Long-Term Saccharomyces cerevisiae Supplementation Enhances Milk Yield and Reproductive Performance in Lactating Dairy Cows on Smallholder Farms

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Experimental Design

2.2. Diet, Feeding Management, and Feed Sample

2.3. Blood Sampling and Progesterone Analysis

2.4. Milk Sampling and Somatic Cell Count

2.5. Estrus Detection and Artificial Insemination

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Growth Performance and Nutrient Intake Parameters

3.2. Milk Yield and Composition

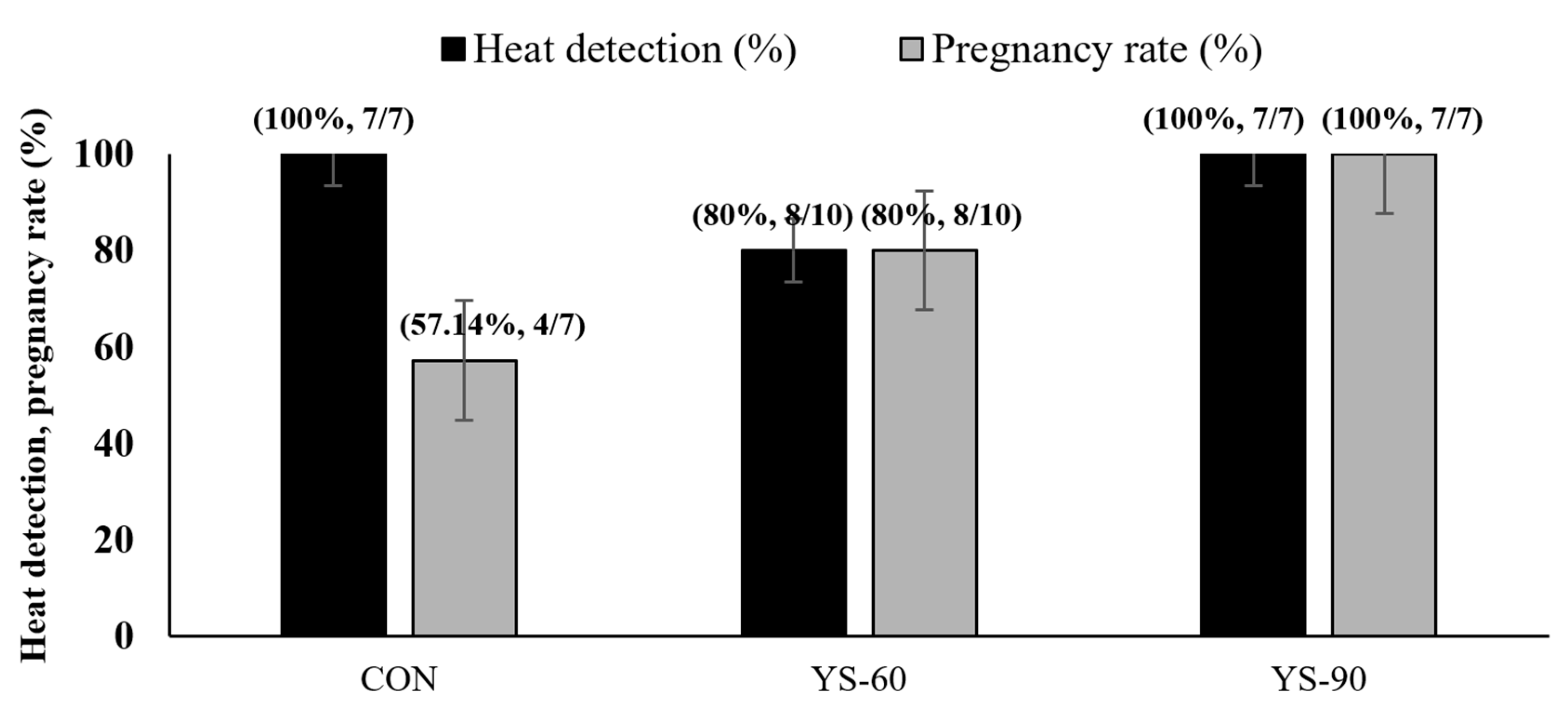

3.3. Heat Detection and Pregnancy Rates

3.4. Progesterone Concentration

3.5. Somatic Cell Count over Time

4. Discussion

4.1. Growth Performance and Nutrient Intake Parameters

4.2. Milk Yield and Composition

4.3. Reproductive Performance

4.4. Progesterone Concentration

4.5. Somatic Cell Count over Time

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Roche, J.R.; Friggens, N.C.; Kay, J.K.; Fisher, M.W.; Stafford, K.J.; Berry, D.P. Invited review: Body condition score and its association with dairy cow productivity, health, and welfare. J. Dairy Sci. 2009, 92, 5769–5801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, W.R. Energy balance relationships with follicular development, ovulation and fertility in postpartum dairy cows. Livest. Prod. Sci. 2003, 83, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallini, D.; Lamanna, M.; Colleluori, R.; Silvestrelli, S.; Ghiaccio, F.; Buonaiuto, G.; Formigoni, A. The use of rumen-protected amino acids and fibrous by-products can increase the sustainability of milk production. Front. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 1588425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magro, S.; Costa, A.; Cavallini, D.; Chiarin, E.; De Marchi, M. Phenotypic variation of dairy cows’ hematic metabolites and feasibility of non-invasive monitoring of the metabolic status in the transition period. Front. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 1437352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaucheyras-Durand, F.; Walker, N.D.; Bach, A. Effects of active dry yeasts on the rumen microbial ecosystem: Past, present and future. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2008, 145, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattaneo, L.; Lopreiato, V.; Piccioli-Cappelli, F.; Trevisi, E.; Minuti, A. Effect of supplementing live Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeast on performance, rumen function, and metabolism during the transition period in Holstein dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2023, 106, 4353–4365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, N.P.; Poletti, G.; Chesini, R.G.; Grigoletto, N.T.S.; Costa, B.C.; da Silva, G.G.; Nunes, A.T.; Takiya, C.S.; Durman, T.; Costa e Silva, L.F.; et al. Enhancing productive performance in dairy cows through supplementation of a blend of essential oils and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Dairy Sci. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tristant, D.; Moran, C.A. The efficacy of feeding a live probiotic yeast, Yea-Sacc®, on the performance of lactating dairy cows. J. Appl. Anim. Nutr. 2015, 3, e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zicarelli, F.; Iommelli, P.; Musco, N.; Wanapat, M.; Lotito, D.; Lombardi, P.; Infascelli, F.; Tudisco, R. Growth performance of buffalo calves in response to different diets with and without Saccharomyces cerevisiae supplementation. Animals 2024, 14, 1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halfen, J.; Carpinelli, N.; Del Pino, F.A.B.; Chapman, J.D.; Sharman, E.D.; Anderson, J.L.; Osorio, J.S. Effects of yeast culture supplementation on lactation performance and rumen fermentation profile and microbial abundance in mid-lactation Holstein dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 11580–11592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hristov, A.N.; Varga, G.; Cassidy, T.; Long, M.; Heyler, K.; Karnati, S.K.R.; Corl, B.; Hovde, C.J.; Yoon, I. Effect of Saccharomyces cerevisiae fermentation product on ruminal fermentation and nutrient utilization in dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2010, 93, 682–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amin, A.B.; Mao, S. Influence of yeast on rumen fermentation, growth performance and quality of products in ruminants: A review. Anim. Nutr. 2021, 7, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stein, D.R.; Allen, D.T.; Perry, E.B.; Bruner, J.C.; Gates, K.W.; Rehberger, T.G.; Mertz, K.; Jones, D.; Spicer, L.J. Effects of feeding Propionibacteria to dairy cows on milk yield, milk components, and reproduction. J. Dairy Sci. 2006, 89, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Q.; Xiao, Y.; Sun, P. Rumen–mammary gland axis and bacterial extracellular vesicles: Exploring a new perspective on heat stress in dairy cows. Anim. Nutr. 2024, 19, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinloche, E.; McEwan, N.; Marden, J.P.; Bayourthe, C.; Auclair, E.; Newbold, C.J. The effects of a probiotic yeast on the bacterial diversity and population structure in the rumen of cattle. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e67824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, M.A.; Penner, G.B.; Chaucheyras-Durand, F.; Guan, L.L. Development and physiology of the rumen and the lower gut: Targets for improving gut health. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 4955–4966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalla, K.; Manda, N.K.; Dhillon, H.S.; Kanade, S.R.; Rokana, N.; Hess, M.; Puniya, A.K. Impact of probiotics on dairy production efficiency. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 805963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Q.; Ma, F.T.; Jin, Y.H.; Gao, D.; Li, H.Y.; Sun, P. Chromium yeast alleviates heat stress by improving antioxidant and immune function in Holstein mid-lactation dairy cows. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2020, 269, 114635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Singh, N.K.; Bhadwal, M.S. Relationship of somatic cell count and mastitis: An overview. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2011, 24, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruegg, P.L. A 100-year review: Mastitis detection, management, and prevention. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 10381–10397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skórko-Sajko, H.; Sajko, J.; Zalewski, W. The effect of Yea-Sacc1026 in the ration for dairy cows on production and composition of milk. J. Anim. Feed Sci. 1993, 2, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnsworthy, P.C.; Saunders, N.; Goodman, J.R.; Algherair, I.H.; Ambrose, J.D. Effects of live yeast on milk yield, feed efficiency, methane emissions and fertility of high-yielding dairy cows. Animal 2025, 19, 101379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charan, J.; Kantharia, N.D. How to calculate sample size in animal studies? J. Pharmacol. Pharmacother. 2013, 4, 303–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daley, M.J.; Oldham, E.R.; Williams, T.J.; Coyle, P.A. Quantitative and qualitative properties of host polymorphonuclear cells during experimentally induced Staphylococcus aureus mastitis in cows. Am. J. Vet. Res. 1991, 52, 474–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Liu, Y.C.; Wang, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, X.M.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, D.R.; Gao, S.; Qi, Z.L. Impact of yeast and lactic acid bacteria on mastitis and milk microbiota composition of dairy cows. AMB Express 2020, 10, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Khan, A. Basic facts of mastitis in dairy animals: A review. Pak. Vet. J. 2006, 26, 204–208. [Google Scholar]

- Edmonson, A.J.; Lean, I.J.; Weaver, L.D.; Farver, T.; Webster, G. A body condition scoring chart for Holstein dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 1989, 72, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Research Council (NRC). Nutrient Requirements of Dairy Cattle, 7th ed.; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis, 16th ed.; Association of Official Analytical Chemists: Arlington, VA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Van Soest, P.J.; Robertson, J.B.; Lewis, B.A. Methods for dietary fiber, neutral detergent fiber, and nonstarch polysaccharides in relation to animal nutrition. J. Dairy Sci. 1991, 74, 3583–3597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navanukraw, C.; Khanthusaeng, V.; Kraisoon, A.; Uriyapongson, S. Estrous and ovulatory responses following cervical artificial insemination in Thai-native goats given a new or once-used controlled internal drug release with human chorionic gonadotropin. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2014, 46, 1441–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philpot, W.N.; Nickerson, S.C. Mastitis: Counter Attack: A Strategy to Combat Mastitis; Badson Brothers Co.: Oak Brook, IL, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Diskin, M.G.; Sreenan, J.M. Expression and detection of oestrus in cattle. Reprod. Nutr. Dev. 2000, 40, 481–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Huang, J.; Zhang, H.; Song, X.; Jiang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Shen, X. Live yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) improves growth performance and liver metabolic status of lactating Hu sheep. J. Dairy Sci. 2025, 108, 3700–3715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilachai, K.; Paengkoum, P.; Taethaisong, N.; Thitisak, P.; Poonsuk, K.; Loor, J.J.; Paengkoum, S. Effect of isolation ruminal yeast from ruminants on in vitro ruminal fermentation. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Wang, X.; Cheng, H.; Yin, W.; An, Y.; Li, M.; Chen, X.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhen, Y. Effect of yeast culture supplementation on rumen microbiota, regulation pathways, and milk production in dairy cows of different parities. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2025, 321, 116244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamalamma; Krishnamoorthy, U.; Krishnappa, P. Effect of feeding yeast culture (Yea-sacc1026) on rumen fermentation in vitro and production performance in crossbred dairy cows. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 1996, 57, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumprechtová, D.; Legendre, H.; Kadek, R.; Nenov, V.; Briche, M.; Salah, N.; Illek, J. Dose effect of Actisaf Sc 47 yeast probiotic (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) supplementation on production, reproduction, and negative energy balance in early lactation dairy cows. Transl. Anim. Sci. 2023, 8, txad132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broderick, G.A.; Stevenson, M.J.; Patton, R.A. Effect of dietary protein concentration and degradability on response. J. Dairy Sci. 2009, 92, 2719–2728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, K.; Mendonça, L.G.D.; Hulbert, L.E.; Mamedova, L.K.; Muckey, M.B.; Shen, Y.; Elrod, C.C.; Bradford, B.J. Yeast product supplementation modulated humoral and mucosal immunity and uterine inflammatory signals in transition dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2015, 98, 3236–3246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bionaz, M.; Trevisi, E.; Calamari, L.; Librandi, F.; Ferrari, A.; Bertoni, G. Plasma paraoxonase, health, inflammatory conditions, and liver function in transition dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2007, 90, 1740–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, A.R.; Di Rienzo, J.A.; Cavallini, D. Effect of a mix of condensed and hydrolysable tannins feed additive on lactating dairy cows’ services per conception and days open. Vet. Anim. Sci. 2025, 27, 100434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, A.R.; Pol, M.; Gaggiotti, M.; Di Rienzo, J.A.; Cavallini, D. Effect of a feed additive based on a mix of condensed and hydrolysable tannins (ByPro®) on lactating dairy cows milk production performance. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2025, 57, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | Dry Matter (kg) |

|---|---|

| Chopped rice straw | 19.50 |

| Cassava chip | 35.30 |

| Wet cassava pulp | 5.00 |

| Dried brewer’s grain | 10.00 |

| Soybean meal (44% CP) | 17.00 |

| Ground corn | 11.00 |

| Urea | 1.50 |

| Premix 1 | 0.50 |

| Sulfur powder | 0.10 |

| Sodium bicarbonate | 0.10 |

| Total | 100.00 |

| Cost (USD/kg) | 0.27 |

| Chemical composition | |

| Dry matter (DM, %) | 74.50 |

| % Dry matter | |

| Organic matter | 88.12 |

| Crude protein | 16.94 |

| Ether extract | 4.34 |

| Neutral detergent fiber | 24.70 |

| Acid detergent fiber | 16.20 |

| Non-fiber carbohydrate | 42.14 |

| Total digestible nutrient | 79.10 |

| Item | Live Yeast Supplement | SEM | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CON | YS-60 | YS-90 | |||

| Number of cows | 7 | 10 | 7 | ||

| Initial body weight (kg) | 412.57 | 416.40 | 419.86 | 5.95 | 0.7206 |

| Final body weight (kg) | 416.43 b | 432.21 a | 448.57 a | 3.70 | 0.0001 |

| Body weight gain (kg) | 3.86 c | 16.02 b | 28.71 a | 4.53 | 0.0018 |

| Body condition score | 2.49 b | 2.60 b | 2.75 a | 0.04 | 0.0001 |

| Dry matter intake (kg/day) | 8.58 c | 8.83 b | 9.03 a | 0.09 | 0.0001 |

| Dry matter intake (%BW) | 2.08 | 2.12 | 2.15 | 0.03 | 0.2586 |

| Dry matter intake (g/kg BW0.75) | 93.72 b | 95.92 ab | 98.06 a | 0.50 | 0.0436 |

| Item | Live Yeast Supplement | SEM | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CON | YS-60 | YS-90 | |||

| Milk yield (kg/day) | 19.75 c | 20.48 b | 21.94 a | 0.35 | 0.0001 |

| Milk composition, % | |||||

| Fat | 3.51 b | 3.63 a | 3.73 a | 0.04 | 0.0001 |

| Protein | 3.14 | 3.17 | 3.18 | 0.12 | 0.1295 |

| Lactose | 4.26 b | 4.71 a | 4.76 a | 0.06 | 0.0003 |

| Solid not fat | 8.63 | 8.64 | 8.58 | 0.12 | 0.3261 |

| Total solid | 12.15 | 12.27 | 12.31 | 0.35 | 0.2518 |

| Fat: protein | 1.12 | 1.15 | 1.17 | 0.03 | 0.5243 |

| Log10 somatic cell count | 1.80 a | 1.85 a | 1.42 b | 0.07 | 0.0024 |

| Feed efficiency | |||||

| kg milk/kg feed DM | 2.31 | 2.30 | 2.35 | 0.03 | 0.8320 |

| ECM (kg/day) | 18.18 c | 19.20 b | 20.86 a | 0.35 | 0.0001 |

| Cost (USD/day) | 8.92 c | 9.35 b | 9.88 a | 0.02 | 0.0001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Suayroop, N.; Khanthusaeng, V.; Kraisoon, A.; Bunma, T.; Nabthonglang, J.; Navanukraw, P.; Haitook, T.; Cherdthong, A.; Navanukraw, C. Long-Term Saccharomyces cerevisiae Supplementation Enhances Milk Yield and Reproductive Performance in Lactating Dairy Cows on Smallholder Farms. Animals 2026, 16, 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010032

Suayroop N, Khanthusaeng V, Kraisoon A, Bunma T, Nabthonglang J, Navanukraw P, Haitook T, Cherdthong A, Navanukraw C. Long-Term Saccharomyces cerevisiae Supplementation Enhances Milk Yield and Reproductive Performance in Lactating Dairy Cows on Smallholder Farms. Animals. 2026; 16(1):32. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010032

Chicago/Turabian StyleSuayroop, Naritsara, Vilaivan Khanthusaeng, Aree Kraisoon, Thanya Bunma, Juthamas Nabthonglang, Pakpoom Navanukraw, Theerachai Haitook, Anusorn Cherdthong, and Chainarong Navanukraw. 2026. "Long-Term Saccharomyces cerevisiae Supplementation Enhances Milk Yield and Reproductive Performance in Lactating Dairy Cows on Smallholder Farms" Animals 16, no. 1: 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010032

APA StyleSuayroop, N., Khanthusaeng, V., Kraisoon, A., Bunma, T., Nabthonglang, J., Navanukraw, P., Haitook, T., Cherdthong, A., & Navanukraw, C. (2026). Long-Term Saccharomyces cerevisiae Supplementation Enhances Milk Yield and Reproductive Performance in Lactating Dairy Cows on Smallholder Farms. Animals, 16(1), 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010032