A Supervised Deep Learning Model Was Developed to Classify Nelore Cattle (Bos indicus) with Heat Stress in the Brazilian Amazon

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics and Location

2.2. Weather Data

2.3. Animals, Management and Breeding Systems

- Silvopastoral System (SP)—which included trees providing shade and access to water and mineral salt;

- Traditional System (TS)—which did not have trees or shade but did include access to water and mineral salt;

- Integrated System (IS)—which had trees providing shade, water for bathing and drinking, and mineral salt.

2.4. Collection of Respiratory Rate and Rectal Temperature

2.5. Benezra Comfort Index (BTCI)

2.6. Method of Classification of Groups

- In thermal comfort: composed of animals that reached a maximum of 39.3 °C.

- Above thermal comfort: composed of animals that have exceeded this RT threshold.

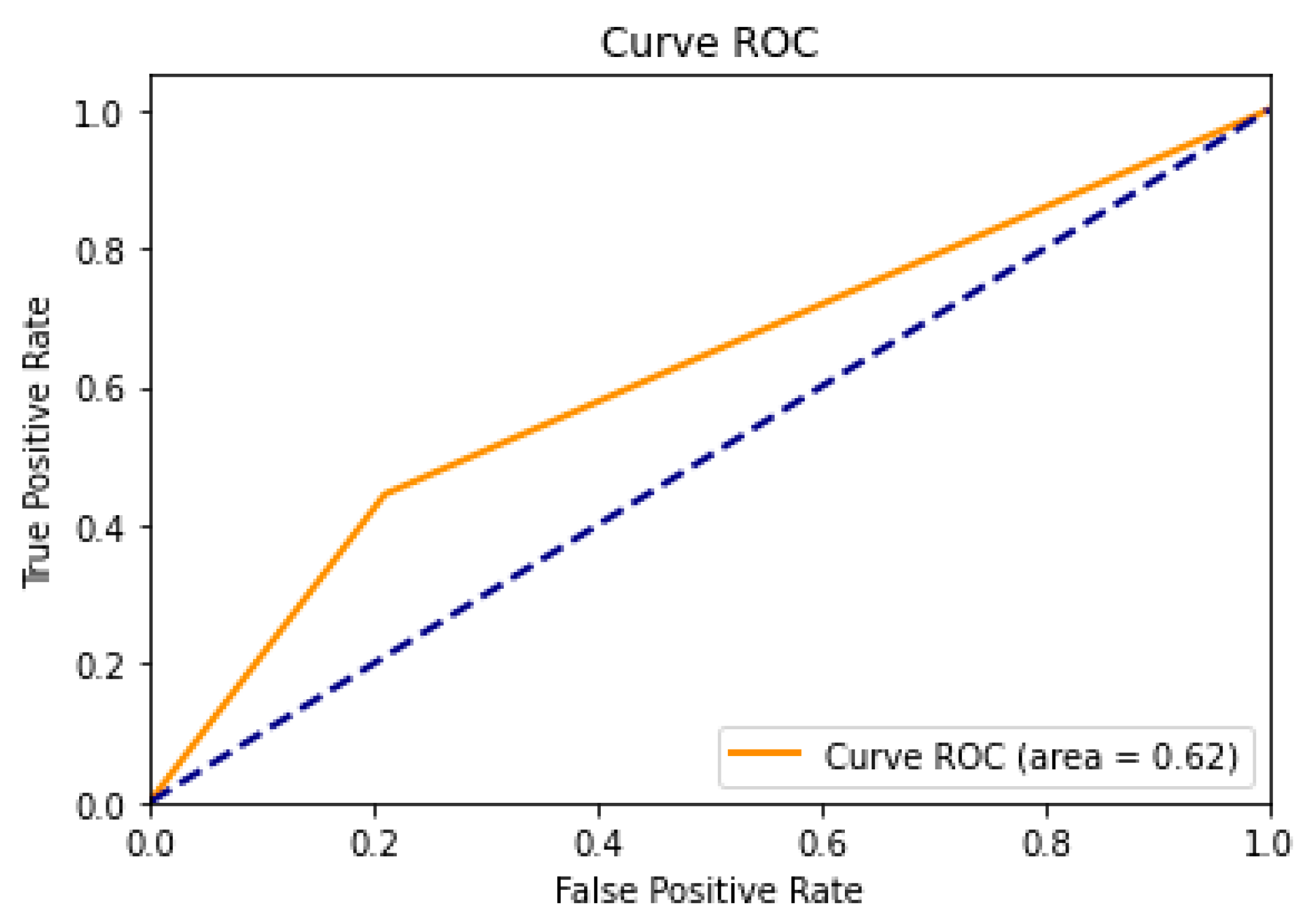

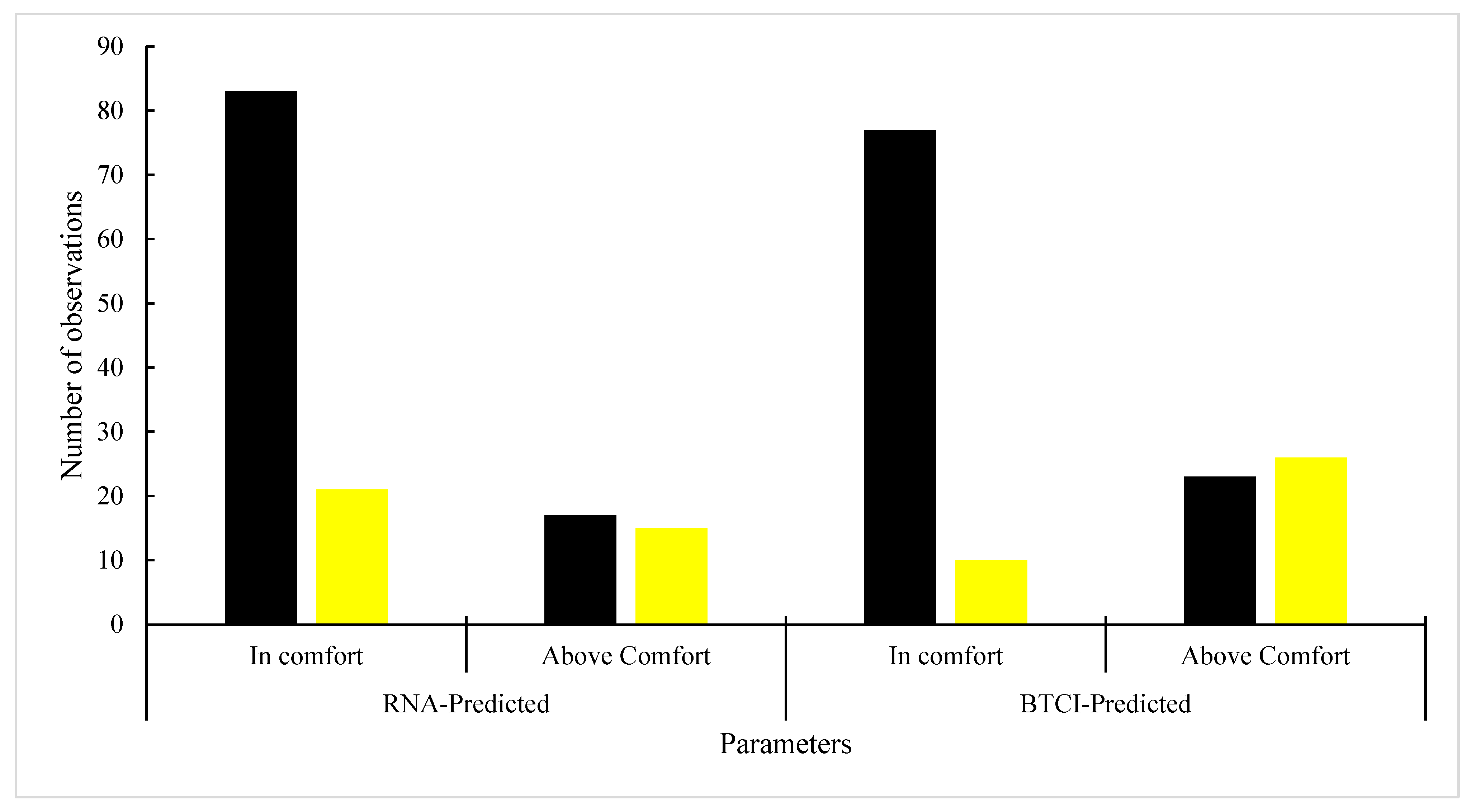

2.7. Model Architecture in Deep Learning

2.8. Canonical Correlation

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Silva, W.C.D.; Silva, J.A.R.D.; Silva, É.B.R.D.; Barbosa, A.V.C.; Sousa, C.E.L.; Carvalho, K.C.D.; Santos, M.R.P.D.; Neves, K.A.L.; Martorano, L.G.; Camargo Júnior, R.N.C.; et al. Characterization of Thermal Patterns Using Infrared Thermography and Thermolytic Responses of Cattle Reared in Three Different Systems during the Transition Period in the Eastern Amazon, Brazil. Animals 2023, 13, 2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, W.C.; da Silva, É.B.R.; Santos, M.R.P.D.; Junior, R.N.C.C.; Barbosa, A.V.C.; da Silva, J.A.R.; Vinhote, J.A.; de Sousa, E.D.V.; de Brito Lourenço Júnior, J. Behavior and thermal comfort of light and dark coat dairy cows in the Eastern Amazon. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 1006093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota-Rojas, D.; Titto, C.G.; Orihuela, A.; Martínez-Burnes, J.; Gómez-Prado, J.; Torres-Bernal, F.; Flores-Padilla, K.; Carvajal-De la Fuente, V.; Wang, D. Physiological and behavioral mechanisms of thermoregulation in mammals. Animals 2021, 11, 1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, W.C.; Printes, O.V.N.; Lima, D.O.; da Silva, É.B.R.; Santos, M.R.P.D.; Júnior, R.N.C.C.; Barbosa, A.V.C.; da Silva, J.A.R.; Silva, A.G.M.E.; Silva, L.K.X.; et al. Evaluation of the temperature and humidity index to support the implementation of a rearing system for ruminants in the Western Amazon. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1198678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felini, R.; Cavallini, D.; Buonaiuto, G.; Bordin, T. Assessing the impact of thermoregulatory mineral supplementation on thermal comfort in lactating Holstein cows. Vet. Anim. Sci. 2024, 24, 100363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulu, D.; Hundessa, F.; Gadissa, S.; Temesgen, T. Review on the influence of water quality on livestock production in the era of climate change: Perspectives from dryland regions. Cogent Food Agric. 2024, 10, 2306726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nzeyimana, J.B.; Fan, C.; Zhuo, Z.; Butore, J.; Cheng, J. Heat stress effects on the lactation performance, reproduction, and alleviating nutritional strategies in dairy cattle, a review. J. Anim. Behav. Biometeorol. 2023, 11, 2023018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idris, M.; Sullivan, M.; Gaughan, J.B.; Keeley, T.; Phillips, C.J.C. Faecal cortisol metabolites, body temperature, and behaviour of beef cattle exposed to a heat load. Animal 2024, 18, 101112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhoads, M.L. Reproductive consequences of whole-body adaptations of dairy cattle to heat stress. Animal 2023, 17, 100847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veissier, I.; Laer, E.V.; Palme, R.; Moons, C.P.H.; Ampe, B.; Sonck, B.; Andanson, S.; Tuyttens, F.A. Heat stress in cows at pasture and benefit of shade in a temperate climate region. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2018, 62, 585–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, W.; Ali, M.; Ahmad, M.; Dilawar, S.; Firdous, A.; Afzal, A. Application of Modern Techniques in Animal Production Sector for Human and Animal Welfare. Turk. J. Agric.-Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 8, 457–463. [Google Scholar]

- Buller, H.; Blokhuis, H.; Lokhorst, K.; Silberberg, M.; Veissier, I. Animal welfare management in a digital world. Animals 2020, 10, 1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ventura, G.; Lorenzi, V.; Mazza, F.; Clemente, G.A.; Iacomino, C.; Bertocchi, L.; Fusi, F. Best farming practices for the welfare of dairy cows, heifers and calves. Animals 2021, 11, 2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadiq, M.B.; Ramanoon, S.Z.; Mansor, R.; Syed-Hussain, S.S.; Mossadeq, W.S. Dairy farmers’ knowledge, awareness and practices regarding bovine lameness in Malaysian dairy farms. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2024, 56, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brcko, C.C.; da Silva, J.A.R.; Garcia, A.R.; Silva, A.G.M.; Martorano, L.G.; Vilela, R.A.; Nahúm, B.d.S.; Barbosa, A.V.C.; da Silva, W.C.; Rodrigues, T.C.G.d.C.; et al. Effects of Climatic Conditions and Supplementation with Palm Cake on the Thermoregulation of Crossbred Buffaloes Raised in a Rotational Grazing System and with Natural Shade in Humid Tropical Regions. Animals 2023, 14, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, U.; Samad, H.; Shehzad, F.; Qayyum, A. Physiological responses of cattle to heat stress. World Appl. Sci. J. 2010, 8, 38–43. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, D.A.D.; Santos, V.M.D.; Oliveira, A.V.D.D.; Souza, C.L.D.; Moreira, G.R.; Rosa, B.L.; Reis, E.M.B.; Queiroz, A.M.D. Seasonality effect on the physiological and productive responses of crossbred dairy cows to the equatorial Amazon climate. Ciência Anim. Bras. 2023, 24, e-73559E. [Google Scholar]

- Blond, B.; Majkić, M.; Spasojević, J.; Hristov, S.; Radinović, M.; Nikolić, S.; Anđušić, L.; Čukić, A.; Marinković, M.D.; Vujanović, B.D.; et al. Influence of Heat Stress on Body Surface Temperature and Blood Metabolic, Endocrine, and Inflammatory Parameters and Their Correlation in Cows. Metabolites 2024, 14, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, J.; McNeill, D.M.; Lisle, A.T.; Phillips, C.J.C. A sampling strategy for the determination of infrared temperature of relevant external body surfaces of dairy cows. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2020, 64, 1583–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittaker, A.L.; Muns, R.; Wang, D.; Martínez-Burnes, J.; Hernández-Ávalos, I.; Casas-Alvarado, A.; Domínguez-Oliva, A.; Mota-Rojas, D. Assessment of Pain and Inflammation in Domestic Animals Using Infrared Thermography: A Narrative Review. Animals 2023, 13, 2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mota-Rojas, D.; Ogi, A.; Villanueva-García, D.; Hernández-Ávalos, I.; Casas-Alvarado, A.; Domínguez-Oliva, A.; Lendez, P.; Ghezzi, M. Thermal Imaging as a Method to Indirectly Assess Peripheral Vascular Integrity and Tissue Viability in Veterinary Medicine: Animal Models and Clinical Applications. Animals 2023, 14, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, I.P.; Gonçalves, P.H.D.; Rodrigues, M.S.; Nascimento, G.B.D.; Baptista, R.S.; Filho, J.R.L.C.; Wolf, A.; Wolf, S.H.G. Infrared thermography for detection of clinical and subclinical mastitis in dairy cattle: Comparison between Girolando and Jersey breeds. Ciência Anim. Bras. 2023, 24, e-76726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghezzi, M.D.; Napolitano, F.; Casas-Alvarado, A.; Hernández-Ávalos, I.; Domínguez-Oliva, A.; Olmos-Hernández, A.; Pereira, A.M. Utilization of Infrared Thermography in Assessing Thermal Responses of Farm Animals under Heat Stress. Animals 2024, 14, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquez, H.P.; Schaefer, A.L.; Bench, C.J. Use of fidget and drinking behaviour in combination with facial infrared thermography for diagnosis of bovine respiratory disease in a spontaneous model. Animal 2024, 18, 101096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.; Sun, F.; Kong, T.; Zhang, W.; Yang, C.; Liu, C. A survey on deep transfer learning. In Artificial Neural Networks and Machine Learning–ICANN 2018, Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Artificial Neural Networks, Rhodes, Greece, 4–7 October 2018; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 270–279. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, B.; Wu, Q.; Yin, X.; Wu, D.; Song, H.; He, D. FLYOLOv3 deep learning for key parts of dairy cow body detection. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2019, 166, 104982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Sun, G.; Zheng, K.; Mazhar, S. Pupil detection based on oblique projection using a binocular camera. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 105754–105765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Kim, D.H.; Lee, S.; Lee, T.; Lee, K.W.; Chang, H.H.; Choi, Y.H. An acute, rather than progressive, increase in temperature-humidity index has severe effects on mortality in laying hens. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 568093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wu, T.; Gao, F.; Charlton, J.R.; Bennett, K.M. Improved small blob detection in 3D images using jointly constrained deep learning and Hessian analysis. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjergji, M.; de Moraes Weber, V.; Silva, L.O.C.; da Costa Gomes, R.; De Araújo, T.L.A.C.; Pistori, H.; Alvarez, M. Deep learning techniques for beef cattle body weight prediction. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Glasgow, UK, 19–24 July 2020; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Psota, E.T.; Luc, E.K.; Pighetti, G.M.; Schneider, L.G.; Fryxell, R.T.; Keele, J.W.; Kuehn, L.A. Desenvolvimento e validação de uma rede neural para detecção automatizada de moscas-dos-chifres em bovinos. Informática Eletrônica Agric. 2021, 180, 105927. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmud, M.S.; Zahid, A.; Das, A.K.; Muzammil, M.; Khan, M.U. A systematic literature review on deep learning applications for precision cattle farming. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 187, 106313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, N.H.; Chlingaryan, A.; Thomson, P.C.; Lomax, S.; Islam, M.A.; Doughty, A.K.; Clark, C.E. A deep learning model to forecast cattle heat stress. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 211, 107932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roopaei, M.; Bergmann, C.; Azemi, A.; Hardyman, K.; Hampton, J. Advancing Cattle Health: AI-Driven Innovations in Lameness Detection and Management. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 14th Annual Computing and Communication Workshop and Conference (CCWC), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 8–10 January 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Köppen, W.; Geiger, R. Klimate der Erde. In Wall-Map 150 cm × 200 cm; Verlag JustusPerthes: Gotha, Germany, 1928; pp. 91–102. [Google Scholar]

- Martorano, L.G.; Vitorino, M.I.; da Silva, B.P.P.C.; Lisboa, L.S.; Sotta, E.D.; Reichardt, K. Climate conditions in the eastern amazon: Rainfall variability in Belem and indicative of soil water deficit. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2017, 12, 1801–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirksen, G.; Gründer, H.D.; Stöber, M. Rosenberger Exame Clínico dos Bovinos, 3rd ed.; Guanabara Koogan: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1993; p. 419. [Google Scholar]

- Python Software Foundation. Python Language Reference, Version 2.7. Available online: http://www.python.org (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- de Sousa, R.V.; Canata, T.F.; Leme, P.R.; Martello, L.S. Development and evaluation of a fuzzy logic classifier for assessing beef cattle thermal stress using weather and physiological variables. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2016, 127, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa, R.V.; da Silva Rodrigues, A.V.; de Abreu, M.G.; Tabile, R.A.; Martello, L.S. Predictive model based on artificial neural network for assessing beef cattle thermal stress using weather and physiological variables. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2018, 144, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neethirajan, S. Artificial intelligence and sensor innovations: Enhancing livestock welfare with a human-centric approach. Hum. -Centric Intell. Syst. 2024, 4, 77–92. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, B.; Tang, W.; Cui, L.; Deng, X. Precision livestock farming research: A global scientometric review. Animals 2023, 13, 2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antanaitis, R.; Džermeikaitė, K.; Šimkutė, A.; Girdauskaitė, A.; Ribelytė, I.; Anskienė, L. Use of Innovative Tools for the Detection of the Impact of Heat Stress on Reticulorumen Parameters and Cow Walking Activity Levels. Animals 2023, 13, 1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, S.F.; Silva, M.C.; Miranda, J.M.; Stilwell, G.; Cortez, P.P. Predictive Models of Dairy Cow Thermal State: A Review from a Technological Perspective. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neethirajan, S. Transforming the adaptation physiology of farm animals through sensors. Animals 2020, 10, 1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepomuceno, G.L.; Cecchin, D.; Damasceno, F.A.; Amaral, P.I.S.; Caproni, V.R.; Ponciano Ferraz, P.F. Compost barn system and its influence on the environment, comfort and welfare of dairy cattle. Comf. Welf. Dairy Cattle 2023, 21, 1233–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, R.M.F.; Façanha, D.A.E.; McManus, C.; Asensio, L.A.B.; da Silva, I.J.O. Intelligent methodologies: An integrated multi-modeling approach to predict adaptive mechanisms in farm animals. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 216, 108502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Singh, B.; Rengarajan, A. Assessing the Temperature Conditions and Behavioral Habits in a Farm to Ensure Cattle Welfare. Rev. Electron. Vet. 2024, 25, 24–31. [Google Scholar]

- Theusme, C.; Macías-Cruz, U.; Castañeda-Bustos, V.; López-Baca, M.A.; García-Cueto, R.O.; Vicente-Pérez, R.; Mellado, M.; Vargas-Villamil, L.; Avendaño-Reyes, L. Holstein heifers in desert climate: Effect of coat color on physiological variables and prediction of rectal temperature. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2023, 55, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontiggia, A.; Münger, A.; Eggerschwiler, L.; Holinger, M.; Stucki, D.; Ammer, S.; Bruckmaier, R.; Dohme-Meier, F.; Keil, N. Behavioural responses related to increasing core body temperature of grazing dairy cows experiencing moderate heat stress. Animal 2024, 18, 101097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mader, T.L.; Gaughan, J.B.; Johnson, L.J.; Hahn, G.L. Tympanic temperature in confined beef cattle exposed to excessive heat load. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2010, 54, 629–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouwknecht, J.A.; Olivier, B.; Paylor, R.E. The stress-induced hyperthermia paradigm as a physiological animal model for anxiety: A review of pharmacological and genetic studies in the mouse. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2007, 31, 41–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shephard, R.W.; Maloney, S.K. A review of thermal stress in cattle. Aust. Vet. J. 2023, 101, 417–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanger, M.E.; Doyle, R.E.; Hinch, G.N.; Lee, C. Sheep exhibit a positive judgement bias and stress-induced hyperthermia following shearing. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2011, 131, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oka, T.; Oka, K. Mechanisms of psychogenic fever. Adv. Neuroimmune Biol. 2012, 3, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čukić, A.; Rakonjac, S.; Djoković, R.; Cincović, M.; Bogosavljević-Bošković, S.; Petrović, M.; Savić, Ž.; Andjušić, L.; Andjelić, B. Influence of heat stress on body temperatures measured by infrared thermography, blood metabolic parameters and its correlation in sheep. Metabolites 2023, 13, 957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.A.; Lomax, S.; Doughty, A.; Islam, M.R.; Jay, O.; Thomson, P.; Clark, C. Automated monitoring of cattle heat stress and its mitigation. Front. Anim. Sci. 2021, 2, 737213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernatchez, L.; Ferchaud, A.L.; Berger, C.S.; Venney, C.J.; Xuereb, A. Genomics for monitoring and understanding species responses to global climate change. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2024, 25, 165–183. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, A.V.; Martello, L.S.; Pacheco, V.M.; de Souza Sardinha, E.J.; Pereira, A.L.V.; de Sousa, R.V. Thermal signature: A method to extract characteristics from infrared thermography data applied to the development of animal heat stress classifier models. J. Therm. Biol. 2023, 115, 103609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Yan, L.; Hou, Z.; Lin, J.; Zhao, Y.; Ji, Z.; Wang, Y. Error Analysis Strategy for Long-term Correlated Network Systems: Generalized Nonlinear Stochastic Processes and Dual-Layer Filtering Architecture. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 33731–33745. [Google Scholar]

- Brown-Brandl, T.M.; Jones, D.D.; Woldt, W.E. Evaluating modelling techniques for cattle heat stress prediction. Biosyst. Eng. 2005, 91, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Julio, Y.F.; Yanagi, T., Jr.; de Fátima Ávila Pires, M.; Aurélio Lopes, M.; Ribeiro de Lima, R. Models for prediction of physiological responses of Holstein dairy cows. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2014, 28, 766–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, V.M.; Sousa, R.V.; Sardinha, E.J.; Rodrigues, A.V.; Brown-Brandl, T.M.; Martello, L.S. Deep learning-based model classifies thermal conditions in dairy cows using infrared thermography. Biosyst. Eng. 2022, 221, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| In Thermal Comfort (n = 452) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average | SD | Lm. | Um. | |

| Rectal Temperature (°C) | 38.75 | 0.33 | 38.72 | 38.79 |

| Respiratory Rate (mpm) | 31.35 | 6.52 | 30.75 | 31.95 |

| Air temperature (°C) | 27.75 | 3.42 | 27.43 | 28.06 |

| Relative Humidity (%) | 59.95 | 15.84 | 58.48 | 61.41 |

| Above Thermal Comfort (n = 224) | ||||

| Average | SD | Lm. | Um. | |

| Rectal Temperature (°C) | 39.56 | 0.20 | 39.53 | 39.59 |

| Respiratory Rate (mpm) | 31.86 | 6.80 | 30.96 | 32.76 |

| Air temperature (°C) | 29.35 | 2.83 | 28.98 | 29.72 |

| Relative Humidity (%) | 55.56 | 16.23 | 53.42 | 57.70 |

| Training Sample (n = 540) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criminators | Average | SD | Min. | Max. |

| Respiratory Rate (mpm) | 31.76 | 6.54 | 20.00 | 60.00 |

| Air Temperature (°C) | 28.31 | 3.26 | 22.10 | 34.00 |

| Relative Humidity (%) | 58.22 | 16.27 | 30.00 | 84.00 |

| Test Sample (n = 136) | ||||

| Average | SD | Min. | Max. | |

| Respiratory Rate (mpm) | 30.57 | 6.84 | 16.00 | 56.00 |

| Air Temperature (°C) | 28.16 | 3.56 | 22.10 | 34.00 |

| Relative Humidity (%) | 59.59 | 15.39 | 32.00 | 84.00 |

| Total Sample Size (n = 676) | ||||

| Average | SD | Min. | Max. | |

| Respiratory Rate (mpm) | 31.52 | 6.62 | 16.00 | 60.00 |

| Air Temperature (°C) | 28.28 | 3.32 | 22.10 | 34.00 |

| Relative Humidity (%) | 58.49 | 16.09 | 30.00 | 84.00 |

| Real | Predicted | |

|---|---|---|

| In Comfort | Above Comfort | |

| In Comfort | 83 | 17 |

| Above Comfort | 21 | 15 |

| Discriminators | Standardized Coefficient of the First | |

|---|---|---|

| Canonical Pair | ||

| Biotic Variables | BV | |

| Rectal Temperature (°C) | 0.9503 | |

| Respiratory Rate (mpm) | 0.2295 | |

| Abiotic Variables | AV | |

| Air Temperature (°C) | 1.0796 | |

| Relative Humidity (%) | 0.1888 | |

| Canonical correlation | ||

| Biotic Variables | BV | AV |

| Rectal Temperature (°C) | 0.97 | 0.34 |

| Respiratory Rate (mpm) | 0.32 | 0.11 |

| Abiotic Variables | AV | BV |

| Air Temperature (°C) | 0.98 | 0.35 |

| Relative Humidity (%) | −0.34 | −0.12 |

| ANN Predicted | BTCI Predicted | |

|---|---|---|

| In Comfort | Above Comfort | |

| In Comfort | 86 | 10 |

| Above Comfort | 1 | 39 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Silva, W.C.d.; Silva, J.A.R.d.; Martorano, L.G.; Silva, É.B.R.d.; Araújo, C.V.d.; Camargo-Júnior, R.N.C.; Neves, K.A.L.; Belo, T.S.; Joaquim, L.A.; Rodrigues, T.C.G.d.C.; et al. A Supervised Deep Learning Model Was Developed to Classify Nelore Cattle (Bos indicus) with Heat Stress in the Brazilian Amazon. Animals 2026, 16, 161. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020161

Silva WCd, Silva JARd, Martorano LG, Silva ÉBRd, Araújo CVd, Camargo-Júnior RNC, Neves KAL, Belo TS, Joaquim LA, Rodrigues TCGdC, et al. A Supervised Deep Learning Model Was Developed to Classify Nelore Cattle (Bos indicus) with Heat Stress in the Brazilian Amazon. Animals. 2026; 16(2):161. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020161

Chicago/Turabian StyleSilva, Welligton Conceição da, Jamile Andréa Rodrigues da Silva, Lucietta Guerreiro Martorano, Éder Bruno Rebelo da Silva, Cláudio Vieira de Araújo, Raimundo Nonato Colares Camargo-Júnior, Kedson Alessandri Lobo Neves, Tatiane Silva Belo, Leonel António Joaquim, Thomaz Cyro Guimarães de Carvalho Rodrigues, and et al. 2026. "A Supervised Deep Learning Model Was Developed to Classify Nelore Cattle (Bos indicus) with Heat Stress in the Brazilian Amazon" Animals 16, no. 2: 161. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020161

APA StyleSilva, W. C. d., Silva, J. A. R. d., Martorano, L. G., Silva, É. B. R. d., Araújo, C. V. d., Camargo-Júnior, R. N. C., Neves, K. A. L., Belo, T. S., Joaquim, L. A., Rodrigues, T. C. G. d. C., Silva, A. G. M. e., & Lourenço-Júnior, J. d. B. (2026). A Supervised Deep Learning Model Was Developed to Classify Nelore Cattle (Bos indicus) with Heat Stress in the Brazilian Amazon. Animals, 16(2), 161. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020161