1. Introduction

The behavior of individual animals reflects both internal states and external context [

1]. For captive animals, their early experiences contribute to later behavior which can also be shaped by the way in which they are housed. When highly intelligent and social animals such as chimpanzees (

Pan troglodytes) are kept in captivity, it is essential that their needs are met in order to provide good welfare. Research has shown that behaviors classed as abnormal, including coprophagy and regurgitation/reingestion, are present in all captive chimpanzee groups regardless of size or composition [

2], although higher rates of these behaviors are reported for chimpanzees living in pairs compared to small groups of three to seven individuals [

3], and apathy and rocking are more prevalent in hand-reared chimpanzees [

4]. Such findings can be related to social deprivation in early life [

5]. In such a cognitively and socially sophisticated species, the company of conspecifics is paramount [

6]. Yet, there is little research on how much the group size of captive chimpanzees matters. In the US, both the National Institutes of Health [

7] and the Association of Zoos and Aquariums [

8] recommend a group size of at least seven or eight individuals, preferably mimicking the wild social structure of multi-male, multi-female, age-diverse composition; while European guidelines do not specify a particular number of individuals but recommend keeping more than one adult male with several adult females and their offspring [

9]. However, it has been argued that trying to recreate such natural conditions may not be necessary because captive chimpanzees are not faced with the same pressures as their wild counterparts and zoos need to be able to consider other issues such as allowing sufficient physical space per individual and mitigating potential intra-group aggression [

10]. Nevertheless, these authors did find that chimpanzees living in groups of at least seven displayed the most locomotion and the most affiliation. The vast body of welfare research also points to the size and features of enclosures being important [see 6 for review], yet a systematic way for practitioners to quantitatively rank enclosure quality has only recently emerged [

11]. Regardless of other worthy features in a captive chimpanzee’s environment, the presence of other chimpanzees should be the priority [

12].

The fission-fusion social system of chimpanzees in the wild is well documented [

13], with individuals moving around their home ranges in dynamic and fluctuating temporary associations, parties or sub-groups, with a median party size of about four individuals [

14]. Females typically emigrate from their natal communities, whereas males only rarely move [

15,

16]. This norm of free-living chimpanzee social structure contrasts strongly with the conditions of captivity, where all members of the group are always present.

The compatibility of different individuals formed into captive groups can vary greatly, and assessment of personality should be taken into consideration. The field of animal personality has burgeoned over recent years and, although still contested in terms of definitions and methods, can be largely regarded as a temporally stable and situationally consistent way of behaving; see, e.g., [

17,

18]. Personality traits of individual chimpanzees, for example, are found to relate to observed behavior over a period of 25 years [

19]. According to evolutionary personality psychology, observed behavior is the result of interaction between evolved psychological mechanisms and the environmental conditions which activate them differentially among individuals [

20,

21]. Behavior cannot be seen as reflecting purely environmental context; it has to involve organismic mechanisms; in other words, information processing devices have adapted over time to consider sensory input and deploy appropriate overt responses. Thus, while these psychological mechanisms are consistent over time, overt behavior is context dependent. Situational factors such as the way in which animals are grouped and housed therefore have an important role to play in the determination of behavior. The expression of personality in chimpanzees also varies depending on whether they are housed in a group, individually or paired; for example, chimpanzees living in large groups rate higher on items including playful, gentle, protective, intelligent, sociable and curious [

22]. Here, I turn to the examination of the effects of grouping and rearing on indices of social competence.

Another important aspect to consider is the animal’s background. How an animal experiences its early social environment can have profound effects on the ontogeny of social competence later in life [

23,

24]. Social competence, referring to the ability to optimally express social behavior [

25], requires an animal to be able to process social information and respond appropriately. The environment in which chimpanzees are reared strongly impacts their behavior as an adult; see, e.g., [

26,

27]. Wild-born male chimpanzees groom less than captive-born individuals and this distinction took precedence over any shorter-term changes in behavior in response to changes in group composition [

28]. Similarly, such changes to current group composition, including the introduction of new members, are also found not to disturb the stability and cohesiveness of the group social network [

29]. Such findings may attest to the benefits of group-living in terms of carrying individuals through significant life events. Nevertheless, whether or not captive chimpanzees were hand-reared negatively affects their health, stress, and subjective wellbeing [

30] and affects the expression of their personality, with hand-reared individuals rated higher on Effective, Protective and Eccentric [

22]. Interestingly, Clay et al. [

30] did not find that the increased human exposure of hand-rearing affected how chimpanzees behaved socially with each other, and Martin [

31] found no differences in personality traits in differentially reared chimpanzees, but did find that raters found it harder to rate non-mother-reared individuals, possibly due to a less consistent presentation of personality traits, or to the different relationships these individuals had with the human keepers.

The importance of maternal care in the development of young has been demonstrated across a wide range of taxa; see, e.g., [

32,

33]. The presence of the mother chimpanzee in rearing and teaching her young has been emphasized continually in primatology; see, e.g., [

13,

34]. As with humans, the mother is the first playmate and, from play, an entire developmental trajectory is set [

35]. Bonds between mothers and offspring extend beyond weaning [

36] and maternal deprivation is likely to result in negative outcomes including anxiety and depression [

37] and difficulties with social integration [

38].

It is likely also that factors including grouping and rearing could interact to affect individual chimpanzees in different ways; for example, differences in the personality traits of chimpanzees that were mother-reared compared to hand-reared were more pronounced when those individuals were housed in large groups [

22]. Other individual differences such as age and sex are also important and may moderate the effects of rearing [

39]; for example, the link between hand-rearing and eccentricity was more pronounced in female chimpanzees [

22].

The development of social competence is poorly understood and most research has experimentally manipulated the early environment of species such as fish [

23] and birds [

24]. This study compares the behaviors of chimpanzees who have experienced hand-rearing compared to being reared by their mothers. It also takes into account the current social structure of the individual chimpanzees, specifically comparing those residing in groups versus in pairs or trios. The behaviors reported here include associations and responsibility for proximity, grooming, aggression and play. I predicted that there would be differences in behaviors of hand-reared and mother-reared chimpanzees, and between those housed in groups compared to pairs or trios. Intuitively, it would be expected that mother-reared and group-living chimpanzees would exhibit higher rates of sociability compared to those who had experienced hand-rearing and those not housed as part of a group. It is also predicted that hand-reared chimpanzees would show more sociable behaviors, indicating greater social competence, when residing in a large group compared to their counterparts in pairs or trios.

4. Discussion

I found clear differences in chimpanzee social behavior reflecting how individuals were grouped and reared, thus giving support to the hypotheses. Chimpanzees residing in larger groups had higher Grooming and Play scores, gave and received more frequent grooming, played more, and took more responsibility for play. Those in smaller groups groomed for longer durations with fewer partners, had higher Sociability scores due to higher median association times spread amongst a higher percentage of significant partners, spent more time alone and displayed more. Like some, but not all, previous studies [

23,

24], the chimpanzees in this study showed differences in social competence related to their rearing. Mother-reared chimpanzees took more responsibility in soliciting grooming than hand-reared apes.

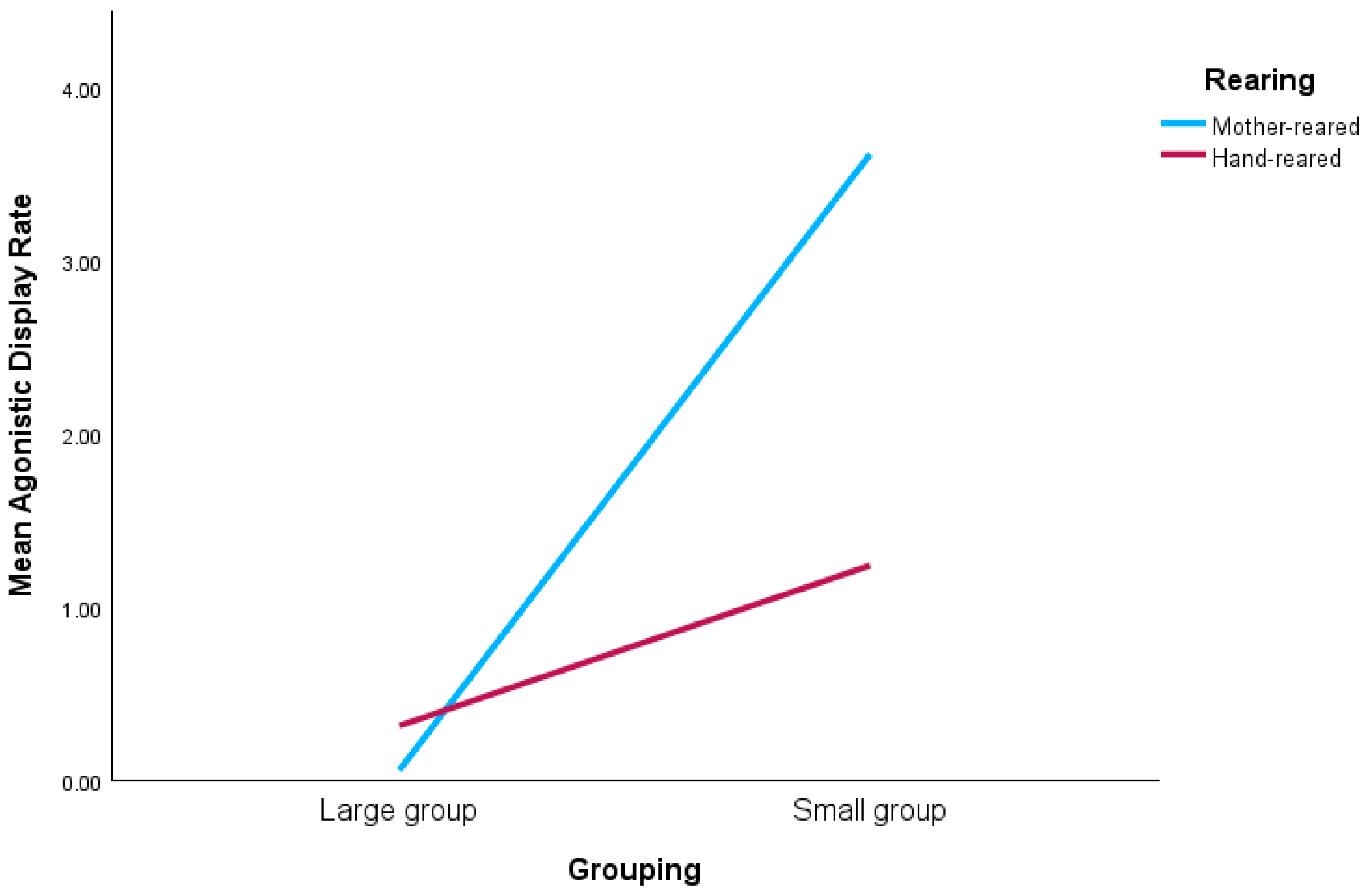

In addition, there were interactions between grouping and rearing on chimpanzee social behavior. Individuals in small groups engaged in agonistic displays more frequently than those in larger groups and mother-reared chimpanzees displayed more than hand-reared individuals. Interactions between grouping and rearing on agonistic display rate show specifically that mother- and hand-reared chimpanzees displayed more when they were housed in small groups compared to when housed in larger groups.

Chimpanzees living in larger groups can arguably be said to lead richer lives. Specifically, when compared to their conspecifics residing in pairs or trios, they engage in more frequent play and grooming, and are responsible for initiating more of these interactions. They have lower agonistic display rates when compared to those in pairs or trios, whose actions could be taken as a sign of frustration or boredom. Although they spend less time alone, they also have lower median association times and fewer significant partners. This reflects the opportunity for those in larger groups to distribute interactions across a higher number of other partners rather than having to spend disproportionate amounts of time with only one or two others. Analyses of variance on the personality ratings of these chimpanzees have already identified group size as influencing ratings on adjectives such as ‘Sociable’ and ‘Popular’ [

22]. Here, group size is found to affect median association time, a measure which could be predicted, somewhat counter-intuitively, to correlate inversely with ‘Sociable’ and ‘Popular’ ratings. That is, individuals with lower association times (because of their larger groupings) spread themselves among, or are sought out by, a greater number of partners. Therefore, ‘association’ cannot be said to measure systematically or necessarily ‘sociability’ per se, as is commonly held; see, e.g., [

13]. A more sociable ape tends to spend less time with each partner, but only because there are more partners available. Totaling time spent in association regardless of with which particular partner, and comparing that with the amount of time spent alone could, however, yield a broader measure of sociability. Even this is problematic, however, in the sense that ‘sociable’ chimpanzees were not found to spend significantly less time alone than less sociable ones, even though chimpanzees rated higher on the term ‘solitary’ do spend more time alone [

16].

By examining the top three partners with whom each subject spent the greatest amount of time there is evidence that, within a larger group, individuals tend to cluster [

44]. Within the group at Zoo A, for example, two principal clusters of associating individuals existed. One cluster comprised purely adults, being the four adult males along with four adult females, two of whom had daughters between four and five years old. The second cluster of individuals was made up of the related mothers and their mainly ventral infants, together with their older offspring. Associating with individuals in both of these clusters were three ‘floating’ immatures. They were attached to their mothers in the first cluster and to other favored partners, mainly other immatures, in the second cluster. A final trio of ‘floaters’ existed, comprising the other mother with her ventral infant and the two eldest females.

Chimpanzees in smaller groups (but still ≥ seven) at Zoos B and C, however, had more evenly distributed association patterns among group members. Those individuals housed in pairs and trios obviously had very different association patterns. Favorite partners frequently existed and, consequently in trios, another individual became an ‘outsider’. It is notable that one third of the nine chimpanzees housed in trios at Zoo C were never seen to engage in grooming activity, making them the only chimpanzees not to groom at all when at least two other partners were available. By contrast, chimpanzees in larger groups were much more likely to spend greater amounts of time engaged in grooming. Reciprocity in grooming can be seen to involve four directions: A grooms B, B grooms A, A is groomed by B, and B is groomed by A. Totally reciprocal grooming relationships (regarding top partners) often involve related individuals, particularly mothers and their offspring, which concurs with findings in wild apes [

13,

45].

Agonistic displays are a prominent feature in the lives of chimpanzees. What elicits the display can be hard to determine but it is largely driven by status acquisition and reinforcement [

46,

47]. While such displays and acts of overt aggression are often directed at one or more specific others, they are frequently general, being directed at no obvious target. Frustration, boredom, monotony, lack of variety and the anthropomorphic ‘clash of personalities’ are likely to be major factors contributing to the aggressive and display behavior of those chimpanzees housed in trios and pairs in neighboring enclosures at Zoo C. These males and certain females had relatively high display rates, often directed at other males and females able to be seen, but not physically contacted. While the presence of several males in a captive group of chimpanzees may facilitate the expression of species-typical behaviors such as displays, the present findings do not point to a significant difference between the display rates of the dominant male in the multi-male group and the single male in the other large group. Other studies have found lower rates in single males, and attribute this to a lack of motivation for assertion [

48]. However, the presence of several males is likely to provide more choice of preferred social partners for these males, and is a more natural social context.

The relative lack of play among the chimpanzees at Zoo C is striking compared to the play patterns of the individuals at the other zoos. That this lack or indeed absence of play is related to being housed in small groups and likely having experienced hand-rearing confirms previous findings of the importance of the mother’s influence on the expression of social behaviors [

34] and specifically, in fostering play while young [

13,

35]. Immatures are arguably the most popular play partners of both adults and other immatures to the extent that, without the presence of youngsters to provide the impetus for play, adult chimpanzees grouped together did not engage in this activity at all. This concurs with Bloomsmith’s [

49] finding that captive adult male chimpanzees are attracted to immatures, and they may be more likely to develop affiliative relationships with infants and juveniles because of an increase in the social complexity of captive group life. It provides some evidence for the much-debated suggestion that youngsters are essential in chimpanzee groups to optimize welfare; however, see [

50]. Indeed, building on a recent suggestion that play may be a luxury that nonhuman animals can only afford in times of high-quality food abundance and that engaging in play may be a necessary ‘hidden cost’ for wild chimpanzee mothers [

51], it could be expected that captive chimpanzees would engage in more consistent amounts of play due to their lack of uncertainty over energy expenditure in foraging.

Such findings therefore have important implications for the housing of apes in captivity. It is also worth noting the importance of the choice of measure. Here, both frequencies and durations were recorded. Median grooming was higher in small groups while rate of grooming was higher in large groups. This can be explained in terms of the number of available partners in the group but it also illustrates how the decision to use just one of these measures could impact and bias the results of a study. This consideration may not necessarily apply to all forms of social behavior. For example, both median and rate of play were higher in large than small groups. A limitation of this study is that other factors could potentially influence social behavior; for example, differences in the size and contents of the enclosures and differences in husbandry. However, the findings are important in helping zoo managers and keepers maximize the welfare of captive chimpanzees by emphasizing the need to take into account the importance of chimpanzees’ early experience and how that can act alone, and in combination with other factors, including age and sex, and the size of the group in which they live, in determining their trajectory within a captive group.

Being housed with conspecifics from all age-sex classes not only enables individuals to learn from each other, but permits choice of preferred social partners. In situations where, for some reason, chimpanzees are kept in pairs or trios, it is vital that the individuals are chosen carefully. They will likely (be forced to) spend disproportionately large amounts of time with only one or two other conspecifics. It need not be that the chimpanzees are wholly similar in terms of their personality [

22] or behavior, because matching a mother-reared chimpanzee with a hand-reared one could facilitate a bond due to the former being more likely to take more responsibility to solicit grooming. That mother-reared chimpanzees have the social competence needed to approach others and solicit grooming is an important finding. Arguably, most animal mothers would wish their offspring to be competent and confident in life and, indeed, I have shown here that hand-reared individuals likely lack this confidence as they do not take the responsibility to ask for grooming from their conspecifics. It is akin to the shy child sitting on the friendship bench waiting to be approached. On the other hand, both mother-reared and hand-reared chimpanzees perform agonistic displays more frequently when housed in a smaller group (compared to large), and so attention needs to be paid to the wider surroundings of chimpanzees housed in pairs or trios, as displaying due to the presence of nearby but out-of-reach conspecifics could be mitigated. This supports other calls for zoos to consider issues such as allowing sufficient physical space per individual to mitigate potential aggression [

10].