From Mutation to Manifestation: Evaluation of a PKLR Gene Truncation Caused by Exon Skipping in a Schnauzer Terrier

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and Clinical Evaluation

2.2. RNA and Genomic DNA Extraction and cDNA Synthesis

2.3. Gene Cloning and Recombinant Protein Expression

2.4. Enzyme Activity Assay

3. Results

3.1. Histopathological Analysis

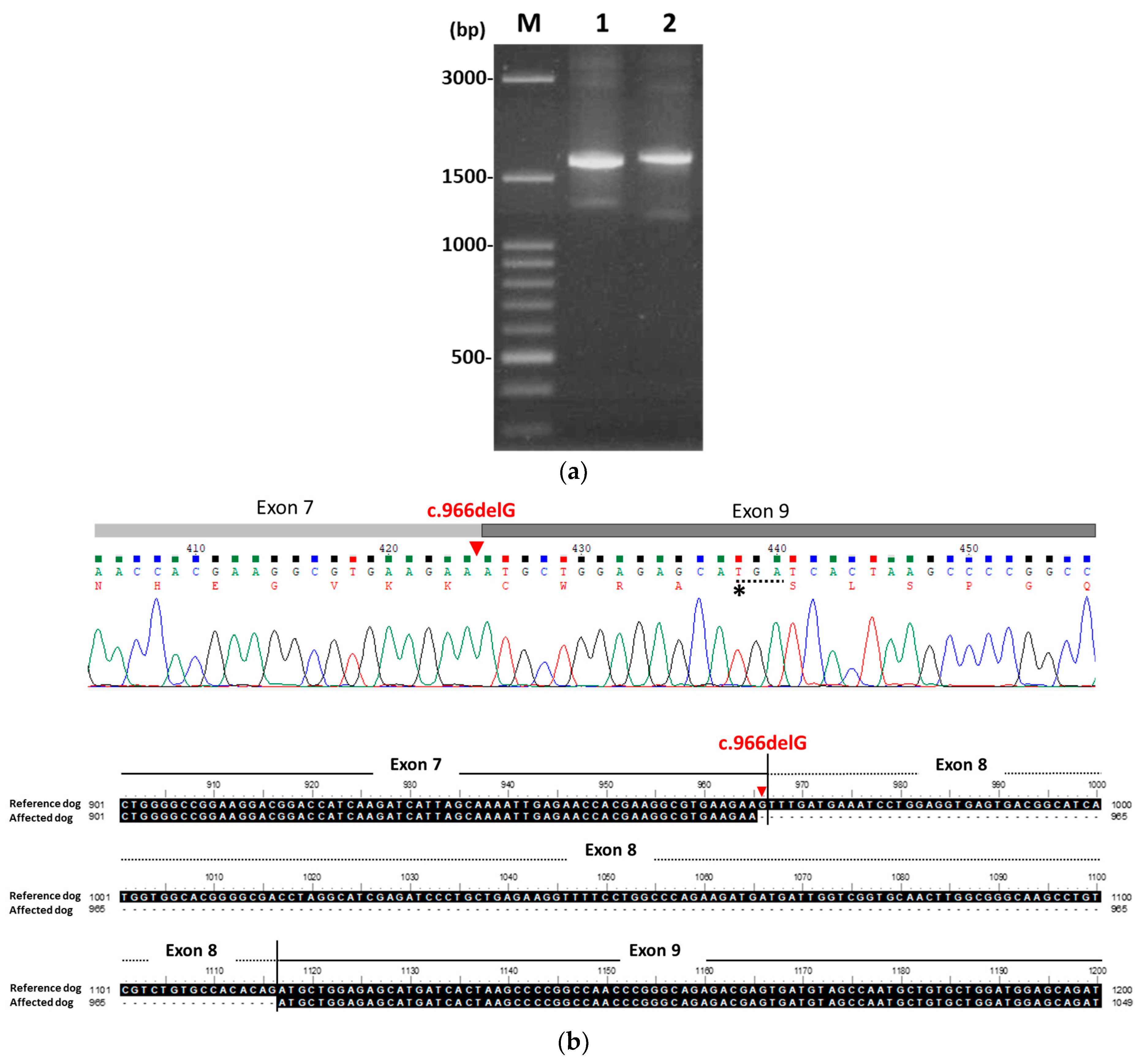

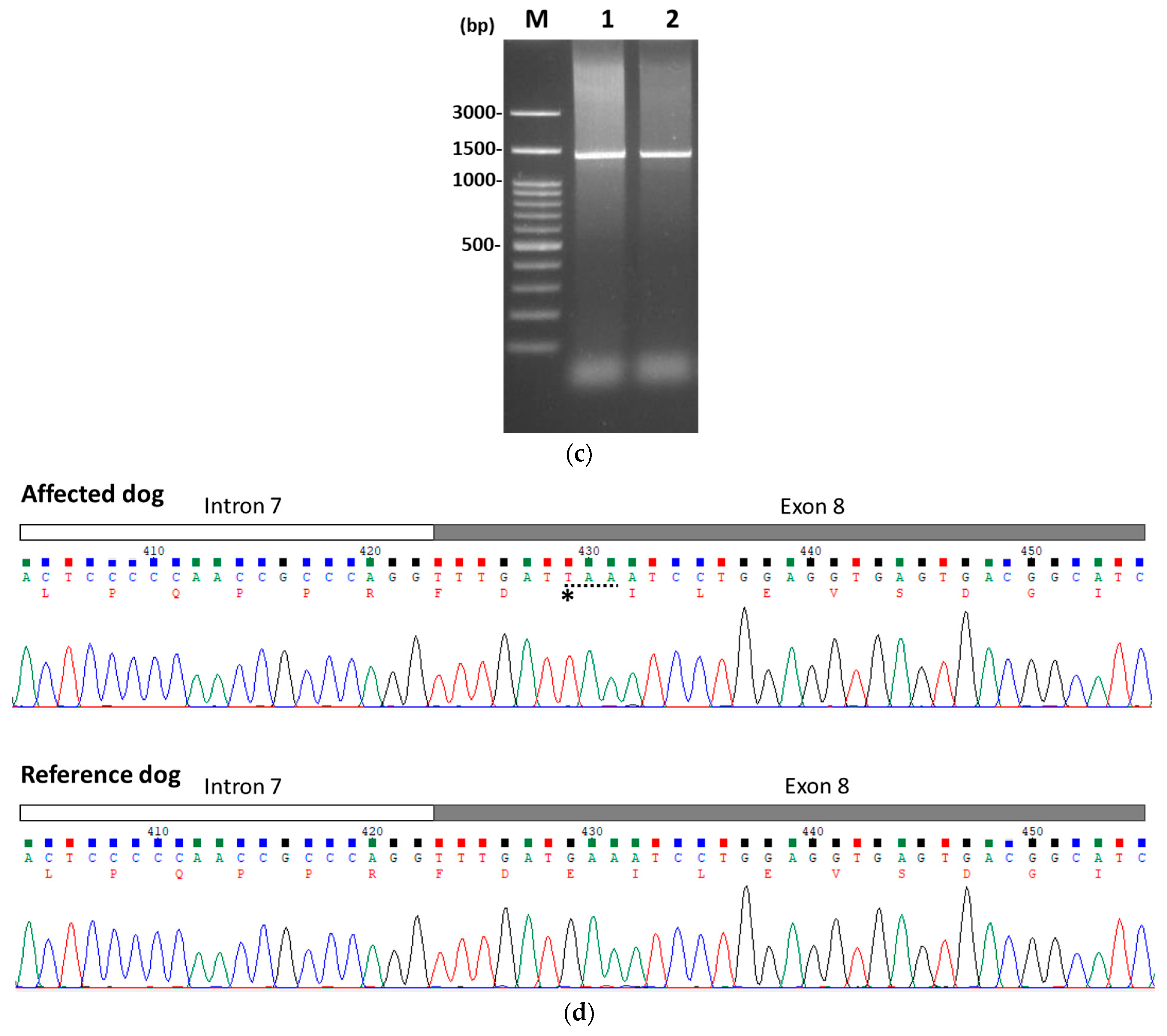

3.2. Identification of PKLR Mutation

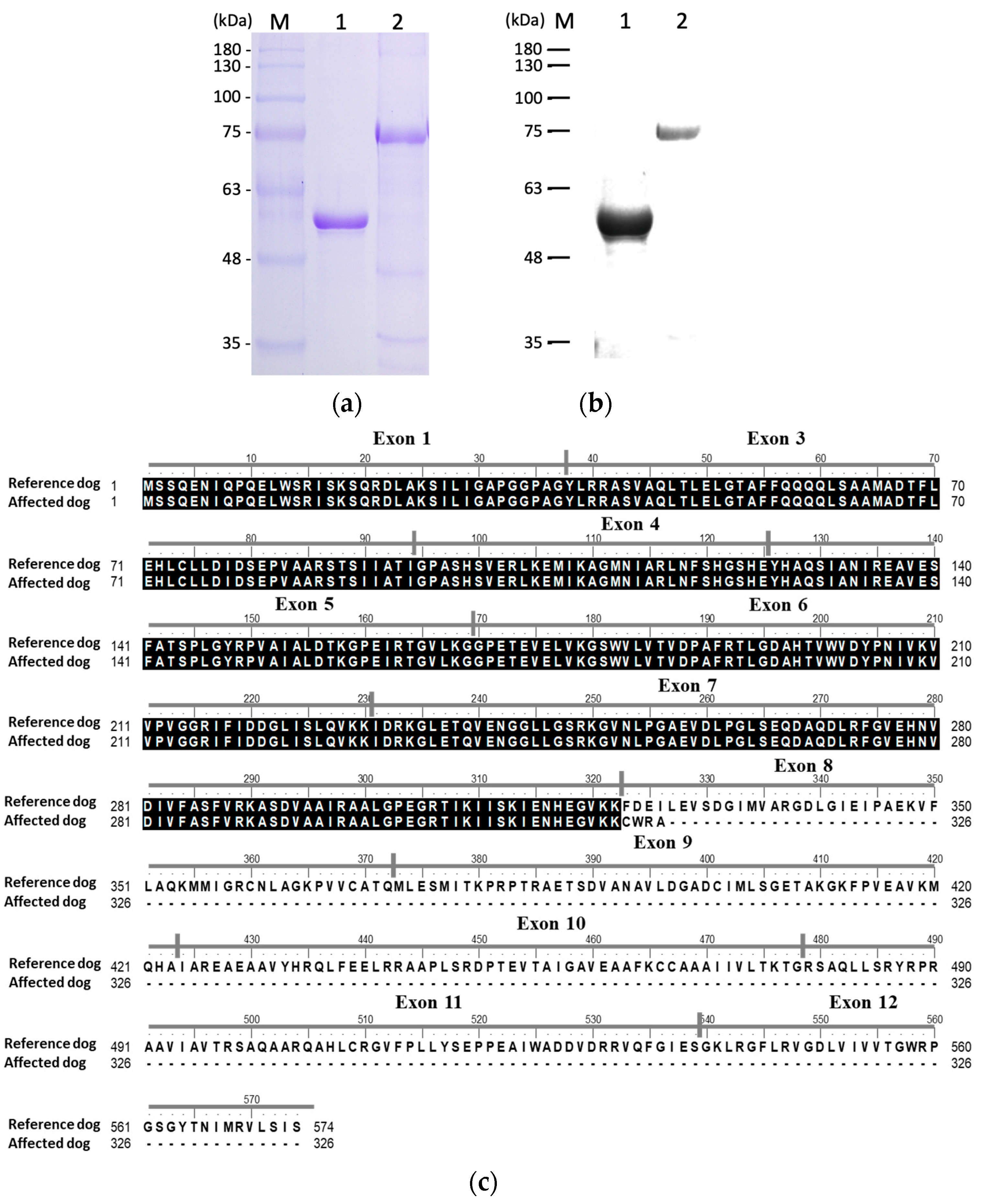

3.3. Recombinant Protein Expression and Confirmation

3.4. Functional Characterization of Recombinant PK

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADP | Adenosine diphosphate |

| ATP | Adenosine triphosphate |

| ESEs | Exon-splicing enhancers |

| Hct | Hematocrit |

| LDH | Lactate dehydrogenase |

| NADH | Reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide |

| NM | Non-missense |

| PBST | PBS containing 0.1% v/v Tween 20 |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| PEP | Phosphoenolpyruvate |

| PK | Pyruvate kinase |

| PKD | Pyruvate kinase deficiency |

| PTCs | Premature stop codons |

| rPK | Recombinant pyruvate kinase |

| SDS-PAGE | Sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis |

| TBIL | Total bilirubin |

Appendix A

| Dyas | AST (U/L) | ALT (U/L) | ALP (U/L) | TBIL (mg/dL) | GLU (mg/dL) | BUN (mg/dL) | CREA (mg/dL) | TP (g/dL) | ALB (g/dL) | Na (mEq/L) | K (mEq/L) | Cl (mEq/L) | Ca (mEq/L) | Phos (mEq/L) | Mg (mEq/L) | CO2 (mmol/L) | OSMA | GLO (g/dL) | A/G | Chol (mEq/L) | GAP | TRIG (mg/dL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 1 | 111 | 108 | 150 | 0.55 | 103 | 28 | 0.9 | 7.1 | 3.2 | 142 | 4.1 | 110 | - | - | - | - | 308 | 3.9 | 0.8 | - | - | - |

| 2 | - | - | - | 0.42 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 10 | - | - | - | 0.22 | 122.0 | - | - | 5.9 | 3.1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2.8 | 1.1 | - | - | - |

| 30 | - | - | - | 0.37 | 136.0 | - | - | 6.2 | 3.5 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2.7 | 1.3 | - | - | - |

| 38 | - | - | - | 0.28 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 82 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 84 | - | 103.0 | 125.0 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 118 | - | - | - | 0.7 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 233 | 30.0 | 21.0 | 68.0 | 0.74 | 133.0 | 10.0 | 0.7 | 6.6 | 2.9 | 144.0 | 4.6 | 111.0 | 10.3 | 4.5 | 2.3 | 25.7 | 308.0 | - | - | 177.0 | 11.9 | - |

| 360 | 35.0 | 27.0 | 47.0 | 0.56 | 118.0 | 19.0 | 0.6 | 7.1 | 3.3 | 145.0 | 4.2 | 113.0 | 10.3 | 4.9 | 1.9 | 19.2 | 312.0 | 3.8 | 0.9 | 161.0 | 17.0 | - |

| 473 | 30.0 | 20.0 | 52.0 | 0.6 | 120.0 | 18.0 | 0.5 | 7.1 | 3.1 | 146.0 | 4.7 | 113.0 | 9.9 | 3.8 | 1.9 | 23.7 | 314.0 | 4.0 | 0.8 | 199.0 | 14.0 | 52.0 |

| 609 | 30.0 | 20.0 | 58.0 | 0.54 | 117.0 | 19.0 | 0.5 | 7.1 | 3.1 | 145.0 | 4.5 | 110.0 | 10.5 | 3.2 | 2.0 | 26.1 | 312.0 | 4.0 | 0.8 | 181.0 | 13.4 | 152.0 |

| Days | RBC (M/μL) | HCT (%) | HGB (g/dL) | MCV (fL) | MCH (pg) | MCHC (g/dL) | RDW (%) | %Retic | Retic (K/μL) | Retic-HGB (pg) | WBC (K/μL) | %Neu | %Lym | %Mono | %Eos | %Baso | PLT (K/μL) | MPV (fL) | PDW (fL) | PCT (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1.3 | 10.6 | 2.0 | 79.7 | 21.1 | 26.4 | 21.3 | - | - | - | 26.7 | - | - | - | - | - | 160.0 | 10.5 | 18.2 | 0.168 |

| 1 | 1.7 | 9.1 | 3.4 | 71.7 | 26.8 | 37.4 | - | 40.6 | 516.1 | 21.7 | 26.09 | 53.5 | 32.5 | 13.4 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 291.0 | 17.5 | - | 0.51 |

| 2 | 4.5 | 32.3 | 10.5 | 71.6 | 23.3 | 32.5 | 25 | 14.2 | 639.5 | 20.2 | 19.81 | 54.6 | 29.8 | 15.3 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 323.0 | 16.7 | - | 0.54 |

| 10 | 4.29 | 26.8 | 10.2 | 62.5 | 23.8 | 38.1 | 18.5 | 4.1 | 177.2 | 22.8 | 10.17 | 49.0 | 39.1 | 7.9 | 2.5 | 1.5 | 602.0 | 11.3 | 11.4 | 0.68 |

| 30 | 3.71 | 24.9 | 8.4 | 67.1 | 22.6 | 33.7 | 24.8 | 20.2 | 747.9 | 20.3 | 13.83 | 56.0 | 35.0 | 6.4 | 1.9 | 0.2 | 410.0 | 15.5 | - | 0.64 |

| 38 | 3.28 | 22.5 | 7.5 | 68.9 | 22.9 | 33.3 | 26.2 | 21.9 | 717.0 | 20.4 | 14.48 | 55.6 | 36.5 | 5.9 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 388.0 | 14.9 | - | 0.58 |

| 84 | 2.49 | 17.6 | 5.9 | 70.7 | 23.7 | 33.5 | - | 27.3 | 679.8 | 20.0 | 17.7 | 68.4 | 22.9 | 7.1 | 1.5 | 0.1 | 373.0 | 15.2 | 21.8 | 0.57 |

| 86 | 4.7 | 32.3 | 10.2 | 68.7 | 21.7 | 31.6 | 22.4 | 11.8 | 554.6 | 23.0 | 13.81 | 76.9 | 17.5 | 4.7 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 426.0 | 15.8 | - | 0.67 |

| 88 | 4.82 | 30.5 | 9.8 | 63.3 | 20.3 | 32.1 | 16.3 | 5.1 | 245.8 | 15.8 | 8.97 | 58.1 | 26.5 | 13.2 | 1.8 | 0.4 | 587.0 | 15.2 | 13.6 | 0.8 |

| 103 | 4.05 | 26.9 | 8.5 | 66.4 | 21.0 | 31.6 | 23 | 13.9 | 560.9 | 20.7 | 16.4 | 66.0 | 26.8 | 4.4 | 2.6 | 0.2 | 463.0 | 14.9 | 19.6 | 0.69 |

| 118 | 3.69 | 24.4 | 8.3 | 66.1 | 22.5 | 34.0 | 26.7 | 17.8 | 656.5 | 21.9 | 16.07 | 63.7 | 28.6 | 4.7 | 2.9 | 0.1 | 454.0 | 14.9 | 19.1 | 0.68 |

| 233 | 2.3 | 16.0 | 5.4 | 69.6 | 23.5 | 33.8 | - | 38.2 | 877.9 | 19.7 | 17.21 | 65.0 | 28.7 | 5.0 | 1.1 | 0.2 | 635.0 | 14.1 | 19 | 0.9 |

| 360 | 2.3 | 15.8 | 5.5 | 68.4 | 23.8 | 34.8 | - | 43.5 | 1005.8 | 20.2 | 16.99 | 56.5 | 36.6 | 5.2 | 1.6 | 0.1 | 647.0 | 13.7 | 17.3 | 0.89 |

| 473 | 2.43 | 18.9 | 5.7 | 77.8 | 23.5 | 30.2 | - | 47.1 | 1144.8 | 21.5 | 14.95 | 47.8 | 44.7 | 5.8 | 1.6 | 0.1 | 459.0 | 15.0 | 18.7 | 0.69 |

| 609 | 2.58 | 21.7 | 6.4 | 84.1 | 24.8 | 29.5 | - | 46.7 | 1204.9 | 25.4 | 16.63 | 47.5 | 45.7 | 5.7 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 537.0 | 15.2 | 20.9 | 0.82 |

| Days | Collection | Color | Clarity | Sp.Gr. | pH | Leu | Pro | Glu | Ket | Ubg (EU/dL) | Bil | BLD (Ery/μL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 118 | Void | Amber | Slightly cloudy | - | 7.0 | 25 | Trace | - | - | 1 | 1 | - |

| 360 | Void | Amber | Cloudy | 1.035 | 8.0 | - | - | - | - | 4 | 3 | - |

| 473 | Void | Dark yellow | Slightly cloudy | 1.042 | 6.5 | - | - | - | - | 1 | 3 | - |

| 609 | Void | Orange-yellow | Cloudy | 1.035 | 7.0 | - | Trace | - | - | 1 | 3 | 25 |

References

- Bianchi, P.; Fermo, E.; Lezon-Geyda, K.; van Beers, E.J.; Morton, H.D.; Barcellini, W.; Glader, B.; Chonat, S.; Ravindranath, Y.; Newburger, P.E.; et al. Genotype-phenotype correlation and molecular heterogeneity in pyruvate kinase deficiency. Am. J. Hematol. 2020, 95, 472–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, P.; Fermo, E. Molecular heterogeneity of pyruvate kinase deficiency. Haematologica 2020, 105, 2218–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciak, K.; Jurkiewicz, A.; Strojny, W.; Adamowicz-Salach, A.; Romiszewska, M.; Jackowska, T.; Kwiecinska, K.; Poznanski, J.; Gora, M.; Burzynska, B. PKLR mutations in pyruvate kinase deficient Polish patients: Functional characteristics of c.101-1G>A and c.1058delAAG variants. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 2024, 107, 102841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitney, K.M.; Lothrop, C.D. Genetic test for pyruvate kinase deficiency of Basenjis. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 1995, 207, 918–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gultekin, G.I.; Raj, K.; Foureman, P.; Lehman, S.; Manhart, K.; Abdulmalik, O.; Giger, U. Erythrocytic pyruvate kinase mutations causing hemolytic anemia, osteosclerosis, and secondary hemochromatosis in dogs. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2012, 26, 935–944. [Google Scholar]

- Barrs, V.R.; Giger, U.; Wilson, B.; Chan, C.T.; Lingard, A.E.; Tran, L.; Seng, A.; Canfield, P.J.; Beatty, J.A. Erythrocytic pyruvate kinase deficiency and AB blood types in Australian Abyssinian and Somali cats. Aust. Vet. J. 2009, 87, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueno, H.; Itoh, T.; Nasuno, T.; Konno, W.; Kondo, A.; Konishi, I.; Inukai, H.; Kokubo, D.; Isaka, M.; Islam, M.S.; et al. Pyruvate kinase deficiency mutant gene carriage in stray cats and rescued cats from animal hoarding in Hokkaido, Japan. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2023, 85, 972–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianchi, P.; Fermo, E.; Glader, B.; Kanno, H.; Agarwal, A.; Barcellini, W.; Eber, S.; Hoyer, J.D.; Kuter, D.J.; Magalhães Maia, T.; et al. Addressing the diagnostic gaps in pyruvate kinase deficiency: Consensus recommendations on the diagnosis of pyruvate kinase deficiency. Am. J. Hematol. 2019, 94, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- van Beers, E.J.; Al-Samkari, H.; Grace, R.F.; Barcellini, W.; Glenthøj, A.; DiBacco, M.; Wind-Rotolo, M.; Xu, R.; Beynon, V.; Patel, P.; et al. Mitapivat improves ineffective erythropoiesis and iron overload in adult patients with pyruvate kinase deficiency. Blood Adv. 2024, 8, 2433–2441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaninoni, A.; Marra, R.; Fermo, E.; Consonni, D.; Andolfo, I.; Marcello, A.P.; Rosato, B.E.; Vercellati, C.; Barcellini, W.; Iolascon, A.; et al. Evaluation of the main regulators of systemic iron homeostasis in pyruvate kinase deficiency. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 4395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaucha, J.A.; Yu, C.; Lothrop, C.D.; Nash, R.A.; Sale, G.; Georges, G.; Kiem, H.P.; Niemeyer, G.P.; Dufresne, M.; Cao, Q.; et al. Severe canine hereditary hemolytic anemia treated by nonmyeloablative marrow transplantation. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2001, 7, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giger, U.; Noble, N.A. Inherited erythrocyte pyruvate kinase deficiency in Basenjis with chronic hemolytic anemia. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 1991, 198, 1755–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schormann, N.; Hayden, K.L.; Lee, P.; Banerjee, S.; Chattopadhyay, D. An overview of structure, function, and regulation of pyruvate kinases. Protein Sci. 2019, 28, 1771–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentini, G.; Chiarelli, L.R.; Fortin, R.; Dolzan, M.; Galizzi, A.; Abraham, D.J.; Wang, C.; Bianchi, P.; Zanella, A.; Mattevi, A. Structure and function of human erythrocyte pyruvate kinase: Molecular basis of nonspherocytic hemolytic anemia. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 23807–23814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz, M.E.; Ponce, E. Pyruvate kinase: Current status of regulatory and functional properties. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2003, 135, 197–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurica, M.S.; Mesecar, A.; Heath, P.J.; Shi, W.; Nowak, T.; Stoddard, B.L. The allosteric regulation of pyruvate kinase by fructose-1,6-bisphosphate. Structure 1998, 6, 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Chiarelli, L.R.; Bianchi, P.; Abraham, D.J.; Galizzi, A.; Mattevi, A.; Zanella, A.; Valentini, G. Human erythrocyte pyruvate kinase: Characterization of the recombinant enzyme and a mutant form (R510Q) causing nonspherocytic hemolytic anemia. Blood 2001, 98, 3113–3120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentine, C.R. The association of nonsense codons with exon skipping. Mutation Res. 1998, 411, 87–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grace, R.F.; Barcellini, W. Management of pyruvate kinase deficiency in children and adults. Blood 2020, 136, 1241–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanella, A.; Fermo, E.; Bianchi, P.; Chiarelli, L.R.; Valentini, G. Pyruvate kinase deficiency: The genotype-phenotype association. Blood 2007, 21, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.X.; Cartegni, L.; Zhang, M.Q.; Krainer, A.R. A mechanism for exon skipping caused by nonsense or missense mutations in BRCA1 and other genes. Nat. Genet. 2001, 27, 55–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ars, E.; Serra, E.; García, J.; Kruyer, H.; Gaona, A.; Lázaro, C.; Estivill, X. Mutations affecting mRNA splicing are the most common molecular defects in patients with neurofibromatosis type 1. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2000, 22, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, T.; Song, Y.; Liu, Z.; Chen, M.; Deng, J.; Xu, Y.; Lai, L.; Li, Z. CRISPR-induced exon skipping is dependent on premature termination codon mutations. Genome Biol. 2018, 17, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasiou, D.; Yu, Y.; Israelsen, W.J.; Jiang, J.-K.; Boxer, M.B.; Hong, B.S.; Tempel, W.; Dimov, S.; Shen, M.; Jha, A.; et al. Pyruvate kinase M2 activators promote tetramer formation and suppress tumorigenesis. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2012, 8, 839–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beutler, E.; Gelbart, T.; Kuhl, W.; Forman, L. DNA sequence abnormalities of human glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase variants. J. Biol. Chem. 1991, 266, 4145–4150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grahn, R.A.; Grahn, J.C.; Penedo, M.C.; Helps, C.R.; Lyons, L.A. Erythrocyte pyruvate kinase deficiency mutation identified in multiple breeds of domestic cats. BMC Vet. Res. 2012, 8, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Lee, S.Y.; Kim, N.; Lee, J.; Kim, D.S.; Park, J.; Cho, Y.G. Case report: Compound heterozygosity in PKLR gene with a large exon deletion and a novel rare p.Gly536Asp variant as a cause of severe pyruvate kinase deficiency. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 10, 1022980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanella, A.; Bianchi, P.; Baronciani, L.; Zappa, M.; Bredi, E.; Vercellati, C.; Alfinito, F.; Pelissero, G.; Sirchia, G. Molecular characterization of PKLR gene in Pyruvate Kinase–Deficient Italian Patients. Blood 1997, 89, 3847–3852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giger, U.; Mason, G.D.; Wang, P. Inherited erythrocyte pyruvate kinase deficiency in a Beagle dog. Vet. Clin. Pathol. 1991, 20, 83–86. [Google Scholar]

- Grace, R.F. Pyruvate kinase activators for treatment of pyruvate kinase deficiency. Hematology Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Program 2023, 1, 97–106. [Google Scholar]

- Meza, N.W.; Alonso-Ferrero, M.E.; Navarro, S.; Quintana-Bustamante, O.; Valeri, A.; Garcia-Gomez, M.; Bueren, J.A.; Bautista, J.M.; Segovia, J.C. Rescue of pyruvate kinase deficiency in mice by gene therapy using the human isoenzyme. Mol. Ther. 2009, 17, 2000–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagai, H.; Takazakura, E.; Oda, H.; Tsuji, H.; Terada, Y.; Makino, H.; Yamauchi, H.; Saitoh, K. An autopsy case of pyruvate kinase deficiency anemia associated with severe hemochromatosis. Intern. Med. 1994, 33, 56–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rab, M.A.E.; van Oirschot, B.A.; Kosinski, P.A.; Hixon, J.; Johnson, K.; Chubukov, V.; Dang, L.; Pasterkamp, G.; van Straaten, S.; van Solinge, W.W.; et al. AG-348 (mitapivat), an allosteric activator of red blood cell pyruvate kinase, increases enzymatic activity, protein stability, and adenosine triphosphate levels over a broad range of PKLR genotypes. Haematologica 2021, 106, 238–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Days | Hct (%) (37.3–61.7%) | Reticulocytes (×103/μL) (10–110) | TBIL (mg/dL) (0.09–0.25 mg/dL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 10.6 | – | – |

| 1 | 9.1 | 516.1 | 0.55 |

| 2 * | 32.3 | 639.5 | 0.42 |

| 10 | 26.8 | 177.2 | 0.22 |

| 30 | 24.9 | 747.9 | 0.37 |

| 38 | 22.5 | 717.0 | 0.28 |

| 84 | 17.6 | 679.8 | – |

| 86 * | 32.3 | 554.6 | – |

| 88 | 30.5 | 245.8 | – |

| 103 | 26.9 | 560.9 | – |

| 118 | 24.4 | 656.5 | 0.70 |

| 233 | 16.0 | 877.9 | 0.74 |

| 360 | 15.8 | 1005.8 | 0.56 |

| 473 | 18.9 | 1144.8 | 0.60 |

| 609 | 21.7 | 1204.9 | 0.54 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ma, T.Y.; Kuo, C.J.; Liu, P.C. From Mutation to Manifestation: Evaluation of a PKLR Gene Truncation Caused by Exon Skipping in a Schnauzer Terrier. Animals 2025, 15, 3634. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243634

Ma TY, Kuo CJ, Liu PC. From Mutation to Manifestation: Evaluation of a PKLR Gene Truncation Caused by Exon Skipping in a Schnauzer Terrier. Animals. 2025; 15(24):3634. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243634

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Tzu Yi, Chih Jung Kuo, and Pin Chen Liu. 2025. "From Mutation to Manifestation: Evaluation of a PKLR Gene Truncation Caused by Exon Skipping in a Schnauzer Terrier" Animals 15, no. 24: 3634. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243634

APA StyleMa, T. Y., Kuo, C. J., & Liu, P. C. (2025). From Mutation to Manifestation: Evaluation of a PKLR Gene Truncation Caused by Exon Skipping in a Schnauzer Terrier. Animals, 15(24), 3634. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243634