Investigation of Mechanism of Small Peptide Application in Enhancing Laying Performance of Late-Laying Hens Through Bidirectional Liver–Gut Interactions

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals Preparation and Experimental Design

2.2. Productive Performances and Egg Quality Measurement

2.3. Serum Antioxidant Capacity, Immune Globulin, and Lipid Metabolism-Related Parameters

2.4. Intestinal Morphological and Microbial Determination

2.5. Liver Acquisition and Hepatic Gene Expression Measurement

2.6. Functional and Gene Set Enrichment Analysis of DEGs

2.7. Statistical Analysis and Mapping

3. Results

3.1. Effects of Supplement of Small Peptide on the Productive and Egg Quality

3.2. Effects of Supplementation of Small Peptides on Immunity, Antioxidant Capacities and Lipo-Metabolic Parameters

3.3. Effects of Supplement of Small Peptide on Intestine Morphological Parameters

3.4. Effects of Supplement of Small Peptide on Alpha Diversity

3.5. Effects of Supplement of Small Peptide on Beta Diversity

3.6. Effects of Supplementation of Small Peptides on Gut Microbial Communities

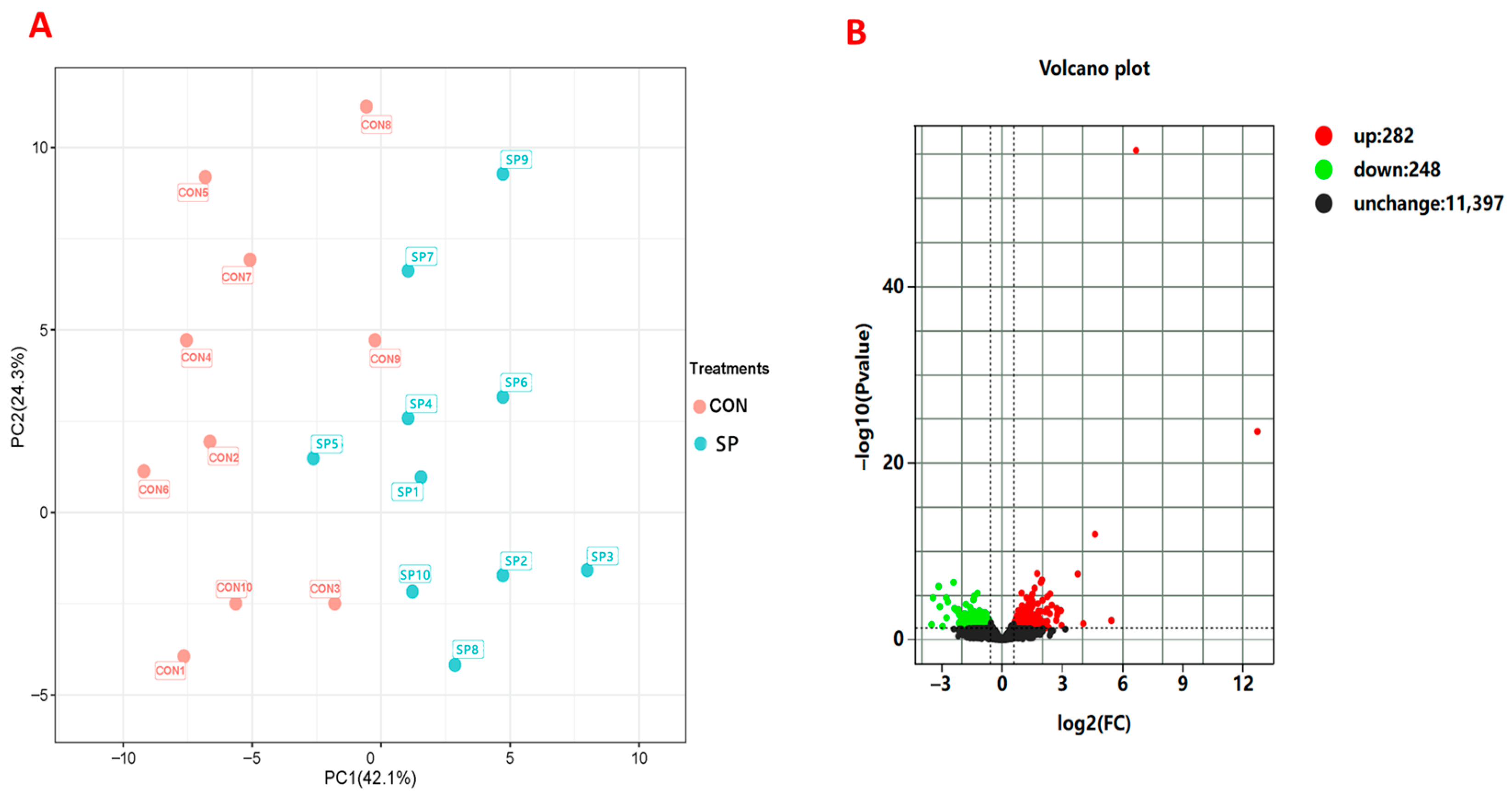

3.7. Effects of Supplementation of Small Peptides on Hepatic Gene Expressions

3.8. Interactive Crosstalk Between Hepatic Genes and Cecal Bacteria on Productive Performance and Egg Quality

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yao, H.; Hu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Rao, K.; Shi, S. Effects of dietary dimethylglycine supplementation on laying performance, egg quality, and tissue index of hens during late laying period. Poult. Sci. 2022, 101, 101610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiaodi, E.; Shao, D.; Li, M.; Shi, S.; Xiao, Y. Supplemental dietary genistein improves the laying performance and antioxidant capacity of Hy-Line brown hens during the late laying period. Poult. Sci. 2023, 102, 102573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Zhang, Y.; He, W.; Wei, Y.; Han, S.; Xia, L.; Tan, B.; Yu, J.; Kang, H.; Ma, M. Effects of small peptide supplementation on growth performance, intestinal barrier of laying hens during the brooding and growing periods. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 925256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, J.; Qiu, T.; Yan, X.; Wang, L.; Chen, Z.; Xiao, G.; Feng, X.; Zhang, H. Effect of replacing inorganic minerals with small peptide chelated minerals on production performance, some biochemical parameters and antioxidant status in broiler chickens. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 1027834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogut, M.H.; Genovese, K.J.; He, H.; Swaggerty, C.L.; Jiang, Y.W. BT cationic peptides: Small peptides that modulate innate immune responses of chicken heterophils and monocytes. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2012, 145, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osadchiy, V.; Martin, C.R.; Mayer, E.A. The gut–brain axis and the microbiome: Mechanisms and clinical implications. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 17, 322–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutsch, A.; Kantsjö, J.B.; Ronchi, F. The gut-brain axis: How microbiota and host inflammasome influence brain physiology and pathology. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 604179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, E.A.; Nance, K.; Chen, S. The gut–brain axis. Annu. Rev. Med. 2022, 73, 439–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gungor, B.; Adiguzel, E.; Gursel, I.; Yilmaz, B.; Gursel, M. Intestinal microbiota in patients with spinal cord injury. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0145878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolyen, E.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.R.; Bokulich, N.A.; Abnet, C.C.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Alexander, H.; Alm, E.J.; Arumugam, M.; Asnicar, F. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wen, D.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.; Pan, F.; Zhang, W.; Zhou, S.; Wang, F.; Mu, R. Pituitary transcriptome profile from laying period to incubation period of Changshun green-shell laying hens. BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bu, D.; Luo, H.; Huo, P.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, S.; He, Z.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, L.; Liu, J.; Guo, J. KOBAS-i: Intelligent prioritization and exploratory visualization of biological functions for gene enrichment analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, W317–W325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bezerra, L.R.; Sarmento, J.L.R.; Neto, S.G.; De Paula, N.R.O.; Oliveira, R.L.; Do Rêgo, W.M.F. Residual feed intake: A nutritional tool for genetic improvement. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2013, 45, 1649–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleimani, T.; Gilbert, H. Evaluating environmental impacts of selection for residual feed intake in pigs. Animal 2020, 14, 2598–2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, P.; Ducrocq, V.; Faverdin, P.; Friggens, N.C. Invited review: Disentangling residual feed intake—Insights and approaches to make it more fit for purpose in the modern context. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 6329–6342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, N.; Li, N.; Duan, X.; Niu, H. Interaction between the gut microbiome and mucosal immune system. Mil. Med. Res. 2017, 4, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoroso, C.; Perillo, F.; Strati, F.; Fantini, M.C.; Facciotti, F. The Role of Gut Microbiota Biomodulators on Mucosal Immunity and Intestinal Inflammation. Cells 2020, 9, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishnu, A.; Sung, W.; Kim, Y.; Min, K. Characterization of Microbiota Associated with Digesta and Mucosa in Different Regions of Gastrointestinal Tract of Nursery Pigs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Jeong, Y.; Kang, S.; You, H.J.; Ji, G.E. Co-culture with Bifidobacterium catenulatum improves the growth, gut colonization, and butyrate production of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii: In vitro and in vivo studies. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furter, M.; Sellin, M.E.; Hansson, G.C.; Hardt, W.D. Mucus architecture and near-surface swimming affect distinct Salmonella typhimurium infection patterns along the murine intestinal tract. Cell Rep. 2019, 27, 2665–2678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Meza Guzman, L.G.; Whitehead, L.; Leong, E.; Kueh, A.; Alexander, W.S.; Kershaw, N.J.; Babon, J.J.; Doggett, K.; Nicholson, S.E. SOCS2 regulation of growth hormone signaling requires a canonical interaction with phosphotyrosine. Biosci. Rep. 2022, 42, BSR20221683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letellier, E.; Haan, S. SOCS2: Physiological and pathological functions. Front. Biosci.-Landmark 2016, 8, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Xie, X.; Zou, G.; Kong, M.; Yang, J.; Chen, J.; Xiang, B. SOCS2 inhibits hepatoblastoma metastasis via downregulation of the JAK2/STAT5 signal pathway. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 21814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Han, S.; Jin, K.; Yu, T.; Zhang, G. SOCS2 Suppresses inflammation and apoptosis during nash progression through limiting NF-κB activation in macrophages. SSRN Electron. J. 2021, 17, 4165–4175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Fu, Y.; Zhou, S.; Zhao, P.; Zhao, J.; Yang, Q.; Wu, H.; Ding, M.; Li, Y. Comparison of the effect of quercetin and daidzein on production performance, anti-oxidation, hormones, and cecal microflora in laying hens during the late laying period. Poult. Sci. 2023, 102, 102674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Liu, L.; Fan, Z.; Niu, L.; Ning, W.; Cheng, H.; Li, M.; Huo, W.; Zhou, P.; Deng, H. Effect of different dietary oil sources on the performance, egg quality and antioxidant capacity during the late laying period. Poult. Sci. 2025, 104, 104615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Yang, H.; Zhang, L.; Su, Y.; Shi, D.; Xiao, H.; Tian, Y. High-throughput sequencing technology to reveal the composition and function of cecal microbiota in Dagu chicken. BMC Microbiol. 2016, 16, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.Y.; Dai, D.; Zhang, H.J.; Wu, S.G.; Qi, G.H.; Wang, J. The characterization of uterine calcium transport and metabolism during eggshell calcification of hens laying high or low breaking strength eggshell. Poult. Sci. 2025, 104, 105111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saki, A.A.; Alipana, A. Effect of dietary Wheat screening diet on broiler performance, intestinal viscosity and ileal protein digestibility. Int. J. Poult. Sci. 2005, 4, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apajalahti, J.; Vienola, K. Interaction between chicken intestinal microbiota and protein digestion. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2016, 221, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Gallausiaux, C.; Marinelli, L.; Blottière, H.M.; Larraufie, P.; Lapaque, N. SCFA: Mechanisms and functional importance in the gut. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2021, 80, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croucher, K.M.; Fleming, S.M. ATP13A2 (PARK9) and basal ganglia function. Front. Neurol. 2024, 14, 1252400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellanos-Jankiewicz, A.; Guzmán-Quevedo, O.; Fénelon, V.S.; Zizzari, P.; Quarta, C.; Bellocchio, L.; Tailleux, A.; Charton, J.; Fernandois, D.; Henricsson, M. Hypothalamic bile acid-TGR5 signaling protects from obesity. Cell Metab. 2021, 33, 1483–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ingredient | CON | SP |

|---|---|---|

| Corn | 61.1 | 61.1 |

| SBM, CP 43% | 25 | 24.7 |

| Soybean oil | 1.3 | 1.3 |

| CaCO3 | 7.0 | 7.0 |

| Calcium hydrophosphate (2 water) DCP | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Salt | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| Small peptide | 0 | 0.3 |

| L- Lys-HCL, (98%) | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| DL-Met | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Primix * | 3.0 | 3.0 |

| Total | 100 | 100 |

| ME/(MJ/kg) | 11.51 | 11.51 |

| CP | 15.5 | 15.6 |

| Ca | 3.15 | 3.15 |

| P | 0.43 | 0.43 |

| dLys | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| dMet | 0.35 | 0.35 |

| dCys | 0.28 | 0.28 |

| dM + C | 0.63 | 0.63 |

| Items | SP | CON | SE | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laying rate (%) | 92.47 | 90.38 | 1.71 | 0.064 |

| Abnormal egg rate (%) | 3.92 | 5.04 | 0.61 | 0.013 |

| Egg weight (g) | 64.35 | 63.36 | 4.73 | 0.813 |

| Egg shape index | 1.31 | 1.31 | 0.03 | 0.717 |

| Eggshell strength (Kgf) | 58.74 | 53.53 | 2.31 | 0.022 |

| Albumen height | 8.19 | 6.58 | 1.06 | 0.021 |

| Haugh unit | 85.14 | 82.75 | 5.02 | 0.755 |

| Eggshell thickness (mm) | 0.35 | 0.34 | 0.02 | 0.672 |

| Items | SP | CON | SE | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IgA (g/L) | 2.71 | 2.21 | 0.24 | 0.016 |

| IgG (g/L) | 13.21 | 12.29 | 0.25 | 0.035 |

| SOD (U/L) | 19.17 | 13.06 | 1.28 | 0.027 |

| MDA (mmol/L) | 3.61 | 4.34 | 0.52 | 0.102 |

| GSH (U/L) | 21.22 | 17.86 | 2.23 | 0.024 |

| T-AOC (mmol/L) | 3.82 | 3.51 | 0.47 | 0.322 |

| Hepatic lipase (U/mg) | 170.4 | 163.4 | 1.73 | 0.010 |

| Serum lipoprotein lipase (U/mg) | 6.53 | 6.37 | 0.08 | 0.259 |

| Items | SP | CON | SE | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jejunum | Villus Height (μm) | 719.1 | 708.2 | 6.75 | 0.298 |

| Crypt depth (μm) | 113.2 | 108.1 | 2.79 | 0.136 | |

| V/C | 7.02 | 7.01 | 0.27 | 0.569 | |

| Ileum | Villus Height (μm) | 741.1 | 736.3 | 5.76 | 0.378 |

| Crypt depth (μm) | 103.2 | 101.4 | 3.79 | 0.416 | |

| V/C | 7.21 | 7.26 | 0.37 | 0.529 | |

| Index | SP | CON | SE | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ace | 1938.5 | 1891.9 | 106.23 | 0.556 |

| Chao | 1845.9 | 1807.4 | 57.72 | 0.462 |

| Coverage | 0.991 | 0.988 | 0.007 | 0.441 |

| Shannon | 5.06 | 4.52 | 0.117 | 0.021 |

| Simpson | 0.031 | 0.043 | 0.012 | 0.187 |

| Sobs | 1353.5 | 1336.2 | 26.14 | 0.548 |

| Items | SP | CON | SE | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| g__Bacteroides | 27.12 | 33.32 | 2.75 | 0.042 |

| g__Bacteroidales | 11.29 | 10.42 | 2.72 | 0.711 |

| g__Faecalibacterium | 6.31 | 4.66 | 0.74 | 0.023 |

| g__Phascolarctobacterium | 4.78 | 4.92 | 1.15 | 0.864 |

| g__Ruminococcus | 5.07 | 4.81 | 0.67 | 0.512 |

| g__Lactobacillus | 5.54 | 3.13 | 1.08 | 0.024 |

| g__Desulfovibrio | 2.93 | 2.42 | 0.61 | 0.404 |

| g__Megamonas | 3.51 | 1.43 | 1.40 | 0.142 |

| g__Synergistes | 1.82 | 2.63 | 0.91 | 0.123 |

| others | 32.72 | 33.27 | 1.85 | 0.613 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, Y.; Liao, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Li, L.; Guo, D.; Li, Z. Investigation of Mechanism of Small Peptide Application in Enhancing Laying Performance of Late-Laying Hens Through Bidirectional Liver–Gut Interactions. Animals 2026, 16, 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020164

Li Y, Liao X, Wang X, Wang Y, Liu Q, Li L, Guo D, Li Z. Investigation of Mechanism of Small Peptide Application in Enhancing Laying Performance of Late-Laying Hens Through Bidirectional Liver–Gut Interactions. Animals. 2026; 16(2):164. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020164

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Yuanyuan, Xiaopeng Liao, Xiaoyue Wang, Yiping Wang, Qin Liu, Lizhi Li, Dongsheng Guo, and Zhen Li. 2026. "Investigation of Mechanism of Small Peptide Application in Enhancing Laying Performance of Late-Laying Hens Through Bidirectional Liver–Gut Interactions" Animals 16, no. 2: 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020164

APA StyleLi, Y., Liao, X., Wang, X., Wang, Y., Liu, Q., Li, L., Guo, D., & Li, Z. (2026). Investigation of Mechanism of Small Peptide Application in Enhancing Laying Performance of Late-Laying Hens Through Bidirectional Liver–Gut Interactions. Animals, 16(2), 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020164