Examining How Dog ‘Acquisition’ Affects Physical Activity and Psychosocial Well-Being: Findings from the BuddyStudy Pilot Trial

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

2.2. Community Partner

2.3. Study Design

2.4. Procedures

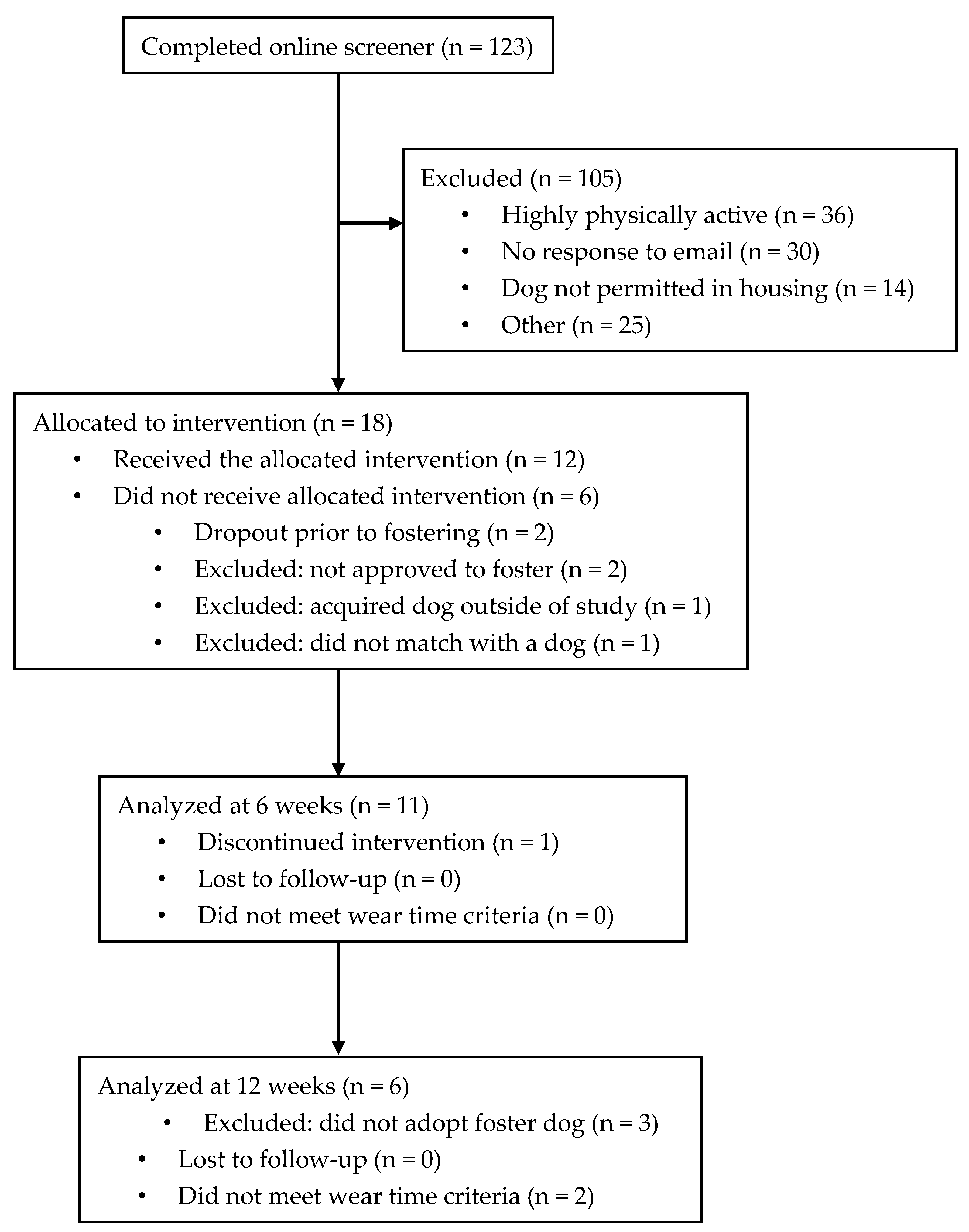

2.4.1. Screening Procedures

2.4.2. Foster Procedures

2.5. Measures

2.5.1. Feasibility

2.5.2. Device-Measured PA and Sedentary Behavior

2.5.3. Self-Reported Dog Walking

2.5.4. Psychosocial Outcomes

2.6. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Feasibility

3.2. Participant Characteristics

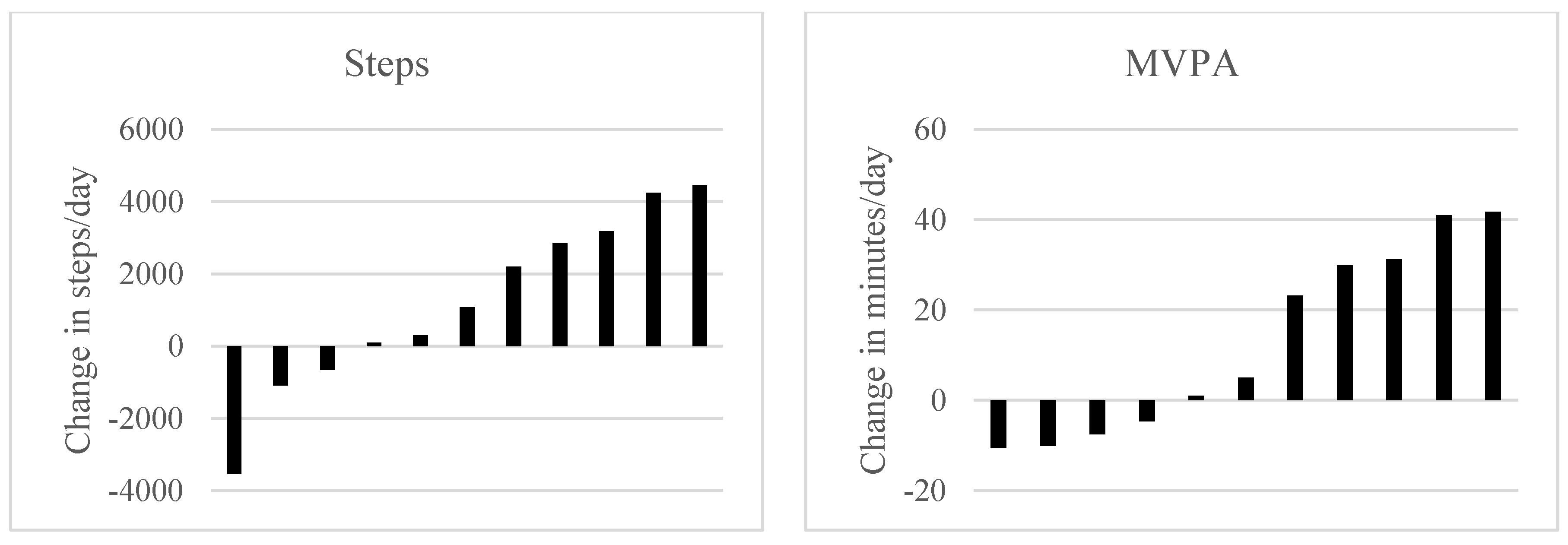

3.3. PA and Sedentary Behavior

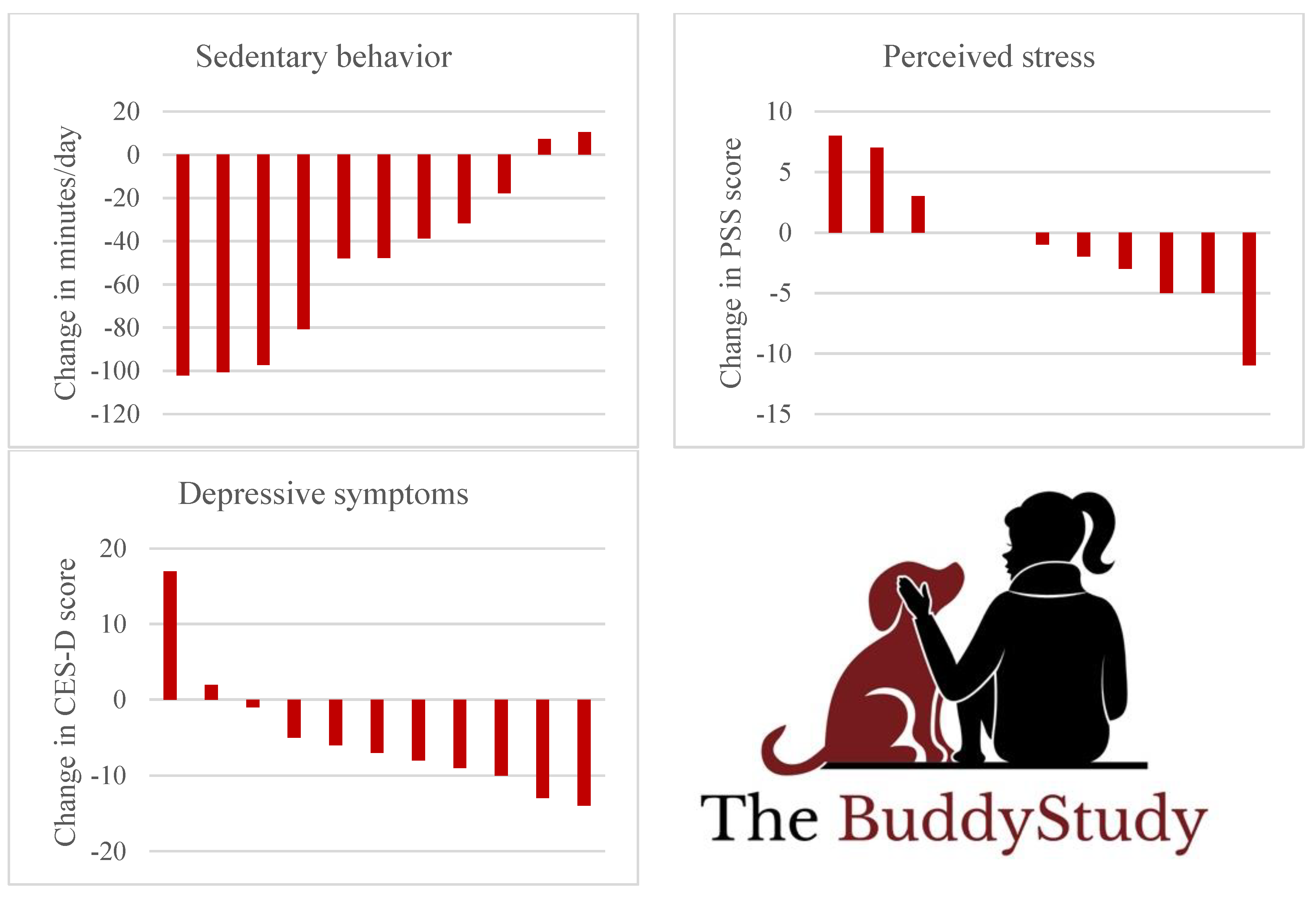

3.4. Psychosocial Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Scientific Report; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; p. 779.

- Powell, K.E.; King, A.C.; Buchner, D.M.; Campbell, W.W.; DiPietro, L.; Erickson, K.I.; Hillman, C.H.; Jakicic, J.M.; Janz, K.F.; Katzmarzyk, P.T. The Scientific Foundation for the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, 2nd Edition. J. Phys. Act. Health 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackwell, D.L.; Clarke, T.C. State Variation in Meeting the 2008 Federal Guidelines for Both Aerobic and Muscle-strengthening Activities Through Leisure-time Physical Activity Among Adults Aged 18–64: United States, 2010–2015. Natl. Health Stat. Rep. 2018, 112, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Christian, H.E.; Westgarth, C.; Bauman, A.; Richards, E.A.; Rhodes, R.E.; Evenson, K.R.; Mayer, J.A.; Thorpe, R.J. Dog ownership and physical activity: A review of the evidence. J. Phys. Act. Health 2013, 10, 750–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soares, J.; Epping, J.N.; Owens, C.J.; Brown, D.R.; Lankford, T.J.; Simoes, E.J.; Caspersen, C.J. Odds of Getting Adequate Physical Activity by Dog Walking. J. Phys. Act. Health 2015, 12 (Suppl. 1), S102–S109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dunn, S.L.; Sit, M.; DeVon, H.A.; Makidon, D.; Tintle, N.L. Dog Ownership and Dog Walking: The Relationship with Exercise, Depression, and Hopelessness in Patients with Ischemic Heart Disease. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2018, 33, E7–E14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riske, J.; Janert, M.; Kahle-Stephan, M.; Nauck, M.A. Owning a Dog as a Determinant of Physical Activity and Metabolic Control in Patients with Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cutt, H.E.; Knuiman, M.W.; Giles-Corti, B. Does getting a dog increase recreational walking? Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2008, 5, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serpell, J. Beneficial effects of pet ownership on some aspects of human health and behaviour. J. R. Soc. Med. 1991, 84, 717–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, J.; Parast, L.; Babey, S.H.; Miles, J.V. Exploring the differences between pet and non-pet owners: Implications for human-animal interaction research and policy. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0179494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donoghue, G.; Kennedy, A.; Puggina, A.; Aleksovska, K.; Buck, C.; Burns, C.; Cardon, G.; Carlin, A.; Ciarapica, D.; Colotto, M.; et al. Socio-economic determinants of physical activity across the life course: A “DEterminants of DIet and Physical ACtivity” (DEDIPAC) umbrella literature review. PLoS ONE 2018, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, K.; Barton, L.; Darling, M.; Antao, V.; Kim, F.A.; Monavvari, A. Pets’ Impact on Your Patients’ Health: Leveraging Benefits and Mitigating Risk. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2015, 28, 526–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Laan, M.J.; Rose, S. Targeted Learning: Causal Inference for Observational and Experimental Data; Springer Series in Statistics; Springer-Verlag: New York, NY, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-1-4419-9781-4. [Google Scholar]

- Taubman, S.L.; Robins, J.M.; Mittleman, M.A.; Hernán, M.A. Intervening on risk factors for coronary heart disease: An application of the parametric g-formula. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2009, 38, 1599–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernán, M.A.; Lanoy, E.; Costagliola, D.; Robins, J.M. Comparison of dynamic treatment regimes via inverse probability weighting. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2006, 98, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robins, J. A new approach to causal inference in mortality studies with a sustained exposure period—application to control of the healthy worker survivor effect. Appl. Math. Model 1986, 7, 1393–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, K.; Shykoff, B.E.; Izzo, J.L., Jr. Pet Ownership, but Not ACE Inhibitor Therapy, Blunts Home Blood Pressure Responses to Mental Stress. Hypertension 2001, 38, 815–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lyden, K.; Keadle, S.K.; Staudenmayer, J.; Freedson, P.S. A method to estimate free-living active and sedentary behavior from an accelerometer. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2014, 46, 386–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aadland, E.; Ylvisåker, E. Reliability of the Actigraph GT3X+ Accelerometer in Adults under Free-Living Conditions. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0134606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedson, P.S.; Melanson, E.; Sirard, J. Calibration of the Computer Science and Applications, Inc. accelerometer. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1998, 30, 777–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, E.A.; McDonough, M.H.; Edwards, N.E.; Lyle, R.M.; Troped, P.J. Development and psychometric testing of the Dogs and WalkinG Survey (DAWGS). Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2013, 84, 492–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. A global measure of perceived stress. JHSB 1983, 24, 385–396. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E.-H. Review of the psychometric evidence of the perceived stress scale. Asian Nurs. Res. 2012, 6, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Janicki-Deverts, D. Who’s stressed? Distributions of psychological stress in the United States in probability samples from 1983, 2006, and 2009. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 42, 1320–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radloff, L.S. The CES-D Scale: A Self-Report Depression Scale for Research in the General Population. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1977, 1, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, L.; Martin, K.; Christian, H.; Nathan, A.; Lauritsen, C.; Houghton, S.; Kawachi, I.; McCune, S. The Pet Factor—Companion Animals as a Conduit for Getting to Know People, Friendship Formation and Social Support. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0122085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraus, W.E.; Yates, T.; Tuomilehto, J.; Sun, J.-L.; Thomas, L.; McMurray, J.J.V.; Bethel, M.A.; Holman, R.R. Relationship between baseline physical activity assessed by pedometer count and new-onset diabetes in the NAVIGATOR trial. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 2018, 6, e000523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yates, T.; Haffner, S.M.; Schulte, P.J.; Thomas, L.; Huffman, K.M.; Bales, C.W.; Califf, R.M.; Holman, R.R.; McMurray, J.J.V.; Bethel, M.A.; et al. Association between change in daily ambulatory activity and cardiovascular events in people with impaired glucose tolerance (NAVIGATOR trial): A cohort analysis. Lancet 2014, 383, 1059–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jefferis, B.J.; Parsons, T.J.; Sartini, C.; Ash, S.; Lennon, L.T.; Papacosta, O.; Morris, R.W.; Wannamethee, S.G.; Lee, I.-M.; Whincup, P.H. Does total volume of physical activity matter more than pattern for onset of CVD? A prospective cohort study of older British men. Int. J. Cardiol. 2019, 278, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, T.; Pezic, A.; Sun, C.; Cochrane, J.; Venn, A.; Srikanth, V.; Jones, G.; Shook, R.P.; Shook, R.; Sui, X.; et al. Objectively Measured Daily Steps and Subsequent Long Term All-Cause Mortality: The Tasped Prospective Cohort Study. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0141274. [Google Scholar]

- Jefferis, B.J.; Parsons, T.J.; Sartini, C.; Ash, S.; Lennon, L.T.; Papacosta, O.; Morris, R.W.; Wannamethee, S.G.; Lee, I.-M.; Whincup, P.H. Objectively measured physical activity, sedentary behaviour and all-cause mortality in older men: Does volume of activity matter more than pattern of accumulation? Br. J. Sports Med. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.-M.; Shiroma, E.J.; Kamada, M.; Bassett, D.R.; Matthews, C.E.; Buring, J.E. Association of Step Volume and Intensity With All-Cause Mortality in Older Women. JAMA Intern Med. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, E.A.; Troped, P.J.; Lim, E. Assessing the Intensity of Dog Walking and Impact on Overall Physical Activity: A Pilot Study Using Accelerometry. Open J. Prev. Med. 2014, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, D.R.; Hivert, M.-F.; Alhassan, S.; Camhi, S.M.; Ferguson, J.F.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Lewis, C.E.; Owen, N.; Perry, C.K.; Siddique, J.; et al. Sedentary Behavior and Cardiovascular Morbidity and Mortality: A Science Advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2016, 134, e262–e279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australia’s Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour Guidelines and the Australian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines. Available online: https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/health-pubhlth-strateg-phys-act-guidelines (accessed on 6 September 2019).

- Garcia, D.O.; Wertheim, B.C.; Manson, J.E.; Chlebowski, R.T.; Volpe, S.L.; Howard, B.V.; Stefanick, M.L.; Thomson, C.A. Relationships between dog ownership and physical activity in postmenopausal women. Prev. Med. 2015, 70, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, M.N.; King, A.C.; Sallis, J.F.; Frank, L.D.; Saelens, B.E.; Conway, T.L.; Cain, K.L.; Kerr, J. Caregiving, Transport-Related, and Demographic Correlates of Sedentary Behavior in Older Adults: The Senior Neighborhood Quality of Life Study. JAH 2016, 28, 812–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dall, P.M.; Ellis, S.L.H.; Ellis, B.M.; Grant, P.M.; Colyer, A.; Gee, N.R.; Granat, M.H.; Mills, D.S. The influence of dog ownership on objective measures of free-living physical activity and sedentary behaviour in community-dwelling older adults: A longitudinal case-controlled study. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holt-Lunstad, J.; Smith, T.B.; Layton, J.B. Social relationships and mortality risk: A meta-analytic review. PLoS Med. 2010, 7, e1000316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holt-Lunstad, J.; Smith, T.B.; Baker, M.; Harris, T.; Stephenson, D. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: A meta-analytic review. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 10, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westgarth, C.; Christley, R.M.; Christian, H.E. How might we increase physical activity through dog walking?: A comprehensive review of dog walking correlates. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2014, 11, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pets by the Numbers. Available online: https://www.animalsheltering.org/page/pets-by-the-numbers (accessed on 13 January 2019).

- Neumann, S.L. Animal Welfare Volunteers: Who Are They and Why Do They Do What They Do? Anthrozoös 2010, 23, 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, D.; Lawson, K.D.; Kolbe-Alexander, T.L.; Finkelstein, E.A.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; van Mechelen, W.; Pratt, M. Lancet Physical Activity Series 2 Executive Committee The economic burden of physical inactivity: A global analysis of major non-communicable diseases. Lancet 2016, 388, 1311–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Outcome | Baseline (n = 11) 1 | Week 6 (n = 11) | Week 12 (n = 8)2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Device-measured PA | |||

| Daily steps | 6976.6 ± 2532.0 | 8168.7 ± 3827.8 | 7528.1 ± 4356.93 |

| MVPA minutes per day | 35.3 ± 19.7 | 48.0 ± 33.6 | 37.8 ± 32.23 |

| Sedentary minutes per day | 574.0 ± 65.3 | 524.3 ± 68.3 | 512.3 ± 94.33 |

| Self-reported dog walking | |||

| Days w/ at least 1 walk | - | 6.5 ± 0.9 | 6.8 ± 0.5 |

| Minutes per typical walk | - | 23.0 ± 16.8 | 18.1 ± 17.3 |

| Minutes of dog walking per week | - | 340.3 ± 243.7 | 242.5 ± 196.1 |

| Depressive symptoms (CES-D; scale range 0–60) | 14.4 ± 13.0 | 9.5 ± 10.0 | 7.9 ± 8.9 |

| Perceived stress (PSS; score range 0–40) | 15.6 ± 6.9 | 14.7 ± 5.8 | 10.0 ± 7.4 |

| Social facilitation | |||

| n (%) met person in neighborhood through foster dog | - | 6 (55%) | - |

| n (%) consider person met through foster dog to be a friend | - | 1 (9%) | - |

| n (%) received social support from person met through foster dog | - | 5 (45%) | - |

| Question/Prompt | N Endorsing 1 | Exemplary Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| “What has been the best thing about fostering a dog?” | ||

| Fun/happiness/joy | 5 | “My pup is a continuous source of happiness in my life - coming home is much more enjoyable than it ever has been. To know she is always at home waiting for me gives me a sense of joy and comfort.” |

| Companionship | 3 | “The continuous love and kisses and snuggles! He is a constant companion that always cheers me up.” |

| Family bonding | 3 | “The best thing about fostering X has been our family working together to care for him.” |

| “What has been the most challenging thing about fostering a dog?” | ||

| Stress/responsibility | 4 | “In a busy household, I already feel like I have a pile of people to care for, be available for, keep healthy, feed, etc. Adding another one can sometimes feel overwhelming (especially when she wasn’t feeling well)…” “The learning curve of understanding my foster dogs needs and how to juggle that with my own needs has been tricky at times.” |

| “Please write a brief reflection on how fostering a dog has affected your quality of life.” | ||

| Improved quality of life | 5 | “It’s improved my quality of life. He’s brought a lot of joy into my life, and I think I’m less stressed since he’s around.” “Fostering has provided me with a happier and healthier lifestyle. Coming home to a pup that is excited to see you is the best feeling. Fostering has also encouraged me to go on many more walks and seek a more active lifestyle.” |

| Mixed impact on quality of life | 3 | “It has been overwhelming, exciting, stressful, relaxing, wonderful and difficult.” “It has been very mixed. I have been happy to have his company, and gratified to help him learn, but it has been very difficult to do anything but take care of him for the last six weeks…” |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Potter, K.; Teng, J.E.; Masteller, B.; Rajala, C.; Balzer, L.B. Examining How Dog ‘Acquisition’ Affects Physical Activity and Psychosocial Well-Being: Findings from the BuddyStudy Pilot Trial. Animals 2019, 9, 666. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani9090666

Potter K, Teng JE, Masteller B, Rajala C, Balzer LB. Examining How Dog ‘Acquisition’ Affects Physical Activity and Psychosocial Well-Being: Findings from the BuddyStudy Pilot Trial. Animals. 2019; 9(9):666. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani9090666

Chicago/Turabian StylePotter, Katie, Jessica E. Teng, Brittany Masteller, Caitlin Rajala, and Laura B. Balzer. 2019. "Examining How Dog ‘Acquisition’ Affects Physical Activity and Psychosocial Well-Being: Findings from the BuddyStudy Pilot Trial" Animals 9, no. 9: 666. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani9090666

APA StylePotter, K., Teng, J. E., Masteller, B., Rajala, C., & Balzer, L. B. (2019). Examining How Dog ‘Acquisition’ Affects Physical Activity and Psychosocial Well-Being: Findings from the BuddyStudy Pilot Trial. Animals, 9(9), 666. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani9090666