While post-mortem studies revealed infectious diseases as the leading cause of mortality [

1], particularly MD and

E. coli septicemia [

2,

6,

7,

8], studies focusing on emergency visits identified trauma cases [

15] and reproductive tract diseases as the most common issues [

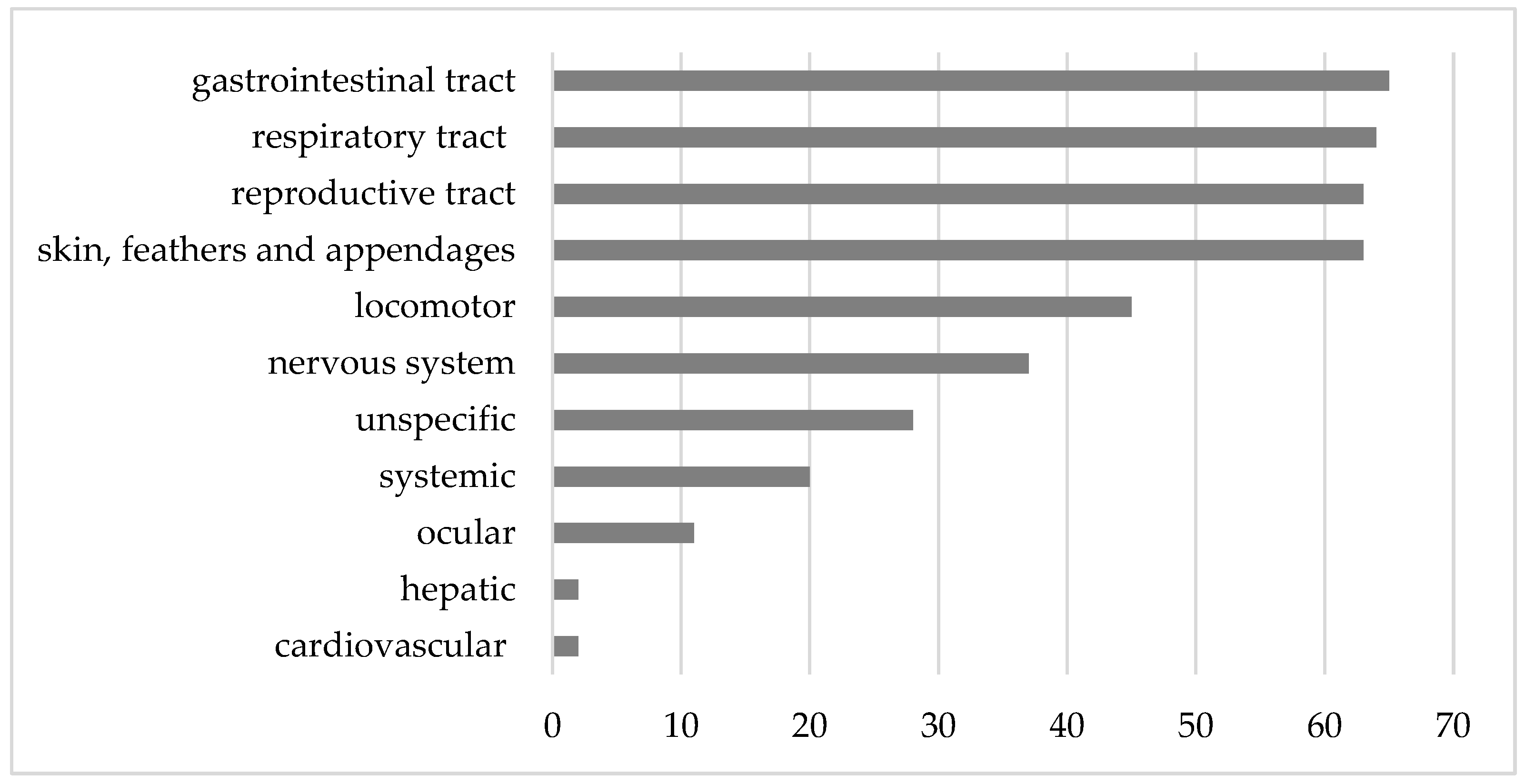

3]. The data from this survey indicated a diverse range of problems, with relatively even distributions among pathologies associated with the gastrointestinal tract (15.5%), respiratory tract (15.3%), reproductive tract (15.0%), and skin, feathers, and appendages (15.0%).

4.5.1. Gastrointestinal Tract

The incidence of diseases or clinical signs associated with the gastrointestinal tract was notably high (15.5%) in this study, with most cases linked to endoparasites. An extensive survey of non-commercial chicken owners in the United Kingdom identified diarrhea as the second most common health issue after red mite infestations [

4]. In contrast, only 31.2% of these owners reported always deworming their chickens or routinely sending fecal samples for testing. Alarmingly, 24.4% stated that they never perform these preventative measures [

4].

Within this survey, cases attributed to endoparasites were predominantly associated with roundworms, namely,

Capillaria and

Ascaridia. Followed by coccidia, particularly in chickens younger than 1 year. Findings from other studies identified coccidiosis as the most common endoparasitic infection in backyard chickens [

1,

2,

6]. However, the true prevalence of endoparasitic infections in backyard chickens could not be determined in this study, as not all chickens underwent fecal examination. There is likely a significant bias toward cases presenting with clinical signs attributed to gastrointestinal disease.

Interestingly, gastrointestinal parasites were mostly not associated with clinical signs. Notably, 58% of positive fecal samples had only one detected parasite, while 42% were positive for two or more parasites. The presence of multiple parasites in positive fecal samples was expected, given the typically extensive husbandry practices in backyard poultry. To mitigate the risks of endoparasitic infections, regular check-ups—ideally every six months—with fecal samples collected from the entire flock are recommended. This approach ensures accurate diagnosis and treatment, when necessary, while also facilitating environmental control measures. Such measures include rotating pens, maintaining low population densities, frequently removing droppings, ensuring runs are well-drained, allowing droppings and soil to dry, providing good ventilation, and ensuring access to ultraviolet light [

17].

The second most prevalent findings associated with the gastrointestinal tract were pathologies of the crop, primarily presenting as crop impactions with grass bezoars, all of which necessitated surgical intervention. Generally, crop abnormalities like delayed passage or complete stasis often signal underlying gastrointestinal or systemic diseases [

15]. Hence, such cases should always undergo comprehensive diagnostic workups.

The prevalence of cloacal prolapse was relatively low, accounting for 2.4% (10/419), with the majority presenting as emergencies (7/10). A slightly higher prevalence of 3.6% among emergency presentations only was documented in a previous study [

3], which exhibited a notably poor outcome for these cases, with a survival rate of only 25%. Conversely, in this current study, the observed cases generally had a favorable outcome, with 7 cases (70%) resulting in recovery, only one case leading to death, and two cases lost for follow-up. Overall, five cloacal prolapses were attributed to issues in the reproductive tract, four to gastrointestinal tract problems, and in one case the cause remained unidentified. Cloacal prolapse should always be considered as an emergency presentation [

3], necessitating immediate veterinary care and comprehensive examinations to identify the underlying causes of the condition. After emergency prolapse repositioning, diagnostic measures such as digital cloacal palpation, diagnostic imaging, and at least parasitological examination of feces are essential in these cases.

4.5.2. Respiratory Tract

In cases involving respiratory tract diseases, the highest proportion was attributed to upper respiratory tract infections. Further examinations of these cases unveiled the identification of various agents. Among these, E. coli and mycoplasmas stood out as the most associated bacterial agents, although various bacteria were isolated.

Mycoplasmosis denotes a contagious disease prevalent worldwide affecting the respiratory, musculoskeletal, and reproductive tracts of poultry [

18]. Control measures and serology-based surveillance programs in commercial poultry flocks across many countries have successfully eradicated pathogenic

Mycoplasma species from most chicken breeder flocks. However, this does not apply to backyard chicken breeders and flocks, where mycoplasmosis appears to be the most common respiratory condition [

7].

In this survey, a total of 35 chickens were tested for mycoplasmas, with 25 showing positive results. Among them, the majority were associated with upper respiratory tract infections. Notably, five of these chickens tested positive for M. gallisepticum, a pathogen known to cause chronic respiratory disease and significant economic losses in poultry production. This finding suggests that backyard flocks could serve as reservoirs for M. gallisepticum, posing a potential risk of spillover into commercial operations. Although most of these chickens were colonized by mycoplasmas with no or little evidence of pathogenicity (apathogenic/opportunistic Mycoplasma species), many presented concurrent bacterial infections, suggesting the potential involvement of these mycoplasmas in the ongoing infections. This underscores the significance, especially in cases suspicious of respiratory tract infections, not only of conducting regular microbiological cultures but also specifically testing for mycoplasmas.

Escherichia coli is widely recognized for its involvement in various infections and is considered a significant cause of mortality in backyard poultry [

2,

6,

7]. In this study,

E. coli was the most common cause of upper respiratory tract infection. The second most common isolate was

P. multocida, the causative agent of fowl cholera, a highly contagious disease responsible for significant mortality and economic losses in commercial poultry. Low detection rates of

P. multocida in backyard flocks have been previously described [

2,

6,

7]. This finding suggests that while

P. multocida remains a pathogen of concern, its prevalence in backyard chickens may be sporadic, warranting further investigation into the ecological and epidemiological factors influencing its occurrence. Importantly, outbreaks of fowl cholera are notifiable diseases in some countries.

A broad range of bacterial pathogens was detected, emphasizing the importance of conducting microbiological examinations and susceptibility testing to ensure appropriate antibiotic treatment.

Overall, a prevalence of 15.3% of diseases/clinical signs associated with the respiratory tract was observed during the study period. In contrast, previous studies focusing on emergency presentations noted lower occurrences of respiratory tract pathologies at 6.4% [

15] and 12.6% [

3] of the study population, respectively. High prevalences of mixed respiratory infections have also been identified as a common cause of mortality and illness in a prior study on mortality and morbidity of small poultry flocks, accounting for 21% of primary diagnoses [

1]. This aligns with the understanding that multiple respiratory pathogens can concurrently affect the flock, contributing to multifactorial respiratory infections. The observation that mixed respiratory infections were a primary cause of clinical signs or death among small flocks, while unusual, is consistent with our findings.

In addition, various viral agents can affect the respiratory tract of chickens, while they are generally considered uncommon in backyard poultry [

7,

19]. In this survey, three chickens with lower respiratory tract diseases where diagnosed with IB (1.9%), and one with ILT (0.64%). The rarity of positive cases among suspicious instances aligns with findings from previous studies. It is important to note that in areas with endemic diseases, such as ILT in the United States, high prevalences could also exist in backyard poultry flocks [

20]. Furthermore, veterinarians treating pet chickens should be aware that birds infected with mycoplasma, ILT, or IBV often encounter secondary gram-negative bacterial infections [

1].

4.5.3. Reproductive Tract

The second most prevalent set of diseases observed were reproductive tract pathologies in hens, also commonly seen in commercial layer flocks [

21,

22]. These pathologies are often multifactorial in origin [

17]. While the ancestors of hens laid 1–2 clutches annually, commercial egg-layer breeds, producing approximately 301 eggs yearly, display non-seasonal laying behavior. This intense production predisposes them to reproductive issues. Additionally, infectious diseases, including IBV, MD, chronic stress-induced immunosuppression, and concurrent illnesses leading to secondary bacterial infections, notably

E. coli ascending from the cloaca [

23], contribute to infections of the reproductive tract. These infections commonly result in pathologies such as salpingitis, salpinx impaction, and egg yolk peritonitis. Testing affected chickens for underlying agents, such as IBV, could provide valuable insights into flock health, though it may not significantly influence treatment decisions for individual hens.

Reproductive tract diseases are frequently reported in backyard chickens, often presenting in older birds at the end of their peak laying performance. For example, a US survey reported a median age of 1.75 years for affected chickens [

15], whereas in this study, the median age was 2.5 years (range: 0.4–6.4 years).

Treatment for reproductive tract diseases often requires surgery [

24], successful procedures ensuring a good quality of life for the chickens [

25]. Salpingohysterectomy is the most commonly reported surgical intervention, reflecting the commitment of backyard chicken owners to treat their chickens as pets rather than food sources. This trend is particularly notable in “rescued” hens from commercial flocks nearing the end of their productive lifespan [

24]. However, salpingohysterectomy is a complex and costly procedure requiring detailed anatomical knowledge and surgical expertise [

26]. Consequently, it is not routinely performed in general veterinary practices [

15]. Referral to specialized clinics should be discussed with owners in such cases. For owners unable to afford surgery or when conservative management fails to resolve severe issues, such as oviduct impaction or egg-bound conditions, humane euthanasia must be considered as an ethical option.

4.5.4. Skin, Feathers, and Appendages

Among the integument-related conditions observed, traumatic skin wounds accounted for nearly half of the cases. During the study period, a total prevalence of 10.3% was noted for trauma cases. Previous studies examining emergency presentations of backyard chickens highlighted an even higher prevalence of trauma cases [

3,

15]. Predation emerged as the leading cause of these injuries [

5], a finding supported by our data. This highlights the importance of emergency veterinary services for pet chickens and underscores the need to advise owners to house their chickens in predator-proof enclosures.

In terms of outcomes, the overall prognosis for traumatic skin wounds was largely positive, with 16 out of 24 wounds healing without complications. However, many cases (15) required surgical intervention. Managing traumatic wounds in chickens follows similar principles to those used for dogs and cats, with adjustments made for the unique anatomical and physiological characteristics of poultry [

15]. Despite this, some cases resulted in mortality: four chickens died, and four were euthanized. Notably, myiasis was associated with poor outcomes, contributing to four unfavorable prognoses.

Ectoparasites and pododermatitis constituted the second most common integument-related diseases observed. The overall prevalence of ectoparasites (3.6%) and pododermatitis (3.1%) was relatively low. Interestingly, surveys of backyard chicken owners frequently identify external parasites as the most common health issue affecting their flocks [

4,

5]. This discrepancy may arise because disease recognition can sometimes be challenging for owners. Ectoparasites are easily noticeable, and owners are generally more familiar with parasitic diseases compared to other infectious diseases [

5].

Pododermatitis often results from husbandry deficiencies such as inadequate substrates, poor perches, underlying wounds, and obesity [

17,

27]. Addressing these cases requires implementing corrective measures focused on improving husbandry practices and environmental conditions. Recently, a novel approach using 3D-printed silicone shoes for treating pododermatitis in chickens has been described and has shown promising success [

28].

4.5.6. Infectious and Neoplastic Diseases

Marek’s disease is considered endemic in poultry populations [

7]. While commercial poultry management has effectively controlled MD outbreaks through selective breeding and vaccination (administered in ovo or at day of hatch) [

30], backyard poultry remain vulnerable. Vaccination in backyard flocks is less common, making MD a frequent cause of mortality [

1,

2,

6]. Reported prevalences range from 11% to 27% in post-mortem studies [

1,

2,

6,

7,

8].

In this study, MD was suspected in 33 cases (7.9%) among the 419 chickens presented at our clinic. Necropsy and histopathology were performed in 10 of these cases, all of which confirmed MD. Studies of emergency presentations report varying prevalences, including 7.7% [

15] and 0.6% [

3], respectively. MD manifests in various forms [

31], typically affecting chickens between 10 and 20 weeks of age, though cases can occur outside this range. Of the confirmed cases in this study, eight chickens had known ages: four were younger than one year (2, 5, 7, and 9 months), and four were older than one year.

Veterinarians managing backyard chickens should maintain a high index of suspicion for MD. Once present in a flock, eradication is nearly impossible. The prognosis for individual chickens showing clinical signs is poor, though some may experience temporary improvement. Despite MD being confirmable only through post-mortem diagnostics, many owners choose to pursue treatment. Unfortunately, no specific treatment is available. Care typically involves anti-inflammatory medications along with supportive measures, such as fluid therapy, vitamin supplementation, force-feeding when necessary, and time.

Among the suspected MD cases in this study, eight chickens were lost to follow-up, nine were euthanized, two died, and four showed clinical improvement. Educating owners about MD is essential, particularly emphasizing the importance of acquiring vaccinated chickens to prevent outbreaks in new flocks. Such discussions are critical when MD is present in a flock, as many owners are unaware of the disease [

5].

A comprehensive survey evaluating causes of mortality in backyard chickens in the United States [

2] identified neoplasia or lymphoproliferative diseases as the most common primary diagnoses (42%) among deceased chickens. Diseases caused by avian leukosis virus (ALV) exhibit similar pathomorphological changes to MD, making differentiation challenging. In our study, only two chickens were confirmed to have ALV. However, this number may be underestimated, as not all euthanized or deceased chickens underwent necropsy. Additionally, some systemic neoplastic cases, such as carcinomatosis, may have involved underlying viral infections that went undetected.

While several zoonotic pathogens theoretically can be present in backyard chickens, none of the chickens in this survey showed suspicion or tested positive for avian influenza virus or Newcastle disease virus. Beyond these well-known viral zoonoses, various enteric bacteria have zoonotic potential, including Salmonella enterica and Campylobacter spp. Detection of these pathogens requires specific cultural procedures, which were performed on samples from the intestinal tract in this study. Indeed, Campylobacter spp. were detected in two chickens, though further species identification was not conducted.

Previous studies [

1,

16] have not strongly indicated that backyard poultry flocks act as significant reservoirs for these zoonotic diseases or pose substantial risks to public health [

6]. However, it is worth noting that while rare,

Salmonella spp. is supposed to be more common in small backyard flocks compared to the well-controlled commercial enterprises [

17]. This may be attributed to the fact that backyard chickens often have outdoor access and free-range opportunities, increasing their contact with ubiquitous environmental bacteria. Conversely, a 2018 study found that

Salmonella prevalence at the bird level in smallholder flocks was significantly lower than in federally inspected commercial flocks [

32]. However,

Campylobacter spp. showed higher prevalences in small poultry flocks compared to those reported for commercial broiler chickens from federal inspections [

1]. There is no legal mandate to test smaller flocks for

Salmonella or

Campylobacter spp. Nevertheless, flock owners should be encouraged to assess the status of their chickens, especially if the eggs are intended for human consumption, to mitigate any potential zoonotic risks.

A common neoplastic condition observed in chickens is known as carcinomatosis, characterized by adenocarcinoma, primarily originating from the reproductive system. This condition typically presents as multifocal metastatic masses spread throughout the abdominal organs, often involving the gastrointestinal tract and sometimes accompanied by ascites [

7,

25,

33]. In this study, carcinomatosis was the most prevalent neoplastic condition identified.

Spontaneous adenocarcinomas in the reproductive tract of laying hens are well-documented and represent a significant area of research, particularly because chickens serve as models for studying human ovarian adenocarcinomas [

34,

35]. This type of neoplasia becomes increasingly common as hens age [

36], a trend reflected in our data. The high incidence of reproductive tract neoplasia, particularly in chickens older than two years, aligns with findings from previous studies [

1,

6].

Apart from reproductive tract neoplasia, a few other tumor types were identified, contributing to an overall neoplastic case incidence of 6.2%.