The Role of Chitosan as a Possible Agent for Enteric Methane Mitigation in Ruminants

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

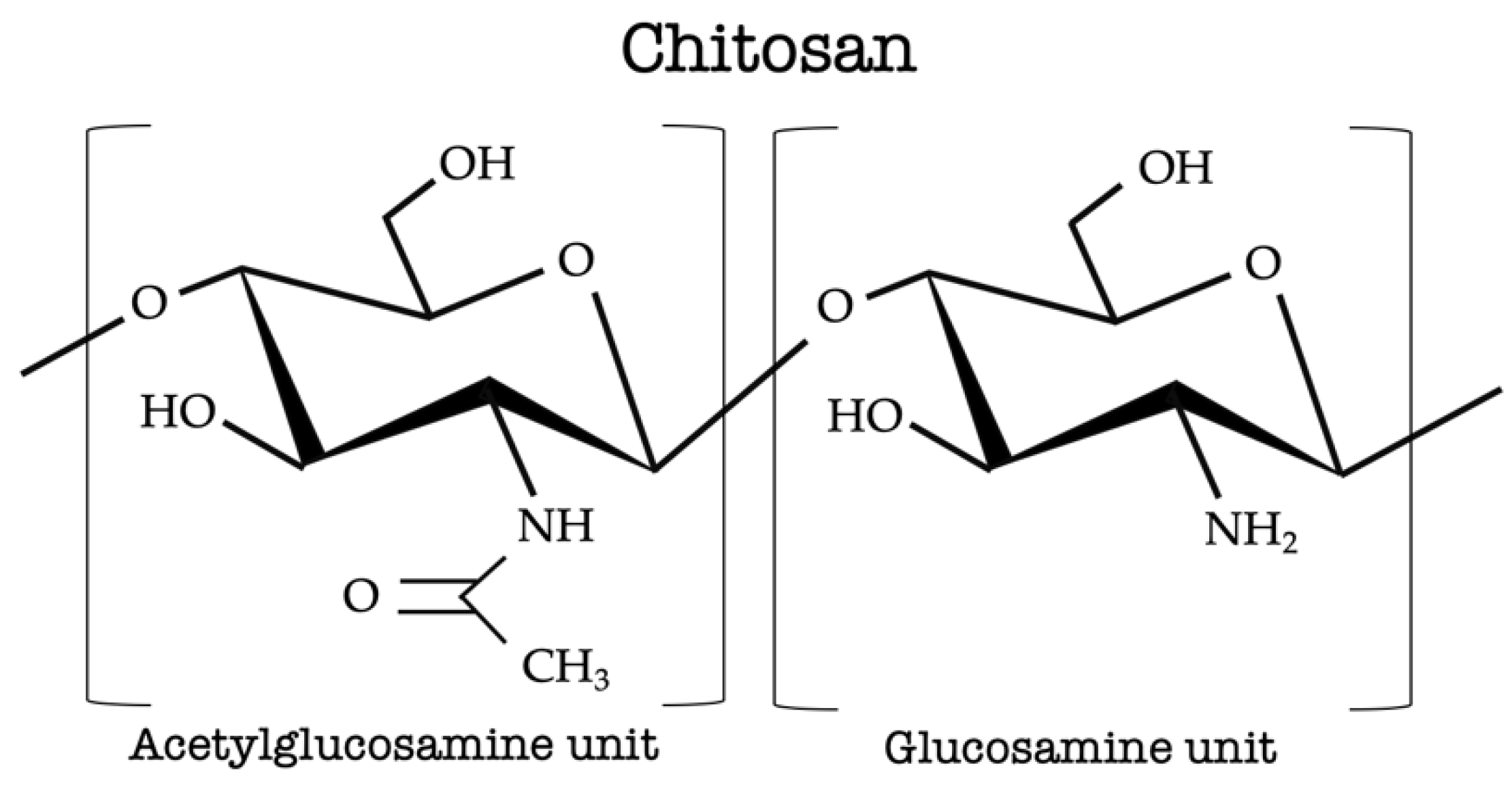

2. Chitosan

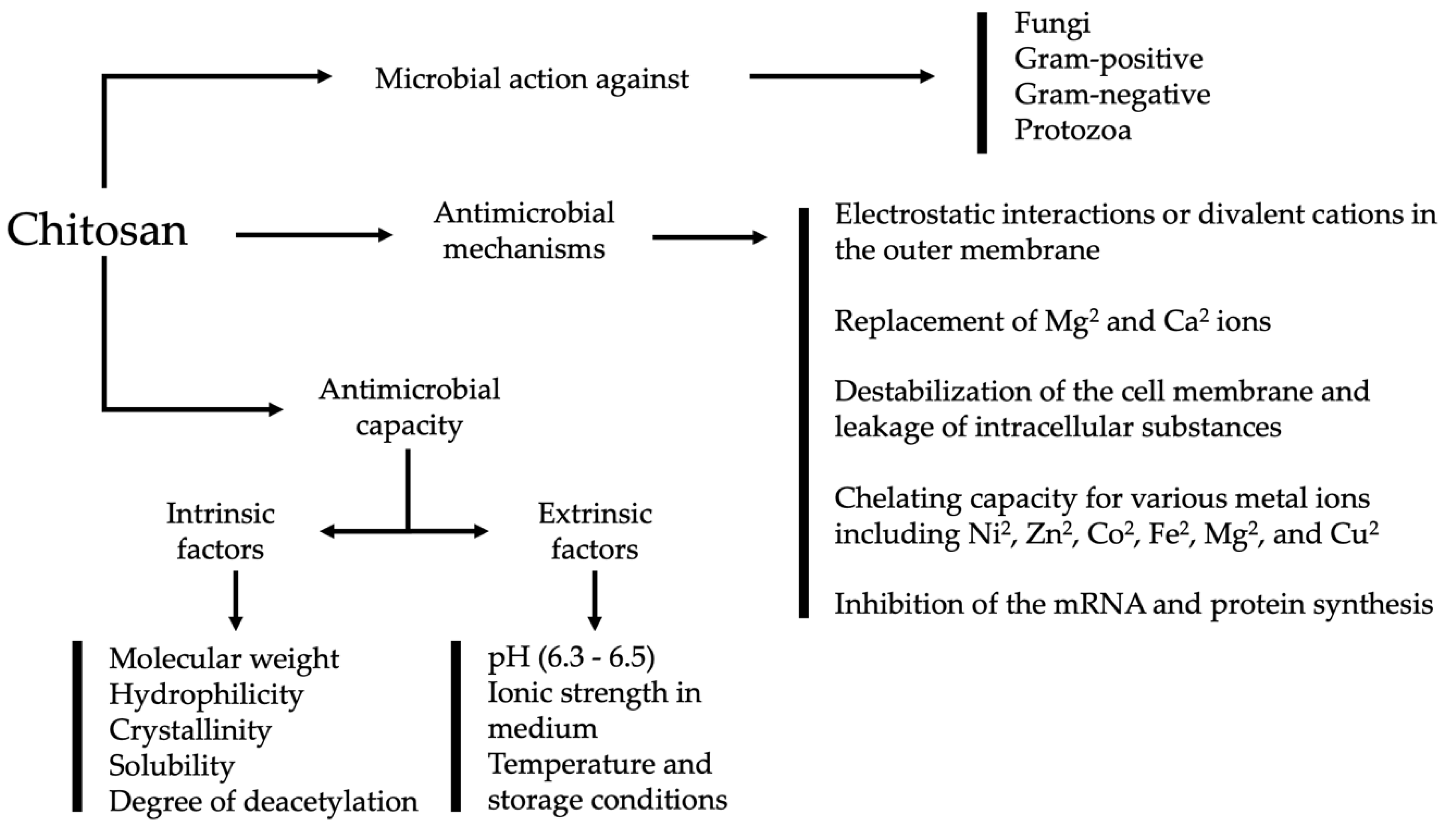

3. Antimicrobial Mechanism

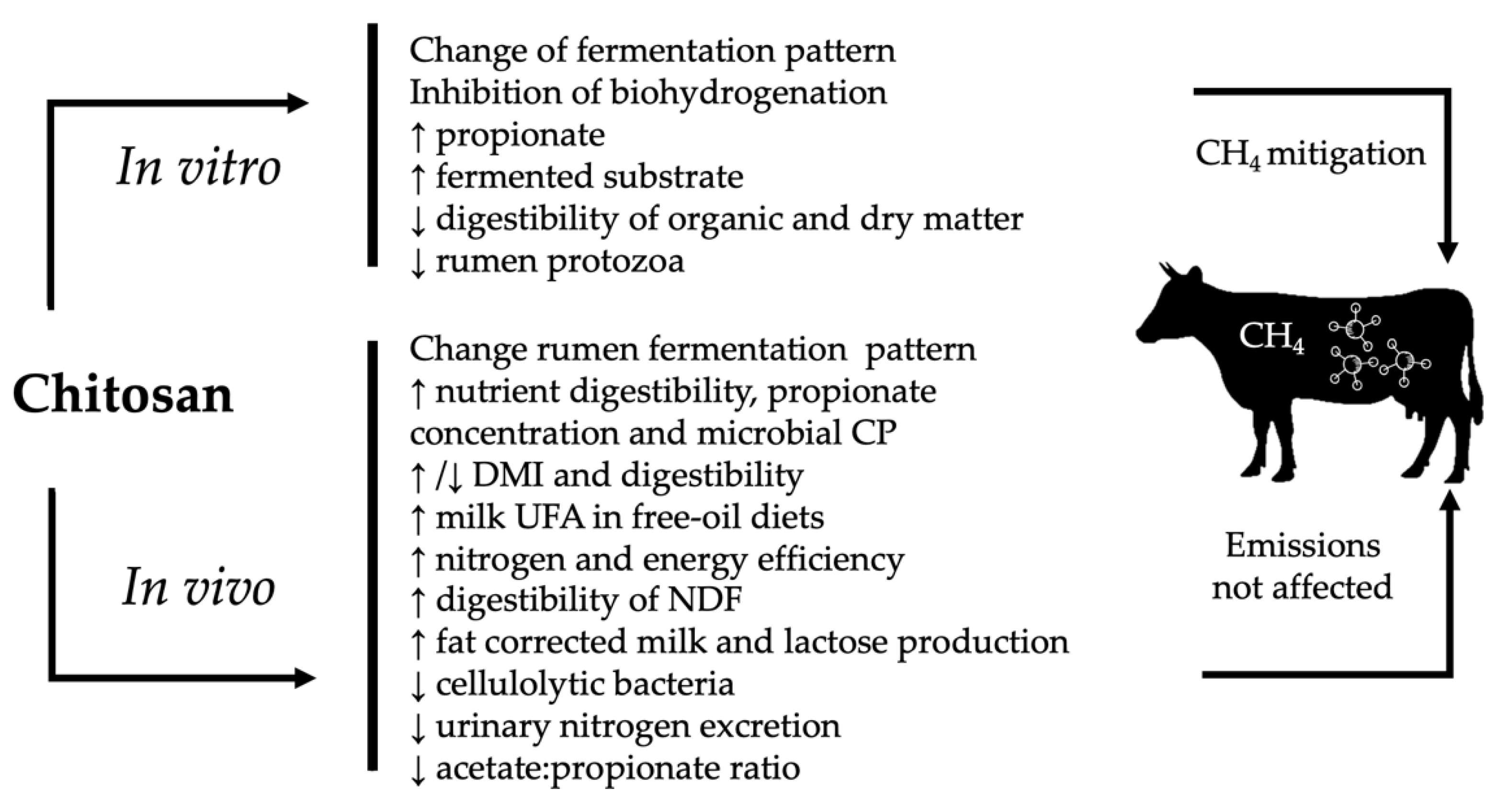

4. Effects of Chitosan in in Vitro Experiments

5. Effects of Chitosan in In Vivo Experiments

5.1. Dry Matter Intake

5.2. Rumen Fermentation Pattern

5.3. Rumen Microbial Population

5.4. Enteric Methane Emissions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Benchaar, C.; Greathead, H. Essential oils and opportunities to mitigate enteric methane emissions from ruminants. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2011, 166–167, 338–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassey, K.R. Livestock methane emission and its perspective in the global methane cycle. Aust. J. Exp. Agric. 2008, 48, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K.A.; Johnson, D.E. Methane emissions from cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 1995, 73, 2483–2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, J.; McSweeney, C.; Wright, A.-D.G.; Bishop-Hurley, G.; Kalantar-zadeh, K. Measuring Methane Production from Ruminants. Trends Biotechnol. 2016, 34, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirzaei-Aghsaghali, A.; Maheri-Sis, N. Factors affecting mitigation of methane emission from ruminants: Microbiology and biotechnology strategies. J. Anim. Behav. Biometeorol. 2015, 4, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, J. Prophylactic Modulation of Methane and Nitrous Oxide Emitted from Ruminants Livestock for Sustainable Animal Agriculture. Media Peternak. 2014, 37, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebreab, E.; Clark, K.; Wagner-Riddle, C.; France, J. Methane and nitrous oxide emissions from Canadian animal agriculture: A review. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 2006, 86, 135–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottle, D.J.; Nolan, J.V.; Wiedemann, S.G. Ruminant enteric methane mitigation: A review. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2011, 51, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, K.J.; Crompton, L.A.; Bannink, A.; Dijkstra, J.; Yáñez-Ruiz, D.R.; O’Kiely, P.; Kebreab, E.; Eugène, M.A.; Yu, Z.; Shingfield, K.J.; et al. Review of current in vivo measurement techniques for quantifying enteric methane emission from ruminants. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2016, 219, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broucek, J. Options to methane production abatement in ruminants: A review. J. Anim. Plant Sci. 2018, 28, 348–364. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, J.; Tan, Z.; Wang, M. Potential and existing mechanisms of enteric methane production in ruminants. Sci. Agric. 2014, 71, 430–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hristov, A.N.; Oh, J.; Firkins, J.L.; Dijkstra, J.; Kebreab, E.; Waghorn, G.; Makkar, H.P.S.; Adesogan, A.T.; Yang, W.; Lee, C.; et al. SPECIAL TOPICS—Mitigation of methane and nitrous oxide emissions from animal operations: I. A review of enteric methane mitigation options1. J. Anim. Sci. 2013, 91, 5045–5069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, E.T.; Kim, C.-H.; Min, K.-S.; Lee, S.S. Effects of Plant Extracts on Microbial Population, Methane Emission and Ruminal Fermentation Characteristics in In vitro. Asian Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2012, 25, 806–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patra, A.K. The effect of dietary fats on methane emissions, and its other effects on digestibility, rumen fermentation and lactation performance in cattle: A meta-analysis. Livest. Sci. 2013, 155, 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapp, J.R.; Laur, G.L.; Vadas, P.A.; Weiss, W.P.; Tricarico, J.M. Invited review: Enteric methane in dairy cattle production: Quantifying the opportunities and impact of reducing emissions. J. Dairy Sci. 2014, 97, 3231–3261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrduljaš, N.; Krešić, G.; Bilušić, T. Polyphenols: Food Sources and Health Benefits. In Functional Food—Improve Health through Adequate Food; Hueda, M.C., Ed.; InTech: London, UK, 2017; ISBN 978-953-51-3439-8. [Google Scholar]

- Roque, B.M.; Salwen, J.K.; Kinley, R.; Kebreab, E. Inclusion of Asparagopsis armata in lactating dairy cows’ diet reduces enteric methane emission by over 50 percent. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 234, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, R.J.; Rooke, J.A.; Duthie, C.-A.; Hyslop, J.J.; Ross, D.W.; McKain, N.; de Souza, S.M.; Snelling, T.J.; Waterhouse, A.; Roehe, R. Archaeal abundance in post-mortem ruminal digesta may help predict methane emissions from beef cattle. Sci. Rep. 2015, 4, 5892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodas, R.; López, S.; Fernández, M.; García-González, R.; Rodríguez, A.B.; Wallace, R.J.; González, J.S. In vitro screening of the potential of numerous plant species as antimethanogenic feed additives for ruminants. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2008, 145, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, A.K.; Kamra, D.N.; Bhar, R.; Kumar, R.; Agarwal, N. Effect of Terminalia chebula and Allium sativum on in vivo methane emission by sheep: Methane inhibition in sheep by plant feed additives. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2011, 95, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akula, R.; Ravishankar, G.A. Influence of abiotic stress signals on secondary metabolites in plants. Plant Signal. Behav. 2011, 6, 1720–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, A.K.; Saxena, J. A new perspective on the use of plant secondary metabolites to inhibit methanogenesis in the rumen. Phytochemistry 2010, 71, 1198–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Gastelen, S.; Dijkstra, J.; Bannink, A. Are dietary strategies to mitigate enteric methane emission equally effective across dairy cattle, beef cattle, and sheep? J. Dairy Sci. 2019, 102, 6109–6130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klevenhusen, F.; Zeitz, J.O.; Duval, S.; Kreuzer, M.; Soliva, C.R. Garlic oil and its principal component diallyl disulfide fail to mitigate methane, but improve digestibility in sheep. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2011, 166–167, 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, D.; Tomar, S.K.; Sirohi, S.K.; Kumar, V.; Kumar, M. Efficacy of different essential oils in modulating rumen fermentation in vitro using buffalo rumen liquor. Vet. World 2014, 7, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Montoya, J.; De Campeneere, S.; Van Ranst, G.; Fievez, V. Interactions between methane mitigation additives and basal substrates on in vitro methane and VFA production. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2012, 176, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Valle, T.A.; de Paiva, P.G.; de Jesus, E.F.; de Almeida, G.F.; Zanferari, F.; Costa, A.G.B.V.B.; Bueno, I.C.S.; Rennó, F.P. Dietary chitosan improves nitrogen use and feed conversion in diets for mid-lactation dairy cows. Livest. Sci. 2017, 201, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, A.O.C.; Goes, R.H.T.B.; Gandra, J.R.; Takiya, C.S.; Branco, A.F.; Jacaúna, A.G.; Oliveira, R.T.; Souza, C.J.S.; Vaz, M.S.M. Increasing doses of chitosan to grazing beef steers: Nutrient intake and digestibility, ruminal fermentation, and nitrogen utilization. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2017, 225, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Paiva, P.G.; de Jesus, E.F.; Del Valle, T.A.; de Almeida, G.F.; Costa, A.G.B.V.B.; Consentini, C.E.C.; Zanferari, F.; Takiya, C.S.; da Silva Bueno, I.C.; Rennó, F.P. Effects of chitosan on ruminal fermentation, nutrient digestibility, and milk yield and composition of dairy cows. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2017, 57, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Cai, C.; Li, J.; Li, J.; Li, J.; Sun, T.; Wang, L.; Wu, H.; Yu, G. Chitosan-Based Nanomaterials for Drug Delivery. Molecules 2018, 23, 2661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, W.L.; Khor, E.; Tan, T.K.; Lim, L.Y.; Tan, S.C. Concurrent production of chitin from shrimp shells and fungi. Carbohydr. Res. 2001, 332, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Kadib, A. Metal-Polysaccharide Interplay: Beyond Metal Immobilization, Graphenization-Induced-Anisotropic Growth. ChemSusChem 2016, 9, 238–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duffy, C.; O’Riordan, D.; O’Sullivan, M.; Jacquier, J.-C. In vitro evaluation of chitosan copper chelate gels as a multimicronutrient feed additive for cattle. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 98, 4177–4183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Divya, K.; Vijayan, S.; George, T.K.; Jisha, M.S. Antimicrobial properties of chitosan nanoparticles: Mode of action and factors affecting activity. Fibers Polym. 2017, 18, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muxika, A.; Etxabide, A.; Uranga, J.; Guerrero, P.; de la Caba, K. Chitosan as a bioactive polymer: Processing, properties and applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 105, 1358–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Knidri, H.; Belaabed, R.; Addaou, A.; Laajeb, A.; Lahsini, A. Extraction, chemical modification and characterization of chitin and chitosan. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 120, 1181–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandra, J.R.; Takiya, C.S.; Oliveira, E.R.D.; Paiva, P.G.D.; Goes, R.H.D.T.E.B.D.; Gandra, É.R.D.S.; Araki, H.M.C. Nutrient digestion, microbial protein synthesis, and blood metabolites of Jersey heifers fed chitosan and whole raw soybeans. Rev. Bras. Zootec. 2016, 45, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, A.P.C.; Venturelli, B.C.; Santos, M.C.B.; Gardinal, R.; Cônsolo, N.R.B.; Calomeni, G.D.; Freitas, J.E.; Barletta, R.V.; Gandra, J.R.; Paiva, P.G.; et al. Chitosan affects total nutrient digestion and ruminal fermentation in Nellore steers. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2015, 206, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belanche, A.; Pinloche, E.; Preskett, D.; Newbold, C.J. Effects and mode of action of chitosan and ivy fruit saponins on the microbiome, fermentation and methanogenesis in the rumen simulation technique. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2016, 92, fiv160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Seghir, B.; Benhamza, M.H. Preparation, optimization and characterization of chitosan polymer from shrimp shells. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2017, 11, 1137–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, D.D.; Ruiz-Moreno, M.; Ciriaco, F.M.; Kohmann, M.; Mercadante, V.R.G.; Lamb, G.C.; DiLorenzo, N. Effects of chitosan on nutrient digestibility, methane emissions, and in vitro fermentation in beef cattle1,2. J. Anim. Sci. 2015, 93, 3539–3550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveed, M.; Phil, L.; Sohail, M.; Hasnat, M.; Baig, M.M.F.A.; Ihsan, A.U.; Shumzaid, M.; Kakar, M.U.; Mehmood Khan, T.; Akabar, M.D.; et al. Chitosan oligosaccharide (COS): An overview. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 129, 827–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philibert, T.; Lee, B.H.; Fabien, N. Current Status and New Perspectives on Chitin and Chitosan as Functional Biopolymers. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2017, 181, 1314–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puvvada, Y.S.; Vankayalapati, S.; Sukhavasi, S. Extraction of chitin from chitosan from exoskeleton of shrimp for application in the pharmaceutical industry. Int. Curr. Pharm. J. 2012, 1, 258–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cushnie, T.P.T.; Lamb, A.J. Recent advances in understanding the antibacterial properties of flavonoids. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2011, 38, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, J.; Liu, M.; Su, X.; Zhan, K.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, G. Effects of alfalfa flavonoids on the production performance, immune system, and ruminal fermentation of dairy cows. Asian Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2017, 30, 1416–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helander, I.M.; Nurmiaho-Lassila, E.-L.; Ahvenainen, R.; Rhoades, J.; Roller, S. Chitosan disrupts the barrier properties of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2001, 71, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabea, E.I.; Badawy, M.E.-T.; Stevens, C.V.; Smagghe, G.; Steurbaut, W. Chitosan as Antimicrobial Agent: Applications and Mode of Action. Biomacromolecules 2003, 4, 1457–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.-C.; Li, C.-F.; Chou, S.-S.; Chou, C.-C. Adsorption of metal cations by water-soluble N-alkylated disaccharide chitosan derivatives. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2005, 98, 564–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goy, R.C.; Britto, D.D.; Assis, O.B.G. A review of the antimicrobial activity of chitosan. Polímeros 2009, 19, 241–247. [Google Scholar]

- Raafat, D.; Sahl, H.-G. Chitosan and its antimicrobial potential—A critical literature survey. Microb. Biotechnol. 2009, 2, 186–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, M.; Chen, X.G.; Xing, K.; Park, H.J. Antimicrobial properties of chitosan and mode of action: A state of the art review. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2010, 144, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goiri, I.; Garcia-Rodriguez, A.; Oregui, L.M. Effect of chitosans on in vitro rumen digestion and fermentation of maize silage. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2009, 148, 276–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goiri, I.; Oregui, L.M.; Garcia-Rodriguez, A. Dose–response effects of chitosans on in vitro rumen digestion and fermentation of mixtures differing in forage-to-concentrate ratios. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2009, 151, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goiri, I.; Indurain, G.; Insausti, K.; Sarries, V.; Garcia-Rodriguez, A. Ruminal biohydrogenation of unsaturated fatty acids in vitro as affected by chitosan. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2010, 159, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haryati, R.P.; Jayanegara, A.; Laconi, E.B.; Ridla, M.; Suptijah, P. Evaluation of Chitin and Chitosan from Insect as Feed Additives to Mitigate Ruminal Methane Emission. In Proceedings of the AIP Conference Proceedings 2120, Malang, Indonesia, 3 July 2019; p. 040008. [Google Scholar]

- Wencelová, M.; Váradyová, Z.; Mihaliková, K.; Kišidayová, S.; Jalč, D. Evaluating the effects of chitosan, plant oils, and different diets on rumen metabolism and protozoan population in sheep. Turk. J. Vet. Anim. Sci. 2014, 38, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingoti, R.D.; Freitas, J.E.; Gandra, J.R.; Gardinal, R.; Calomeni, G.D.; Barletta, R.V.; Vendramini, T.H.A.; Paiva, P.G.; Rennó, F.P. Dose response of chitosan on nutrient digestibility, blood metabolites and lactation performance in holstein dairy cows. Livest. Sci. 2016, 187, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goiri, I.; Oregui, L.M.; Garcia-Rodriguez, A. Use of chitosans to modulate ruminal fermentation of a 50:50 forage-to-concentrate diet in sheep1. J. Anim. Sci. 2010, 88, 749–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vendramini, T.H.A.; Takiya, C.S.; Silva, T.H.; Zanferari, F.; Rentas, M.F.; Bertoni, J.C.; Consentini, C.E.C.; Gardinal, R.; Acedo, T.S.; Rennó, F.P. Effects of a blend of essential oils, chitosan or monensin on nutrient intake and digestibility of lactating dairy cows. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2016, 214, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaxter, K.L. Energy Metabolism in Animals and Man; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1989; ISBN 978-0-521-36094-4. [Google Scholar]

- Valencia Salazar, S.S.; Piñeiro Vázquez, A.T.; Molina Botero, I.C.; Lazos Balbuena, F.J.; Uuh Narváez, J.J.; Segura Campos, M.R.; Ramírez Avilés, L.; Solorio Sánchez, F.J.; Ku Vera, J.C. Potential of Samanea saman pod meal for enteric methane mitigation in crossbred heifers fed low-quality tropical grass. Agric. Meteorol. 2018, 258, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanferari, F.; Vendramini, T.H.A.; Rentas, M.F.; Gardinal, R.; Calomeni, G.D.; Mesquita, L.G.; Takiya, C.S.; Rennó, F.P. Effects of chitosan and whole raw soybeans on ruminal fermentation and bacterial populations, and milk fatty acid profile in dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 10939–10952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şenel, S.; McClure, S.J. Potential applications of chitosan in veterinary medicine. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2004, 56, 1467–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doreau, M.; van der Werf, H.M.G.; Micol, D.; Dubroeucq, H.; Agabriel, J.; Rochette, Y.; Martin, C. Enteric methane production and greenhouse gases balance of diets differing in concentrate in the fattening phase of a beef production system1. J. Anim. Sci. 2011, 89, 2518–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Chitosan | Length of Experiment | Dosage | Substrate/Feed | Methane Determination | Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| >85% deacetylated with a viscosity equal to 140 mPas in 1% acetic acid solution at 25 °C | In vitro (18 days) | 0 and 50 g/L of culture fluid | Forage-to-concentrate ratio 50:50 | Gas chromatography | 42% of reduction methane versus control, without modification of the rumen microbiota and VFA | [39] |

| Six different types | In vitro (24 and 144 h) | 750 mg/L of culture fluid | Maize silage | Stoichiometry | Modification of rumen microbial fermentation and reduced 10 to 30% of methane | [53] |

| Three different types | In vitro (24 h) | 0, 325, 750, and 1500 mg/L of culture fluid | Alfalfa hay and concentrate ratio 80:20; 50:50; 20:80 | Stoichiometry | Effects were related to the nature of the feed and the characteristics of the additive, inconsistent results in methane reduction | [54] |

| Chitin and chitosan from Black Soldier Fly | In vitro (24 h) | 10 and 20 g/L of culture fluid | Grass Setaria splendida: concentrate ratio 60:40 | Gas chromatography | Methane production was not reduced and digestibility of OM and DM were decreased | [56] |

| Deacetylated chitin, poly (D-glucosamine) Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO, USA | In vitro (24 h) | 100 mg/L of culture fluid | Meadow hay, barley grain, maize silage | Gas chromatography | Chitosan had an effect on IVDMD, total gas, slight effect on methane production, and some rumen ciliate genera | [57] |

| Deacetylation degree >95%; viscosity < 500 mPa s | In vitro (11 days) | 750 mg/d of culture fluid | Grass hay and a concentrate mixture 10:90 using sunflower or rapeseed meal | Not quantified | Chitosan inhibited biohydrogenation | [55] |

| Deacetylation degree > 95%, viscosity < 500 mPa s | In vivo, in vitro Sheep (45 days) | 0 and 136 mg/kg of BW | Alfalfa hay and concentrate at 50:50 | Stoichiometry | Chitosan reduce NDF apparent digestibility, ruminal NH3-N concentration and modulates ruminal and fecal fermentative activity | [59] |

| Degree of deacetylation > 92% apparent density 0.64 g/mL; total ash ≤ 2.0%; pH 7.0–9.0; viscosity < 200 cPs | In vivo Cattle (84 days) | 0, 50, 100 and 150 mg/kg BW | Corn Silage-concentrate 60:40 | Not quantified | Chitosan shifted rumen fermentation, improved nutrient digestibility and propionate concentrations | [38] |

| Deacetylation degree of 86.6% | In vivo Cattle (84 days) | 0 and 4 g/kg of DM | Corn silage-to- concentrate ratio 50:50 | Not quantified | Improved feed efficiency, increased milk UFA concentration | [27] |

| Deacetylation degree ≥ 85%, 0.32 g/mL density, pH 7.90, and viscosity < 200 cPs | In vivo Cattle (105 days) | 0, 400, 800, 1200 or 1600 mg/kg DM | Grazing Urochloa brizantha and concentrate at 150 g/100 kg of LW | Not quantified | Chitosan increased DMI and digestibility, propionate concentration and microbial crude protein | [28] |

| Deacetylation degree of 86.3%; 0.33 g/mL of apparent density, pH = 7.9, viscosity < 200 cPs, 1.4% ash, and 88.3% of DM | In vivo Cattle (98 days) | 0, 75, 150, 225 mg/kg BW | Corn silage to concentrate ratio 63:37 | Not quantified | In dairy cattle works like a modulator of rumen fermentation, increasing milk yield, propionate and nitrogen utilization | [29] |

| Deacetylation degree of 95%; apparent density of 0.64 g mL−1, 20 g kg−1 of ash, 7.0–9.0 of pH, viscosity < 200 cPs. | In vivo Cattle (25 days each period) | 0, 2.0 g/kg Chitosan (CH) of DM. Whole raw soybean (WRS) 163.0 g/kg DM; and CH + WRS | Corn silage to concentrate ratio 50:50 | Not quantified | Chitosan improved nutrient digestion and decrease DMI and reduce nitrogen excreted in feces | [37] |

| Deacetylation degree 90% | In vivo (21 days each period) and in vitro (24 h) | 0.0, 0.5, and 1.0% of DM | High-concentrate (85%) Low concentrate (36%) | Sulfur hexafluoride (SF6) | In vivo: No effect on enteric methane emissions. In vitro: Low concentrate substrate increased methane production | [41] |

| Deacetylation degree of 86.6%; 0.33 g/mL of apparent density, pH of 8.81 | In vivo Cattle (84 days) | 50, 100 and 150 mg/kg BW | Corn silage to concentrate ratio 50:50 | Not quantified | Improved nutrient digestibility without altering productive performance of dairy cows | [58] |

| Deacetylation degree 95%; viscosity < 200 cPs density 0.64 g/mL; pH 7.0–9.0 | In vivo Cattle (84 days) | 150 mg/kg BW | Maize silage: concentrate ratio 50:50 | Not quantified | Chitosan increase the digestibility and reduce acetate to propionate relation | [60] |

| Deacetylation degree of 86.3%; apparent density of 0.32 g/mL, pH 7.9, viscosity of 50 cP at 20 °C | In vivo Cattle (92 days) | 0 or 4 g/kg Chitosan (CH) or Whole Raw Soybean (WRS) of DM | Corn silage: concentrate ratio 50:50 | Not quantified | CH + WRS affected ruminal fermentation, increased milk content of UFA, decreases nutrient intake, digestibility, microbial protein synthesis, and milk yield. CH in diets with no lipid supplementation improves feed efficiency of lactating cows | [63] |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiménez-Ocampo, R.; Valencia-Salazar, S.; Pinzón-Díaz, C.E.; Herrera-Torres, E.; Aguilar-Pérez, C.F.; Arango, J.; Ku-Vera, J.C. The Role of Chitosan as a Possible Agent for Enteric Methane Mitigation in Ruminants. Animals 2019, 9, 942. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani9110942

Jiménez-Ocampo R, Valencia-Salazar S, Pinzón-Díaz CE, Herrera-Torres E, Aguilar-Pérez CF, Arango J, Ku-Vera JC. The Role of Chitosan as a Possible Agent for Enteric Methane Mitigation in Ruminants. Animals. 2019; 9(11):942. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani9110942

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiménez-Ocampo, Rafael, Sara Valencia-Salazar, Carmen Elisa Pinzón-Díaz, Esperanza Herrera-Torres, Carlos Fernando Aguilar-Pérez, Jacobo Arango, and Juan Carlos Ku-Vera. 2019. "The Role of Chitosan as a Possible Agent for Enteric Methane Mitigation in Ruminants" Animals 9, no. 11: 942. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani9110942

APA StyleJiménez-Ocampo, R., Valencia-Salazar, S., Pinzón-Díaz, C. E., Herrera-Torres, E., Aguilar-Pérez, C. F., Arango, J., & Ku-Vera, J. C. (2019). The Role of Chitosan as a Possible Agent for Enteric Methane Mitigation in Ruminants. Animals, 9(11), 942. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani9110942