Does Nose Work Training Affect Dog Executive Function and Physical Fitness in Humans and Dogs?

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

- Are self-taught in nose work;

- Are or have been enrolled in an instructor-led nose work class;

- Have completed any title in a nose work-type sport, including but not limited to those granted by the National Association of Canine Scent Work (NACSW), Barn Hunt Association, and American Kennel Club.

2.2. Human Testing

2.2.1. 6 Min Walk Test

2.2.2. 30 s Chair Stand Test

2.2.3. Hand Strength

2.3. Questionnaire

2.4. Dog Testing

2.4.1. Cognitive Tests

2.4.2. Unsolvable Task

2.4.3. Object Choice Task

2.4.4. Fitness Tests

2.4.5. Back-Up Test

2.4.6. Progressive Squat Test

2.5. Body Condition Assessment

2.6. Post Testing

2.7. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographics of the Dogs and Humans

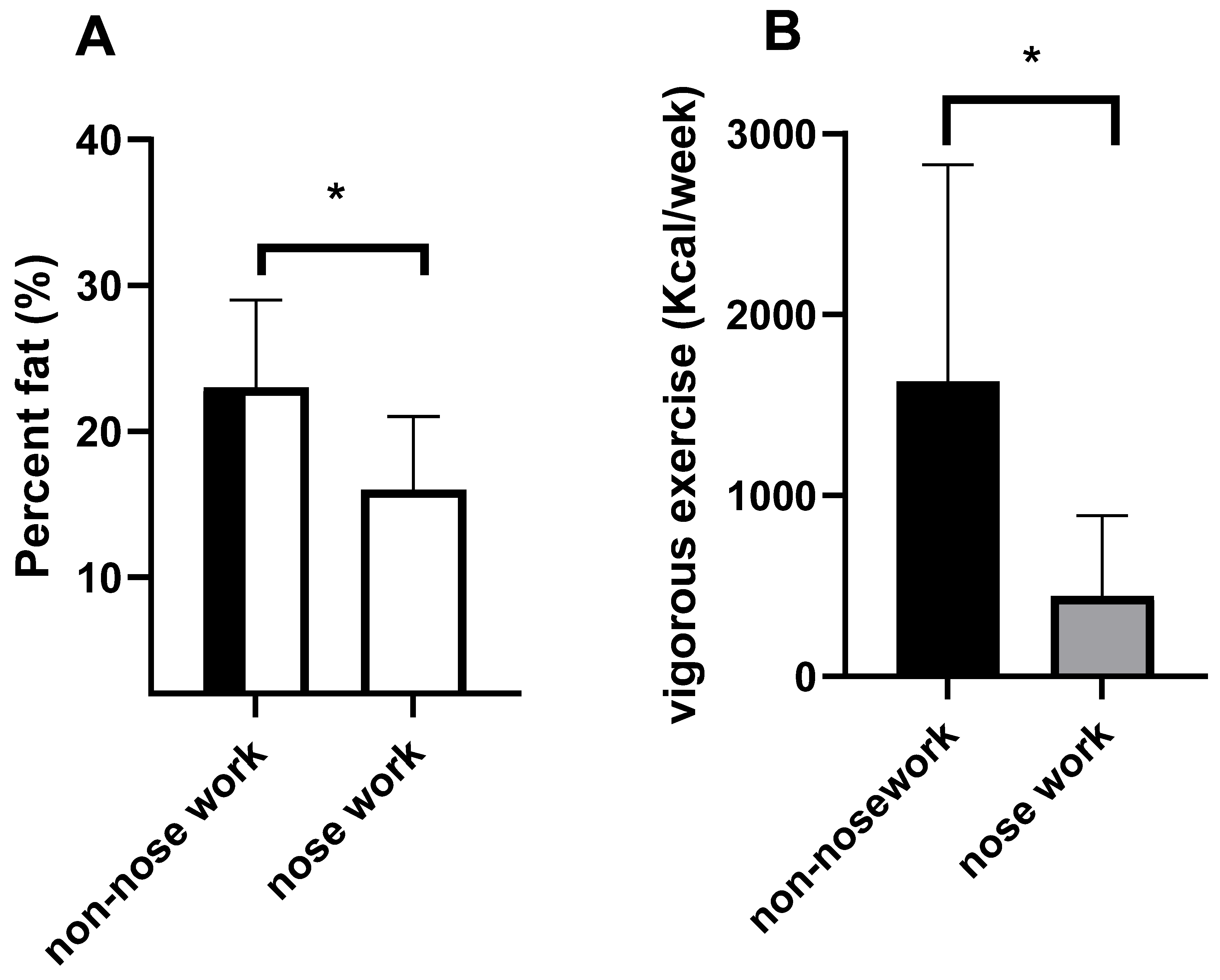

3.2. Human Fitness

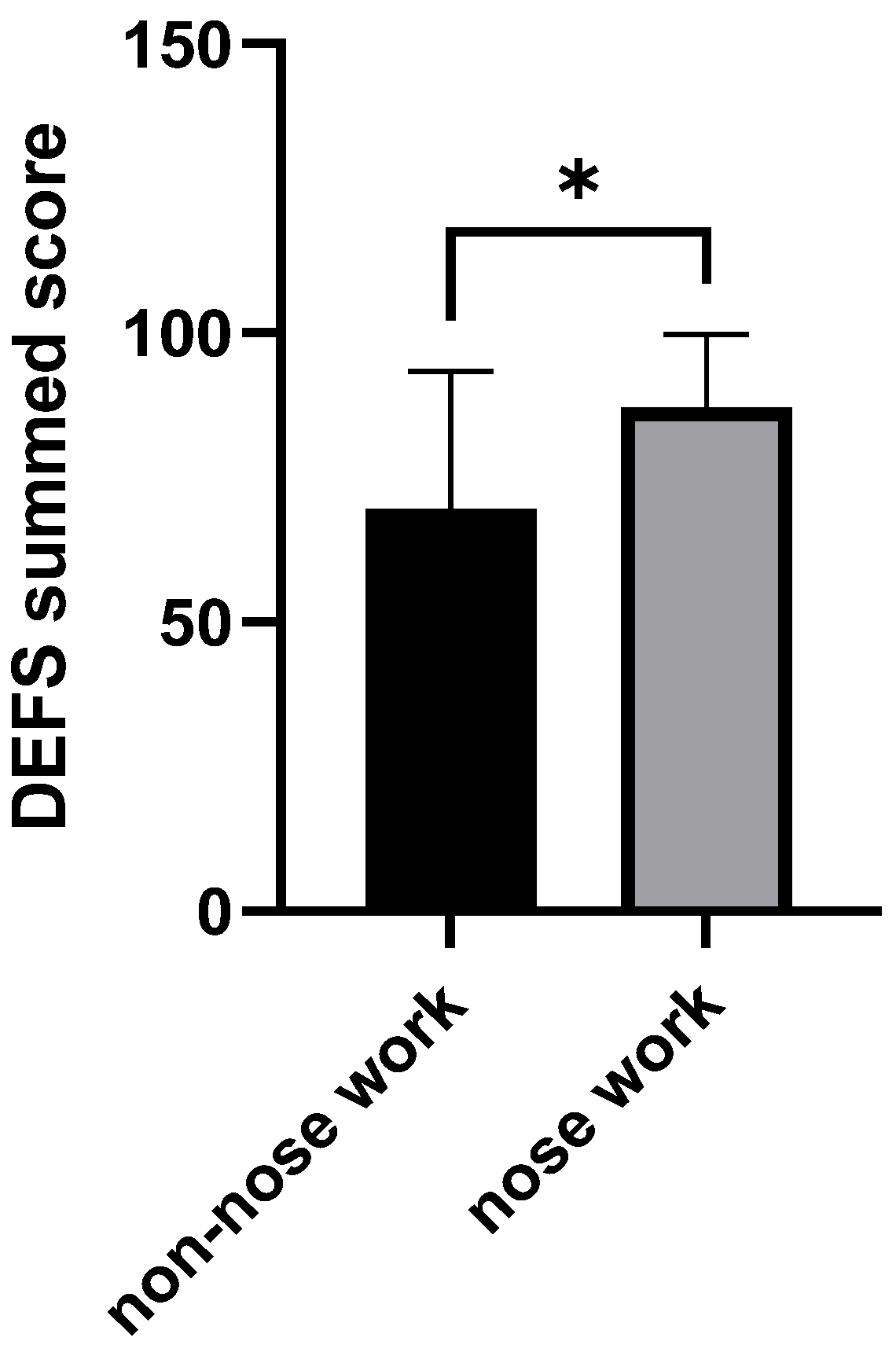

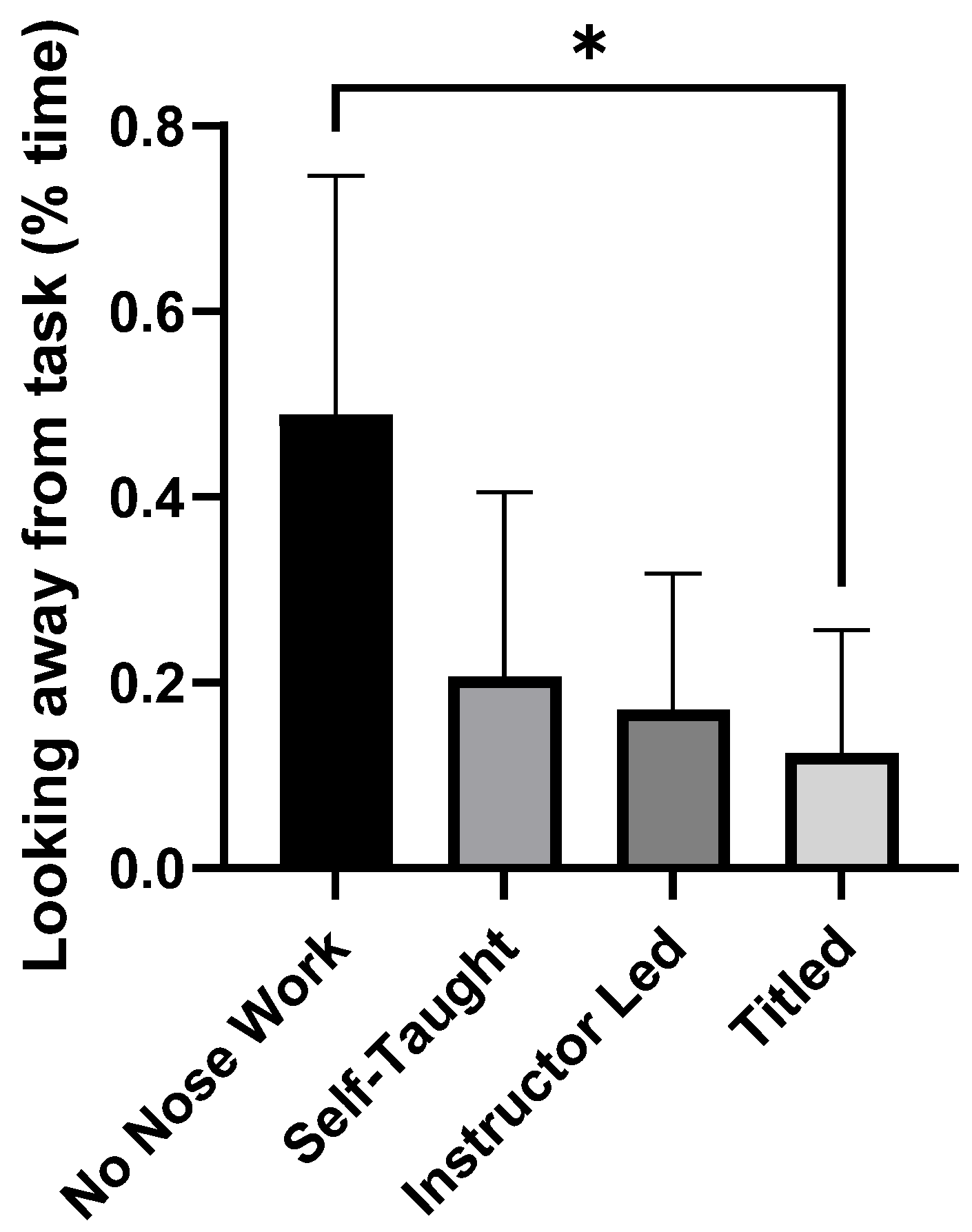

3.3. Dog Cognition

3.4. Dog Fitness Tests

3.5. Correlations

3.6. Reliability of Tests over Time

4. Discussion

4.1. Fitness Tests

4.2. Cognitive Tests

4.3. Reliability of Measures over Time

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fountain, J.; Fernandez, E.J.; McWhorter, T.J.; Hazel, S.J. The value of sniffing: A scoping review of scent activities for canines. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2025, 282, 106485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, E.K.; DeChant, M.T.; Perry, E.B. When the Nose Doesn’t Know: Canine Olfactory Function Associated with Health, Management, and Potential Links to Microbiota. Front. Vet. Sci. 2018, 5, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcellin-Little, D.J.; Levine, D.; Taylor, R. Rehabilitation and conditioning of sporting dogs. Vet. Clin. Small Anim. Pract. 2005, 35, 1427–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.S.; Kim, J.H. The dog as an exercise science animal model: A review of physiological and hematological effects of exercise conditions. Phys. Act. Nutr. 2020, 24, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baltzer, W. Preventing injury in sporting dogs. Vet. Med. 2012, 107, 178–183. [Google Scholar]

- Kluess, H.A.; Jones, R.L. Health and Benefits of Dog Companionship in Women over 50 Years Old. J. Ageing Longev. 2024, 4, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enright, P.L.; Sherrill, D.L. Reference equations for the six-minute walk in healthy adults. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1998, 158, 1384–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohannon, R.W. Six-minute walk test—A meta-analysis of data from apparently healthy elders. Top. Geriatr. Rehabil. 2007, 23, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manens, J.; Ricci, R.; Damoiseaux, C.; Gault, S.; Contiero, B.; Diez, M.; Clercx, C. Effect of Body Weight Loss on Cardiopulmonary Function Assessed by 6-Minute Walk Test and Arterial Blood Gas Analysis in Obese Dogs. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2014, 28, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swimmer, R.A.; Rozanski, E.A. Evaluation of the 6-Minute Walk Test in Pet Dogs. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2011, 25, 405–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lein, D.H., Jr.; Alotaibi, M.; Almutairi, M.; Singh, H. Normative Reference Values and Validity for the 30-Second Chair-Stand Test in Healthy Young Adults. Int. J. Sports Phys. Ther. 2022, 17, 907–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.J.; Rikli, R.E.; Beam, W.C. A 30-s chair-stand test as a measure of lower body strength in community-residing older adults. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 1999, 70, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanagawa, N.; Shimomitsu, T.; Kawanishi, M.; Fukunaga, T.; Kanehisa, H. Relationship between performances of 10-time-repeated sit-to-stand and maximal walking tests in non-disabled older women. J. Physiol. Anthr. 2016, 36, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohannon, R.W.; Wang, Y.C.; Yen, S.C.; Grogan, K.A. Handgrip Strength: A Comparison of Values Obtained From the NHANES and NIH Toolbox Studies. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2019, 73, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, B.M.; Stalling, I.; Bammann, K. Sex- and age-specific normative values for handgrip strength and components of the Senior Fitness Test in community-dwelling older adults aged 65–75 years in Germany: Results from the OUTDOOR ACTIVE study. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, K.M.; Rishniw, M.; McMullin, K.M.; Venator, K.R.; Juran, I.G.; Dudek, M.; Miller, A.V.; Lenfest, M.I.; Frye, C.W. Timed Up and Go demonstrates strong repeatability and correlates with vigorous activity as measured by accelerometry in geriatric dogs. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2025, 86, ajvr.25.02.0041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMullin, K.M.; Carney, P.C.; Juran, I.G.; Venator, K.R.; Miller, A.V.; Lenfest, M.I.; Carr, B.J.; Frye, C.W. Timed up and go demonstrates strong interrater agreement and criterion validity as a functional test in geriatric dogs. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2024, 85, ajvr.24.03.0062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poole, D.C.; Copp, S.W.; Colburn, T.D.; Craig, J.C.; Allen, D.L.; Sturek, M.; O’Leary, D.S.; Zucker, I.H.; Musch, T.I. Guidelines for animal exercise and training protocols for cardiovascular studies. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2020, 318, H1100–H1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radin, L.; Belic, M.; Brkljaca Bottegaro, N.; Hrastic, H.; Torti, M.; Vucetic, V.; Stanin, D.; Vrbanac, Z. Heart rate deflection point during incremental test in competitive agility border collies. Vet. Res. Commun. 2015, 39, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farr, B.D.; Ramos, M.T.; Otto, C.M. The Penn Vet Working Dog Center Fit to Work Program: A Formalized Method for Assessing and Developing Foundational Canine Physical Fitness. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foraita, M.; Howell, T.; Bennett, P. Environmental influences on development of executive functions in dogs. Anim. Cogn. 2021, 24, 655–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szabó, D.; Miklósi, A.; Kubinyi, E. Owner reported sensory impairments affect behavioural signs associated with cognitive decline in dogs. Behav. Process 2018, 157, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapagain, D.; Wallis, L.J.; Range, F.; Affenzeller, N.; Serra, J.; Viranyi, Z. Behavioural and cognitive changes in aged pet dogs: No effects of an enriched diet and lifelong training. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0238517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duranton, C.; Horowitz, A. Let me sniff! Nosework induces positive judgment bias in pet dogs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2019, 211, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarowski, L.; Strassberg, L.R.; Waggoner, L.P.; Katz, J.S. Persistence and human-directed behavior in detection dogs: Ontogenetic development and relationships to working dog success. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2019, 220, 104860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiira, K.; Tikkanen, A.; Vainio, O. Inhibitory control—Important trait for explosive detection performance in police dogs? Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2020, 224, 104942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carballo, F.; Cavalli, C.M.; Gácsi, M.; Miklósi, A.; Kubinyi, E. Assistance and Therapy Dogs Are Better Problem Solvers Than Both Trained and Untrained Family Dogs. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalli, C.; Carballo, F.; Dzik, M.V.; Bentosela, M. Gazing as a help requesting behavior: A comparison of dogs participating in animal-assisted interventions and pet dogs. Anim. Cogn. 2020, 23, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarowski, L.; Dorman, D.C. A comparison of pet and purpose-bred research dog performance on human-guided object-choice tasks. Behav. Process 2015, 110, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedel, J.; Schumann, K.; Kaminski, J.; Call, J.; Tomasello, M. The early ontogeny of human-dog communication. Anim. Behav. 2008, 75, 1003–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passalacqua, C.; Marshall-Pescini, S.; Barnard, S.; Lakatos, G.; Valsecchi, P.; Previde, E.P. Human-directed gazing behaviour in puppies and adult dogs. Anim. Behav. 2011, 82, 1043–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junttila, S.; Valros, A.; Maki, K.; Vaataja, H.; Reunanen, E.; Tiira, K. Breed differences in social cognition, inhibitory control, and spatial problem-solving ability in the domestic dog (Canis familiaris). Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 22529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, L.; MacLean, E.L.; Ivy, D.; Woods, V.; Cohen, E.; Rodriguez, K.; McIntyre, M.; Mukherjee, S.; Call, J.; Kaminski, J.; et al. Citizen Science as a New Tool in Dog Cognition Research. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0135176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foraita, M.; Howell, T.; Bennett, P. Development of the dog executive function scale (DEFS) for adult dogs. Anim. Cogn. 2022, 25, 1479–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foraita, M.; Howell, T.; Bennett, P. Executive Functions as Measured by the Dog Executive Function Scale (DEFS) over the Lifespan of Dogs. Animals 2023, 13, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/physical-activity-basics/measuring/ (accessed on 29 December 2023).

- Marshall-Pescini, S.; Valsecchi, P.; Petak, I.; Accorsi, P.A.; Previde, E.P. Does Training Make You Smarter? The Effects of Training on Dogs’ Performance (Canis familiaris) in a Problem Solving Task. Behav. Process. 2008, 78, 449–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall-Pescini, S.; Frazzi, C.; Valsecchi, P. The effect of training and breed group on problem-solving behaviours in dogs. Anim. Cogn. 2016, 19, 571–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Range, F.; Heucke, S.L.; Gruber, C.; Konz, A.; Huber, L.; Virányi, Z. The effect of ostensive cues on dogs’ performance in a manipulative social learning task. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2009, 120, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapagain, D.; Virányi, Z.; Wallis, L.J.; Huber, L.; Serra, J.; Range, F. Aging of Attentiveness in Border Collies and Other Pet Dog Breeds: The Protective Benefits of Lifelong Training. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2017, 9, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarowski, L.; Thompkins, A.; Krichbaum, S.; Waggoner, L.P.; Deshpande, G.; Katz, J.S. Comparing pet and detection dogs (Canis familiaris) on two aspects of social cognition. Learn. Behav. 2020, 48, 432–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kluess, H.A.; Jones, R.L. A comparison of owner perceived and measured body condition, feeding and exercise in sport and pet dogs. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1211996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluess, H.A.; Jones, R.L.; Lee-Fowler, T. Perceptions of Body Condition, Diet and Exercise by Sports Dog Owners and Pet Dog Owners. Animals 2021, 11, 1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mawby, D.I.; Bartges, J.W.; d’Avignon, A.; Laflamme, D.P.; Moyers, T.D.; Cottrell, T. Comparison of various methods for estimating body fat in dogs. J. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc. 2004, 40, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blain, H.; Jaussent, A.; Picot, M.C.; Maimoun, L.; Coste, O.; Masud, T.; Bousquet, J.; Bernard, P.L. Effect of a 6-month brisk walking program on walking endurance in sedentary and physically deconditioned women aged 60 or older: A randomized trial. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2017, 21, 1183–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Association of Canine Scent Work Education Division. Available online: https://k9nosework.com/ (accessed on 9 October 2025).

| Training Experience | Point Value |

|---|---|

| Human companion’s estimated training level | Multiply by 2 for point value |

| Each sport dog participates in with at least one title earned | 1 point for each |

| Each sport dog participates in with no titles earned | 0.5 point for each |

| Each listed title earned | 0.5 point for each |

| Any CH (champion)-level title (MACH, RACH, ADCH, OTCH, etc.) | 2 points each |

| Dog knows the behaviors: sit, down, shake, walk on leash | 0.25 point each |

| Dog knows any other behaviors listed | 0.5 point each |

| Experience with puzzle/mental stimulation type toys | 0.25 point for “barely experienced: 0.5 point for “somewhat experienced” 1 point for “experienced” or “very experienced” |

| Each life stage indicated where dog attended any formal professional training | 0.5 point |

| Clicker training | 1 point |

| Sum = training level score | |

| Non-Nose Work Group (n = 7) | Nose Work Group (n = 19) | |

|---|---|---|

| Dog age | 4 ± 2 years | 4 ± 3 years |

| Dog sex Male (M)/Female (F) | M = 4/F = 3 | M = 10/F = 9 |

| Intact (I)/desexed (D) | I = 1/D = 6 | I = 5/D = 14 |

| Purebred (P)/mixed breed (mix) | P = 5/Mix = 2 | P = 15/Mix = 4 |

| Moderate exercise | 480 ± 358 kcal/week | 541 ± 676 kcal/week |

| Non-Nose Work Group (n = 7) | Nose Work Group (n = 19) | |

|---|---|---|

| Training rubric | 12 ± 7 | 27 ± 9 |

| Years in dog sports (Human) | Never competed n = 2 Less than year n = 3 1–3 years n = 2 | Never competed n = 0 |

| Less than year n = 2 | ||

| 1–3 years n = 7 | ||

| 3–5 years n = 2 | ||

| 5–7 years n = 3 | ||

| 10+ years n = 5 | ||

| Sports competed | Never competed n = 3 | Never competed n = 0 |

| Obedience n = 1 | Obedience n = 4 | |

| Rally obedience n = 2 | Rally obedience n = 5 | |

| Herding n = 0 | Herding n = 1 | |

| Dock diving n = 3 | Dock diving n = 9 | |

| Agility n = 0 | Agility n = 4 | |

| Barn Hunt n = 0 | Barn Hunt n = 7 | |

| Scent Work n = 0 | Scent Work n = 10 | |

| IPO n = 0 | IPO n = 1 | |

| FastCat n = 1 | FastCat n = 11 | |

| Lure Coursing n = 1 | Lure Coursing n = 1 | |

| Conformation n = 1 | Conformation n = 2 | |

| Trick Dog n = 0 | Trick Dog n = 11 | |

| Disc sports n = 1 | Disc sports n = 4 | |

| Other n = 2 | Other n = 2 | |

| Titles | n = 5 sports with titles | n = 40 sports with titles |

| Nose/scent work currently enrolled in classes | none | Yes n = 10/No n = 9 |

| Years training in nose/scent work with an instructor | none | 5 years n = 2 |

| 3 years n = 2 | ||

| 1–2 year n = 3 | ||

| less than 1 year n = 4 | ||

| none n = 8 | ||

| Hours per week with an instructor | none | 1.25 ± 0.50 h per week, n = 12 None = 7 |

| Did they do informal practice | none | Yes n = 18, No n = 1 |

| Total years of nose work practice (Human; can be multiple dogs) | none | 5+ years n = 3 |

| 3–4 years n = 3 | ||

| 1–2 years n = 3 | ||

| less than 1 year n = 9 | ||

| no answer n = 1 | ||

| Years the current dog trained in nose/scent work | none | 4–5 years n = 2 |

| 1–3 years n = 6 | ||

| Less than 1 year n = 11 | ||

| Current nose/scent work titles | none | AKC excellent n = 5 |

| NACSW NW3 n = 1 | ||

| AKC advanced n = 5 | ||

| NACSW NW2 n = 1 | ||

| NACSW NW1 n = 3 | ||

| AKC novice n = 5 | ||

| NACSW ORT n = 3 | ||

| Other related titles n = 6 | ||

| No titles n = 13 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kluess, H.A.; Neff, A.H. Does Nose Work Training Affect Dog Executive Function and Physical Fitness in Humans and Dogs? Animals 2026, 16, 453. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16030453

Kluess HA, Neff AH. Does Nose Work Training Affect Dog Executive Function and Physical Fitness in Humans and Dogs? Animals. 2026; 16(3):453. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16030453

Chicago/Turabian StyleKluess, Heidi A., and Alexandra Hackett Neff. 2026. "Does Nose Work Training Affect Dog Executive Function and Physical Fitness in Humans and Dogs?" Animals 16, no. 3: 453. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16030453

APA StyleKluess, H. A., & Neff, A. H. (2026). Does Nose Work Training Affect Dog Executive Function and Physical Fitness in Humans and Dogs? Animals, 16(3), 453. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16030453