Aster pekinensis Extract Mitigates High-Fat-Diet-Induced Obesity and Metabolic Dysfunction in Mice

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Extraction and Preparation

2.2. UPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS/MS Analysis

2.3. Ethical Statement

2.4. Animal Study

2.5. Histopathological Analysis

2.6. Liver Index and NAFLD Activity Score Analysis

2.7. Serum Biochemical Analysis

2.8. Intraperitoneal Glucose Tolerance Testing (IPGTT) and Intraperitoneal Insulin Tolerance Testing (IPITT)

2.9. Reverse Transcription qPCR (RT-qPCR)

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

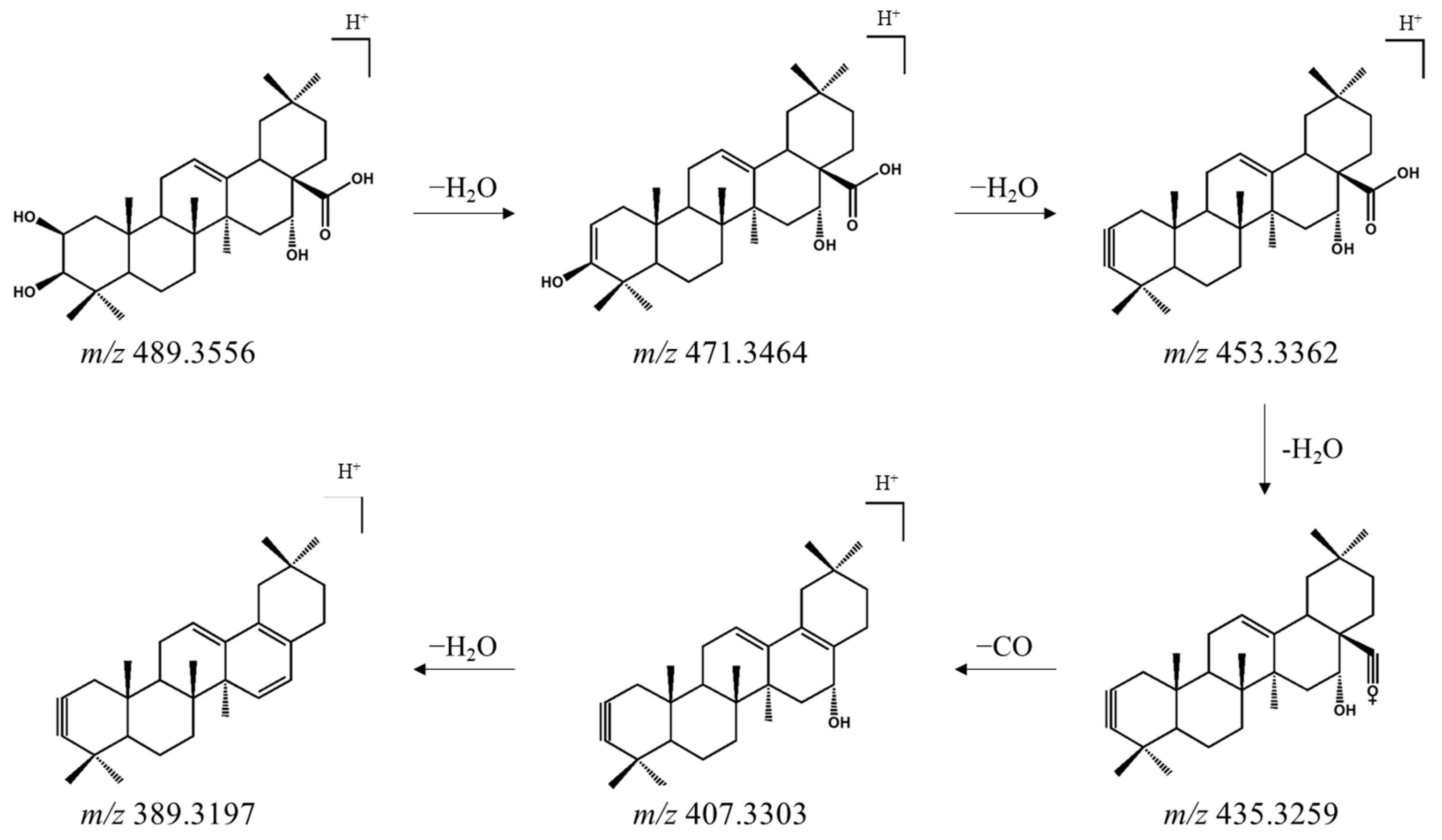

3.1. Identification of Oleanane-Type Saponins in AP Extract Using UPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS/MS

3.2. AP Extract Reduces Body-Weight Gain and Improves Food Efficiency in C57BL/6 Mice with HFD-Induced Obesity

3.3. AP Extract Reduces Fat Accumulation in C57BL/6 Mice with HFD-Induced Obesity

3.4. AP Extract Attenuates Adipocyte Hypertrophy in Epididymal WAT

3.5. AP Improves Blood Glucose and Blood Lipids in HFD-Induced Obese Mice

3.6. AP Attenuates HFD-Induced Hepatomegaly, NAFLD, and Liver Injury

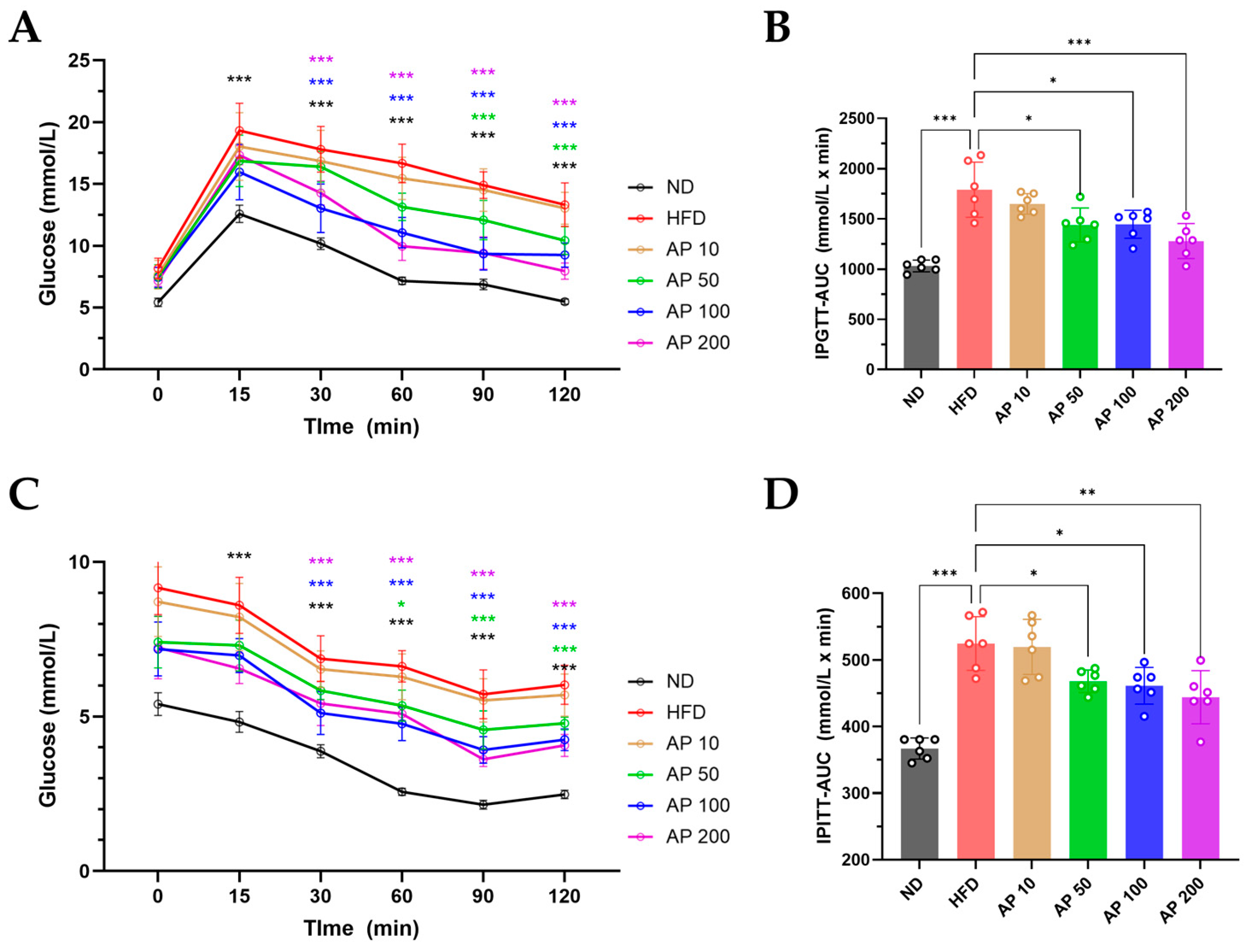

3.7. AP Improves IPGTT/IPITT and Modulates Hepatic De Novo Lipogenesis and Inflammation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chandler, M.; Cunningham, S.; Lund, E.M.; Khanna, C.; Naramore, R.; Patel, A.; Day, M.J. Obesity and Associated Comorbidities in People and Companion Animals: A One Health Perspective. J. Comp. Pathol. 2017, 156, 296–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- German, A.J. The growing problem of obesity in dogs and cats. J. Nutr. 2006, 136, 1940s–1946s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilor, C.; Graves, T.K. Diabetes Mellitus in Cats and Dogs. Vet. Clin. N. Am.-Small Anim. Pract. 2023, 53, Xiii–Xiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misha, M.S.; Destrumelle, S.; Le Jan, D.; Mansour, N.M.; Fizanne, L.; Ouguerram, K.; Desfontis, J.C.; Mallem, M.Y. Preventive effects of a nutraceutical mixture of berberine, citrus and apple extracts on metabolic disturbances in Zucker fatty rats. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0306783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Ballantyne, C.M. Metabolic Inflammation and Insulin Resistance in Obesity. Circ. Res. 2020, 126, 1549–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, T.L.; Molina, J.; Sheridan, L.; du Plessis, H.; Brown, J.; Abraham, H.; Morton, O.; Mckay, S. Developing and evaluating a health pack to support dog owners to manage the weight of their companion animals. Front. Vet. Sci. 2025, 11, 1483130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, J.A.; Villaverde, C. Scope of the Problem and Perception by Owners and Veterinarians. Vet. Clin. N. Am.-Small Anim. Pract. 2016, 46, 761–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhatib, A.; Tsang, C.; Tiss, A.; Bahorun, T.; Arefanian, H.; Barake, R.; Khadir, A.; Tuomilehto, J. Functional Foods and Lifestyle Approaches for Diabetes Prevention and Management. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Amersfort, K.; van der Lee, A.; Hagen-Plantinga, E. Evidence-base for the beneficial effect of nutraceuticals in canine dermatological immune-mediated inflammatory diseases—A literature review. Vet. Dermatol. 2023, 34, 266–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.D.; Jang, H.J.; Wang, C.Y.; Lee, S.W.; Rho, M.C.; Kim, Y.H.; Yang, S.Y. Anti-inflammatory Potential of Saponins from via NF-κB/MAPK Activation. J. Nat. Prod. 2019, 82, 1139–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, F.; Huang, R.; Lin, D.; Wang, Y.; Yang, X.; Huang, X.; Zheng, B.; Chen, Z.; Huang, Y.; Wang, X.; et al. Resveratrol Improves Liver Steatosis and Insulin Resistance in Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Association with the Gut Microbiota. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 611323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barazzoni, R.; Bischoff, S.C.; Busetto, L.; Cederholm, T.; Chourdakis, M.; Cuerda, C.; Delzenne, N.; Genton, L.; Schneider, S.; Singer, P.; et al. Nutritional management of individuals with obesity and COVID-19: ESPEN expert statements and practical guidance. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 41, 2869–2886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, L.; Su, Z.; Wang, S. The anti-obesity effects of polyphenols: A comprehensive review of molecular mechanisms and signal pathways in regulating adipocytes. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1393575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayed, U.F.S.M.; Moshawih, S.; Goh, H.P.; Kifli, N.; Gupta, G.; Singh, S.K.; Chellappan, D.K.; Dua, K.; Hermansyah, A.; Ser, H.L.; et al. Natural products as novel anti-obesity agents: Insights into mechanisms of action and potential for therapeutic management. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1182937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagao, T.; Okabe, H.; Yamauchi, T. Studies on the Constituents of Aster tataricus L. f. I.: Structures of Shionosides a and B: Monoterpene Glycosides Isolated from the Root. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1988, 36, 571–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagao, T.; Okabe, H.; Yamauchi, T. Studies on the Constituents of Aster tataricus L. f. III.: Structures of Aster Saponins E and F Isolated from the Root. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1990, 38, 783–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dongliang, C.; Yu, S. Terpenoid glycosides from the roots of Aster tataricus. Phytochemistry 1993, 35, 173–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoenig, M. Comparative Aspects of Human, Canine, and Feline Obesity and Factors Predicting Progression to Diabetes. Vet. Sci. 2014, 1, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Li, L. The Role of Plant Extracts in Enhancing Nutrition and Health for Dogs and Cats: Safety, Benefits, and Applications. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roudebush, P.; Schoenherr, W.D.; Delaney, S.J. Timely topics in nutrition—An evidence-based review of the use of nutraceuticals and dietary supplementation for the management of obese and overweight pets. Javma-J. Am. Vet. Med. A 2008, 232, 1646–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.S.; Jung, J.I.; Hwang, J.S.; Hwang, M.O.; Kim, E.J. Cydonia oblonga Miller fruit extract exerts an anti-obesity effect in 3T3-L1 adipocytes by activating the AMPK signaling pathway. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2023, 17, 1043–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Oh, K.S.; Yoon, Y.; Park, J.S.; Park, Y.S.; Han, J.H.; Jeong, A.L.; Lee, S.; Park, M.; Choi, Y.A.; et al. Herbal extract THI improves metabolic abnormality in mice fed a high-fat diet. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2011, 5, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, A.; Terauchi, Y. Lessons from Mouse Models of High-Fat Diet-Induced NAFLD. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 21240–21257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Recena Aydos, L.; Aparecida do Amaral, L.; Serafim de Souza, R.; Jacobowski, A.C.; Freitas Dos Santos, E.; Rodrigues Macedo, M.L. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Induced by High-Fat Diet in C57bl/6 Models. Nutrients 2019, 11, 3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, A.; Tammen, S.A.; Park, S.; Han, S.N.; Choi, S.W. Genome-wide hepatic DNA methylation changes in high-fat diet-induced obese mice. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2017, 11, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Y.; Liao, J.K. A mouse model of diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance. Methods Mol. Biol. 2012, 821, 421–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.G.; Ren, N.N.; Li, S.Y.; Chen, M.; Pu, P. Novel anti-obesity effect of scutellarein and potential underlying mechanism of actions. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 117, 109042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drummer, C.; Saaoud, F.; Jhala, N.C.; Cueto, R.; Sun, Y.; Xu, K.M.; Shao, Y.; Lu, Y.F.; Shen, H.M.; Yang, L.; et al. Caspase-11 promotes high-fat diet-induced NAFLD by increasing glycolysis, OXPHOS, and pyroptosis in macrophages. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1113883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, D.R.; Hosker, J.P.; Rudenski, A.S.; Naylor, B.A.; Treacher, D.F.; Turner, R.C. Homeostasis model assessment: Insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia 1985, 28, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, Y.B.; Kwon, H.J.; Sharif, M.; Lim, J.; Lee, I.C.; Ryu, Y.B.; Lee, J.I.; Kim, J.S.; Lee, Y.S.; Kim, D.H.; et al. Therapeutic strategy targeting host lipolysis limits infection by SARS-CoV-2 and influenza A virus. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, A.; Takeuchi, M.; Oikawa, K.; Sonoda, K.H.; Usui, Y.; Okunuki, Y.; Takeda, A.; Oshima, Y.; Yoshida, K.; Usui, M.; et al. Effects of dioxin on vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) production in the retina associated with choroidal neovascularization. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2009, 50, 3410–3416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleiner, D.E.; Brunt, E.M.; Van Natta, M.; Behling, C.; Contos, M.J.; Cummings, O.W.; Ferrell, L.D.; Liu, Y.C.; Torbenson, M.S.; Unalp-Arida, A.; et al. Design and validation of a histological scoring system for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2005, 41, 1313–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirabelli, M.; Misiti, R.; Sicilia, L.; Brunetti, F.S.; Chiefari, E.; Brunetti, A.; Foti, D.P. Hypoxia in Human Obesity: New Insights from Inflammation towards Insulin Resistance—A Narrative Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, G.-S.; Jo, H.-J.; Lee, Y.-R.; Oh, T.; Park, H.-J.; Ahn, G.O. Sensing the oxygen and temperature in the adipose tissues—Who’s sensing what? Exp. Mol. Med. 2023, 55, 2300–2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, Y.A. The SCAP/SREBP Pathway: A Mediator of Hepatic Steatosis. Endocrinol. Metab. 2017, 32, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferré, P.; Foufelle, F. Hepatic steatosis: A role for lipogenesis and the transcription factor SREBP-1c. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2010, 12, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millán, J.; Pintó, X.; Muñoz, A.; Zúñiga, M.; Rubiés-Prat, J.; Pallardo, L.F.; Masana, L.; Mangas, A.; Hernández-Mijares, A.; González-Santos, P.; et al. Lipoprotein ratios: Physiological significance and clinical usefulness in cardiovascular prevention. Vasc. Health Risk Man. 2009, 5, 757–765. [Google Scholar]

- Rains, T.M.; Agarwal, S.; Maki, K.C. Antiobesity effects of green tea catechins: A mechanistic review. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2011, 22, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloo, S.O.; Ofosu, F.K.; Kim, N.H.; Kilonzi, S.M.; Oh, D.H. Insights on Dietary Polyphenols as Agents against Metabolic Disorders: Obesity as a Target Disease. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- German, A.J. Weight management in obese pets: The tailoring concept and how it can improve results. Acta Vet. Scand. 2016, 58, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porsani, M.Y.H.; Teixeira, F.A.; Amaral, A.R.; Pedrinelli, V.; Vasques, V.; de Oliveira, A.G.; Vendramini, T.H.A.; Brunetto, M.A. Factors associated with failure of dog’s weight loss programmes. Vet. Med. Sci. 2020, 6, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broome, H.A.O.; Woods-Lee, G.R.T.; Flanagan, J.; Biourge, V.; German, A.J. Weight loss outcomes are generally worse for dogs and cats with class II obesity, defined as >40% overweight. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 22958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, J.H.; Sung, J.H.; Huh, J.Y. Diverse Functions of Macrophages in Obesity and Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease: Bridging Inflammation and Metabolism. Immune Netw. 2025, 25, e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quang, T.H.; Nguyen, T.T.N.; Minh, C.V.; Kiem, P.V.; Thao, N.P.; Tai, B.H.; Nhiem, N.X.; Song, S.B.; Kim, Y.H. Effect of triterpenes and triterpene saponins from the stem bark of on the transactivational activities of three PPAR subtypes. Carbohyd. Res. 2011, 346, 2567–2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Yan, X.T.; Sun, Y.N.; Ngan, T.T.; Shim, S.H.; Kim, Y.H. Anti-Inflammatory and PPAR Transactivational Effects of Oleanane-Type Triterpenoid Saponins from the Roots of Pulsatilla koreana. Biomol. Ther. 2014, 22, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, P.Y.; Liu, Y.J. Terpenoids: Natural Compounds for Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) Therapy. Molecules 2023, 28, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.; Feng, R.B.; Wu, Q.S.; Wan, J.B.; Zhang, Q.W. Total saponins from Panax japonicus attenuate acute alcoholic liver oxidative stress and hepatosteatosis by p62-related Nrf2 pathway and AMPK-ACC/PPARα axis in vivo and in vitro. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2023, 317, 116785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, F.; Ren, X.; Du, B.; Yang, Y. Pyrus ussuriensis Maxim 70% ethanol eluted fraction ameliorates inflammation and oxidative stress in LPS-induced inflammation in vitro and in vivo. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 11, 458–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, Y.M.; Wu, Y.T.; Chen, L.; Tan, Z.B.; Fan, H.J.; Xie, L.P.; Zhang, W.T.; Chen, H.M.; Li, J.; Liu, B.; et al. 3,5-Dicaffeoylquinic acid protects H9C2 cells against oxidative stress-induced apoptosis via activation of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Food Nutr. Res. 2018, 62, 1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.H.; Karadeniz, F.; Lee, J.I.; Seo, Y.; Kong, C.S. Protective effect of 3,5-dicaffeoyl-epi-quinic acid against UVB-induced photoaging in human HaCaT keratinocytes. Mol. Med. Rep. 2019, 20, 763–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Jian, T.; Li, J.; Lv, H.; Tong, B.; Li, J.; Meng, X.; Ren, B.; Chen, J. Chicoric Acid Ameliorates Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease via the AMPK/Nrf2/NFkappaB Signaling Pathway and Restores Gut Microbiota in High-Fat-Diet-Fed Mice. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2020, 9734560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Duan, J.; Jia, N.; Liu, M.; Cao, S.; Weng, Y.; Zhang, W.; Cao, J.; Li, R.; Cui, J.; et al. IRS-2/Akt/GSK-3beta/Nrf2 Pathway Contributes to the Protective Effects of Chikusetsu Saponin IVa against Lipotoxicity. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 8832318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Bai, L.; Yang, X.; Huang, J.; Wang, J.; Wu, X.; Shi, J. Recent advances in anti-inflammation via AMPK activation. Heliyon 2024, 10, e33670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubota, N.; Kubota, T.; Kajiwara, E.; Iwamura, T.; Kumagai, H.; Watanabe, T.; Inoue, M.; Takamoto, I.; Sasako, T.; Kumagai, K.; et al. Differential hepatic distribution of insulin receptor substrates causes selective insulin resistance in diabetes and obesity. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavaliere, G.; Cimmino, F.; Trinchese, G.; Catapano, A.; Petrella, L.; D’Angelo, M.; Lucchin, L.; Mollica, M.P. From Obesity-Induced Low-Grade Inflammation to Lipotoxicity and Mitochondrial Dysfunction: Altered Multi-Crosstalk between Adipose Tissue and Metabolically Active Organs. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Hierro, J.N.; Herrera, T.; Fornari, T.; Reglero, G.; Martin, D. The gastrointestinal behavior of saponins and its significance for their bioavailability and bioactivities. J. Funct. Foods 2018, 40, 484–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.C.; Xu, W.C.; Zhang, Y.; Di, L.Q.; Shan, J.J. A review of saponin intervention in metabolic syndrome suggests further study on intestinal microbiota. Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 160, 105088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Z.H.; Yuan, C.J.; Zhang, F.; Huan, M.L.; Cao, W.D.; Li, K.C.; Yang, J.Y.; Cao, D.Y.; Zhou, S.Y.; Mei, Q.B. Intestinal Absorption and First-Pass Metabolism of Polyphenol Compounds in Rat and Their Transport Dynamics in Caco-2 Cells. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e29647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.W.; Wang, N.; Li, W.; Xu, W.; Wu, S. Biotransformation of 4,5--dicaffeoylquinic acid methyl ester by human intestinal flora and evaluation on their inhibition of NO production and antioxidant activity of the products. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013, 55, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.-W.; Seol, I.-C.; Son, C.-G. Interpretation of Animal Dose and Human Equivalent Dose for Drug Development. J. Korean Orient. Med. 2010, 31, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Nair, A.B.; Jacob, S. A simple practice guide for dose conversion between animals and human. J. Basic Clin. Pharm. 2016, 7, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikawa, S.; Yasoshima, A.; Doi, K.; Nakayama, H.; Uetsuka, K. Involvement of sex, strain and age factors in high fat diet-induced obesity in C57BL/6J and BALB/cA mice. Exp. Anim. 2007, 56, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Herck, M.A.; Vonghia, L.; Francque, S.M. Animal Models of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease—A Starter’s Guide. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes Schmitt, E.; Erminda Schreiner, G.; Smolski dos Santos, L.; Pereira de Oliveira, C.; Berny Pereira, C.; Muller de Moura Sarmento, S.; Klock, C.; Casanova Petry, C.; Denardin, E.L.G.; Gonçalves, I.L.; et al. Moro Orange (Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck) Extract Mitigates Metabolic Dysregulation, Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, and Adipose Tissue Hyperplasia in Obese Rats. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolliffe, I.T.; Cadima, J. Principal component analysis: A review and recent developments. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 2016, 374, 20150202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.H.; Kim, Y.-S.; Song, M.; Lee, M.; Park, J.; Kim, H. A Herbal Formula HT048, Citrus unshiu and Crataegus pinnatifida, Prevents Obesity by Inhibiting Adipogenesis and Lipogenesis in 3T3-L1 Preadipocytes and HFD-Induced Obese Rats. Molecules 2015, 20, 9656–9670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | ND | HFD |

|---|---|---|

| Protein (% of total energy) | 20 | 20 |

| Fat (% of total energy) | 10 | 60 |

| Carbohydrate (% of total energy) | 70 | 20 |

| Energy density (kcal/g) | 3.85 | 5.24 |

| Name | Forward (5′ → 3′) | Reverse (5′ → 3′) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACC1 | TTCAGTTCATGCTGCCCACA | AGGTTGGAGGCAAAGGACAT | [30] |

| SREBP-1c | AAGACAGATGCAGGAGCCAC | CCTCCACTCACCAGGGTCT | [30] |

| TNF-α | CCCACGTCGTAGCAAACCA | CTTTGAGATCCATGCCGTTGG | [30] |

| MCP-1 | TCACCAGCAAGATGATCCCA | GAGCTTGGTGACAAAAACTACA | [30] |

| β-actin | AGCCTTCCTTCTTGGGTATGG | CACTTGCGGTGCACGATGGAG | [31] |

| No. | tR (min) | Mode of Ionization | Measured Mass (Da) | Calculated Mass (Da) | Mass Error (ppm) | Molecular Formula | Fragment Ions (m/z) | Predicted Compounds |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4.88 | [M + Na]+ | 551.1940 | 551.1952 | −0.3 | C21H36O15 | 483.1490, 323.1076 | Unknown |

| 2 | 7.51 | [M + Na]+ | 771.2526 | 771.2535 | −0.3 | C29H48O22 | 443.3215 | Unknown |

| 3 | 7.52 | [M + Na]+ | 425.1437 | 425.1424 | −0.2 | C18H26O10 | 343.1753 | Unknown |

| 4 | 7.54 | [M + Na]+ | 409.1836 | 409.1838 | 1.4 | C19H30O8 | 207.1388 | Vomifoliol glucoside |

| 5 | 8.01 | [M + Na]+ | 409.1831 | 409.1838 | 0.0 | C19H30O8 | 207.1387 | Vomifoliol glucoside |

| 6 | 12.28 | [M + H]+ | 517.1342 | 517.1346 | 0.8 | C25H24O12 | 499.1231, 163.0396 | 3,4-Dicaffeoylquinic acid |

| 7 | 12.67 | [M + Na]+ | 539.1157 | 539.1165 | 0.4 | C25H24O12 | 499.1237, 163.0396 | 3,5-Dicaffeoylquinic acid |

| 8 | 13.01 | [M + Na]+ | 605.1471 | 605.1482 | −0.9 | C26H30O15 | 343.1026 | Unknown |

| 9 | 13.05 | [M + Na]+ | 527.2460 | 527.2468 | −0.2 | C24H40O11 | 319.2268 | Unknown |

| 10 | 13.26 | [M + H]+ | 479.1187 | 479.1190 | −1.3 | C22H22O12 | 317.0656 | Isorhamnetin-3-glucoside |

| 11 | 13.60 | [M + H]+ | 517.1348 | 517.1346 | −0.4 | C25H24O12 | 499.1243, 163.0395 | 4,5-Dicaffeoylquinic acid |

| 12 | 14.10 | [M + Na]+ | 681.2338 | 681.2336 | 3.7 | C30H42O16 | 601.2844, 533.1143, 517.1438, 461.1841, 397.1255 | Unknown |

| 13 | 14.50 | [M + Na]+ | 601.2838 | 601.2836 | 0.3 | C27H46O13 | 421.2197, 309.1273 | Unknown |

| 14 | 14.92 | [M + H]+ | 1269.6136 | 1269.6116 | 1.6 | C59H96O29 | 1107.5569, 945.5045, 813.4557, 667.4038, 487.3434 | 2,3,6,16-Tetrahydroxyolean-12-en-28-oic acid + 3Glc + Rha + Xyl |

| 15 | 15.24 | [M + Na]+ | 1261.5823 | 1261.5829 | −0.5 | C58H94O28 | 1099.5304, 487.3423 | 2,3,6,16-Tetrahydroxyolean-12-en-28-oic acid + 3Glc+ Rha + Xyl |

| 16 | 16.00 | [M + Na]+ | 1437.6548 | 1437.6514 | 2.4 | C65H106O33 | 813.4620, 651.4080, 453.3378 | 2,3,16-Trihydroxyolean-12-en-28-oic acid + 4Glc + Rha+ Xyl |

| 17 | 16.34 | [M + H]+ | 1385.6667 | 1385.6589 | 5.6 | C64H104O32 | 783.4531, 453.3374 | 2,3,16-Trihydroxyolean-12-en-28-oic acid + 3Glc + Rha + 2Xyl |

| 18 | 16.39 | [M + H]+ | 1385.6633 | 1385.6589 | 3.2 | C64H104O32 | 783.4539, 453.3339 | 2,3,16-Trihydroxyolean-12-en-28-oic acid + 3Glc + Rha + 2Xyl |

| 19 | 16.48 | [M + H]+ | 1253.6161 | 1253.6166 | −0.4 | C59H96O28 | 1091.5657, 651.4111, 453.3368 | 2,3,16-Trihydroxyolean-12-en-28-oic acid + 3Glc + Rha + Xyl |

| 20 | 16.80 | [M + H]+ | 1355.6559 | 1355.6483 | 5.6 | C63H102O31 | 1223.6074, 929.5042, 783.4551, 651.4108, 453.3361 | 2,3,16-Trihydroxyolean-12-en-28-oic acid + 2Glc + Rha + 3Xyl |

| 21 | 16.90 | [M + H]+ | 1223.6062 | 1223.6061 | 0.1 | C58H94O27 | 1061.5507, 929.5118, 797.4664, 783.4521, 651.4119, 453.3367 | 2,3,16-Trihydroxyolean-12-en-28-oic acid + 2Glc + Rha + 2Xyl |

| 22 | 16.98 | [M + H]+ | 1253.6179 | 1256.6177 | 1.0 | C59H96O28 | 1091.5616, 929.5111, 797.4672, 651.4097, 453.3361 | 2,3,16-Trihydroxyolean-12-en-28-oic acid + 3Glc + Rha + Xyl |

| 23 | 17.09 | [M + H]+ | 1355.6532 | 1355.6483 | 3.6 | C63H102O31 | 1223.6051, 1077.5493, 929.5161, 783.4519, 651.4115, 453.3372 | 2,3,16-Trihydroxyolean-12-en-28-oic acid + 2Glc + Rha + 3Xyl |

| 24 | 17.35 | [M + H]+ | 1267.5990 | 1267.5959 | 2.4 | C59H94O29 | 1105.5425, 943.4988, 453.3363 | Triterpenoid peantaglycoside |

| 25 | 17.52 | [M + H]+ | 1223.6061 | 1223.6061 | 0.0 | C58H94O27 | 1091.5635, 929.5109, 797.4680, 651.4106, 453.3366 | 2,3,16-Trihydroxyolean-12-en-28-oic acid + 2Glc + Rha + 2Xyl |

| 26 | 17.58 | [M + H]+ | 1091.5642 | 1091.5638 | 0.4 | C53H86O23 | 929.5074, 797.4469, 651.4102, 453.3365 | 2,3,16-Trihydroxyolean-12-en-28-oic acid + 2Glc + Rha + Xyl |

| 27 | 17.84 | [M + H]+ | 1237.5847 | 1237.5853 | −0.5 | C58H92O28 | 1075.5381, 959.4803, 503.3332, 485.3268 | 2,3-Dihydroxyolean-12-en-23,28-dioic acid + 2Glc + Rha + 2Xyl |

| 28 | 17.99 | [M + Na]+ | 965.4346 | 965.4335 | 1.1 | C46H70O20 | 517.3152, 499.3055 | 2,3,16,21-Tetrahydroxyolean-12-en-23,28-dioic acid 28,21-lactone+ Glc + 2Xyl |

| 29 | 18.12 | [M + Na]+ | 1405.6241 | 1405.6252 | −0.8 | C64H102O32 | 487.3412, 469.3289 | 2,3,16-Trihydroxyolean-11,13-dien-28-oic acid + 3Glc + Rha + 2Xyl |

| 30 | 18.46 | [M + Na]+ | 1113.5409 | 1113.5458 | −4.4 | C53H86O23 | 929.5071, 767.4554, 635.4135, 453.3359 | 2,3,16-Trihydroxyolean-12-en-28-oic acid + 2Glc + Rha + Xyl |

| 31 | 18.62 | [M + H]+ | 1061.5521 | 1061.5532 | −1.0 | C52H84O22 | 929.5017, 783.4482, 767.4537, 651.4095, 635.4178, 453.3362 | 2,3,16-Trihydroxyolean-12-en-28-oic acid + Glc + Rha + 2Xyl |

| 32 | 18.82 | [M + Na]+ | 1229.5554 | 1229.5567 | −1.1 | C57H90O27 | 929.4728, 517.3134, 499.3031 | Triterpenoid peantaglycoside |

| 33 | 19.01 | [M + Na]+ | 1083.5349 | 1083.5352 | −0.3 | C52H84O22 | 929.5099, 783.4523, 635.4162, 453.3362 | 2,3,16-Trihydroxyolean-12-en-28-oic acid + Glc + Rha + 2Xyl |

| 34 | 19.07 | [M + Na]+ | 1215.5753 | 1215.5775 | −1.8 | C57H92O26 | 1061.5514, 929.5085, 767.4568, 635.4125, 453.3356 | 2,3,16-Trihydroxyolean-12-en-28-oic acid + Glc + Rha + 3Xyl |

| 35 | 19.27 | [M + H]+ | 1091.5629 | 1091.5638 | −0.8 | C53H86O23 | 959.5194, 797.4645, 635.4150, 453.3361 | 2,3,16-Trihydroxyolean-12-en-28-oic acid + 2Glc + Rha + Xyl |

| 36 | 19.48 | [M + Na]+ | 1083.5325 | 1083.5352 | −2.5 | C52H84O22 | 929.5079, 767.4580, 635.4149, 453.3556 | 2,3,16-Trihydroxyolean-12-en-28-oic acid + Glc + Rha + 2Xyl |

| 37 | 19.65 | [M + H]+ | 1091.5605 | 1091.5638 | −3.0 | C53H86O23 | 797.4366, 503.3375, 485.3260 | Triterpenoid tetraglycoside |

| 38 | 19.79 | [M + Na]+ | 833.3936 | 833.3936 | 0.0 | C41H62O16 | 679.3704, 517.3165, 499.3063 | 2,3,16,21-Tetrahydroxyolean-12-en-23,28-dioic acid 28,21-lactone + Glc + Xyl |

| 39 | 19.96 | [M + H]+ | 1061.5521 | 1061.5532 | −1.0 | C52H84O22 | 929.5098, 797.4664, 767.4575, 635.4152, 453.3362 | 2,3,16-Trihydroxyolean-12-en-28-oic acid + Glc + Rha + 2Xyl |

| 40 | 20.07 | [M + H]+ | 929.5092 | 929.5110 | −1.9 | C47H76O18 | 797.4678, 635.4157, 453.3360 | 2,3,16-Trihydroxyolean-12-en-28-oic acid + Glc + Rha + Xyl |

| 41 | 21.08 | [M + Na]+ | 981.5063 | 981.5035 | 2.9 | C48H78O19 | 819.4191, 635.4167, 453.3372 | 2,3,16-Trihydroxyolean-12-en-28-oic acid + 2Glc + Rha |

| 42 | 21.53 | [M + H]+ | 1369.6694 | 1369.6640 | 3.9 | C64H104O31 | 1237.6249, 1091.5521, 929.5083, 487.3424 | 2,3,6,16-Tetrahydroxyolean-12-en-28-oic acid + 3Glc + Rha + Xyl |

| 43 | 21.81 | [M + Na]+ | 1377.6309 | 1377.6303 | 0.4 | C63H102O31 | 1223.6036, 487.3375 | 2,3,6,16-Tetrahydroxyolean-12-en-28-oic acid + 3Glc + Rha + Xyl |

| 44 | 21.89 | [M + Na]+ | 967.4510 | 967.4515 | −0.5 | C46H72O20 | 813.4247, 453.3371 | Triterpenoid triglycoside |

| 45 | 22.04 | [M + H]+ | 1237.6230 | 1237.6217 | 1.1 | C59H96O27 | 1105.5790, 1091.5626, 959.5242, 487.3428 | 2,3,6,16-Tetrahydroxyolean-12-en-28-oic acid + 3Glc + Rha + Xyl |

| 46 | 22.14 | [M + Na]+ | 951.4934 | 951.4930 | 0.4 | C47H76O18 | 635.4149, 453.3368 | 2,3,16-Trihydroxyolean-12-en-28-oic acid + Glc + Rha + Xyl |

| 47 | 22.88 | [M + Na]+ | 1345.6025 | 1345.6041 | −1.2 | C62H98O30 | 1191.5811, 473.3271 | Triterpenoid peantaglycoside |

| 48 | 22.95 | [M + H]+ | 1191.5847 | 1191.5799 | 4.0 | C57H90O26 | 1045.5159, 473.3267 | Triterpenoid tetraglycoside |

| 49 | 23.60 | [M + Na]+ | 1111.5315 | 1111.5301 | 1.3 | C53H84O23 | 957.5078, 473.3265 | Triterpenoid tetraglycoside |

| 50 | 23.78 | [M + Na]+ | 1477.6464 | 1477.6463 | 0.1 | C67H106O34 | 681.2885, 473.3246 | Triterpenoid hexaglycoside |

| 51 | 24.08 | [M + H]+ | 1455.6688 | 1455.6644 | 3.0 | C67H106O34 | 1323.6157, 473.3232 | Triterpenoid hexaglycoside |

| 52 | 24.13 | [M + H]+ | 1365.6348 | 1365.6327 | 1.5 | C64H100O31 | 1191.5837, 1045.5164, 487.3355 | Triterpenoid hexaglycoside |

| 53 | 24.22 | [M + H]+ | 1177.5974 | 1177.6006 | −2.7 | C57H92O25 | 1045.5479, 487.3419 | Triterpenoid peantaglycoside |

| 54 | 24.35 | [M + Na]+ | 1081.5162 | 1081.5162 | −3.1 | C52H82O22 | 751.3569, 487.3407 | 2,3,16-Trihydroxyolean-11,13-dien-28-oic acid + Glc + Rha + 2Xyl |

| 55 | 25.28 | [M + H]+ | 1365.6355 | 1365.6327 | 2.1 | C64H100O31 | 1191.5891, 473.3268 | Triterpenoid peantaglycoside |

| 56 | 25.47 | [M + H]+ | 1455.7042 | 1455.7008 | 2.3 | C68H110O33 | 1191.6173, 487.3420 | Triterpenoid hexaglycoside |

| 57 | 25.86 | [M + H]+ | 1265.6177 | 1265.6166 | 0.9 | C60H96O28 | 1133.5748, 987.5201, 487.3414 | 2,3,6,16-Tetrahydroxyolean-12-en-28-oic acid + 3Glc + Rha + Xyl |

| 58 | 25.98 | [M + H]+ | 1323.6268 | 1323.6221 | 3.6 | C62H98O30 | 1191.5845, 1059.5306, 487.3489 | 2,3,16-Trihydroxyolean-11,13-dien-28-oic acid + Glc + Rha + 4Xyl |

| 59 | 26.26 | [M + H]+ | 1411.6802 | 1411.6745 | 4.0 | C66H106O32 | 1279.6354, 487.3660 | 2,3,6,16-Tetrahydroxyolean-12-en-28-oic acid + 3Glc + Rha + Xyl |

| 60 | 26.37 | [M + Na]+ | 1345.6036 | 1345.6041 | −0.4 | C62H98O30 | 1191.5786, 1059.5397, 487.3437 | 2,3,16-Trihydroxyolean-11,13-dien-28-oic acid + Glc + Rha + 4Xyl |

| 61 | 26.55 | [M + Na]+ | 1419.6461 | 1419.6408 | 3.7 | C65H104O32 | 1265.6193. 487.3432 | 2,3,6,16-Tetrahydroxyolean-12-en-28-oic acid + 3Glc + Rha + Xyl |

| 62 | 26.80 | [M + Na]+ | 1301.5820 | 1301.5778 | 3.2 | C60H94O29 | 1147.5524, 985.5131, 487.3415 | Triterpenoid peantaglycoside |

| 63 | 28.88 | [M + Na]+ | 1431.6439 | 1431.6408 | 2.2 | C66H104O32 | 1277.6174, 1131.5646, 983.5145, 453.3371 | Triterpenoid hexaglycoside |

| 64 | 29.90 | [M + H]+ | 1453.6885 | 1453.6851 | 2.3 | C68H108O33 | 1321.6450, 487.3407 | Triterpenoid hexaglycoside |

| 65 | 30.19 | [M + H]+ | 1439.6742 | 1439.6695 | 3.3 | C67H106O33 | 1307.6295, 487.3424 | 2,3,6,16-Tetrahydroxyolean-12-en-28-oic acid + 3Glc+ Rha + Xyl |

| 66 | 30.41 | [M + H]+ | 1453.6913 | 1453.6821 | 4.3 | C68H108O33 | 1321.6445, 487.3423 | Triterpenoid hexaglycoside |

| 67 | 30.71 | [M + H]+ | 1439.6765 | 1439.6695 | 4.9 | C67H106O33 | 1307.6289, 487.3435 | 2,3,6,16-Tetrahydroxyolean-12-en-28-oic acid + 3Glc + Rha + Xyl |

| 68 | 32.45 | [M + H]+ | 1305.6506 | 1305.6479 | 2.1 | C63H100O28 | 1173.6053, 1027.5429, 487.3442 | Triterpenoid peantaglycoside |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Moon, H.J.; Lee, S.-J.; Kim, G.W.; Baek, Y.-B.; Park, S.-I. Aster pekinensis Extract Mitigates High-Fat-Diet-Induced Obesity and Metabolic Dysfunction in Mice. Animals 2026, 16, 163. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020163

Moon HJ, Lee S-J, Kim GW, Baek Y-B, Park S-I. Aster pekinensis Extract Mitigates High-Fat-Diet-Induced Obesity and Metabolic Dysfunction in Mice. Animals. 2026; 16(2):163. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020163

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoon, Hyeon Jeong, Seon-Jin Lee, Geon Woo Kim, Yeong-Bin Baek, and Sang-Ik Park. 2026. "Aster pekinensis Extract Mitigates High-Fat-Diet-Induced Obesity and Metabolic Dysfunction in Mice" Animals 16, no. 2: 163. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020163

APA StyleMoon, H. J., Lee, S.-J., Kim, G. W., Baek, Y.-B., & Park, S.-I. (2026). Aster pekinensis Extract Mitigates High-Fat-Diet-Induced Obesity and Metabolic Dysfunction in Mice. Animals, 16(2), 163. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020163