Enhanced CenterTrack for Robust Underwater Multi-Fish Tracking

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- A multi-fish tracking framework based on CenterTrack is proposed for reconstructing and refining historical features, which can better adapt to dense occlusions and rapid, non-rigid fish motion and improve trajectory stability and reducing identity switches.

- (2)

- Adaptive motion–appearance fusion and occlusion-aware trajectory recovery strategies are introduced to handle unreliable associations caused by fast motion, visual ambiguity, and prolonged occlusions. which can improve tracking robustness in realistic aquaculture environment.

- (3)

- A self-built MF25 multi-fish tracking dataset is constructed, containing annotated video sequences of 75 fish captured in a unified underwater scene. It features diverse motion patterns and complex group interactions, providing frame-level detections and trajectory-level ground truth for systematic evaluation.

- (4)

- Extensive experiments and ablation studies show that the proposed method achieves robust tracking performance, producing trajectories with improved continuity and identity consistency, suitable for downstream behavioral and group-dynamics analysis.

2. Materials and Methods

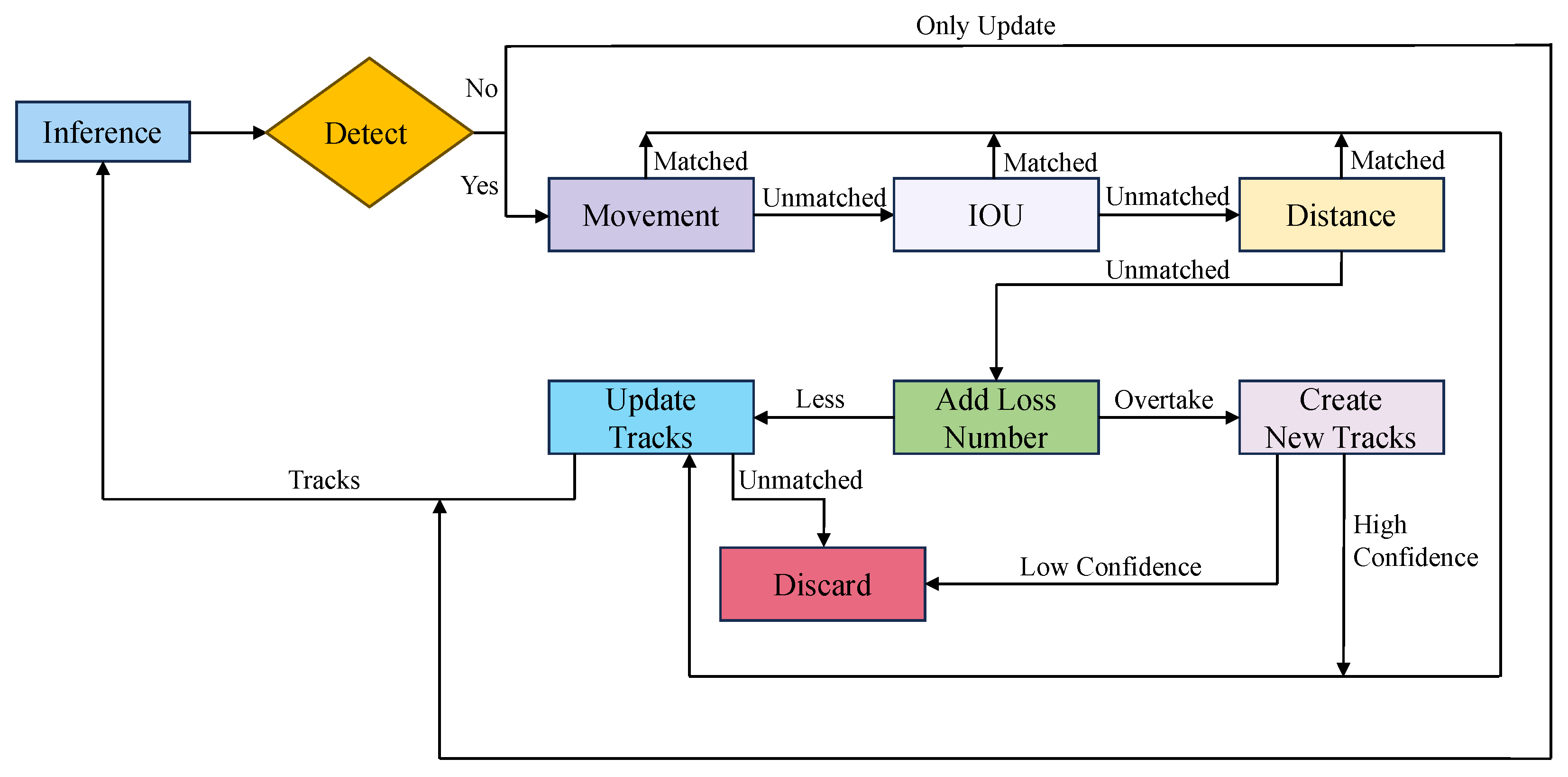

2.1. Framework

2.2. Multi-Scale Attention and Dynamic Weighting

2.3. Occlusion-Aware Head

2.4. Cascade Correspondence Association

| Algorithm 1 Triple-Stage Cascade Matching |

|

2.5. Evaluation Metrics

2.6. Training and Inference

3. Experiments

3.1. DataSet

3.2. Comparative Study

3.3. Ablation Study and Analysis

3.4. Hyperparameter Optimization

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Features and Contributions

4.2. Correlation Between Tracking Accuracy and Activity Estimation

4.3. Limitations and Future Directions

- (1)

- Environmental diversity and domain shift: Experiments were conducted in relatively controlled tank environments that simulate industrial aquaculture. Although these settings capture realistic occlusion and crowding patterns, environmental diversity remains limited. Variations in illumination, water turbidity, camera viewpoints, and background complexity in real production facilities may introduce domain shifts, potentially degrading tracking performance when the model is directly applied without further adaptation.

- (2)

- Identity persistence under long-term occlusion: The proposed tracker maintains short-term visual identities rather than persistent biological identities. When fish leave the field of view or experience prolonged occlusions, identity consistency may be compromised. This limitation is particularly relevant for long-term behavioral or individual-based studies, where identity switches may affect the interpretation of fine-grained behavioral patterns.

- (3)

- Scope of behavioral analysis: The current study primarily focuses on trajectory-based indicators such as activity level and movement length. While these metrics are informative, they do not fully capture complex group dynamics or physiological states. Future work should investigate richer behavioral descriptors and their relationships with fish health, stress, and environmental variables.

- (4)

- Computational constraints and deployment: Although a systematic analysis of computational efficiency across different hardware platforms was not conducted, the proposed framework achieves real-time tracking under the current experimental configuration with 30 FPS input video on a single RTX 4090 GPU. The introduced multi-stage association and motion modeling components are lightweight and do not substantially increase computational complexity compared to the baseline CenterTrack framework. Nevertheless, deployment on resource-constrained edge devices remains challenging due to the deep backbone. Future work will focus on model compression, backbone optimization, and lightweight association strategies to further improve deployment flexibility.

- (5)

- 2D imaging constraints and depth ambiguity: The proposed framework is evaluated under a monocular 2D imaging setup, which inherently limits observability along the depth axis. Fish moving outside the camera field of view or overlapping in depth cannot be continuously tracked, and depth information from the stereo setup was not explicitly exploited in this study. These factors constrain long-term continuous monitoring and should be addressed in future work through multi-view or depth-aware extensions.

4.4. Implications for Aquaculture and Behavioral Analysis

- (1)

- Non-invasive monitoring of fish vitality and adaptability to environmental changes.

- (2)

- Real-time assessment of group behavior and schooling patterns.

- (3)

- Data-driven support for feeding strategies, health management, and tank design.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, Y.; Li, B.; Zhou, X.; Li, D.; Duan, Q. FishTrack: Multi-object tracking method for fish using spatiotemporal information fusion. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 238, 122194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, W.; Qi, Y.; Liu, H.; Li, Z. Dynamic fry counting based on multi-object tracking and one-stage detection. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 209, 107871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Cui, H.; Qu, K.; Zhu, J.; Li, H.; Cui, Z.; Wu, Y. A fish appetite assessment method based on improved ByteTrack and spatiotemporal graph convolutional network. Biosyst. Eng. 2024, 240, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Y.; Sun, B.; Li, D.; Yu, H.; Qin, H.; Liu, H.; Yan, N.; Chen, Y. Recent advances of target tracking applications in aquaculture with emphasis on fish. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 201, 107335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, B.; Si, L.; Liu, C.; Li, D.; Duan, Q. Group activity amount estimation for fish using multi-object tracking. Aquac. Eng. 2025, 110, 102534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, X.; Wang, C.; Liu, W.; Bai, X. SparseTrack: Multi-object tracking by performing scene decomposition based on pseudo-depth. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2025, 35, 4870–4882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, M.; Liu, X.; Liu, H.; Zhao, J.; Li, D.; Wang, W. Fish tracking, counting, and behaviour analysis in digital aquaculture: A comprehensive survey. Rev. Aquac. 2025, 17, 13001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, C.; Cui, M.; Yin, J.; Gu, H.; Ouyang, T.; Feng, J.; Zeng, L. Enhanced deep OC-SORT with YOLOv8-seg for robust fry tracking and behavior analysis in aquaculture. Aquaculture 2025, 610, 742887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tan, H.; Deng, Y.; Zhou, D.; Zhu, M. Hypoxia monitoring of fish in intensive aquaculture based on underwater multi-target tracking. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 232, 110127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S. Sonar image target detection based on deep learning. Math. Probl. Eng. 2022, 2022, 5294151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, L.; Wang, Y.; Feng, X.; Zhao, X.; Sun, M. Zebrafishtracker3D: A 3D skeleton tracking algorithm for multiple zebrafish based on particle matching. ISA Trans. 2024, 151, 363–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Bao, E.; Wen, Y.; Zhu, S.; Ye, Z.; Zhao, J. Behavioral spatial-temporal characteristics-based appetite assessment for fish school in recirculating aquaculture systems. Aquaculture 2021, 545, 737215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, M.; Huo, Y.; Tian, Q.; Zhao, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, R.; Xue, L.; Wang, H. FMRFT: Fusion Mamba and DETR for query time sequence intersection fish tracking. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 237, 110742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folkman, L.; Vo, Q.L.; Johnston, C.; Stantić, B.; Pitt, K.A. A computer vision method to estimate ventilation rate of Atlantic salmon in sea fish farms. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.19719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Høgstedt, E.B.; Schellewald, C.; Mester, R.; Stahl, A. Automated computer vision-based individual salmon (Salmo salar) breathing rate estimation (SaBRE) for improved state observability. Aquaculture 2025, 595, 741535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khiem, N.M.; Van Thanh, T.; Dung, N.H.; Takahashi, Y. A novel approach combining YOLO and DeepSORT for detecting and counting live fish in natural environments through video. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0323547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abangan, A.S.; Kopp, D.; Faillettaz, R. Artificial intelligence for fish behavior recognition: Advances and applications. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1010761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Koltun, V.; Krähenbühl, P. Tracking objects as points. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2020, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Winkler, J.; Badri-Hoeher, S.; Barkouch, F. Activity segmentation and fish tracking from sonar videos by combining artifacts filtering and a Kalman approach. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 96522–96529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandimalla, V.; Richard, M.; Smith, F.; Quirion, J.; Torgo, L.; Whidden, C. Automated Detection, Classification and Counting of Fish in Fish Passages with Deep Learning. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 8, 823173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Wang, D.; Shelhamer, E.; Darrell, T. Deep layer aggregation. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1707.06484. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.Y.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Dollár, P. Focal loss for dense object detection. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2999–3007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Sun, X.; Meng, Y.; Liang, J.; Wu, F.; Li, J. Dice loss for data-imbalanced NLP tasks. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; Online, 5–10 July 2020, Jurafsky, D., Chai, J., Schluter, N., Tetreault, J., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luiten, J. TrackEval. 2020. Available online: https://github.com/JonathonLuiten/TrackEval (accessed on 1 January 2026).

- Luiten, J.; Osep, A.; Dendorfer, P.; Torr, P.; Geiger, A.; Leal-Taixé, L.; Leibe, B. HOTA: A higher order metric for evaluating multi-object tracking. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2020, 129, 548–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bewley, A.; Ge, Z.; Ott, L.; Ramos, F.; Upcroft, B. Simple online and realtime tracking. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Phoenix, AZ, USA, 25–28 September 2016; pp. 3464–3468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojke, N.; Bewley, A. Deep cosine metric learning for person re-identification. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Lake Tahoe, NV, USA, 12–15 March 2018; pp. 748–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojke, N.; Bewley, A.; Paulus, D. Simple online and realtime tracking with a deep association metric. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1703.07402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, P.; Jiang, Y.; Yu, D.; Weng, F.; Yuan, Z.; Luo, P.; Liu, W.; Wang, X. ByteTrack: Multi-object tracking by associating every detection box. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2022, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, J.; Pang, J.; Weng, X.; Khirodkar, R.; Kitani, K. Observation-centric SORT: Rethinking SORT for robust multi-object tracking. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 9686–9696. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, F.; Dong, B.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, T.; Zhang, X.; Wei, Y. MOTR: End-to-end multiple-object tracking with transformer. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2022, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.; Wang, X.; Zeng, W.; Liu, W. FairMOT: On the fairness of detection and re-identification in multiple object tracking. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2021, 129, 3069–3087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Ban, Y.; Delorme, G.; Gan, C.; Rus, D.; Alameda-Pineda, X. TransCenter: Transformers with dense representations for multiple-object tracking. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2103.15145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, P.; Cao, J.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, R.; Xie, E.; Yuan, Z.; Wang, C.; Luo, P. TransTrack: Multiple-object tracking with transformer. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2012.15460. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, H.; Liu, Q.; Liang, X.; Xiao, X. TPTrack: Strengthening tracking-by-detection methods from tracklet processing perspectives. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2024, 114, 109078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Yu, X.; An, D.; Ning, X.; Liu, J.; Tiwari, P. Uniformity and deformation: A benchmark for multi-fish real-time tracking in the farming. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 264, 125653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Yin, T.; Koltun, V.; Krähenbühl, P. Global Tracking Transformers. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 8771–8780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandler, M.; Howard, A.; Zhu, M.; Zhmoginov, A.; Chen, L.C. MobileNetV2: Inverted residuals and linear bottlenecks. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1801.04381. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ID | Name | Image Size | Sequence Length | Frame Rate | Format |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Severely Deformed-01 | 1920 × 1080 pixels | 177 | 30 | PNG |

| 2 | Severely Deformed-02 | 1920 × 1080 pixels | 259 | 30 | PNG |

| 3 | Multi-Density-01 | 1920 × 1080 pixels | 265 | 30 | PNG |

| 4 | Multi-Density-02 | 1920 × 1080 pixels | 193 | 30 | PNG |

| 5 | Severe Occlusion-01 | 1920 × 1080 pixels | 247 | 30 | PNG |

| 6 | Normal-01 | 1920 × 1080 pixels | 535 | 30 | PNG |

| 7 | Normal-02 | 1920 × 1080 pixels | 601 | 30 | PNG |

| Method | IDF1 (%) | IDP (%) | IDR (%) | MOTA (%) | MOTP | MT | ML |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SORT | 51.5 | 94.8 | 35.3 | 35.6 | 0.18 | 4 | 36 |

| DeepSORT | 52.3 | 94.3 | 36.2 | 35.8 | 0.20 | 8 | 33 |

| ByteTrack | 52.2 | 94.3 | 36.1 | 35.7 | 0.20 | 8 | 34 |

| OCSORT | 49.7 | 95.6 | 33.6 | 33.6 | 0.18 | 3 | 39 |

| FairMOT | 47.8 | 88.0 | 32.9 | 33.5 | 0.24 | 6 | 35 |

| CenterTrack | 75.5 | 78.3 | 73.0 | 83.1 | 0.19 | 51 | 2 |

| TransCenter | 74.0 | 76.4 | 71.9 | 84.6 | 0.19 | 52 | 1 |

| TransTrack | 67.3 | 68.8 | 65.9 | 78.7 | 0.19 | 50 | 1 |

| MOTR | 75.6 | 83.5 | 69.1 | 79.4 | 0.20 | 20 | 14 |

| TPTrack | 54.1 | 94.6 | 37.8 | 37.7 | 0.18 | 9 | 33 |

| Ours | 82.5 | 84.7 | 80.4 | 85.8 | 0.19 | 55 | 1 |

| Method | HOTA (%) | DetA (%) | AssA (%) | MOTA (%) | IDF1 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SORT | 32.8 | 56.2 | 19.3 | 66.7 | 30.6 |

| DeepSORT | 25.6 | 61.3 | 10.8 | 69.6 | 21.5 |

| ByteTrack | 35.6 | 52.2 | 24.8 | 56.4 | 38.1 |

| FairMOT | 16.3 | 29.0 | 9.4 | 31.4 | 15.5 |

| CenterTrack | 27.0 | 74.3 | 11.0 | 69.1 | 39.1 |

| TransTrack | 33.5 | 76.3 | 16.5 | 71.3 | 41.9 |

| GTR | 30.9 | 49.8 | 19.4 | 60.1 | 32.9 |

| OCSORT | 39.6 | 55.3 | 28.4 | 70.8 | 46.7 |

| TPTrack | 33.8 | 58.2 | 21.8 | 54.1 | 48.6 |

| Ours | 29.5 | 77.3 | 13.4 | 72.5 | 42.4 |

| Method | IDF1 (%) | IDP (%) | IDR (%) | MOTA (%) | MOTP (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DLA34 | 82.5 | 84.7 | 80.4 | 85.8 | 0.19 |

| DLA60 | 81.3 | 83.8 | 79.0 | 82.9 | 0.20 |

| DLA102 | 78.3 | 80.5 | 76.3 | 82.2 | 0.20 |

| MobilenetV2 | 80.6 | 81.0 | 80.2 | 78.8 | 0.21 |

| ResNet | 79.4 | 80.1 | 77.5 | 79.2 | 0.21 |

| Method | IDF1 (%) | IDP (%) | IDR (%) | MOTA (%) | MOTP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CenterTrack | 75.5 | 78.3 | 73.0 | 83.1 | 0.19 |

| +MADW | 78.8 | 81.6 | 76.3 | 83.9 | 0.20 |

| +OAHead | 79.0 | 81.8 | 76.3 | 81.7 | 0.20 |

| +CCA | 78.4 | 79.6 | 77.1 | 83.7 | 0.20 |

| +MADW + OAHead | 79.8 | 81.9 | 77.8 | 85.0 | 0.20 |

| +MADW + OAHead + CCA | 82.5 | 84.7 | 80.4 | 85.8 | 0.19 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, J.; Lin, M.; Cheng, Z.; Yang, R.; Huang, Q. Enhanced CenterTrack for Robust Underwater Multi-Fish Tracking. Animals 2026, 16, 156. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020156

Wang J, Lin M, Cheng Z, Yang R, Huang Q. Enhanced CenterTrack for Robust Underwater Multi-Fish Tracking. Animals. 2026; 16(2):156. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020156

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Jinfeng, Mingrun Lin, Zhipeng Cheng, Renyou Yang, and Qiong Huang. 2026. "Enhanced CenterTrack for Robust Underwater Multi-Fish Tracking" Animals 16, no. 2: 156. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020156

APA StyleWang, J., Lin, M., Cheng, Z., Yang, R., & Huang, Q. (2026). Enhanced CenterTrack for Robust Underwater Multi-Fish Tracking. Animals, 16(2), 156. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020156