An Integrative Genetic Strategy for Identifying Causal Genes at Quantitative Trait Loci in Chickens

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Gene Prioritization

2.1. Conventional Methods

2.2. New Integrated Genetic Method

3. Causal Gene Identification

3.1. Causal Analysis

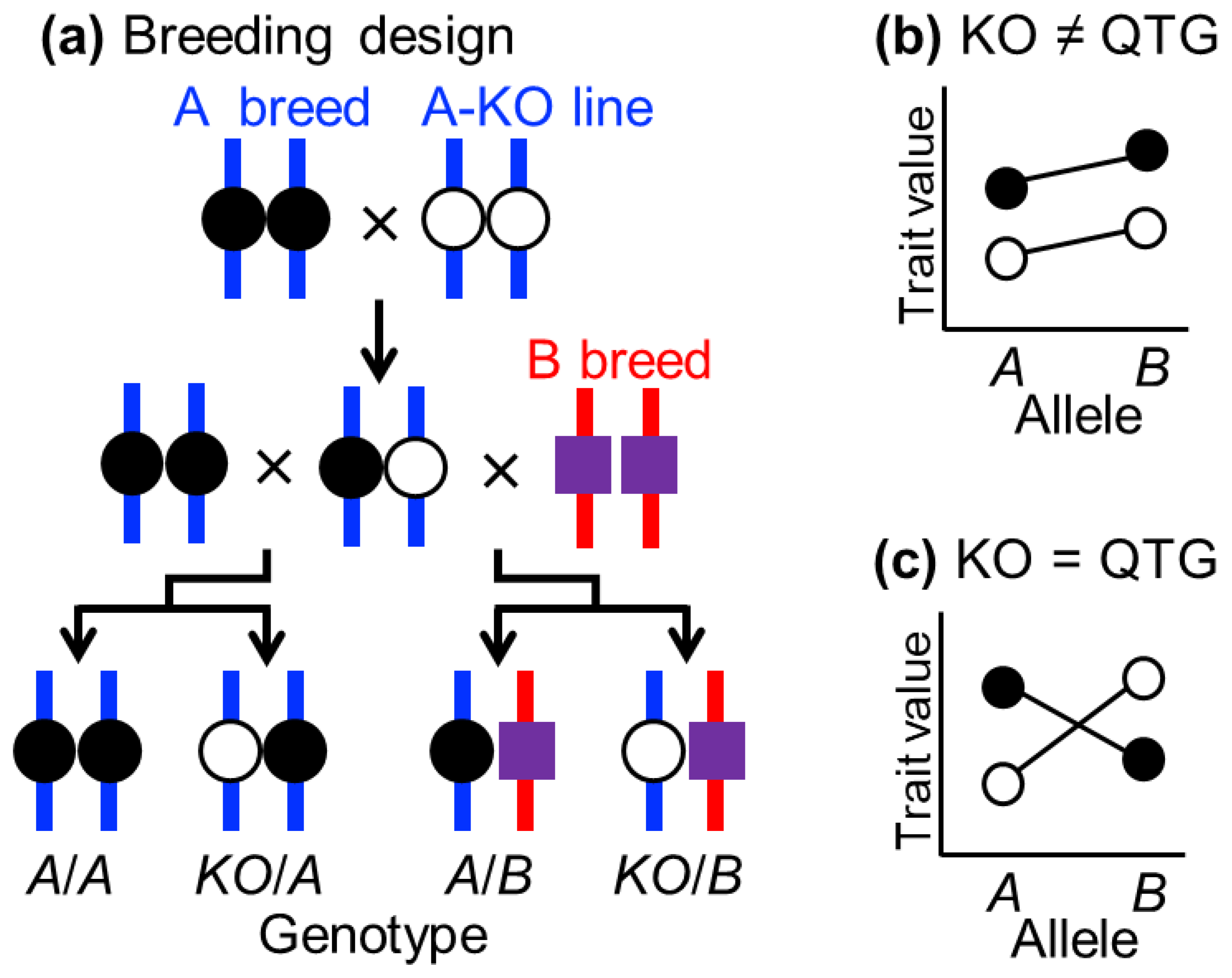

3.2. Quantitative Complementation Test

4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| QTL | quantitative trait locus |

| GWAS | genome-wide association study |

| LD | linkage disequilibrium |

| eQTL | expression QTL |

| RT-qPCR | reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction |

| NAG | Nagoya |

| WL | White Leghorn |

| DEG | differentially expressed gene |

| AIL | advanced intercross line |

| WGCNA | weighted gene co-expression network analysis |

| ENO1 | enolase 1, (alpha) |

| ADH1 | alcohol dehydrogenase 1C (class I), gamma polypeptide |

| ASAH1 | N-acylsphingosine amidohydrolase (acid ceramidase) 1 |

| ADH1C | alcohol dehydrogenase 1C (class I), gamma polypeptide |

| PIK3CD | phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit delta |

| WISP1 | WNT1 inducible signaling pathway protein 1 |

| AKT1 | AKT serine/threonine kinase 1 |

| PANK3 | pantothenate kinase 3 |

| C1QTNF2 | C1q and TNF-related 2 |

| ChickenGTEx | Chicken Genotype-Tissue Expression |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| chCADD | chicken Combined Annotation–Dependent Depletion |

| IGFBP2 | insulin-like growth factor binding protein 2 |

| IGFBP5 | insulin-like growth factor binding protein 5 |

| TWAS | Transcriptome-Wide Association Studies |

| SNP | Single-nucleotide polymorphism |

| CI | confidence interval |

| PCA | principal component analysis |

| PC1 | the first principal component |

| ANOVA | analysis of variance |

| NPY5R | neuropeptide Y receptor Y5 |

| CIT | Causal Inference Test |

| QCT | Quantitative Complementation Test |

| KO | knockout |

| QTG | quantitative trait gene |

| Hcn1 | hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated potassium channel 1 |

| Ly75 | lymphocyte antigen 75 |

References

- Miles, C.; Wayne, M. Quantitative trait locus (QTL) analysis. Nat. Educ. 2008, 1, 208. [Google Scholar]

- Mackay, T. The genetic architecture of quantitative traits. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2001, 35, 303–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keane, T.M.; Goodstadt, L.; Danecek, P.; White, M.A.; Wong, K.; Yalcin, B.; Heger, A.; Agam, A.; Slater, G.; Goodson, M.; et al. Mouse genomic variation and its effect on phenotypes and gene regulation. Nature 2011, 477, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albert, F.W.; Kruglya, L. The role of regulatory variation in complex traits and disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2015, 16, 197–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, A. A strategy for identifying quantitative trait genes using gene expression analysis and causal analysis. Genes 2017, 8, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visscher, P.M.; Wray, N.R.; Zhang, Q.; Sklar, P.; McCarthy, M.I.; Brown, M.A.; Yang, J. 10 Years of GWAS discovery: Biology, function, and translation. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2017, 101, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Zou, D.; Chu, Q.; Zhan, B.; Wang, R.; Guan, D.; Wang, W.; Feng, X.; Li, X.; Zhu, X.; et al. The ChickenGTEx portal: A pan-tissue catalogue of regulatory variants shaping transcriptomic and phenotypic diversity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, T.; Song, L.; Guo, Y.; Chen, C.; Yang, J. From genetic associations to genes: Methods, applications, and challenges. Tred. Genet. 2025, 40, 642–667. [Google Scholar]

- Gamazon, E.R.; Wheeler, H.E.; Shah, K.P.; Mozaffari, S.V.; Aquino-Michaels, K.; Carroll, R.J.; Eyler, A.E.; Denny, J.C.; Consortium, G.; Nicolae, D.L.; et al. A gene-based association method for mapping traits using reference transcriptome data. Nat. Genet. 2015, 47, 1091–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Diao, L.; Han, L. A multi-omics perspective of quantitative trait loci in precision medicine. Trends Genet. 2020, 36, 318–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Teng, J.; Lin, Q.; Bai, Z.; Liu, S.; Guan, D.; Li, B.; Gao, Y.; Hou, Y.; Gong, M.; et al. The farm animal genotype-tissue expression (FarmGTEx) project. Nat. Genet. 2025, 57, 786–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochiai, T.; Sakaguchi, M.; Kawakami, S.I.; Ishikawa, A. Identification of candidate genes responsible for innate fear behavior in the chicken. G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 2023, 13, jkac316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makino, K.; Ishikawa, A. Genetic identification of Ly75 as a novel quantitative trait gene for resistance to obesity in mice. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 17658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Li, C.; Luo, C.; Bai, Z.; Shu, D.; Chen, P.; Ren, J.; Song, R.; Fang, L.; Qu, H.; et al. Mapping the regulatory genetic landscape of complex traits using a chicken advanced intercross line. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 5841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Yuan, P.; Li, S.; Li, H.; Zhai, B.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Gu, J.; Li, H.; Tian, Y.; et al. Genetic architecture and key regulatory genes of fatty acid composition in Gushi chicken breast muscle determined by GWAS and WGCNA. BMC Genom. 2023, 24, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, D.; Bai, Z.; Zhu, X.; Zhong, C.; Hou, Y.; Zhu, D.; The ChickenGTEx Consortium; Li, H.; Lan, F.; Diao, S.; et al. Genetic regulation of gene expression across multiple tissues in chickens. Nat. Genet. 2025, 57, 1298–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, M.; Wu, Y.; Shen, J.; Pan, A.; Zhang, H.; Sun, J.; Liang, Z.; Huang, T.; Du, J.; Pi, J. Genome-wide association study of egg production traits in Shuanglian chickens using whole genome sequencing. Genes 2023, 14, 2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Gu, S.; Zhong, C.; An, L.; Shan, M.; Damas, J.; et al. An atlas of regulatory elements in chicken: A resource for chicken genetics and genomics. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eade1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kianpoor, S.; Ehsani, A.; Torshizi, R.V.; Masoudi, A.A.; Bakhtiarizadeh, M.R. Unlocking the genetic code: A comprehensive genome-wide association study and gene set enrichment analysis of cell-mediated immunity in chickens. BMC Genom. 2025, 26, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derks, M.F.L.; Megens, H.J.; Bosse, M.; Visscher, J.; Peeters, K.; Bink, M.C.A.M.; Vereijken, A.; Gross, C.; de Ridder, D.; Reinders, M.J.T.; et al. A survey of functional genomic variation in domesticated chickens. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2018, 50, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groß, C.; Bortoluzzi, C.; de Ridder, D.; Megens, H.-J.; Groenen, M.A.M.; Reinders, M.; Bosse, M. Prioritizing sequence variants in conserved non-coding elements in the chicken genome using chCADD. PLoS Genet. 2020, 16, e1009027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, L.; Bai, X.; Zhao, L.; Zhou, J.; Chang, C.; Li, X.; Cao, Z.; Li, Y.; Luan, P.; Li, H.; et al. Integrative 3D genomics with multi-omics analysis and functional validation of genetic regulatory mechanisms of abdominal fat deposition in chickens. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 9274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davasi, A.; Soller, M. Advanced intercross lines, an experimental population for fine genetic mapping. Genetics 1995, 141, 1199–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, M.; Chen, K.; Zhang, S.; Tian, M.; Shen, Y.; Cao, C.; Gu, N. Multiome-wide association studies: Novel approaches for understanding diseases. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2024, 22, qzae077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, C.; Li, X.; Guan, D.; Zhang, B.; Wang, X.; Qu, L.; Zhou, H.; Fang, L.; Sun, C.; Yang, N. Age-dependent genetic architectures of chicken body weight explored by multidimensional GWAS and molQTL analyses. J. Genet. Genom. 2024, 51, 1423–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darvasi, A.; Soller, M. Selective DNA pooling for determination of linkage between a molecular marker and a quantitative trait locus. Genetics 1994, 138, 1365–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdavi, K.; Zendehdel, M.; Zarei, H.Z. Neuropeptide Y: An undisputed central simulator of avian appetite. J. Poult. Sci. Avian Dis. 2024, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singanwad, P.; Tatode, A.; Qutub, M.; Taksande, B.; Umekar, M.; Trivedi, R.; Premchandani, T. Neuropeptide Y as a multifaceted modulator of neuroplasticity, Neuroinflammation, and HPA axis dysregulation: Perceptions into treatment-resistant depression. Neuropeptides 2025, 112, 102538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuta, A.; Ishikawa, A. New candidate genes for a chicken pectoralis muscle weight QTL identified by a hypothesis-free integrative genetic approach. Genes 2026, 17, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekula, P.; del Greco, M.F.; Pattaro, C.; Köttgen, A. Mendelian randomization as an approach to assess causality using observational data. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2016, 27, 3253–3265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C.; Lee, B.; Shen, L.; Long, Q. Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging initiative; Alzheimer’s Disease Metabolomics Consortium. Integrating multi-omics summary data using a Mendelian randomization framework. Brief. Bioinform. 2022, 23, bbac376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, S.L.A.; Luo, S.; Iwagami, M.; Goto, A. Introduction to Mendelian randomization. Ann. Clin. Epidemiol. 2025, 7, 27–37, Erratum in Ann. Clin. Epidemiol. 2025, 7, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millstein, J.; Zhang, B.; Zhu, J.; Schadt, E.E. Disentangling molecular relationships with a causal inference test. BMC Genet. 2009, 10, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rikke, B.A.; Johnson, T.E. Towards the cloning of genes underlying murine QTLs. Mamm. Genome 1998, 9, 963–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.B.; Chen, R.; LaPierre, N.; Chen, Z.; Mefford, J.; Marcus, E.; Marcus, E.; Heffel, M.G.; Soto, D.C.; Ernst, J.; et al. Complementation testing identifies genes mediating effects at quantitative trait loci underlying fear-related behavior. Cell Genom. 2024, 4, 100545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method | Main Approach | Advantage | Limitation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Position-based prioritization | Fine mapping of QTL/GWAS regions; identification of nearest genes or those within LD blocks | Simple and straightforward; directly links genomic regions to genes | Difficult to narrow down to a single causal gene; labor- and cost-intensive | [14] |

| Expression-based prioritization | eQTL analysis; differentially expressed genes (DEGs); co-expression (e.g., WGCNA 1) | Links gene expression to traits; provides tissue-specific insights | Requires RNA from the same population; sensitive to tissue environment; resource- and cost-intensive | [15,16] |

| Functional annotation | GO/KEGG 2 enrichment; tissue-specific expression | Provides biological context and functional clues | May overlook poorly annotated or non-coding genes; broad or indirect terms | [17,18,19] |

| Coding variant prediction | In silico prediction of functional impact of nonsynonymous variants using tools such as SIFT 3 or PROVEAN 4 | Identifies potentially damaging coding variants within candidate genes | Limited to coding regions; may miss non-coding effects | [20] |

| Non-coding variant prediction | Annotation of regulatory regions using chCADD 5 or eQTL | Prioritizes non-coding regulatory variants affecting gene expression | Dependent on available datasets; regulatory mechanisms may differ by tissue | [7,18,21] |

| Integrative analysis | Combines QTL mapping, transcriptomics (e.g., TWAS 6) | Enables identification of candidate genes and regulatory mechanisms | Computationally intensive; requires large and well-matched datasets | [22] |

| Step | Methods | Materials | Objective |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | QTL remapping | SNP markers and phenotypic data from the segregating F2 mapping population | Refine the QTL 95% confidence interval (CI) with higher precision |

| 2 | RNA-seq analysis | RNA from three F2 individuals with extreme (top and bottom) phenotypes | Identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) within the CI |

| 3 | RT-qPCR validation | RNA from parental breeds and F1 individuals (n = 10 each) | Validate DEG expression patterns in populations different from the population used in RNA-seq analysis |

| 4 | Haplotype frequency analysis | Haplotypes from two extreme F2 groups (n = 20 each) | Compare haplotype frequencies of validated DEGs between groups; use haplotype frequencies as a trait distinct from gene expression for validation |

| 5 | Association analysis | Gene expression data from the two extreme groups | Test expression differences between groups; validate DEG expression patterns in RNA-seq analysis |

| 6 | Conditional correlation analysis | Gene expression, diplotypes, and phenotypes from the two extreme groups | Assess expression–phenotype correlation conditioned on diplotypes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ishikawa, A. An Integrative Genetic Strategy for Identifying Causal Genes at Quantitative Trait Loci in Chickens. Animals 2026, 16, 155. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020155

Ishikawa A. An Integrative Genetic Strategy for Identifying Causal Genes at Quantitative Trait Loci in Chickens. Animals. 2026; 16(2):155. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020155

Chicago/Turabian StyleIshikawa, Akira. 2026. "An Integrative Genetic Strategy for Identifying Causal Genes at Quantitative Trait Loci in Chickens" Animals 16, no. 2: 155. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020155

APA StyleIshikawa, A. (2026). An Integrative Genetic Strategy for Identifying Causal Genes at Quantitative Trait Loci in Chickens. Animals, 16(2), 155. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020155