Immune-Modulatory Mechanism of Compound Yeast Culture in the Liver of Weaned Lambs

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Compound Yeast Culture

2.2. Experimental Design and Animal Diets

2.3. Sample Collection

2.4. Observation of the Histological Structure of Liver Tissue

2.5. Determination of Hepatic Immune and Antioxidant Parameters

2.5.1. Determination of Hepatic Immune Cytokine Levels by ELISA

2.5.2. Detection of Relative mRNA Expression Levels of Hepatic Immune Cytokine Levels in Liver Tissue by qRT-PCR

2.5.3. Determination of Oxidative Stress–Related Parameters

2.6. Transcriptome Sequencing

2.6.1. RNA Extraction

2.6.2. Library Preparation and Sequencing

2.6.3. Quality Control and Comparison Analysis

2.6.4. Differential Expression Analysis and Functional Enrichment

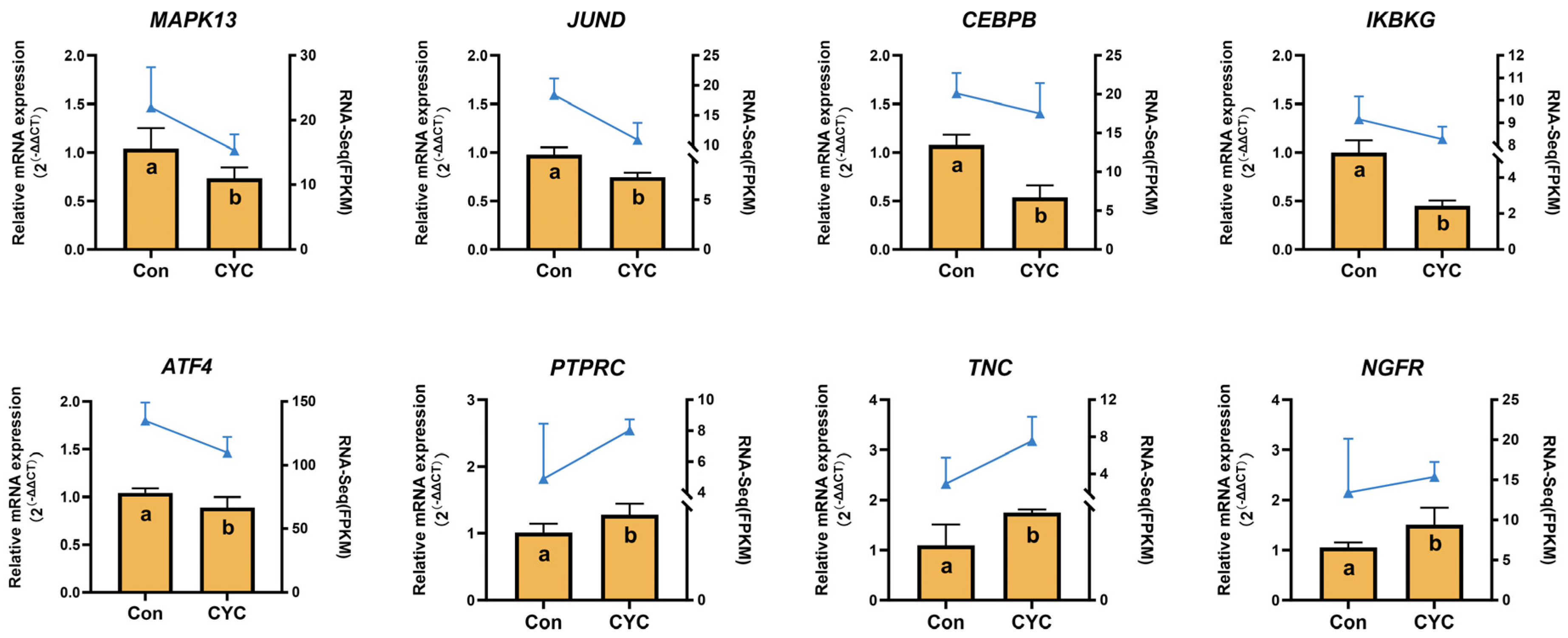

2.6.5. Validation of Transcriptome Differential Expression Genes

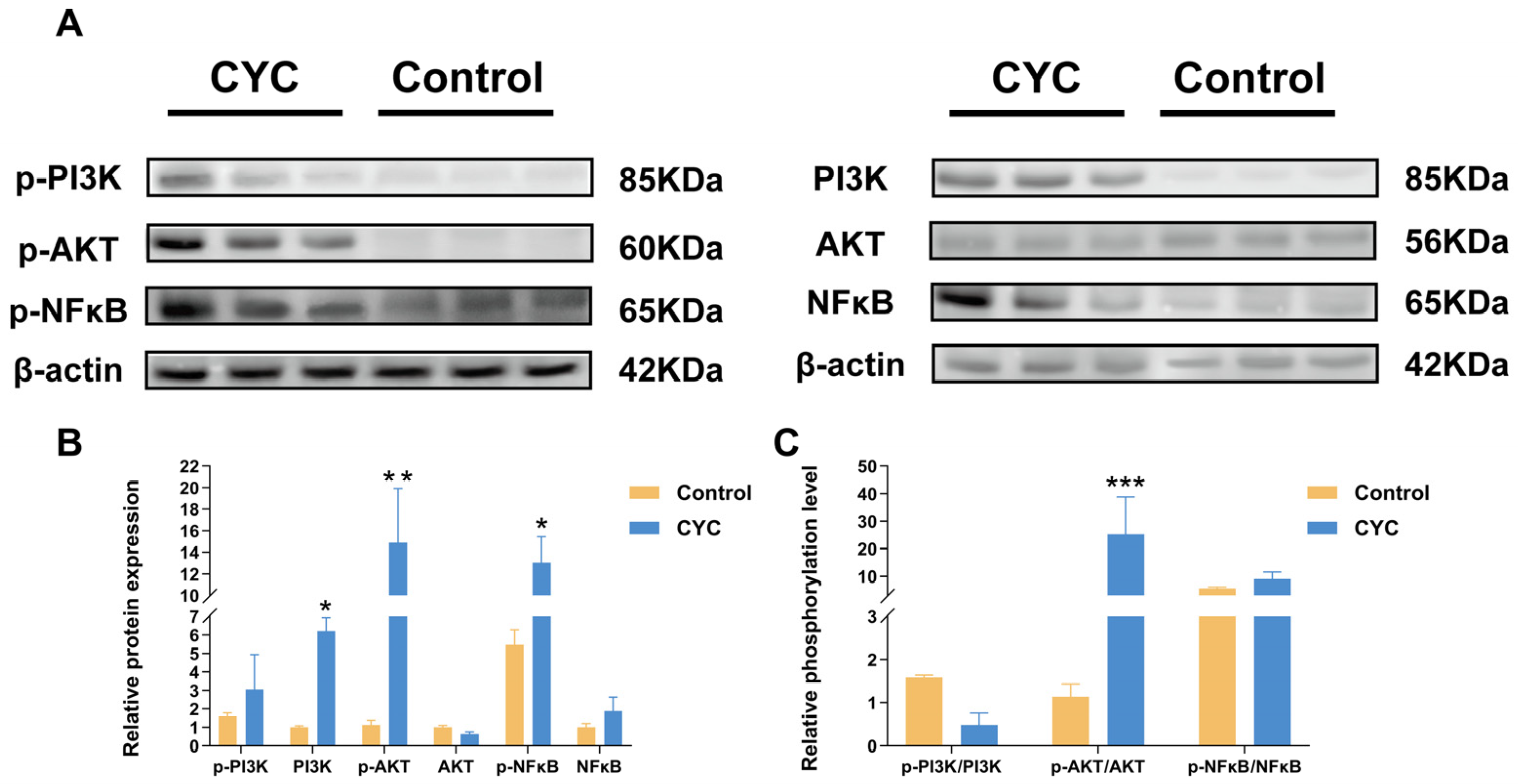

2.6.6. Validation of Transcriptome-Identified Signaling Pathways by Western Blot

2.7. Statistical Analysis

2.7.1. Data Statistics and Significance Testing

2.7.2. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA)

2.7.3. Weighted Gene Co-Expression Network Analysis

3. Results

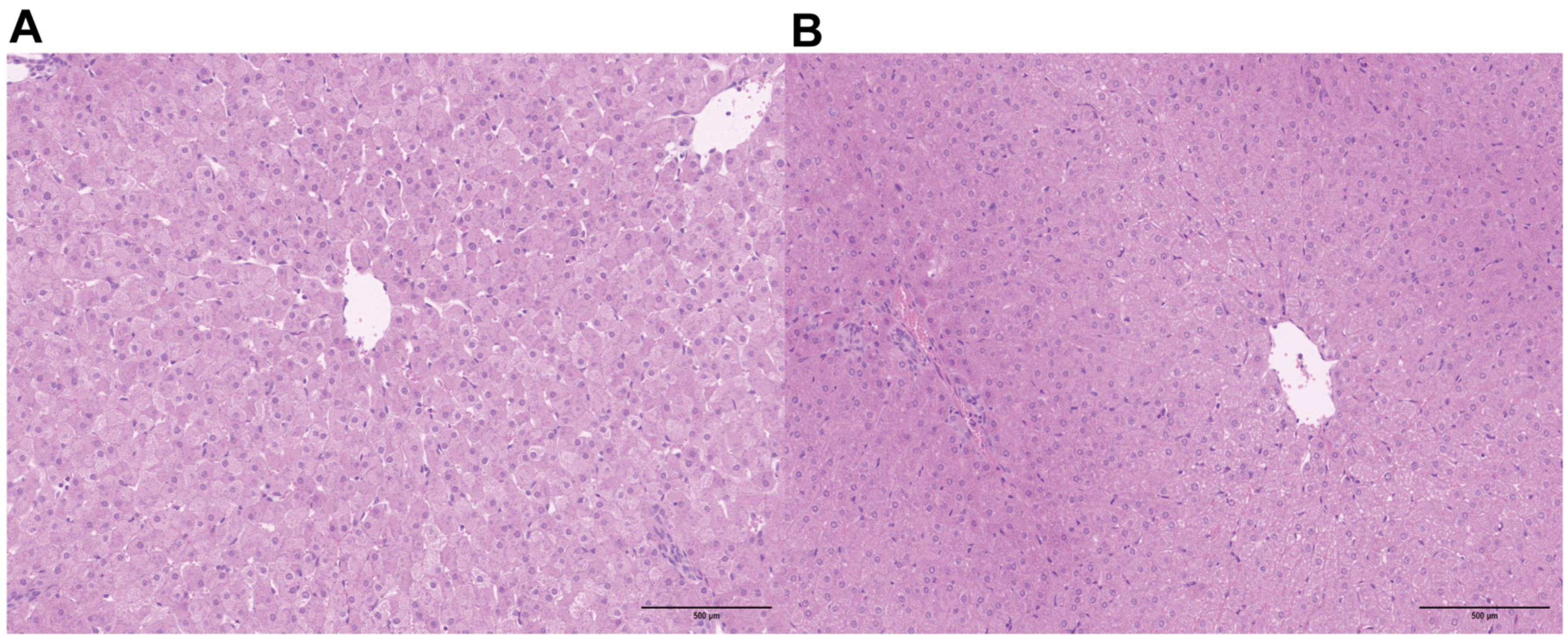

3.1. Effects of Compound Yeast Culture on the Histomorphological Structure of Lamb Liver Tissue

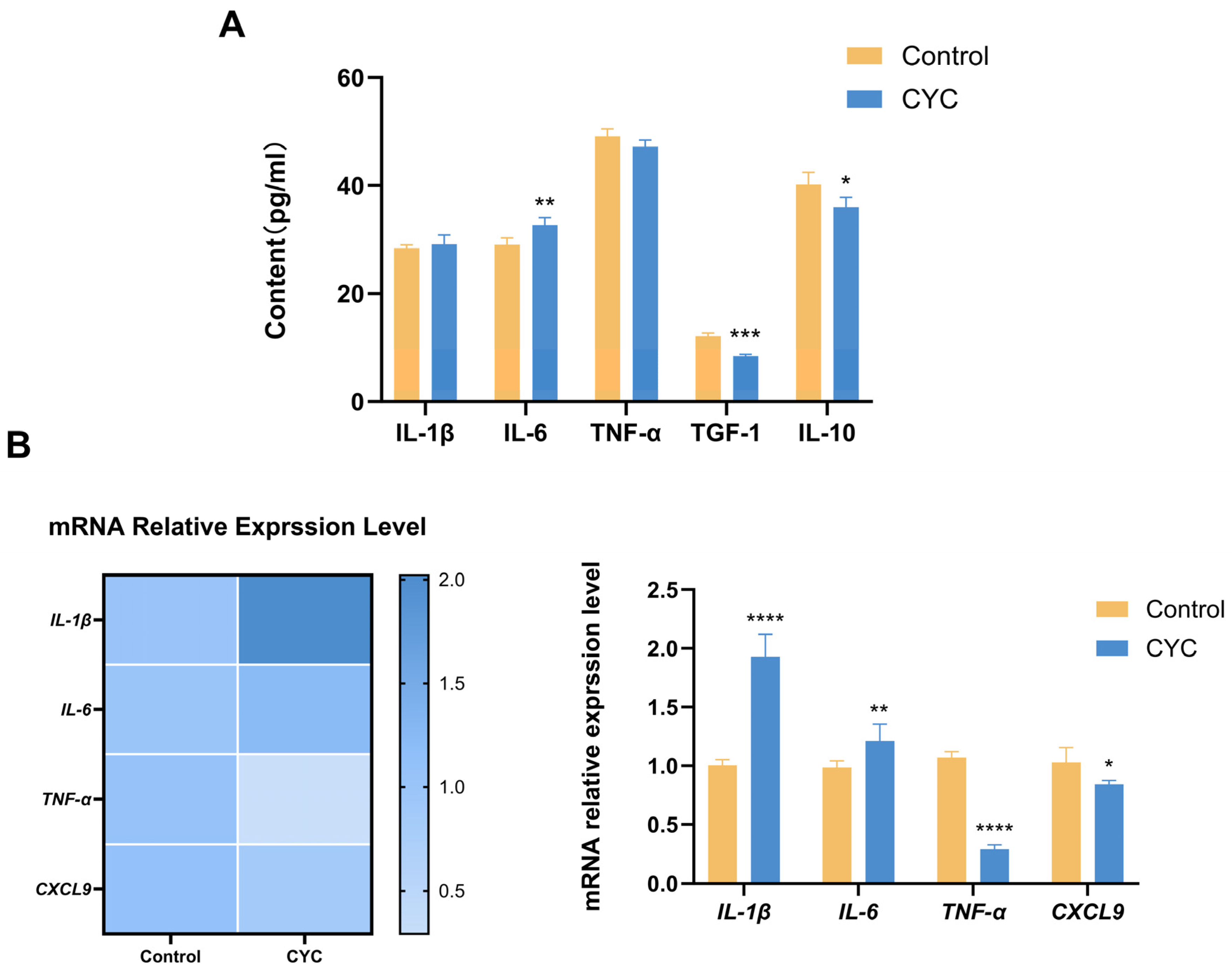

3.2. Effects of Compound Yeast Culture on Immune Factors in Lamb Liver Tissue

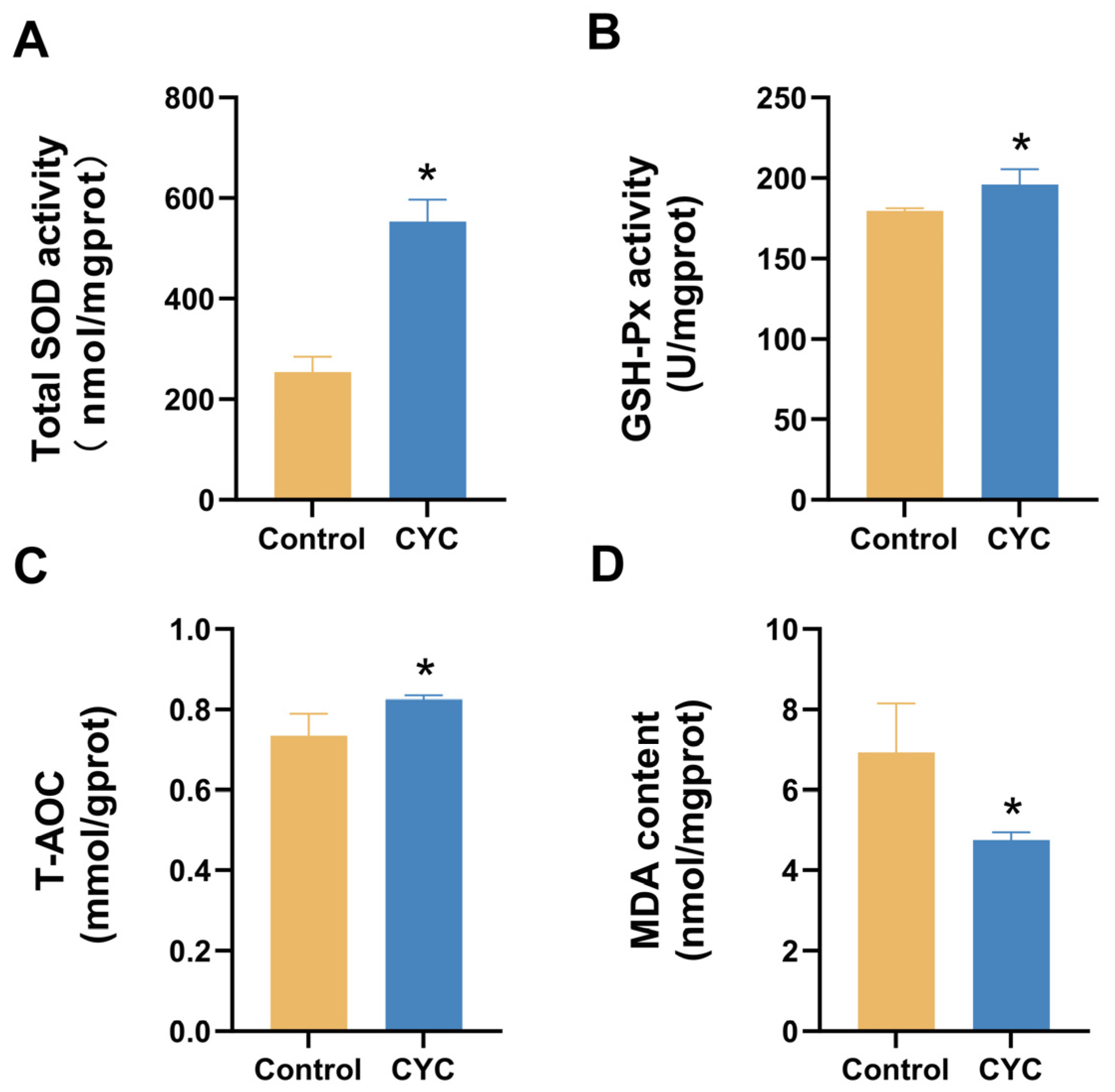

3.3. Effects of Compound Yeast Culture on Hepatic Antioxidant and Oxidative Stress Parameters in Lambs

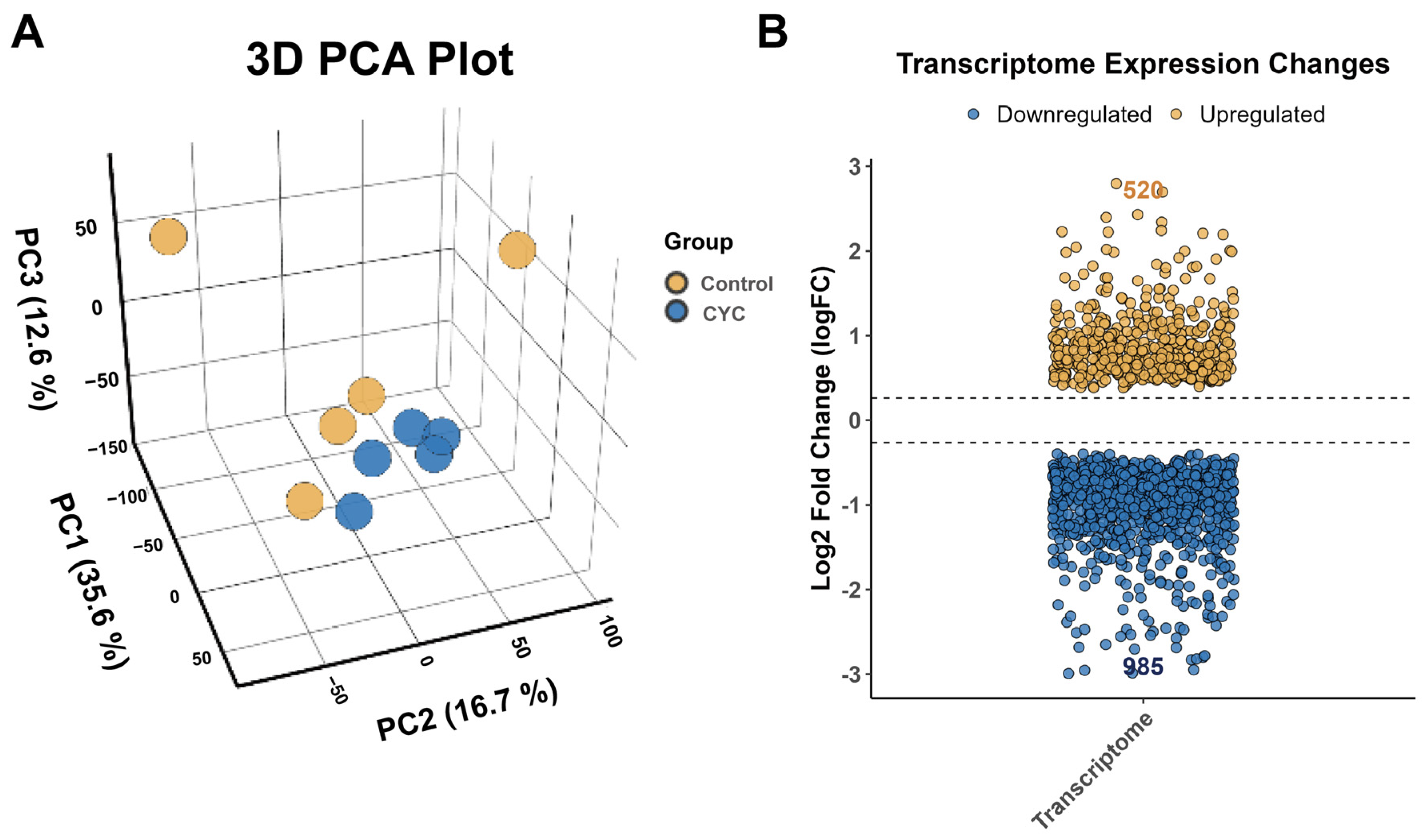

3.4. Transcriptomic Analysis of Lamb Liver Following Compound Yeast Culture Supplementation

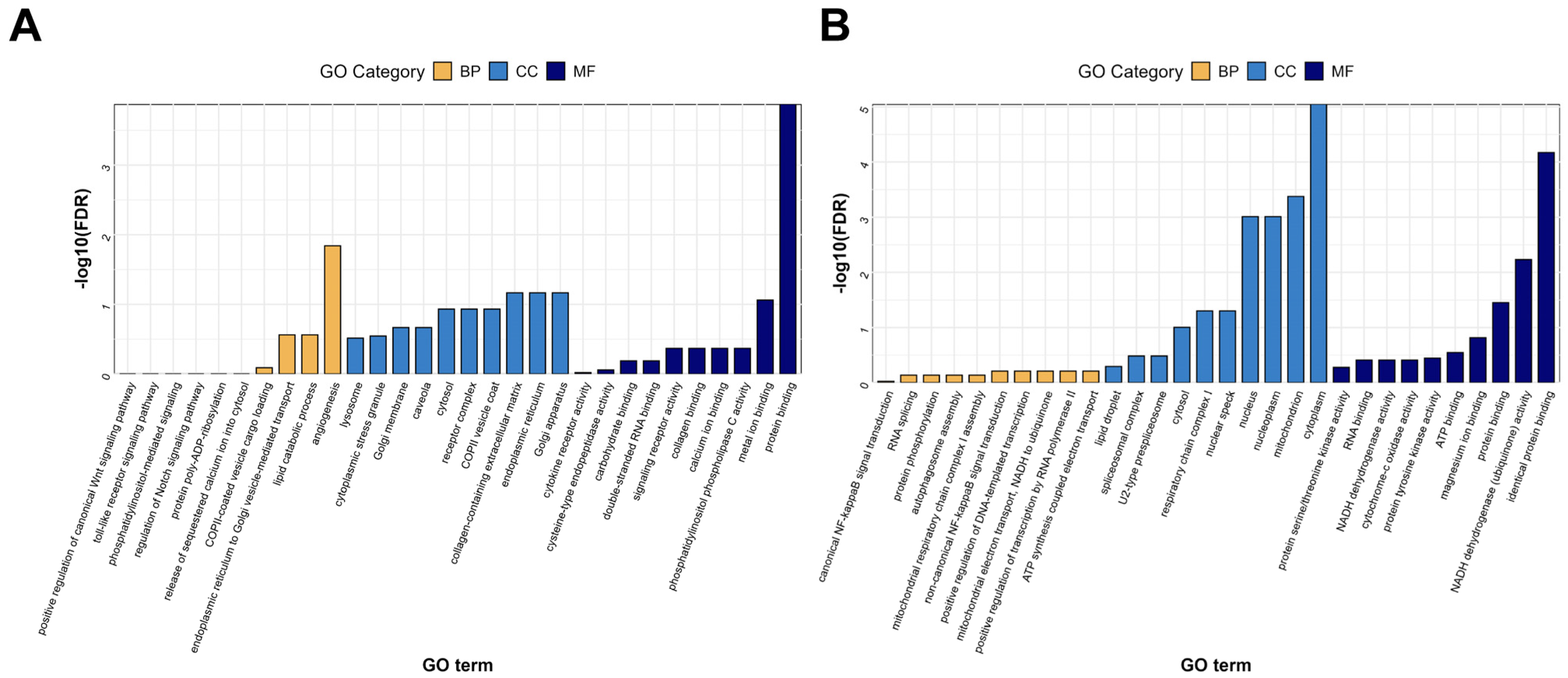

3.4.1. Gene Ontology (GO) Functional Analysis of DEGs

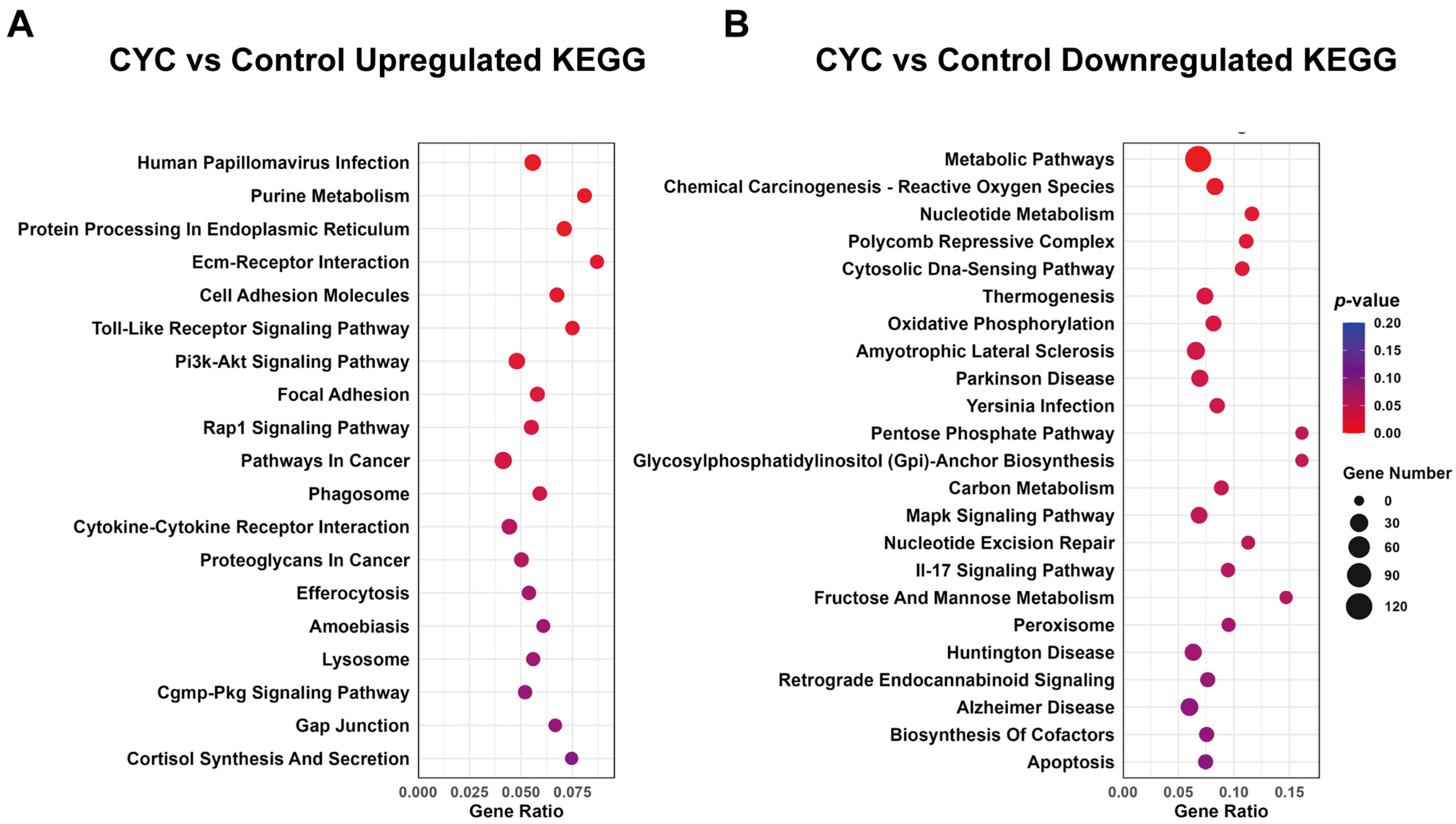

3.4.2. KEGG Enrichment Analysis of Functional Pathways for DEGs

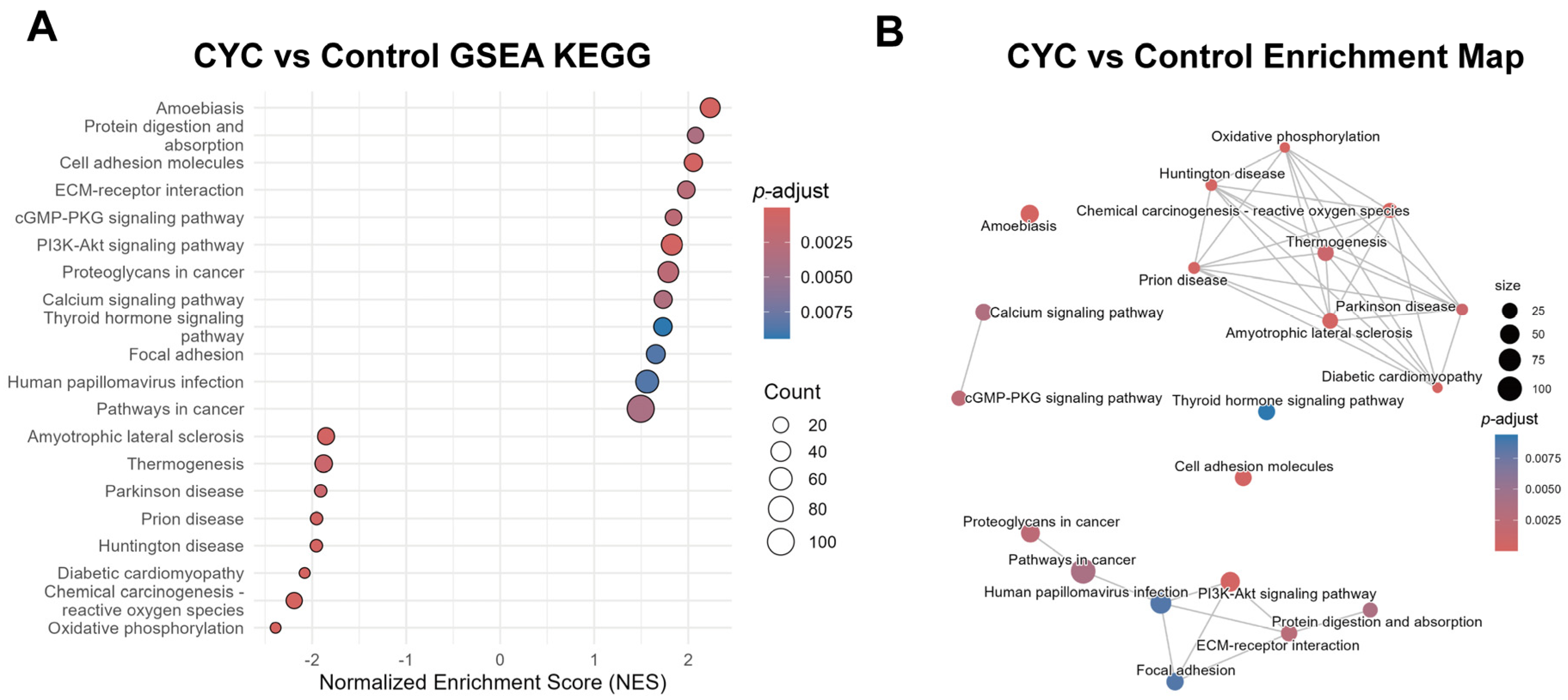

3.4.3. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis Verification of Systematic Enrichment Trends in Key Pathways

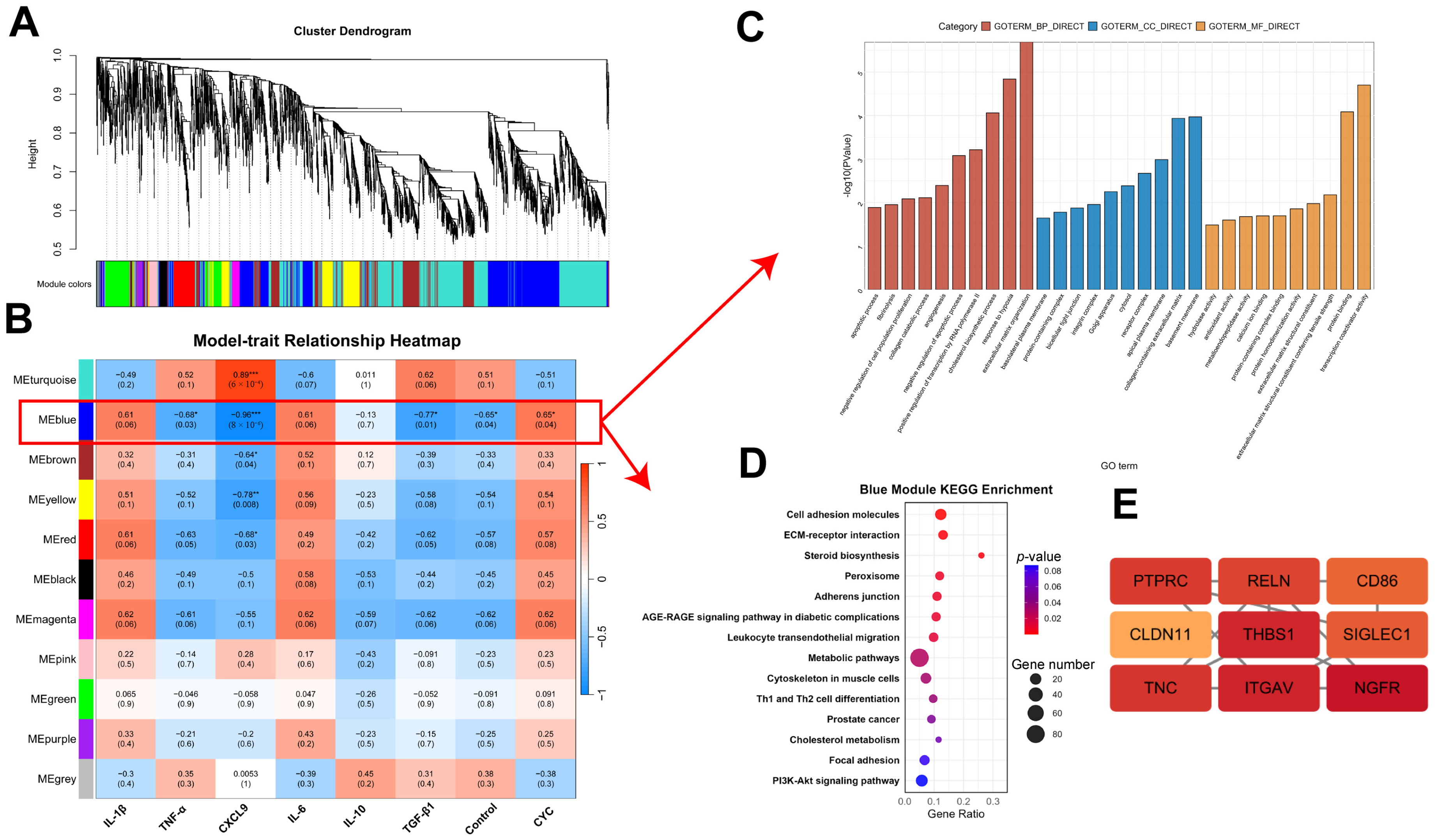

3.4.4. WGCNA of Host Transcriptome Correlation with Hepatic Inflammatory Factors

3.5. qRT-PCR Validation of Transcriptome Results

3.6. Western Blot Validation of PI3K-AKT and NF-κB Pathway Activation

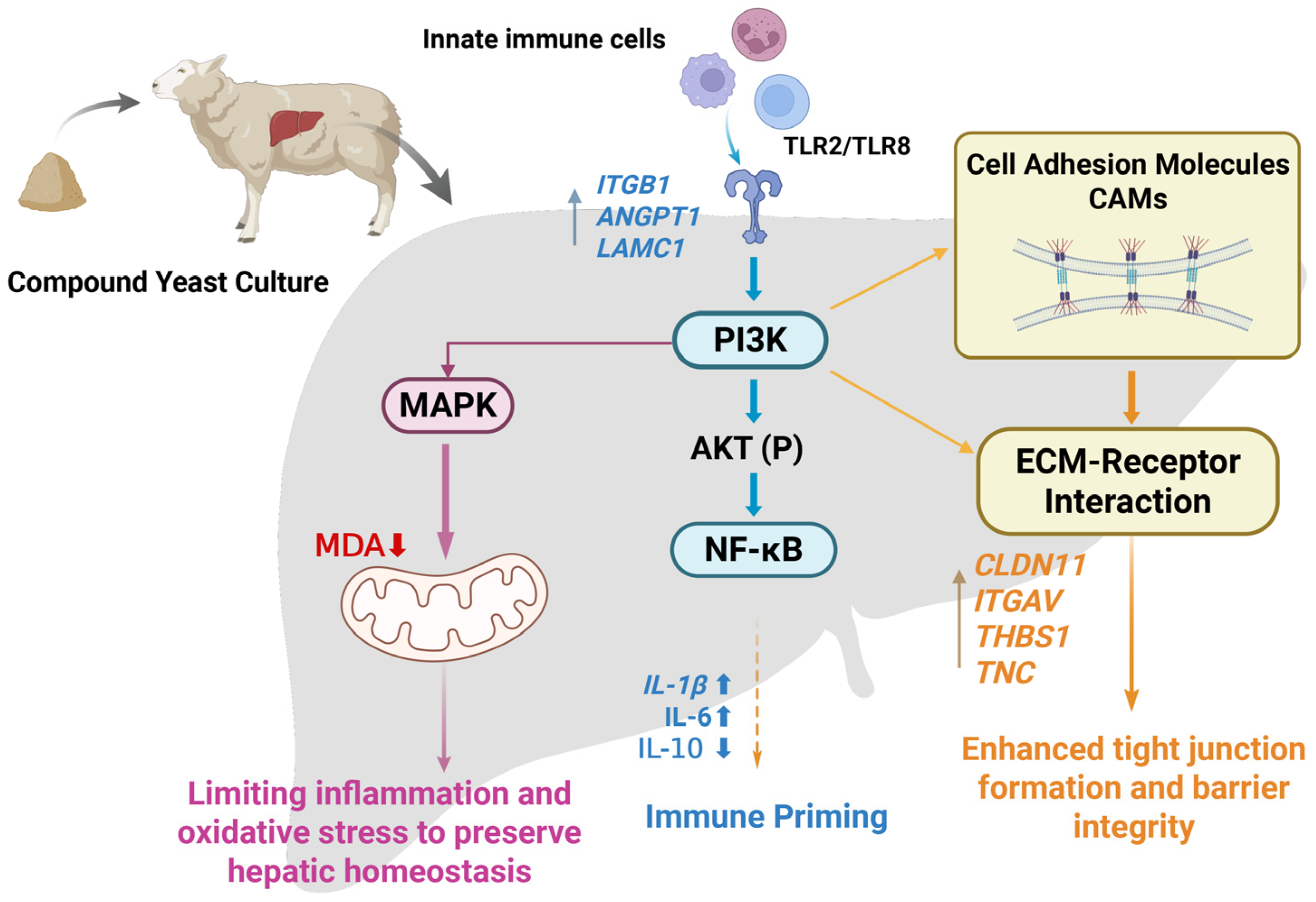

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CYC | compound yeast culture |

| WGCNA | Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis |

| GSEA | Gene Set Enrichment Analysis |

| PI3K-AKT | Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase–AKT |

| ECM–receptor | Extracellular matrix–receptor |

| TLRs | Toll-like receptors |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1 beta |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| IL-10 | Interleukin-10 |

| TNF-α | Tumour necrosis factor-alpha |

| TGF-β1 | Transforming growth factor-beta 1 |

| CXCL9 | C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 9 |

| PTPRC | Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase Receptor Type C (Hub Gene) |

| CD86 | Cluster of Differentiation 86 (Hub Gene) |

| ITGAV | Integrin Subunit Alpha V (Hub Gene) |

| CAMs | Cell Adhesion Molecules |

| TMR | Total mixed ration |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| qRT-PCR | quantitative reverse transcription (qRT)-PCR |

| H&E | Haematoxylin and eosin |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| DEGs | Differentially expressed genes |

| TPM | Transcripts per million |

| FDR | False discovery rate |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| 3D PCA | Three-dimensional principal component analysis |

| cGMP-PKG | Cyclic guanosine monophosphate–protein kinase G |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa B |

| PRRs | Pattern recognition receptors |

| PAMPs | Pathogen-associated molecular patterns |

| SEM | Standard Error of the Mean |

| T-SOD | Total superoxide dismutase |

| GSH-Px | Glutathione peroxidase |

| T-AOC | Total antioxidant capacity |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

References

- Mohapatra, A.; De, K.; Saxena, V.K.; Mallick, P.K.; Devi, I.; Singh, R. Behavioral and physiological adjustments by lambs in response to weaning stress. J. Vet. Behav. 2021, 41, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.; Giráldez, F.J.; Frutos, J.; Andrés, S. Liver transcriptomic and proteomic profiles of preweaning lambs are modified by milk replacer restriction. J. Dairy Sci. 2019, 102, 1194–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izuddin, W.I.; Humam, A.M.; Loh, T.C.; Foo, H.L.; Samsudin, A.A. Dietary Postbiotic Lactobacillus plantarum Improves Serum and Ruminal Antioxidant Activity and Upregulates Hepatic Antioxidant Enzymes and Ruminal Barrier Function in Post-Weaning Lambs. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, B.; Hong, Q.; Li, X.; Lu, M.; Zhou, J.; Yue, S.; Wang, Z.; Wang, L.; Peng, Q.; Xue, B. Hepatic injury induced by dietary energy level via lipid accumulation and changed metabolites in growing semi-fine wool sheep. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 745078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, L.D.; Eler, J.P.; Pereira, M.A.; Rosa, A.F.; Alexandre, P.A.; Moncau, C.T.; Salvato, F.; Rosa-Fernandes, L.; Palmisano, G.; Ferraz, J.B.S.; et al. Liver proteomics unravel the metabolic pathways related to Feed Efficiency in beef cattle. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohtaki, T.; Ogata, K.; Kajikawa, H.; Sumiyoshi, T.; Asano, S.; Tsumagari, S.; Horikita, T. Effect of high-concentrate corn grain diet-induced elevated ruminal lipopolysaccharide levels on dairy cow liver function. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2020, 82, 971–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, Q.; Qiu, X.; Gao, C.; Muhammad, A.U.R.; Cao, B.; Su, H. High-density diet improves growth performance and beef yield but affects negatively on serum metabolism and visceral morphology of holstein steers. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2020, 104, 1197–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, N.A.; Chethan, H.S.; Srivastava, R.; Gabbur, A.B. Role of probiotics in ruminant nutrition as natural modulators of health and productivity of animals in tropical countries: An overview. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2022, 54, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Yang, L.; Chen, H.; Liu, S.; Li, X.; Li, S.; Ying, C.; Li, X.; Du, R.; Liu, D. Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Kluyveromyces marxianus yeast co-cultures modulate the ruminal microbiome and metabolite availability to enhance rumen barrier function and growth performance in weaned lambs. Anim. Nutr. 2024, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Liu, S.; Li, S.; Li, D.; Li, X.; Xu, Z.; Liu, D. Effects of yeast culture on growth performance, immune function, antioxidant capacity and hormonal profile in mongolian ram lambs. Front. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 1424073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Ying, C.; Bai, P.; Demberel, S.; Tumenjargal, B.; Yang, L.; Liu, D. Microbial dynamics, metabolite profiles, and chemical composition in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Kluyveromyces marxianus co-culture during solid-state fermentation. Food Biosci. 2025, 64, 105849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; An, N.; Chen, H.; Liu, D. Effects of yeast culture on growth performance, antioxidant capacity, immune function, and intestinal microbiota structure in simmental beef cattle. Front. Vet. Sci. 2025, 11, 1533081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Yang, L.; Chen, H.; Bai, P.; Li, X.; Liu, D. Transcriptomic characterization of the functional and morphological development of the rumen wall in weaned lambs fed a diet containing yeast co-cultures of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Kluyveromyces marxianus. Front. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 1510689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yang, X.; Chen, H.; Liu, S.; Hao, P.; Ning, J.; Wu, Y.; Liang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, D. Yeast culture in weaned lamb feed: A proteomic journey into enhanced rumen health and growth. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2025, 16, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpinelli, N.A.; Halfen, J.; Michelotti, T.C.; Rosa, F.; Trevisi, E.; Chapman, J.D.; Sharman, E.S.; Osorio, J.S. Yeast culture supplementation effects on systemic and polymorphonuclear leukocytes’ mRNA biomarkers of inflammation and liver function in peripartal dairy cows. Animals 2023, 13, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Research Council (US). Nutrient Requirements of Small Ruminants; National Research Council (US), Committee on Nutrient Requirements of Small Ruminants: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, C.; Shi, C.; Liu, L.; Han, J.; Zhang, Y.; Du, G.; Yin, Y.; Zhao, J. Majorbio Cloud 2024: Update single-cell and multiomics workflows. Imeta 2024, 3, e217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. HISAT: A fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, J. fastp: An ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertea, M.; Pertea, G.M.; Antonescu, C.M.; Chang, T.-T.; Mendell, J.T.; Salzberg, S.L. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Dewey, C.N. RSEM: Accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinform. 2011, 12, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, S.S.; Wilk, M.B. An Analysis of Variance Test for Normality (Complete Samples). Biometrika 1965, 52, 591–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Hu, E.; Cai, Y.; Xie, Z.; Luo, X.; Zhan, L.; Tang, W.; Wang, Q.; Liu, B.; Wang, R.; et al. Using clusterProfiler to characterize multiomics data. Nat. Protoc. 2024, 19, 3292–3320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langfelder, P.; Horvath, S. WGCNA: An R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinform. 2008, 9, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shannon, P.; Markiel, O.; Ozier, O.; Baliga, N.; Wang, J.; Ramage, D.; Amin, N.; Schwikowski, B.; Ideker, T. Cytoscape: A software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003, 13, 2498–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, G.D.; Hogue, C.W.V. An automated method for finding molecular complexes in large protein interaction networks. BMC Bioinform. 2003, 4, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Wang, H. Ca2+-stimulated ADCY1 and ADCY8 regulate distinct aspects of synaptic and cognitive flexibility. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1215255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kircheis, R.; Planz, O. The role of toll-like receptors (TLRs) and their related signaling pathways in viral infection and inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilzer, M.; Roggel, F.; Gerbes, A.L. Role of Kupffer cells in host defense and liver disease. Liver Int. 2006, 26, 1175–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, B.; Raza, S.H.A.; Pant, S.D.; Gao, Z.; Zhang, F.; Wang, Z.; Hou, S.; Alkhateeb, M.A.; Al Abdulmonem, W.; Alharbi, Y.M.; et al. The impact of different levels of wheat diets on hepatic oxidative stress, immune response, and lipid metabolism in tibetan sheep (Ovis aries). BMC Vet. Res. 2024, 20, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Xue, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Meng, M.; Chang, G.; Shen, X. A high-concentrate diet provokes inflammatory responses by downregulating Forkhead box protein A2 (FOXA2) through epigenetic modifications in the liver of dairy cows. Gene 2022, 837, 146703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Huang, J.; Zhang, H.; Song, X.; Jiang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Shen, X. Live yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) improves growth performance and liver metabolic status of lactating Hu sheep. J. Dairy Sci. 2025, 108, 3700–3715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Feng, Y.; Gong, T.; Wu, D.; Zheng, X.; Luo, Y.; Yang, Y.; Song, Z.; Gong, L.; Zhang, G. Porcine enteric alphacoronavirus infection increases lipid droplet accumulation to facilitate the virus replication. J. Integr. Agric. 2024, 23, 988–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, I.; Paakinaho, V.; Baek, S.; Sung, M.H.; Hager, G.L. Synergistic gene expression during the acute phase response is characterized by transcription factor assisted loading. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Hwang, S.; Ahmed, Y.A.; Feng, D.; Li, N.; Ribeiro, M.; Lafdil, F.; Kisseleva, T.; Szabo, G.; Gao, B. Immunopathobiology and therapeutic targets related to cytokines in liver diseases. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2021, 18, 18–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Sun, H.; Tao, H.; Ding, Y.; Xue, S.; Fang, Y. Effects of yeast on inflammatory responses in yellow-feathered broilers induced by single and multiple lipopolysaccharide stimulation. R. Bras. Zootec. 2024, 53, e20230105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodridge, H.S.; Wolf, A.J.; Underhill, D.M. Beta-glucan recognition by the innate immune system. Immunol. Rev. 2009, 230, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiegs, G.; Horst, A.K. TNF in the liver: Targeting a central player in inflammation. Semin. Immunopathol. 2022, 44, 445–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedel, J.-H.; Robben, L.; Paust, H.-J.; Zhao, Y.; Asada, N.; Song, N.; Peters, A.; Kaffke, A.; Borchers, A.; Tiegs, G.; et al. Glucocorticoids target the CXCL9/CXCL10-CXCR3 axis and confer protection against immune-mediated kidney injury. JCI Insight 2023, 8, e160251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Geng, M.; Li, K.; Gao, H.; Jiao, X.; Ai, K.; Wei, X.; Yang, J. TGF-β1 suppresses the T-cell response in teleost fish by initiating Smad3- and Foxp3-mediated transcriptional networks. J. Biol. Chem. 2022, 299, 102843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W. TGF-β regulation of T cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2023, 41, 483–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Dan, J.; Meng, S.; Li, Y.; Li, J. TLR4 inhibited autophagy by modulating PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway in Gastric cancer cell lines. Gene 2023, 876, 147520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, M.; Bai, L.; Wei, H.; Guo, Y.; Sun, G.; Sun, H.; Shi, B. Dietary supplementation with pterostilbene activates the PI3K-AKT-mTOR signalling pathway to alleviate progressive oxidative stress and promote placental nutrient transport. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2024, 15, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahill, C.M.; Rogers, J.T. Interleukin (IL) 1β induction of IL-6 is mediated by a novel phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-dependent AKT/IκB kinase α pathway targeting activator protein-1. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 25900–25912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedro, A.R.V.; Lima, T.; Fróis-Martins, R.; Leal, B.; Ramos, I.C.; Martins, E.G.; Cabrita, A.R.J.; Fonseca, A.J.M.; Maia, M.R.G.; Vilanova, M.; et al. Dectin-1-mediated production of pro-inflammatory cytokines induced by yeast β-glucans in bovine monocytes. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 689879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Lan, W.; Ye, S.; Zhu, B.; Fu, Z. Transcriptomic Analyses Reveal the Protective Immune Regulation of Conjugated Linoleic Acids in Sheep Ruminal Epithelial Cells. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 588082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, G.; Gevezova, M.; Sarafian, V.; Maes, M. Redox regulation of the immune response. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2022, 19, 1079–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Wu, M.; Chen, K.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, R.; Huang, X. ROS-mediated M1 polarization-necroptosis crosstalk involved in di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate-induced chicken liver injury. Poult. Sci. 2025, 104, 104558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liang, H.; Xu, L.; Zou, B.; Zhang, T.; Xue, F.; Qu, M. Rumen fermentative metabolomic and blood insights into the effect of yeast culture supplement on growing bulls under heat stress conditions. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 947822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene Sequence Number | Gene Name | Primer Sequence (5′–3′) | Fragment Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| NM_001009465.2 | IL-1β | F: TGCTGGATAGCCCATGTGTG | 84 bp |

| R: CGAAGCTCATGCAGAACACC | |||

| NM_001009392.1 | IL-6 | F: TCATGGAGTTGCAGAGCAGT | 137 bp |

| R: TGCGTTCTTTACCCACTCGT | |||

| NM_001024860.1 | TNF-α | F: ATAACAAGCCGGTAGCCCAC | 82 bp |

| R: AGGGCATTCGCATACGAGTC | |||

| XM_004009924.5 | CXCL9 | F: GAGTTCAAGGAATCCCAGCAAT | 121 bp |

| R: TCACAAGTAGGGCTTGGAGC | |||

| NM_001190390.1 | GAPDH | F: CGGCACAGTCAAGGCAGAGAAC | 115 bp |

| R: CACGTACTCAGCACCAGCATCAC |

| Gene Sequence Number | Gene Name | Primer Sequence (5′–3′) | Fragment Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| NM_001139455.1 | MAPK13 | F: TCACCCGGAAAAAGGGCTTC | 88 bp |

| R: CCTATGTGCGTCAGGGACAC | |||

| XM_027969415.2 | JUND | F: GCTCAAGGATGAACCGCAGA | 98 bp |

| R: CCTTAATGCGCTCTTGCGTG | |||

| XM_004014883.5 | CEBPB | F: CCCGCCCGTGGTGTTATTT | 124 bp |

| R: ATCAACTTCGAAACCGGCCC | |||

| XM_060408446.1 | IKBKG | F: CTCACCCAAGGGAGGAGTGA | 80 bp |

| R: GATCGCCCTGTCGTACATCC | |||

| XM_060411578.1 | ATF4 | F: GGACGGCCATCGATTTTGTG | 113 bp |

| R: GATCGCCCTGTCGTACATCC | |||

| XM_042229308.1 | PTPRC | F: GGTCCTTCCACTCAAGACACCT | 89 bp |

| R: GCTGTTGTGGTGAGACTGTGTG | |||

| XM_027974687.2 | NGFR | F: TAGCATGAACAAGCCCCGAG | 122 bp |

| R: TCAGGTCAAAGAAGTGCGGT | |||

| XM_042242806.2 | TNC | F: CAGGAACCCAGAGGAAGCTG | 82 bp |

| R: CCTTGGGTGAAGCCAGAGAC | |||

| NM_001190390.1 | GAPDH | F: CGGCACAGTCAAGGCAGAGAAC | 115 bp |

| R: CACGTACTCAGCACCAGCATCAC |

| Sample | Raw Reads | Clean Reads | Clean Bases | Error Rate (%) | Phred > 20 Q20 (%) | Phred > 30 Q30 (%) | GC Content (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Con1 | 40,795,574 | 40,415,582 | 6,007,157,449 | 0.0122 | 98.61 | 95.71 | 42.55 |

| Con2 | 45,443,212 | 44,989,736 | 6,706,481,259 | 0.0123 | 98.53 | 95.42 | 48.49 |

| Con3 | 41,117,388 | 40,759,796 | 6,064,085,751 | 0.0121 | 98.66 | 95.88 | 42.43 |

| Con4 | 44,108,830 | 43,730,030 | 6,501,297,594 | 0.0121 | 98.63 | 95.77 | 45.85 |

| Con5 | 51,050,188 | 50,569,256 | 7,532,453,630 | 0.0122 | 98.58 | 95.60 | 49.09 |

| CYC1 | 47,973,624 | 47,536,592 | 7,094,922,014 | 0.0122 | 98.58 | 95.61 | 47.13 |

| CYC2 | 46,513,486 | 46,084,096 | 6,859,413,840 | 0.0122 | 98.6 | 95.65 | 47.44 |

| CYC3 | 45,482,228 | 45,067,310 | 6,725,812,139 | 0.0122 | 98.59 | 95.62 | 47.40 |

| CYC4 | 43,768,544 | 43,324,786 | 6,463,150,497 | 0.0123 | 98.57 | 95.57 | 48.42 |

| CYC5 | 50,995,150 | 50,530,560 | 7,547,720,177 | 0.0122 | 98.61 | 95.69 | 47.33 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, C.; Bai, H.; Bai, P.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Y.; Liu, D.; Chen, H. Immune-Modulatory Mechanism of Compound Yeast Culture in the Liver of Weaned Lambs. Animals 2026, 16, 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010104

Li C, Bai H, Bai P, Zhang C, Wang Y, Liu D, Chen H. Immune-Modulatory Mechanism of Compound Yeast Culture in the Liver of Weaned Lambs. Animals. 2026; 16(1):104. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010104

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Chenlu, Hui Bai, Pengxiang Bai, Chenxue Zhang, Yuan Wang, Dacheng Liu, and Hui Chen. 2026. "Immune-Modulatory Mechanism of Compound Yeast Culture in the Liver of Weaned Lambs" Animals 16, no. 1: 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010104

APA StyleLi, C., Bai, H., Bai, P., Zhang, C., Wang, Y., Liu, D., & Chen, H. (2026). Immune-Modulatory Mechanism of Compound Yeast Culture in the Liver of Weaned Lambs. Animals, 16(1), 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010104