Hermetia illucens Larvae Meal Enhances Colonic Antimicrobial Peptide Expression by Promoting Histone Acetylation in Weaned Piglets Challenged with ETEC in Pig Housing

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal Treatment

2.2. Simulation of K88 Challenged Environment

2.3. Sample Collection

2.4. DNA Extraction and Measurement of Intestinal Bacterial Populations by Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR)

2.5. Serum Cytokines and Immunoglobulin Determined by ELISA

2.6. Quantitative Real-Time PCR

2.7. Western Blot

2.8. Immunofluorescence

2.9. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

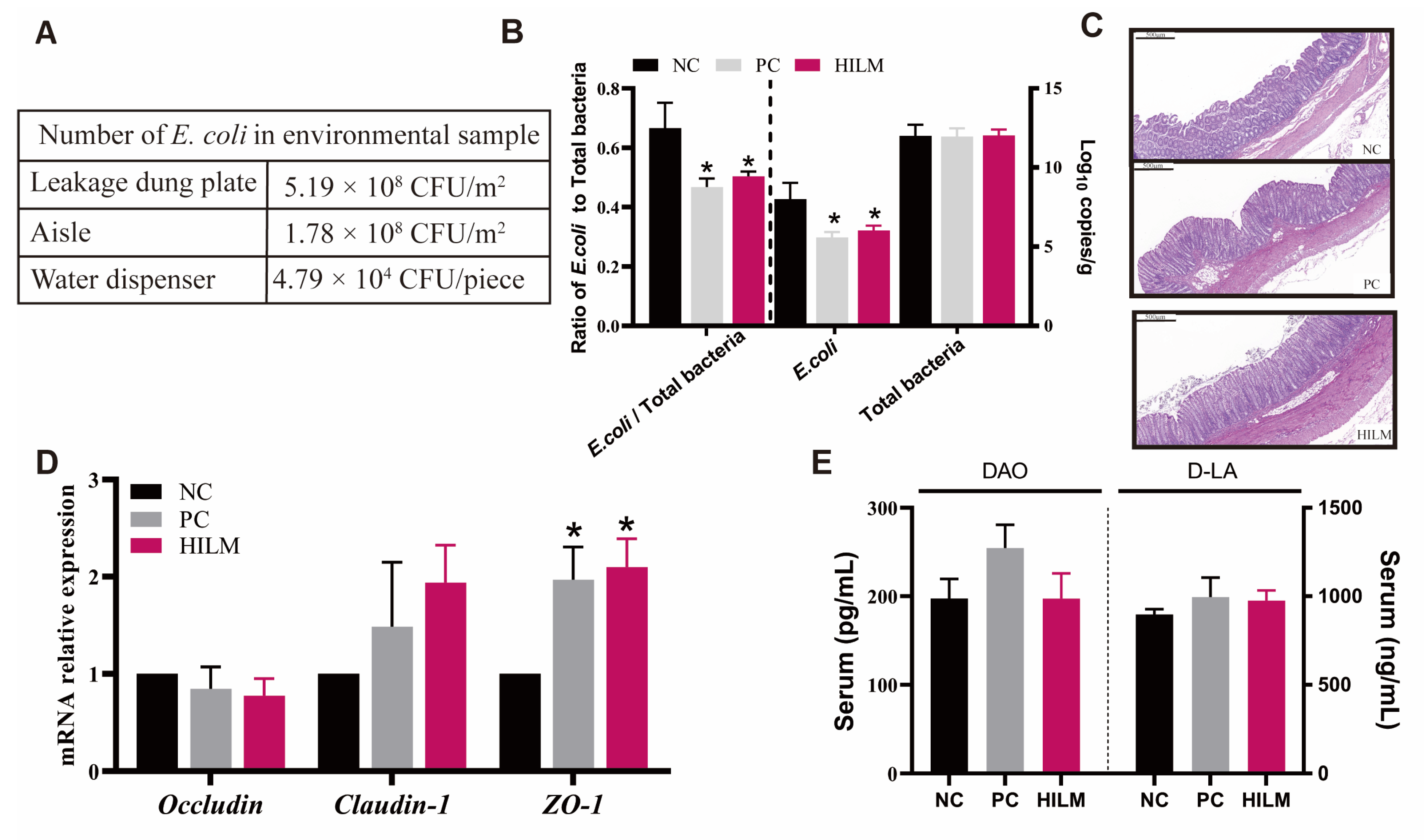

3.1. The Number of E. coli in Environment and Colonic Digesta of Weaned Piglets in ETEC-Challenged Pig Housing

3.2. Effect of Dietary HILM on Relative Weight of Organ and Colonic Barrier Function of Weaned Piglets in ETEC-Challenged Pig Housing

3.3. Effects of Dietary HILM on Cytokine Production and Immunoglobulin of Weaned Piglets in ETEC-Challenged Pig Housing

3.4. Effects of Dietary HILM on Immune Response and Histone Acetylation Modifications of Weaned Piglets in ETEC-Challenged Pig Housing

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kim, S.W.; Less, J.F.; Wang, L.; Yan, T.; Kiron, V.; Kaushik, S.J.; Lei, X.G. Meeting global feed protein demand: Challenge, opportunity, and strategy. Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci. 2019, 7, 221–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosch, G.; Bosch, G. Insects: A protein-rich feed ingredient in pig and poultry diets. Anim. Front. 2015, 5, 45–50. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Q.; Xu, E.; Wang, Z.; Xiao, M.; Cao, S.; Hu, S.; Wu, Q.; Xiong, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Wang, F.; et al. Dietary Hermetia illucens larvae meal improves growth performance and intestinal barrier function of weaned pigs under the environment of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli k88. Front. Nutr. 2022, 8, 812011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Huis, A. Potential of insects as food and feed in assuring food security. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2013, 58, 563–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barragan-Fonseca, K.; Dicke, M.; van Loon, J. Nutritional value of the black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens L.) And its suitability as animal feed—A review. J. Insects. Food. Feed. 2017, 3, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Li, Z.; Chen, W.; Rong, T.; Wang, G.; Ma, X. Hermetia illucens larvae as a potential dietary protein source altered the microbiota and modulated mucosal immune status in the colon of finishing pigs. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2019, 10, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Li, Z.; Chen, W.; Wang, G.; Rong, T.; Liu, Z.; Wang, F.; Ma, X. Hermetia illucens larvae as a fishmeal replacement alters intestinal specific bacterial populations and immune homeostasis in weanling piglets. J. Anim. Sci. 2020, 98, skz395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, M.; Fei, S.; Xia, J.; Labropoulou, V.; Swevers, L.; Sun, J. Antimicrobial peptides as potential antiviral factors in insect antiviral immune response. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Ge, C.; Yao, H. Antimicrobial peptides from black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) as potential antimicrobial factors representing an alternative to antibiotics in livestock farming. Animals 2021, 11, 1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngendahayo Mukiza, C.; Dubreuil, J.D. Escherichia coli heat-stable toxin b impairs intestinal epithelial barrier function by altering tight junction proteins. Infect. Immun. 2013, 81, 2819–2827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilling, J.D.; Mulvey, M.A.; Vincent, C.D.; Lorenz, R.G.; Hultgren, S.J. Bacterial invasion augments epithelial cytokine responses to Escherichia coli through a lipopolysaccharide-dependent mechanism. J. Immunol. 2001, 166, 1148–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Luo, X.; Fang, G.; Zhan, S.; Wu, J.; Wang, D.; Huang, Y. Transgenic expression of antimicrobial peptides from black soldier fly enhance resistance against entomopathogenic bacteria in the silkworm, bombyx mori. Insect. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2020, 127, 103487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagat, M.K.; Were, S.; Ndwigah, F.; Kemboi, V.J.; Kipkoech, C.; Tanga, C.M. Antimicrobial activity of chemically and biologically treated chitosan prepared from black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) pupal shell waste. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.; Shin, D.; Kim, J.; Hong, S.; Choi, D.; Kim, Y.; Kwak, M.; Jung, Y. Caffeic acid phenethyl ester-mediated nrf2 activation and IkappaB kinase inhibition are involved in NFkappaB inhibitory effect: Structural analysis for NFkappaB inhibition. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2010, 643, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehart, H.; Kumpf, S.; Ittner, A.; Ricci, R. MAPK signalling in cellular metabolism: Stress or wellness? EMBO Rep. 2010, 11, 834–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, N.; Sechet, E.; Friedman, R.; Amiot, A.; Sobhani, I.; Nigro, G.; Sansonetti, P.J.; Sperandio, B. Histone deacetylase inhibition enhances antimicrobial peptide but not inflammatory cytokine expression upon bacterial challenge. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E2993–E3001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, M.T.; Taylor, L.T.; DeLong, E.F. Quantitative analysis of small-subunit rRNA genes in mixed microbial populations via 5′-nuclease assays. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000, 66, 4605–4614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huijsdens, X.W.; Linskens, R.K.; Mak, M.; Meuwissen, S.G.; Vandenbroucke-Grauls, C.M.; Savelkoul, P.H. Quantification of bacteria adherent to gastrointestinal mucosa by real-time PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2002, 40, 4423–4427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, H.; Hu, W.; Chen, S.; Lu, Z.; Wang, Y. Cathelicidin-WA improves intestinal epithelial barrier function and enhances host defense against enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli o157:h7 infection. J. Immunol. 2017, 198, 1696–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhag, O.; Zhou, D.; Song, Q.; Soomro, A.A.; Cai, M.; Zheng, L.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, J. Screening, expression, purification and functional characterization of novel antimicrobial peptide genes from Hermetia illucens (L.). PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0169582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruni, L.; Pastorelli, R.; Viti, C.; Gasco, L.; Parisi, G. Characterisation of the intestinal microbial communities of rainbow trout (oncorhynchus mykiss) fed with Hermetia illucens (black soldier fly) partially defatted larva meal as partial dietary protein source. Aquaculture 2018, 487, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombino, E.; Biasato, I.; Ferrocino, I.; Bellezza Oddon, S.; Caimi, C.; Gariglio, M.; Dabbou, S.; Caramori, M.; Battisti, E.; Zanet, S.; et al. Effect of insect live larvae as environmental enrichment on poultry gut health: Gut mucin composition, microbiota and local immune response evaluation. Animals 2021, 11, 2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.I.; Yoe, S.M. A novel cecropin-like peptide from black soldier fly, Hermetia illucens: Isolation, structural and functional characterization. Entomol. Res. 2017, 47, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candian, V.; Savio, C.; Meneguz, M.; Gasco, L.; Tedeschi, R. Effect of the rearing diet on gene expression of antimicrobial peptides in Hermetia illucens (diptera: Stratiomyidae). Insect. Sci. 2023, 30, 933–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, Y.; Lin, H.; Chang, C.; Lin, S.; Lin, J.H. Dynamic expression of cathepsin l in the black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) gut during Escherichia coli challenge. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0298338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harhaj, N.S.; Antonetti, D.A. Regulation of tight junctions and loss of barrier function in pathophysiology. Int. Int. J. Biochem. Cell. Biol. 2004, 36, 1206–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittig, B.; Zeitz, M. The gut as an organ of immunology. Int. J. Colorectal. Dis. 2003, 18, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Fu, Q.; Li, X.; Luo, Y.; Luo, J.; Chen, D.; Mao, X.; Yu, B.; Zheng, P.; Huang, Z.; et al. Human β-defensin 118 attenuates Escherichia coli k88-induced inflammation and intestinal injury in mice. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2021, 13, 586–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veldhuizen, E.J.A.; Schneider, V.A.F.; Agustiandari, H.; van Dijk, A.; Tjeerdsma-van Bokhoven, J.L.M.; Bikker, F.J.; Haagsman, H.P. Antimicrobial and immunomodulatory activities of PR-39 derived peptides. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e95939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Liu, Y.; Shen, T.; Chen, L.; Zhang, C.; Cai, K.; Liu, Z.; Meng, X.; Zhang, L.; Liao, C.; et al. Enhancing the antibacterial activity of PMAP-37 by increasing its hydrophobicity. Chem. Biol. Drug. Des. 2019, 94, 1986–1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Moll, L.; De Smet, J.; Paas, A.; Tegtmeier, D.; Vilcinskas, A.; Cos, P.; Van Campenhout, L. In vitro evaluation of antimicrobial peptides from the black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) against a selection of human pathogens. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e0166421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Che, D.; Adams, S.; Zhao, B.; Qin, G.; Jiang, H. Effects of dietary l-arginine supplementation from conception to post- weaning in piglets. Curr. Protein. Pept. Sci. 2019, 20, 736–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorpe, C.M.; Hurley, B.P.; Lincicome, L.L.; Jacewicz, M.S.; Keusch, G.T.; Acheson, D.W. Shiga toxins stimulate secretion of interleukin-8 from intestinal epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 1999, 67, 5985–5993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trevejo-Nunez, G.; Elsegeiny, W.; Conboy, P.; Chen, K.; Kolls, J.K. Critical role of IL-22/IL22-RA1 signaling in pneumococcal pneumonia. J. Immunol. 2016, 197, 1877–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cario, E.; Rosenberg, I.M.; Brandwein, S.L.; Beck, P.L.; Reinecker, H.C.; Podolsky, D.K. Lipopolysaccharide activates distinct signaling pathways in intestinal epithelial cell lines expressing toll-like receptors. J. Immunol. 2000, 164, 966–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Ogino, S.; Qian, Z.R. Toll-like receptor signaling in colorectal cancer: Carcinogenesis to cancer therapy. World. J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 17699–17708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Liu, J.; Ma, Y.; Wei, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, H. Impairment of intestinal barrier function induced by early weaning via autophagy and apoptosis associated with gut microbiome and metabolites. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 804870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, H.; Guo, B.; Gan, Z.; Song, D.; Lu, Z.; Yi, H.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Du, H. Butyrate upregulates endogenous host defense peptides to enhance disease resistance in piglets via histone deacetylase inhibition. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 27070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scuto, A.; Kirschbaum, M.; Buettner, R.; Kujawski, M.; Cermak, J.M.; Atadja, P.; Jove, R. SIRT1 activation enhances HDAC inhibition-mediated upregulation of GADD45g by repressing the binding of NF-κb/STAT3 complex to its promoter in malignant lymphoid cells. Cell. Death. Dis. 2013, 4, e635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellman, A.S.; Metukuri, M.R.; Kazgan, N.; Xu, X.; Xu, Q.; Ren, N.S.X.; Czopik, A.; Shanahan, M.T.; Kang, A.; Chen, W.; et al. Intestinal epithelial sirtuin 1 regulates intestinal inflammation during aging in mice by altering the intestinal microbiota. Gastroenterology 2017, 153, 772–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Xu, J.; Xiong, X.; Deng, Y. Salidroside inhibits MAPK, NF-κb, and STAT3 pathways in psoriasis-associated oxidative stress via SIRT1 activation. Redox. Rep. 2019, 24, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Items | NC | PC | HILM | SEM | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart weight (g) | 106.94 | 129.23 | 117.86 | 3.90 | 0.105 |

| Liver weight (g) | 874.22 | 863.34 | 835.50 | 29.96 | 0.877 |

| Spleen weight (g) | 61.91 | 67.32 | 53.92 | 2.78 | 0.139 |

| Lung weight (g) | 222.59 | 259.41 | 248.08 | 6.87 | 0.072 |

| Kidney weight (g) | 122.44 | 137.57 | 129.24 | 4.22 | 0.362 |

| Heart weight: BW (%) | 0.52 | 0.55 | 0.51 | 0.01 | 0.221 |

| Liver weight: BW (%) | 4.24 a | 3.6 b | 3.59 b | 0.10 | 0.002 |

| Spleen weight: BW (%) | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.23 | 0.02 | 0.179 |

| Lung weight: BW (%) | 1.08 | 1.11 | 1.07 | 0.02 | 0.792 |

| Kidney weight: BW (%) | 0.59 | 0.59 | 0.55 | 0.02 | 0.571 |

| Items | NC | PC | HILM | SEM | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-1β ng/L | 373.05 a | 317.57 b | 352.71 ab | 9.71 | 0.050 |

| IL-6 ng/L | 59.52 | 78.30 | 59.78 | 4.22 | 0.110 |

| IL-8 ng/L | 34.00 a | 29.19 a | 13.52 b | 3.42 | 0.001 |

| IL-10 ng/L | 51.60 b | 65.46 a | 63.53 a | 2.36 | 0.022 |

| TNF-α ng/L | 171.83 | 172.10 | 196.08 | 21.74 | 0.886 |

| TGF-β ng/L | 146.48 | 146.34 | 150.12 | 8.75 | 0.851 |

| IgA μg/mL | 58.54 | 63.95 | 64.02 | 1.87 | 0.414 |

| IgM μg/mL | 60.65 b | 85.00 a | 65.5 ab | 4.45 | 0.050 |

| IgG μg/mL | 283.09 b | 325.14 ab | 369.10 a | 15.27 | 0.048 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tang, Q.; Wu, G.; Xu, W.; Liu, J.; Liu, H.; Zhong, B.; Wu, Q.; Yang, X.; Wang, L.; Jiang, Z.; et al. Hermetia illucens Larvae Meal Enhances Colonic Antimicrobial Peptide Expression by Promoting Histone Acetylation in Weaned Piglets Challenged with ETEC in Pig Housing. Animals 2026, 16, 118. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010118

Tang Q, Wu G, Xu W, Liu J, Liu H, Zhong B, Wu Q, Yang X, Wang L, Jiang Z, et al. Hermetia illucens Larvae Meal Enhances Colonic Antimicrobial Peptide Expression by Promoting Histone Acetylation in Weaned Piglets Challenged with ETEC in Pig Housing. Animals. 2026; 16(1):118. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010118

Chicago/Turabian StyleTang, Qingsong, Guixing Wu, Wentuo Xu, Jingxi Liu, Huiliang Liu, Bin Zhong, Qiwen Wu, Xuefeng Yang, Li Wang, Zongyong Jiang, and et al. 2026. "Hermetia illucens Larvae Meal Enhances Colonic Antimicrobial Peptide Expression by Promoting Histone Acetylation in Weaned Piglets Challenged with ETEC in Pig Housing" Animals 16, no. 1: 118. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010118

APA StyleTang, Q., Wu, G., Xu, W., Liu, J., Liu, H., Zhong, B., Wu, Q., Yang, X., Wang, L., Jiang, Z., & Yi, H. (2026). Hermetia illucens Larvae Meal Enhances Colonic Antimicrobial Peptide Expression by Promoting Histone Acetylation in Weaned Piglets Challenged with ETEC in Pig Housing. Animals, 16(1), 118. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010118