Bile Culture, Antimicrobial Susceptibility, and Hepatobiliary Pathology in Dogs Undergoing Cholecystectomy for Gallbladder Mucocele

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Case Selection

2.2. Data Collection and Variables

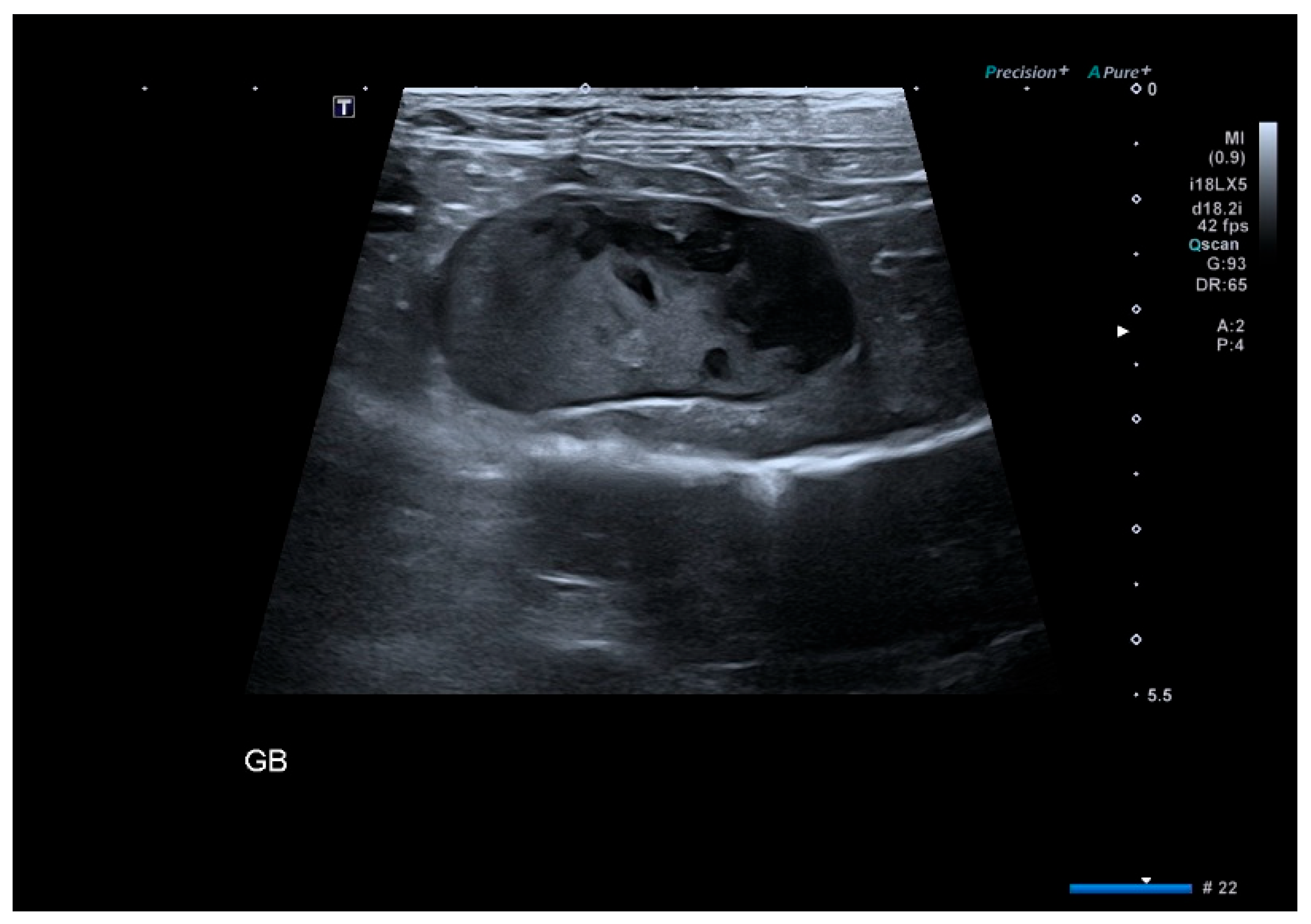

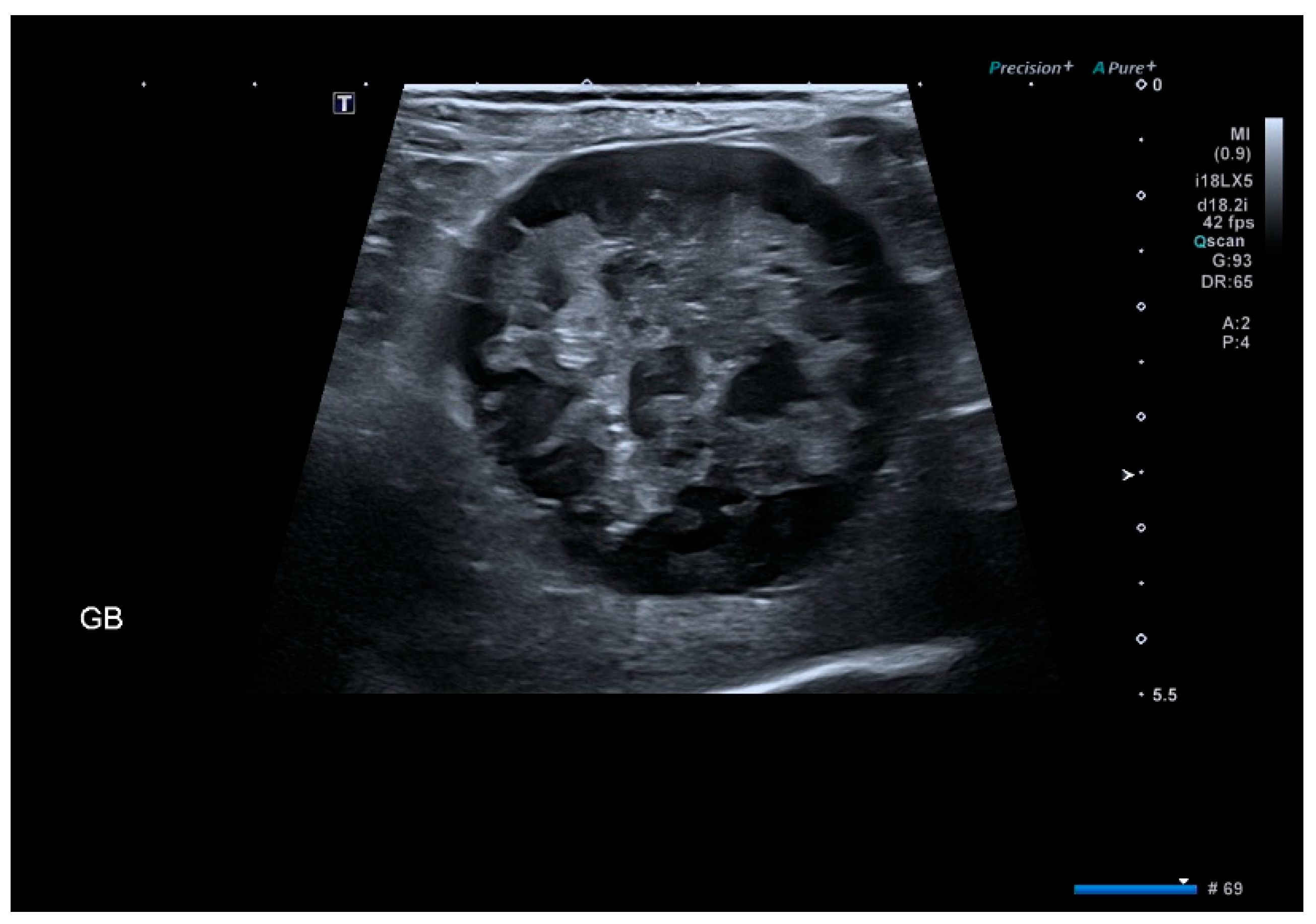

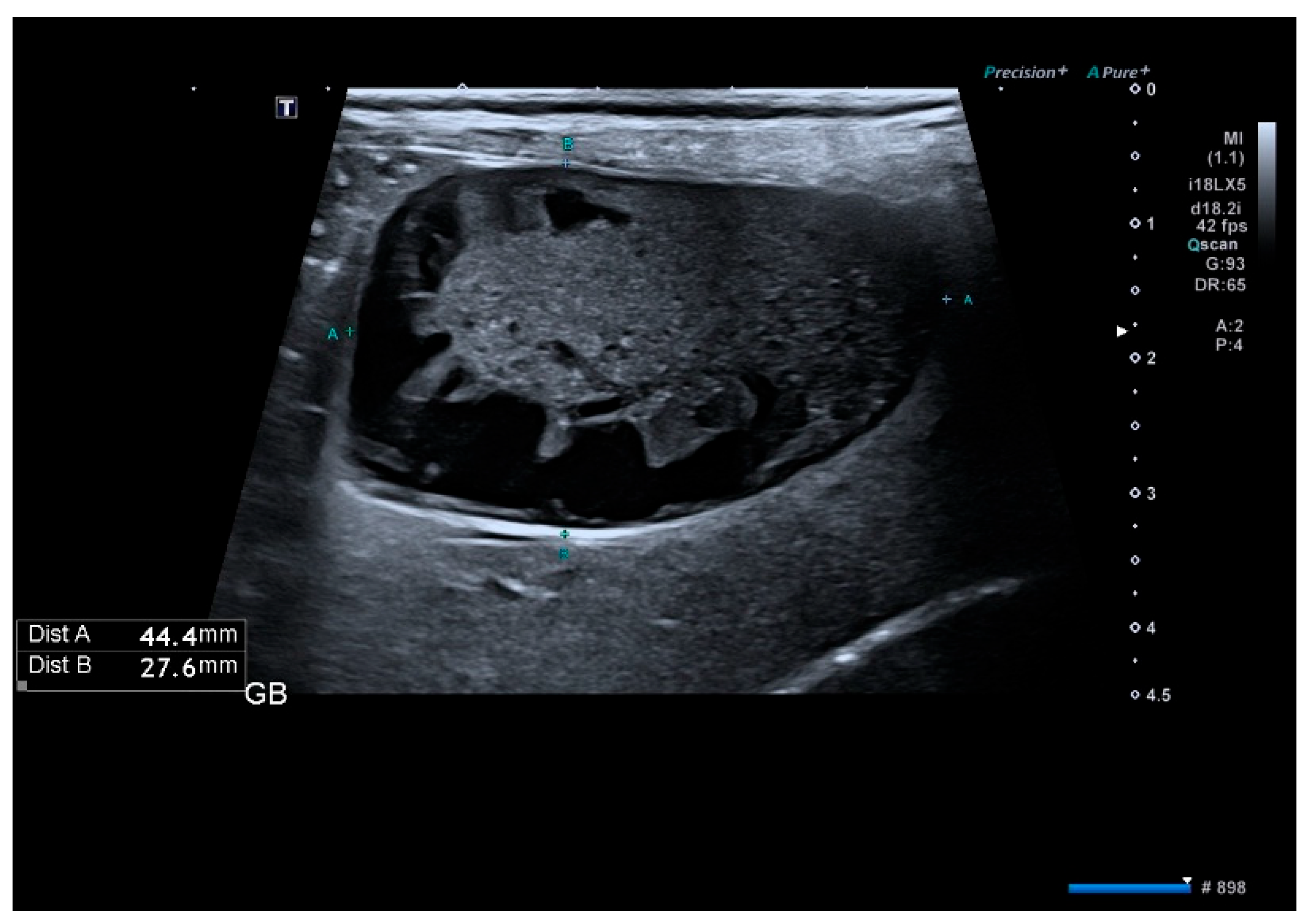

2.3. Imaging Evaluation

2.4. Microbiologic Analysis

2.5. Antimicrobial Resistance Classification

2.6. Postoperative Outcomes and Definitions

2.7. Histopathological Evaluation

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics of Dogs Undergoing Cholecystectomy

3.2. Preoperative Laboratory Findings

3.3. Ultrasound Findings

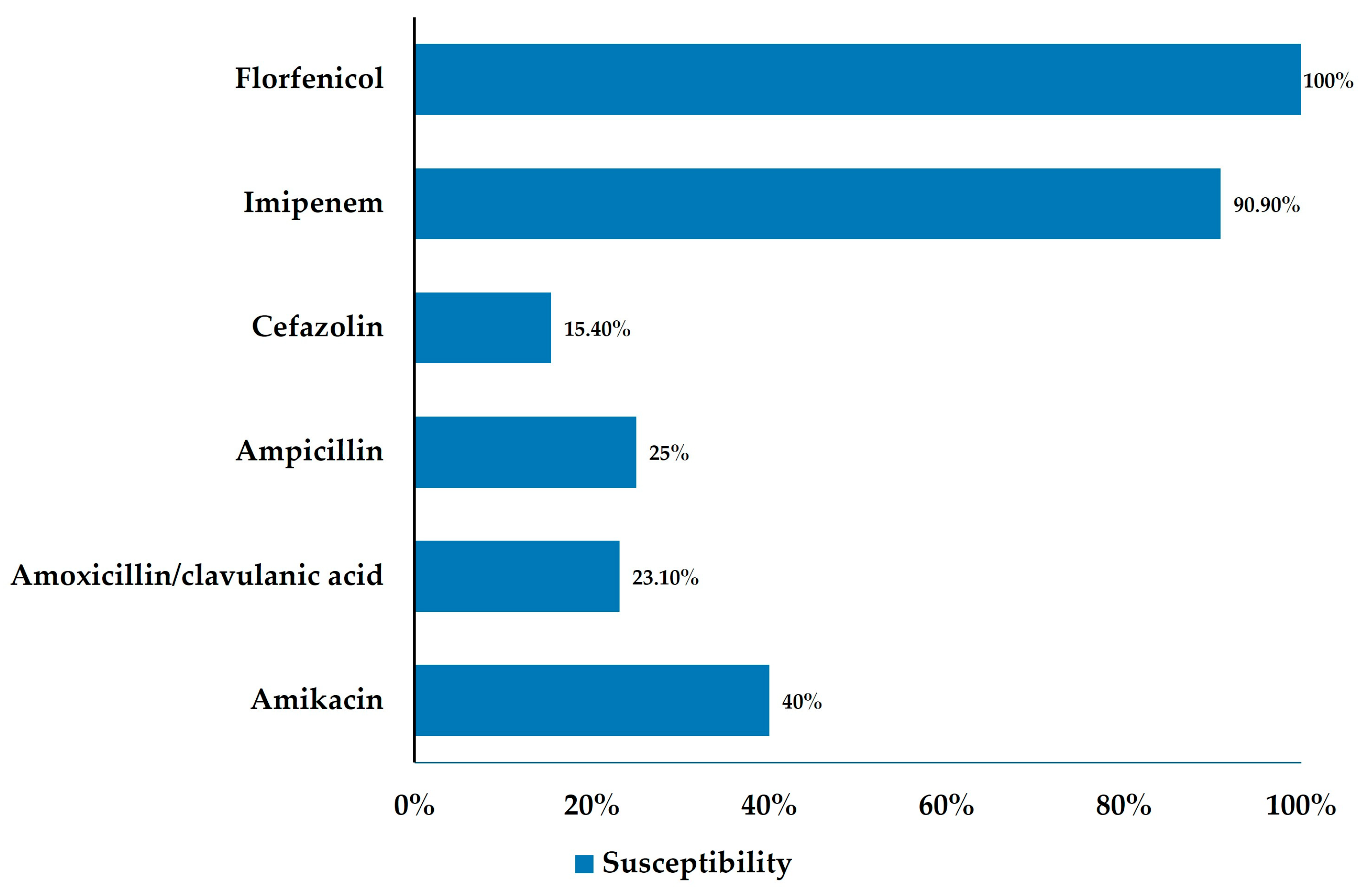

3.4. Bile Culture and Antimicrobial Resistance

3.5. Antibiotic Matching and Postoperative Outcomes

3.6. Histopathology of Gallbladder and Liver

3.7. Breed Predisposition: Over-Representation of Toy Poodles

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ALT | Alanine aminotransferase |

| ALP | Alkaline phosphatase |

| AST | Aspartate aminotransferase |

| GGT | Gamma-glutamyl transferase |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| T-bil | Total bilirubin |

| ASA | American Society of Anesthesiologists |

| GBM | Gallbladder mucocele |

| MDR | Multidrug-resistant |

| XDR | Extensively drug-resistant |

| AMR | Antimicrobial resistance |

| AST (test) | Antimicrobial susceptibility testing |

| EUCAST | European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing |

| CLSI | Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute |

| IACUC | Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee |

| LOS | Length of stay |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

References

- Pike, F.S.; Berg, J.; King, N.W.; Penninck, D.G.; Webster, C.R. Gallbladder mucocele in dogs: 30 cases (2000–2002). J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2004, 224, 1615–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffey, J.A.; Pavlick, M.; Webster, C.R.; Moore, G.E.; McDaniel, K.A.; Blois, S.L. Effect of clinical signs, endocrinopathies, timing of surgery, hyperlipidemia, and hyperbilirubinemia on outcome in dogs with gallbladder mucocele. Vet. J. 2019, 251, 105350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffey, J.A.; Kim, R.H.; Kim, S.; Lee, Y.J.; Lim, C.H.; Lee, L.L. Ultrasonographic patterns, clinical findings, and prognostic variables in dogs from Asia with gallbladder mucocele. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2022, 36, 565–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernon, T.L.; Fleming, E.J.; Cullen, G.; Barker, V.; Miller, L.B. The effect of flushing of the common bile duct on hepatobiliary markers and short-term outcomes in dogs undergoing cholecystectomy for the management of gall bladder mucocele: A randomized controlled prospective study. Vet. Surg. 2023, 52, 697–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossanese, M.; Williams, P.; Tomlinson, A.; Cinti, F. Long-term outcome after cholecystectomy without common bile duct catheterization and flushing in dogs. Animals 2022, 12, 2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Youn, G.; Waschak, M.J.; Kunkel, K.A.R.; Gerard, P.D. Outcome of elective cholecystectomy for the treatment of gallbladder disease in dogs. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2018, 252, 970–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brodbelt, D.C.; Blissitt, K.J.; Hammond, R.A.; Neath, P.J.; Yarrow, L.E.; Pfeiffer, D.U. The risk of death: The confidential enquiry into perioperative small animal fatalities. Vet. Anaesth. Analg. 2008, 35, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, N.S.; Mohn, T.J.; Yang, M.; Spofford, N.; Marsh, A.; Faunt, K.; Lund, E.M.; Lefebvre, S.L. Factors associated with anesthetic-related death in dogs and cats in primary care veterinary hospitals. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2017, 250, 655–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyson, D.H. Perioperative monitoring and support of the small animal patient: ASA status and beyond. Can. Vet. J. 2017, 58, 447–455. [Google Scholar]

- Jablonski, S.A.; Chen, Y.X.P.; Williams, J.E.; Kendziorski, J.A.; Smedley, R.C. Concurrent hepatopathy in dogs with gallbladder mucocele: Prevalence, predictors, and impact on long-term outcome. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2024, 38, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, H.K.; Jeong, J.Y.; Lee, S.Y.; Hwang, H.M.; Shin, K.I.; Park, J.H.; Ji, S.Y.; Hong, Y.J. Clinical outcomes in dogs undergoing cholecystectomy via a transverse incision: A meta-analysis of 121 animals treated between 2011 and 2021. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allerton, F.; Swinbourne, F.; Barker, L.; Black, V.; Kathrani, A.; Tivers, M.; Henriques, T.; Kisielewicz, C.; Dunning, M.; Kent, A. Gall bladder mucoceles in Border Terriers. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2018, 32, 1618–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffey, J.A.; Graham, A.; VanEerde, E.; Hostnik, E.; Alvarez, W.; Arango, J.; Jacobs, C.; DeClue, A.E. Gallbladder mucocele: Variables associated with outcome and the utility of ultrasonography to identify gallbladder rupture in 219 dogs (2007–2016). J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2017, 31, 733–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gookin, J.L.; Correa, M.T.; Peters, A.; Malueg, A.; Mathews, K.G.; Cullen, J.; Seiler, G. Association of gallbladder mucocele histologic diagnosis with selected drug use in dogs: A matched case-control study. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2015, 29, 1464–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamborini, A.; Jahns, H.; McAllister, H.; Kent, A.; Harris, B.; Procoli, F.; Allenspach, K.; Hall, E.J.; Day, M.J.; Watson, P.J.; et al. Bacterial cholangitis, cholecystitis, or both in dogs. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2016, 30, 1046–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, K.A.; Hartmann, F.A.; Trepanier, L.A. Bacterial culture results from liver, gallbladder, or bile in 248 dogs and cats evaluated for hepatobiliary disease: 1998–2003. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2007, 21, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, F.I.; Shaw, J.P.; Ho, K.K.L.; Ng, O.; Brown, P.; Burgess, V.R. High frequency of cholecystitis in dogs with gallbladder mucocele in Hong Kong. Vet. J. 2022, 287, 105881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlachet, A.T.; Boulouis, H.J.; Beurlet-Lafarge, S.; Canonne, M.A. Antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of bacteria associated with hepatobiliary disease in dogs and cats (2010–2019). J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2025, 39, e70007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zogg, A.L.; Simmen, S.; Zurfluh, K.; Stephan, R.; Schmitt, S.N.; Nüesch-Inderbinen, M. High prevalence of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae among clinical isolates from cats and dogs admitted to a veterinary hospital in Switzerland. Front. Vet. Sci. 2018, 5, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutsunai, M.; Kanemoto, H.; Fukushima, K.; Fujino, Y.; Ohno, K.; Tsujimoto, H. The association between gall bladder mucoceles and hyperlipidaemia in dogs: A retrospective case-control study. Vet. J. 2014, 199, 76–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mealey, K.L.; Minch, J.D.; White, S.N.; Snekvik, K.R.; Mattoon, J.S. An insertion mutation in ABCB4 is associated with gallbladder mucocele formation in dogs. Comp. Hepatol. 2010, 9, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friesen, S.L.; Upchurch, D.A.; Hollenbeck, D.L.; Roush, J.K. Clinical findings for dogs undergoing elective and nonelective cholecystectomies for gall bladder mucoceles. J. Small Anim. Pract. 2021, 62, 547–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portier, K.; Ida, K.K. The ASA physical status classification: What is the evidence for recommending its use in veterinary anesthesia?—A systematic review. Front. Vet. Sci. 2018, 5, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Disk and Dilution Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria Isolated from Animals, 7th ed.; CLSI: Wayne, PA, USA, 2023; Available online: https://clsi.org/shop/standards/vet01s/ (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST). Breakpoint Tables for Interpretation of MICs and Zone Diameters; Version 14.0; EUCAST: Basel, Switzerland, 2024; Available online: https://www.eucast.org/clinical_breakpoints/ (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Magiorakos, A.P.; Srinivasan, A.; Carey, R.B.; Carmeli, Y.; Falagas, M.E.; Giske, C.G.; Harbarth, S.; Hindler, J.F.; Kahlmeter, G.; Olsson-Liljequist, B.; et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: An international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012, 18, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics, 6th ed.; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zar, J.H. Biostatistical Analysis, 5th ed.; Pearson Education India: New Delhi, India, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Weese, J.S.; Giguère, S.; Guardabassi, L.; Morley, P.S.; Papich, M.; Ricciuto, D.R. ACVIM consensus statement on therapeutic antimicrobial use in animals and antimicrobial resistance. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2019, 33, 1121–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guardabassi, L.; Schwarz, S.; Lloyd, D.H. Pet animals as reservoirs of antimicrobial-resistant bacteria. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2004, 54, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuerena, I.; Williams, N.J.; Nuttall, T.; Pinchbeck, G. Antimicrobial-resistant Escherichia coli in hospitalised companion animals and their hospital environment. J. Small Anim. Pract. 2016, 57, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 12.5 ± 3.0 (median 12.9) |

| Body weight, kg | 5.0 ± 2.8 (median 4.4) |

| Sex | SF 30 (46.2), MC 30 (46.2), M 3 (4.6), F 2 (3.1) |

| Comorbidity | Present 43 (66.2), Absent 22 (33.8) |

| High-risk ASA grade (≥III) | 45 (69.2) |

| Breed | Toy poodle 23 (35.4), Maltese 11 (16.9), Pomeranian 9 (13.8), Mixed 8 (12.3), Others 14 (21.5) |

| Parameter | Reference Range | Mean ± SD | Median | Above Ref (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALT (U/L) | 19–70 | 489.5 ± 617.8 | 167.7 | 72.3 |

| ALP (U/L) | 15–127 | 1022.6 ± 1485.6 | 454.9 | 72.3 |

| GGT (U/L) | 0–6 | 53.9 ± 70.1 | 24.6 | 87.1 |

| AST (U/L) | 15–43 | 127.0 ± 199.2 | 38.0 | 48.3 |

| T-bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0–0.4 | 1.17 ± 1.82 | 0.2 | 33.8 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 2.2–3.9 | 2.86 ± 0.49 | 2.86 | 7.8 |

| WBC (×103/µL) | 5.32–16.92 | 14.28 ± 7.74 | 13.5 | 32.3 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 0–9 | 76.1 ± 71.0 | 49 | 73.8 |

| Variable | Category | n (%) | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bile culture | Positive | 13/61 (21.3) | 11.3–31.2 | <0.001 |

| Negative (no growth) | 48/61 (78.7) | 66.9–87.1 | <0.001 | |

| Resistance classification | MDR | 7/61 (11.5) | 3.2–18.7 | 0.032 |

| XDR | 4/61 (6.6) | 2.0–12.5 | <0.001 | |

| Pan-susceptible | 2/61 (3.3) | 0.4–6.8 | <0.001 |

| Variable | Category | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Inflammation | None | 17 (32.7) |

| Mild | 22 (42.3) | |

| Moderate | 10 (19.2) | |

| Severe | 3 (5.8) | |

| Fibrosis | None | 44 (84.6) |

| Mild | 7 (13.5) | |

| Moderate | 1 (1.9) | |

| Mucosal hyperplasia | Present | 47 (90.4) |

| Bacteria on histology | Present | 0 (0.0) |

| Perforation | Present | 1 (1.9) |

| Variable | Category | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Hepatitis grade | None | 8 (38.1) |

| Mild | 3 (14.3) | |

| Moderate | 7 (33.3) | |

| Severe | 3 (14.3) | |

| Cholangiopathy grade | None | 8 (38.1) |

| Mild | 6 (28.6) | |

| Moderate | 7 (33.3) | |

| Fibrosis stage | None | 9 (42.9) |

| Mild | 3 (14.3) | |

| Moderate | 5 (23.8) | |

| Severe | 4 (19.0) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Choe, J.-M.; Kim, H.; Hwang, J.; Kim, H.-Y. Bile Culture, Antimicrobial Susceptibility, and Hepatobiliary Pathology in Dogs Undergoing Cholecystectomy for Gallbladder Mucocele. Animals 2026, 16, 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010031

Choe J-M, Kim H, Hwang J, Kim H-Y. Bile Culture, Antimicrobial Susceptibility, and Hepatobiliary Pathology in Dogs Undergoing Cholecystectomy for Gallbladder Mucocele. Animals. 2026; 16(1):31. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010031

Chicago/Turabian StyleChoe, Ji-Min, Hyoju Kim, Jeonyeon Hwang, and Hwi-Yool Kim. 2026. "Bile Culture, Antimicrobial Susceptibility, and Hepatobiliary Pathology in Dogs Undergoing Cholecystectomy for Gallbladder Mucocele" Animals 16, no. 1: 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010031

APA StyleChoe, J.-M., Kim, H., Hwang, J., & Kim, H.-Y. (2026). Bile Culture, Antimicrobial Susceptibility, and Hepatobiliary Pathology in Dogs Undergoing Cholecystectomy for Gallbladder Mucocele. Animals, 16(1), 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010031