holocene active fault (within the last 10,000 years), now updated to be between the latest Pleistocene and Holocene (about 15,000 years B.P.), Late Quaternary active fault (about the last 130,000 years), and Quaternary active fault, formerly about the last 1,600,000 years, but now updated as about the last 2,600,000 years [36]. These definitions have been adopted by Nevada, Utah, and its capital city, Salt Lake City, in their respective guidelines for assessing the potential surface rupture hazards of active faults [74,75,76].

- (4)

- Definitions of Quaternary active faults apply throughout the country. The “US Quaternary Fault and Fold Database”, which was released by the United States Geological Survey (USGS) in 2004, identified Quaternary (since 1.6 Ma) faults and folds as potential seismogenic sources for M > 6.0 earthquakes and defined the faults as seismogenic faults that have had, and will have in the future, large intensity earthquakes (M > 6.0 earthquakes) with geologic evidence or that are likely to cause surface deformation [35]. Active faults were defined as “only those known or mapped faults that show geologic evidence of having been the source of large-magnitude, surface-deforming earthquakes (M > 6.0) during the Quaternary (since 1.6 Ma)” or the ones that are “likely to become the source of another earthquake sometime in the future”.

Some local departments in the United States also used their own active fault definitions and classifications suitable for their project safety assessment purposes. For example, the “California Division of Safety of Dams Fault Activity Guidelines” suggested dividing fault activity into three categories when performing deterministic earthquake hazard assessment related to dam safety [10], as shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

The active fault classification scheme of California Division of Safety of Dams Fault Activity Guidelines.

The 35,000-year value was selected as the criterion for defining the time limit of fault activity based on two arguments [10]: first, the Holocene (the last 10,000 years) is too short to eliminate fault activity that may affect dam stability; second, faults exhibit a wide range of average earthquake recurrence intervals, from a few decades to over several hundred thousand years. A fault that has not moved in the last 35,000 years is assumed to have a recurrence interval of ground-rupturing earthquakes of more than 35,000 years. Such a low level of activity can be negligible for the purpose of dam design.

4.2. Japan

Japan is an island country on the island arc zone adjacent to the Western Pacific subduction boundary, as well as the subduction collage site of four oceanic–continental plates of varying sizes and orders: the Western Pacific plate, the Philippine Sea plate, the Okhotsk–North American plate, and the Amur subplate in the eastern Eurasian plate. The complex plate tectonic setting in the region has given rise to a transpressional tectonic setting dominated by compression–shortening deformation but with strike-slip components [77] as well. Reverse faults and strike-slip faults are ubiquitously present. Widespread faults and frequent earthquakes have long exposed Japan to particularly active seismicity and particularly severe earthquake hazards. For this reason, Japan has always attached great importance to the investigation and research of active faults.

The research on active faults in Japan started early, at approximately the same time as in the United States. However, extensive and systematic active fault investigation and research did not take place until the 1960s. In the early days, Japanese researchers did not have a unified understanding of the active fault definition. Some proposed considering a fault as active if it had moved in the last 500,000 or 1,000,000 years [78]. However, after five years of work consisting of aerial photo interpretation and surface survey (in the original maps, the scale was 1:200,000 for active faults on land and 1:500,000 for those at sea), the Research Group for Active Faults of Japan (1980) [79] compiled the “Active Faults in Japan: Sheet Maps and Inventories”, where a fault is considered active if it “has moved continuously in the Quaternary time (about the last 2,000,000 years) and may still have movement in the future”. It is close to the definition of a Quaternary active fault. In that book, Quaternary was used as the criterion for determining the time limit of fault activity. In Japan, the topography is frequently used to define fault activity in the latest geological period, primarily formed in the Quaternary period, and the current tectonic stress field responsible for fault activity has not changed much throughout the Quaternary. This definition has been widely adopted in subsequent studies but has been challenged by some authors [80], who argued that some faults that have had movement in the early stages of the Quaternary may cease to move in the later stages and unlikely move in the future. For example, some faults in the Nara Basin that formed about 1.1 Ma may have ceased to move about 0.2 Ma. Therefore, for evaluating a project, defining the time criterion of fault activity as 2.0 Ma would be too long. Fujita (1981) [80] suggested dividing Quaternary active faults into “old active faults” that have ceased to move in the mid-Pleistocene, and “recently active faults” that have continued to move about the last 0.5 Ma.

In 1991, the Japan Active Fault Research Association published the revised edition of the “Active Fault of Japan—the Map and Explanation” [81,82,83], which included 123 publicly accessible 1:200,000 sheet maps of active faults and detailed information on 1800 active faults, together with a 1:1,000,000 active fault map of Japan and a 1:3,000,000 distribution map of active faults and earthquakes in and around Japan. However, in the newly compiled maps, active faults are still defined in roughly the same way as the Quaternary active faults in the earlier edition.

After the 1995 Hanshin earthquake, the Geological Survey of Japan launched another round of active fault mapping, which, again, performed high-accuracy aerial photo interpretation but adopted a new active fault definition: a fault is active if it has had repeated movement in an interval of a thousand to ten thousand years since the late Quaternary or the late stage of Pleistocene (primarily the last few hundred thousand years, especially about the last 200,000 years) and is still likely to move again in the future.

In 2000, a 1:25,000 GIS-based detailed digital map of active faults covering the whole land area was completed, followed by a new 1:2,000,000 active fault map of Japan [84,85]. The new definition excludes several faults that had movement in the early stages of the Quaternary but have not moved since the late Quaternary. Thus, it effectively reduced the number of faults in the new active fault map and further highlighted those that are prominently late Quaternary active. The regulatory guide issued by the Nuclear Safety Commission of Japan (NSC) (2006) [86] also adopted the late Quaternary criterion, defining a fault as active if it has had movement since the late Pleistocene (about the last 130,000 years).

In 2005, the Active Fault Research Center of Japan Geological Survey, a subsidiary of the National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology (AIST), released an “Active Fault Database of Japan” [87], which sorted out seismogenic faults longer than 20 km and with a slip rate higher than 0.1 mm/yr and presented their segmentation and related parameters. Included in this database are faults that have had repeated movement in the latest geological period and are likely to produce large earthquakes [77].

After the 2004 and 2007 Niigata earthquakes, considering the disastrous consequences of inland “straight-beneath” earthquakes (refer to an earthquake occurring at the location of the source), the Headquarters for Earthquake Research Promotion of Japan decided to launch an “active fault” mapping project in 2009. The project would take 10 years to conduct a detailed survey of the approximately 2000 active faults previously confirmed by aerial photo interpretation, establish their exact locations and distributions, and draw a more detailed set of “active fault base maps”. The purpose was to let people know how far away they live from active faults, improve the awareness of disaster prevention, and increase the seismic resistance of residential buildings (from www.xinhuanet.com, accessed on 1 July 2023). This project is reported to have been basically completed.

In addition to the term “active fault”, Japan also created the term “seismic fault”. First used by Japanese geologists in 1935 when summarizing the earthquakes in Taiwan and their geological causes, it refers to a fault “that formed on the ground surface following a large earthquake”. According to statistics, in Japan, these shallow-source earthquakes are generally M ≥ 6.5 earthquakes [88]. A seismic fault is also described as “a surface rupturing fault that appears in history following an M ≥ 6.5 shallow-source earthquake” [88]. According to this definition, there are some 20 seismic faults in Japan. Further investigations also revealed that almost all these seismic faults occur along existing active faults, which validated the premise that seismic faults are virtually faults that have had a surface rupture in history as a result of large seismic events. Later, seismic faults were renamed “surface faults” [78] and are what is known today as “seismic surface ruptures”.

4.3. Italy

Italy is situated in the subduction–collision zone between the African and the Eurasian plates. Geodynamics is further complicated by the presence of the microplate Adria, which is an indentation of the African plate inside the Eurasian one. A complex tectonic setting has been jointly created by the three tectonic zones of the southern Alpine orogeny, the Apennine–Calabria subduction arc, and the back-arc extensional zone. There are active faults in this region with different recurrence times [89], belonging to three tectonic domains with distinctly different fault activity patterns and overall occurrences: two compressional deformation tectonic domains in the north—one in the Southeastern Alps, and the other from the central-eastern section of the Apennine Peninsula to the Po plains—which are characterized by the development of blind thrust and reverse faults, and an extensional deformation tectonic domain is located in the south-central, with the main body of Apennine–Calabria Peninsula, which is characterized by a large number of normal faults and some strike-slip faults approximately parallel to the orientation of the peninsula, capable for releasing Mw > 6.5 earthquakes and to produce surface faulting [90,91]. The complex, active tectonic setting has made Italy a country with prominent and strong seismic and volcanic activities. For this reason, Italy has attached great importance to the investigation and research of active faults since the 1970s and has remained one of the leaders in Europe in this regard.

The” Italian National Institute of Geophysics and Volcanology” (INGV) and the Italian Ministry of Environment created and released their respective active fault databases that highlight different types of active faults for their respective platforms. The former was responsible for compiling and updating the “Database of Individual Seismogenic Sources” (DISS) [92], which targets seismic hazard assessment and covers seismogenic sources or seismogenic faults discovered by historical seismicity and paleo-earthquake research, which are deemed to be capable of inducing and producing Mw ≥ 5.5 earthquakes [93], as well as their geometric and kinematic characteristics and three-dimensional distribution forms. The latter was responsible for compiling and updating the spatial database named “Italy Hazards from Capable Faulting” (ITHACA), which targeted active fault-related disaster prevention in land planning and project siting [94]. It emphasized capable faults, namely, those that can generate surface displacement and potential active faults, as well as related information. It also covers the geometric and kinematic characteristics of faults and their activity rating.

Considering the active tectonic setting and the geological and geomorphological characteristics of Italy, Galadini et al. (2012) [24] recommended selecting the time limit of active and capable faults specific to the active tectonic domain in question. According to them, for the compressional tectonic domain between the southeastern Alps and the Po plains in northern Italy, which is characterized by the development of blind thrust faults and reverse faults, the “Quaternary active” definition may be used, and faults that show geomorphological and shallow surface evidence of Quaternary (about the last 2.6 Ma) activity can be considered as potentially active and capable. For the extensional deformation tectonic domain in the Apennines, central-southern Italy, as the current tectonic regime typically emerged in the mid-Pleistocene, faults that show geomorphological and shallow surface evidence of mid-Pleistocene (about the last 0.8 Ma) activity can be considered potentially active and capable. However, for both tectonic domains, a fault can be considered inactive if it is overlain by deposits or landforms older than the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM, about 24–16 ka B.P.). The LGM was used as the minimum time limit for fault inactivity because deposits of that period are widely present in Italy, and this time span can include multiple strong earthquake recurrence cycles [24].

In accordance with the Guidelines for Seismic Microzonation (GSM) [14], a fault is considered active if it has been active at least once in the last 40 ka (upper part of the Late Pleistocene-Holocene). An active fault is considered capable when it reaches the topographic surface, producing a fracture/dislocation of the ground level. This definition refers to the rupture on the main fault plain (on which there is the greatest dislocation). Active and Capable Faults (ACFs) can be classified into two categories depending on the uncertainties tied to their identification (Table 6). The main surface of rupture and related coseismic phenomena are recognized as certain. This category includes secondary tectonic structures and transfer areas between distinct segments of an ACF. The elements comprising an ACF and related coseismic phenomena cannot be mapped with certainty and/or in detail due to the absence of data or because they cannot be identified (transfer zones, gap, erosion, sedimentary cover, etc.).

Table 6.

Descriptive categories of active and capable faults and coseismic phenomena (ACF_x).

In addition, the Italian Ministry of Environment also integrated and unified published and unpublished local-scale geological information and derived strain parameters for structural and seismotectonic analyses, which enrolls the structural data relevant for seismogenic purposes and can be extended at least to the overall Quaternary time interval (last 2.58 my) [95]. The second version is in progress, which will cover the remaining Italian areas.

4.4. Greece

Greece is located to the south of the Balkan Peninsula, in the Eastern Mediterranean Sea, close to the subduction–collision zone between the Eurasian plate and the Nubian plate. It is the collage site of the Apulian, Aegean, Anatolian, and Nubian plates, as well as the interaction region between the large, more than 1000 km-long, very active, E–W-trending, dextral shear zone of the Anatolian fault zone and the N-dipping Hellenic Arc and Subduction zone. This particular tectonic setting has given rise to distinctly different tectonic domains, showing strong dispersion of deformation [66,96]. Entering the Aegean from the east, the transcurrent North Anatolian fault gradually adopts the extensional regime of central Greece toward its western end, as it passes from the North Aegean trough (NAT) to the North Aegean trough (NAB) in the north Aegean Sea [97]. In the south, the region between the Hellenic arc and the Anatolian fault zone is a back-arc extensional deformation region comprising normal faults parallel to the Hellenic arc. In the west, i.e., the broader Ionian Sea, there are three lithospheric-scale structures: The Aegean-Nubian convergence along the Hellenic subduction zone to the south, the Aegean-Apulian collision to the north, and the Cephalonia Transform Fault Zone in-between which separates and shifts the other two [66,98,99]. The dense and highly active faults in Greece make it the country with the highest earthquake frequency in Europe.

Based on the platform and the general concept of the Italian DISS, the “Greek Database of Seismogenic Sources” (GreDaSS) was built, relying on a joint project between the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki (Greece) and the University of Ferrara (Italy). Three terms are mentioned therein, namely, “seismogenic source” (primarily referring to a seismogenic fault in the paper), “capable fault”, and “active fault” [98,100,101]. According to these authors, the active faults in Greece fall under two categories, seismic and capable, which are equivalent to a known seismogenic source and a potential seismogenic source. The former are faults that have been rupturing since historical records, the latter are ones that are capable of producing Mw > 5.5 earthquakes under the current tectonic stress field [102], which actually include faults that have already become seismic, and those that are likely to become seismic in the future.

With respect to active fault classification, Pavlides et al. (2007, 2010) [98,103] suggested dividing active faults into the following six categories according to their last known movement time and activity:

- (1)

- Seismic fault: a fault that has directly caused a known significant seismic event.

- (2)

- Holocene active fault: a fault that has had displacement in the last 10 ka and generally with a relatively high slip rate.

- (3)

- Late Quaternary active fault: a fault that has had displacement in the last 40 ka. This time value was selected mainly in consideration of the upper limit of 14C dating.

- (4)

- Quaternary active fault: a fault that has had displacement in the last 2.6 Ma and generally with a relatively weak to moderate slip rate.

- (5)

- Capable fault with undefined age: a fault whose geometric and kinematic characteristics make it very likely to move again and lead to destructive seismicity in the current tectonic stress field, and is actually equivalent to a “neotectonic fault”.

- (6)

- Fault with undefined activity: a fault that is likely to remain inactive.

In the Digital Database of Active Faults in Greece, faults are considered active if they show geologic evidence for slip during the last 125,000–130,000 years, which are commonly accepted by the western United States, Japan, and New Zealand [104]. As continental Greece extensively demonstrates intraplate deformation, with long earthquake recurrence intervals ranging from several hundred to a few ten thousand years, a longer time period the Holocene would be more suitable for defining fault activity in the region (see [23,105] for the paleoseismic perspective). Accordingly, a fault is called active when it has shifted at least once during the Late Pleistocene (in the last 126,000 years or so) and can therefore be a source of future earthquakes (https://oasp.gr/energa-rigmata-tis-ellados, accessed on 1 July 2023).

4.5. New Zealand

New Zealand is an NE-trending island country situated on the subduction–collision zone between the Australian and the Southwestern Pacific plates. The large NE-trending dextral strike-slip faults comprising the Alpine fault zone, which represents the above plates boundary, runs through the New Zealand Islands, separating it into two distinct tectonically active areas: the Northwestern and Southeastern ones [66]. To the northwest, most of the active faults are distributed in and around the NE-trending Taupo volcanic rift zone. To the southeast, where faults are more widely present, the contraction-shearing deformation, characterized by the occurrence of reverse and strike-slip faulting, plays the dominant role. Located at the boundaries of tectonic plates with strong activity and frequent earthquakes, New Zealand has become the first country to conduct specific investigations and descriptions of strike-slip faults after earthquakes.

Comparatively consistent active fault definitions are adopted within New Zealand [106]. In both (i) the “Active Fault Guidelines” compiled by the geology research institute of Nuclear Science Limited (GNS Science), at the request of the New Zealand Ministry for the Environment for regulating land planning in and around locations containing active faults, and (ii) the latest 1:250,000 New Zealand Active Fault Database (NZAFD250) published by GNS Science, a fault is defined as active if it has had surface displacement or deformation in the last 120–128 ka and is still likely to have displacement again in the future [58,59,65,107,108]. This definition is equivalent to a late Quaternary active fault defined in Table 1. The 120–128 ka value was selected as the time limit criterion for fault activity mainly because late Quaternary deposits are widely present in New Zealand and this time span has often been used in published geological maps. Therefore, it can help provide a good age basis for determining fault activity [108]. The only exception is the Taupo volcanic zone in the northern part of New Zealand Island, where a fault is considered active if it has had displacement in the last 25 ka. That is because volcanic and fluvial deposits from 25 ka or younger have overlain the older deposits and landforms, and all traces of the latest active structure, the Taupo rift, are found in the younger deposits [108].

In participating in the active fault database project organized by GEM, New Zealand drew on the classification scheme of the database but also made some changes to the time and slip rate according to its own characteristics. The fault movement time classification scheme only contains four categories: Historical (1840 A.D.–1000 yr B.P.), Holocene (1.0–11.7 ka B.P.), and Late Pleistocene (11.7–125 ka BP). The slip rate (V) classification scheme also contains five categories: very low (V ≤ 0.2 mm/yr), low (0.2 mm/yr < V ≤ 1.0 mm/yr), moderate (1 mm/yr < V ≤ 5 mm/yr), high (5 mm/yr < V ≤ 10 mm/yr), and very high (V > 10 mm/yr).

4.6. Taiwan

Taiwan Island is located on the subduction–collision zone between the Philippine Sea and the Eurasian plate. It is part of the Western Pacific Island arc zone and has particularly developed active faulting and very high earthquake frequency. Divided by the nearly NS-orienting Taiwan Longitudinal Valley tectonic zone, the eastern and western parts of Taiwan island are part of the Philippine and the Eurasian plates, respectively. GPS observations show that on the eastern side of the Longitudinal Valley tectonic zone, the Philippine plate moves northwestward relative to the South China continent at an average rate of 92–94 mm/yr, where it collides with the Eurasian plate and underthrusts below the Ryukyu Islands arc [109]. On the western side, the Eurasian plate underthrusts eastwards below the Taiwan island arc zone [109]. Accordingly, the Taiwan island constitutes the main active deformation zone that regulates the nearly E–W shortening between the Eurasian and Philippine plates. According to GPS observation data, the current crustal shortening rate across the entire Taiwan island is up to about 50 mm/yr, of which two-thirds (c. 40 mm/yr) have been absorbed by the Taiwan Longitudinal Valley thrust tectonic zone, while the remaining one-third (c. 20 mm/yr) has been primarily absorbed by the thrust-fold deformation zone in western Taiwan [109,110]. A review of active faults in the land area of Taiwan identified 33 or 38 known major active faults [111,112], which are distributed in three different active tectonic domains, including the longitudinal valley compressional–torsional deformation zone to the east of the Central Range, the fold-thrust deformation zone to the west of the Xueshan–Alishan mountains, and the extensional deformation zone at the northern end of the Taiwan island. The former two, which are the main regions regulating the nearly E–W compression–shortening deformation of the Taiwan island arc zone, are bounded by the nearly N–S Lishan–Chihtsu fault zone between them. Overall, the active faults in Taiwan are primarily reverse faults or reverse faults with strike-slip components, and secondarily strike-slip faults. Normal faults are found in small quantities only at the northern end of the island, which is the western extension of the Okinawa trough [113].

The Central Geological Survey of Taiwan completed an active fault review, mapping, and database-building endeavor across Taiwan in 1998 and subsequently updated the active fault data in 2000 and 2010 [111]. On its open, accessible active fault database network platform, the Central Geological Survey considered a fault as active if it “has had movement in the past 100 ka and is likely to move again in the future”, which is similar to the late Quaternary active fault term discussed above [111]. It also identified three categories of faults according to their latest movement time:

- (1)

- Category I: faults that have had movement within the past 10 ka, which are equivalent to Holocene active faults. The main indicator of these faults is displacement within the last 10 ka, the faulting of modern buildings or alluvial fans, or association with seismicity (i.e., a seismic fault), as confirmed by topographic monitoring results.

- (2)

- Category II: faults that have had movement in the past 100–10 ka, which are equivalent to late Pleistocene active faults. The main indicator of these faults is displacement within the last 100 ka or the faulting of terrace accumulation or platform accumulation.

- (3)

- Category III: “suspected active faults”, namely, faults that have had movement in the past 500 ka but whose fault activity in the last 100 ka—including the existence of faulting, the exact movement time, and the likelihood of another movement in the future—is undefinable, and are essentially similar to mid-Pleistocene active faults. The main indicator of these faults is the faulting of Quaternary rock formations or the gentle relief surface of laterite (in Taiwan, the age of this geomorphological surface approximately corresponds to the late stage of the early Pleistocene to the early stage of the mid-Pleistocene), or topographical signatures of active faulting but with no reliable evidence from geological data.

4.7. Chinese Mainland

Chinese geologists started to notice the geological-geomorphological features of active faults as early as in the 1930s–1940s, although specific active fault investigation did not commence until after the founding of the People’s Republic of China when there was an urgent need for seismic zoning and risk assessment for economic construction. At the first neotectonic movement symposium held by the Chinese Academy of Sciences in 1956, some experts mentioned that “there are still ‘active fault zones’, ‘new faults’, and ‘Quaternary faults’ that have remained active since the end of the Tertiary, especially from the Quaternary onward”. They also noted that these faults have close genetic connections to regional seismic events. Unfortunately, a precise definition of active faults was lacking at that time [114,115,116].

Later, as earthquake-related fault investigation gradually increased after the 1966 Xingtai M7.2 earthquake, China’s active fault research made a transition from qualitative analysis to quantitative measurement [117,118]. When directing the national seismic-geological endeavors, Lee (1977a, b) [119,120] repeatedly stressed the need to pay special attention to active fault zones, tectonics, and tectonic systems that have moved or are still moving, especially since Tertiary or Quaternary times. In their seismic-geological and intensity zoning of southwestern China in the 1970s, the Southwest Intensity Brigade of China Earthquake Administration (CEA) noticed that seismic faults produced by strong earthquakes are frequently found in fault zones with THE movement since the mid-Pleistocene. Accordingly, they referred to faults that had moved since the mid-Pleistocene as “moving faults” [121]. In 1980, the “Academic Symposium on Active Faults and Paleo-earthquakes in China” held by the Seismic-geological Committee of the Seismological Society of China made a comprehensive summary of the active fault research work in China in the 1970s. The event involved extensive discussions on the definition and meaning of active faults, and the use of the terms “active fault”, “moving fault”, and “seismic fault” were proposed during the event by referencing related research progress in the international world. However, the participants could not reach a consensus regarding the definitions of these structures and held that a moving fault can be either a fault “that is still moving at present or is moving now”, or “that has been moving or has been intermittently active since the Quaternary”, or “that has had some movement since the Quaternary and even the Cenozoic” [64,121,122]. Prior to the 1980s, despite the inconsistent understanding of active faults across the Chinese geological society, there was one commonly accepted view—an active fault is a fault “that has moved since the Cenozoic, the Neogene, or the Quaternary” [123], and, according to earthquake–fault correlation, earthquakes with a magnitude of 6 or larger are the most closely related to known fault activity since the Quaternary.

The active fault research and 1:50,000 mapping were specific to the Fuyun M8 earthquake fault zone, the Haiyuan fault zone, and the around-Erdos active fault zone commenced in the 1980s and greatly spurred the quantitative active fault research in China [124,125]. During this period, the definition and recognition of active faults in China were also gradually clarified. To summarize, there are three representative propositions at present:

- (1)

- The neotectonic period or the Quaternary time is emphasized as the main time limit for identifying an active fault. Under this proposition, a fault is considered active if it “has moved constantly or intermittently since the late Tertiary or the late stage of the Pliocene (primarily within the last 3.4 Ma), especially since the Quaternary, and has the potential of movement in the future” [64,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133].

- (2)

- Late Quaternary activity is emphasized. Under this proposition, a fault is considered active if it “has moved since the late Quaternary (primarily in the time span of 100–120 ka B.P.), is still moving at present, and is likely to move in the future” [11,12,118,134,135], or if there is “evidence of displacement in the late Pleistocene, especially since the Holocene” [136].

- (3)

- The initiation time of active faults may differ among different regions, and faults are active as long as they are still moving now. Accordingly, the provision of a defined and rigid upper limit of fault activity is unscientific and unnecessary. According to this proposition, a fault is considered active if it “is still moving now and is likely to move again in the future” [53,121,137]. Here, “now” is a thousand-year time scale for geological consideration equivalent to the word “present” [53]. For specific purposes, additional words related to the initiation time, such as “since the Cenozoic”, “since the late Tertiary”, “since the Quaternary”, “late Quaternary”, or “Holocene”, may be added, or, to meet the requirements of standards and operability policies, the upper time limit of fault activity may be clearly defined as appropriate for the purpose. That is, the definition of active faults may vary in the practical application according to the nature and requirements of the work performed [127]. However, considering the time scale needed for project safety assessment, the time limit for fault activity should not be too long [121]. Accordingly, an active fault can be defined as a fault “that has had movement since the late Pleistocene, namely, in the last 100 ka, especially the last 10 ka, and is still likely to move in the future [118,138].

When discussing the principles for evaluating regional crustal stability in cities, Li Xingtang proposed the concept of “engineering active fault” and described it as a fault “that has had movement in the last 50 ka and is likely to move again during the use of the project and endanger the safety of the project” [139]. He identified three criteria for an “engineering active fault”:

- (1)

- Movement since 50 ka B.P.

- (2)

- Quaternary active, with a genetic connection to deep faults, Cenozoic rifts, or grabens.

- (3)

- Deep faulting, large faulting, or Quaternary faulting with an extended length greater than 30 km.

He also suggested that important buildings in urban districts should be designed with a substantial setback distance from any active fault.

In the local, industry, and national codes and standards concerning active faults compiled by the CEA and other departments since 2000 [11,12,140], including the latest national standard for active fault detection [38], an active fault is unanimously defined as a fault “that has had movement since the late Quaternary, including Holocene active and late Pleistocene active ones”, or a fault “that has had movement within the last 120 ka”.

However, some other definitions are still being used in some of the codes and standards of the engineering construction departments. Taking the Engineering Geology Manual (Fourth Edition) as a representative, the scheme defines active faults as “faults with active traces since the Middle Pleistocene”, and proposes that active faults can be divided into three categories, namely, Holocene active faults, seismogenic faults, and non-Holocene active faults, according to the needs of engineering construction and the age of fault activity and seismogenic potential [13] (Table 7). It believes that the most significant impact on the stability of the project site is the Holocene active fault, and it is further divided into three levels “strong, medium, and weak” according to the fault activity rate and historical earthquake intensity [141] (Table 7).

Table 7.

Active fault classification schemes commonly used in the field of engineering geology in China.

The problem with this scheme, however, is that the classification is too simple and the indexes are not scientific enough. For example, it covers only strong, medium, and weak activity but fails to address the distinction between fault activity in the complex active tectonic regions in China. Also, it is obviously irrational to use the historical seismic intensity of an active fault as an indicator of fault activity, as the time scale of historically strong earthquakes is too short and can only represent the fault activity in the last thousand to hundreds of years rather than giving a full picture of the real fault activity. In reality, what really reflects fault activity is the strong earthquake recurrence interval rather than the magnitude of a strong earthquake. Moreover, many cases of earthquakes around the world have also demonstrated that faults with medium or weak activity can also lead to M > 7 strong earthquakes, such as the 2008 Wenchuan Mw7.9 earthquake [142].

5. Active Fault Standards Used in Mapping and Spatial Database Building of Active Fault

As active faults are a direct source of earthquake hazards, their mapping and database building constitute an important foundation for obtaining a panoramic view of the location and risk of these structures on a regional scale. Fault-related work is essential to achieve higher levels of active fault data and to better serve government and social needs. In fact, this fundamental geological effort is a common characteristic of countries and regions where active faults are widely present. Japan was the first to complete the systematic compilation and publication of national active fault maps in the early 1980s. The United States, Japan, Italy, New Zealand, and other countries built their respective active fault databases and made them publicly available in the early years of this century. To map active faults and spatial databases, the first step is usually to establish the definition of active faults and work out an operable scheme for classifying them since this is necessary to provide an intuitive presentation of their differences in activity and movement time and to offer a valuable reference base for users. The following subsections provide a brief outline of some of the most representative active fault classification schemes used by countries or organizations in active fault mapping and spatial database building.

5.1. Task Group II-2 Project on Major Active Faults of the World

The Scientific Committee on the Lithosphere (SCL) (formerly, the “Inter-union Commission on the Lithosphere” (ICL)) launched the International Lithosphere Program’s “Task Group II-2 Project on Major Active Faults of the World” in 1990. When leading the mapping task for the Eastern Hemisphere (the region of the Earth east of 20° W and west of 160° E (20° W–160° E), the Chairman of the Eastern Hemisphere (primarily the former Soviet Union and Europe), former Soviet Academy of Sciences geologist Trifonov and Machette (1993) [143] suggested defining active faults as faults with historical, Holocene (<10 ka), and late Pleistocene (the past 100–130 ka) manifestations of activity. For the Western Hemisphere (The region of the Earth west of 20° W and east of 160° E (160° E–20° W), primarily the American continent), Machette (2000) [23] put forward that the minimum time value for defining fault activity should at least contain 2–5 typical earthquake recurrence cycles. He highlighted the distinctions in a geodynamic setting among different parts of the world can lead to remarkable differences in fault activity, especially with respect to the earthquake recurrence interval, which can span from tens of years to more than a hundred thousand years. Therefore, active faults must be defined according to the tectonic movement in the particular area in question, instead of setting a uniform minimum time value for fault activity.

In addition to assigning the definition of active faults and the principles thereof, the project design also included two uniform sets of active fault classification schemes that depicted the last activation time and slip rate (V) of faults [23,143,144] (Table 8). According to the last activation time, faults were divided into five categories. According to their slip rate, they are divided into three categories. These schemes were modified for both the Eastern and Western Hemispheres in subsequent implementation due to the divergences in the guiding ideology and the limited availability of quantitative data.

Table 8.

The classification scheme of active faults developed by the International Lithosphere Program’s “Task Group II-2 Project on Major Active Faults of the World”.

In the Western Hemisphere, although a five-category scheme depicting the movement time of active faults was adopted, different time intervals were used for different types of faults [23,145], and the slip-rate classification scheme was proposed to be extended to four categories (Table 8). It was also noticed that class I faults are mostly found in plate boundary zones, class III and IV faults are primarily intraplate faults, and class II faults are found in both types of regions. In practice, however, the original 3-category slip rate classification scheme was still adopted for many countries and regions due to the lack of sufficient quantitative data on fault activity [146,147,148]. Later, the schemes for the Western Hemisphere were also borrowed into the “Map and Data for Quaternary Faults and Fault Systems of the Nation” project, especially the time-specific scheme, as was demonstrated in the guidelines for evaluating surface-fault-rupture hazards in Hawaii and Utah [76,149].

In the Eastern Hemisphere, due to the non-availability of sufficient data on fault movement time, the original slip-rate classification scheme of five categories was simplified into a three-category regime and was retained [144] (Table 8).

The mapping guidelines and active fault classification schemes established by this project offered very valuable reference or guidance for the active fault mapping endeavors of some countries and regions that followed.

5.2. The Global Neotectonic Fault Database under the GEM Faulted Earth Project

One fundamental task of the GEM Faulted Earth (GFE) project, an initiative that aimed to build a global seismic hazard evaluation model, was to build a “Global Neotectonic Fault Database” with the joint efforts of several countries or organizations. The database is practically constructed based on the DISS. For this purpose, detailed active fault classification schemes were established based on three important quantitative criteria that best describe the seismogenic potential and future movement risk of faults: the last activation time of the fault, the average recurrence interval (or recurrence interval of strong earthquakes) (I), and the average slip rate (V) [150].

As the neotectonic faults covered in this database involve many different types of faults of varying activity levels, to better discriminate fault activity among different regions, each of the three classification schemes included 6–9 categories or levels of active faults (Table 9). Among them, the age classification of fault activity includes 6 categories (I~IV). It is believed that the time limit of a neotectonic fault should be at least 10 Ma on a global scale, and the time limit of a historical active fault can be determined according to the starting time of historical records of different countries. That means this scheme should be applied flexibly. If the neotectonic fault in a region has been formed in the last 0.5 Ma, it is not necessary to consider the fault active before 0.5 Ma. Under the scheme depicting the average recurrence interval, faults are divided into nine levels (I–IX), and it is suggested that the corresponding fault slip rate can be estimated by assuming that the recurrence interval of faults approximately represents the time required for faults to accumulate 1 m surface dislocation, and based on this, faults can be further divided into 8 levels (I–VIII) according to the average slip rate (Table 9). In addition, there is usually a close relationship between the last activation time, slip rate, and average recurrence interval of faults. It is noted that the last activation time, slip rate, and average recurrence interval are closely connected with one other—for a high slip-rate fault, its average recurrence interval is usually shorter and the elapsed time of the latest active is generally shorter, too—yet they do not precisely correspond to one another, at least when it concerns intraplate faults, which are often found to form clusters.

Table 9.

The classification scheme of active fault adopted by GEM “Global Neotectonic Fault Database”.

5.3. The “U.S. Quaternary Fault and Fold Database” Project

To obtain a comprehensive understanding of the distribution and Quaternary activity of active faults that pose a potential risk of geological hazards, the USGS carried out a “U.S. Quaternary Fault and Database” project from 1993 to 2003. A renewable database of known and suspected faults containing geologic, geomorphic, and geographic information was built in a uniform format for faults and parameters [35,151]. In 2004, the “U.S. Quaternary Fault and Fold Database” covering nearly 2000 active faults and their data was published on the USGS website platform for free access by the public. This allowed the general public to know the active faults in their area, how they are distributed, where their exact locations were when the last earthquake occurred, and what the directions and slip rates of the faults are.

The U.S. Quaternary Fault and Fold Database mainly involved the classification of fault activity with respect to movement time and spatial accuracy. It drew inspiration from the classification scheme used by the “Project on Major Active Faults of the World” for the Western Hemisphere led by the United States, considering six categories (Table 10): Historical (<150 years), Late Pleistocene to Holocene (<15,000 years), Late Quaternary (<130,000 years), Middle and Late Quaternary (<750,000 years), Quaternary (undivided) (<2.6 million years), and uncertain time, which are shown by different colors on the map. The database also considered “well-defined, moderately defined, and suspected” faults, which are shown by solid lines, broken lines, and dotted lines on the map [152].

Table 10.

The representative age classification scheme for active faults.

5.4. The Euro–Mediterranean Database of Seismogenic Faults (EDSF)

When implementing its “2013 European Seismic Hazard Model” (ESHM13) project, the European Union designed a “Seismic Hazard Harmonization in Europe” (SHARE, 2009–2013) project and set up a separate task group for the European Database of Active Faults and Seismogenic Sources, to compile the “Euro–Mediterranean Database of Seismogenic Faults” (EDSF) and maps [47]. In this database and the associated maps, the European continent and the adjacent seas are divided into six seismotectonic regions [46,47]: Stable continental region, oceanic crustal region, active shallow crustal region, subduction zone, subduction-free deep-source seismic region, and active volcano or geothermal region. A total of 1128 active faults have been compiled and grouped into seven levels by slip rate in roughly the same manner as in the GEM “Global Neotectonic Fault Database” project [46,47], but with a different set of slip rate values (Table 11).

Table 11.

The active fault classification scheme of the European Union “in Europe-the Mediterranean seismogenic fault database”.

5.5. Japan’s Active Fault Mapping

Japan’s Research Group for Active Faults mapped inland active faults nationwide from 1975 to 1990. It was also the first to develop a set of classification schemes based on the degree of accuracy of active fault identification and the intensity of fault movement (or “activity”, as described by the average slip rate). The degree of accuracy criterion depicted three categories of active faults [78,79] (Table 12), emphasizing that whether Category II and III faults are active faults should be confirmed through further field investigation and detailed study. The classification of fault activity includes five levels of gradually decreasing fault rate: AA, A, B, C, and D (Table 12). However, in the later active fault mapping, it is considered that there is no AA-level fault in the Japanese land area, while the D-level fault may exist, but its activity is too weak to identify. Therefore, the compilation group of the 1: 2,000,000 active faults maps of Japan has appropriately simplified the early scheme in the newly compiled “1:2,000,000 active fault map of the Japanese archipelago” [84]. In this map, the accuracy criterion depicts two categories—I and II, and the activity criterion depicts three levels—A (V ≥ 1.0 mm/yr), B (0.1 mm/yr ≤ V < 1 mm/yr), and C (V ≤ 0.1 mm/yr). Among them, Levels A and B are recommended as active faults to focus on disaster prevention.

Table 12.