The Impact of Precisely Controlled Pre-Freeze Cooling Rates on Post-Thaw Stallion Sperm

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Implications

2. Introduction

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Experimental Design

3.2. Animals

3.3. Semen Collection and Initial Evaluation

3.4. Semen Processing

3.5. Cooling Protocols

3.6. Cryopreservation and Thawing

3.7. Sperm Motility Assessment

3.8. Physiological Assays

3.8.1. Sperm Viability (Membrane Integrity)

3.8.2. Mitochondrial Membrane Potential

3.8.3. Oxidation Status

3.8.4. Acrosome Integrity

3.9. Statistical Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Initial Semen Characteristics

4.2. Motility and Kinematic Parameters

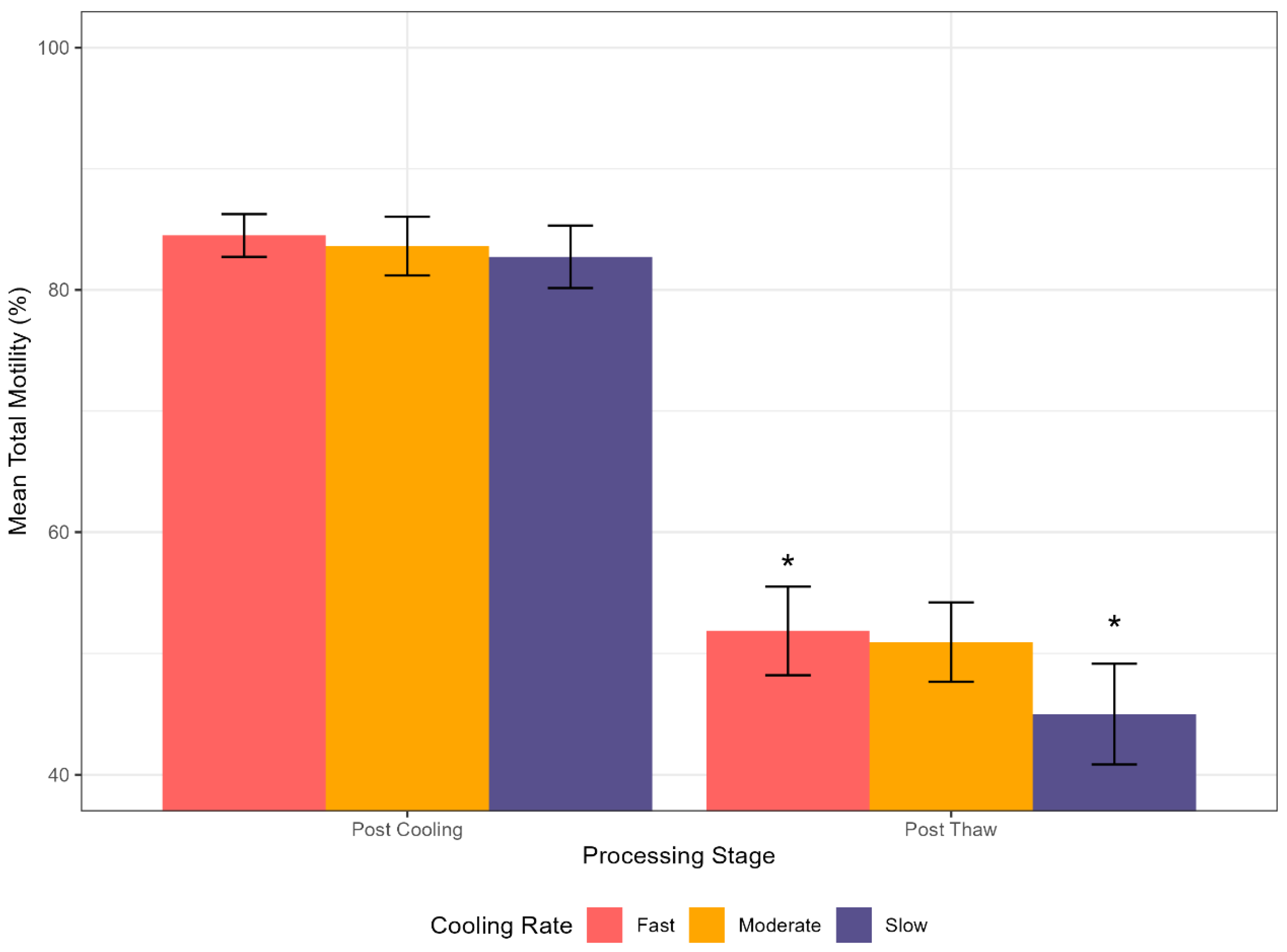

4.2.1. Total Motility

4.2.2. Progressive Motility and Kinematics

4.3. Sperm Physiological Markers

4.3.1. Viability and Acrosome Integrity

4.3.2. Mitochondrial and Oxidative Features

4.4. Summary of the Findings

5. Discussion

5.1. Resolution of the Cryobiological Paradox: Cold Shock Mitigation by Thermal Precision

5.2. Functional Implications and Interpretation of Motility Variation

- A.

- Proposed mechanism: Time-dependent injury and the performance of slow cooling

- B.

- Interpreting the viability trend and functional damage

5.3. Limitations and Future Perspectives

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Oldenbroek, J.K.; Windig, J.J. Opportunities of Genomics for the Use of Semen Cryo-Conserved in Gene Banks. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 907411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yánez-Ortiz, I.; Catalán, J.; Rodríguez-Gil, J.E.; Miró, J.; Yeste, M. Advances in Sperm Cryopreservation in Farm Animals: Cattle, Horse, Pig and Sheep. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2022, 246, 106904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loomis, P.R.; Graham, J.K. Commercial Semen Freezing: Individual Male Variation in Cryosurvival and the Response of Stallion Sperm to Customized Freezing Protocols. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2008, 105, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iacovides, S.; Prien, S. Cryoprotectants & Cryopreservation of Equine Semen: A Review of Industry Cryoprotectants and the Effects of Cryopreservation on Equine Semen Membranes. J. Dairy Vet. Anim. Res. 2016, 3, 00063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tischner, M. Evaluation of Deep-Frozen Semen in Stallions. J. Reprod. Fertil. Suppl. 1979, 53–59. [Google Scholar]

- Vidament, M. French Field Results (1985–2005) on Factors Affecting Fertility of Frozen Stallion Semen. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2005, 89, 115–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, M.J.; Arias, E.; Fuentes, F.; Muñoz, E.; Bernecic, N.; Fair, S.; Felmer, R. Cellular and Molecular Consequences of Stallion Sperm Cryopreservation: Recent Approaches to Improve Sperm Survival. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2023, 126, 104499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazur, P.; Leibo, S.P.; Chu, E.H.Y. A Two-Factor Hypothesis of Freezing Injury. Exp. Cell Res. 1972, 71, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieme, H.; Harrison, R.A.P.; Petrunkina, A.M. Cryobiological Determinants of Frozen Semen Quality, with Special Reference to Stallion. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2008, 107, 276–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, P.F.; Morris, G.J. Cold Shock Injury in Animal Cells. Symp. Soc. Exp. Biol. 1987, 41, 311–340. [Google Scholar]

- Zeron, Y.; Tomczak, M.; Crowe, J.; Arav, A. The Effect of Liposomes on Thermotropic Membrane Phase Transitions of Bovine Spermatozoa and Oocytes: Implications for Reducing Chilling Sensitivity. Cryobiology 2002, 45, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drobnis, E.Z.; Crowe, L.M.; Berger, T.; Anchordoguy, T.J.; Overstreet, J.W.; Crowe, J.H. Cold Shock Damage Is Due to Lipid Phase Transitions in Cell Membranes: A Demonstration Using Sperm as a Model. J. Exp. Zool. 1993, 265, 432–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moran, D.M.; Jasko, D.J.; Squires, E.L.; Amann, R.P. Determination of Temperature and Cooling Rate Which Induce Cold Shock in Stallion Spermatozoa. Theriogenology 1992, 38, 999–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devireddy, R.V.; Swanlund, D.J.; Olin, T.; Vincente, W.; Troedsson, M.H.T.; Bischof, J.C.; Roberts, K.P. Cryopreservation of Equine Sperm: Optimal Cooling Rates in the Presence and Absence of Cryoprotective Agents Determined Using Differential Scanning Calorimetry. Biol. Reprod. 2002, 66, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devireddy, R.; Swanlund, D.; Alghamdi, A.; Duoos, L.; Troedsson, M.; Bischof, J.; Roberts, K. Measured Effect of Collection and Cooling Conditions on the Motility and the Water Transport Parameters at Subzero Temperatures of Equine Spermatozoa. Reproduction 2002, 124, 643–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Critser, J.K. Mechanisms of Cryoinjury in Living Cells. ILAR J. 2000, 41, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aurich, C.; Schreiner, B.; Ille, N.; Alvarenga, M.; Scarlet, D. Cytosine Methylation of Sperm DNA in Horse Semen after Cryopreservation. Theriogenology 2016, 86, 1347–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopeika, J.; Thornhill, A.; Khalaf, Y. The Effect of Cryopreservation on the Genome of Gametes and Embryos: Principles of Cryobiology and Critical Appraisal of the Evidence. Hum. Reprod. Update 2015, 21, 209–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curry, M.R. Cryopreservation of Mammalian Semen. In Cryopreservation and Freeze-Drying Protocols; Day, J.G., Stacey, G.N., Eds.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2007; pp. 303–311. ISBN 978-1-59745-362-2. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, M.; Hu, M.; Cai, G.; Wei, H.; Huang, S.; Zheng, E.; Wu, Z. Overcoming Ice: Cutting-Edge Materials and Advanced Strategies for Effective Cryopreservation of Biosample. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2025, 23, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arav, A. Cryopreservation by Directional Freezing and Vitrification Focusing on Large Tissues and Organs. Cells 2022, 11, 1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macías García, B.; Ortega Ferrusola, C.; Aparicio, I.M.; Miró-Morán, A.; Morillo Rodriguez, A.; Gallardo Bolaños, J.M.; González Fernández, L.; Balao da Silva, C.M.; Rodríguez Martínez, H.; Tapia, J.A.; et al. Toxicity of Glycerol for the Stallion Spermatozoa: Effects on Membrane Integrity and Cytoskeleton, Lipid Peroxidation and Mitochondrial Membrane Potential. Theriogenology 2012, 77, 1280–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salazar, J.L.; Teague, S.R.; Love, C.C.; Brinsko, S.P.; Blanchard, T.L.; Varner, D.D. Effect of Cryopreservation Protocol on Postthaw Characteristics of Stallion Sperm. Theriogenology 2011, 76, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peña, F.J.; Macías García, B.; Samper, J.C.; Aparicio, I.M.; Tapia, J.A.; Ortega Ferrusola, C. Dissecting the Molecular Damage to Stallion Spermatozoa: The Way to Improve Current Cryopreservation Protocols? Theriogenology 2011, 76, 1177–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, D.Y.; Liu, J.; Liu, C.; McGann, L.E.; Watson, P.F.; Kleinhans, F.W.; Mazur, P.; Critser, E.S.; Critser, J.K. Andrology: Prevention of Osmotic Injury to Human Spermatozoa during Addition and Removal of Glycerol*. Hum. Reprod. 1995, 10, 1109–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arav, A.; Natan, D. Directional Freezing of Reproductive Cells and Organs. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2012, 47, 193–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arav, A.; Saragusty, J. Directional Freezing of Sperm and Associated Derived Technologies. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2016, 169, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saragusty, J.; Gacitua, H.; Pettit, M.; Arav, A. Directional Freezing of Equine Semen in Large Volumes. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2007, 42, 610–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komsky-Elbaz, A.; Roth, Z. Fluorimetric Techniques for the Assessment of Sperm Membranes. J. Vis. Exp. JoVE 2018, e58622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demyda-Peyrás, S.; Bottrel, M.; Acha, D.; Ortiz, I.; Hidalgo, M.; Carrasco, J.J.; Gómez-Arrones, V.; Gósalvez, J.; Dorado, J. Effect of Cooling Rate on Sperm Quality of Cryopreserved Andalusian Donkey Spermatozoa. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2018, 193, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arav, A. Device and Methods for Multigradient Directional Cooling and Warming of Biological Samples. U.S. Patent 5,873,254, 23 February 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kalo, D.; Reches, D.; Netta, N.; Komsky-Elbaz, A.; Zeron, Y.; Moallem, U.; Roth, Z. Carryover Effects of Feeding Bulls with an Omega-3-Enriched-Diet—From Spermatozoa to Developed Embryos. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0265650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogan, T.; Dahan, D.G.; Laor, R.; Argov-Argaman, N.; Zeron, Y.; Komsky-Elbaz, A.; Kalo, D.; Roth, Z. Association between Fatty Acid Composition, Cryotolerance and Fertility Competence of Progressively Motile Bovine Spermatozoa. Animals 2021, 11, 2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, P.J. A Lipid-Phase Separation Model of Low-Temperature Damage to Biological Membranes. Cryobiology 1985, 22, 128–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arav, A.; Zeron, Y.; Leslie, S.B.; Behboodi, E.; Anderson, G.B.; Crowe, J.H. Phase Transition Temperature and Chilling Sensitivity of Bovine Oocytes. Cryobiology 1996, 33, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, I.T.; Maddock, C.; Farnworth, M.; Nankervis, K.; Perrett, J.; Pyatt, A.Z.; Blanchard, R.N. Temporal Trends in Equine Sperm Progressive Motility: A Systematic Review and Meta-Regression. Reprod. Camb. Engl. 2023, 165, M1–M10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieme, H.; Oldenhof, H.; Wolkers, W. Sperm Membrane Behaviour during Cooling and Cryopreservation. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2015, 50, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baust, J.M.; Campbell, L.H.; Harbell, J.W. Best Practices for Cryopreserving, Thawing, Recovering, and Assessing Cells. Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol.-Anim. 2017, 53, 855–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | N | Mean | SEM | Median | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concentration (×106/mL) | 15 | 151.27 | 11.01 | 171.02 | 59.04 | 213.41 |

| Total motility (%) | 15 | 87.63 | 1.72 | 89.55 | 70.40 | 94.84 |

| Progressive motility (%) | 15 | 77.82 | 3.06 | 83.40 | 54.07 | 94.02 |

| VCL (µm/s) | 15 | 142.36 | 8.04 | 145.26 | 96.34 | 203.44 |

| Parameter | Phase | Fast Cooling (Mean ± SEM) | Moderate Cooling (Mean ± SEM) | Slow Cooling (Mean ± SEM) | Effect | F-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TM (%) | Post Cooling | 84.49 ± 1.77 | 83.62 ± 2.43 | 82.73 ± 2.58 | Phase | 1008.55 | <0.001 |

| Cooling Rate | 5.86 | 0.004 | |||||

| Post Thaw | 51.87 ± 3.65 | 50.94 ± 3.27 | 45.01 ± 4.15 | Phase: Cooling Rate | 3.82 | 0.027 | |

| PM (%) | Post Cooling | 71.28 ± 3.37 | 70.1 ± 4.15 | 69.84 ± 4.04 | Phase | 1094.66 | <0.001 |

| Cooling Rate | 1.64 | 0.201 | |||||

| Post Thaw | 30.99 ± 3.3 | 29.47 ± 3.75 | 26.9 ± 3.91 | Phase: Cooling Rate | 1.16 | 0.320 | |

| FM (%) | Post Cooling | 31.34 ± 3.38 | 32.42 ± 3.64 | 32.77 ± 3.62 | Phase | 1167.45 | <0.001 |

| Cooling Rate | 0.18 | 0.834 | |||||

| Post Thaw | 7.98 ± 1.31 | 7.93 ± 1.25 | 7.47 ± 1.5 | Phase: Cooling Rate | 0.90 | 0.411 | |

| CM (%) | Post Cooling | 7.51 ± 0.87 | 7.3 ± 0.88 | 6.67 ± 0.87 | Phase | 948.67 | <0.001 |

| Cooling Rate | 3.02 | 0.055 | |||||

| Post Thaw | 1.67 ± 0.42 | 1.24 ± 0.18 | 1.18 ± 0.23 | Phase: Cooling Rate | 1.53 | 0.224 | |

| VCL (µm/s) | Post Cooling | 125.98 ± 6.33 | 125.32 ± 6.61 | 123.81 ± 6.87 | Phase | 1051.83 | <0.001 |

| Cooling Rate | 0.20 | 0.820 | |||||

| Post Thaw | 68.23 ± 4.53 | 66.89 ± 3.12 | 67.47 ± 3.99 | Phase: Cooling Rate | 0.09 | 0.911 |

| Parameter | Fast Cooling (Mean ± SEM) | Moderate Cooling (Mean ± SEM) | Slow Cooling (Mean ± SEM) | F-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Viability (%) | 61.67 ± 2.01 | 64.68 ± 2.02 | 65.59 ± 2.15 | 2.76 | 0.08 |

| Acrosome Disrupted (%) | 1.16 ± 0.19 | 1.22 ± 0.25 | 1.17 ± 0.14 | 0.76 | 0.48 |

| Acrosome Intact (%) | 26.34 ± 2.01 | 26.15 ± 1.98 | 24.85 ± 1.97 | 0.32 | 0.73 |

| MMP | 0.96 ± 0.19 | 0.91 ± 0.16 | 1.18 ± 0.28 | 0.83 | 0.45 |

| Viable ROS− (%) | 16.5 ± 2.06 | 17.71 ± 1.96 | 16.09 ± 1.65 | 0.34 | 0.71 |

| Viable ROS+ (%) | 20.5 ± 2.47 | 18.53 ± 1.94 | 18.83 ± 1.77 | 0.68 | 0.52 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bitton, A.; Frishling, A.; Kalo, D.; Roth, Z.; Arav, A. The Impact of Precisely Controlled Pre-Freeze Cooling Rates on Post-Thaw Stallion Sperm. Animals 2026, 16, 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010021

Bitton A, Frishling A, Kalo D, Roth Z, Arav A. The Impact of Precisely Controlled Pre-Freeze Cooling Rates on Post-Thaw Stallion Sperm. Animals. 2026; 16(1):21. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010021

Chicago/Turabian StyleBitton, Aviv, Amos Frishling, Dorit Kalo, Zvi Roth, and Amir Arav. 2026. "The Impact of Precisely Controlled Pre-Freeze Cooling Rates on Post-Thaw Stallion Sperm" Animals 16, no. 1: 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010021

APA StyleBitton, A., Frishling, A., Kalo, D., Roth, Z., & Arav, A. (2026). The Impact of Precisely Controlled Pre-Freeze Cooling Rates on Post-Thaw Stallion Sperm. Animals, 16(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010021