1. Introduction

Eels are highly esteemed in aquaculture owing to their significant market value, robust survival rates, high productivity, and extensively researched disease profiles. Among the 19 recognized species of

Anguilla, the Japanese eel,

Anguilla japonica, and the European eel,

A. anguilla, hold the greatest economic and cultural significance, being primarily cultivated in East Asia (notably Japan, Taiwan, and China) and Europe (particularly Italy and the Netherlands), respectively [

1]. Despite their significance, the juvenile populations of

A. anguilla and

A. japonica have declined dramatically in recent decades, as reported by Pike et al. [

2] and Hakoyama et al. [

3,

4]. Consequently, the urgent need to develop techniques for the large-scale production of eel larvae or to identify alternative

Anguilla species for

A. japonica aquaculture has become increasingly apparent.

The short-finned eel,

A. bicolor, is a tropical catadromous species of considerable economic significance in Southeast Asian fisheries. Recognized as a viable alternative to

A. japonica for aquaculture,

A. bicolor is highly valued for its texture and flavor, which align with market preferences and enhance its commercial appeal [

5]. Beyond its culinary desirability,

A. bicolor exhibits a broader geographic distribution than most of the 19 recognized species and subspecies within the genus

Anguilla [

6,

7]. Currently, two subspecies of

A. bicolor are distinguished:

A. bicolor bicolor and

A. bicolor pacifica [

6,

8,

9]. While these subspecies share similar morphological traits, their geographical distributions are distinct.

A. bicolor bicolor is restricted to the Indian Ocean, whereas

A. bicolor pacifica is distributed throughout the Indo-Pacific, encompassing the Western Pacific Ocean and the surrounding waters of northern Indonesia, China, Vietnam, the Philippines, Borneo, Sulawesi, and New Guinea [

6,

7,

8]. Notably,

A. bicolor pacifica is characterized by a relatively stable effective population size [

10] and therefore may represent a promising candidate species to help mitigate the current shortage of

A. japonica glass eel resources for aquaculture. This extensive distribution highlights the ecological and commercial significance of

A. bicolor pacifica across diverse aquatic ecosystems.

In eel aquaculture, the rearing phase commences when glass eels are collected from estuarine regions. A notable challenge during this phase is the prevalent size heterogeneity among eels [

11,

12], which can significantly impact the efficiency of farming operations. This variability necessitates substantial labor investment in size-grading procedures to minimize disparities [

13,

14]. Size heterogeneity often leads to a phenomenon known as the hierarchical size effect, wherein dominant individuals monopolize access to feed resources, inhibiting the feeding opportunities of smaller conspecifics. As a result, larger eels are typically able to consume more feed, exhibit accelerated growth rates, and ultimately achieve greater body weights compared to their smaller counterparts [

15].

Size variation among aquaculture animals is influenced by a multitude of factors, including water quality, stocking density, territorial behavior, and nutritional availability [

16,

17]. These factors interact in intricate ways, shaping growth rates, feed conversion efficiency, and overall health, ultimately resulting in size heterogeneity within a population. Nevertheless, even under identical rearing conditions, growth performance can be further modulated by intrinsic factors, such as the central nervous system, and endocrinological and neuroendocrinological regulatory pathways [

18]. These internal mechanisms play pivotal roles in mediating physiological responses to environmental cues, thereby contributing to individual variability in growth outcomes. Intestinal microbiota is known a new possible internal factor as it is gradually recognized that it plays very important role in the health and growth of the host [

19,

20]. Sun et al. [

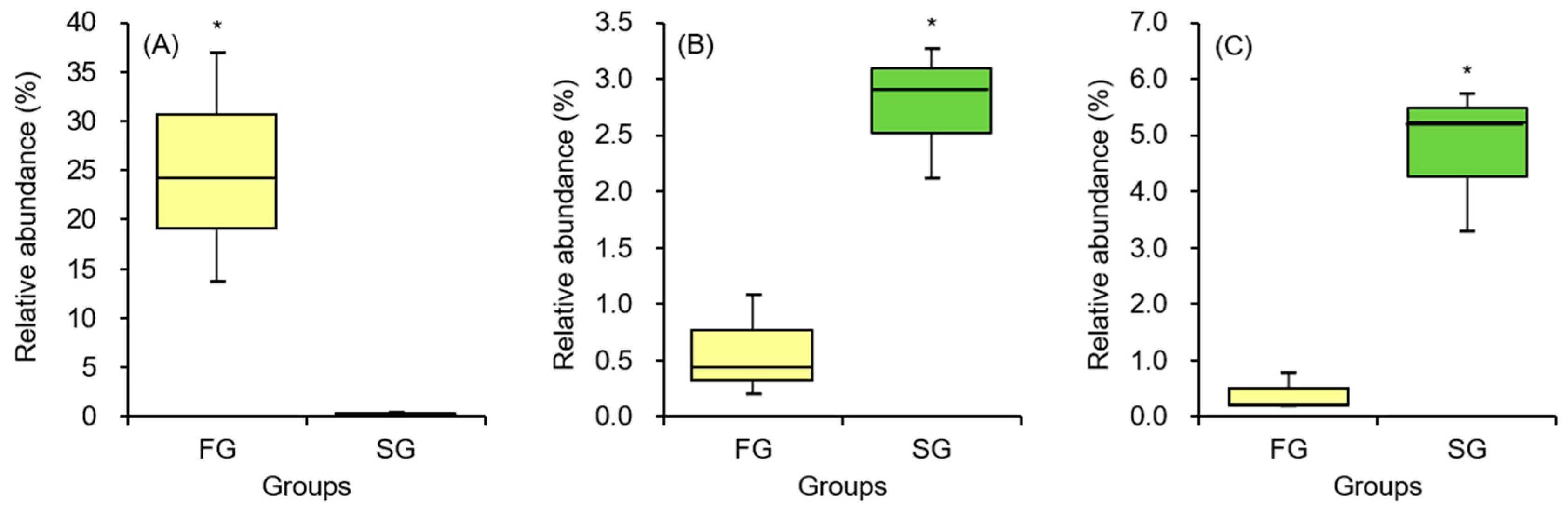

21] conducted a comprehensive investigation into the gut microbiota differences between slow-growing (SG) and fast-growing (FG) juvenile

Epinephelus coioides. Their findings revealed a higher abundance of

Vibrio species in SG groupers, whereas the gut microbiota of FG groupers was predominantly enriched with beneficial bacterial species, including

Bacillus pumilus,

B. clausii, and

Psychrobacter sp., which were successfully isolated and identified. Building on these findings, Sun et al. [

22] demonstrated that

B. pumilus and

B. clausii could be effectively incorporated into grouper diets as probiotics, leading to improved growth performance and enhanced health status. Shi et al. [

23] also explored the differences in gut microbiota of European eel,

A. anguilla and identified

Cetobacterium as the predominant genus in the intestinal microbiota of fast-growing individuals. This bacterial genus was suggested as a potential probiotic for European eels due to its association with enhanced growth performance. However, despite this promising observation, no follow-up studies have been conducted to validate the probiotic application of

Cetobacterium in European eel aquaculture. Further advancing this field, Zhang et al. [

12] investigated the gut microbiota of American eel,

A. rostrata and observed a higher relative abundance of Firmicutes, a phylum known for producing short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), in FG individuals compared to their SG counterparts. This finding suggests that the gut microbiota in FG eels is more efficient in fermenting non-digestible polysaccharides, thereby generating higher levels of SCFAs, which serve as critical energy sources for the host. Despite these promising results, Zhang et al. [

12] did not isolate specific bacterial strains from eel intestines to directly evaluate their probiotic potential. Collectively, these studies underscore the pivotal role of gut microbiota in modulating growth performance in aquaculture species. However, further research is needed to isolate and characterize candidate probiotic strains, assess their functional roles, and validate their efficacy in controlled aquaculture settings.

This study aims to comprehensively investigate the differences in gut microbiota between short-finned eels with varying growth rates. Specifically, it seeks to isolate and identify distinct bacterial strains with potential probiotic properties and assess their efficacy in promoting growth performance. Ultimately, this research aspires to mitigate growth rate disparities and size heterogeneity, addressing key challenges in eel aquaculture and contributing to more sustainable and efficient production practices.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Fish and Acclimation

Short-finned eels, A. bicolor pacifica, were obtained from a private eel farm in Pingtung, Taiwan. To investigate differences in gut microbiota between FG and SG eels, eels reared under identical conditions for 8 months in the same tank were immediately used for DNA extraction and probiotic isolation upon arrival at the laboratory. For the evaluation of probiotic efficacy on growth performance, juvenile eels (initial weight: 10.2 ± 0.5 g) were acclimated in a 4-ton tank (2 m × 2 m × 0.8 m; L × W × H) with a continuous water flow rate of 2.5 L min−1 for two weeks prior to the experiment. The water depth was maintained at 0.3 m, corresponding to an effective water volume of approximately 1.2 tons. During this acclimation period, the eels were fed a commercial dough diet twice daily at ~5% of their body weight.

2.2. Gut Microbiota Between FG and SG Eels

Eels weighing less than 100 g were classified as SG (3 fish), while those exceeding 500 g were classified as FG (3 fish). Before dissection, eels were anesthetized in ice water until they showed no movement. The intestines of SG (48.3 ± 8.5 g) and LG (633.5 ± 34.4 g) eels were carefully dissected on ice to preserve sample integrity. The intestinal tracts were meticulously emptied of luminal contents through gentle manual pressure, followed by three sequential rinses with sterile saline solution to ensure complete removal of residual material. A sterilized pair of fine surgical scissors was employed to excise the middle intestinal segment, which was subsequently placed on a sterile Petri dish. Remaining fecal residues were carefully extracted using sterile disposable pipettes and spoons to prevent cross-contamination. Intestinal mucus was then meticulously collected by scraping the inner surface of the intestinal tract with sterile instruments and immediately transferred into 1.5 mL tubes. To preserve sample integrity and prevent DNA degradation, the mucus samples were promptly processed for DNA extraction. A total of nine eels from each group were used in this analysis. For each biological replicate, mucus samples from three individual eels were pooled, resulting in three composite samples (three pools × three eels per pool). DNA extraction for each of the three pooled samples was performed using the DNeasy® PowerSoil® Pro Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, NRW, Germany) in strict accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol. DNA purity and concentration were evaluated using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (MN-193, Maestro Gen Inc., Hsinchu, Taiwan), with the 260/280 absorbance ratios ranging from 1.86 to 1.95 and the 260/230 ratios ranging from 2.07 to 2.17, indicating high purity and minimal contamination. Sample quality and integrity were further verified using the Agilent 4200 TapeStation system (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA), which yielded DNA Integrity Number (DIN) values of 9.2–9.6.

The full-length 16S rRNA gene was amplified from microbial genomic DNA extracted from samples using the universal primer pair 27F (AGRGTTYGATYMTGGCTCAG) and 1492R (RGYTACCTTGTTACGACTT), along with the KAPA HiFi HotStart Ready Mix PCR kit (KAPA Biosystems, Wilmington, MA, USA). The resulting PCR amplicons were evaluated for size distribution and concentration using the D5000 ScreenTape Assay on an Agilent TapeStation 4200 system (Agilent Technologies, USA). Subsequently, the pooled PCR products were purified with SMRTbell® cleanup beads (PacBio Biosciences, Menlo Park, CA, USA) and prepared into barcoded single-molecule real-time (SMRT) libraries using the SMRTbell® prep kit 3.0 (PacBio Biosciences, Menlo Park, CA, USA). The libraries underwent an additional purification step with SMRTbell® cleanup beads, followed by quantification using the Qubit 1X dsDNA High Sensitivity Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Mass, USA). Their size distribution was further verified with the D5000 ScreenTape Assay. Sequencing was performed on the PacBio Sequel IIe platform (PacBio Biosciences, Menlo Park, CA, USA), and the raw sequencing reads were processed into high-quality circular consensus sequences (CCS) using the CCS module within SMRT Link software version 25.3 (PacBio Biosciences, Menlo Park, CA, USA).

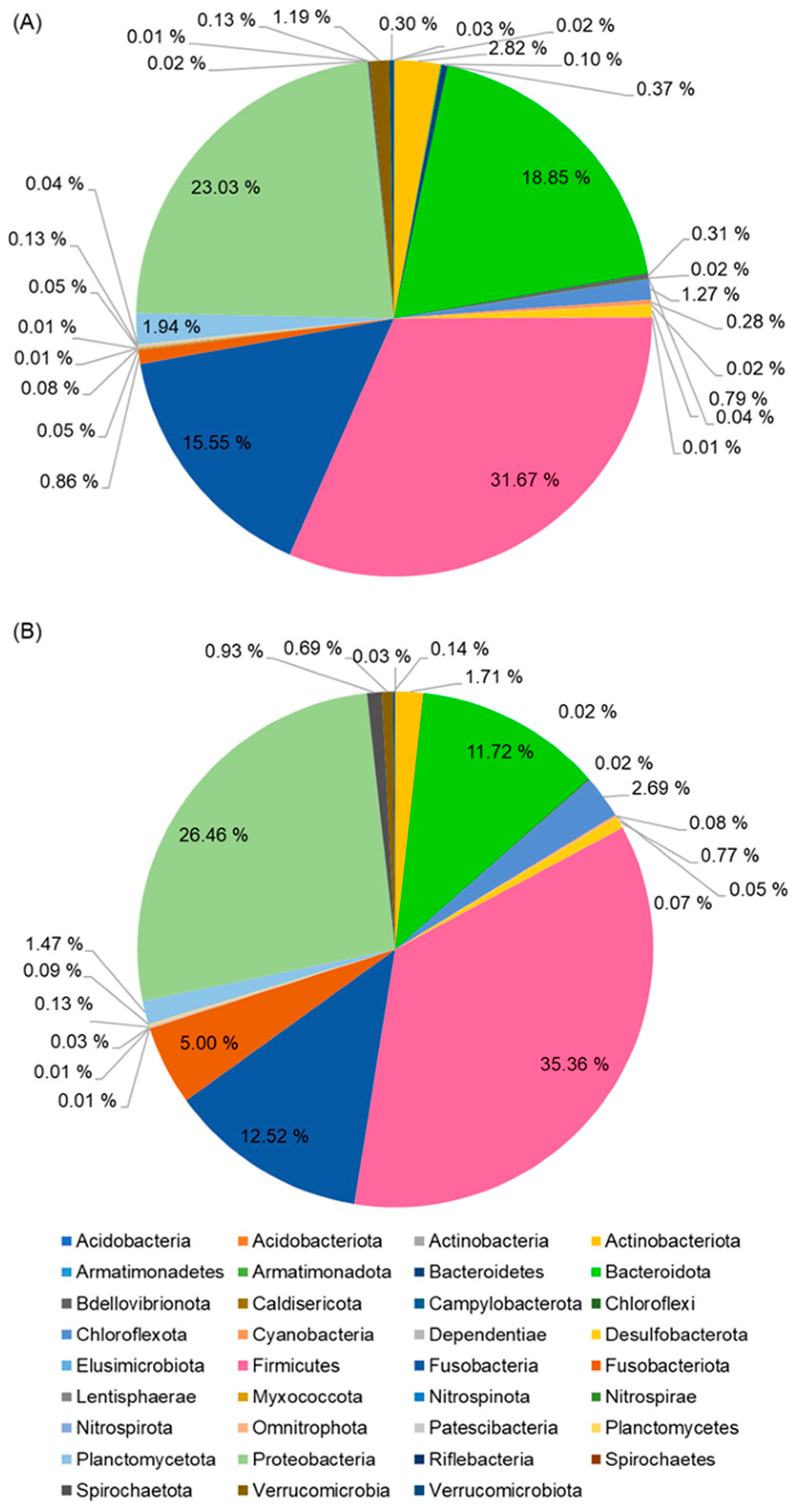

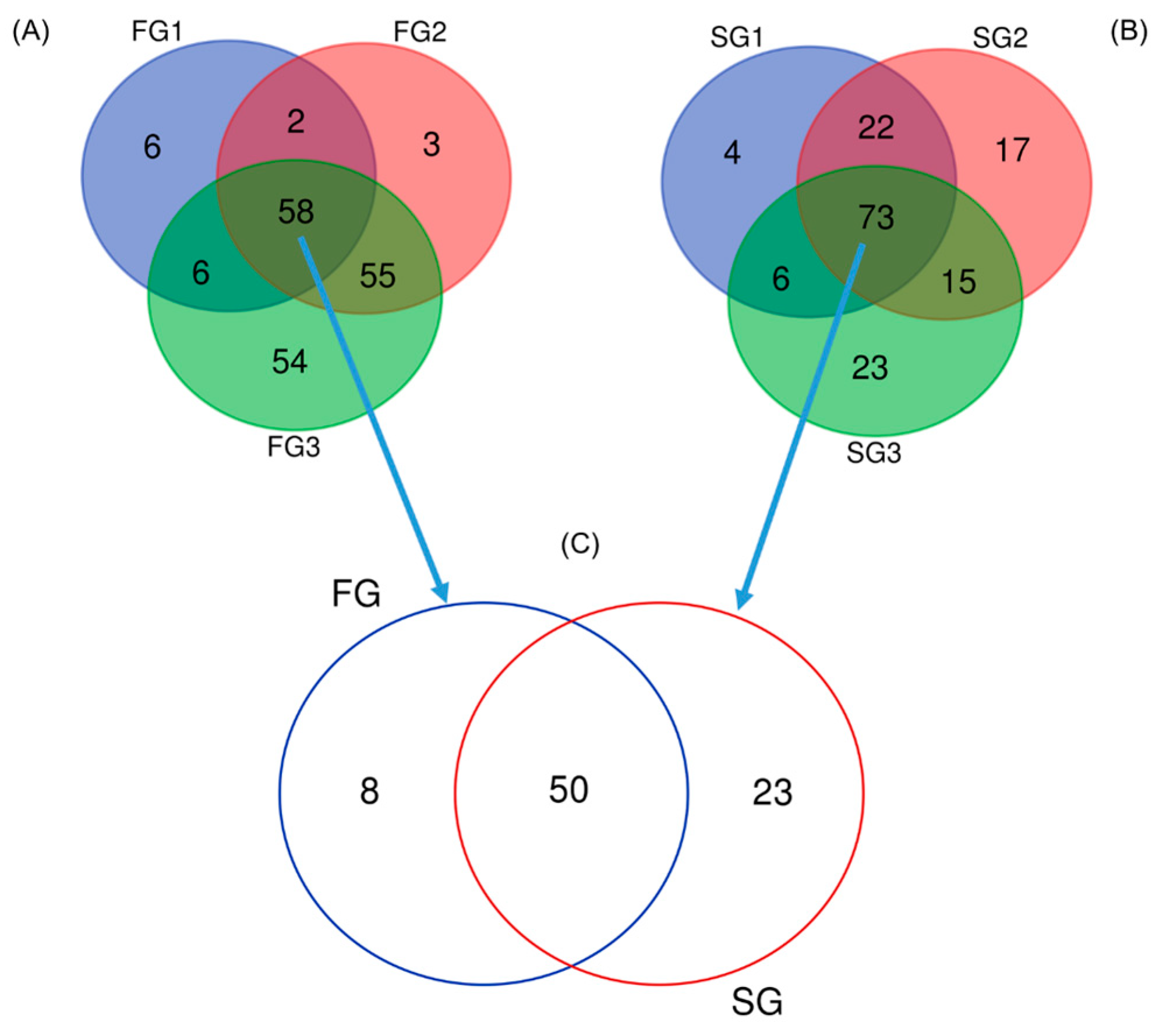

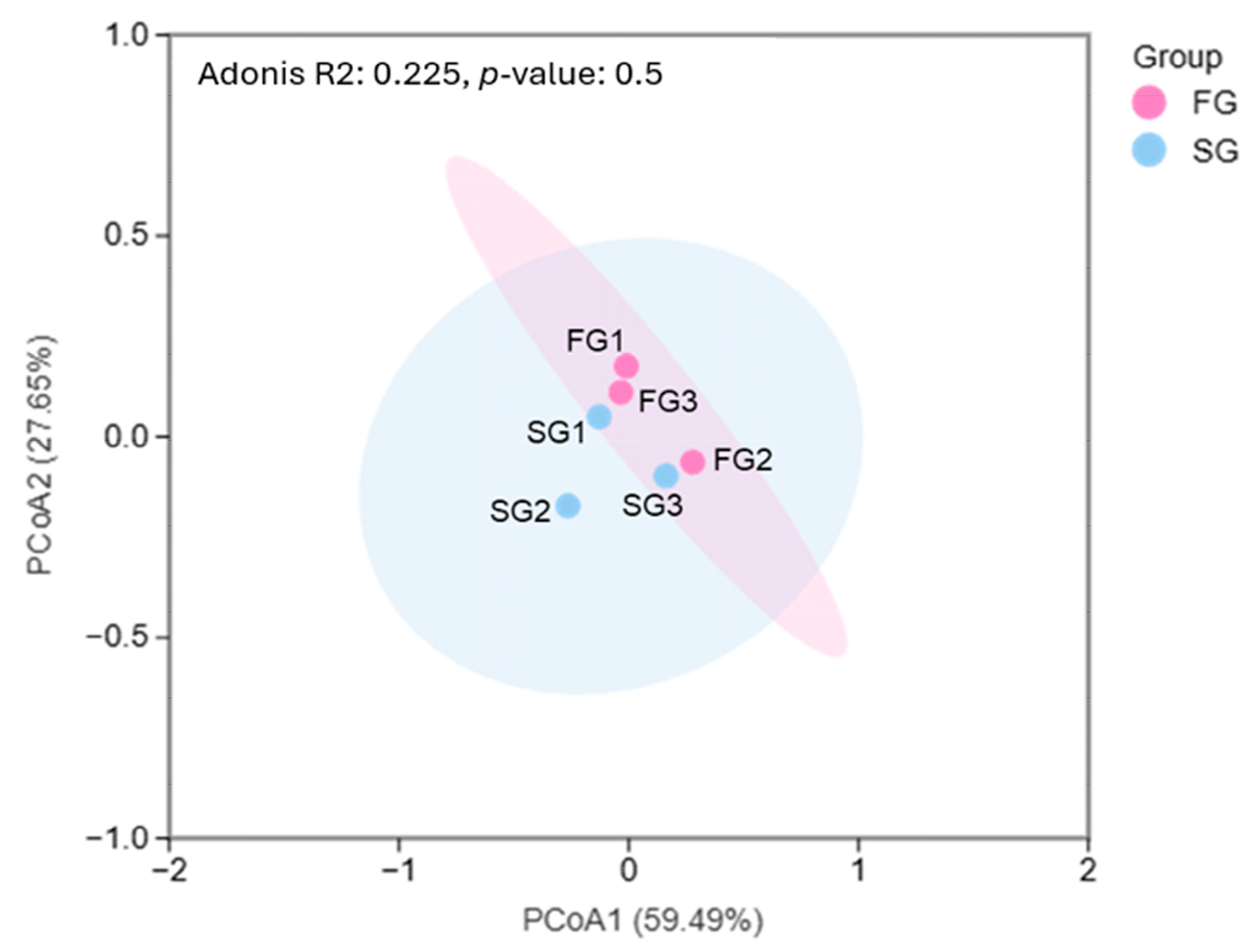

Taxonomic classification was achieved using the RDP Naive Bayesian Classifier algorithm [

24] with a minimum bootstrap confidence threshold of 50. The reference dataset included NCBI RefSeq records under BioProject 33175 and 33317 [

25], supplemented by the Ribosomal Database Project (RDP) [

26]. Prior to downstream analyses, low-abundance amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) were filtered out by removing ASVs with fewer than 20 total reads across all samples. This filtering step was implemented to eliminate potential sequencing artifacts and spurious rare variants that may compromise diversity estimation and ordination accuracy. Principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) was performed using the Bray–Curtis dissimilarity matrix on the Metware Cloud platform (Metware Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Wuhan, China). Key diversity indices, including Shannon’s diversity index, and Margalef’s species richness (d), were calculated using QIIME (

http://qiime.org/scripts/alpha_diversity.html (accessed on 8 December 2024)). Patterns of microbial dominance and cumulative species contributions were analyzed with the Plymouth Routines in Multivariate Ecological Research (PRIMER) software (Version 6.1.5).

2.3. Potential Probiotic Isolation from the Intestine of FG Eel

The intestinal mucus used for DNA extraction was also employed for the isolation of potential probiotics using nutrient agar (NA) (Difco TM Nutrient Agar, Spark, MD, USA). Briefly, the intestinal mucus was mixed with sterile saline solution (0.85% NaCl) and subsequently spread on NA following serial dilutions. The plates were then incubated at 27 °C for 4 days. Differences in colony morphology and colony count between FG and SG eels were observed. Distinct or abundant colonies were selected and transferred to fresh NA plates for further analysis.

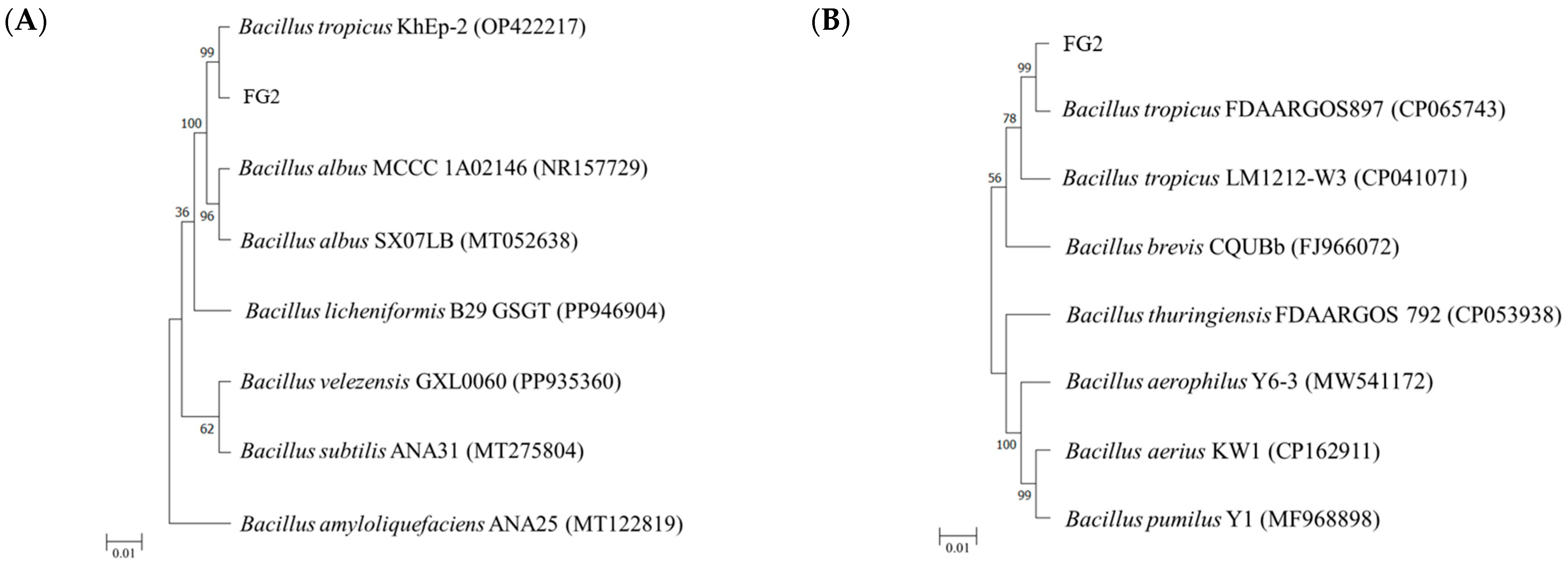

A total of 10 colonies (designated as FG1 to FG8 (isolated from FG eels), and SG9 to SG10 (isolates from SG eels)) exhibiting differences between FG and SG groups, were sent to Tri-Biotech, Inc. (Taipei, Taiwan) for species identification. Identification was performed using 16S rDNA and gyrase B (

gyrB) gene sequencing with the following primers: forward, 5′-GTGCCAGCAGCCGCGGTAA-3′, and reverse, 5′-GACTACCAGGGTATCTAATC-3′, and forward, 5′-ACATCGTGAAGGTAAAATCC-3′, and reverse, 5′-TCTCCGCCAATGTCGTACAT-3′, respectively. The obtained 16S rDNA and

gyrB sequences were compared against known sequences in the GenBank database using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) (NCBI Nucleotide BLAST,

https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi, accessed on 6 September 2024). Subsequently, a phylogenetic tree was constructed using Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.1 (available online:

http://www.megasoftware.net/, accessed on 6 September 2024). The tree was generated using the neighbor-joining method, with bootstrap values calculated from 1000 replicates. The tree was drawn to scale, with branch lengths proportional to evolutionary distances.

2.4. Selection of Probiotic Candidates Based on Digestive Enzyme Activity

Strains FG1~FG8 were selected for the analyzing digestive enzyme activity, while strains SG9 and SG10 were excluded from further investigation because their identification as potential pathogens, Aeromonas caviae and A. veronii, respectively. Initially, all selected strains underwent protease activity assessment. Strains exhibiting significantly higher protease activity were subsequently subjected to additional enzymetic assays to further characterize their digestive enzyme profiles. The strain exhibiting superior digestive enzyme activity was identified as a potential probiotic candidate and was subsequently evaluated for its probiotic efficacy in enhancing eel growth performance.

Prior to the assay of enzymatic activity, tested strains were inoculated in nutrient broth (NB) and incubated for 24 h at 150 rpm at 27 °C. Thereafter, bacteria were centrifuged for 20 min at 2840× g at 4 °C. The supernatant was transferred to a new tube and used for analysis of enzymatic activity.

2.4.1. Assessment of Enzymatic Activity

The protease activity assay was performed following the methodology described by Beg et al. [

27] with slight modifications. In brief, protease activity was measured in triplicate at 27 °C using a 100 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 9.0). Sample (100 μL) was incubated with 100 mL of a 1% (

w/

v) casein solution prepared in Tris-HCl buffer (pH 9.0) for 10 min at 27 °C. The enzymatic reaction was terminated by adding 500 mL of 5% (

v/

v) trichloroacetic acid (TCA). The mixture was then centrifuged at 3000×

g for 20 min, and the products were determined using a modified Lowry’s method. One unit of protease activity was defined as the amount of enzyme required to liberate 1 μg of tyrosine mL

−1 min

−1 under the specified assay conditions.

Lipase activity was assessed using the titrimetric method described by Teitz and Friedreck [

28], with minor modifications. Briefly, 1.5 mL of a stabilized olive oil emulsion, serving as the lipase substrate, was evenly mixed with 1.5 mL of 0.1 M Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0). Subsequently, 1 mL of sample was added to the mixture, followed by incubation at 27 °C for 6 h. The enzymatic reaction was terminated by adding 3 mL of 95% ethanol. Released free fatty acids were then titrated using 0.01 N NaOH with 0.9% (

w/

v) thymolphthalein in ethanol as an indicator. A blank control was prepared following the same protocol, except that the crude enzyme extract was added immediately prior to titration to account for background corrections. One unit of lipase activity was defined as the amount of 0.05 N NaOH required to neutralize the fatty acids liberated from the substrate during the incubation period, after correction for the blank.

Amylase activity was evaluated using the dinitrosalicylic acid (DNS) method, as described by Soy et al. [

29], with slight modifications. Briefly, 500 μL of sample was combined with 1 mL of 0.01 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.9) containing 0.5% soluble starch as the substrate. The reaction mixture was incubated at 25 °C for 10 min to allow enzymatic hydrolysis. After incubation, reducing sugars were quantified using the DNS reagent, and the absorbance of the resulting solution was measured spectrophotometrically at 540 nm. One unit of amylase activity was defined as the amount of enzyme required to liberate 1 μmol of maltose per min under the assay conditions (pH 6.9, 25 °C).

Cellulase activity was quantified by measuring the release of reducing sugars, expressed as glucose equivalents, using the DNS method, as described by Gascoigne and Gascoigne [

30], with slight modifications. Briefly, 45 μL of 1% carboxymethyl cellulose prepared in sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0) was combined with 10 μL of enzyme sample. The reaction mixture was incubated at 55 °C for 15 min to facilitate enzymatic hydrolysis. Upon completion of the incubation, 50 μL of DNS reagent was immediately added, and the mixture was then heated in a boiling water bath for 5 min to allow the formation of a chromogenic complex, followed by cooling to room temperature. The absorbance of the resulting solution was measured at 540 nm using a spectrophotometer (V-630, Jasco, Jasco Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). One unit of cellulase activity was defined as the amount of enzyme required to release 1 μmol of glucose per min under the specified assay conditions.

Xylanase activity performed following the method described by Bailey et al. [

31], with slight modifications. Briefly, the reaction mixture comprised 1.8 mL of a 1.0% (

w/

v) suspension of beechwood xylan prepared in 50 mM sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0) and 0.2 mL of enzyme sample in 50 mM sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0). The mixture was incubated at 60 °C for 5 min to facilitate enzymatic hydrolysis. Subsequently, 3 mL of DNS reagent was added to terminate the reaction and quantify the released reducing sugars. The mixture was then heated at 99 °C for 15 min, and the absorbance was measured spectrophotometrically at 540 nm. The concentration of reducing sugars was calculated using xylose as the standard. One unit of xylanase activity was defined as the amount of enzyme required to release 1 μmol of reducing sugar, expressed as xylose equivalents, per min under the assay conditions.

Phytase activity was assessed by mixing 500 µL of the sample with 250 µL of 0.2 M sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.15) and 5 mM sodium phytate. The reaction mixtures were incubated at 27 °C in a water bath for 45 min to facilitate enzymatic activity. To terminate the reaction, 1 mL of 15% (

w/

v) TCA was promptly added. Subsequently, 500 µL of the reaction mixture was mixed with 4 mL of freshly prepared colorimetric reagent, consisting of acetone, 10 mM ammonium molybdate, and 5 N sulfuric acid in a 2:1:1 (

v:

v:

v) ratio, along with 400 µL of 1 M citric acid. The released inorganic phosphate was quantified spectrophotometrically at a wavelength of 355 nm. A standard curve was constructed using potassium dihydrogen phosphate (KH

2PO

4) as a standard, following the methodology described by Heinonen and Lahti [

32]. One unit of phytase activity was defined as the amount of enzyme required to liberate 1 µmol of inorganic phosphate per min from a 5 mM sodium phytate solution under the assay conditions.

Specific activity for all determined enzyme was expressed as U mg−1 of protein, and protein concentration in the sample was determined using a Bio-Rad protein assay kit (no. 500-0006, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Berkeley, CA, USA) with bovine serum albumin (Sigma, Louis, MO, USA) as a standard.

2.4.2. Virulence Assessment for Aquatic Animals

Several aquatic species, including 3 fish and 3 crustacean species (

Table 1), were used to assess the virulence of the selected strain FG2 through injection. Test animals were procured from private aquaculture farms, transferred to the aquafarm facility at NPUST, Taiwan, and acclimated for seven days. During the acclimation period, fish and crustacean were fed a commercial diet twice daily.

The assessment was performed in aquaria containing 20 L of water, with each species evaluated in triplicate, and each replicate consisting of 10 animals. Virulence assessment was conducted via injection at a dose of 109 cfu (g weight)−1 over a 14-day period. Throughout the experiment, water quality was maintained by daily water renewal. Mortality rates were monitored twice daily, at 9:00 a.m. and 4:00 p.m. Water temperature was maintained at 28 °C using submersible heaters, while dissolved oxygen (DO) levels were kept at ≥5 mg L−1 through continuous aeration.

2.5. Assessment of Probiotic Efficiency

To evaluate whether the isolated strain FG2 could enhance the growth performance of eels, the bacterium was incorporated into the diet at a level of 109 cfu (kg diet)−1, and a 56-day feeding trial was subsequently conducted.

2.5.1. Probiotic Preparation

The selected strains FG2 was inoculated in NA and incubated for 24 h at 27 °C, one colony was then transferred to NB and incubated for 24 h at 150 rpm at 27 °C. Thereafter, bacteria were centrifuged for 20 min at 2840× g at 4 °C. The supernatant was discarded and the pellet was washed twice with sterile 0.9% NaCl. The pellets were dissolved in 10% skim milk and freeze-dried (Freeze dryer 5030/8530, Pannchum, Kaohsiung, Taiwan). The probiotic powder was stored at −20 °C until use. The viability of bacteria was determined by the spread plating on NA.

2.5.2. Experimental Diet Preparation

The composition of the experimental diets is presented in

Table 2. The protein and lipid contents were formulated to approximate 48% and 10%, respectively, ensuring optimal nutritional balance for the target species. Initially, all feed ingredients were finely ground into powder, sieved through a #60-mesh screen, and homogeneously mixed with fish oil to achieve uniform distribution. The resulting feed mixture was subsequently stored at 4 °C to preserve its integrity until use. Prior to feeding trials, the proximate composition of the diets was analyzed following the standard protocols outlined by the Association of Official Analytical Chemists [

33]. Crude protein was determined using the Kjeldahl method with a Kjeltec System (Tecator, Höganäs, Sweden). Crude lipid was measured using the Soxhlet extraction method. Moisture content was analyzed using a moisture analyzer (MX-50, A&D Company, Tokyo, Japan). Ash content was determined by incineration in a muffle furnace at 550 °C. Furthermore, the concentration of probiotics in the diets was quantified using the spread plate method, with bacterial colonies identified. The concentration of

Bacillus spp. in the control and experimental diets was determined to be 1 × 10

2 cfu (kg diet)

−1 and 1.2 × 10

9 cfu (kg diet)

−1, respectively, ensuring precise bacterial supplementation in accordance with experimental design criteria.

2.5.3. Fish Rearing

The growth performance trial was conducted in indoor cement tanks with dimensions of 2 m × 2 m × 0.8 m, filled with water to a depth of 0.3 m. Aeration was continuously supplied via air stones, and water flow was maintained at a rate of 0.5 L min−1 to ensure DO levels remained above 5 mg L−1 and to uphold optimal water quality throughout the experimental period.

Two experimental groups were conducted: a control group without probiotic supplementation and a treatment group supplemented with probiotics at a concentration of 10

9 cfu (g diet)

−1. Each group was conducted in triplicate, with 100 juvenile eels allocated per replicate tank. The growth trial was performed for 56 days, during which fish were fed a feed dough prepared by mixing the powdered diet with water at a ratio of 1:1.2 (

w/

w) to form a cohesive dough. Feeding was performed twice daily at a feeding rate equivalent to 5% of the body weight. After 2 h of feeding, uneaten feed was carefully collected and dried in an oven at 100 °C. The total feed intake was then calculated by subtracting the weight of the uneaten feed from the total feed provided. Throughout the experiment, 10 fish from each tank were randomly sampled and weighed biweekly to adjust the feeding rate according to their updated body weight. At the end of the feeding trial, individual fish weight and body length were meticulously measured, and growth performance parameters were calculated as follows:

2.5.4. Body Composition

Following last weight and length measurements, 6 eels from each group were euthanized by immersion in ice water. The dorsal muscle tissue was carefully dissected, dried in a hot air oven at 70 °C for 24 h, and subsequently stored in a refrigerator for further chemical analysis. Proximate composition, including crude protein, crude lipid, dry matter, and ash content, was determined according to the standard methods outlined by the Association of Official Analytical Chemists [

33].

2.6. Statistical Analysis

A Completely Randomized Design was used in this study, and juvenile eels were randomly allocated to the experimental tanks corresponding to each dietary treatment. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Prior to conducting ANOVA, Levene’s test and the Shapiro–Wilk test were applied to assess homogeneity of variances and normality, respectively. Probiotic enzyme activities were analyzed using one-way ANOVA to evaluate differences among treatments. When significant effects were detected, Tukey’s HSD post hoc test was used to determine pairwise differences among groups. Independent-samples t-tests were used to compare the relative abundance and alpha-diversity indices of gut microbiota between the FG and SG groups, as well as growth performance and the proximate composition of dorsal muscle between the control and probiotic treatment groups. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

4. Discussion

The intestinal microbiota comprises a diverse and dynamic community of microorganisms that inhabit the gastrointestinal tract of the host. These microorganisms play an essential role in a wide array of biochemical processes, including nutrient digestion and absorption, metabolic regulation, and the modulation of host growth and development [

12,

34,

35]. Furthermore, the intestinal microbiota is critical for the development and regulation of the host’s immune system, acting as a pivotal mediator of immune responses and contributing to the maintenance of homeostasis [

36]. It has been well-documented that the composition of the gut microbiota is influenced by factors such as host age, nutritional status, and environmental conditions [

35,

37,

38].

In recent years, increasing attention has been directed toward understanding the gut microbiota as a key intrinsic factor in host health and growth. The microbial community not only contributes to nutrient metabolism but also plays a vital role in supporting host growth and mitigating disease risks [

19,

25,

36]. For instance, Sun et al. [

21] demonstrated that differences in the gut microbiota were evident between slow-growing and fast-growing groupers,

E. coioides. In their study, four

Vibrio species were isolated from the gut of slow-growing groupers, whereas only two

Vibrio species were detected in fast-growing groupers. Additionally, potential probiotic species such as

B. pumilus,

B. clausii, and

Psychrobacter sp. were found to dominate the gut microbiota of fast-growing groupers. Similarly, variations in gut microbial composition have been observed in eels with different growth rates. In European eels, Fusobacteria were the dominant phylum in fast-growing individuals, while Spirochaetes prevailed in slow-growing counterparts. Furthermore, the relative abundances of

Plesiomonas,

Turicibacter,

Nitrospira, and

Lachnospiraceae bacterium NK4A136 were positively correlated with growth rates [

22]. In swamp eels,

Monopterus albus, notable differences in bacterial composition were also recorded between small and large individuals. Burkholderiales were significantly more abundant in swamp eels, whereas Clostridiales exhibited higher proportions in larger ones. Additionally, almost all Fusobacteria detected in the gut of larger eels belonged to the genus

Cetobacterium [

39]. In American eels, notable shifts in the relative abundances of bacterial phyla were observed between slow-growing and fast-growing individuals. Slow-growing eels exhibited higher relative abundances of Proteobacteria (74.17%) compared to fast-growing eels (59.08%), whereas Firmicutes and Bacteroidota were enriched in fast-growing eels. At the genus level, potential pathogenic bacteria, including

Pseudomonas and

Mycoplasma, were predominant in slow-growing eels. In contrast, several genera within the Firmicutes phylum (

Coprococcus,

Dialister,

Clostridium,

Dorea, and

Blautia) and the genus

Larkinella within the Bacteroidota phylum were significantly enriched in fast-growing eels [

12]. Many of these genera, identified in fast-growing American eels, are considered potential probiotics [

40,

41]. In the present study, similar patterns of microbial variation were observed between fast-growing and slow-growing short-finned eels. The dominant phyla included Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, Bacteroidota, and Fusobacteria. Consistent with findings in American eels [

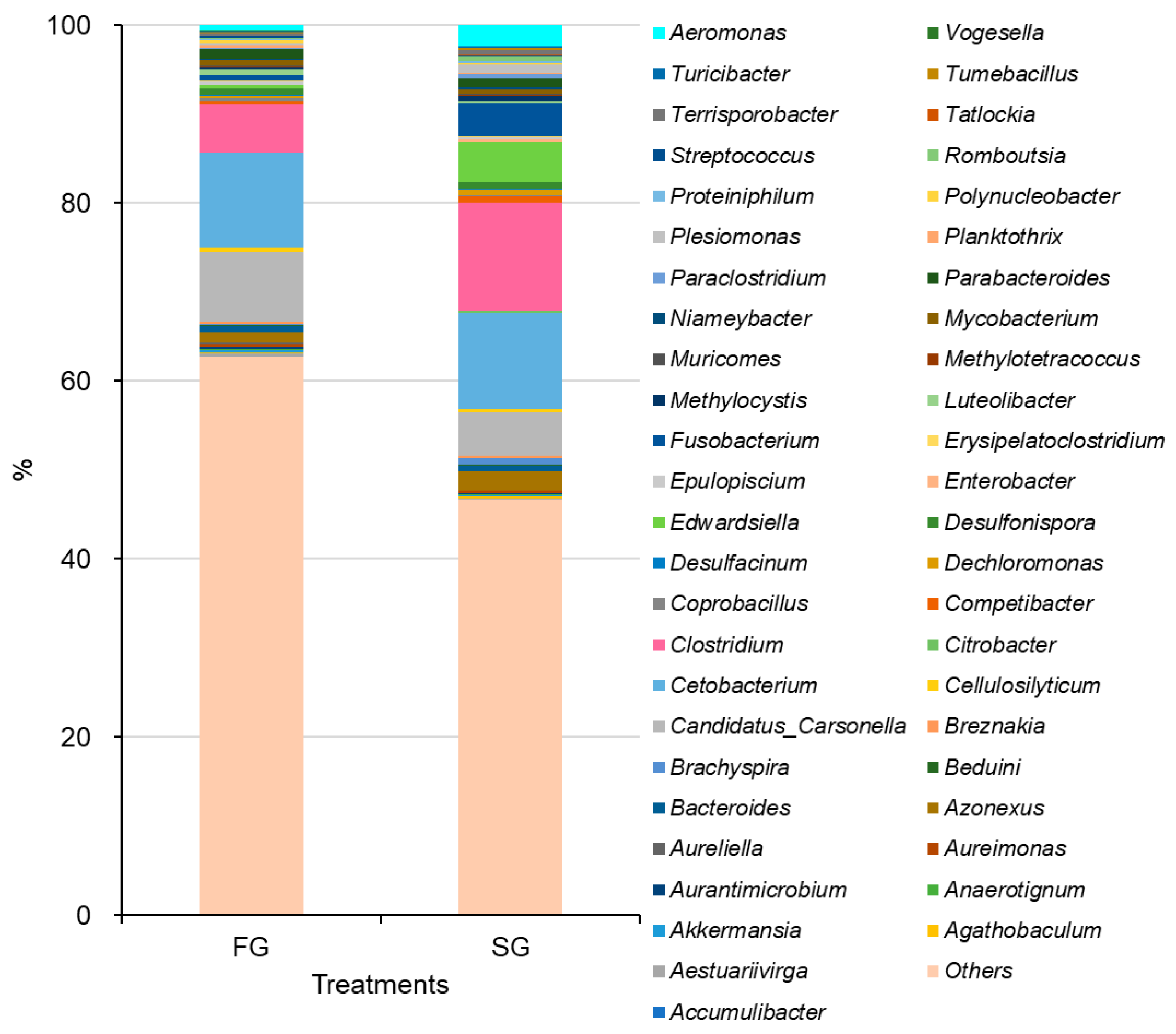

12], fast-growing short-finned eels exhibited higher relative abundances of Firmicutes and Bacteroidota, while Proteobacteria were more abundant in slow-growing individuals. At the species level, potential pathogenic bacteria such as

E. tarda and

A. jandaei were more prevalent in slow-growing eels, whereas the probiotic bacterium

B. tropicus was enriched in fast-growing eels. The higher abundance of beneficial bacteria in fast-growing eels, coupled with the reduced presence of pathogenic bacteria, likely contributes to enhanced growth performance and a lower risk of disease, as observed in both the current study and prior research on American eels [

12].

The relative abundance of bacteria, including

E. tarda and

A. jandae, identified in slow-growing eels, has been recognized as significant pathogens in aquaculture fish [

42,

43]. Among them,

E. tarda is a primary etiological agent of Edwardsiellosis, a severe systemic bacterial disease that affects various fish species, including eels [

42,

44]. Alcaide et al. [

44] reported the isolation of

E. tarda from body ulcers and internal organs of wild European eels in a Mediterranean freshwater coastal lagoon. All isolates of

E. tarda demonstrated virulence in eels, with lethal dose 50% (LD50) values ranging from 10

4.85 to 10

6.83 cfu per individual, confirming their role as the causative agents of the hemorrhagic disease observed in wild European eels. Edwardsiellosis caused by

E. tarda has also been diagnosed in farmed

A. marmorata, leading to high mortality rates. Affected eels exhibited severe hemorrhages in multiple organs, increased melano-macrophage activity in the spleen and kidney, and cytoplasmic vacuolation along with liquefactive necrosis in the brain [

45]. Similarly, outbreaks of Edwardsiellosis caused by

E. tarda have been reported in farmed

A. japonica, resulting in substantial mortality [

42]. Therefore, the higher abundance of

E. tarda observed in the intestines of slow-growing eels suggests that these eels are not only characterized by reduced growth rates but are also at an elevated risk of developing Edwardsiellosis, particularly under suboptimal culture conditions.

In addition to

E. tarda,

Aeromonas has been identified as another significant pathogen affecting cultured eels. For instance,

A. hydrophila, a common bacterium in freshwater fish, has been demonstrated to be a fully pathogenic agent in eels [

46]. This Gram-negative pathogen, characterized by its short rod-shaped morphology, motility, fermentative metabolism, and β-hemolytic activity, was isolated from diseased short-finned eels exhibiting abnormal behavior and experiencing high mortality rates [

47]. Both

A. hydrophila and

A. jandaei have been confirmed as pathogenic bacteria in European eels, with O-serotypes serving as critical epidemiological markers for motile

Aeromonas strains pathogenic to eels [

48].

A. jandaei is a mesophilic species typically associated with opportunistic infections in fish [

48,

49]. Strains of

A. jandaei have frequently been isolated from cultured eels suffering from “red fin disease” [

50,

51]. In this study,

A. jandaei was found to be relatively more abundant in the gut of slow-growing eels compared to fast-growing eels. This observation suggests that slow-growing eels may be more susceptible to developing red fin disease, particularly under deteriorating environmental conditions.

B. tropicus is a Gram-positive, rod-shaped bacterium characterized by parallel-sided cells with predominantly bluntly rounded ends, though truncation may occasionally be observed. This microorganism exhibits morphological plasticity, appearing as single cells, pairs, unjointed filaments, and both short and long chains. Sporulation occurs rapidly on solid media, typically within 24 h; however, in liquid media, spore formation is comparatively delayed. Notably, spores are not detected in vivo during the organism’s lifecycle.

B. tropicus is motile, possessing robust peritrichous flagella. Its colony morphology closely resembles that of

B. anthracis [

52], albeit with less pronounced curling at the colony margins. In certain cases, the colonies exhibit a perforated appearance, whereas in its shorter form, they appear granular with irregular borders [

52]. Functionally,

B. tropicus is recognized as a beneficial bacterium, particularly due to its production of keratinase, an enzyme capable of degrading poultry feathers [

53]. Additionally,

B. tropicus has been isolated from the intestinal tract of tilapia and identified as a potential probiotic, given its antagonistic activity against multiple aquaculture pathogens, including

Staphylococcus aureus,

Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and

S. pyogenes [

53]. In the present study, the relatively higher abundance of

B. tropicus in fast-growing eels may be linked to a concomitant reduction in the abundance of pathogenic bacteria within the intestinal microbiota, suggesting a potential role in promoting host health.

In this study,

B. tropicus FG2, a strain associated with rapid growth, was successfully isolated from the intestines of fast-growing eels. This strain was selected based on its robust production of digestion-related enzymes, including protease, lipase, amylase, xylanase, cellulase, and phytase. The exceptional enzymatic profile of

B. tropicus FG2 highlights its potential as a probiotic candidate in aquaculture systems. A primary benefit of probiotics in aquaculture is their ability to enhance nutrient utilization in host. This is achieved through the production of supplemental digestive enzymes and the degradation of anti-nutritional factors in feed. Probiotic-derived enzymes maintain functionality as the probiotics pass through the host’s gastrointestinal tract, eventually colonizing and proliferating in the intestines. Proteases, for instance, catalyze the hydrolysis of proteins into peptides and free amino acids, which are readily absorbed by intestinal epithelial cells. Numerous studies have demonstrated the growth-promoting effects of protease-producing probiotics in aquaculture species, such as white shrimp,

P. vannamei [

54] (Liu et al., 2009) and parrotfish,

Oplegnathus fasciatus [

55]. In addition to protease,

B. tropicus FG2 exhibits the ability to produce amylase, cellulase, and xylanase. These enzymes are essential for the digestion of carbohydrates, such as starch, cellulose, and hemicellulose, which are abundant in aquafeeds. For example,

B. safensis NPUST1, another probiotic strain capable of producing these enzymes, was incorporated into the diet of Nile tilapia,

Oreochromis niloticus, resulting in significant improvements in growth performance and feed efficiency [

56]. Phytic acid, a common anti-nutrient found in plant-based feed ingredients, chelates essential minerals such as iron, zinc, calcium, and phosphate, thereby reducing their bioavailability in the host’s intestines [

57]. The enzyme phytase hydrolyzes phytic acid, liberating these bound minerals and improving their absorption. This has been demonstrated in

B. subtilis E20, whose phytase activity effectively degrades phytic acid, leading to enhanced nutrient utilization and growth in aquatic animals [

58]. Given the enzymatic capabilities of

B. tropicus FG2, including its production of protease, lipase, amylase, cellulase, xylanase, and phytase, it is reasonable to infer that this strain contributes to the digestion and absorption of proteins, lipids, carbohydrates, and minerals in aquaculture species. These mechanisms likely underlie the observed improvements in feed efficiency and growth performance, thereby highlighting the potential of

B. tropicus FG2 as a probiotic for application in aquaculture.

Bacillus species have been extensively utilized as probiotics to enhance the growth performance and health of aquaculture species [

59].

Bacillus is a Gram-positive, rod-shaped, spore-forming bacterium that is either aerobic or facultatively anaerobic, allowing it to thrive in diverse environments. These bacteria can be isolated from various sources, including soil, air, water, animal intestines, vegetables, and fermented foods [

60,

61]. This ecological versatility underscores their adaptability and potential as probiotics in aquaculture systems. Despite their benefits, certain

Bacillus species have been identified as opportunistic pathogens or producers of toxins that can pose risks to host animals. Therefore, it is essential to evaluate the safety of specific

Bacillus strains before their application as probiotics [

54]. In the present study, the safety of

B. tropicus FG2 was rigorously assessed for its application in aquaculture. This evaluation involved high-dose (10

9 cfu per gram of body weight) injections in six aquatic species, including 3 fish species and 3 crustaceans. No mortalities were observed in any of the tested animals, indicating that

B. tropicus FG2 does not exhibit acute pathogenicity or toxicity under the conditions tested. These findings suggest that

B. tropicus FG2 is a safe candidate for use as a probiotic in aquaculture.

Beyond safety,

B. tropicus FG2 has shown the potential to enhance the growth performance of short-finned eels when incorporated into their diet at a concentration of 10

9 cfu per kg of feed. A subsequent investigation, consistent with the present study, also demonstrated that dietary supplementation with

B. tropicus FG2 significantly enhanced the growth performance of short-finned eels [

62]. The observed improvement in growth performance may be attributed to the digestive enzymes produced by the probiotic, which enhance nutrient utilization. In addition to its impact on growth performance, dietary supplementation with

B. tropicus FG2 resulted in an increase in lipid content in the dorsal muscle of short-finned eels. This effect may be associated with the higher lipase activity of

B. tropicus FG2, which likely enhances lipid digestion and absorption, leading to greater lipid deposition in muscle tissues.

Although the current findings highlight the dual benefits of B. tropicus FG2 in promoting both growth and nutritional composition, certain limitations should be acknowledged. In this study, the intestinal microbiota composition of eels was not analyzed following probiotic feeding, and the persistence or colonization capacity of B. tropicus FG2 in the gut was not directly determined. Given that B. tropicus FG2 was originally isolated from the eel intestine, its potential for colonization is plausible; however, direct evidence remains lacking. Future studies should therefore integrate high-resolution microbiome profiling (e.g., 16S rRNA sequencing, metagenomics) and strain-specific tracking approaches (e.g., qPCR, genome-based markers) to elucidate how B. tropicus FG2 modulates gut microbial ecology and contributes to digestive physiology and host health. Such mechanistic insights, together with long-term assessment and on-farm validation under commercial rearing conditions, are essential to fully establish the applicability and functional stability of B. tropicus FG2 as a next-generation probiotic for aquaculture.