Integrated Single-Cell and Bulk Transcriptomics Unveils Immune Profiles in Chick Erythroid Cells upon Avian Pathogenic Escherichia coli Infection

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

2.2. Animals and Experimental Groups

2.3. Sample Collection

2.4. Histopathological Analysis

2.5. RT-qPCR

2.6. Multi-Phase Transcriptomic Strategy and Experimental Design

2.6.1. scRNA-Seq Exploration

2.6.2. Bulk RNA-Seq Validation

2.6.3. RT-qPCR Quantification Phase

2.7. Single-Cell RNA Sequencing

2.7.1. Single-Cell Transcriptome Library Prep, Sequencing, and Data Analysis

2.7.2. Differential Expression, Functional Enrichment, Pseudotime, and Regulatory Network Analysis

2.8. Bulk RNA-Seq

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Pathological Manifestations in Chick Organs and Innate Immune Responses of ch-ECs Following APEC Infection

3.1.1. Pathological Manifestations in Various Organs of Chicks Infected with APEC

3.1.2. Expression of Innate Immune Response Genes in Chick Erythroid Cells

3.2. Strategy for scRNA-Seq and Data Analysis of the Chick Erythroid Cells

3.3. Immune Heterogeneity of Erythroid Cells

3.4. Transition Trajectories and Transcriptional Regulatory Network of Erythroid Cells

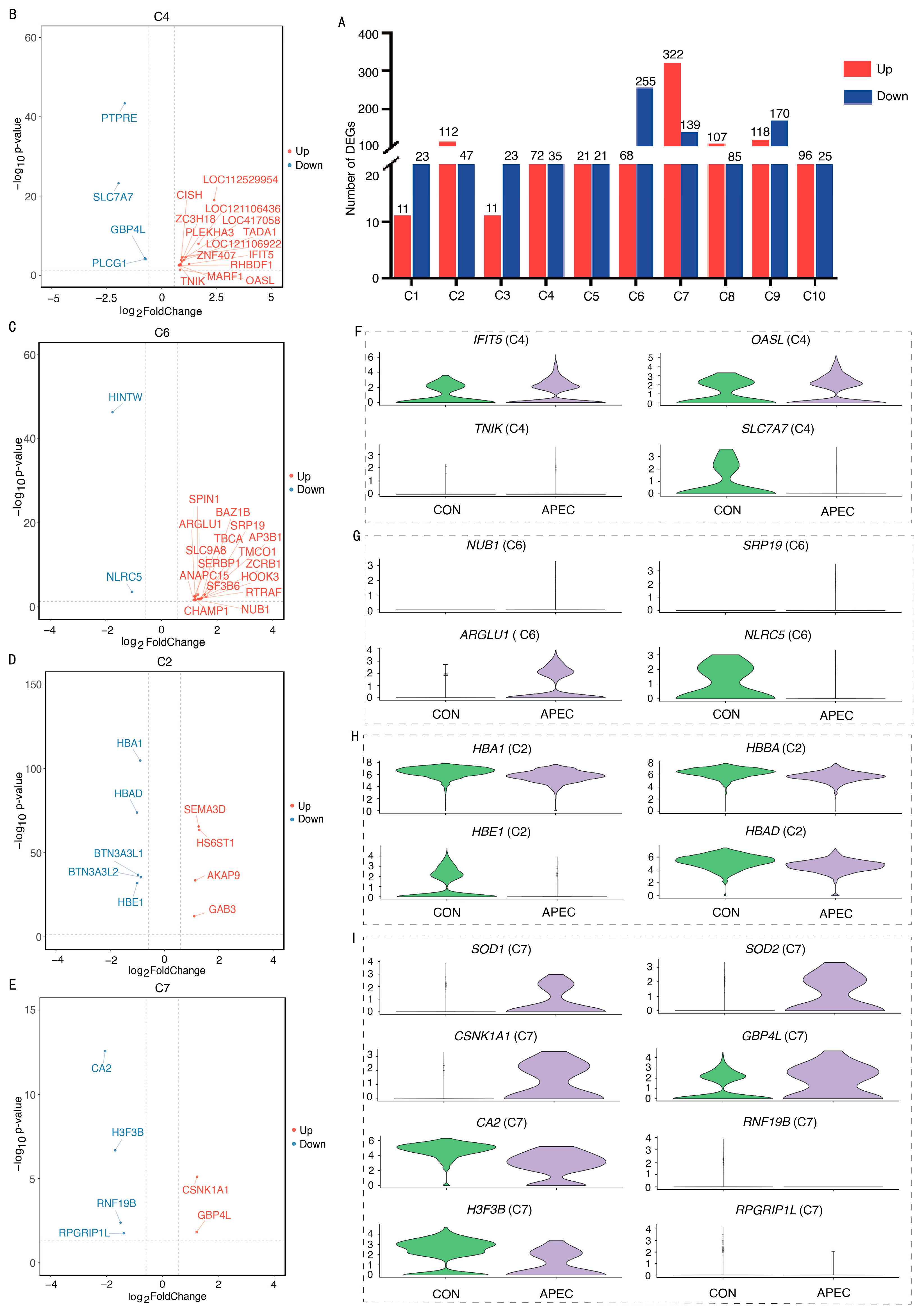

3.5. Transcriptome Analysis of Erythroid Cell Subpopulations Following APEC-Infection

3.6. Integrated Analysis of Bulk and Single-Cell RNA-Seq with RT-qPCR Validation

3.7. Immune Function Profiling in DEGs from ch-EC Subpopulations and Bulk RNA-Seq Data

4. Discussion

4.1. Immune Genes in Chick Erythroid Cells

4.2. Immune Signaling Pathways in Chick Erythroid Cells

4.3. Immune Heterogeneity of Chick Erythroid Cells

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bianconi, E.; Piovesan, A.; Facchin, F.; Beraudi, A.; Casadei, R.; Frabetti, F.; Vitale, L.; Pelleri, M.C.; Tassani, S.; Piva, F.; et al. An estimation of the number of cells in the human body. Ann. Hum. Biol. 2013, 40, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delyea, C.; Bozorgmehr, N.; Koleva, P.; Dunsmore, G.; Shahbaz, S.; Huang, V.; Elahi, S. CD71+ Erythroid Suppressor Cells Promote Fetomaternal Tolerance through Arginase-2 and PDL-1. J. Immunol. 2018, 200, 4044–4058. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, L.K.M.; Murphy, S.; Kokkinaki, D.; Venosa, A.; Sherrill-Mix, S.; Casu, C.; Rivella, S.; Weiner, A.; Park, J.; Shin, S.; et al. DNA binding to TLR9 expressed by red blood cells promotes innate immune activation and anemia. Sci. Transl. Med. 2021, 13, eabj1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.L.; Qiao, M.L.; Zhang, H.C.; Xie, C.H.; Cao, X.Y.; Zhou, J.; Yu, J.; Nie, R.H.; Meng, Z.X.; Song, R.Q.; et al. Avian pathogenic Escherichia coli alters complement gene expression in chicken erythroid cells. Br. Poult. Sci. 2025, 66, 307–314. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Chen, J.; Lu, L.; Xu, Z.; Li, F.; Yang, M.; Li, J.; Lin, L.; Qin, Z. The Antibacterial Activity of erythroid cells From Goose (Anser domesticus) Can Be Associated with Phagocytosis and Respiratory Burst Generation. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 766970. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, M.S.; Paolucci, S.; Barjesteh, N.; Wood, R.D.; Sharif, S. Chicken erythroid cells respond to Toll-like receptor ligands by up-regulating cytokine transcripts. Res. Vet. Sci. 2013, 95, 87–91. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, Y.H.; Kim, J.K. Dissecting Cellular Heterogeneity Using Single-Cell RNA Sequencing. Mol. Cells 2019, 42, 189–199. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, X.; Zhang, X. Studying temporal dynamics of single cells: Expression, lineage and regulatory networks. Biophys. Rev. 2024, 16, 57–67. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Xu, Z.; Qiu, Y.; Qiu, X.; Tan, L.; Song, C.; Sun, Y.; Liao, Y.; Liu, X.; Ding, C. Single-Cell Transcriptome Atlas of Newcastle Disease Virus in Chickens Both In Vitro and In Vivo. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e0512122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, J.; Zhu, P.; Shi, L.; Liu, Y.; Yang, X.; Yang, X. Single-nucleus transcriptome reveals cell dynamic response of liver during the late chick embryonic development. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 103979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fomukong, H.A.; Kalu, M.; Aimola, I.A.; Sallau, A.B.; Bello-Manga, H.; Gouegni, F.E.; Ameloko, J.U.; Bello, Z.K.; David, A.U.; Baba, R.S. Single-cell RNA seq analysis of erythroid cells reveals a specific sub-population of stress erythroid progenitors. Hematology 2023, 28, 2261802. [Google Scholar]

- Gimenez, G.; Kalev-Zylinska, M.L.; Morison, I.; Bohlander, S.K.; Horsfield, J.A.; Antony, J. Cohesin rad21 mutation dysregulates erythropoiesis and granulopoiesis output within the whole kidney marrow of adult zebrafish. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2025, 328, 9–19. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Z.Y.; Zhang, X.F.; Hu, Y.Z.; Zhu, M.D.; Jin, J.; Qian, P. Comparison of staining quality between rapid and routine hematoxylin and eosin staining of frozen breast tissue sections: An observational study. J. Int. Med. Res. 2024, 52, 3000605241259682. [Google Scholar]

- Amezquita, R.A.; Lun, A.T.L.; Becht, E.; Carey, V.J.; Carpp, L.N.; Geistlinger, L.; Marini, F.; Rue-Albrecht, K.; Risso, D.; Soneson, C.; et al. Orchestrating single-cell analysis with Bioconductor. Nat. Methods. 2020, 17, 137–145. [Google Scholar]

- Samour, J. Diagnostic Value of Hematology. In Clinical Avian Medicine, 1st ed.; Harrison, G., Lightfoot, T., Eds.; Spix Publishing: Palm Beach, FL, USA, 2006; pp. 587–599. [Google Scholar]

- Jahejo, A.R.; Jia, F.J.; Raza, S.H.A.; Shah, M.A.; Yin, J.J.; Ahsan, A.; Waqas, M.; Niu, S.; Ning, G.B.; Zhang, D.; et al. Screening of toll-like receptor signaling pathway-related genes and the response of recombinant glutathione S-transferase A3 protein to thiram induced apoptosis in chicken erythroid cells. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2021, 114, 103831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahejo, A.R.; Bukhari, S.A.R.; Jia, F.J.; Raza, S.H.A.; Shah, M.A.; Rajput, N.; Ahsan, A.; Niu, S.; Ning, G.B.; Zhang, D.; et al. Integration of gene expression profile data to screen and verify immune-related genes of chicken erythroid cells involved in Marek’s disease virus. Microb. Pathog. 2020, 148, 104454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Jahejo, A.R.; Qiao, M.L.; Han, X.Y.; Cheng, Q.Q.; Mangi, R.A.; Qadir, M.F.; Zhang, D.; Bi, Y.H.; Wang, Y.; et al. NF-κB pathway genes expression in chicken erythroid cells infected with avian influenza virus subtype H9N2. Br. Poult. Sci. 2021, 62, 666–671. [Google Scholar]

- Vinciguerra, G.L.; Capece, M.; Scafetta, G.; Rentsch, S.; Vecchione, A.; Lovat, F.; Croce, C.M. Role of Fra-2 in Cancer. Cell Death Differ. 2024, 31, 136–149. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Qiao, Y.; Chen, Z.; Liang, Y.; Cui, L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Xu, L.; Wei, P.; Liu, S.; et al. Fos Facilitates Gallid Alpha-Herpesvirus 1 Infection by Transcriptional Control of Host Metabolic Genes and Viral Immediate Early Gene. Viruses 2021, 13, 1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katagiri, T.; Kameda, H.; Nakano, H.; Yamazaki, S. Regulation of T cell differentiation by the AP-1 transcription factor JunB. Immunol. Med. 2021, 44, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Huang, S.; Pan, R.; Chen, X.; Liu, T.; Zhang, R.; Zhu, F.; Fang, Q.; Wu, L.; Dai, J.; et al. The PDE4DIP-AKAP9 Axis Promotes Lung Cancer Growth through Modulation of PKA Signalling. Commun. Biol. 2025, 8, 178. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, J.; Auduong, L.; White, E.S.; Yue, X. Up-regulation of heparan sulfate 6-O-sulfation in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2014, 50, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sliz, A.; Locker, K.C.S.; Lampe, K.; Godarova, A.; Plas, D.R.; Janssen, E.M.; Jones, H.; Herr, A.B.; Hoebe, K. Gab3 is required for IL-2- and IL-15-induced NK cell expansion and limits trophoblast invasion during pregnancy. Sci. Immunol. 2019, 4, eaav3866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, B.; Yu, T.; Liu, W.; Ye, S.Q.; Wang, L.X.; Yang, Y.; Gong, P.; Ran, Z.P.; Huang, H.J.; Wen, J.H. Identification of genes and pathways related to lipopolysaccharide signaling in duckling spleens. Genet. Mol. Res. 2015, 14, 17312–17321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukaj, S. Heat Shock Protein 70 as a Double Agent Acting Inside and Outside the Cell: Insights into Autoimmunity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, J.; Cui, Z. HSP40 Mediated TLR-Dorsal-AMPs Pathway in Portunus trituberculatus. Fish Shellfish. Immunol. 2023, 133, 108536. [Google Scholar]

- Hewawaduge, C.; Kwon, J.; Park, J.Y.; Lee, J.H. A low-endotoxic Salmonella enterica Gallinarum serovar delivers infectious bronchitis virus immunogens via a dual-promoter vector system that drives protective immune responses through MHC class-I and -II activation in chickens. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 103844. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.H.; Liu, Y.J.; Guo, Y.S.; Liu, C.; Yang, Y.P.; Fan, X.X.; Yang, H.L.; Liu, Y.G.; Ma, T. Function and inhibition of P38 MAP kinase signaling: Targeting multiple inflammation diseases. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2024, 220, 115973. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.; Fan, C.; Xiao, Y.; Lü, S.; Jiang, G.; Zou, M.; Wang, Y.; Guo, Q.; Che, Z.; Peng, X. Protection of Chickens from Mycoplasma gallisepticum Through Modulation of MAPK/ERK/JNK Signaling and Immunosuppression. J. Integr. Agric. 2025, 24, 2356–2370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosecka-Strojek, M.; Trzeciak, J.; Homa, J.; Trzeciak, K.; Władyka, B.; Trela, M.; Międzobrodzki, J.; Lis, M.W. Effect of Staphylococcus aureus infection on the heat stress protein 70 (HSP70) level in chicken embryo tissues. Poult. Sci. 2021, 100, 101119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chico, V.; Salvador-Mira, M.E.; Nombela, I.; Puente-Marin, S.; Ciordia, S.; Mena, M.C.; Perez, L.; Coll, J.; Guzman, F.; Encinar, J.A.; et al. IFIT5 Participates in the Antiviral Mechanisms of Rainbow Trout Red Blood Cells. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giroud-Gerbetant, J.; Sotillo, F.; Hernández, G.; Ruano, I.; Sebastián, D.; Fort, J.; Sánchez, M.; Weiss, G.; Prats, N.; Zorzano, A.; et al. Defective Slc7a7 transport reduces erythropoietin compromising erythropoiesis. Mol. Med. 2025, 31, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quenum, A.J.I.; Shukla, A.; Rexhepi, F.; Cloutier, M.; Ghosh, A.; Kufer, T.A.; Ramanathan, S.; Ilangumaran, S. NLRC5 Deficiency Deregulates Hepatic Inflammatory Response but Does Not Aggravate Carbon Tetrachloride-Induced Liver Fibrosis. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 749646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeudall, S.; Upchurch, C.M.; Leitinger, N. The clinical relevance of heme detoxification by the macrophage heme oxygenase system. Front. Immunol. 2024, 1, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surai, P.F. Antioxidant Systems in Poultry Biology: Superoxide Dismutase. J. Anim. Res. Nutr. 2016, 1, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cai, F.; Wang, X.; Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, W. Integrated Single-Cell and Bulk Transcriptomics Unveils Immune Profiles in Chick Erythroid Cells upon Avian Pathogenic Escherichia coli Infection. Animals 2026, 16, 179. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020179

Cai F, Wang X, Wang C, Wang Y, Zhang W. Integrated Single-Cell and Bulk Transcriptomics Unveils Immune Profiles in Chick Erythroid Cells upon Avian Pathogenic Escherichia coli Infection. Animals. 2026; 16(2):179. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020179

Chicago/Turabian StyleCai, Fujuan, Xianjue Wang, Chunzhi Wang, Yuzhen Wang, and Wenguang Zhang. 2026. "Integrated Single-Cell and Bulk Transcriptomics Unveils Immune Profiles in Chick Erythroid Cells upon Avian Pathogenic Escherichia coli Infection" Animals 16, no. 2: 179. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020179

APA StyleCai, F., Wang, X., Wang, C., Wang, Y., & Zhang, W. (2026). Integrated Single-Cell and Bulk Transcriptomics Unveils Immune Profiles in Chick Erythroid Cells upon Avian Pathogenic Escherichia coli Infection. Animals, 16(2), 179. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020179