Adding a Yeast Blend to the Diet of Holstein Females Minimizes the Negative Impacts of Ingesting Feed Naturally Contaminated with Aflatoxin B1

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Facilities, Animals, and Diet

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Data and Sample Collection

2.4. Laboratory Analyses

2.4.1. Feed Analyses and Measurement of Mycotoxins in Feed

2.4.2. Hematological and Biochemical Analyses

2.4.3. Oxidative Status

2.4.4. Immunological Markers

2.4.5. Volatile Fatty Acid Profile in the Rumen

2.4.6. pH and Protozoan Count in Ruminal Fluid

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Performance

3.2. Complete Blood Count

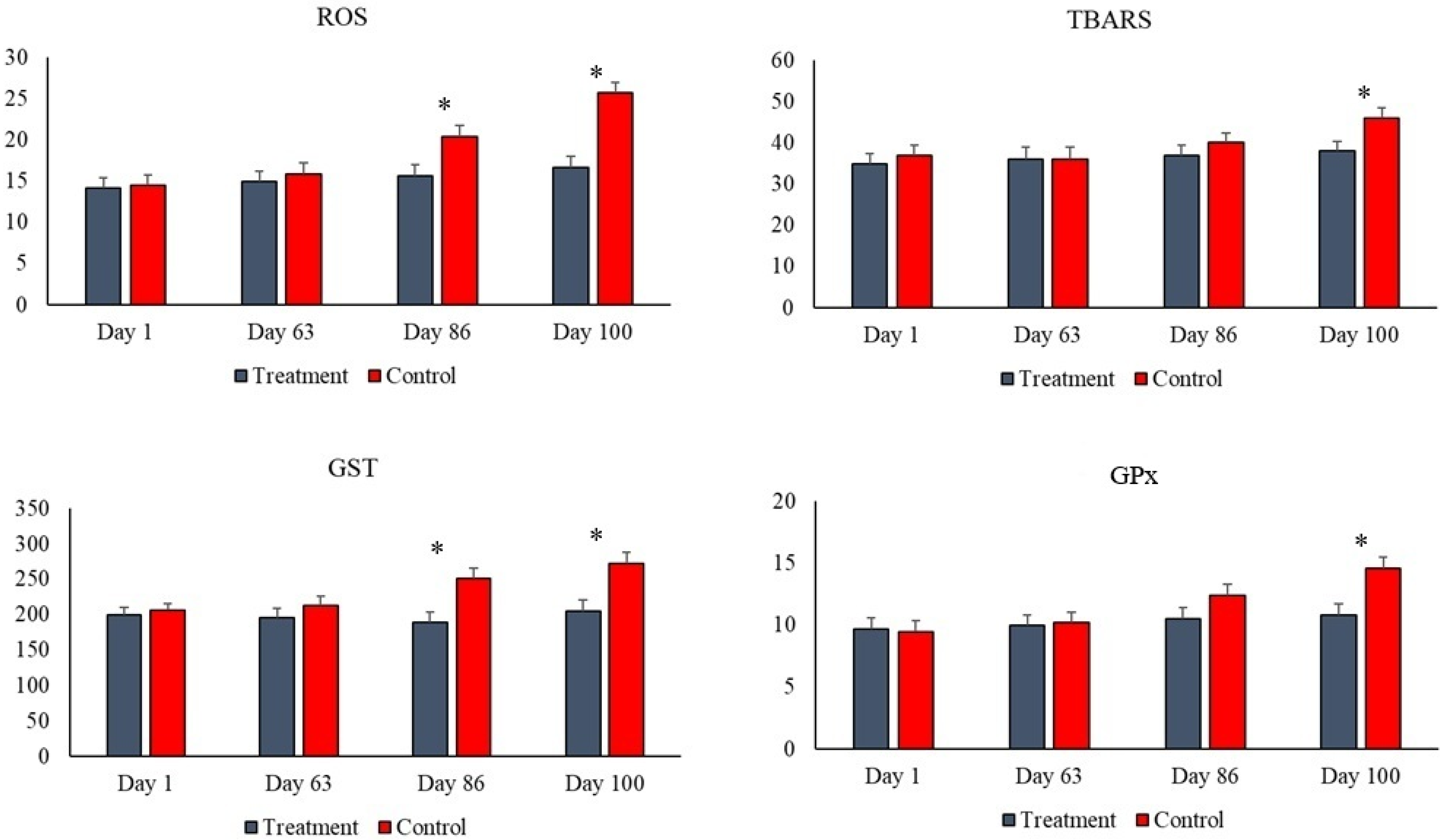

3.3. Serum and Oxidative Biochemistry

3.4. Immunological Markers

3.5. pH, Protozoa, and Volatile Fatty Acid Profile in Rumen Fluid

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baker, L.M.; Kraft, J.; Karnezos, T.P.; Greenwood, S.L. The effects of dietary yeast and yeast-derived extracts on rumen microbiota and their function. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2022, 294, 115476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wen, H.; Wan, H.; Wu, H.; Chen, Y.; Li, S.; Zhang, L.; Sun, X.; Li, B.; et al. Yeast Probiotic and Yeast Products in Enhancing Livestock Feeds Utilization and Performance: An Overview. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estima-Silva, P.; Chaucheyras-Durand, F.; Cunha, A.R.; Souza, H.F.; Pereira, K.N.; Oliveira, A.C.D.; da Silva, S.M.C.; de Oliveira, A.M.M.S.; de Macedo Júnior, G.L.; Conrad, N.L. Effect of Saccharomyces cerevisiae in a culture or lysate on innate immunity, ruminal and intestinal morphology of feedlot-finished steers. Semin. Ciências Agrárias 2020, 41, 201–216. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, N.; Wu, W.; Pan, J.; Long, M. Detoxification Strategies for Zearalenone Using Microorganisms: A Review. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yiannikouris, A.; Jouany, J.P. Mycotoxins in feeds and their fate in animals: A review. Anim. Res. 2002, 51, 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Wu, X.; Duan, J.; Huang, P.; Li, T.; Yin, Y.; Yin, J. Low-protein diets supplemented with glutamic acid or aspartic acid ameliorate intestinal damage in weaned piglets challenged with hydrogen peroxide. Anim. Nutr. 2021, 7, 356–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadpoor, M.; Peeters, C.; Henricks, P.A.J.; Varasteh, S.; Pieters, R.J.; Folkerts, G.; Braber, S. Anti-Pathogenic Functions of Non-Digestible Oligosaccharides In Vitro. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdick Sanchez, N.C.; Broadway, P.R.; Carroll, J.A. Influence of Yeast Products on Modulating Metabolism and Immunity in Cattle and Swine. Animals 2021, 11, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yiannikouris, A.; Poughon, L.; Cameleyre, X.; Dussap, C.-G.; François, J.; Bertin, G.; Jouany, J.-P. A novel technique to evaluate interactions between Saccharomyces cerevisiae cell wall and mycotoxins: Application to zearalenone. Biotechnol. Lett. 2003, 25, 783–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiannikouris, A.; Apajalahti, J.; Siikanen, O.; Dillon, G.P.; Moran, C.A. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Cell Wall-Based Adsorbent Reduces Aflatoxin B1 Absorption in Rats. Toxins 2021, 13, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korosteleva, S.N.; Smith, T.K.; Boermans, H.J. Effects of feedborne Fusarium mycotoxins on the performance, metabolism, and immunity of dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2007, 90, 3867–3873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kholif, A.E.; Anele, A.A.; Anele, U.Y. Microbial feed additives in ruminant feeding: Effects on ruminal fermentation, microbial balance, and animal performance. AIMS Microbiol. 2024, 10, 542–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, T.L.; Favaretto, J.A.R.; Brunetto, A.L.R.; Zatti, E.; Marchiori, M.S.; Pereira, W.A.B.; Bajay, M.M.; Da Silva, A.S. Dietary Additive Combination for Dairy Calves After Weaning Has a Modulating Effect on the Profile of Short-Chain Fatty Acids in the Rumen and Fecal Microbiota. Fermentation 2024, 10, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Meng, L.; Liu, H.; Wang, J.; Zheng, N. The Compromised Intestinal Barrier Induced by Mycotoxins. Toxins 2020, 12, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, R.; Kiarie, E.G.; Yiannikouris, A.; Sun, L.; Karrow, N.A. Nutritional impact of mycotoxins in food animal production and strategies for mitigation. J Animal Sci Biotechnol 2022, 13, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Applebaum, R.S.; Brackett, R.E.; Wiseman, D.W.; Marth, E.H. Aflatoxin: Toxicity to dairy cattle and occurrence in milk and milk products—A review. J. Food Prot. 1982, 45, 752–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Ogunade, I.M.; Vyas, D.; Adesogan, A.T. Aflatoxin in dairy cows: Toxicity, occurrence in feedstuffs and milk and dietary mitigation strategies. Toxins 2021, 13, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, D.; Chauhan, S.L. A review of aflatoxins in milk: Occurrence, toxicity and detection. Int. J. Veter. Sci. Anim. Husb. 2023, 8, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuste, S.; Amanzougarene, Z.; de la Fuente, G.; Fondevila, M.; de Vega, A. Effects of partial substitution of barley with maize and sugar beet pulp on growth performance, rumen fermentation and microbial diversity shift of beef calves during transition from a milk and pasture regimen to a high concentrate diet. Livest. Sci. 2020, 238, 104071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International, 16th ed.; AOAC International: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Van Soest, P.J.; Robertson, J.B.; Lewis, B.A. Methods for dietary fiber, neutral detergent fiber, and nonstarch polysaccharides in relation to animal nutrition. J. Dairy Sci. 1991, 74, 3583–3597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, L.K.F.; Silva, A.S.; Bottari, N.B.; Santurio, J.M.; Morsch, V.M.; Piva, M.M.; Mendes, R.E.; Gloria, E.M.; Paiano, D. Effects of fed mycotoxin contaminated diets supplemented with spray-dried porcine plasma on cholinergic response and behavior in piglets. An. Acad. Bras. Ciênc. 2019, 91, e20180419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, J.J.; Harvey, J.W.; Bruss, M.L. Clinical Biochemistry of Domestic Animals, 6th ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Jentzsch, A.M.; Bachmann, H.; Fürst, P.; Biesalski, H.K. Improved analysis of malondialdehyde in human body fluids. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1996, 20, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, S.F.; LeBel, C.P.; Bondy, S.C. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of reactive oxygen species in isolated mitochondria. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1992, 13, 241–246. [Google Scholar]

- Paglia, D.E.; Valentine, W.N. Studies on the quantitative and qualitative characterization of erythrocyte glutathione peroxidase. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 1967, 70, 158–169. [Google Scholar]

- Tomasi, T.; Volpato, A.; Pereira, W.A.B.; Debastiani, L.H.; Bottari, N.B.; Morsch, V.M.; Schetinger, M.R.C.; Leal, M.L.R.; Machado, G.; Silva, A.S. Metaphylactic effect of minerals on the immune response, biochemical variables and antioxidant status of newborn calves. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2018, 102, 819–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehority, B.A. Evaluation of subsampling and fixation procedures used for counting rumen protozoa. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1984, 48, 182–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunny, S.M.; Umar, A.; Bhatti, H.S.; Honey, S.F. Aflatoxin risk in the era of climatic change—A comprehensive review. CABI Agric. Biosci. 2024, 5, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadway, P.R.; Carroll, J.A.; Cole, N.A. Effects of yeast cell wall supplementation on inflammatory markers and performance of steers after transport. J. Anim. Sci. 2015, 93, 4811–4818. [Google Scholar]

- Carpinelli, N.A.; Halfen, J.; Michelotti, T.C.; Rosa, F.; Trevisi, E.; Chapman, J.D.; Sharman, E.S.; Osorio, J.S. Yeast Culture Supplementation Effects on Systemic and Polymorphonuclear Leukocytes’ mRNA Biomarkers of Inflammation and Liver Function in Peripartal Dairy Cows. Animals 2023, 13, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.G.; Coleman, G.S. The Ciliate Protozoa; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Newbold, C.J.; de la Fuente, G.; Williams, P.A.; McIlroy, S.G. The role of ciliate protozoa in the rumen: From background actors to featured role in microbiome research. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, F.; Tian, H.; Yang, H.; Deng, Q. Rumen protozoa and viruses—New insights into their diversity, function, and interactions. Anim. Nutr. 2022, 10, 442–450. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.; Wang, Z.; Yan, X.; Zhao, Y.; Tan, L.; Miao, X.; Zhao, R.; Huo, W.; Chen, L.; Li, Q.; et al. The study on the impact of indoleacetic acid on enhancing the ability of the rumen’s original microecology to degrade aflatoxin B1. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, I. A review on the effects of mycotoxins in dairy ruminants. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2014, 54, 1155–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desnoyers, M.; Giger-Reverdin, S.; Bertin, G.; Duvaux-Ponter, C.; Sauvant, D. Meta-analysis of the influence of Saccharomyces cerevisiae supplementation on ruminal parameters and milk production of ruminants. J. Dairy Sci. 2009, 92, 1620–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amin, A.B.; Mao, S. Influence of yeast on rumen fermentation, growth performance and quality of products in ruminants: A review. Anim Nutr. 2021, 7, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggiolino, A.; Centoducati, G.; Casalino, E.; Elia, G.; Latronico, T.; Liuzzi, M.G.; Macchia, L.; Dahl, G.E.; Ventriglia, G.; Zizzo, N.; et al. Use of a commercial feed supplement based on yeast products and microalgae with or without nucleotide addition in calves. J. Dairy Sci. 2023, 106, 4397–4412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volman, J.J.K.; Ramakers, J.D.; Plat, J. Dietary modulation of immune function by β-glucans. Physiol. Behav. 2008, 94, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocha, F.D.; Pereira, R.C.; Kaplan, M.A.C.; Teixeira, V.L. Produtos naturais de algas marinhas e seu potencial antioxidante. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2007, 17, 629–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedes, A.C.; Amaro, H.M.; Malcata, F.X. Microalgae as Sources of Carotenoids. Mar. Drugs 2011, 9, 625–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fesel, C.; Zuccaro, A. Strategies for the detoxification of mycotoxins. Toxins 2016, 8, 38. [Google Scholar]

- Mafe, A.N.; Nkene, I.H.; Ali, A.B.M.; Edo, G.I.; Akpoghelie, P.O.; Yousif, E.; Isoje, E.F.; Igbuku, U.A.; Ismael, S.A.; Essaghah, A.E.A.; et al. Smart probiotic solutions for mycotoxin mitigation: Innovations in food safety and sustainable agriculture. Probiotics Antimicrob. Prot. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Corn Silage | Hay | Concentrate 1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dry matter—DM (%) | 31.40 | 85.30 | 88.40 |

| Ash (% DM) | 4.98 | 6.31 | 8.65 |

| Ether extract (% DM) | 2.21 | 0.86 | 3.37 |

| Crude protein (% DM) | 4.10 | 2.97 | 17.10 |

| NDF (% DM) | 62.80 | 76.20 | 25.90 |

| ADF (% DM) | 37.10 | 31.00 | 9.76 |

| Starch (% DM) | 21.30 | - | 31.10 |

| Variables | Control (n = 3) | Treatment (n = 3) | SEM | p-Value 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight (kg) | ||||

| Initial | 163 | 168 | 6.12 | 0.85 |

| Final | 256 b | 274 a | 7.31 | 0.05 |

| ADG, kg | 0.92 b | 1.06 a | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| DMI, kg MS | 5.89 | 5.79 | 0.16 | 0.98 |

| Feed efficiency, kg/kg | 0.156 b | 0.183 a | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| Variables | Control (n = 12) | Treatment (n = 12) | SEM | p-Treat 1 | p-Day 2 | p-Treat × Day 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White blood cells (×103 µL) | 13.40 | 14.20 | 1.46 | 0.87 | 0.64 | 0.76 |

| Lymphocytes (×103 µL) | 7.68 b | 9.01 a | 1.14 | 0.05 | 0.17 | 0.06 |

| Granulocytes (×103 µL) | 4.55 | 3.98 | 0.33 | 0.46 | 0.27 | 0.52 |

| Monocytes (×103 µL) | 1.21 | 1.25 | 0.12 | 0.93 | 0.81 | 0.89 |

| Red blood cells (×106 µL) | 7.33 | 7.28 | 0.12 | 0.97 | 0.93 | 0.98 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 10.90 | 10.9 | 0.17 | 0.98 | 0.95 | 0.98 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 30.60 | 30.8 | 0.39 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.97 |

| Platelets (×103 µL) | 349 | 330 | 31.7 | 0.86 | 0.75 | 0.81 |

| Variables | Control (n = 12) | Treatment (n = 12) | SEM | p-Treat 1 | p-Day 2 | p-Treat × Day 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.04 | 2.97 | 0.05 | 0.92 | 0.74 | 0.82 |

| Globulin (g/dL) | 2.94 | 2.92 | 0.07 | 0.94 | 0.86 | 0.89 |

| Total protein (g/dL) | 5.98 | 5.90 | 0.09 | 0.96 | 0.91 | 0.93 |

| Creatine kinase (U/L) | 255 | 274 | 29.10 | 0.85 | 0.61 | 0.52 |

| Cholinesterase (U/L) | 2514 | 2462 | 88.10 | 0.56 | 0.34 | 0.29 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 71.10 | 74.90 | 2.36 | 0.77 | 0.83 | 0.81 |

| Fructosamine | 303 | 298 | 5.79 | 0.89 | 0.92 | 0.92 |

| Urea (mg/dL) | 35.40 | 34.30 | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.95 |

| IgA (mg/dL) | 9.99 | 9.88 | 0.31 | 0.87 | 0.81 | 0.84 |

| IgG (g/dL) | 3.88 | 4.08 | 0.18 | 0.38 | 0.04 | 0.05 |

| Ceruloplasmin (g/dL) | 0.83 a | 0.67 b | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.26 |

| Ferritin (g/dL) | 0.21 | 0.22 | 0.01 | 0.94 | 0.93 | 0.96 |

| Transferrin (g/dL) | 0.25 b | 0.36 a | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.11 |

| AST (U/L) | 125 a | 102 b | 5.41 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| ALT (U/L) | 12.40 a | 8.98 b | 0.84 | 0.05 | 0.13 | 0.17 |

| GGT (U/L) | 39.40 | 28.70 | 3.25 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| ROS (U fluorescence) | 21.50 a | 15.60 b | 1.35 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| TBARS (nmol/mL) | 42.60 | 37.10 | 2.45 | 0.34 | 0.05 | 0.02 |

| GST (μmol Cdnb/min) | 254 a | 195 b | 14.10 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| GPx (U/mg protein) | 12.40 | 10.10 | 0.96 | 0.42 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Variables | Control (n = 12) | Treatment (n = 12) | SEM | p-Treat 1 | p-Day 3 | p-Treat × Day 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.95 | |||

| d63 | 6.63 | 6.64 | 0.03 | |||

| d100 | 6.64 | 6.66 | 0.04 | |||

| Protozoan (×107 n°/L) | 0.75 | 0.01 | 0.01 | |||

| d63 | 64.1 | 62.5 | 3.36 | |||

| d100 | 36.1 b | 51.7 a | 3.67 | |||

| Acetic acid (mmol/L) | 0.96 | 0.98 | 0.93 | |||

| d63 | 63.2 | 63.1 | 0.36 | |||

| d100 | 65.1 | 64.3 | 0.37 | |||

| Propionic acid (mmol/L) | 0.89 | 0.79 | 0.03 | |||

| d63 | 9.6 b | 12.81 a | 0.24 | |||

| d100 | 10.5 | 12.3 | 0.31 | |||

| Butyric acid (mmol/L) | 0.91 | 0.72 | 0.94 | |||

| d63 | 8.66 | 8.76 | 0.29 | |||

| d100 | 9.02 | 9.1 | 0.3 | |||

| Isovaleric acid (mmol/L) | 0.68 | 0.19 | 0.05 | |||

| d63 | 1.71 a | 1.52 b | 0.04 | |||

| d100 | 1.64 | 1.62 | 0.03 | |||

| Valeric acid (mmol/L) | 0.86 | 0.73 | 0.89 | |||

| d63 | 1.16 | 1.03 | 0.03 | |||

| d100 | 1.11 | 1.14 | 0.03 | |||

| Total VFA (mmol/L) | 0.86 | 0.81 | 0.05 | |||

| d63 | 84.3 b | 87.2 a | 0.39 | |||

| d100 | 87.4 | 88.5 | 0.45 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Torteli, M.A.; Brunetto, A.L.R.; Mello, E.P.; Deolindo, G.L.; Nora, L.; dos Santos, T.L.; Silva, L.E.L.e.; Wagner, R.; Silva, A.S.d. Adding a Yeast Blend to the Diet of Holstein Females Minimizes the Negative Impacts of Ingesting Feed Naturally Contaminated with Aflatoxin B1. Animals 2026, 16, 219. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020219

Torteli MA, Brunetto ALR, Mello EP, Deolindo GL, Nora L, dos Santos TL, Silva LELe, Wagner R, Silva ASd. Adding a Yeast Blend to the Diet of Holstein Females Minimizes the Negative Impacts of Ingesting Feed Naturally Contaminated with Aflatoxin B1. Animals. 2026; 16(2):219. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020219

Chicago/Turabian StyleTorteli, Mario Augusto, Andrei Lucas Rebelatto Brunetto, Emeline P. Mello, Guilherme Luiz Deolindo, Luisa Nora, Tainara Letícia dos Santos, Luiz Eduardo Lobo e Silva, Roger Wagner, and Aleksandro Schafer da Silva. 2026. "Adding a Yeast Blend to the Diet of Holstein Females Minimizes the Negative Impacts of Ingesting Feed Naturally Contaminated with Aflatoxin B1" Animals 16, no. 2: 219. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020219

APA StyleTorteli, M. A., Brunetto, A. L. R., Mello, E. P., Deolindo, G. L., Nora, L., dos Santos, T. L., Silva, L. E. L. e., Wagner, R., & Silva, A. S. d. (2026). Adding a Yeast Blend to the Diet of Holstein Females Minimizes the Negative Impacts of Ingesting Feed Naturally Contaminated with Aflatoxin B1. Animals, 16(2), 219. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020219