Response of an Apex Mammalian Predator to an Emergence of 13-Year Periodical Cicadas

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

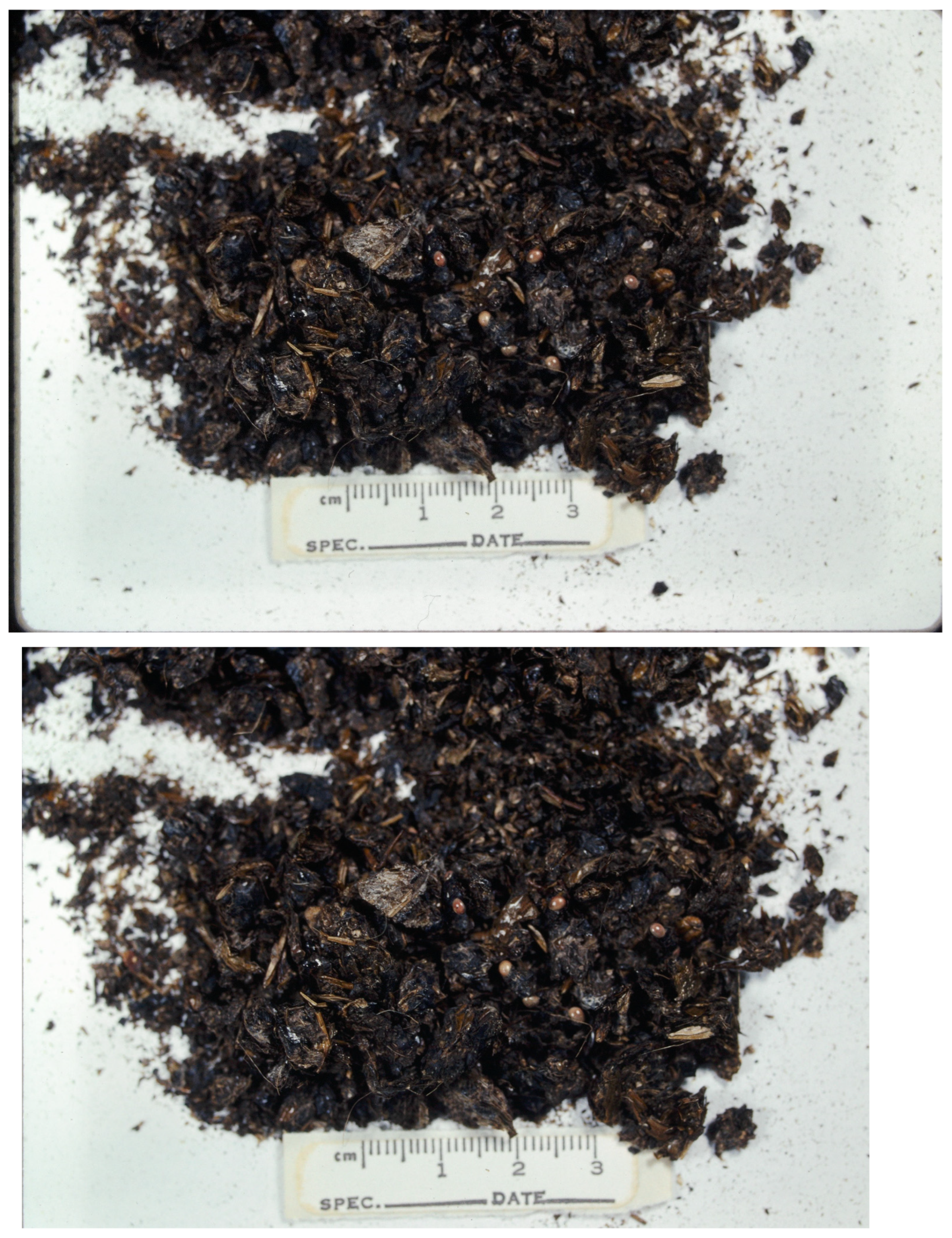

2.2. Food Item Use by Coyotes

3. Results

Food Item Use

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schmidt, K.; Ostfeld, R. Numerical and behavioral effects within a pulse-driven system: Consequences for direct and indirect interactions among shared prey. Ecology 2008, 89, 635–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.J.; Brannon, E.L. Origin and development of life history patterns in Pacific salmonids. In Salmon and Trout Migratory Behavior Symposium; Brannon, E.L., Salo, E.L., Eds.; School of Fisheries, University of Washington: Seattle, WA, USA, 1981; pp. 296–308. [Google Scholar]

- Groot, C. Pacific Salmon Life Histories; University of British Columbia Press: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Brittain, J.E. Biology of mayflies. Ann. Rev. Entomol. 1982, 27, 119–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, M.; Dybas, H.S. The periodical cicada problem. II. Evolution. Evolution 1966, 20, 466–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janzen, D.H. Tropical blackwater rivers, animals and mast fruiting by the Dipterocarpaceae. Biotropica 1974, 4, 69–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.S.; Smith, K.G.; Stephen, F.M. Emergence of 13-year periodical cicadas (Cicadidae: Magicicada): Phenology, mortality, and predator satiation. Ecology 1993, 74, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, L.M.; Leighton, M. Vertebrate responses to spatiotemporal variation in seed production of mast-fruiting Dipterocarpaceae. Ecol. Mono. 2000, 70, 101–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, R.D. Theoretical perspectives on resource pulses. Ecology 2008, 89, 671–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolff, J.O. Population fluctuations of mast-eating rodents are correlated with production of acorns. J. Mammal. 1996, 77, 850–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haney, J.C. Numerical response of birds to an irruption of elm spanworm (Ennomos subsignarius [Hbn.]; Geometridae: Lepidoptera) in old-growth forest of the Appalachian Plateau, USA. For. Ecol. Manag. 1999, 120, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.H. Periodical cicadas as resource pulses in North American forests. Science 2004, 306, 1565–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kritsky, G. The Pilgrims’ Promise: The 2025 Emergence of Periodical Cicada BROOD XIV; Ohio Biological Survey: Columbus, OH, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Dybas, H.S.; Davis, D.D. A population census of seventeen-year periodical cicadas (Homoptera: Cicadidae: Magicicada). Ecology 1962, 43, 432–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.J.; Chippendale, G.M. Nature and fate of the nutrient reserves of the periodical (17 year) cicada. J. Insect Physiol. 1973, 19, 607–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steward, V.B.; Smith, K.G.; Stephen, F.M. Red-winged blackbird predation on periodical cicadas: Bird behavior and cicada responses. Oecologia 1988, 76, 348–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storm, J.L.; Whitaker, J.O. Food habits of mammals during and emergence of 17-year cicadas (Hemiperta: Cicadidae: Magicicada spp.). Proc. Indiana Acad. Sci. 2007, 116, 196–199. [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt, C.L. The Periodical Cicada; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Bureau of Entomology: Washington, DC, USA, 1907; Available online: https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/109956 (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Getman-Pickering, Z.L.; Soltis, G.J.; Shamash, S.; Gruner, D.S.; Weiss, M.R.; Lill, J.T. Periodical cicadas disrupt trophic dynamics through community-level shifts in avian foraging. Science 2023, 382, 320–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahus, S.C.; Smith, K.G. Food habits of Blarina, Peromyscus, and Microtus in relation to an emergence of periodical cicadas (Magicicada). J. Mammal. 1990, 71, 249–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcello, G.J.; Wilder, S.M.; Meikle, D.B. Population dynamics of a generalist rodent in relation to variability in pulsed food resources in a fragmented landscape. J. Anim. Ecol. 2008, 77, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cypher, B.L. Coyote Foraging Dynamics, Space Use, and Activity Relative to Resource Variation at Crab Orchard National Wildlife Refuge, Illinois. Ph.D. Thesis, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, IL, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Fehrenbacher, J.B. Soil survey and laboratory data for some soils of Illinois. In Soil Survey Investigation No. 19; Soil Conservation Service., U.S. Department of Agriculture: Washinton, DC, USA, 1968; pp. 154–157. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Climate Data. Carbondale, IL. 2025. Available online: https://www.usclimatedata.com/climate/carbondale/illinois/united-states/usil0185 (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Braun, E.L. Deciduous Forests of Eastern North America; Blakiston: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Green, J.S.; Flinders, J.T. Diameter and pH comparisons of coyote and red fox scats. J. Wildl. Manag. 1981, 45, 765–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danner, D.A.; Dodd, N. Comparison of coyote and gray fox scat diameters. J. Wildl. Manag. 1982, 46, 240–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stains, H.J. Field key to guard hairs of middle western furbearers. J. Wildl. Manag. 1958, 38, 913–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adorjan, A.S.; Kolenosky, G.B. A Manual for the Identification of Hairs of Selected Ontario Mammals; Research Report (Wildlife) No. 90; Ontario Department of Lands and Forests: Toronto, ON, Canada, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, T.D.; Spence, L.E.; Dugnolle, C.E. Identification of the Dorsal Hairs of Some Animals of Wyoming; Wyoming Game and Fish Department: Cheyenne, WY, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Glass, B.P. Key to the Skulls of North American Mammals; Oklahoma State University: Stillwater, OK, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Roest, A.I. A Key-Guide to Mammal Skulls and Lower Jaws; Mad River Press: Eureka, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Young, J.A.; Young, C.G. Seeds of Woody Plants in North America; Dioscorides Press: Portland, OR, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Gotelli, N.J.; Ellison, A.M. A Primer of Ecological Statistics; Sinauer Associates, Inc.: Sunderland, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Brower, J.E.; Zar, J.H. Field and Laboratory Methods for General Ecology; Wm. C. Brown Publishers: Dubuque, IA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Pianka, E.R. The structure of lizard communities. Ann. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1973, 4, 53–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voigt, D.R.; Berg, W.E. Coyote. In Wild Furbearer Management and Conservation in North America; Novak, M., Baker, J.A., Obbard, M.E., Malloch, B., Eds.; Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources: Toronto, ON, Canada, 1987; pp. 344–357. [Google Scholar]

- Bekoff, M.; Gese, E.M. Coyotes. In Wild Mammals of North America: Biology, Management, and Conservation, 2nd ed.; Feldhamer, G.A., Thompson, B.C., Chapman, J.A., Eds.; The Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2003; pp. 467–481. [Google Scholar]

- Pulliam, H.R. On the theory of optimal diets. Am. Nat. 1974, 108, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyke, G.H.; Pulliam, H.R.; Charnov, E.L. Optimal foraging: A selective review of theory and tests. Quart. Rev. Biol. 1977, 52, 137–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, S.P.; French, M.G.; Knight, R.R. Grizzly bear use of army cutworm moths in the Yellowstone ecosystem. In Bears. Their Biology and Management: Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference on Bear Research and Management; Claar, J., Schullery, P., Eds.; Bear Biology Association, University of Tennessee: Knoxville, TN, USA, 1994; pp. 389–399. [Google Scholar]

- White, D., Jr.; Kendall, K.C.; Picton, H.D. Grizzly bear feeding activity at alpine army cutworm moth aggregation sites in northwest Montana. Can. J. Zool. 1998, 76, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinzer, W.P.; Ueckert, D.N.; Flinders, J.T. Food niche of coyotes in the Rolling Plains of Texas. Rangel. Ecol. Manag. J. Range Manag. Arch. 1975, 28, 22–27. [Google Scholar]

- Brillhart, D.E.; Kaufman, D.W. Spatial and seasonal variation in prey use by coyotes in north-central Kansas. Southwest. Nat. 1995, 40, 160–166. [Google Scholar]

- Whiles, M.R.; MacCallaham, J.R.; Meyer, C.K.; Brock, B.L.; Charlton, R.E. Emergence of periodical cicadas (Magicicada cassini) from a Kansas riparian forest: Densities, biomass and nitrogen flux. Am. Midl. Nat. 2001, 145, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Way, J.G. Eastern coyotes, Canis latrans, observed feeding on periodical cicadas, Magicicada septendecim. Can. Field-Nat. 2008, 122, 271–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, C.H.; Pelton, M.R. Food habits of gray foxes (Urocyon cinereoargenteus) and red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) in east Tennessee. J. Tenn. Acad. Sci. 1991, 66, 79–84. [Google Scholar]

- Cypher, B.L. Foxes. In Wild Mammals of North America: Biology, Management, and Conservation, 2nd ed.; Feldhamer, G.A., Thompson, B.C., Chapman, J.A., Eds.; The Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2003; pp. 511–546. [Google Scholar]

| Frequency of Occurrence (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food Items | 1986 (n = 102) | 1987 (n = 80) | 1988 (n = 94) | 1986–1988 (n = 276) | 1989 (n = 71) |

| White-tailed deer—adult | 23.5 | 11.3 | 18.1 | 18.1 | 1.4 |

| White-tailed deer—fawn | 16.7 | 7.5 | 13.8 | 13.0 | 7.0 |

| Cottontail | 34.3 | 32.5 | 57.4 | 41.7 | 25.4 |

| Woodchuck | 2.9 | 12.5 | 14.9 | 9.8 | 5.6 |

| Muskrat | 5.9 | 8.8 | 6.4 | 6.9 | 1.4 |

| Beaver | 0 | 1.3 | 0 | 0.4 | 0 |

| Fox squirrel | 4.9 | 1.3 | 4.3 | 3.6 | 4.2 |

| Raccoon | 5.9 | 2.5 | 9.6 | 6.2 | 2.8 |

| Prairie vole | 52.0 | 45.0 | 4.3 | 33.7 | 0 |

| Southern bog lemming | 9.8 | 11.3 | 0 | 6.9 | 0 |

| White-footed mouse | 0 | 0 | 1.1 | 0.4 | 0 |

| Cow | 1.0 | 0 | 1.1 | 0.7 | 0 |

| Canada goose | 3.9 | 3.8 | 1.1 | 2.9 | 1.4 |

| Eastern meadowlark | 2.0 | 0 | 0 | 0.7 | 0 |

| Unknown bird | 1.0 | 1.3 | 0 | 0.7 | 0 |

| Bird eggshell | 2.0 | 2.5 | 9.6 | 4.7 | 0 |

| Unidentified snake | 2.9 | 0 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 0 |

| Reptile eggshell | 2.9 | 1.3 | 5.3 | 3.3 | 0 |

| June beetle | 1.0 | 2.5 | 6.4 | 3.3 | 5.6 |

| Grasshopper | 0 | 2.5 | 0 | 0.7 | 0 |

| Cicada | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 85.9 |

| Unidentified insect | 0 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 0.7 | 0 |

| American plum | 0 | 5.0 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 0 |

| Blackberry | 0 | 0 | 4.3 | 1.4 | 0 |

| Corn | 0 | 0 | 2.1 | 0.7 | 0 |

| Unidentified fruit | 0 | 0 | 1.1 | 0.4 | 0 |

| Frequency of Occurrence (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

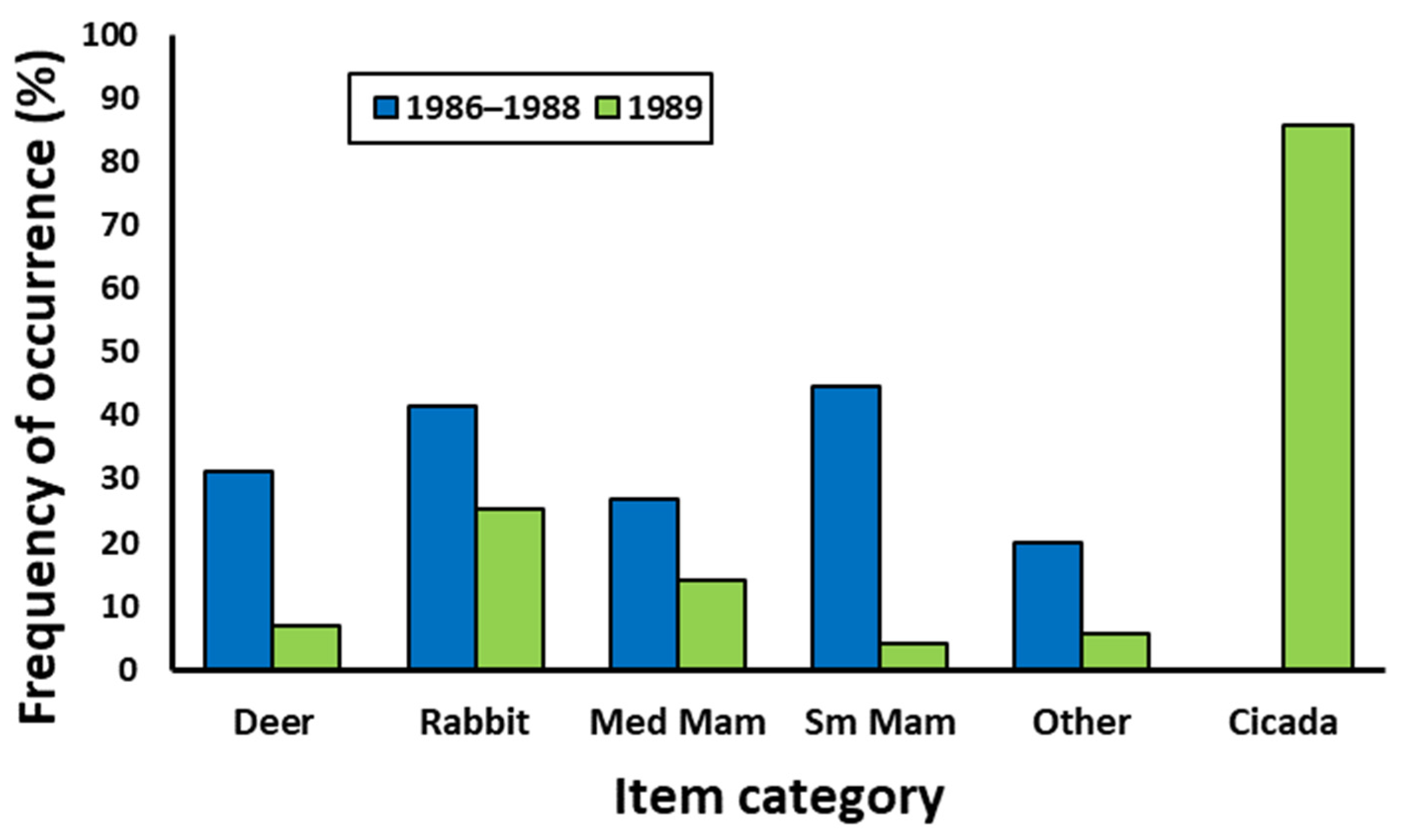

| 1986 | 1987 | 1988 | 1986–1988 | 1989 | 1986–1988 vs. 1989 | ||

| Category | (n = 102) | (n = 80) | (n = 94) | (n = 276) | (n = 71) | χ2 | p |

| White-tailed deer | 40.2 | 18.8 | 31.9 | 31.2 | 7.0 | 15.75 | <0.001 |

| Rabbit | 34.3 | 32.5 | 57.4 | 41.7 | 25.4 | 5.69 | 0.017 |

| Medium mammal | 19.6 | 26.3 | 35.1 | 26.8 | 14.1 | 4.32 | 0.038 |

| Small mammal | 61.8 | 56.3 | 5.3 | 44.6 | 4.2 | 38.01 | <0.001 |

| Other | 16.7 | 20.0 | 34.0 | 19.9 | 5.6 | 7.19 | 0.004 |

| Cicada | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 85.9 | 281.8 | <0.001 |

| H’ | 1.50 | 1.52 | 1.46 | 1.57 | 1.24 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cypher, B.L. Response of an Apex Mammalian Predator to an Emergence of 13-Year Periodical Cicadas. Animals 2026, 16, 454. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16030454

Cypher BL. Response of an Apex Mammalian Predator to an Emergence of 13-Year Periodical Cicadas. Animals. 2026; 16(3):454. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16030454

Chicago/Turabian StyleCypher, Brian L. 2026. "Response of an Apex Mammalian Predator to an Emergence of 13-Year Periodical Cicadas" Animals 16, no. 3: 454. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16030454

APA StyleCypher, B. L. (2026). Response of an Apex Mammalian Predator to an Emergence of 13-Year Periodical Cicadas. Animals, 16(3), 454. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16030454