Segment-Specific Functional Responses of Swine Intestine to Time-Restricted Feeding Regime

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

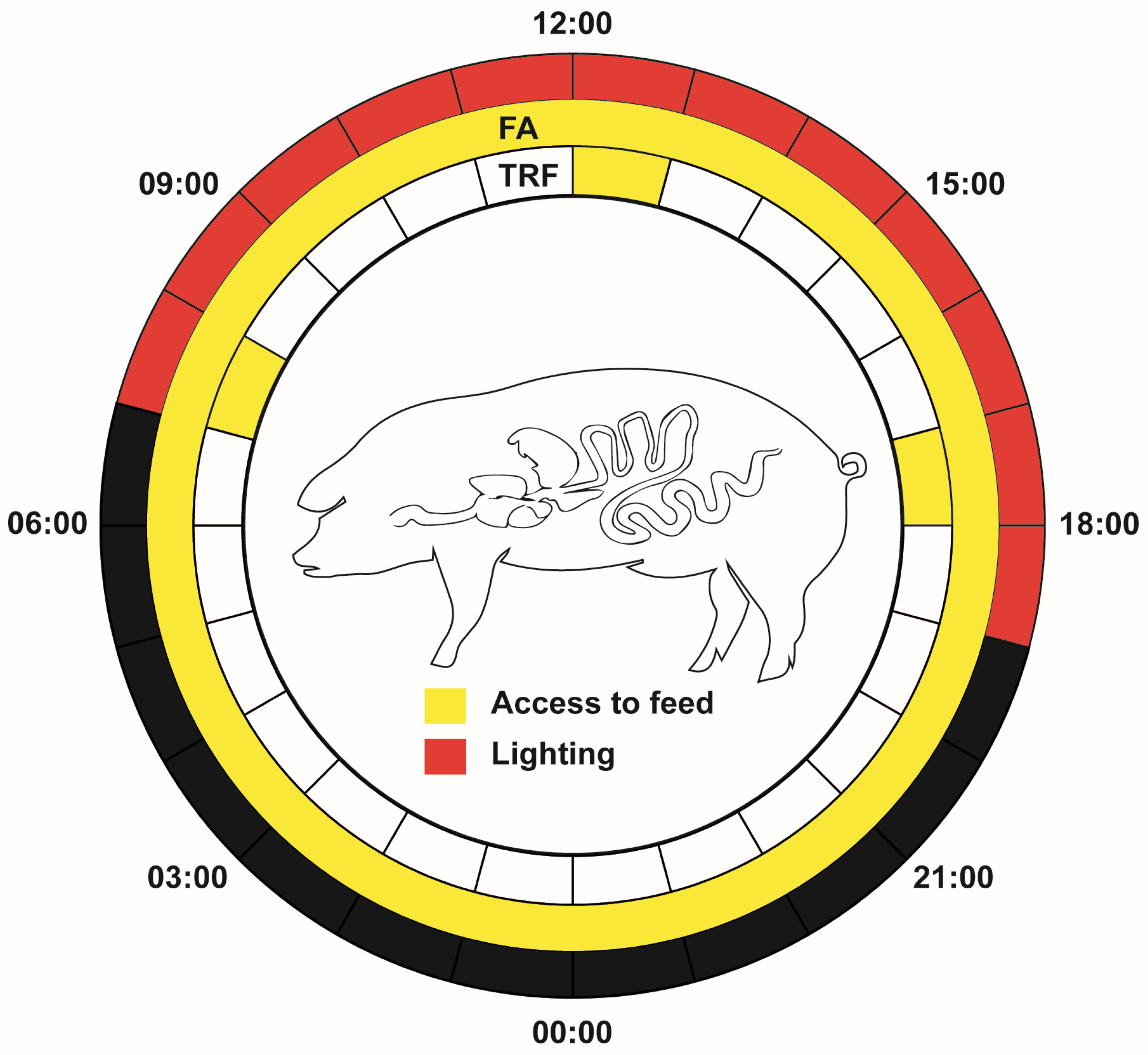

2.2. Animals, Housing, and Sampling

2.3. Tissue Indices of Jejunum and Colon

2.4. Apparent Total Tract Digestibility

2.5. Digestive Enzyme Activities

2.6. Colonic Nutrient Substrates

2.7. Total RNA Extraction and Transcriptome Analyses

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Effects of TRF on the Length and Tissue Indices of Jejunum and the Colon of Pigs

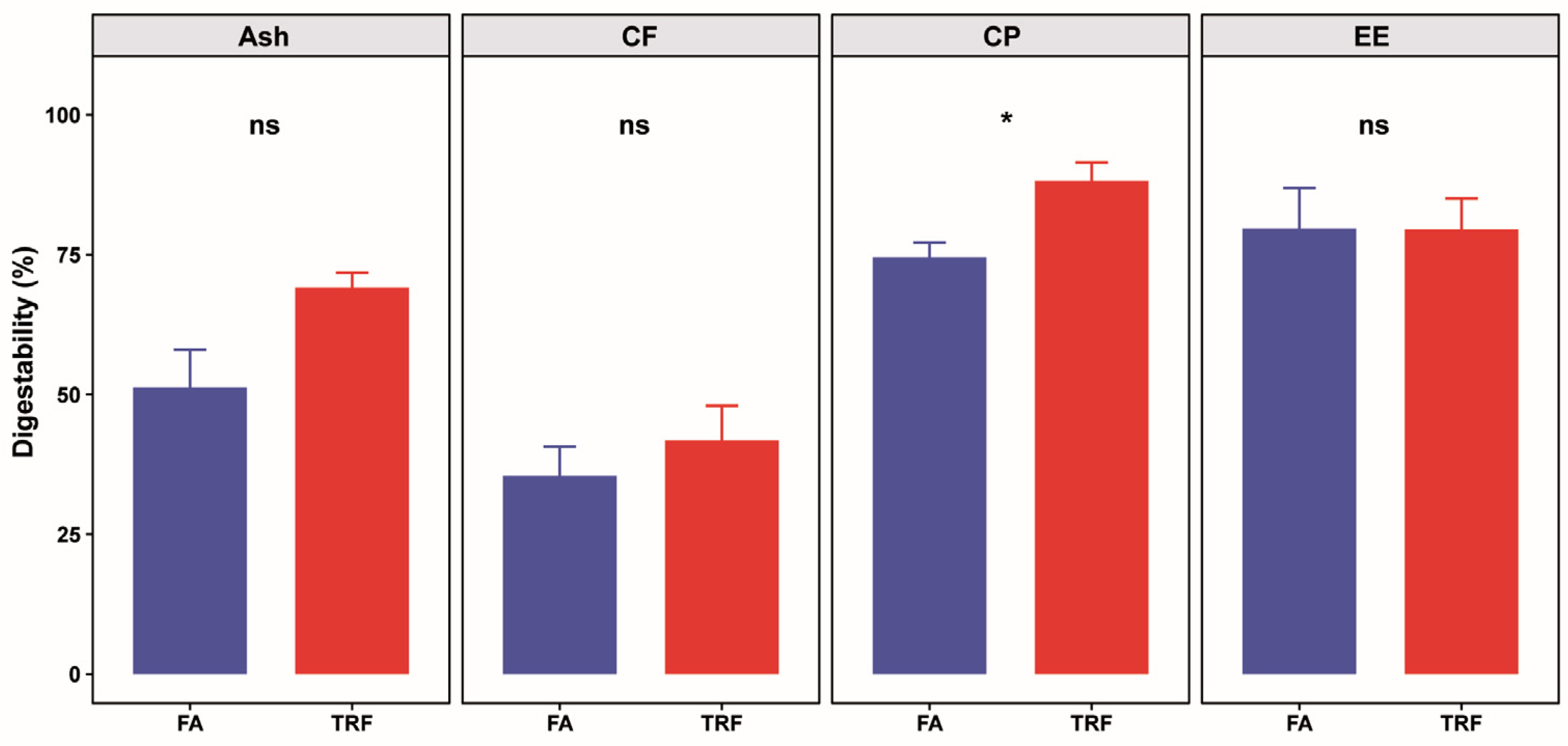

3.2. Effects of TRF on Apparent Total Tract Digestibility of Approximate Nutrients

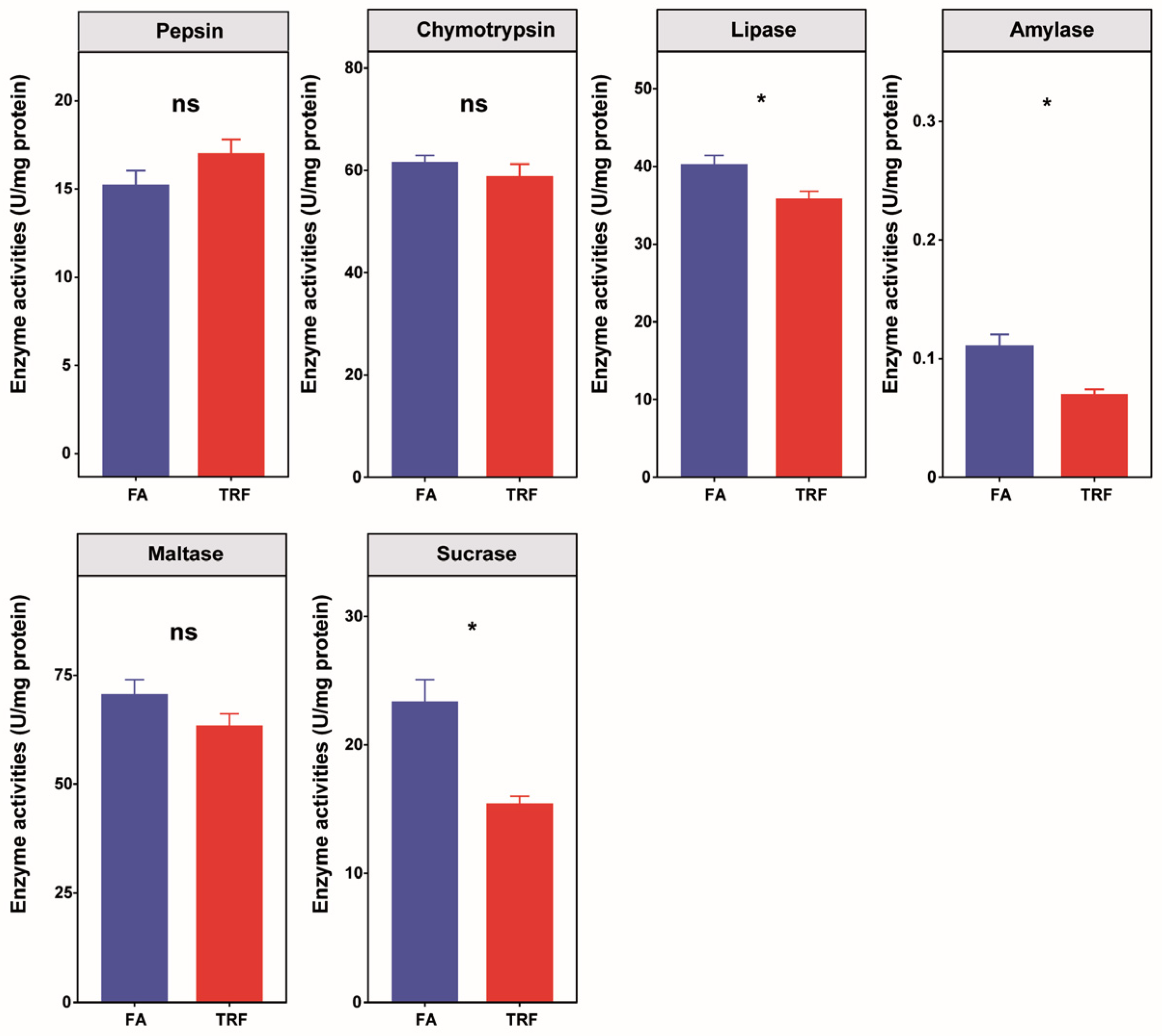

3.3. Effects of TRF on Digestive Enzyme Activities in the Gastro-Intestine of Pigs

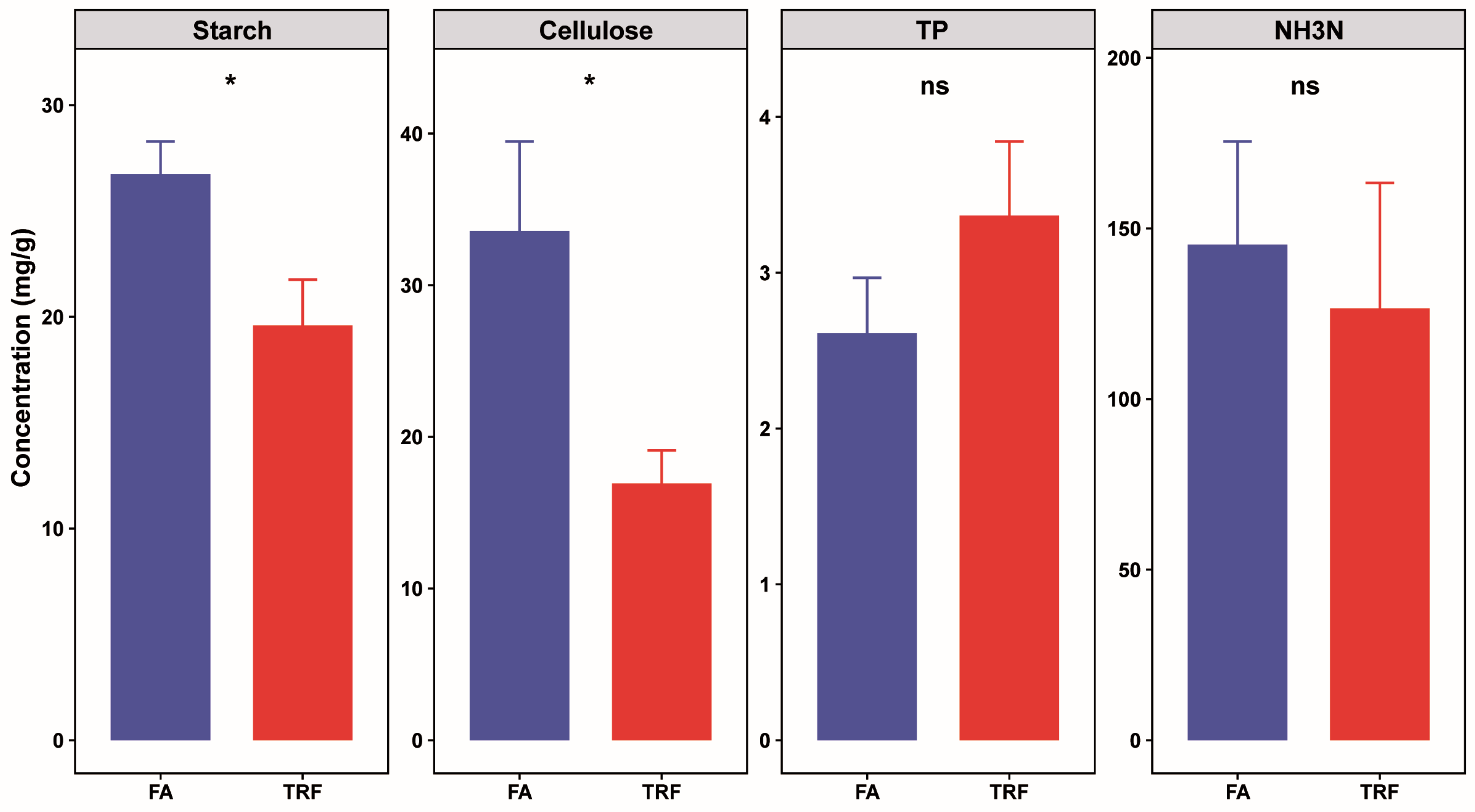

3.4. Effects of TRF on Colonic Nutrient Substrates of Pigs

3.5. Jejunal Transcriptomic Responses of Growing Pigs Under Different Feeding Patterns

3.6. Colonic Transcriptomic Responses of Growing Pigs Under Different Feeding Patterns

3.7. Comparative Transcriptomic Profiles Between Jejunum and the Colon of Growing Pigs Under Different Feeding Patterns

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Ash | Crude ash |

| ATTD | Apparent total tract digestibility |

| CF | Crude fiber |

| CP | Crude protein |

| DEGs | Differentially expressed genes |

| EE | Ether extract |

| FA | Ad libitum feeding |

| GO | Gene ontology |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| TRF | Time-restricted feeding |

References

- Xia, P.K.; Wang, H.Y.; Zhang, H.; Su, Y.; Zhu, W.Y. Effects of time-restricted feeding on the growth performance and liver metabolism of pigs. Acta Vet. Zootech. Sin. 2022, 53, 2228–2238. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Xia, P.; Lu, Z.; Su, Y.; Zhu, W. Time-restricted feeding affects transcriptomic profiling of hypothalamus in pigs through regulating aromatic amino acids metabolism. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2023, 103, 1578–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaix, A.; Zarrinpar, A.; Miu, P.; Panda, S. Time-restricted feeding is a preventative and therapeutic intervention against diverse nutritional challenges. Cell Metab. 2014, 20, 991–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, H.A.; Zibellini, J.; Harris, R.A.; Seimon, R.V.; Sainsbury, A. Effect of Ramadan Fasting on Weight and Body Composition in Healthy Non-Athlete Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2019, 11, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Barha, N.S.; Aljaloud, K.S. The Effect of Ramadan Fasting on Body Composition and Metabolic Syndrome in Apparently Healthy Men. Am. J. Men’s Health 2019, 13, 1557988318816925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feillet, C.A.; Albrecht, U.; Challet, E. “Feeding time” for the brain: A matter of clocks. J. Physiol.-Paris 2006, 100, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokkan, K.A.; Yamazaki, S.; Tei, H.; Sakaki, Y.; Menaker, M. Entrainment of the circadian clock in the liver by feeding. Science 2001, 291, 490–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damiola, F.; Le Minh, N.; Preitner, N.; Kornmann, B.; Fleury-Olela, F.; Schibler, U. Restricted feeding uncouples circadian oscillators in peripheral tissues from the central pacemaker in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Genes Dev. 2000, 14, 2950–2961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, J.; Gupta, A.; Osadchiy, V.; Mayer, E.A. Brain–gut–microbiome interactions and intermittent fasting in obesity. Nutrients 2021, 13, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeb, F.; Osaili, T.; Obaid, R.S.; Naja, F.; Radwan, H.; Cheikh Ismail, L.; Hasan, H.; Hashim, M.; Alam, I.; Sehar, B. Gut microbiota and time-restricted feeding/eating: A targeted biomarker and approach in precision nutrition. Nutrients 2023, 15, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeb, F.; Wu, X.; Chen, L.; Fatima, S.; Chen, A.; Xu, C.; Jianglei, R.; Feng, Q.; Li, M. Time-restricted feeding is associated with changes in human gut microbiota related to nutrient intake. Nutrition 2020, 78, 110797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xu, R.; Li, Q.; Su, Y.; Zhu, W. Daily fluctuation of colonic microbiome in response to nutrient substrates in a pig model. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2023, 9, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, M.; Zhang, H.; Xu, J.; Su, Y.; Zhu, W. Feeding frequency affects the growth performance, nutrient digestion and absorption of growing pigs with the same daily feed intake. Livest. Sci. 2021, 250, 104558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Cao, S.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Liu, J. Reduced meal frequency alleviates high-fat diet-induced lipid accumulation and inflammation in adipose tissue of pigs under the circumstance of fixed feed allowance. Eur. J. Nutr. 2020, 59, 595–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacArthur Clark, J.A.; Sun, D. Guidelines for the ethical review of laboratory animal welfare People’s Republic of China National Standard GB/T 35892-2018 [Issued 6 February 2018 Effective from 1 September 2018]. Anim. Models Exp. Med. 2020, 3, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Research Council (U.S.); Committee on Nutrient Requirements of Swine. Nutrient Requirements of Swine; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Bai, S.; Ding, X.; Wang, J.; Zeng, Q.; Su, Z.; Xuan, Y.; Zhang, K. Nitrogen-corrected apparent metabolizable energy value of corn distillers dried grains with solubles for laying hens. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2018, 238, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florea, L.; Song, L.; Salzberg, S.L. Thousands of exon skipping events differentiate among splicing patterns in sixteen human tissues. F1000Research 2013, 2, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, D.W.; Sherman, B.T.; Lempicki, R.A. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat. Protoc. 2009, 4, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.W.; Kim, K.-T. Expression of genes involved in axon guidance: How much have we learned? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasmi, M.; Sellami, M.; Denham, J.; Padulo, J.; Kuvacic, G.; Selmi, W.; Khalifa, R. Time-restricted feeding influences immune responses without compromising muscle performance in older men. Nutrition 2018, 51, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zou, Q.; Zhao, B.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, W.; Li, Y.; Liu, R.; Liu, X.; Liu, Z. Effects of alternate-day fasting, time-restricted fasting and intermittent energy restriction DSS-induced on colitis and behavioral disorders. Redox Biol. 2020, 32, 101535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Naou, T.; Le Floc’H, N.; Louveau, I.; Van Milgen, J.; Gondret, F. Meal frequency changes the basal and time-course profiles of plasma nutrient concentrations and affects feed efficiency in young growing pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 2014, 92, 2008–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundaram, S.; Yan, L. Time-restricted feeding reduces adiposity in mice fed a high-fat diet. Nutr. Res. 2016, 36, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgado-Delgado, R.; Angeles-Castellanos, M.; Saderi, N.; Buijs, R.M.; Escobar, C. Food intake during the normal activity phase prevents obesity and circadian desynchrony in a rat model of night work. Endocrinology 2010, 151, 1019–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abelilla, J.J.; Stein, H.H. Degradation of dietary fiber in the stomach, small intestine, and large intestine of growing pigs fed corn-or wheat-based diets without or with microbial xylanase. J. Anim. Sci. 2019, 97, 338–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Chen, D.; Tian, G.; Zheng, P.; Mao, X.; Yu, J.; He, J.; Huang, Z.; Luo, Y.; Luo, J. Effects of soluble and insoluble dietary fiber supplementation on growth performance, nutrient digestibility, intestinal microbe and barrier function in weaning piglet. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2020, 260, 114335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keys, J., Jr.; DeBarthe, J. Cellulose and hemicellulose digestibility in the stomach, small intestine and large intestine of swine. J. Anim. Sci. 1974, 39, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Xia, P.; Lu, Z.; Su, Y.; Zhu, W. Metabolome-microbiome responses of growing pigs induced by time-restricted feeding. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 681202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Mao, Y.; Xu, G.; Liao, W.; Ren, J.; Yang, H.; Yang, J.; Sun, L.; Chen, H.; Wang, W. Time-restricted feeding causes irreversible metabolic disorders and gut microbiota shift in pediatric mice. Pediatr. Res. 2019, 85, 518–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rust, B.M.; Picklo, M.J.; Yan, L.; Mehus, A.A.; Zeng, H. Time-restricted feeding modifies the fecal lipidome and the gut microbiota. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boumans, I.J.; de Boer, I.J.; Hofstede, G.J.; la Fleur, S.E.; Bokkers, E.A. The importance of hormonal circadian rhythms in daily feeding patterns: An illustration with simulated pigs. Horm. Behav. 2017, 93, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, S.; Matthan, N.R.; Lamon-Fava, S.; Solano-Aguilar, G.; Turner, J.R.; Walker, M.E.; Chai, Z.; Lakshman, S.; Chen, C.; Dawson, H. Colon transcriptome is modified by a dietary pattern/atorvastatin interaction in the Ossabaw pig. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2021, 90, 108570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.A.; Han, D.H.; Noh, J.Y.; Kim, M.H.; Son, G.H.; Kim, K.; Kim, C.J.; Pak, Y.K.; Cho, S. Meal time shift disturbs circadian rhythmicity along with metabolic and behavioral alterations in mice. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e44053. [Google Scholar]

- Beccuti, G.; Monagheddu, C.; Evangelista, A.; Ciccone, G.; Broglio, F.; Soldati, L.; Bo, S. Timing of food intake: Sounding the alarm about metabolic impairments? A systematic review. Pharmacol. Res. 2017, 125, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P.; Turek, F.W. Timing of meals: When is as critical as what and how much. Am. J. Physiol.-Endocrinol. Metab. 2017, 312, E369–E380. [Google Scholar]

- Ekmekcioglu, C.; Touitou, Y. Chronobiological aspects of food intake and metabolism and their relevance on energy balance and weight regulation. Obes. Rev. 2011, 12, 14–25. [Google Scholar]

- Lundell, L.S.; Parr, E.B.; Devlin, B.L.; Ingerslev, L.R.; Altıntaş, A.; Sato, S.; Sassone-Corsi, P.; Barrès, R.; Zierath, J.R.; Hawley, J.A. Time-restricted feeding alters lipid and amino acid metabolite rhythmicity without perturbing clock gene expression. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4643. [Google Scholar]

- Daas, M.; De Roos, N. Intermittent fasting contributes to aligned circadian rhythms through interactions with the gut microbiome. Benef. Microbes 2021, 12, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Index | Segment | Treatment | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FA | TRF | |||

| Length (m) | Jejunum | 17.76 ± 0.85 | 19.10 ± 0.41 | 0.067 |

| Colon | 3.97 ± 0.21 | 4.32 ± 0.15 | 0.188 | |

| Organ index (%) | Jejunum | 2.78 ± 0.14 | 2.84 ± 0.18 | 0.803 |

| Colon | 2.57 ± 0.15 | 2.71 ± 0.33 | 0.721 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, H.; Shan, H.; Wei, X.; Su, Y. Segment-Specific Functional Responses of Swine Intestine to Time-Restricted Feeding Regime. Animals 2026, 16, 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010052

Wang H, Shan H, Wei X, Su Y. Segment-Specific Functional Responses of Swine Intestine to Time-Restricted Feeding Regime. Animals. 2026; 16(1):52. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010052

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Hongyu, Haoshu Shan, Xing Wei, and Yong Su. 2026. "Segment-Specific Functional Responses of Swine Intestine to Time-Restricted Feeding Regime" Animals 16, no. 1: 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010052

APA StyleWang, H., Shan, H., Wei, X., & Su, Y. (2026). Segment-Specific Functional Responses of Swine Intestine to Time-Restricted Feeding Regime. Animals, 16(1), 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010052