Synergistic Regulation of Bile Acid-Driven Nitrogen Metabolism by Swollenin in Ruminants: A Microbiota-Targeted Strategy to Improve Nitrogen Use Efficiency

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Swollenin Production, Animal Trial Design, and Housing

2.2. Growth Performance and Sample Collection

2.3. DNA Extraction and Metagenomic Sequencing

2.4. Targeted Metabolomics Analysis in Bile Acid Metabolism

2.5. Statistical Analysis and Mapping

3. Results

3.1. Effect of Swollenin on Goat Growth Performance

3.2. Effect of Swollenin on Gut Microbiota Changes in Young Goats

3.3. Effect of Swollenin on Bile Acid-Metabolizing Bacteria in the Gut of Goats

3.4. The Effect of Swollenin on the Abundance of Secondary Bile Acid Metabolism-Related Genes in the Gut of Goats

3.5. The Effect of Swollenin on Intestinal Bile Acid Metabolism in Young Goats

3.6. Impact of Swollenin on Nitrogen Cycling in the Intestine of Young Goats

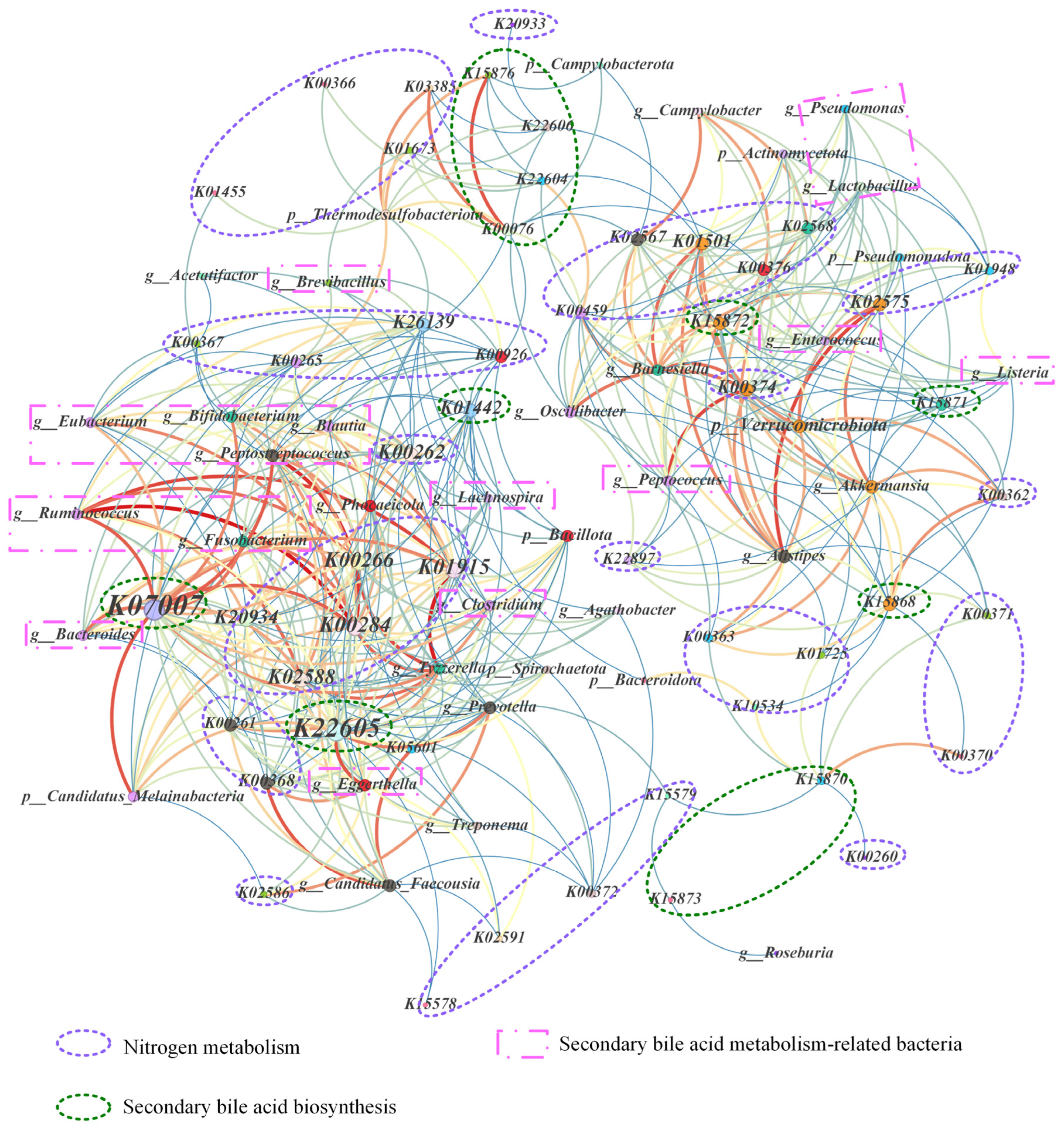

3.7. The Co-Occurrence Network Among Nitrogen Metabolism Pathways, Secondary Bile Acid Metabolism-Related Genes, and Microbial Communities

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BAs | Bile acids | ADFI | Average daily feed intake |

| BSH | Bile salt hydrolase | Swol | Swollenin group |

| CON | Control | BW | Body weight |

| ADG | Average daily gain | GCA | Glycocholic acid |

| DMI | Daily dry matter intake | TCA | Tarocholic acid |

| F/G | Feed conversion ratio | GCDCA | Glycochenodeoxycholic acid |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes | TCDCA | Taurochenodeoxycholic acid |

| KO | KEGG Orthology | CA | Cholic acid |

| FDR | False discovery rate | CDCA | Chenodeoxycholic acid |

| LDA | Linear Discriminant Analysis | DCA | Deoxycholic acid |

| LEfSe | Linear Discriminant Analysis Effect Size | LCA | Lithocholic acid |

| PCoA | Principal Coordinate Analysis | UDCA | Ursodeoxycholic acid |

| NO2− | Nitrite | NO3− | Nitrate |

| NO | Nitric oxide | N2O | Nitrous oxide |

| N2 | Nitrogen | N2H4 | Hydrazine |

| NH3 | Ammonia | R-CN | Nitrile |

| CO2 | Carbon dioxide | bai | Bile acid-induced |

| HSDH | Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase |

References

- Nguyen, H.D.; Moss, A.F.; Yan, F.; Romero-Sanchez, H.; Dao, T.H. Effects of feeding methionine hydroxyl analogue chelated zinc, copper, and manganese on growth performance, nutrient digestibility, mineral excretion, And welfare conditions of broiler chickens: Part 2: Sustainability and Welfare Aspects. Animals 2025, 15, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, W.; Wang, W.; Yu, N.; Liu, P.; Zhao, B.; Zhang, J.; Ren, B. Dual film-controlled model urea improves summer maize yields, N fertilizer use efficiency and reduces greenhouse gas emissions. Soil Tillage Res. 2025, 252, 106565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoekman, S.K. Review of Nitrous Oxide (N2O) Emissions from Motor Vehicles. SAE Int. J. Fuels Lubr. 2020, 13, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Zhang, M.; Ni, Y.; Shen, G. Mitigation Strategies for NH3 and N2O Emissions in Greenhouse Agriculture: Insights into Fertilizer Management and Nitrogen Emission Mechanisms. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2024, 37, 103995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uwizeye, A.; De Boer, I.J.M.; Opio, C.I.; Schulte, R.P.O.; Falcucci, A.; Tempio, G.; Teillard, F.; Casu, F.; Rulli, M.; Galloway, J.N.; et al. Nitrogen emissions along global livestock supply chains. Nat. Food 2020, 1, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouwman, L.; Goldewijk, K.K.; Van Der Hoek, K.W.; Beusen, A.H.W.; Van Vuuren, D.P.; Willems, J.; Rufino, M.C.; Stehfest, E. Exploring global changes in nitrogen and phosphorus cycles in agriculture induced by livestock production over the 1900–2050 period. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 110, 20882–20887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Terranova, M.; Kreuzer, M.; Marquardt, S.; Eggerschwiler, L.; Schwarm, A. Supplementation of Pelleted Hazel (Corylus avellana) Leaves Decreases Methane and Urinary Nitrogen Emissions by Sheep at Unchanged Forage Intake. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 5427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Wang, S.X.; Ran, L.M.; Pleim, J.E.; Cooter, E.; Bash, J.O.; Benson, V.; Hao, J.M. Estimating NH3 emissions from agricultural fertilizer application in China using the bi-directional CMAQ model coupled to an agro-ecosystem model. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2015, 15, 6637–6649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, C.K.; Kristensen, N.B. Nitrogen recycling through the gut and the nitrogen economy of ruminants: An asynchronous symbiosis. J. Anim. Sci. 2007, 86, e293–e305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leduc, M.; Gervais, R.; Chouinard, P. Nitrogen efficiency in cows fed red clover- or alfalfa-silage-based diets differing in rumen-degradable protein supply. Anim.-Open Space 2023, 2, 100050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimal, B.; Collins, S.L.; Tanes, C.E.; Rocha, E.R.; Granda, M.A.; Solanki, S.; Hoque, N.J.; Gentry, E.C.; Koo, I.; Reilly, E.R.; et al. Bile salt hydrolase catalyses formation of amine-conjugated bile acids. Nature 2024, 626, 859–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Yang, S.; Tang, C.; Li, D.; Kan, Y.; Yao, L. New insights into microbial bile salt hydrolases: From physiological roles to potential applications. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1513541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saloheimo, M.; Paloheimo, M.; Hakola, S.; Pere, J.; Swanson, B.; Nyyssönen, E.; Bhatia, A.; Ward, M.; Penttilä, M. Swollenin, a Trichoderma reesei protein with sequence similarity to the plant expansins, exhibits disruption activity on cellulosic materials. Eur. J. Biochem. 2002, 269, 4202–4211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Qu, M.; Liu, C.; Xu, L.; Pan, K.; OuYang, K.; Song, X.; Li, Y.; Liang, H.; Chen, Z.; et al. Effects of recombinant swollenin on the enzymatic hydrolysis, rumen fermentation, and rumen microbiota during in vitro incubation of agricultural straws. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 122, 348–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Lin, Y.; Wang, R.; Sun, M.; Wang, Y.; Lin, Y.; Yang, F.; Ni, K. Microbiome dynamics and metabolic regulation in rumen fibre degradation: Insights into lignocellulose breakdown and rumen fermentation strategies. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 518, 164830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahlström, A.; Sayin, S.I.; Marschall, H.; Bäckhed, F. Intestinal Crosstalk between Bile Acids and Microbiota and Its Impact on Host Metabolism. Cell Metab. 2016, 24, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Sun, Y.; Zhong, X.; Zhu, J.; Yang, S.; Gu, Y.; Yu, X.; Lu, Y.; Lu, Z.; Sun, X.; et al. Dietary crude protein and protein solubility manipulation enhances intestinal nitrogen absorption and mitigates reactive nitrogen emissions through gut microbiota and metabolome reprogramming in sheep. Anim. Nutr. 2024, 18, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Bibber-Krueger, C.L.; Axman, J.E.; Gonzalez, J.M.; Vahl, C.I.; Drouillard, J.S. Effects of yeast combined with chromium propionate on growth performance and carcass quality of finishing steers1. J. Anim. Sci. 2016, 94, 3003–3011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abid, K.; Jabri, J.; Ammar, H.; Said, S.B.; Yaich, H.; Malek, A.; Rekhis, J.; López, S.; Kamoun, M. Effect of treating olive cake with fibrolytic enzymes on feed intake, digestibility and performance in growing lambs. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2020, 261, 114405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Tan, Z.; He, Z. Dietary inclusion of exogenous fibrolytic enzyme to enhance fibrous feed utilization by goats and cattle in southern China. In Exogenous Enzymes as Feed Additives in Ruminants; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 151–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Z.; Chen, Y.; Wang, C.; Yu, H.; Zuo, F.; Huang, W. Probiotic–Enzyme synergy regulates fermentation of distiller’s grains by modifying microbiome structures and symbiotic relationships. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 5363–5375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, H.; Zou, H.; Sun, T.; Li, M.; Zhai, J.; He, Q.; Gu, L.; Tang, W.Z. Effects of acid/alkali pretreatments on lignocellulosic biomass mono-digestion and its co-digestion with waste activated sludge. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 277, 123998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwalm, N.D.; Groisman, E.A. Navigating the Gut Buffet: Control of Polysaccharide Utilization in Bacteroides spp. Trends Microbiol. 2017, 25, 1005–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marion, S.; Studer, N.; Desharnais, L.; Menin, L.; Escrig, S.; Meibom, A.; Hapfelmeier, S.; Bernier-Latmani, R. In vitro and in vivo characterization of Clostridium scindens bile acid transformations. Gut Microbes 2018, 10, 481–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morowitz, M.J.; Carlisle, E.M.; Alverdy, J.C. Contributions of intestinal bacteria to nutrition and metabolism in the critically ill. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2011, 91, 771–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Xu, H.; Liu, Y.; Li, F.; Song, X.; Wang, Z.; Sand, W. Role of GAC-MnO2 catalyst for triggering the extracellular electron transfer and boosting CH4 production in syntrophic methanogenesis. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 383, 123211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, S.; Zhang, M.; Liu, J.; Zhu, W. Characterising the bacterial microbiota across the gastrointestinal tracts of dairy cattle: Membership and potential function. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 16116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costello, E.K.; Lauber, C.L.; Hamady, M.; Fierer, N.; Gordon, J.I.; Knight, R. Bacterial community variation in human body habitats across space and time. Science 2009, 326, 1694–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, N.; Whon, T.W.; Bae, J. Proteobacteria: Microbial signature of dysbiosis in gut microbiota. Trends Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 496–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, J.; Diao, J.; Jia, S.; Feng, P.; Yu, P.; Cheng, G. Anti-inflammatory, cardioprotective effect of gypenoside against isoproterenol-induced cardiac remodeling in rats via alteration of inflammation and gut microbiota. Inflammopharmacology 2023, 31, 2731–2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everard, A.; Belzer, C.; Geurts, L.; Ouwerkerk, J.P.; Druart, C.; Bindels, L.B.; Guiot, Y.; Derrien, M.; Muccioli, G.G.; Delzenne, N.M.; et al. Cross-talk between Akkermansia muciniphila and intestinal epithelium controls diet-induced obesity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 9066–9071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, Z.; Li, Q.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Han, C.; Wang, X.; Zhao, X.; Shi, G. Selenium enhanced nitrogen accumulation in legumes in soil with rhizobia bacteria. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 380, 134960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Li, S.; Zhang, J.; Wu, F.; Li, X.; Wu, D.; Zhang, M.; Ou, Z.; Jie, Z.; Yan, Q.; et al. Genome sequencing of 39 Akkermansia muciniphila isolates reveals its population structure, genomic and functional diverisity, and global distribution in mammalian gut microbiotas. BMC Genom. 2017, 18, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Guan, W.; Xiao, B.; He, Q.; Chen, G.; Wu, J.; Zhao, Z.; You, F.; Yang, J.; Xing, Y.; et al. Optimising microbial processes with nano-carbon/selenite materials: An eco-friendly approach for antibiotic resistance mitigation in broiler manure. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 496, 153695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krautkramer, K.A.; Fan, J.; Bäckhed, F. Gut microbial metabolites as multi-kingdom intermediates. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 19, 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullish, B.H.; McDonald, J.A.K.; Pechlivanis, A.; Allegretti, J.R.; Kao, D.; Barker, G.F.; Kapila, D.; Petrof, E.O.; Joyce, S.A.; Gahan, C.G.M.; et al. Microbial bile salt hydrolases mediate the efficacy of faecal microbiota transplant in the treatment of recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection. Gut 2019, 68, 1791–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridlon, J.M.; Hylemon, P.B. Identification and characterization of two bile acid coenzyme A transferases from Clostridium scindens, a bile acid 7α-dehydroxylating intestinal bacterium. J. Lipid Res. 2011, 53, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, S.C.; Devendran, S.; García, C.M.; Mythen, S.M.; Wright, C.L.; Fields, C.J.; Hernandez, A.G.; Cann, I.; Hylemon, P.B.; Ridlon, J.M. Bile acid oxidation by Eggerthella lentastrains C592 and DSM 2243T. Gut Microbes 2018, 9, 523–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, B. Interplay between gut microbiota and bile acids in diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome: A review. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 48, 696–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doden, H.; Sallam, L.A.; Devendran, S.; Ly, L.; Doden, G.; Daniel, S.L.; Alves, J.M.P.; Ridlon, J.M. Metabolism of Oxo-Bile Acids and Characterization of Recombinant 12α-Hydroxysteroid Dehydrogenases from Bile Acid 7α-Dehydroxylating Human Gut Bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 84, e00235–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Aguiar Vallim, T.Q.; Tarling, E.J.; Edwards, P.A. Pleiotropic roles of bile acids in metabolism. Cell Metab. 2013, 17, 657–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Arai, H.; Nakamura, Y.; Fukiya, S.; Wada, M.; Yokota, A. Contribution of the 7β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase from Ruminococcus gnavus N53 to ursodeoxycholic acid formation in the human colon. J. Lipid Res. 2013, 54, 3062–3069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, A.S.; Fischbach, M.A. A biosynthetic pathway for a prominent class of microbiota-derived bile acids. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2015, 11, 685–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, K.; Zhang, H.; Chen, C.; Ho, C.; Kang, M.; Zhu, S.; Xu, J.; Deng, X.; Huang, Q.; Cao, Y. Heptamethoxyflavone alleviates metabolic syndrome in High-Fat Diet-Fed mice by regulating the composition, function, and metabolism of gut microbiota. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 10050–10064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Z.; Huang, C.; Shi, Y.; Wang, R.; Fan, J.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, K.; Li, M.; Ni, Q.; et al. Distinct bile acid profiles in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection reveal metabolic interplay between host, virus and gut microbiome. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 708495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhowmik, S.; Chiu, H.; Jones, D.H.; Chiu, H.; Miller, M.D.; Xu, Q.; Farr, C.L.; Ridlon, J.M.; Wells, J.E.; Elsliger, M.; et al. Structure and functional characterization of a bile acid 7α dehydratase BaiE in secondary bile acid synthesis. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinform. 2015, 84, 316–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, M.J.; Briz, O. Bile-acid-induced cell injury and protection. World J. Gastroenterol. 2009, 15, 1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Li, Q.; Cao, M.; Yan, J.; Zhang, X. Hierarchy-Assembled dual probiotics system ameliorates cholestatic Drug-Induced liver injury via Gut-Liver axis modulation. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, 2200986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alavi, S.; Mitchell, J.D.; Cho, J.Y.; Liu, R.; Macbeth, J.C.; Hsiao, A. Interpersonal gut microbiome variation drives susceptibility and resistance to cholera infection. Cell 2020, 181, 1533–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, L.E.; Hair, A.B.; Soni, K.G.; Yang, H.; Gollins, L.A.; Narvaez-Rivas, M.; Setchell, K.D.R.; Preidis, G.A. Cholestasis impairs gut microbiota development and bile salt hydrolase activity in preterm neonates. Gut Microbes 2023, 15, 2183690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perino, A.; Demagny, H.; Schoonjans, K. A microbial-derived succinylated bile acid to safeguard liver health. Cell 2024, 187, 2687–2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funabashi, M.; Grove, T.L.; Wang, M.; Varma, Y.; McFadden, M.E.; Brown, L.C.; Guo, C.; Higginbottom, S.; Almo, S.C.; Fischbach, M.A. A metabolic pathway for bile acid dehydroxylation by the gut microbiome. Nature 2020, 582, 566–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, R.; Zhan, M.; Yang, L.; Wang, H.; Shen, H.; Huang, S.; Huang, X.; Xu, S.; Zhang, Z.; Li, W.; et al. Deoxycholic acid modulates the progression of gallbladder cancer through N6-methyladenosine-dependent microRNA maturation. Oncogene 2020, 39, 4983–5000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charbonneau, M.R.; Blanton, L.V.; DiGiulio, D.B.; Relman, D.A.; Lebrilla, C.B.; Mills, D.A.; Gordon, J.I. A microbial perspective of human developmental biology. Nature 2016, 535, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.; Liu, X.; Li, J.; Zhang, M.; Pan, L.; Lu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ding, Y. Effects of bile acids on the growth performance, lipid metabolism, non-specific immunity and intestinal microbiota of Pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei). Aquac. Nutr. 2021, 27, 2029–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, S.; Zhao, P.; Huang, L. Dietary bile acids supplementation improves the growth performance with regulation of serum biochemical parameters and intestinal microbiota of growth retarded European eels (Anguilla anguilla) cultured in cement tanks. Isr. J. Aquac.—Bamidgeh 2020, 72, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Yao, Y.; Huang, J.; Sun, Y.; Wu, Q.; Guo, D.; Wang, S. Effect of dietary bile acids supplementation on growth performance, feed utilization, intestinal digestive enzyme activity and fatty acid transporters gene expression in juvenile leopard coral grouper (Plectropomus leopardus). Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1171344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guérin, N.; Seyman, C.; Orvain, C.; Bertrand, L.; Gourvil, P.; Probert, I.; Vacherie, B.; Brun, É.; Magdelenat, G.; Labadie, K.; et al. Transcriptomic response of the picoalga Pelagomonas calceolata to nitrogen availability: New insights into cyanate lyase function. Microbiol. Spectr. 2025, 13, e02654-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, X.; Wang, S.; Du, L.; Chen, Y.; Wang, T.; Bo, X. Metagenomics reveals the variations in functional metabolism associated with greenhouse gas emissions during legume-vegetable rotation process. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 275, 116268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Zhang, F.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, K.; Hong, Q.; Qiu, J.; He, J. Characterization of a new heterotrophic nitrification bacterium Pseudomonas sp. strain JQ170 and functional identification of nap gene in nitrite production. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 806, 150556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuypers, M.M.M.; Marchant, H.K.; Kartal, B. The microbial nitrogen-cycling network. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C.; Fang, Y.; Wang, S.; He, K. The alleviation of ammonium toxicity in plants. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2023, 65, 1362–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Guan, W.; Fan, Y.; He, Q.; Guo, D.; Yuan, A.; Xing, Q.; Wang, Y.; Ma, Z.; Ni, J.; et al. Zinc/carbon nanomaterials inhibit antibiotic resistance genes by affecting quorum sensing and microbial community in cattle manure production. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 387, 129648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.; Chen, C.; Feng, Y. Enhancement of cellulosome expression by deletion of an HtrA protein in Clostridium thermocellum. Bioresour. Technol. 2025, 434, 132841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elihasridas, N.; Pazla, R.; Zain, M.; Antonius, N.; Ikhlas, Z.; Yanti, G. Optimizing mangrove-derived tannin extract for sustainable ruminant feeding: A strategy to balance nutrient digestibility and methane mitigation. J. Anim. Behav. Biometeorol. 2025, 13, 2025012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, H.; Hashiba, H.; Kok, J.; Mierau, I. Bile Salt Hydrolase of Bifidobacterium longum—Biochemical and Genetic Characterization. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000, 66, 2502–2512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, W.; Wang, D.; Wang, Y.; Wang, C.; Chen, X.; Liu, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Kamagata, Y.; Nobu, M.K.; et al. Metatranscriptomics-guided genome-scale metabolic reconstruction reveals the carbon flux and trophic interaction in methanogenic communities. Microbiome 2024, 12, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowerman, K.L.; Lu, Y.; McRae, H.; Volmer, J.G.; Zaugg, J.; Pope, P.B.; Hugenholtz, P.; Greening, C.; Morrison, M.; Soo, R.M.; et al. Metagenomic analysis of marsupial gut microbiomes provides a genetic basis for the low methane economy [Preprint]. bioRxiv 2024, 626884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item 1 | Control | Swollenin | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial BW (kg) | 6.06 ± 0.61 | 6.26 ± 0.35 | 0.364 |

| Final BW (kg) | 8.12 ± 0.54 | 8.43 ± 0.25 | 0.104 |

| ADG 2 (g d−1) | 68.57 ± 6.69 | 72.47 ± 8.14 | 0.290 |

| ADFI 3 (g d−1) | 273.63 ± 5.77 | 263.08 ± 11.40 | 0.049 |

| Feed:gain (F/G) | 4.02 ± 0.31 | 3.67 ± 0.40 | 0.082 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, L.; Zhang, H.; Zhan, L.; Guan, W.; Hu, J.; Wei, Z.; Wu, W.; Wu, Y.; Xing, Q.; Wu, J.; et al. Synergistic Regulation of Bile Acid-Driven Nitrogen Metabolism by Swollenin in Ruminants: A Microbiota-Targeted Strategy to Improve Nitrogen Use Efficiency. Animals 2026, 16, 149. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010149

Li L, Zhang H, Zhan L, Guan W, Hu J, Wei Z, Wu W, Wu Y, Xing Q, Wu J, et al. Synergistic Regulation of Bile Acid-Driven Nitrogen Metabolism by Swollenin in Ruminants: A Microbiota-Targeted Strategy to Improve Nitrogen Use Efficiency. Animals. 2026; 16(1):149. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010149

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Lizhi, Haibo Zhang, Linfei Zhan, Weikun Guan, Junhao Hu, Zi Wei, Wenbo Wu, Yunjing Wu, Qingfeng Xing, Jianzhong Wu, and et al. 2026. "Synergistic Regulation of Bile Acid-Driven Nitrogen Metabolism by Swollenin in Ruminants: A Microbiota-Targeted Strategy to Improve Nitrogen Use Efficiency" Animals 16, no. 1: 149. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010149

APA StyleLi, L., Zhang, H., Zhan, L., Guan, W., Hu, J., Wei, Z., Wu, W., Wu, Y., Xing, Q., Wu, J., Li, Z., Liu, Q., Chen, J., Yuan, A., Guo, D., Ouyang, K., Yang, J., Hu, W., & Zhao, X. (2026). Synergistic Regulation of Bile Acid-Driven Nitrogen Metabolism by Swollenin in Ruminants: A Microbiota-Targeted Strategy to Improve Nitrogen Use Efficiency. Animals, 16(1), 149. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010149