Group and Individual Changes in Spinal Mobility During a 12-Week Rehabilitation Program Including Swimming in Horses with Axial Musculoskeletal Lesions

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals Included in the Study

2.2. Grouping Based on Lesion Location

2.3. Training Protocol

2.4. Data Acquisition

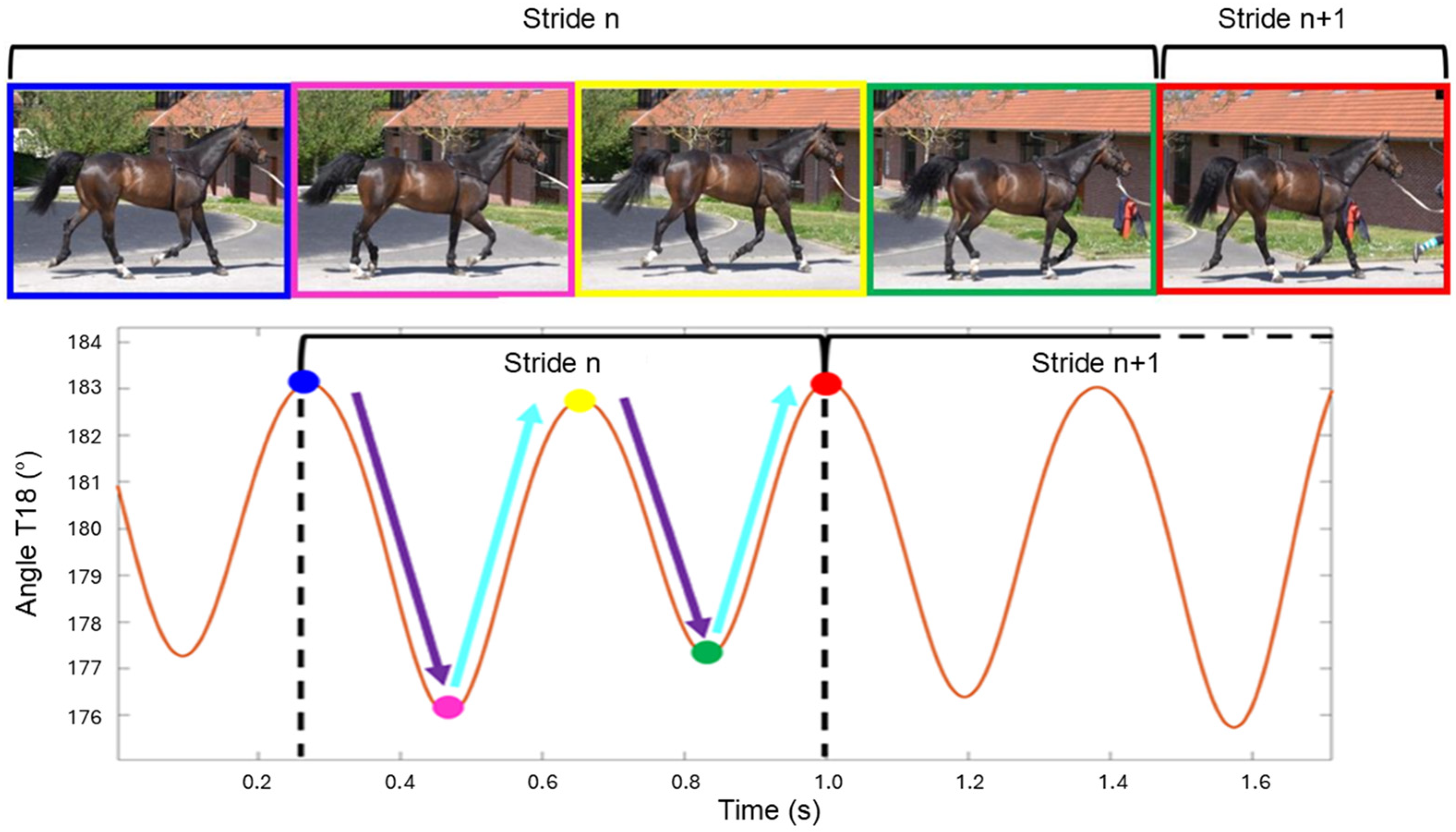

2.5. Data Processing

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis of the Dataset

3.2. Group Changes in Thoracolumbar Mobility Across Training Phases

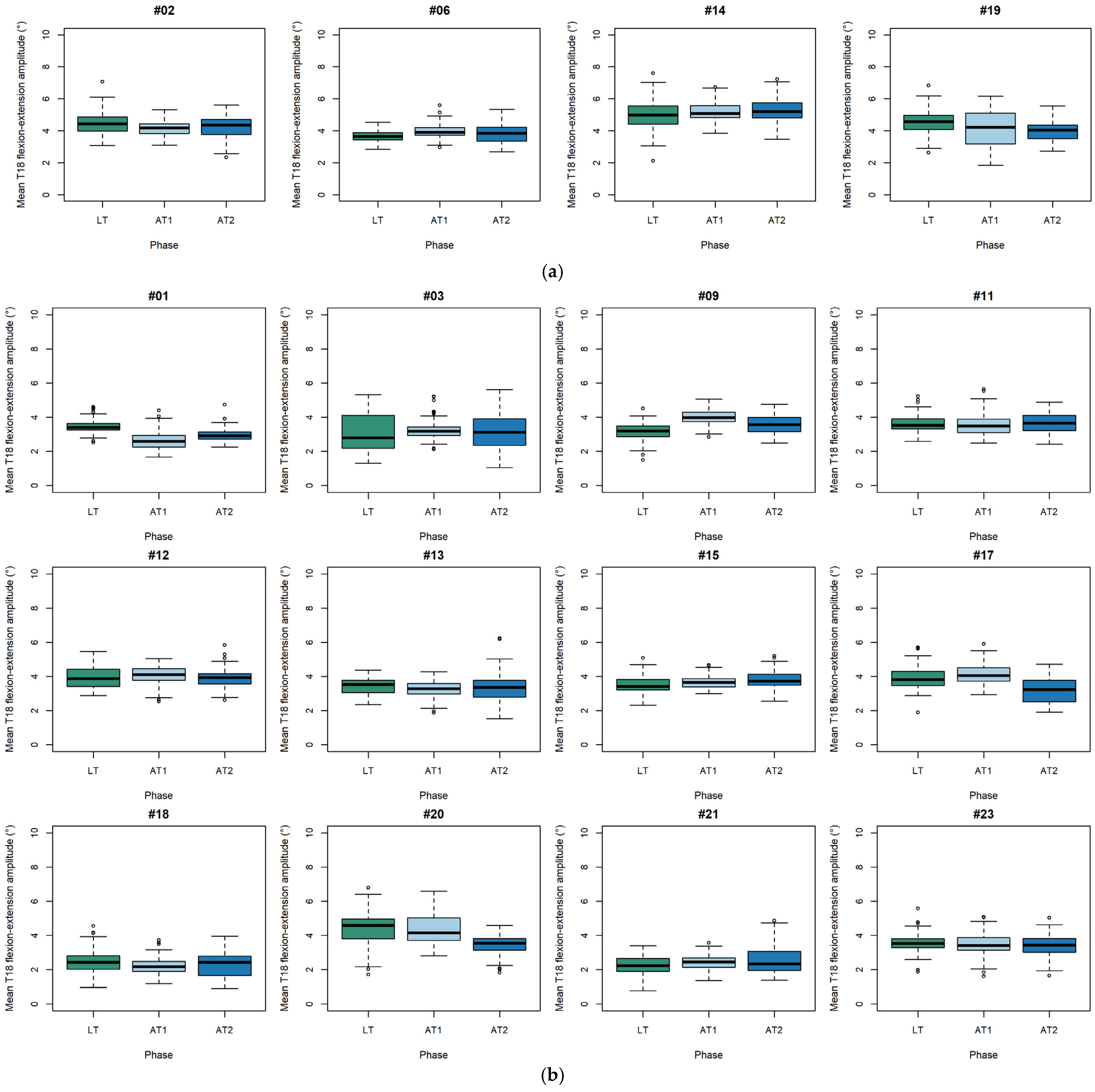

3.3. Individual Changes in Thoracolumbar Mobility Across Training Phases in Horses with Cervical Lesions

3.4. Individual Changes in Thoracolumbar Mobility Across Training Phases in Horses with Thoracolumbar Lesions

4. Discussion

4.1. Group-Level Findings and Biomechanical Interpretation

4.2. Within-Group Changes over Time and Temporal Patterns

4.3. Individual Variability and Clinical Relevance

4.4. Methodological Considerations

4.5. Clinical Implications and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MOCAP | motion capture |

| IMU | inertial measurement unit |

| AP-SIVJ | articular processes-synovial intervertebral joints |

| LT | land training |

| AT1 | Aquatic Training 1 |

| AT2 | Aquatic Training 2 |

| ROM | range of motion |

| LME | linear mixed-effects |

| Min | minute |

| km/h | kilometers per hour |

| Std/s | stride/s |

| Std-Freq | stride frequency |

| EMG | electromyography |

Appendix A

| Horse ID | SI_up Withers (Mean ± SD) | SI_up Pelvis (Mean ± SD) |

| Cervical group (n = 4) | ||

| #02 | 11.5 ± 15.6 | 2.5 ± 12.5 |

| #06 | 6.1 ± 12.6 | 9.2 ± 14.6 |

| #14 | 1.1 ± 12.2 | 5.6 ± 17.8 |

| #19 | 0.5 ± 13.5 | 20.0 ± 14.7 |

| Mean ± SD | 4.8 ± 13.7 | 9.3 ± 16.1 |

| Thoracolumbar group (n = 4) | ||

| #01 | 7.8 ± 16.3 | 3.0 ± 14.7 |

| #03 | 15.8 ± 10.5 | 7.3 ± 12.4 |

| #09 | 12.4 ± 14.6 | 10.1 ± 18.1 |

| #11 | 18.5 ± 9.3 | 1.4 ± 10.1 |

| #12 | 11.9 ± 13.8 | 30.9 ± 11.5 |

| #13 | 6.0 ± 13.0 | 2.0 ± 12.6 |

| #15 | 11.1 ± 10.0 | 7.0 ± 13.4 |

| #17 | 6.3 ± 11.0 | 3.4 ± 10.9 |

| #18 | 6.3 ± 18.0 | 7.9 ± 14.2 |

| #20 | 13.9 ± 15.3 | 10.1 ± 13.2 |

| #21 | 5.3 ± 15.5 | 2.2 ± 18.1 |

| #23 | 26.0 ± 8.9 | 6.1 ± 16.3 |

| Mean ± SD | 11.2 ± 13.3 | 7.7 ± 14.0 |

| All horses (n = 16) | ||

| Mean ± SD | 10.0 ± 13.1 | 8.0 ± 14.1 |

Appendix B

| Horse | Phase | Week | Stride Frequency | ||||||

| Mean Square | F-Value | p-Value | Mean Square | F-Value | p-Value | Mean Square | F-Value | p-Value | |

| Cervical group (n = 4) | |||||||||

| #02 | 6.73 | 9.63 | <0.001 | 0.46 | 1.33 | 0.250 | 4.52 | 12.95 | <0.001 |

| #06 | 8.53 | 28.47 | <0.001 | 9.74 | 65.00 | <0.001 | 7.87 | 52.52 | <0.001 |

| #14 | 10.82 | 17.92 | <0.001 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.750 | 64.97 | 215.23 | <0.001 |

| #19 | 15.53 | 13.43 | <0.001 | 46.06 | 79.67 | <0.001 | 4.25 | 7.35 | 0.007 |

| Mean | 1.96 | 2.39 | 0.092 | 22.16 | 54.13 | <0.001 | 57.47 | 140.38 | <0.001 |

| Thoracolumbar group (n = 12) | |||||||||

| #01 | 31.97 | 134.17 | <0.001 | 1.76 | 14.80 | <0.001 | 18.09 | 151.79 | <0.001 |

| #03 | 1.89 | 2.30 | 0.102 | 1.09 | 2.63 | 0.101 | 123.55 | 299.71 | <0.001 |

| #09 | 37.42 | 92.03 | <0.001 | 0.04 | 0.18 | 0.673 | 5.13 | 25.22 | <0.001 |

| #11 | 0.56 | 1.09 | 0.338 | 0.19 | 0.74 | 0.392 | 12.65 | 49.17 | <0.001 |

| #12 | 0.81 | 1.77 | 0.172 | 29.76 | 129.94 | <0.001 | 3.48 | 15.20 | <0.001 |

| #13 | 0.64 | 1.01 | 0.366 | 6.85 | 21.58 | <0.001 | 3.65 | 11.48 | <0.001 |

| #15 | 0.92 | 3.82 | 0.023 | 0.77 | 6.44 | 0.012 | 33.90 | 282.57 | <0.001 |

| #17 | 40.44 | 50.39 | <0.001 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.936 | 8.58 | 21.37 | <0.001 |

| #18 | 4.80 | 7.22 | <0.001 | 3.09 | 9.29 | 0.003 | 0.17 | 0.52 | 0.472 |

| #20 | 55.88 | 60.13 | <0.001 | 47.21 | 101.59 | <0.001 | 27.10 | 58.33 | <0.001 |

| #21 | 4.64 | 5.50 | 0.004 | 1.83 | 4.34 | 38 | 4.48 | 10.62 | 0.001 |

| #23 | 0.32 | 0.69 | 0.500 | 0.20 | 0.89 | 0.347 | 4.89 | 21.47 | <0.001 |

| Mean | 10.12 | 13.61 | <0.001 | 15.04 | 40.42 | <0.001 | 229.43 | 616.67 | <0.001 |

Appendix C

References

- Lam, K.H.; Parkin, T.D.H.; Riggs, C.M.; Morgan, K.L. Descriptive analysis of retirement of Thoroughbred racehorses due to tendon injuries at the Hong Kong Jockey Club (1992–2004). Equine Vet. J. 2007, 39, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munsters, C.C.B.M.; van den Broek, J.; Welling, E.; van Weeren, R.; van Oldruitenborgh-Oosterbaan, M.M.S. A prospective study on a cohort of horses and ponies selected for participation in the European Eventing Championship: Reasons for withdrawal and predictive value of fitness tests. BMC Vet. Res. 2013, 9, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrestha, K.; Gilkerson, J.R.; Stevenson, M.A.; Flash, M.L. Drivers of exit and outcomes for Thoroughbred racehorses participating in the 2017–2018 Australian racing season. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0257581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaneps, A.J. Practical Rehabilitation and Physical Therapy for the General Equine Practitioner. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Equine Pract. 2016, 32, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atalaia, T.; Prazeres, J.; Abrantes, J.; Clayton, H.M. Equine Rehabilitation: A Scoping Review of the Literature. Animals 2021, 11, 1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irwin, D.H.G.; Howell, D.W. Some thoughts on swimming horses in a pool. J. S. Afr. Vet. Assoc. 1980, 51, 189–191. [Google Scholar]

- Murakami, M.; Imahara, T.; Inui, T.; Amada, A.; Senta, T.; Takagi, S.; Kubo, K.; Sugimoto, O.; Watanabe, H.; Ikeda, S.; et al. Swimming Exercises in Horses. Exp. Rep. Equine Health Lab. 1976, 1976, 27–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santosuosso, E.; Leguillette, R.; Vinardell, T.; Filho, S.; Massie, S.; McCrae, P.; Johnson, S.; Rolian, C.; David, F. Kinematic Analysis During Straight Line Free Swimming in Horses: Part 1—Forelimbs. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 752375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A. Healing Waters? In Horse Report—School of Veterinary Medicine—University of California. 2022. Available online: https://cehhorsereport.vetmed.ucdavis.edu/news/healing-waters (accessed on 25 December 2025).

- Gaulmin, P.; Marin, F.; Moiroud, C.; Beaumont, A.; Jacquet, S.; De Azevedo, E.; Martin, P.; Audigié, F.; Chateau, H.; Giraudet, C. Description and Analysis of Horse Swimming Strategies in a U-Shaped Pool. Animals 2025, 15, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraudet, C.; Moiroud, C.; Beaumont, A.; Gaulmin, P.; Hatrisse, C.; Azevedo, E.; Denoix, J.-M.; Ben Mansour, K.; Martin, P.; Audigié, F.; et al. Development of a Methodology for Low-Cost 3D Underwater Motion Capture: Application to the Biomechanics of Horse Swimming. Sensors 2023, 23, 8832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, M.R. Principles and Application of Hydrotherapy for Equine Athletes. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Equine Pract. 2016, 32, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokuriki, M.; Ohtsuki, R.; Kal, M.; Hiraga, A.; Oki, H.; Miyahara, Y.; Aoki, O. EMG activity of the muscles of the neck and forelimbs during different forms of locomotion. Equine Vet. J. Suppl. 1999, 30, 231–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M. Equine Rehabilitation Therapy for Joint Disease. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Equine Pract. 2005, 21, 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamioka, H.; Tsutani, K.; Okuizumi, H.; Mutoh, Y.; Ohta, M.; Handa, S.; Okada, S.; Kitayuguchi, J.; Kamada, M.; Shiozawa, N.; et al. Effectiveness of aquatic exercise and balneotherapy: A summary of systematic reviews based on randomized controlled trials of water immersion therapies. J. Epidemiol. 2010, 20, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, A.; Saitua, A.; Becero, M.; Riber, C.; Satué, K.; de Medina, A.S.; Argüelles, D.; Castejón-Riber, C. The Use of the Water Treadmill for the Rehabilitation of Musculoskeletal Injuries in the Sport Horse. J. Vet. Res. 2019, 63, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klomp, M. Swimming exercise and race performance in Thoroughbred racehorses. Pferdeheilkunde Equine Med. 2014, 30, 403–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misumi, K.; Sakamoto, H.; Shimizu, R. The validity of swimming training for two-year-old thoroughbreds. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 1994, 56, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coudry, V.; Thibaud, D.; Riccio, B.; Audigié, F.; Didierlaurent, D.; Denoix, J.-M. Efficacy of tiludronate in the treatment of horses with signs of pain associated with osteoarthritic lesions of the thoracolumbar vertebral column. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2007, 68, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maldonado, M.D.; Parkinson, S.D.; Story, M.R.; Haussler, K.K. The Effect of Chiropractic Treatment on Limb Lameness and Concurrent Axial Skeleton Pain and Dysfunction in Horses. Animals 2022, 12, 2845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geiger, T.; Lindenhahn, L.; Delarocque, J.; Geburek, F. Evaluation of water treadmill training, lunging and treadmill training in the rehabilitation of horses with back pain. BMC Vet. Res. 2025, 21, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egenvall, A.; Engström, H.; Byström, A. Back motion in unridden horses in walk, trot and canter on a circle. Vet. Res. Commun. 2023, 47, 1831–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardeman, A.M.; Byström, A.; Roepstorff, L.; Swagemakers, J.H.; Van Weeren, P.R.; Bragança, F.M.S. Range of motion and between-measurement variation of spinal kinematics in sound horses at trot on the straight line and on the lunge. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0222822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatrisse, C.; Macaire, C.; Hebert, C.; Hanne-Poujade, S.; De Azevedo, E.; Audigié, F.; Ben Mansour, K.; Marin, F.; Martin, P.; Mezghani, N.; et al. A Method for Quantifying Back Flexion/Extension from Three Inertial Measurement Units Mounted on a Horse’s Withers, Thoracolumbar Region, and Pelvis. Sensors 2023, 23, 9625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKechnie-Guire, R.; Pfau, T. Differential Rotational Movement of the Thoracolumbosacral Spine in High-Level Dressage Horses Ridden in a Straight Line, in Sitting Trot and Seated Canter Compared to In-Hand Trot. Animals 2021, 11, 888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audigie, F.; Coudry, V.; Jacquet, S.; Poupot, M.; Denoix, J.-M. Diagnostic par imagerie des lésions de la région thoracolombaire chez le cheval. Bull. Acad. Vet. Fr. 2013, 166, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MATLAB, MathWorks Help Center. MATLAB Documentation. Available online: https://www.mathworks.com/help/matlab/index.html (accessed on 25 December 2025).

- Pinheiro, J.; Bates, D. Mixed-Effects Models in S and S-PLUS. In Statistics and Computing; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 101–110. [Google Scholar]

- Jaccard, J.; Becker, M.A.; Wood, G. Pairwise multiple comparison procedures: A review. Psychol. Bull. 1984, 96, 589–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. A power primer. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 112, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 25 December 2025).

- Kuznetsova, A.; Brockhoff, P.B.; Christensen, R.H.B. lmerTest Package: Tests in Linear Mixed Effects Models. J. Stat. Softw. 2017, 82, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez Álvarez, C.B.G.; Rhodin, M.; Bobbert, M.F.; Meyer, H.; Weishaupt, M.A.; Johnston, C.; Weeren, P.R. The effect of head and neck position on the thoracolumbar kinematics in the unridden horse. Equine Vet. J. 2006, 38, 445–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodin, M.; Johnston, C.; Holm, K.R.; Wennerstrand, J.; Drevemo, S. The influence of head and neck position on kinematics of the back in riding horses at the walk and trot. Equine Vet. J. 2005, 37, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wennerstrand, J.; Johnston, C.; Roethlisberger-Holm, K.; Erichsen, C.; Eksell, P.; Drevemo, S. Kinematic evaluation of the back in the sport horse with back pain. Equine Vet. J. 2004, 36, 707–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licka, T.F.; Peham, C.; Frey, R. Electromyographic activity of the longissimus dorsi muscles in horses during trotting on a treadmill. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2004, 65, 155–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.M. Electromyography in the horse: A useful technology? J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2018, 60, 43–58.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabor, G.; Williams, J.M. Equine rehabilitation: A review of trunk and hind limb muscle activity and exercise selection. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2018, 60, 97–103.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faber, M.; Johnston, C.; van Weeren, P.R.; Barneveld, A. Repeatability of back kinematics in horses during treadmill locomotion. Equine Vet. J. 2002, 34, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greve, L.; Pfau, T.; Dyson, S. Thoracolumbar movement in sound horses trotting in straight lines in hand and on the lunge and the relationship with hind limb symmetry or asymmetry. Vet. J. 2017, 220, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Horse | Sex | Breed | Discipline | Age (y) | Height (cm) | Body Mass (kg) | Main Lesions (Location) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cervical Group (n = 4) | |||||||

| #02 | Mare | SF | SJ | 14 | 160 | 502 | OA AP-SIVJ (C5–T1) |

| #06 | Gelding | SF | Eventing | 10 | 166 | 566 | Vertebral symphysis abnormality (C6–C7), OA AP-SIVJ (C6–T1), R1 hypogenesia |

| #14 | Gelding | SF | SJ | 9 | 177 | 596 | OA AP-SIVJ (C6–C7), vertebral symphysis abnormality (C6–T1) |

| #19 | Gelding | SF | SJ | 5 | 163 | 528 | OA AP-SIVJ (C6–C7), vertebral symphysis abnormality (C6–C7) |

| Thoracolumbar Group (n = 12) | |||||||

| #01 | Mare | SF | SJ | 11 | 164 | 504 | OA AP-SIVJ (T15–T16), DSP impingement (T13–T14, T16–T17) |

| #03 | Gelding | PFS | SJ | 12 | 148 | 424 | OA AP-SIVJ (T15–T16, T18–L1 > L1–L4), DSP impingement (T15–T18) |

| #09 | Gelding | SF | SJ | 11 | 170 | 618 | Vertebral body dysplasia (T9–T10 cuneiformis vertebrae), curvature abnormality (thoracic lordosis), DSP impingement (T12–T16) |

| #11 | Gelding | SF | SJ | 13 | 166 | 594 | OA AP-SIVJ (T14–T18), DSP impingement (T13–T17) |

| #12 | Gelding | SF | SJ | 11 | 170 | 520 | DSP impingement (T13–T18), OA AP-SIVJ (T14–T17) |

| #13 | Gelding | SF | SJ | 10 | 177 | 562 | OA AP-SIVJ (L1–L3) |

| #15 | Mare | SF | SJ | 8 | 166 | 560 | OA AP-SIVJ (T18–L2), curvature abnormality (lumbar kyphosis + scoliosis) |

| #17 | Gelding | SF | SJ | 9 | 180 | 616 | Vertebral symphysis abnormality (L6–S1) |

| #18 | Gelding | SF | SJ | 5 | 167 | 580 | Curvature abnormality (thoracolumbar lordo-kiphosis + lumbar scoliosis), OA AP-SIVJ (T15–T18) |

| #20 | Gelding | SF | SJ | 5 | 167 | 550 | OA AP-SIVJ (T15–L2), DSP impingement (T18–L1) |

| #21 | Mare | SF | SJ | 8 | 166 | 524 | Ventral spondylosis (T12–T13), DSP impingement (T14–L2), OA AP-SIVJ (T15–T16) |

| #23 | Mare | Z | SJ | 9 | 168 | 564 | Ventral spondylosis (T11–T12) |

| Day | Phase 1—Land Training (4 Weeks) | Phase 2—Aquatic Training (8 Weeks) |

|---|---|---|

| Monday | Walker (40 min) + flatwork (15 min walk, 4 min slow canter, 30 min flatwork at 3 gaits) | Walker (40 min) + swimming (see Table 3) |

| Tuesday | Walker (40 min) + gymnastic-cavaletti (15 min walk, 4 min slow canter, 30 min work at 3 gaits with cavaletti <50 cm) | Walker (40 min) + gymnastic-cavaletti (same as Phase 1) |

| Wednesday | Walker (40 min) + gallop (15 min walk, 4 min slow canter, 2 min walk, 3 × 3 min gallop + 2 min trot) | Walker (40 min) + swimming (see Table 3) |

| Thursday | Walker (40 min) + jumping (15 min walk, 4 min slow canter, 30 min work at 3 gaits with jumping: 20–25 jumps approx. 1 m) | Walker (40 min) + jumping (same as Phase 1) |

| Friday | Walker (40 min) + flatwork (5 min walk, 4 min slow canter, 30 min flatwork at 3 gaits) | Walker (40 min) + swimming (see Table 3) |

| Saturday | Walker (30 min) + lunge work (2 min walk, 4 min slow canter, 2 min slow trot, 2 min medium trot, 3 min medium canter, 1 min walk, 3 min medium canter, 3 min medium trot, 5 min walk) | Walker (30 min) + lunge work (same as Phase 1) |

| Sunday | Rest day + walker (30 min) | Rest day + walker (30 min) |

| Phase | Week | Monday | Wednesday | Friday | Total Weekly Distance (m) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distance Swum (m) | Session Duration (min) | Distance Swum (m) | Session Duration (min) | Distance Swum (m) | Session Duration (min) | |||

| Aquatic training 1 | W5 | 240 | 10 | 330 | 12 | 330 | 12 | 900 |

| W6 | 440 | 22 | 440 | 22 | 440 | 22 | 1320 | |

| W7 | 605 | 28 | 550 | 23 | 715 | 31 | 1870 | |

| W8 | 605 | 28 | 660 | 27 | 770 | 32 | 2035 | |

| Aquatic training 2 | W9 | 660 | 27 | 605 | 28 | 770 | 32 | 2035 |

| W10 | 770 | 32 | 660 | 27 | 935 | 36 | 2365 | |

| W11 | 770 | 32 | 660 | 27 | 935 | 36 | 2365 | |

| W12 | 770 | 32 | 605 | 28 | - | - | 1375 | |

| Horse ID | LT | AT1 | AT2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROM (°) | Std-Freq (std/s) | ROM (°) | Std-Freq (std/s) | ROM (°) | Std-Freq (std/s) | |

| Cervical group (n = 4) | ||||||

| #02 | 4.5 ± 0.7 | 1.42 ± 0.06 | 4.1 ± 0.5 | 1.42 ± 0.05 | 4.2 ± 0.7 | 1.39 ± 0.04 |

| #06 | 3.7 ± 0.4 | 1.42 ± 0.05 | 4.0 ± 0.4 | 1.45 ± 0.05 | 3.8 ± 0.6 | 1.43 ± 0.05 |

| #14 | 5.0 ± 0.9 | 1.27 ± 0.09 | 5.2 ± 0.5 | 1.27 ± 0.03 | 5.3 ± 0.7 | 1.30 ± 0.12 |

| #19 | 4.5 ± 0.7 | 1.36 ± 0.25 | 4.2 ± 1.1 | 1.41 ± 0.06 | 4.0 ± 0.6 | 1.38 ± 0.06 |

| Group mean | 4.4 ± 0.8 | 1.37 ± 0.14 | 4.4 ± 0.9 | 1.39 ± 0.08 | 4.3 ± 0.8 | 1.38 ± 0.08 |

| Thoracolumbar group (n = 12) | ||||||

| #01 | 3.5 ± 0.4 | 1.37 ± 0.06 | 2.6 ± 0.5 | 1.41 ± 0.06 | 3.0 ± 0.3 | 1.39 ± 0.05 |

| #03 | 3.0 ± 1.0 | 1.47 ± 0.07 | 3.2 ± 0.5 | 1.46 ± 0.06 | 3.1 ± 0.9 | 1.49 ± 0.11 |

| #09 | 3.2 ± 0.5 | 1.37 ± 0.05 | 4.0 ± 0.4 | 1.35 ± 0.05 | 3.6 ± 0.5 | 1.35 ± 0.05 |

| #11 | 3.6 ± 0.5 | 1.29 ± 0.05 | 3.6 ± 0.6 | 1.29 ± 0.05 | 3.7 ± 0.6 | 1.29 ± 0.05 |

| #12 | 3.9 ± 0.6 | 1.43 ± 0.06 | 4.1 ± 0.5 | 1.40 ± 0.04 | 3.9 ± 0.5 | 1.41 ± 0.05 |

| #13 | 3.4 ± 0.5 | 1.30 ± 0.04 | 3.3 ± 0.4 | 1.31 ± 0.06 | 3.4 ± 0.8 | 1.30 ± 0.05 |

| #15 | 3.5 ± 0.5 | 1.36 ± 0.06 | 3.7 ± 0.4 | 1.33 ± 0.04 | 3.8 ± 0.5 | 1.32 ± 0.06 |

| #17 | 3.9 ± 0.6 | 1.32 ± 0.05 | 4.1 ± 0.6 | 1.34 ± 0.05 | 3.2 ± 0.7 | 1.38 ± 0.05 |

| #18 | 2.5 ± 0.6 | 1.28 ± 0.10 | 2.2 ± 0.5 | 1.32 ± 0.07 | 2.3 ± 0.7 | 1.37 ± 0.13 |

| #20 | 4.4 ± 1.0 | 1.36 ± 0.08 | 4.4 ± 0.8 | 1.37 ± 0.11 | 3.4 ± 0.6 | 1.38 ± 0.14 |

| #21 | 2.2 ± 0.6 | 1.40 ± 0.08 | 2.4 ± 0.5 | 1.40 ± 0.06 | 2.5 ± 0.9 | 1.38 ± 0.06 |

| #23 | 3.5 ± 0.5 | 1.45 ± 0.06 | 3.5 ± 0.6 | 1.45 ± 0.06 | 3.4 ± 0.6 | 1.49 ± 0.09 |

| Group mean | 3.4 ± 0.9 | 1.37 ± 0.09 | 3.4 ± 0.8 | 1.37 ± 0.08 | 3.3 ± 0.8 | 1.39 ± 0.10 |

| Horse | Δ AT1-LT (°) | Δ AT2-AT1 (°) | Δ AT2-LT (°) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type III ANOVA | Estimate (°) (% evol) | TK | C’s d | Estimate (°) (% evol) | TK | C’s d | Estimate (°) (% evol) | TK | C’s d | |

| Cervical group (n = 4) | ||||||||||

| #02 | <0.001 | −0.3 (−7%) | 0.001 | 0.5 | 0 (0%) | 0.963 | - | −0.3 (−7%) | <0.001 | 0.3 |

| #06 | <0.001 | 0.4 (11%) | <0.001 | 0.8 | −0.2 (−5%) | <.001 | 0.4 | 0.1 (3%) | 0.027 | 0.3 |

| #14 | <0.001 | 0.3 (6%) | 0.001 | 0.3 | 0.2 (4%) | 0.0320 | 0.1 | 0.5 (10%) | <0.001 | 0.4 |

| #19 | <0.001 | −0.3 (−7%) | 0.126 | −0.4 (−10%) | <0.001 | 0.2 | −0.7 (−16%) | <0.001 | 0.8 | |

| Mean | 0.092 | 0.1 (2%) | - | - | −0.1 (−2%) | - | - | 0 (0%) | - | - |

| Thoracolumbar group (n = 12) | ||||||||||

| #01 | <0.001 | −0.7 (−20%) | <0.001 | 1.9 | 0.3 (12%) | <0.001 | 0.8 | −0.5 (−14%) | <0.001 | 1.4 |

| #03 | 0.102 | 0.1 (3%) | - | - | 0 (0%) | - | - | 0.2 (6%) | - | - |

| #09 | <0.001 | 0.8 (25%) | <0.001 | 1.8 | −0.4 (−10%) | <0.001 | 1 | 0.3 (9%) | <0.001 | 0.8 |

| #11 | 0.338 | −0.1 (−3%) | - | - | 0.1 (3%) | - | - | 0 (0%) | - | - |

| #12 | 0.172 | 0.1 (3%) | - | - | −0.1 (−2%) | - | - | 0 (0%) | - | - |

| #13 | 0.366 | −0.1 (−3%) | - | - | 0.1 (3%) | - | - | 0 (0%) | - | - |

| #15 | 0.023 | 0.1 (3%) | 0.418 | - | 0.1 (3%) | 0.267 | - | 0.1 (3%) | 0.017 | 0.6 |

| #17 | <0.001 | 0.3 (12%) | 0.003 | 0.3 | −0.8 (−20%) | <0.001 | 1.4 | −0.6 (−15%) | <0.001 | 1.1 |

| #18 | <0.001 | −0.3 (−12%) | <0.001 | 0.5 | 0.1 (5%) | 0.456 | - | −0.2 (−8%) | 0.036 | 0.4 |

| #20 | <0.001 | 0 (0%) | 0.975 | - | −0.8 (−18%) | <0.001 | 1.2 | −0.8 (−18%) | <0.001 | 1.1 |

| #21 | 0.004 | 0.2 (10%) | 0.170 | - | 0.1 (4%) | 0.301 | - | 0.3 (14%) | 0.003 | 0.4 |

| #23 | 0.500 | −0.1 (−3%) | - | - | 0 (0%) | - | - | 0 (0%) | - | - |

| Mean | <0.001 | 0 (0%) | 0.199 | - | −0.1 (−3%) | <0.001 | 0.2 | −0.1 (−3%) | 0.002 | 0.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pécresse, B.; Moiroud, C.; Hanne-Poujade, S.; Hatrisse, C.; De Azevedo, E.; Coudry, V.; Jacquet, S.; Audigié, F.; Chateau, H. Group and Individual Changes in Spinal Mobility During a 12-Week Rehabilitation Program Including Swimming in Horses with Axial Musculoskeletal Lesions. Animals 2026, 16, 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010103

Pécresse B, Moiroud C, Hanne-Poujade S, Hatrisse C, De Azevedo E, Coudry V, Jacquet S, Audigié F, Chateau H. Group and Individual Changes in Spinal Mobility During a 12-Week Rehabilitation Program Including Swimming in Horses with Axial Musculoskeletal Lesions. Animals. 2026; 16(1):103. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010103

Chicago/Turabian StylePécresse, Baptiste, Claire Moiroud, Sandrine Hanne-Poujade, Chloé Hatrisse, Emeline De Azevedo, Virginie Coudry, Sandrine Jacquet, Fabrice Audigié, and Henry Chateau. 2026. "Group and Individual Changes in Spinal Mobility During a 12-Week Rehabilitation Program Including Swimming in Horses with Axial Musculoskeletal Lesions" Animals 16, no. 1: 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010103

APA StylePécresse, B., Moiroud, C., Hanne-Poujade, S., Hatrisse, C., De Azevedo, E., Coudry, V., Jacquet, S., Audigié, F., & Chateau, H. (2026). Group and Individual Changes in Spinal Mobility During a 12-Week Rehabilitation Program Including Swimming in Horses with Axial Musculoskeletal Lesions. Animals, 16(1), 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010103