Milk-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Inhibit Staphylococcus aureus Growth and Biofilm Formation

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Animals and Sample Collection

2.2. Extracellular Vesicles Extraction and Characterization

2.3. Isolation and Identification of Clinical Strains of S. aureus

2.4. Bacterial Culture and mEV–S. aureus Interaction Assay

2.5. Determination of Effective mEVs Concentrations and Growth Curve Analysis

2.6. Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Detection

2.7. Enzyme Activity Assays

2.8. Biofilm Formation Assay

2.9. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

2.10. Physicochemical Tolerance Assays

2.11. Biofilm Extracellular Components

2.12. RT-qPCR Analysis

2.13. Small RNA Sequencing

2.14. Target Site Prediction

2.15. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

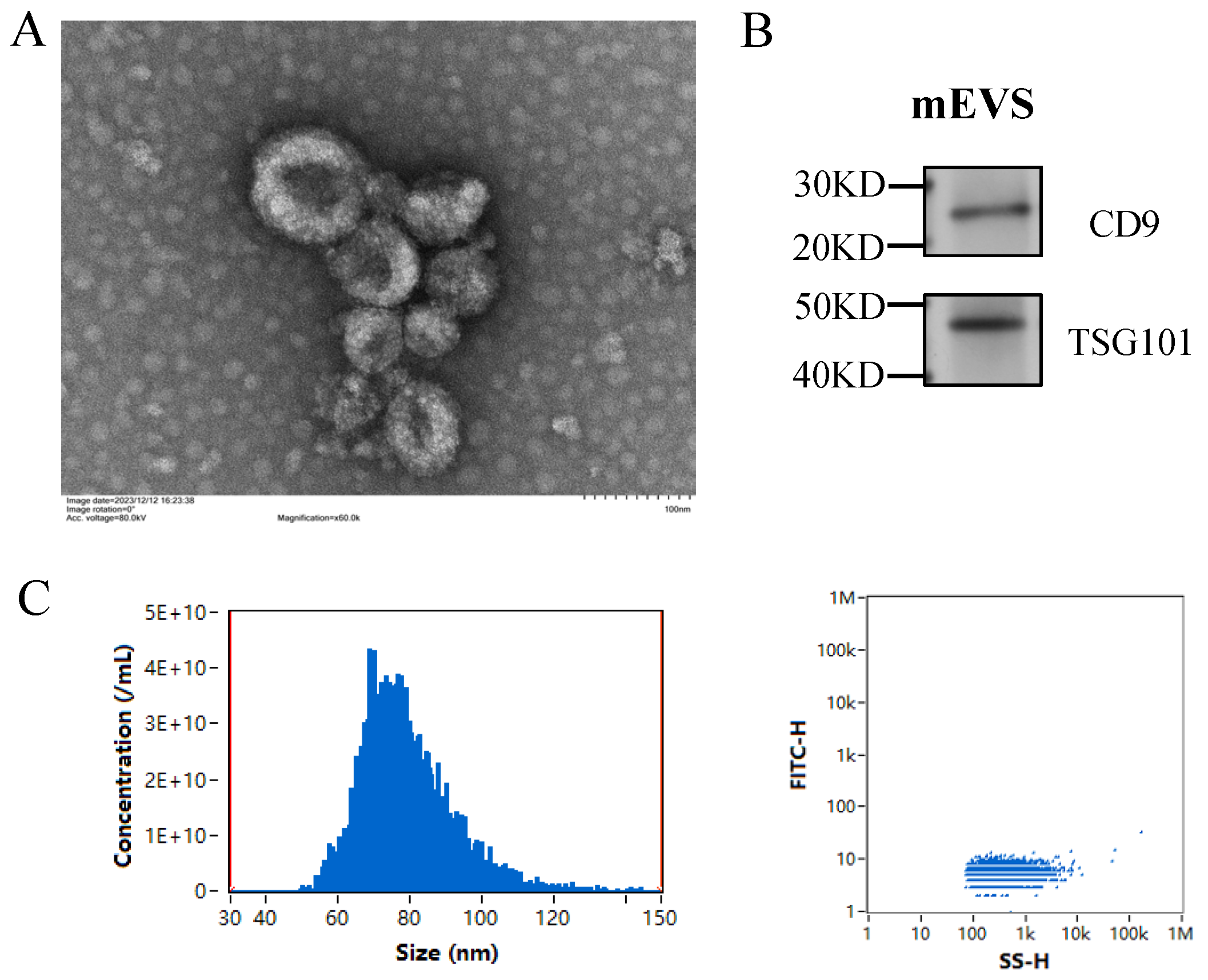

3.1. Isolation and Characterization of mEVs

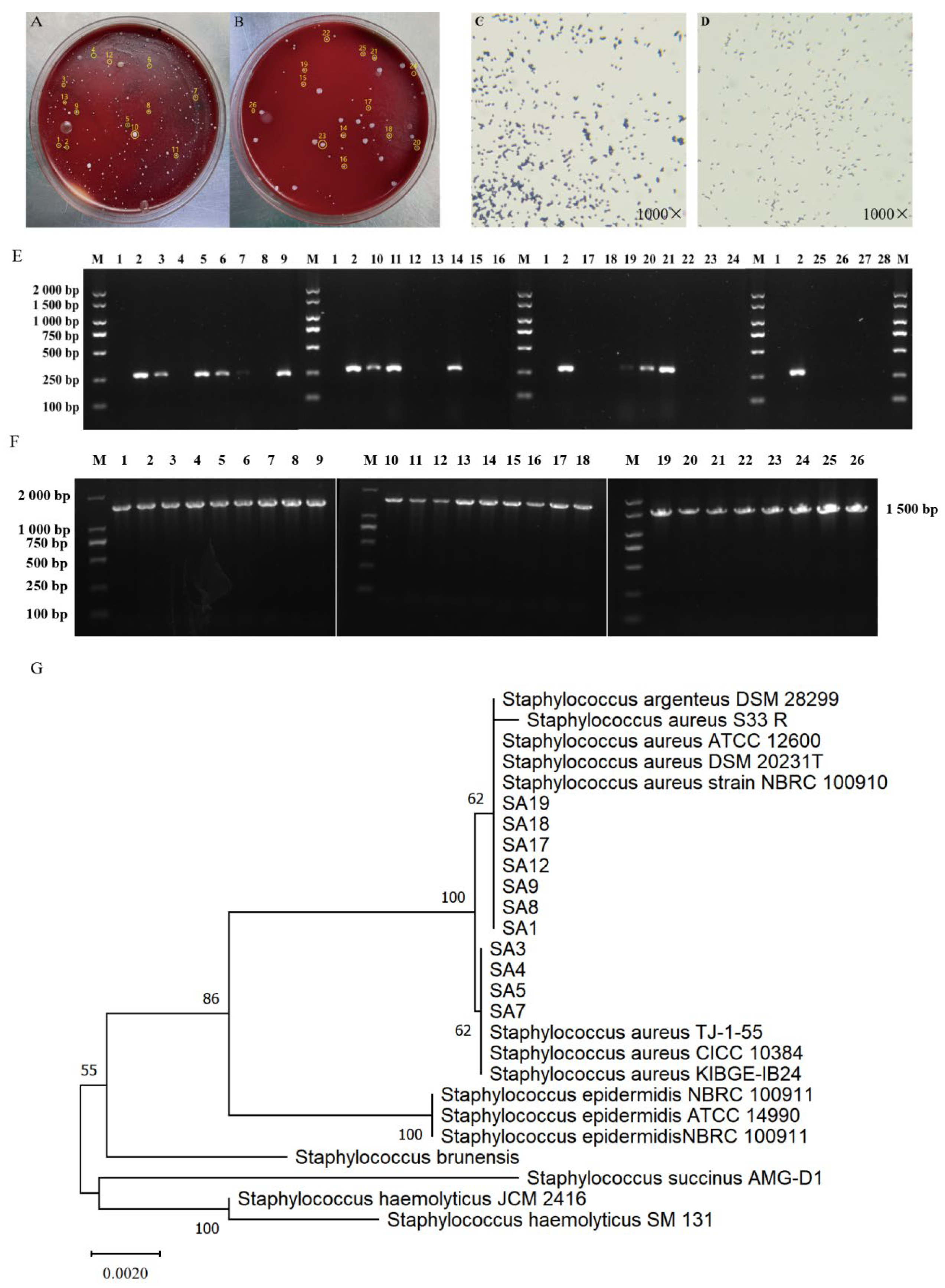

3.2. Isolation and Identification of Clinical Strains of S. aureus

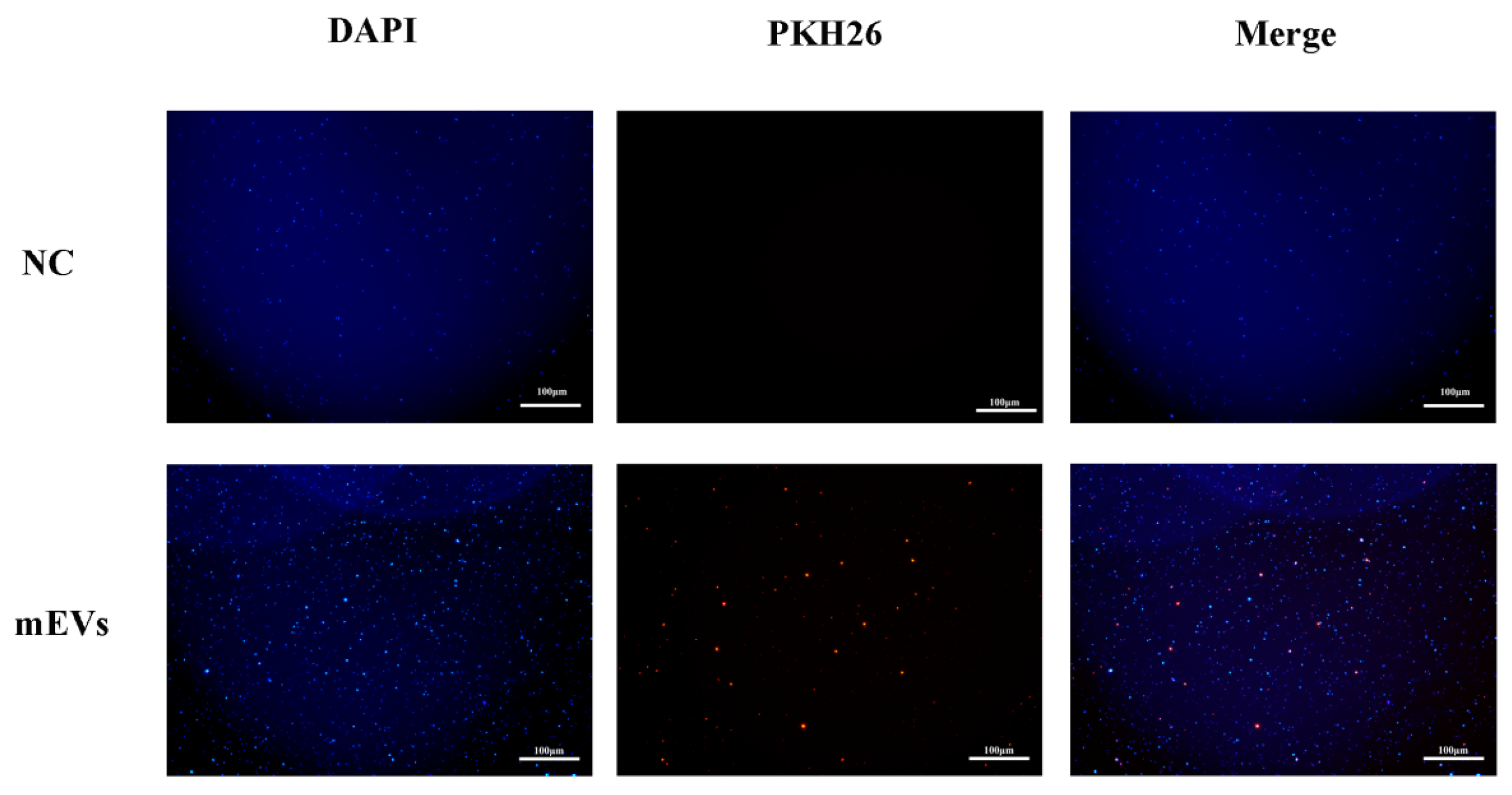

3.3. Interaction Between mEVs and S. aureus

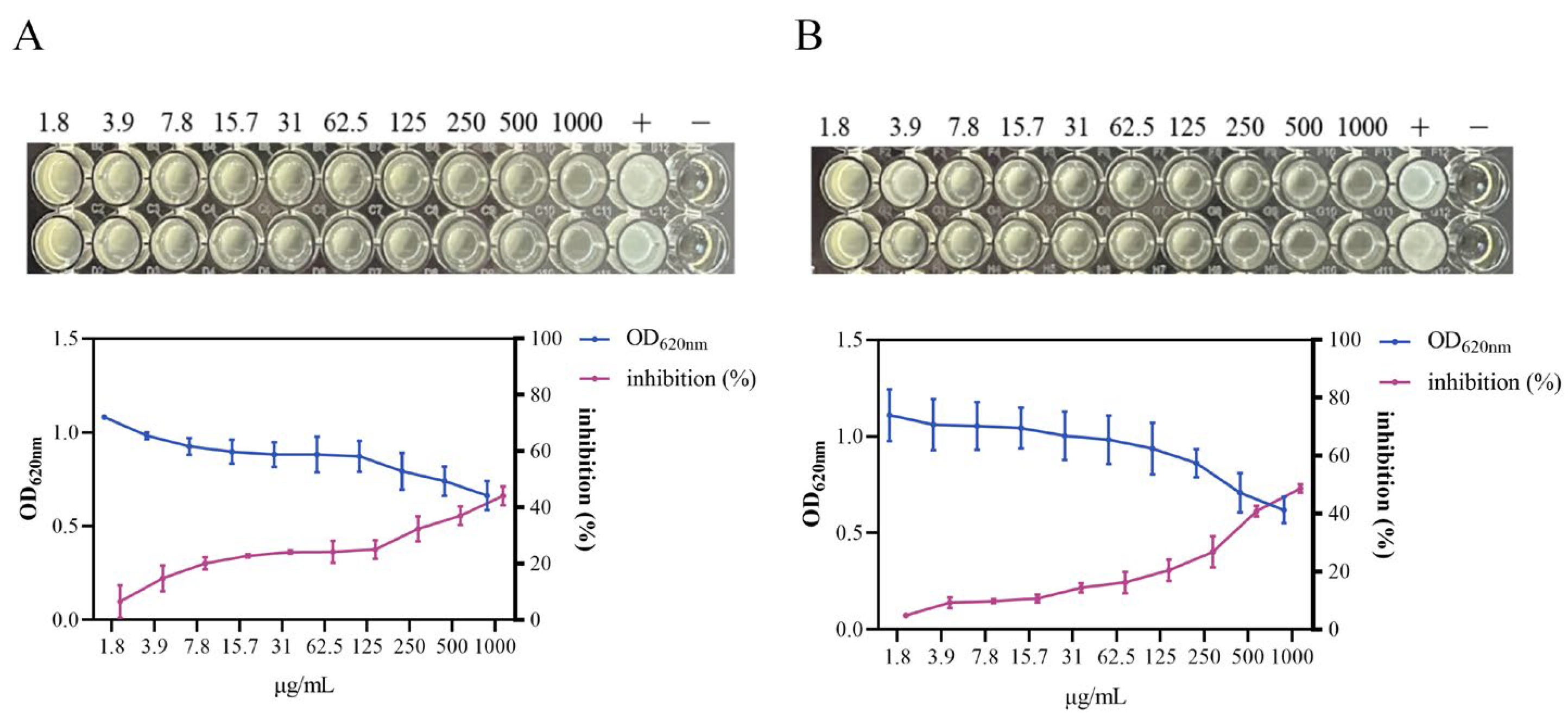

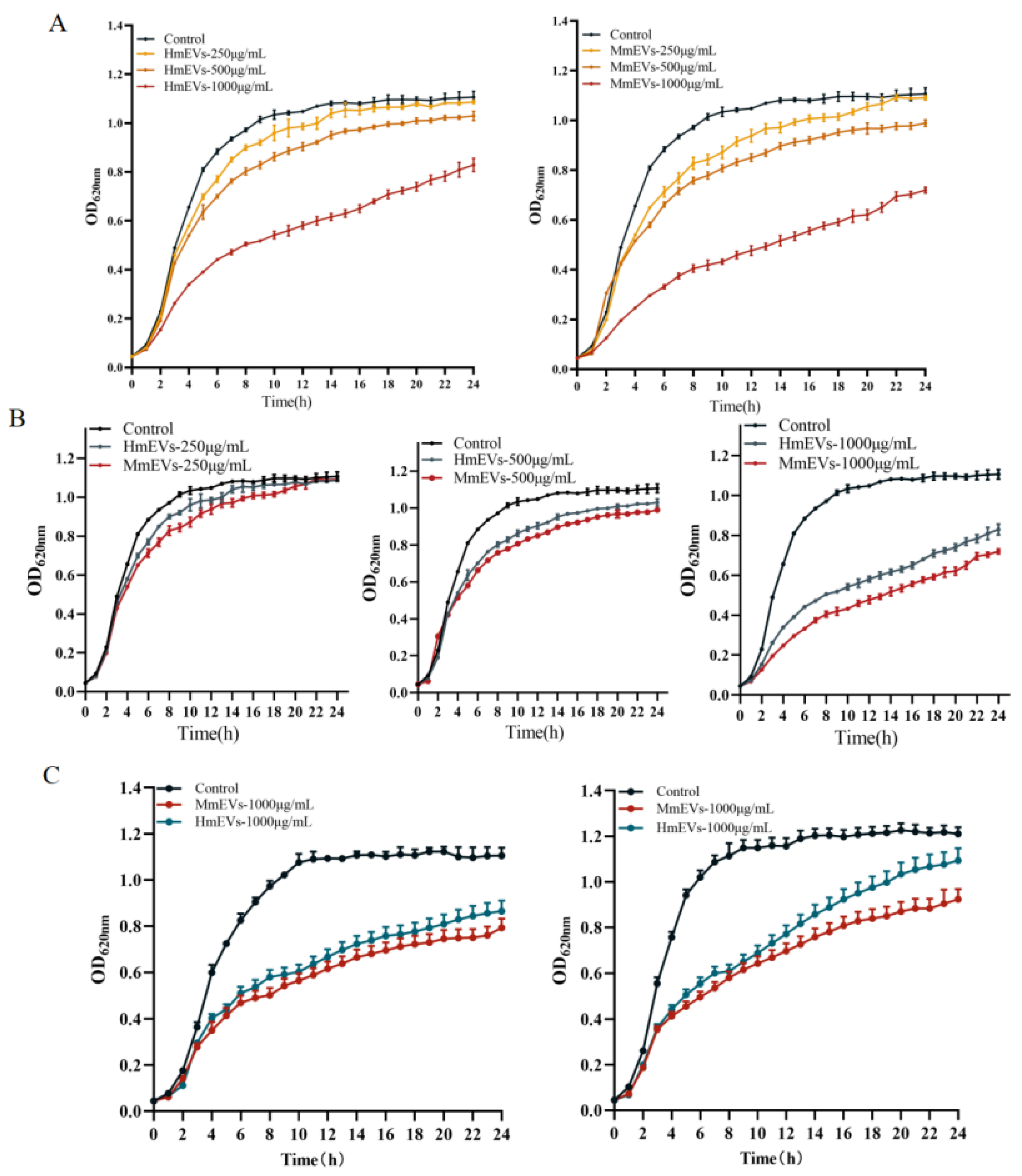

3.4. Growth Inhibition of S. aureus by HmEVs and MmEVs

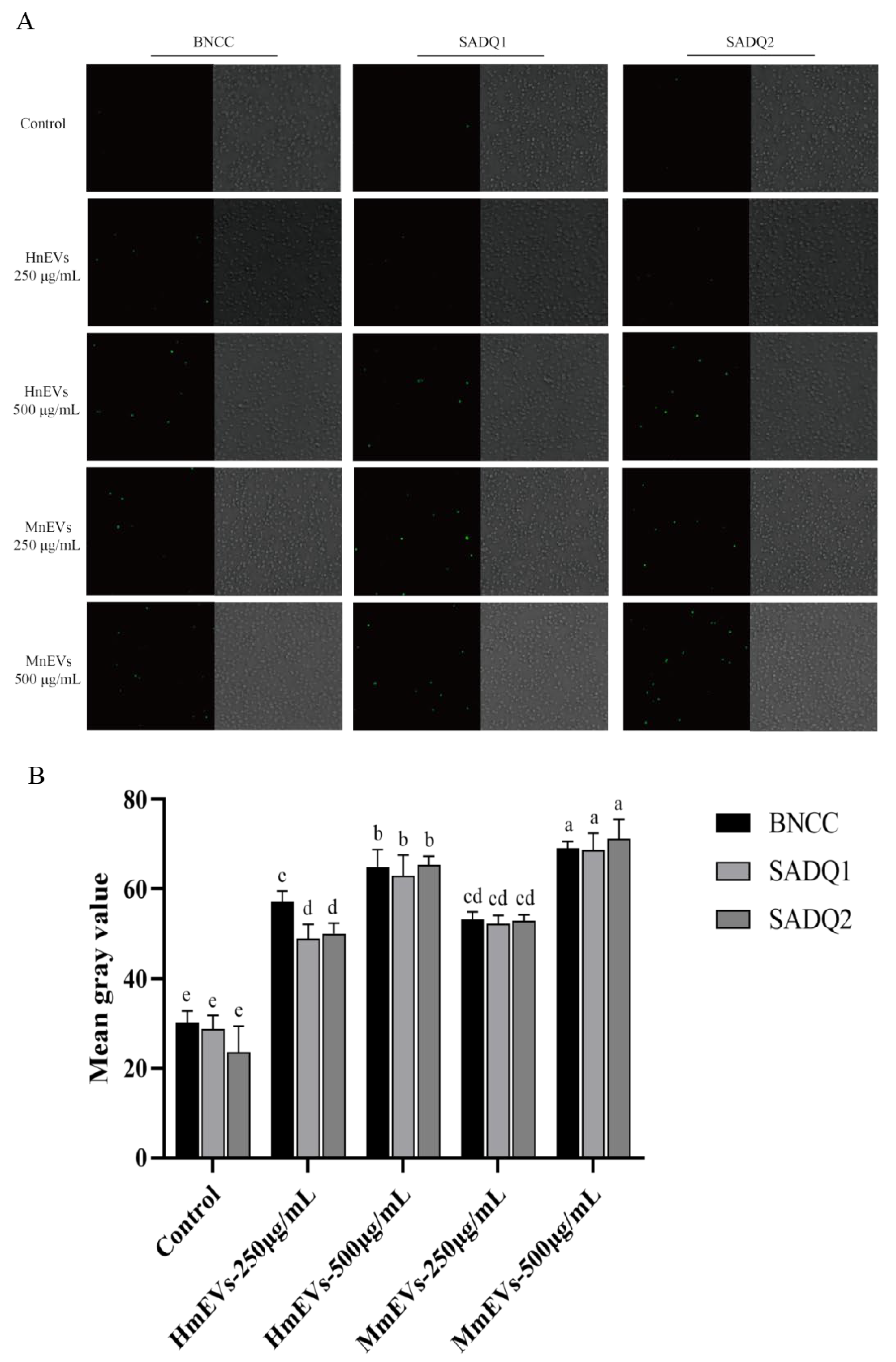

3.5. Induction of ROS by HmEVs and MmEVs

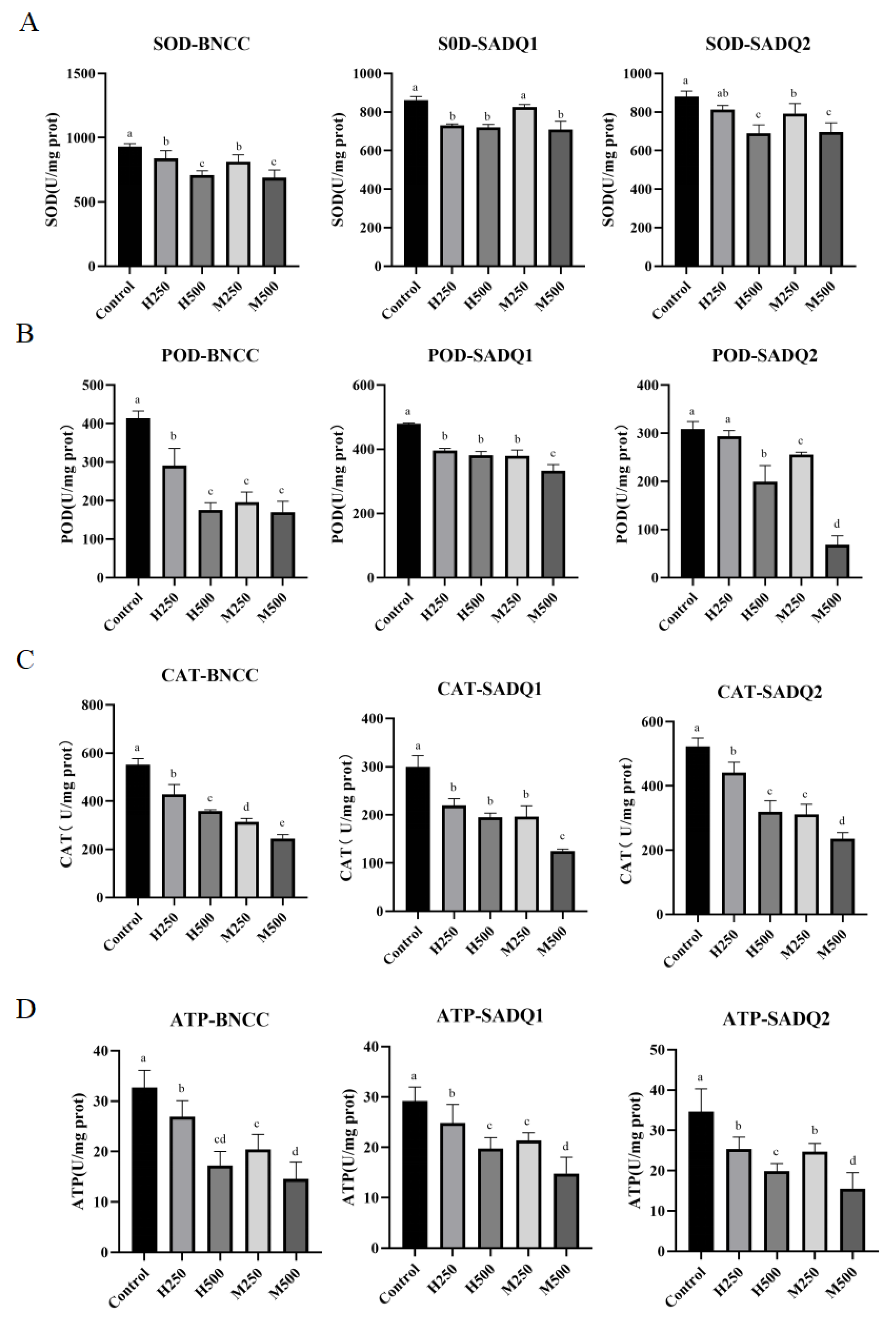

3.6. Inhibition of Antioxidant and Metabolic Enzymes by HmEVs and MmEVs

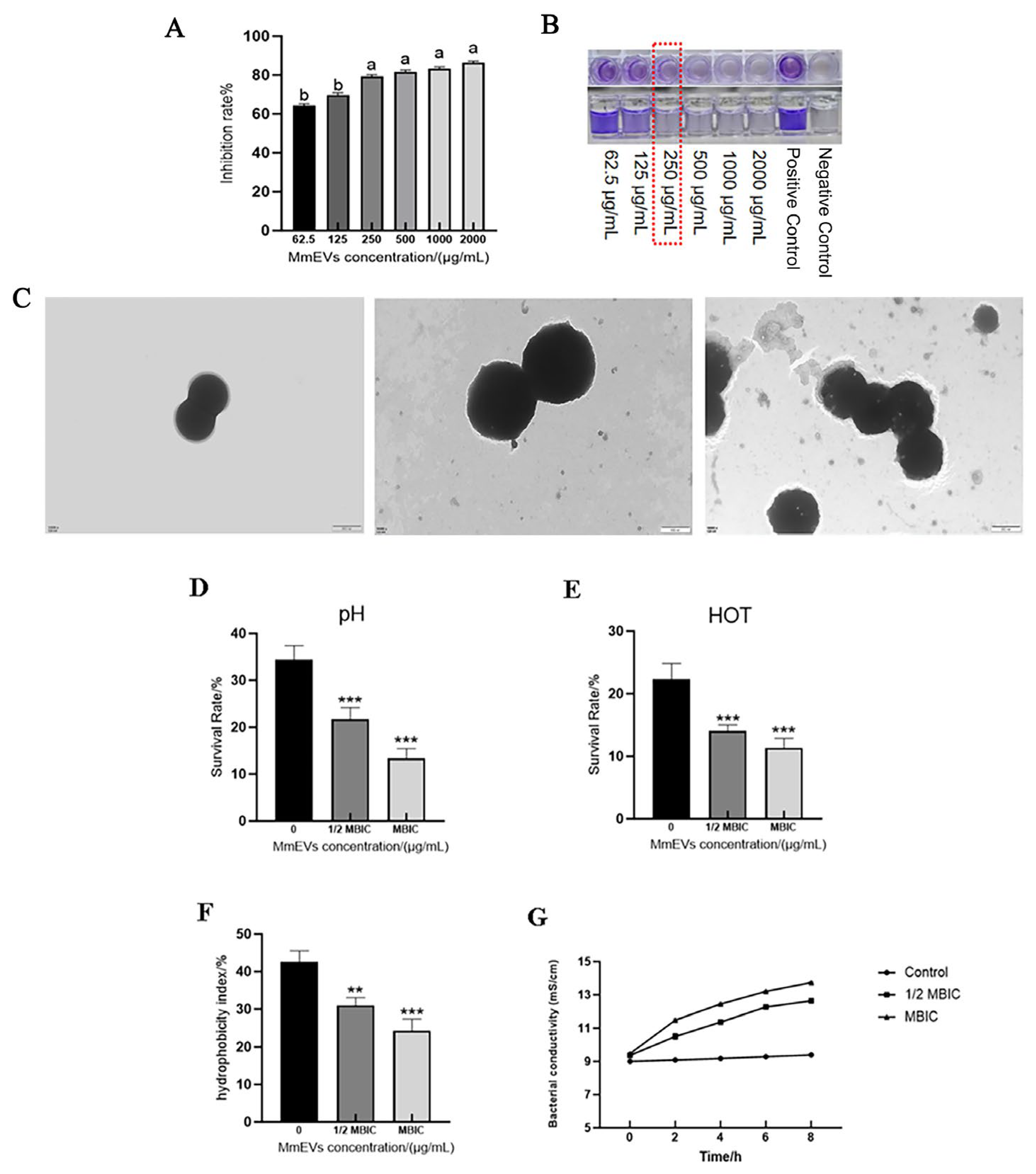

3.7. Effects of MmEVs on S. aureus Biofilm and Ultrastructure

3.8. Effects of MmEVs on the Physicochemical Tolerance of S. aureus

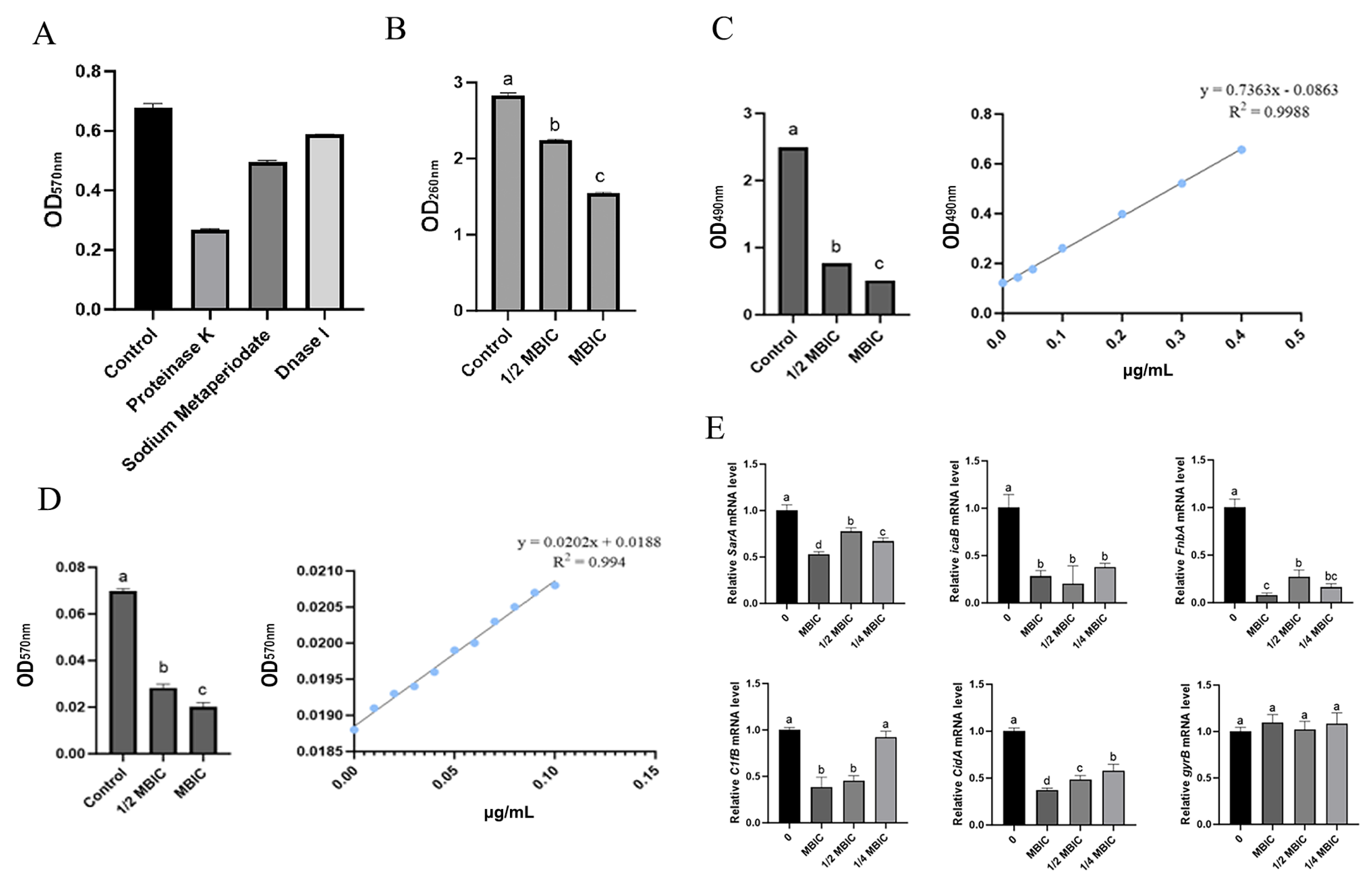

3.9. MmEV-Mediated Inhibition of Biofilm Extracellular Components and Gene Expression

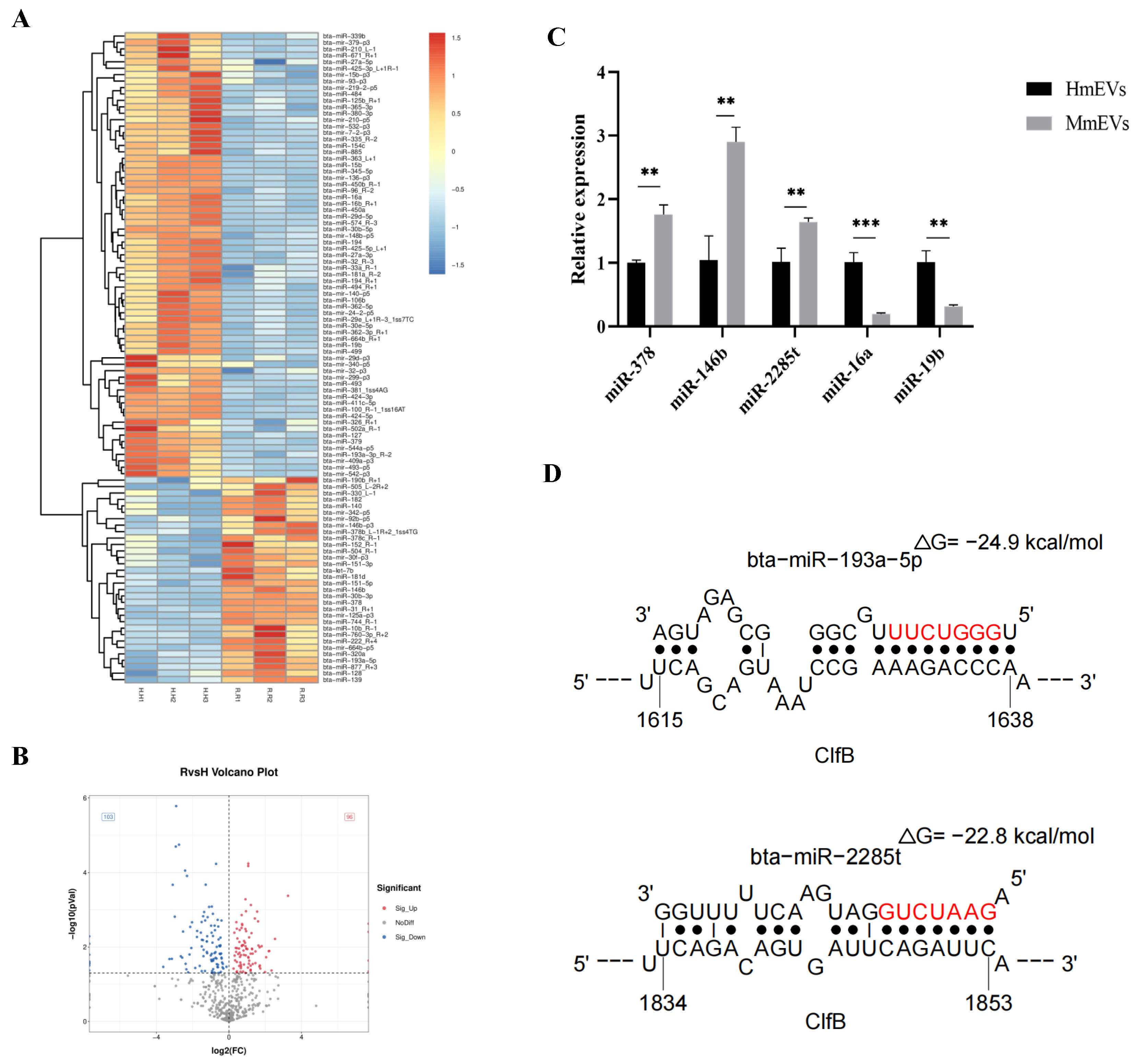

3.10. Small RNA Sequencing and Target Prediction of mEV-Derived miRNAs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zaatout, N.; Ayachi, A.; Kecha, M. Staphylococcus aureus persistence properties associated with bovine mastitis and alternative therapeutic modalities. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2020, 129, 1102–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez, V.K.C.; Costa, G.M.D.; Guimarães, A.S.; Heinemann, M.B.; Lage, A.P.; Dorneles, E.M.S. Relationship between virulence factors and antimicrobial resistance in Staphylococcus aureus from bovine mastitis. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2020, 22, 792–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seethalakshmi, P.S.; Rajeev, R.; Kiran, G.S.; Selvin, J. Promising treatment strategies to combat Staphylococcus aureus biofilm infections: An updated review. Biofouling 2020, 36, 1159–1181. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tromp, A.T.; Van Strijp, J.A.G. Studying Staphylococcal Leukocidins: A Challenging Endeavor. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Boeckel, T.P.; Brower, C.; Gilbert, M.; Grenfell, B.T.; Levin, S.A.; Robinson, T.P.; Teillant, A.; Laxminarayan, R. Global trends in antimicrobial use in food animals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 5649–5654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, K.; Yang, Y.; Gong, X.; Chen, K.; Liao, Z.; Ojha, S.C. Staphylococcal Drug Resistance: Mechanisms, Therapies, and Nanoparticle Interventions. Infect. Drug Resist. 2025, 18, 1007–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liao, T.; Wang, G.; Xu, J.; Wang, M.; Ren, F.; Zhang, H. An ultrasensitive NIR-IIa’ fluorescence-based multiplex immunochromatographic strip test platform for antibiotic residues detection in milk samples. J. Adv. Res. 2023, 50, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jank, L.; Martins, M.T.; Arsand, J.B.; Motta, T.M.C.; Feijó, T.C.; Castilhos, T.d.S.; Hoff, R.B.; Barreto, F.; Pizzolato, T.M. Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry Multiclass Method for 46 Antibiotics Residues in Milk and Meat: Development and Validation. Food Anal. Methods 2017, 10, 2152–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaac, R.; Reis, F.C.G.; Ying, W.; Olefsky, J.M. Exosomes as mediators of intercellular crosstalk in metabolism. Cell Metab. 2021, 33, 1744–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’bRien, K.; Breyne, K.; Ughetto, S.; Laurent, L.C.; Breakefield, X.O. RNA delivery by extracellular vesicles in mammalian cells and its applications. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 585–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meldolesi, J. Exosomes and Ectosomes in Intercellular Communication. Curr. Biol. 2018, 28, R435–R444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liu, X.; Tyler, B.M. Biogenesis and Biological Functions of Extracellular Vesicles in Cellular and Organismal Communication With Microbes. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 817844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabatke, B.; Rossi, I.V.; Bonato, L.; Fucio, S.; Cortés, A.; Marcilla, A.; Ramirez, M.I. Host–Pathogen Cellular Communication: The Role of Dynamin, Clathrin, and Macropinocytosis in the Uptake of Giardia-Derived Extracellular Vesicles. ACS Infect. Dis. 2025, 11, 954–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuh, C.M.A.P.; Aguayo, S.; Zavala, G.; Khoury, M. Exosome-like vesicles in Apis mellifera bee pollen, honey and royal jelly contribute to their antibacterial and pro-regenerative activity. J. Exp. Biol. 2019, 222, jeb208702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, S.; Zhao, Z.; Xu, X.; Li, M.; Li, P. Characterization of three different types of extracellular vesicles and their impact on bacterial growth. Food Chem. 2019, 272, 372–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiemstra, T.F.; Charles, P.D.; Gracia, T.; Hester, S.S.; Gatto, L.; Al-Lamki, R.; Floto, R.A.; Su, Y.; Skepper, J.N.; Lilley, K.S.; et al. Human urinary exosomes as innate immune effectors. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2014, 25, 2017–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; He, Z.; Leone, S.; Liu, S. Milk Exosomes Transfer Oligosaccharides into Macrophages to Modulate Immunity and Attenuate Adherent-Invasive, E. coli (AIEC) Infection. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunnaike, M.; Wang, H.; Zempleni, J. Bovine mammary alveolar MAC-T cells afford a tool for studies of bovine milk exosomes in drug delivery. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 610, 121263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Wuren, T.; Zhai, B.; Liu, Y.; Er, D. Milk-derived exosomes in the regulation of nutritional and immune functions. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 12, 7048–7059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yáñez-Mó, M.; Siljander, P.R.-M.; Andreu, Z.; Bedina Zavec, A.; Borràs, F.E.; Buzas, E.I.; Buzas, K.; Casal, E.; Cappello, F.; Carvalho, J.; et al. Biological properties of extracellular vesicles and their physiological functions. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2015, 4, 27066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timar, C.I.; Lőrincz, M.; Csepanyi-Komi, R.; Vályi-Nagy, A.; Nagy, G.; Buzás, E.; Iványi, Z.; Kittel, Á.; Powell, D.W.; McLeish, K.R.; et al. Antibacterial effect of microvesicles released from human neutrophilic granulocytes. Blood 2013, 121, 510–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y.; Bi, J.; Lin, Y.; He, J.; Wu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Song, S.; Guo, H. Milk-derived small extracellular vesicles promote bifidobacteria growth by accelerating carbohydrate metabolism. LWT 2023, 182, 114866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brakhage, A.A.; Zimmermann, A.-K.; Rivieccio, F.; Visser, C.; Blango, M.G. Host-derived extracellular vesicles for antimicrobial defense. Microlife 2021, 2, uqab003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastos, M.L.C.; Ferreira, G.G.; Kosmiscky, I.O.; Guedes, I.M.L.; Muniz, J.A.P.C.; Carneiro, L.A.; Peralta, Í.L.C.; Bahia, M.N.M.; Souza, C.O.; Dolabela, M.F. What Do We Know About Staphylococcus aureus and Oxidative Stress? Resistance, Virulence, New Targets, and Therapeutic Alternatives. Toxics 2025, 13, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Cao, Y.; Xu, X.; Wang, C.; Ni, Q.; Lv, X.; Yang, C.; Zhang, Z.; Qi, X.; Song, G. Sleep Deprivation Promotes Endothelial Inflammation and Atherogenesis by Reducing Exosomal miR-182-5p. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2023, 43, 995–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Bassler, B.L. Surviving as a Community: Antibiotic Tolerance and Persistence in Bacterial Biofilms. Cell Host Microbe 2019, 26, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramton, S.E.; Gerke, C.; Schnell, N.F.; Nichols, W.W.; Gotz, F. The intercellular adhesion (ica) locus is present in Staphylococcus aureus and is required for biofilm formation. Infect. Immun. 1999, 67, 5427–5433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tormo, M.A.; Martí, M.; Valle, J.; Manna, A.C.; Cheung, A.L.; Lasa, I.; Penadés, J.R. SarA is an essential positive regulator of Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilm development. J. Bacteriol. 2005, 187, 2348–2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gries, C.M.; Biddle, T.; Bose, J.L.; Kielian, T.; Lo, D.D. Staphylococcus aureus Fibronectin Binding Protein A Mediates Biofilm Development and Infection. Infect. Immun. 2020, 88, e00859-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashi, M.; Noei, M.; Chegini, Z.; Shariati, A. Natural compounds in the fight against Staphylococcus aureus biofilms: A review of antibiofilm strategies. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1491363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, K.C.; Mann, E.E.; Endres, J.L.; Weiss, E.C.; Cassat, J.E.; Smeltzer, M.S.; Bayles, K.W. The cidA murein hydrolase regulator contributes to DNA release and biofilm development in Staphylococcus aureus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 8113–8118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chunxing, X.; Jingdi, C.; Xiang, L.; Ruicong, W.; Yu, C.; Yanwu, L.; Xiang, H.; Jingjing, Z.; Taoran, W.; Jiakai, G.; et al. The inhibitory effect of extracellular vesicles derived from S. epidermidis on MRSA biofilms. Int. J. Pharm. 2025, 683, 126067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, G.; Shin, W.R.; Lee, S.; Yoon, H.W.; Choi, J.W.; Kim, Y.H.; Ahn, J.Y. Bovine Colostrum Exosomes Are a Promising Natural Bacteriostatic Agent against Staphylococcus aureus. ACS Infect. Dis. 2023, 9, 993–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Hou, D.; Chen, X.; Li, D.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Bian, Z.; Liang, X.; Cai, X.; et al. Exogenous plant MIR168a specifically targets mammalian LDLRAP1: Evidence of cross-kingdom regulation by microRNA. Cell Res. 2012, 22, 107–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; da Cunha, A.P.; Rezende, R.M.; Cialic, R.; Wei, Z.; Bry, L.; Comstock, L.E.; Gandhi, R.; Weiner, H.L. The Host Shapes the Gut Microbiota via Fecal MicroRNA. Cell Host Microbe 2016, 19, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, P.; Wang, Z.; Gao, Z.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Song, Y.; Li, X.; Song, H.; He, X.; Kong, F.; et al. Milk-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Inhibit Staphylococcus aureus Growth and Biofilm Formation. Animals 2026, 16, 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010123

Liu P, Wang Z, Gao Z, Liu J, Zhang Y, Song Y, Li X, Song H, He X, Kong F, et al. Milk-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Inhibit Staphylococcus aureus Growth and Biofilm Formation. Animals. 2026; 16(1):123. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010123

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Peng, Zhaoyuan Wang, Ziqiang Gao, Juan Liu, Yutong Zhang, Yangyang Song, Xiaolin Li, Huaxue Song, Xingli He, Fanzhi Kong, and et al. 2026. "Milk-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Inhibit Staphylococcus aureus Growth and Biofilm Formation" Animals 16, no. 1: 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010123

APA StyleLiu, P., Wang, Z., Gao, Z., Liu, J., Zhang, Y., Song, Y., Li, X., Song, H., He, X., Kong, F., Wang, C., & Shen, B. (2026). Milk-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Inhibit Staphylococcus aureus Growth and Biofilm Formation. Animals, 16(1), 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010123