Increasing Maximum Penalties for Animal Welfare Offences in South Australia—Has It Caused Penal Change?

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

“Extensive consultation took place with the general public and relevant organizations over the suggested amendments to this bill to ensure that appropriate measures for the welfare of animals were enforced through the proposed legislation. It was evident throughout this consultation period that the community clearly does not accept malicious behavior towards animals, with widespread support for improved measures for the welfare of animals. The irresponsible act of causing harm to an animal is deemed as a serious offence by this community and this government. The proposed changes to this bill reflect the public’s concerns”.

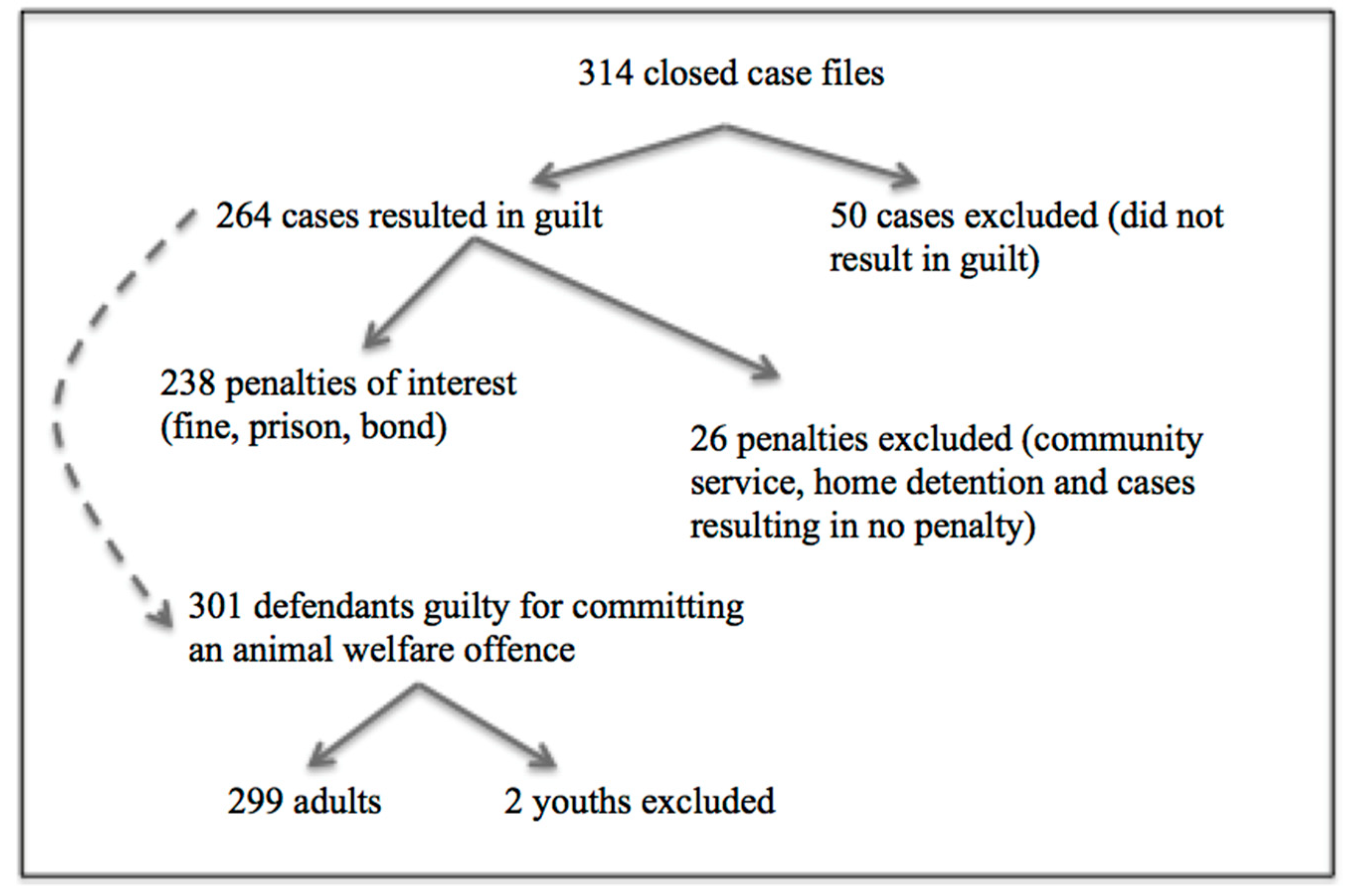

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Statement

2.2. Terminology

- (1)

- If—

- (a)

- a person ill-treats an animal; and

- (b)

- the ill treatment causes the death of, or serious harm to, the animal; and

- (c)

- the person intends to cause, or is reckless about causing, the death of, or serious harm to, the animal, the person is guilty of an offence.Maximum penalty: $50,000 or imprisonment for 4 years.

- (2)

- A person who ill-treats an animal is guilty of an offence. Maximum penalty: $20,000 or imprisonment for 2 years.

2.3. Amended Changes

2.4. Data Collection

- (3) Without limiting the generality of subsection (1) or (2), a person ill-treats an animal if the person—

- (a)

- intentionally, unreasonably or recklessly causes the animal unnecessary harm; or

- (b)

- being the owner of the animal—

- (i)

- fails to provide it with appropriate, and adequate, food, water, living conditions (whether temporary or permanent) or exercise; or

- (ii)

- fails to take reasonable steps to mitigate harm suffered by the animal; or

- (iii)

- abandons the animal; or

- (iv)

- neglects the animal so as to cause it harm; or

- (c)

- having caused the animal harm (not being an animal of which that person is the owner), fails to take reasonable steps to mitigate the harm; or

- (f)

- causes the animal to be killed or injured by another animal; or

- (g)

- kills the animal in a manner that causes the animal unnecessary pain; or

- (h)

- unless the animal is unconscious, kills the animal by a method that does not cause death to occur as rapidly as possible; or

- (i)

- carries out a medical or surgical procedure on the animal in contravention of the regulations; or

- (j)

- ill-treats the animal in any other manner prescribed by the regulations for the purposes of this section.

2.5. Data Processing

2.6. Data Analysis

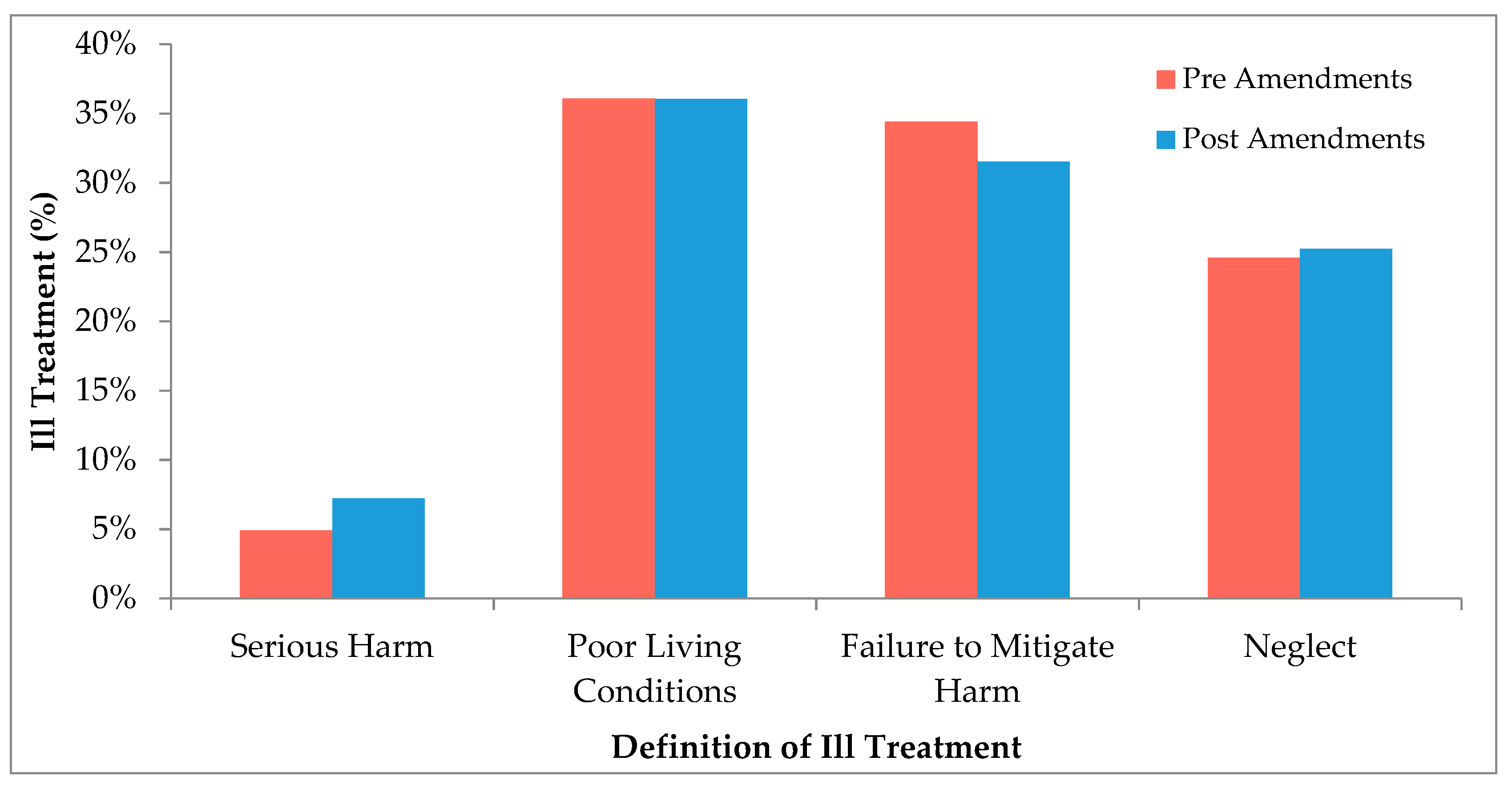

3. Results

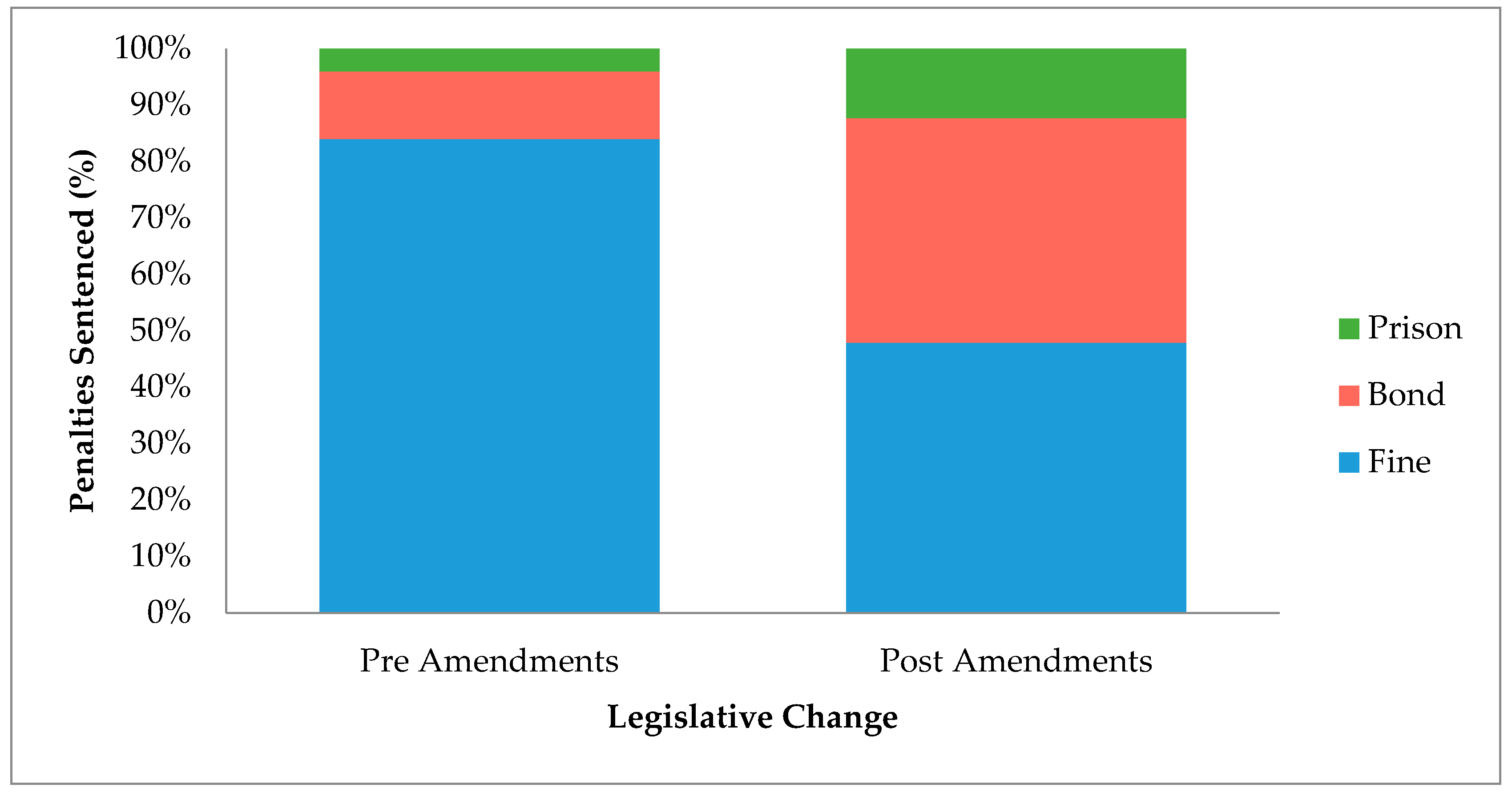

3.1. Changes to the Type of Penalty Imposed

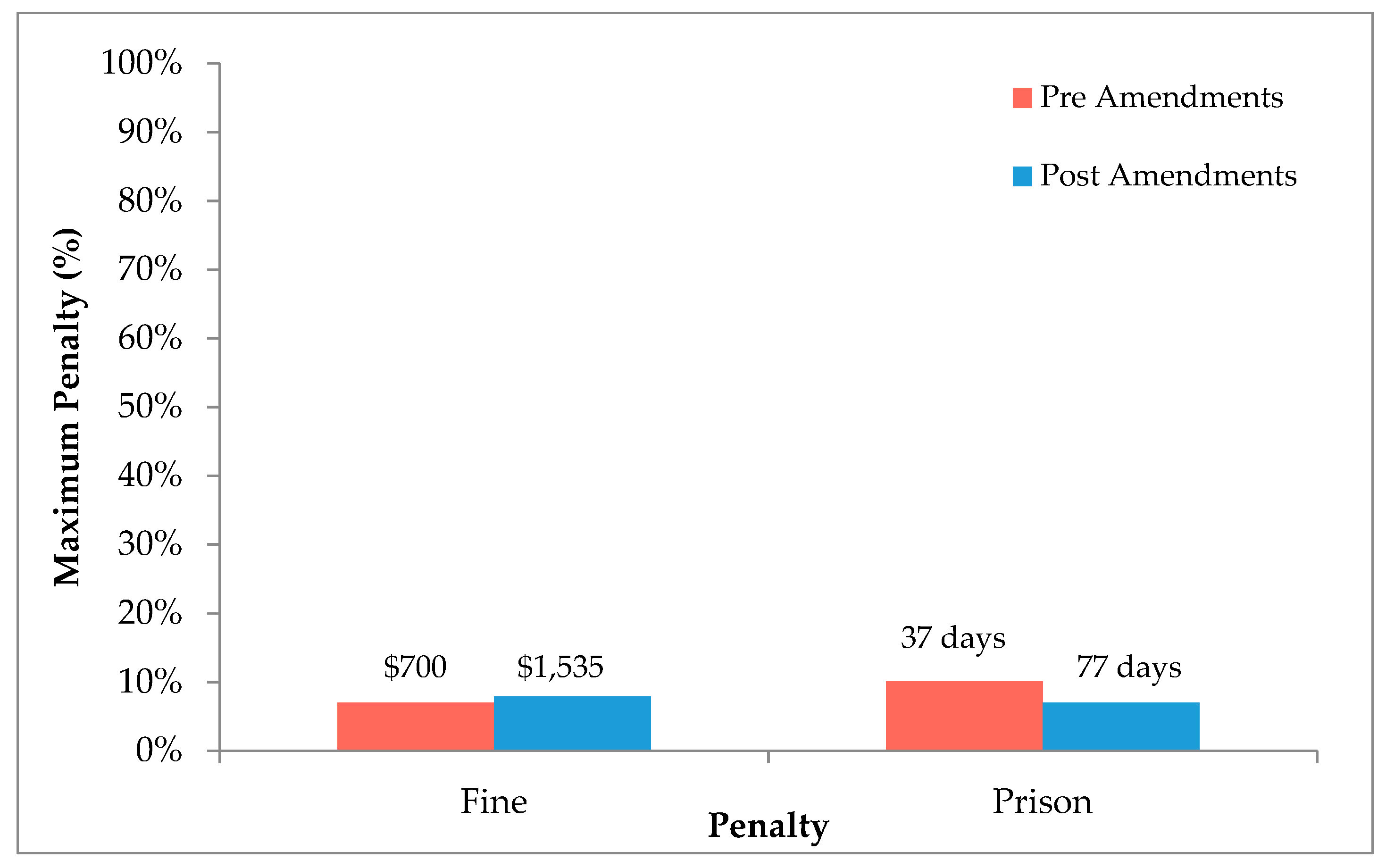

3.2. Penalties Relative to the Maximum Penalty

3.3. Animal Species and Penalties

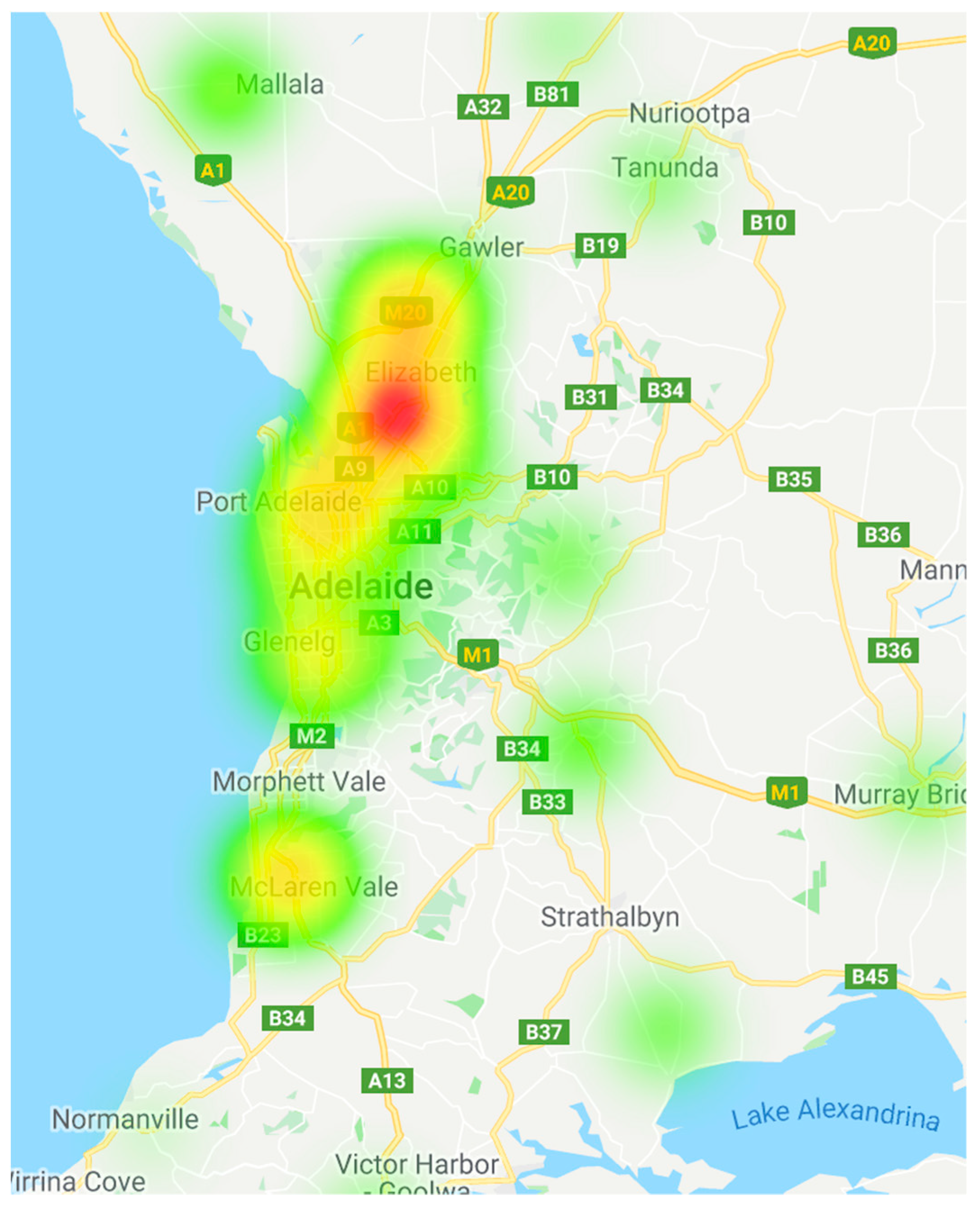

3.4. Demographic Trends

4. Discussion

4.1. Shifts in Penalties Imposed

“The usual outcome on a plea of guilty to this offence is the imposition of a fine. The fact that Parliament has set $20,000 as the maximum fine and that was the subject of an amendment within the last few years, I think, where the maximum financial penalty was raised from $10,000 to $20,000, the fact that Parliament did that reflects the concern of the community as to the ill treatment of animals. It is a matter which the community—and in this I include yourself—regard as being something that should be severely punished”.

- Subject to this Act or any other Act, a court must not impose a sentence of imprisonment on a defendant unless the court decides that:

- (a)

- the seriousness of the offence is such that the only penalty that can be justified is imprisonment; or

- (b)

- it is required for the purpose of protecting the safety of the community (whether as individuals or in general).

4.2. Penalties Relative to the Maximum Penalty

4.3. Is Animal Law Speciesist?

4.4. Demographic Trends

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References and Notes

- Taylor, N.; Signal, T.D. Lock ‘em up and throw away the key? Community opinions regarding current animal abuse penalties. Aust. Anim. Prot. Law J. 2009, 3, 33–52. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, S.K.T.; Sims, V.K.; Chin, M.G. Predictors of views about punishing animal abuse. Anthrozoös 2016, 29, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, V.K.; Chin, M.G.; Yordon, R.E. Don’t be cruel: Assessing beliefs about punishments for crimes against animals. Anthrozoös 2007, 20, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, M.; Hunstone, M.; Waerstad, J.; Foy, E.; Hobbins, T.; Wikner, B.; Wirrel, J. Human-to-animal similarity and participant mood influence punishment recommendations for animal abusers. Soc. Anim. 2002, 10, 267–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, E. Making sausages & law: The failure of animal welfare laws to protect both animals and fundamental tenets of Australia’s legal system. Aust. Anim. Prot. Law J. 2010, 4, 6–26. [Google Scholar]

- Sharman, K. Sentencing under our anti-cruelty statutes: Why our leniency will come back to bite us. Curr. Issues Crim. Justice 2002, 13, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, D. Animal Law in Australia, 2nd ed.; Sharman, K., White, S.W., Eds.; Thomson Reuters: Sydney, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Vollum, S.; Buffington-Vollum, J.; Longmire, D. Moral disengagement and attitudes about violence toward animals. Soc. Anim. 2004, 12, 209–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- South Australia Legislative Council. Bills: Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (Animal Welfare) Amendment Bill—13/11/2007. Available online: https://hansardpublic.parliament.sa.gov.au/Pages/HansardResult.aspx-/docid/HANSARD-10-282 (accessed on 9 April 2018).

- South Australia House of Assembly. Bills: Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (Animal Welfare) Amendment Bill—3/6/2008. Available online: https://hansardpublic.parliament.sa.gov.au/Pages/HansardResult.aspx-/docid/HANSARD-11-1743 (accessed on 9 April 2018).

- Morgan, N. Sentencing Trends for Violent Offenders in Australia. 2002. Available online: http://crg.aic.gov.au/reports/2002-Morgan.pdf (accessed on 13 October 2018).

- Sankoff, P. Five years of the new animal welfare regime: Lessons learned from New Zealand’s decision to modernize its animal welfare legislation. Anim. Law 2005, 11, 7–38. [Google Scholar]

- Boom, K.; Ellis, E. Enforcing animal welfare law: The NSW experience. Aust. Anim. Prot. Law J. 2009, 3, 6–32. [Google Scholar]

- Geysen, T.-L.; Weick, J.; White, S. Companion animal cruelty and neglect in Queensland: Penalties, sentencing and “community expectations”. Aust. Anim. Prot. Law J. 2010, 4, 46–63. [Google Scholar]

- Markham, A. Animal Cruelty Sentencing in Australia and New Zealand. In Animal Law in Australasia: A New Dialogue; Sankoff, P.J., White, S.W., Eds.; Federation Press: Sydney, Australia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Arluke, A.; Luke, C. Physical cruelty toward animals in Massachusetts, 1975–1996. Soc. Anim. 1997, 5, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Health and Medical Research Council. National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research. Updated July 2018. Available online: https://nhmrc.gov.au/about-us/publications/national-statement-ethical-conduct-human-research-2007-updated-2018 (accessed on 9 October 2018).

- Ind, D.; RSPCA (SA) Legal Counsel, Adelaide, South Australia, Australia. Personal communication, 2018.

- Freiberg, A.; Ross, S. Sentencing Reform and Penal Change: The Victorian Experience; Federation Press: Leichhardt, Australia, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- RSPCA v Crisp (2010) SAMC (unreported, Forrest J, 4 November 2010).

- Triggs, S. Sentencing in New Zealand: A Statistic Analysis; Ministry of Justice: Wellington, New Zealand, 1999.

- Halliday, J. Making Punishments Work: Report of a Review of the Sentencing Framework for England and Wales; Home Office: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Livingston, M. Desecrating the ark: Animal abuse and the law’s role in prevention. IOWA Law Rev. 2001, 87, 1649. [Google Scholar]

- DeGue, S.; DiLillo, D. Is animal cruelty a “red flag” for family violence? J. Interpers. Violence 2009, 24, 1036–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Febres, J.; Brasfield, H.; Shorey, R.C.; Elmquist, J.; Ninnemann, A.; Schonbrun, Y.C.; Temple, J.R.; Recupero, P.R.; Stuart, G.L. Adulthood animal abuse among men arrested for domestic violence. Violence Against Women 2014, 20, 1059–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flynn, C. Examining the links between animal abuse and human violence. Crime Law Soc. Chang. 2011, 55, 453–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newberry, M. Pets in danger: Exploring the link between domestic violence and animal abuse. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2017, 34, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volant, A.M.; Johnson, J.A.; Gullone, E.; Coleman, G.J. The relationship between domestic violence and animal abuse: An Australian study. J. Interpers. Violence 2008, 23, 1277–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton-Moss, B.; Manganello, J.; Frye, V.; Campbell, J. Risk factors for intimate partner violence and associated injury among urban women. Publ. Health Promot. Dis. Prev. 2005, 30, 377–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, J.; Hensley, C. From animal cruelty to serial murder: Applying the graduation hypothesis. Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. Criminol. 2003, 47, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macias-Mayo, A.R. The link between animal abuse and child abuse. Am. J. Fam. Law 2018, 32, 130. [Google Scholar]

- Levitt, L.; Hoffer, T.A.; Loper, A.B. Criminal histories of a subsample of animal cruelty offenders. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2016, 30, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bregant, J.; Shaw, A.; Kinzler, K.D. Intuitive jurisprudence: Early reasoning about the functions of punishment. J. Empir. Leg. Stud. 2016, 13, 693–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escamilla-Castillo, M. The purposes of legal punishment. Ratio Juris 2010, 23, 460–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylvia, R. Corporate criminals and punishment theory. Can. J. Law Jurisprud. 2016, 29, 97–245. [Google Scholar]

- Zaibert, L. Beyond bad: Punishment theory meets the problem of evil. Midwest Stud. Philos. 2012, 36, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paternoster, R. How much do we really know about criminal deterrence? J. Crim. Law Criminol. 2010, 100, 765. [Google Scholar]

- Horta, O. What is speciesism? J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2010, 23, 243–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, N.; Signal, T.D. Pet, pest, profit: Isolating differences in attitudes towards the treatment of animals. Anthrozoös 2009, 22, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellert, S. American attitudes and knowledge of animals: An update. Int. J. Stud. Anim. Probl. 1980, 1, 87–119. [Google Scholar]

- RSPCA v Harrison (1999) 204 LSJS 345.

- Jones v Manchester Corp (1952) 2 QB 852.

- Henry, B.; Sanders, C. Bullying and animal abuse: Is there a connection? Soc. Anim. 2007, 15, 107–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, R.L.; Fremouw, W.; Schenk, A.; Ragatz, L.L. Psychological profile of male and female animal abusers. J. Interpers. Violence 2012, 27, 846–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tallichet, S.E.; Hensley, C. Rural and urban differences in the commission of animal cruelty. Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. Criminol. 2005, 49, 711–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tallichet, S.E.; Hensley, C.; Evans, R.A. Place-based differences in the commission of recurrent animal cruelty. Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. Criminol. 2012, 56, 1283–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tallichet, S.E.; Hensley, C.; O’Bryan, A.; Hassel, H. Targets for cruelty: Demographic and situational factors affecting the type of animal abused. Crim. Justice Stud. 2005, 18, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grugan, S.T. The companions we keep: A situational analysis and proposed typology of companion animal cruelty offences. Deviant Behav. 2017, 39, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Hills, A.M.; Lalich, N.M. Judgments of cruelty toward animals: Sex differences and effect of awareness of suffering. Anthrozoös 1998, 11, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, E.S. Empathy with animals and with humans: Are they linked? Anthrozoös 2000, 13, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, N.; Signal, T.D. Empathy and attitudes to animals. Anthrozoös 2005, 18, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, N.; Signal, T.D. Attitudes to animals: Demographics within a community sample. Soc. Anim. 2006, 14, 147–157. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, N.; Signal, T.D. Community demographics and the propensity to report animal cruelty. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2006, 9, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, H.A. Gender differences in human—Animal interactions: A review. Anthrozoös 2007, 20, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijk, A.; Hardeman, M.; Endenburg, N. Animal abuse: Offender and offence characteristics. A descriptive study. J. Investig. Psychol. Offender Profil. 2018, 15, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Census of Population and Housing: Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA), Australia. 2016. Available online: http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/by Subject/2033.0.55.001~2016~Main Features~IRSAD Interactive Map~16 (accessed on 15 October 2018).

- Bradley, H.; RSPCA (SA) Education Officer, Adelaide, South Australia, Australia. Personal communication, 2017.

| Offence Characteristics | Section 13(1) | Section 13(2) |

|---|---|---|

| Severity | Higher | Lower |

| Offence Type * | Aggravated | Basic |

| Max. Monetary Fine | $50,000.00 | $20,000.00 |

| Max. Custodial Sentence | 4 years | 2 years |

| Offence Type | Pre Amendments | Post Amendments |

|---|---|---|

| Aggravated | - | 4 years imprisonment $50,000 fine |

| Basic | 1 year imprisonment $10,000 fine | 2 years imprisonment $20,000 fine |

| Category | Definition | Example Species |

|---|---|---|

| Companion | Animals that are under human control, providing companionship to human-owners | Dog, Rabbit, Horse |

| Farm | Animals commonly used for meat, eggs, milk, fur, or fibre production, providing either companionship or profit to human-owners | Sheep, Cattle |

| Wild | Animals that reside in the wild and are not under the control of a human-owner | Possum, Kangaroo |

| Exotic | Animals that are under human control, but do not fit the usual description of a ‘companion animal’ | Snake, Bird |

| Species Category | Fine | Prison |

|---|---|---|

| Companion | $703.71 (132) | 40 days (35) |

| Farm | $1321.13 (53) | 105 days (2) |

| Gender | Aggravated | Basic |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 13 (76%) | 159 (56%) |

| Female | 4 (24%) | 123 (44%) |

| Overall | 17 | 282 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Morton, R.; Hebart, M.L.; Whittaker, A.L. Increasing Maximum Penalties for Animal Welfare Offences in South Australia—Has It Caused Penal Change? Animals 2018, 8, 236. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani8120236

Morton R, Hebart ML, Whittaker AL. Increasing Maximum Penalties for Animal Welfare Offences in South Australia—Has It Caused Penal Change? Animals. 2018; 8(12):236. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani8120236

Chicago/Turabian StyleMorton, Rochelle, Michelle L. Hebart, and Alexandra L. Whittaker. 2018. "Increasing Maximum Penalties for Animal Welfare Offences in South Australia—Has It Caused Penal Change?" Animals 8, no. 12: 236. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani8120236

APA StyleMorton, R., Hebart, M. L., & Whittaker, A. L. (2018). Increasing Maximum Penalties for Animal Welfare Offences in South Australia—Has It Caused Penal Change? Animals, 8(12), 236. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani8120236