Comparative RNA-Seq Analysis of Differentially Expressed Genes in the Testis and Ovary of Mudskipper, Boleophthalmus pectinirostris

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Sampling

2.2. Gonadal Histology

2.3. RNA-Seq

2.4. In Silico Analysis of Target Genes

2.5. Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR)

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

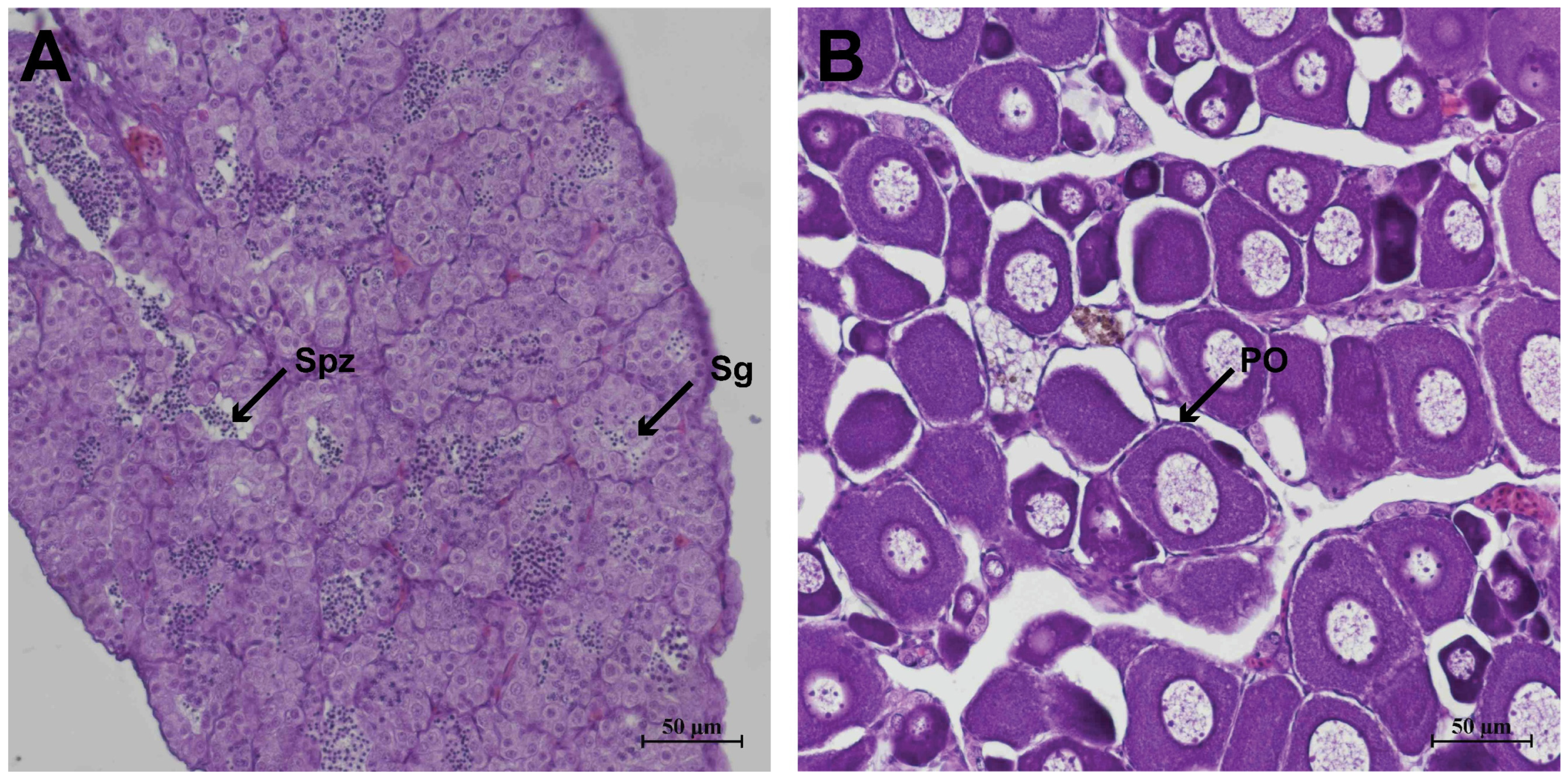

3.1. Histological Characteristics of the Gonads

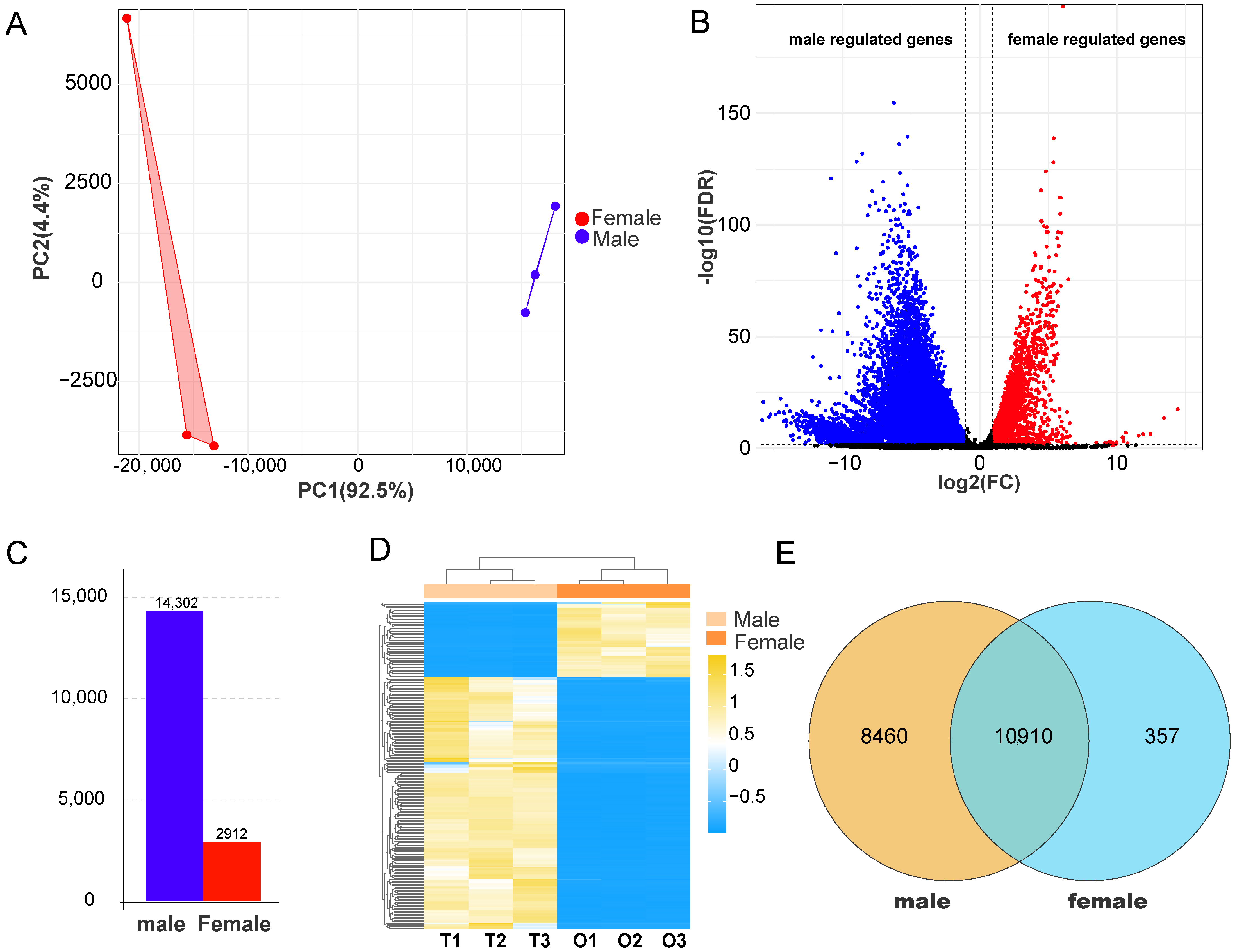

3.2. Transcriptome Data Quality and Identification of DEGs

3.3. Functional Enrichment Analysis of DEGs

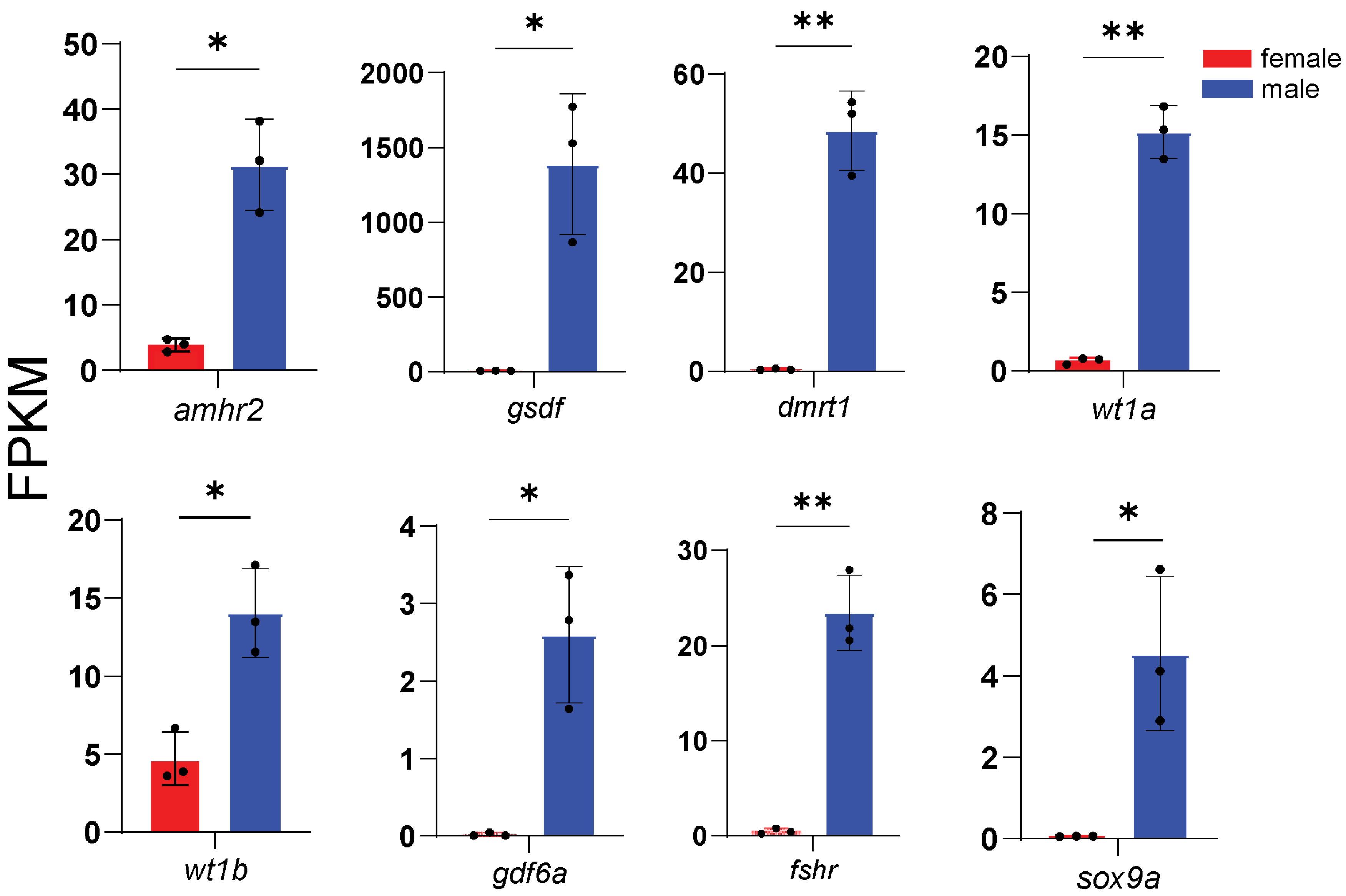

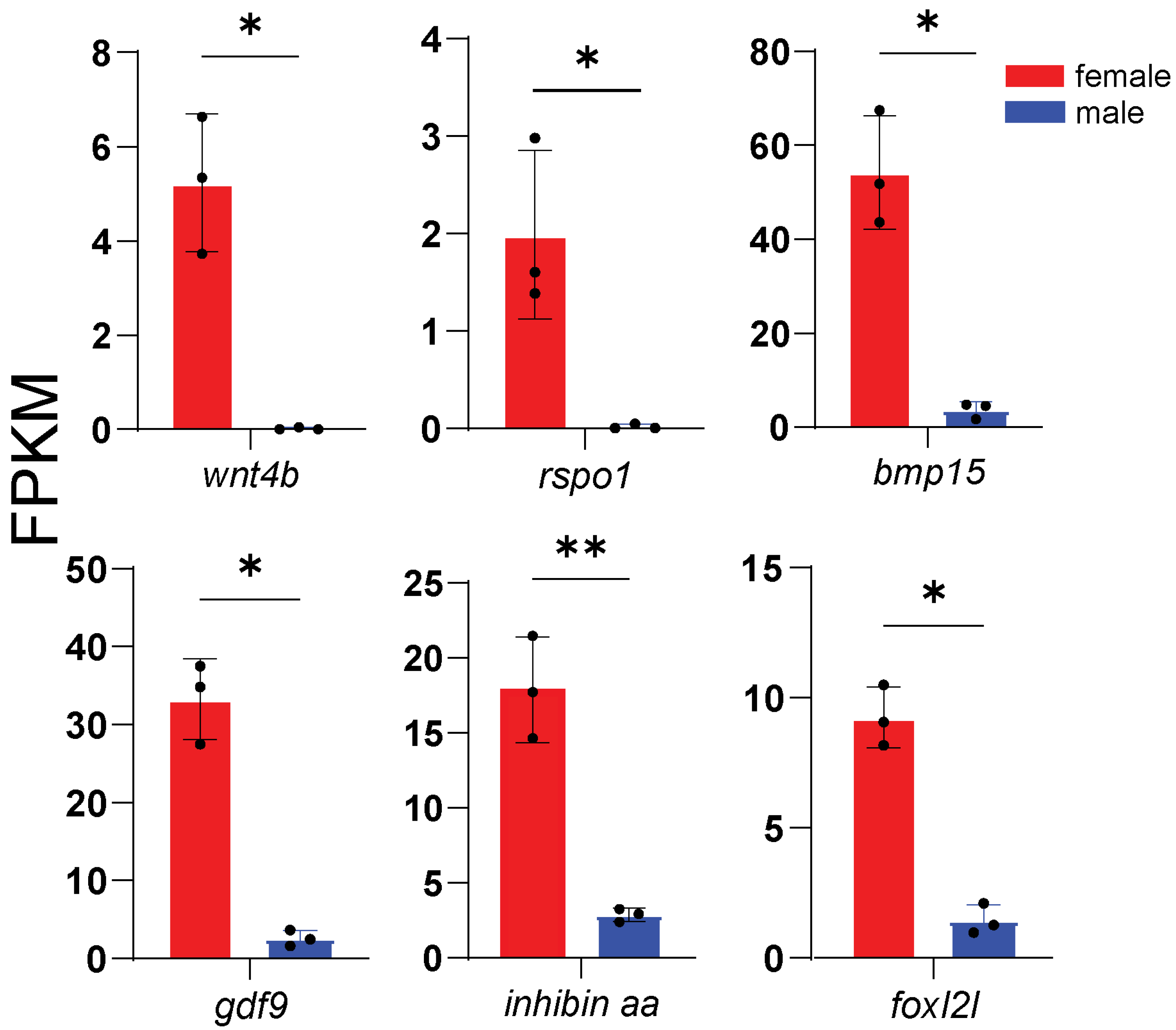

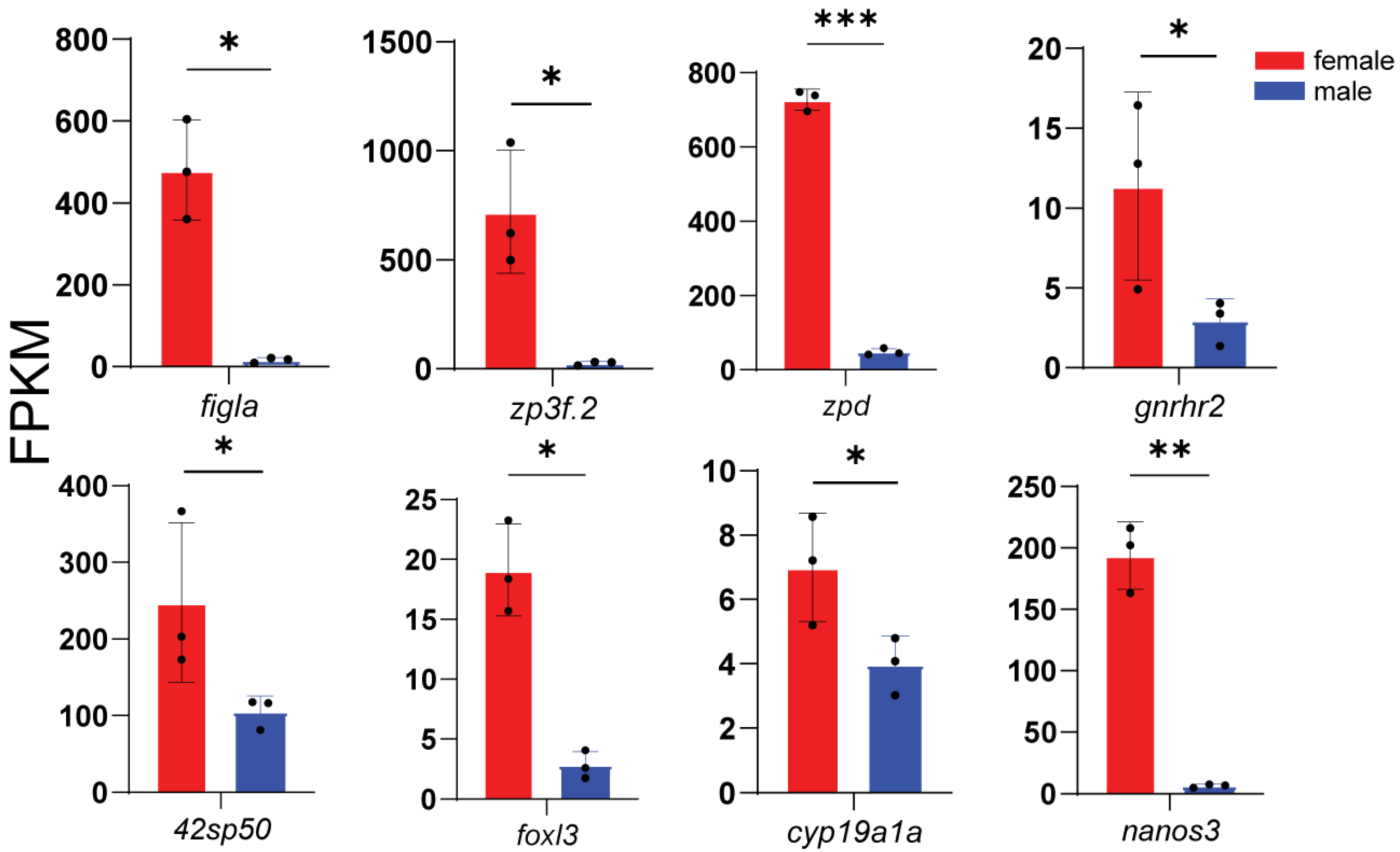

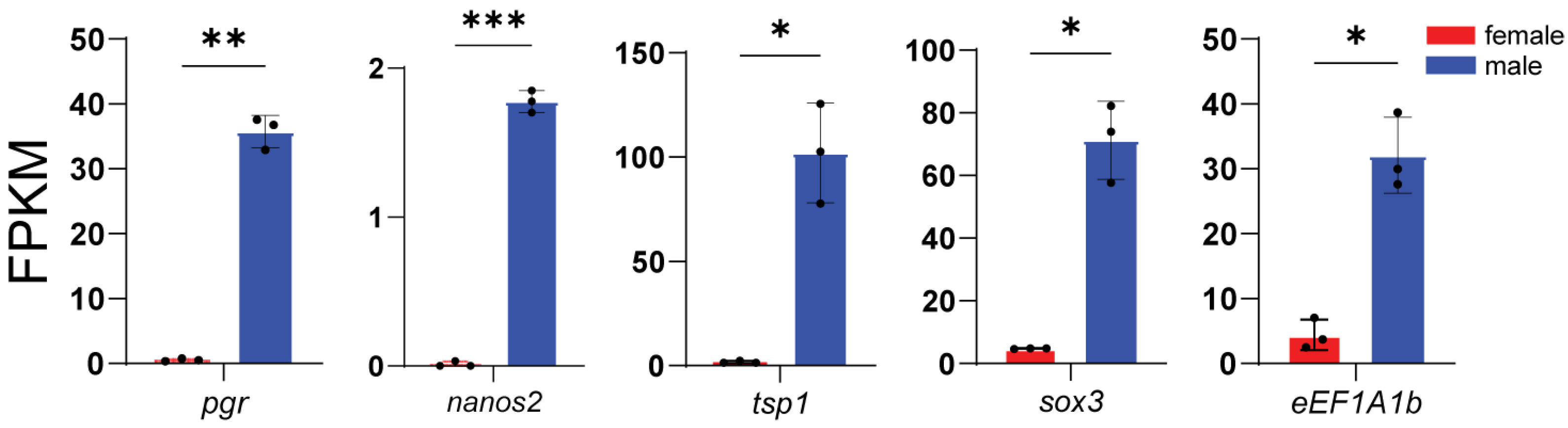

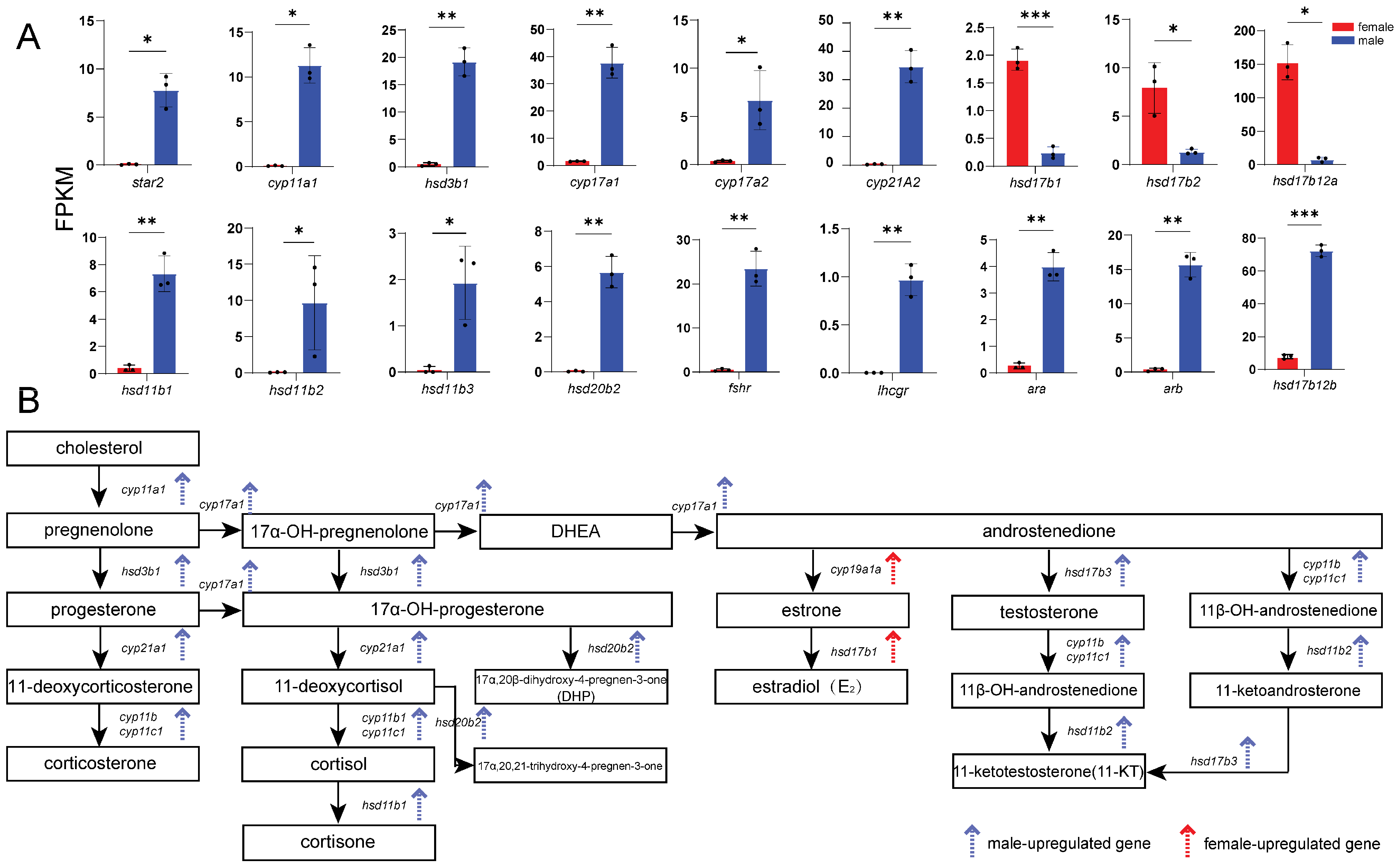

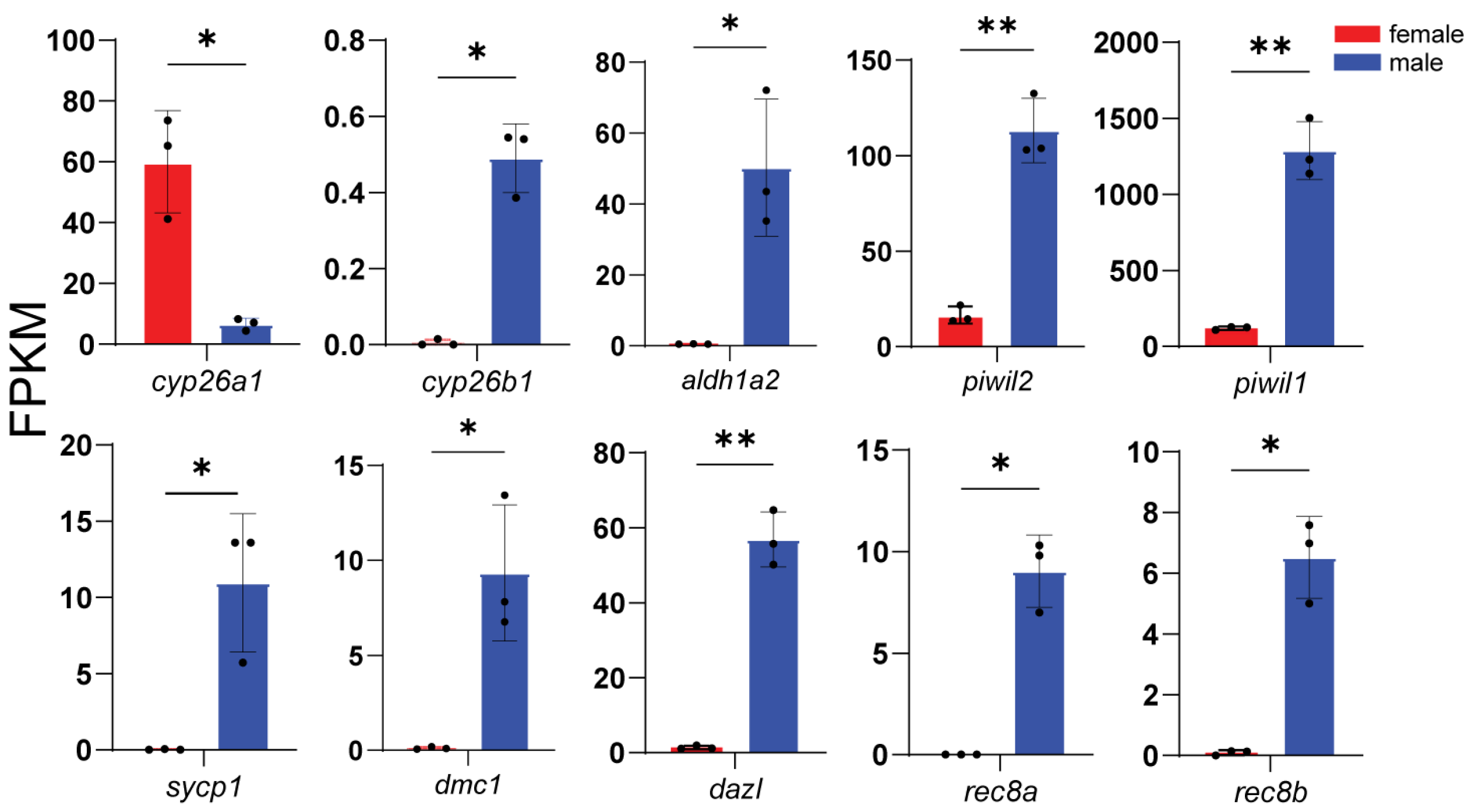

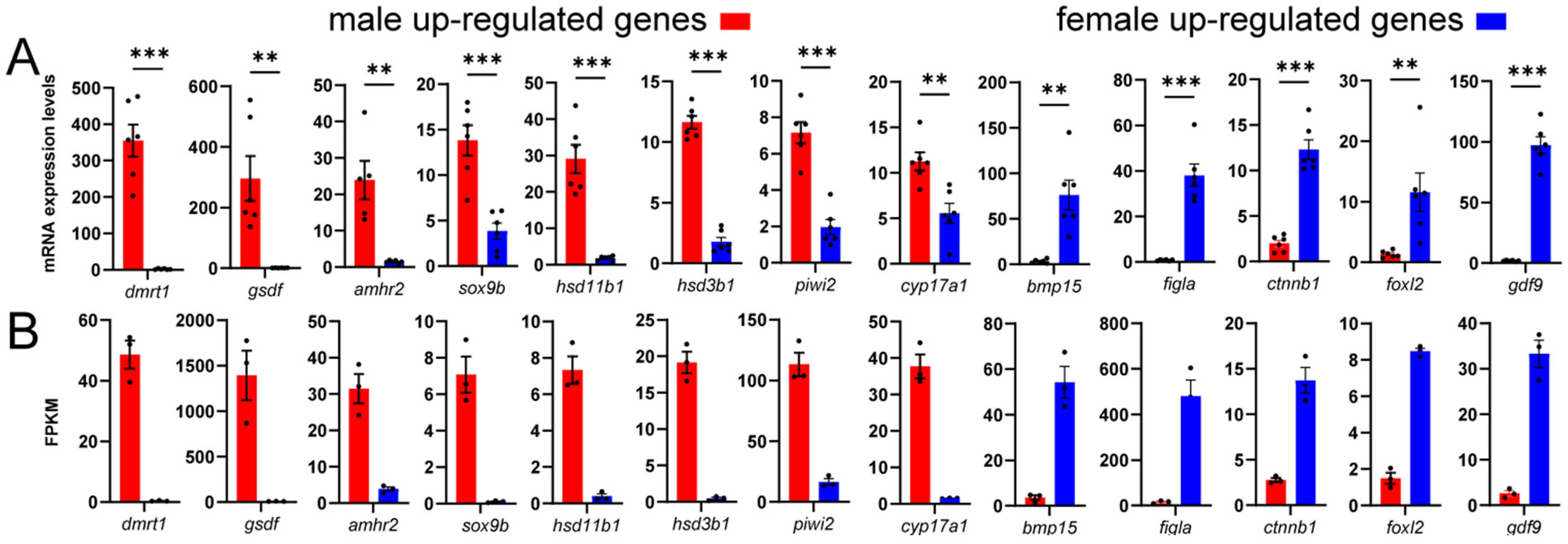

3.4. Expression of Representative DEGs

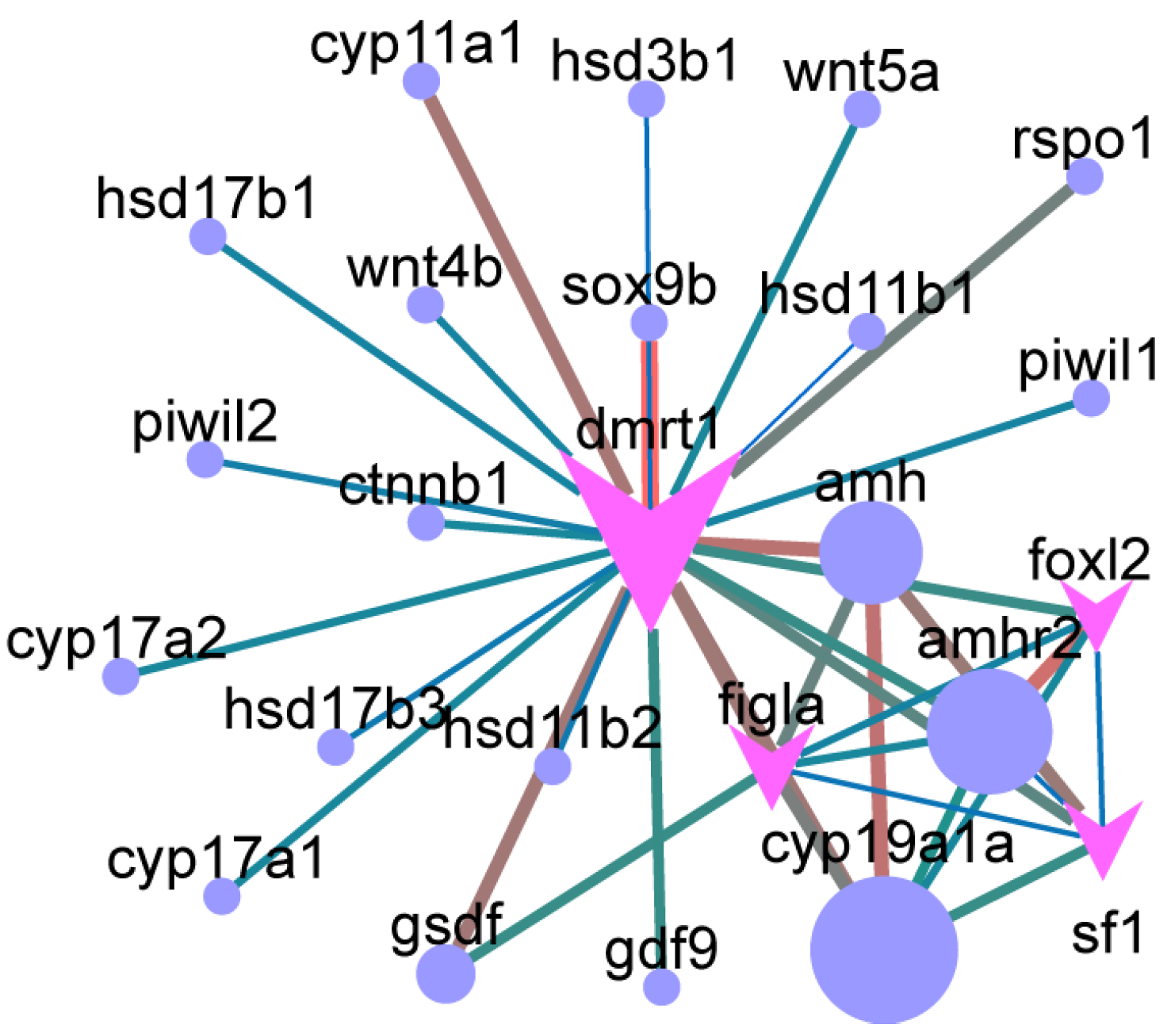

3.5. Core Sex-Related Genes and Regulatory Networks

3.6. Key Gene Family in Silico Analysis

3.7. Transcriptome Data Validation

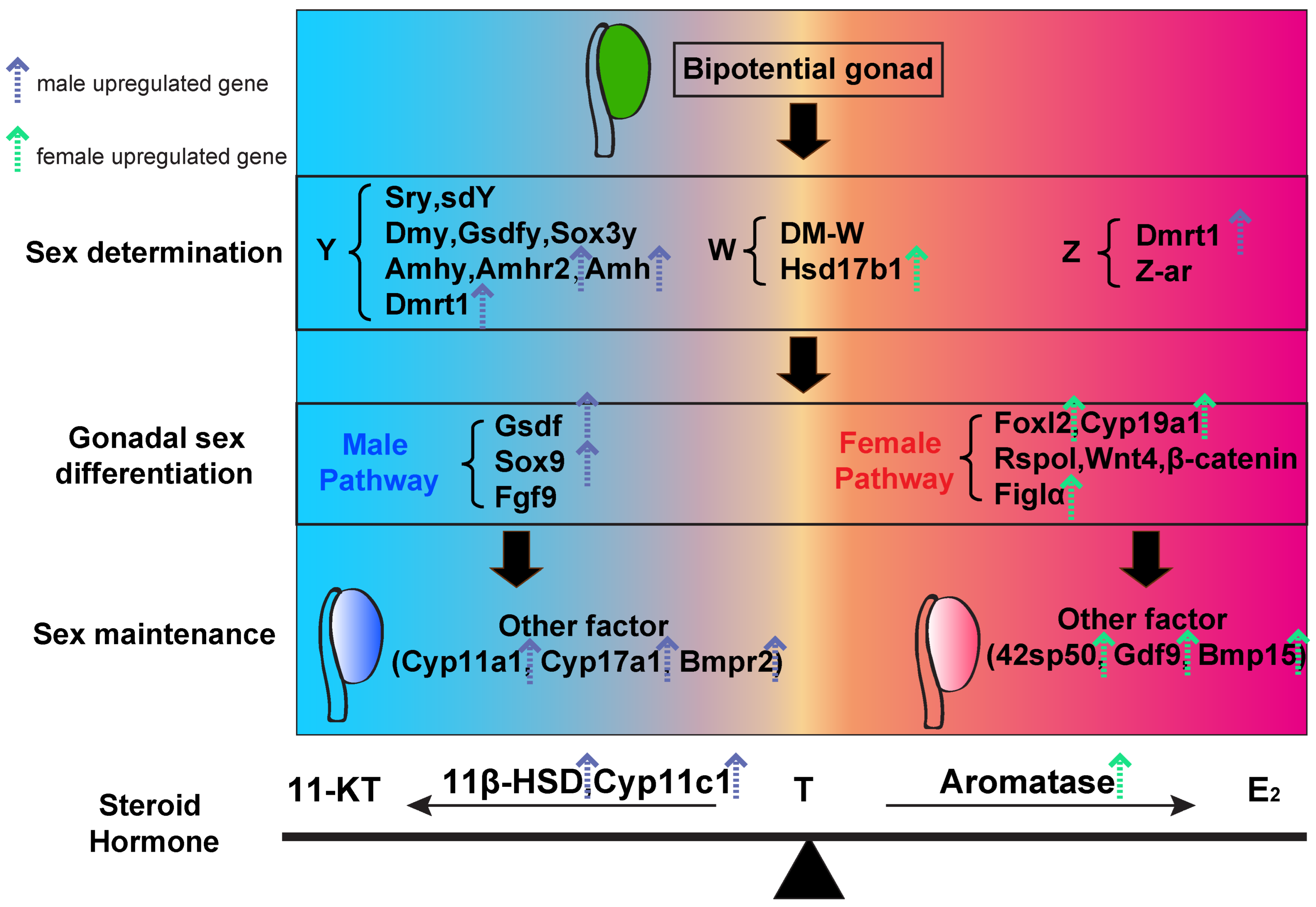

4. Discussion

4.1. Two Alternatively Spliced Transcripts of amh Are Expressed in Both Testes and Ovaries

4.2. Enrichment of Sex-Determining and Differentiation Genes

4.3. Differentially Expressed Genes Involved in Gametogenesis and Steroidogenesis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Capel, B. Vertebrate sex determination: Evolutionary plasticity of a fundamental switch. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2017, 18, 675–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagahama, Y.; Chakraborty, T.; Paul-Prasanth, B.; Ohta, K.; Nakamura, M. Sex determination, gonadal sex differentiation, and plasticity in vertebrate species. Physiol. Rev. 2021, 101, 1237–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Mei, J.; Ge, C.; Liu, X.; Gui, J. Sex determination mechanisms and sex control approaches in aquaculture animals. Sci. China Life Sci. 2022, 65, 1091–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Z.; Younas, L.; Zhou, Q. Evolution and regulation of animal sex chromosomes. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2024, 26, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, B.; Hu, W. Research progress on sex control breeding of fish. Acta Math. Sin. 2022, 44, 397–405. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Gui, J. Diverse and variable sex determination mechanisms in vertebrates. Sci. China Life Sci. 2018, 61, 1503–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herpin, A.; Schartl, M. Plasticity of gene-regulatory networks controlling sex determination: Of masters, slaves, usual suspects, newcomers, and usurpators. EMBO Rep. 2015, 16, 1260–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokarz, J.; Moeller, G.; de Angelis, M.H.; Adamski, J. Steroids in teleost fishes: A functional point of view. Steroids 2015, 103, 123–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Li, Z.; Ding, M.; Yao, T.; Yang, S.; Zhang, X.; Miao, C.; Du, W.; Shi, Q.; Li, S.; et al. Two duplicated gsdf homeologs cooperatively regulate male differentiation by inhibiting cyp19a1a transcription in a hexaploid fish. PLoS Genet. 2022, 18, e1010288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Jeng, S.; Lei, Z.; Yueh, W.; Dufour, S.; Wu, G.; Chang, C. Involvement of transforming growth factor beta family genes in gonadal differentiation in Japanese eel, Anguilla japonica, according to sex-related gene expressions. Cells 2021, 10, 3007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Han, C.; Huang, J.; Li, M.; Yang, J.; Li, G.; Lin, H.; Li, S.; Zhang, Y. Genome-wide identification, evolution and expression of TGF-β signaling pathway members in mandarin fish (Siniperca chuatsi). Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 253, 126949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, J.; Cui, T.; Xia, W.; Luo, Q.; Fei, S.; Zhu, X.; Chen, K.; Zhao, J.; Ou, M. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and transcriptome analysis reveal male heterogametic sex-determining regions and candidate genes in northern snakeheads (Channa argus). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Qiu, X.; Kong, D.; Zhou, X.; Guo, Z.; Gao, C.; Ma, S.; Hao, W.; Jiang, Z.; Liu, S. Comparative RNA-Seq analysis of differentially expressed genes in the testis and ovary of Takifugu rubripes. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. D Genom. Proteom. 2017, 22, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Cui, X.; Shen, X.; Wang, L.; Jiang, L.; Liu, H.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Q.; Jiang, C. De novo transcriptome analysis and differentially expressed genes in the ovary and testis of the Japanese mantis shrimp Oratosquilla oratoria by RNA-Seq. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. D Genom. Proteom. 2018, 26, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.; Ao, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhao, L.; Ma, S.; Jiang, Y. Comparison of differential expression genes in ovaries and testes of Pearlscale angelfish Centropyge vrolikii based on RNA-Seq analysis. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 47, 1565–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, F.; Gu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, K.; Shi, L.; Sun, J.; Zhang, Z.; Luo, J. Transcriptome analysis provides insights into differentially expressed long noncoding RNAs between the testis and ovary in golden pompano (Trachinotus blochii). Aquacult. Rep. 2022, 22, 100971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Cai, R.; Shi, W.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Z.; Xie, F.; Chen, Y.; Hong, Q. Comparative transcriptome analysis of ovaries and testes reveals sex-biased genes and pathways in zebrafish. Gene 2024, 901, 148176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Wen, Z.; Amenyogbe, E.; Jin, J.; Lu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Huang, J. Comparative Transcriptome Analysis of Sexual Differentiation in Male and Female Gonads of Nao-Zhou Stock Large Yellow Croaker (Larimichthys crocea). Animals 2024, 14, 3261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Huang, Z.; Li, Q.; Li, W.; Han, C.; Yang, Y.; Lin, H.; Wu, Q.; Zhou, Y. De novo assembly, characterization, and comparative transcriptome analysis of mature male and female gonads of rabbitfish (Siganus oramin) (Bloch and Schneider, 1801). Animals 2024, 14, 1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, D.; Xia, S.; Xing, T.; Gao, Y.; Liu, J. Comparative transcriptomic analysis of ovary and testis reveals sex-related genes in roughskin sculpin Trachidermus fasciatus. J. Oceanol. Limnol. 2024, 42, 1673–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.-l.; Liu, P.; Jia, F.-l.; Li, J.; Gao, B.-Q. De novo transcriptome analysis of Portunus trituberculatus ovary and testis by RNA-Seq: Identification of genes involved in gonadal development. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0128659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.; Yoon, B.-H.; Kim, W.-J.; Kim, D.-W.; Hurwood, D.A.; Lyons, R.E.; Salin, K.R.; Kim, H.-S.; Baek, I.; Chand, V. Optimizing hybrid de novo transcriptome assembly and extending genomic resources for giant freshwater prawns (Macrobrachium rosenbergii): The identification of genes and markers associated with reproduction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, H.; Hong, W.; Chen, S. A progestin regulates the prostaglandin pathway in the neuroendocrine system in female mudskipper Boleophthalmus pectinirostris. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2023, 231, 106300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, H.; Yang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Qiu, H.; You, X.; Chen, S.; Hong, W. Expressions of melanopsins in telencephalon imply their function in synchronizing semilunar spawning rhythm in the mudskipper Boleophthalmus pectinirostris. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2022, 315, 113926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, C.; Huang, Y.; Li, R.; Xu, P.; You, X.; Lv, Y.; Ruan, Z.; Chen, J.; Xu, J.; Shi, Q. Genomics comparisons of three chromosome-level mudskipper genome assemblies reveal molecular clues for water-to-land evolution and adaptation. J. Adv. Res. 2024, 58, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, W.; Chen, S.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Q. Reproductive ecology of the mudskipper Bolephthalmus pectinirostris. Acta Oceanolog. Sin. 2007, 26, 72–81. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz, R.W.; de Franca, L.R.; Lareyre, J.J.; Legac, F.; Chiarini-Garcia, H.; Nobrega, R.H.; Miura, T. Spermatogenesis in fish. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2010, 165, 390–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubzens, E.; Young, G.; Bobe, J.; Cerdà, J. Oogenesis in teleosts: How fish eggs are formed. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2010, 165, 367–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Q.; Feron, R.; Yano, A.; Guyomard, R.; Jouanno, E.; Vigouroux, E.; Wen, M.; Busnel, J.-M.; Bobe, J.; Concordet, J.-P. Identification of the master sex determining gene in Northern pike (Esox lucius) reveals restricted sex chromosome differentiation. PLoS Genet. 2019, 15, e1008013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Wang, D.; Liu, X. Amh/Amhr2 homologs: The predominant recurrent sex determining genes in teleosts. Water Biol. Secur. 2025, 100492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Yue, Y.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, Z.; Shan, H.; He, H.; Ge, W. Disrupting Amh and androgen signaling reveals their distinct roles in zebrafish gonadal differentiation and gametogenesis. Commun. Biol. 2025, 8, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitano, J.; Ansai, S.; Takehana, Y.; Yamamoto, Y. Diversity and convergence of sex-determination mechanisms in teleost fish. Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci. 2024, 12, 233–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Xie, Y.; Sun, M.; Li, X.; Fitzpatrick, C.K.; Vaux, F.; O’Malley, K.G.; Zhang, Q.; Qi, J.; He, Y. A duplicated amh is the master sex-determining gene for Sebastes rockfish in the Northwest Pacific. Open Biol. 2021, 11, 210063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, J.; Shi, H.; Zeng, S.; Ye, K.; Jiang, D.; Zhou, L.; Sun, L.; Tao, W.; et al. A tandem duplicate of anti-Müllerian hormone with a missense SNP on the Y chromosome is essential for male sex determination in Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus. PLoS Genet. 2015, 11, e1005678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feron, R.; Zahm, M.; Cabau, C.; Klopp, C.; Roques, C.; Bouchez, O.; Eché, C.; Valière, S.; Donnadieu, C.; Haffray, P. Characterization of a Y-specific duplication/insertion of the anti-Mullerian hormone type II receptor gene based on a chromosome-scale genome assembly of yellow perch, Perca flavescens. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2020, 20, 531–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Sarida, M.; Hattori, R.S.; Strüssmann, C.A. Coexistence of genotypic and temperature-dependent sex determination in pejerrey Odontesthes bonariensis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e102574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Gong, G.; Li, Z.; Niu, J.; Du, W.-X.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, X.; Lian, Z.; et al. Genomic anatomy of homozygous XX females and YY males reveals early evolutionary trajectory of sex-determining gene and sex chromosomes in Silurus fishes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2024, 41, msae169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Tao, H.; Song, Y.; Li, M.; Yang, H.; Li, J.; Yan, H.; Sheraliev, B.; Tao, W.; Peng, Z.; et al. The origin, evolution, and translocation of sex chromosomes in Silurus catfish mediated by transposons. BMC Biol. 2025, 23, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wan, S.; Ravi, V.; Qin, G.; Jiang, H.; Wang, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, B.; et al. Seadragon genome analysis provides insights into its phenotype and sex determination locus. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabg5196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattori, R.S.; Murai, Y.; Oura, M.; Masuda, S.; Majhi, S.K.; Sakamoto, T.; Fernandino, J.I.; Somoza, G.M.; Yokota, M.; Strüssmann, C.A. A Y-linked anti-Müllerian hormone duplication takes over a critical role in sex determination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. India Sect. 2012, 109, 2955–2959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Du, X.; Ren, F.; Liu, Y.; Gong, G.; Ge, S.; Li, W.; Li, Z.; Zhou, L.; Duan, M.; et al. Anti-Müllerian hormone signalling sustains circadian homeostasis in zebrafish. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 4359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhu, B.; Chen, W.; Ge, W. Anti-Müllerian hormone (Amh/amh) plays dual roles in maintaining gonadal homeostasis and gametogenesis in zebrafish. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2020, 517, 110963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augstenová, B.; Ma, W.-J. Decoding Dmrt1: Insights into vertebrate sex determination and gonadal sex differentiation. J. Evol. Biol. 2025, 38, 811–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webster, K.A.; Schach, U.; Ordaz, A.; Steinfeld, J.S.; Draper, B.W.; Siegfried, K.R. Dmrt1 is necessary for male sexual development in zebrafish. Dev. Biol. 2017, 422, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Song, W.; Zhang, Z.; Ge, W. Disruption of dmrt1 rescues the all-male phenotype of the cyp19a1a mutant in zebrafish–a novel insight into the roles of aromatase/estrogens in gonadal differentiation and early folliculogenesis. Development 2020, 147, dev182758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, S.; Dai, S.; Zhou, X.; Wei, X.; Chen, P.; He, Y.; Kocher, T.D.; Wang, D.; Li, M. Dmrt1 is the only male pathway gene tested indispensable for sex determination and functional testis development in tilapia. PLoS Genet. 2024, 20, e1011210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Bian, C.; Jiao, K.; Zhang, L.; Huang, Y.; Yang, W.; Li, Y.; Shi, G.; Huang, Y. Allelic variation and duplication of the dmrt1 were associated with sex chromosome turnover in three representative Scatophagidae fish species. Commun. Biol. 2025, 8, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawatari, E.; Shikina, S.; Takeuchi, T.; Yoshizaki, G. A novel transforming growth factor-β superfamily member expressed in gonadal somatic cells enhances primordial germ cell and spermatogonial proliferation in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Dev. Biol. 2007, 301, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imai, T.; Saino, K.; Matsuda, M. Mutation of Gonadal soma-derived factor induces medaka XY gonads to undergo ovarian development. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015, 467, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Desvignes, T.; Bremiller, R.; Wilson, C.; Dillon, D.; High, S.; Draper, B.; Buck, C.L.; Postlethwait, J. Gonadal soma controls ovarian follicle proliferation through Gsdf in zebrafish. Dev. Dyn. 2017, 246, 925–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, B.L.; Buonaccorsi, V.P. Genomic characterization of sex-identification markers in Sebastes carnatus and Sebastes chrysomelas rockfishes. Mol. Ecol. 2016, 25, 2165–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, R.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Yu, Z.; Li, X.-Y.; Tong, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, L.; Gui, J. Functional divergence of multiple duplicated Foxl2 homeologs and alleles in a recurrent polyploid fish. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 1995–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamoto, M.; Matsuda, M.; Wang, D.; Nagahama, Y.; Shibata, N. Molecular cloning and analysis of gonadal expression of Foxl2 in the medaka, Oryzias latipes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006, 344, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, K.; Zhai, Y.; Qin, M.; Zhao, C.; Ai, N.; He, J.; Ge, W. Genetic evidence for differential functions of figla and nobox in zebrafish ovarian differentiation and folliculogenesis. Commun. Biol. 2023, 6, 1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crespo, D.; Fjelldal, P.G.; Hansen, T.J.; Kjærner-Semb, E.; Skaftnesmo, K.O.; Thorsen, A.; Norberg, B.; Edvardsen, R.B.; Andersson, E.; Schulz, R.W. Loss of bmp15 function in the seasonal spawner Atlantic salmon results in ovulatory failure. FASEB J. 2024, 38, e23837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, M.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, J.; Zhang, Q. Growth differentiation factor 9 (gdf9) and bone morphogenetic protein 15 (bmp15) are potential intraovarian regulators of steroidogenesis in Japanese flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus). Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2020, 297, 113547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halm, S.; Ibáñez, A.J.; Tyler, C.R.; Prat, F. Molecular characterisation of growth differentiation factor 9 (gdf9) and bone morphogenetic protein 15 (bmp15) and their patterns of gene expression during the ovarian reproductive cycle in the European sea bass. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2008, 291, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Ge, W. Growth differentiation factor 9 and its spatiotemporal expression and regulation in the zebrafish ovary. Biol. Reprod. 2007, 76, 294–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, D.; Houlgatte, R.; Fostier, A.; Guiguen, Y. Large-scale temporal gene expression profiling during gonadal differentiation and early gametogenesis in rainbow trout. Biol. Reprod. 2005, 73, 959–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Sun, S.; Charkraborty, T.; Wu, L.; Sun, L.; Wei, J.; Nagahama, Y.; Wang, D.; Zhou, L. Figla favors ovarian differentiation by antagonizing spermatogenesis in a teleosts, Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0123900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curzon, A.Y.; Shirak, A.; Benet-Perlberg, A.; Naor, A.; Low-Tanne, S.I.; Sharkawi, H.; Ron, M.; Seroussi, E. Absence of figla-like gene is concordant with femaleness in cichlids harboring the LG1 sex-determination system. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Jiao, S.; He, M.; Li, W.; Wang, H.; Ye, D.; Zhu, Z.; Sun, Y. An oocyte and yolk syncytial layer-derived Nanog-cyp11a1-pregnenolone axis promotes extraembryonic development. Sci. Bull. 2025, 70, 4150–4155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, G.; Shu, T.; Yu, G.; Tang, H.; Shi, C.; Jia, J.; Lou, Q.; Dai, X.; Jin, X.; He, J.; et al. Augmentation of progestin signaling rescues testis organization and spermatogenesis in zebrafish with the depletion of androgen signaling. eLife 2022, 11, e66118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wu, Y.; Du, Y.; Ye, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, D.; Zhou, L. Dual cyp17a1/a2 knockout unveils paralog-specific steroid pathways in fish reproduction. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 1, 144772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Wu, L.; Yang, L.; Song, L.; Cai, J.; Luo, F.; Wei, J.; Zhou, L.; Wang, D. Nuclear progestin receptor (Pgr) knockouts resulted in subfertility in male tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2018, 182, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Guo, W.; Gao, Y.; Tang, R.; Li, D. Molecular cloning and characterization of amh and dax1 genes and their expression during sex inversion in rice-field eel Monopterus albus. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 16667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwai, T.; Yoshii, A.; Yokota, T.; Sakai, C.; Hori, H.; Kanamori, A.; Yamashita, M. Structural components of the synaptonemal complex, SYCP1 and SYCP3, in the medaka fish Oryzias latipes. Exp. Cell Res. 2006, 312, 2528–2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Zhang, H.; Wang, F.; Zhang, W.; Peng, G. nr0b1 (DAX1) mutation in zebrafish causes female-to-male sex reversal through abnormal gonadal proliferation and differentiation. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2016, 433, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaya, I.; Yilmaz, I.N.; Nour-Kasally, N.; Charboneau, R.E.; Draper, B.W.; Burgess, S.M. Distinct cellular and reproductive consequences of meiotic chromosome synapsis defects in syce2 and sycp1 mutant zebrafish. PLoS Genet. 2025, 21, e1011656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ma, H.; Bian, C.; Tian, C.; Shi, H.; Wu, T.; Deng, S.; Li, G.; Jiang, D. Comparative RNA-Seq Analysis of Differentially Expressed Genes in the Testis and Ovary of Mudskipper, Boleophthalmus pectinirostris. Animals 2026, 16, 150. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010150

Ma H, Bian C, Tian C, Shi H, Wu T, Deng S, Li G, Jiang D. Comparative RNA-Seq Analysis of Differentially Expressed Genes in the Testis and Ovary of Mudskipper, Boleophthalmus pectinirostris. Animals. 2026; 16(1):150. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010150

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, He, Chao Bian, Changxu Tian, Hongjuan Shi, Tianli Wu, Siping Deng, Guangli Li, and Dongneng Jiang. 2026. "Comparative RNA-Seq Analysis of Differentially Expressed Genes in the Testis and Ovary of Mudskipper, Boleophthalmus pectinirostris" Animals 16, no. 1: 150. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010150

APA StyleMa, H., Bian, C., Tian, C., Shi, H., Wu, T., Deng, S., Li, G., & Jiang, D. (2026). Comparative RNA-Seq Analysis of Differentially Expressed Genes in the Testis and Ovary of Mudskipper, Boleophthalmus pectinirostris. Animals, 16(1), 150. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010150