Diet Acceptance and Utilization Responses to Increasing Doses of Thymol in Beef Steers Consuming Forage

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experiment 1

2.2. Experiment 2

2.3. Laboratory Analysis

2.4. Calculations and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Experiment 1: Acceptance of Thymol

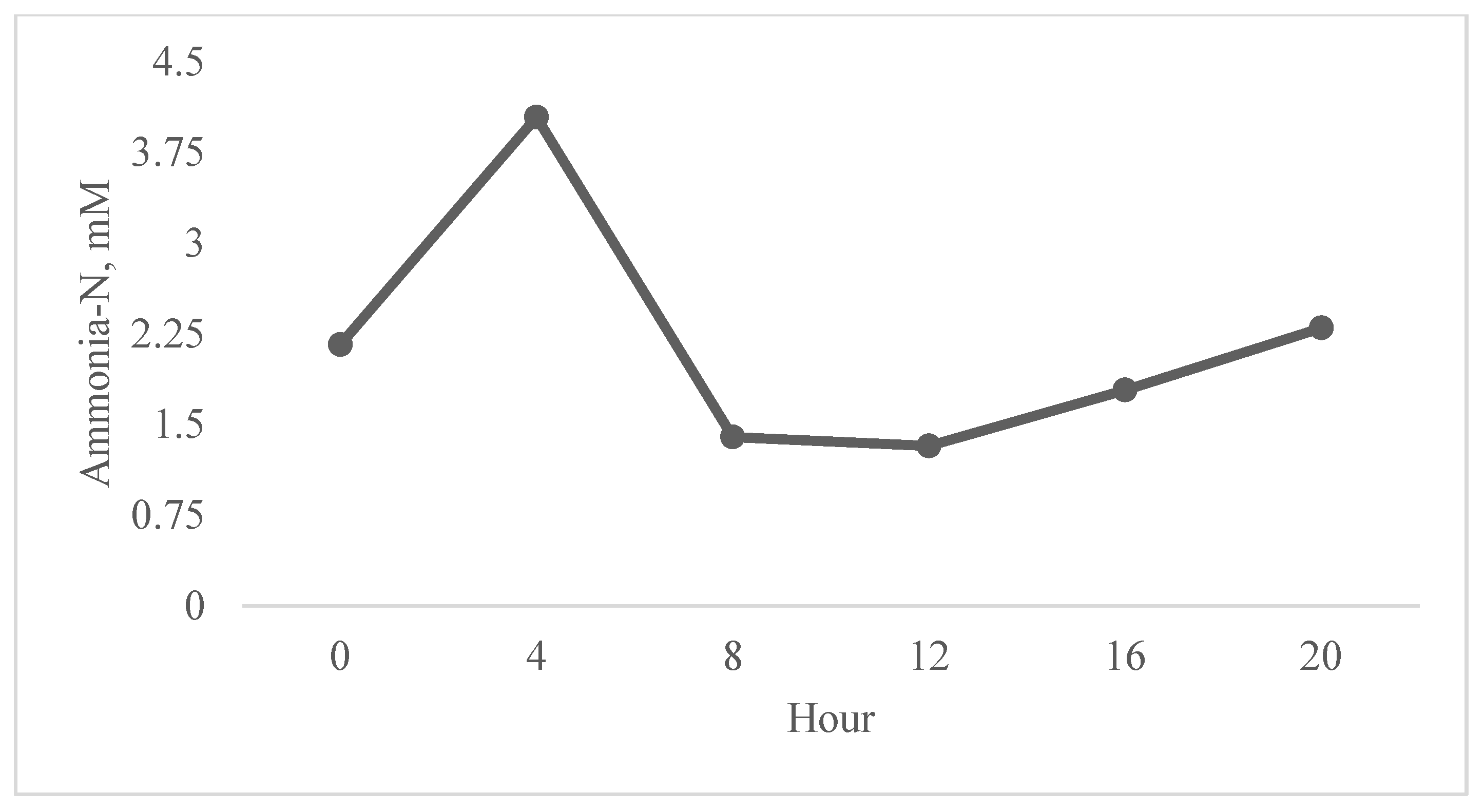

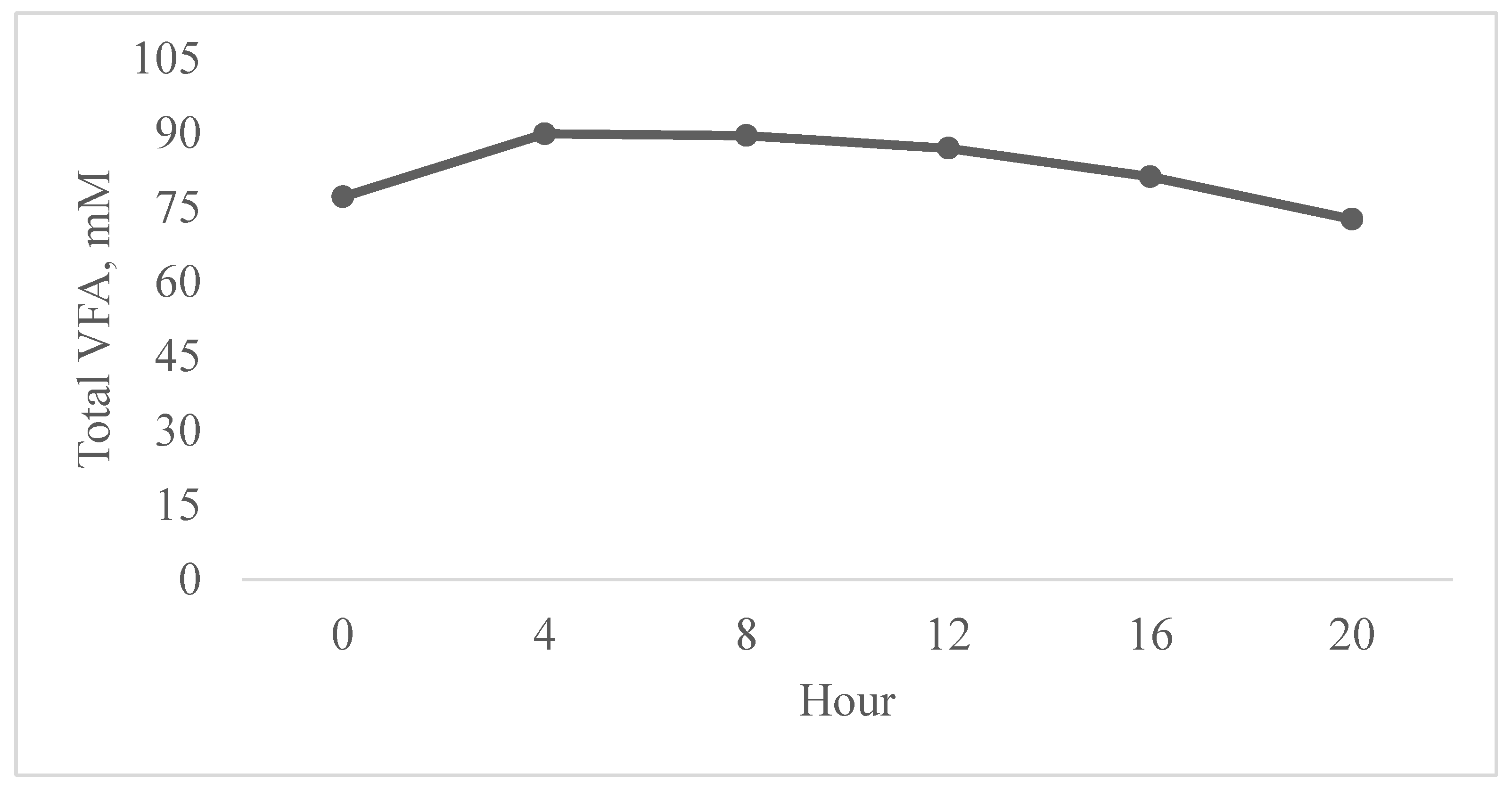

3.2. Experiment 2: Forage Utilization and Rumen Fermentation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mayista, A.; Sari, R.M.; Astuti, A.D.; Yasir, B.; Rumata, N.R.; Emran, T.B.; Nainu, F.; Simal-Gandara, J. Terpenes and terpenoids as main bioactive compounds of essential oils, their roles in human health and potential application as natural food preservatives. Food Chem. X 2022, 13, 100217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazaki, K.; Arimura, G.I.; Ohnishi, T. ‘Hidden’ terpenoids in plants: Their biosynthesis, localization and ecological roles. Plant Cell Physiol. 2017, 58, 1615–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, F.; Colombatto, D.; Brunetti, M.A.; Martinez, M.J.; Moreno, M.V.; Turcato, M.C.S.; Lucini, E.; Frossaco, G.; Ferrer, J.M. The reduction of methane production in the in vitro ruminal fermentation of different substrates is linked with the chemical composition of the essential oil. Animals 2020, 10, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miguel, M.G. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of essential oils: A short review. Molecules 2010, 15, 9252–9287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawidowicz, A.L.; Olszowy, M. Does antioxidant properties of the main component of essential oil reflect its antioxidant properties? The comparison of antioxidant properties of essential oils and their main components. Nat. Prod. Res. 2014, 28, 1952–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichling, J. Antiviral and virucidal properties of essential oils and isolated compounds—A scientific approach. Planta Medica 2022, 88, 587–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.R.; Wang, C.H.; Flores, N.J.C.; Su, Y.Y. Targeting open market with strategic business innovations: A case study of growth dynamics in essential oil and aromatherapy industry. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2019, 5, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poutaraud, A.; Antalik, A.M.; Plantureux, S. Grasslands: A source of secondary metabolites for livestock health. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 6535–6553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, L.E.; Benincasa, B.I.; Fachin, A.L.; Franca, S.C.; Contini, S.S.H.T.; Chagas, A.C.S.; Ana, C.S.; Beleboni, R.O. Thymus vulgaris L. essential oil and its main component thymol: Anthelmintic effects against Haemonchus contortus from sheep. Vet. Parasitol. 2016, 228, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paiano, R.B.; Bonilla, J.; de Sousa, R.L.M.; Moreno, A.M.; Baruselli, P.S. Chemical composition and antibacterial activity of essential oils against pathogens often related to cattle endometritis. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2020, 14, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.; Lei, Y.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, R.; Bai, Y.; Li, Z.; Jia, L.; Shi, J.; Cheng, Q.; Ma, Y.; et al. Dietary oregano essential oil supplementation alters meat quality, oxidative stability, and fatty acid profiles of beef cattle. Meat Sci. 2023, 205, 109317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrazco, A.V.; Peterson, C.B.; Zhao, Y.; Pan, Y.; McGlone, J.J.; DePeters, E.J.; Mitloehner, F.M. The impact of essential oil feed supplementation on enteric gas emissions and production parameters from dairy cattle. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakili, A.R.; Khorrami, B.; Mesgaran, M.D.; Parand, E. The effects of thyme and cinnamon essential oils on performance, rumen fermentation and blood metabolites in Holstein calves consuming high concentrate diet. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2013, 26, 935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Jia, M.; Fang, L.; Jiang, L.; Li, Y. Effects of eucalyptus oil and anise oil supplementation on rumen fermentation characteristics, methane emission, and digestibility in sheep. J. Anim. Sci. 2018, 96, 3460–3470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, P.; Liu, Z.B.; He, W.F.; Yu, S.B.; Gao, G.; Wang, J.K. Intermittent feeding of citrus essential oils as a potential strategy to decrease methane production by reducing microbial adaptation. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 194, 704–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khiaosa-ard, R.; Zebeli, Q. Meta-analysis of the effects of essential oils and their bioactive compounds on rumen fermentation characteristics and feed efficiency in ruminants. J. Anim. Sci. 2013, 91, 1819–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lupia, C.; Castagna, F.; Bava, R.; Naturale, M.D.; Zicarelli, L.; Marrelli, M.; Statti, G.; Tilocca, B.; Roncada, P.; Britti, D.; et al. Use of essential oils to counteract the phenomena of antimicrobial resistance in livestock species. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, J.R.; Innes, G.K.; Johnson, K.A.; Lhermie, G.; Ivanek, R.; Safi, A.G.; Lansing, D. Consumer perceptions of antimicrobial use in animal husbandry: A scoping review. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0270442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, T.S.; Fontoura, P.S.; Oliveira, A.; Rizzo, F.A.; Silveira, S.; Streck, A.F. Use of plant extracts and essential oils in the control of bovine mastitis. Res. Vet. Sci. 2020, 131, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershenzon, J.; Dudareva, N. The function of terpene natural products in the natural world. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2007, 3, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popova, M.P.; Chinou, I.B.; Marekov, I.N.; Bankova, V.S. Terpenes with antimicrobial activity from Cretan propolis. Phytochemistry 2009, 70, 1262–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffin, S.G.; Wyllie, S.G.; Markham, J.L.; Leach, D.N. The role of structure and molecular properties of terpenoids in determining their antimicrobial activity. Flavour. Frag. J. 1999, 14, 322–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benchaar, C.; Greathead, H. Essential oils and opportunities to mitigate enteric methane emissions from ruminants. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2011, 166–167, 338–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillejos, L.; Calsamiglia, S.; Ferret, A. Effect of essential oil active compounds on rumen microbial fermentation and nutrient flow in in vitro systems. J. Dairy Sci. 2006, 89, 2649–2658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, A.K.; Yu, Z. Effects of essential oils on methane production and fermentation by, and abundance and diversity of, rumen microbial populations. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 4271–4280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calsamiglia, S.; Busquet, M.; Cardozo, P.W.; Castillejos, L.; Ferret, A. Invited review: Essential oils as modifiers of rumen microbial fermentation. J. Dairy Sci. 2007, 90, 2580–2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ultee, A.; Bennik, M.H.; Moezelaar, R. The phenolic hydroxyl group of carvacrol is essential for action against the food-borne pathogen Bacillus cereus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 68, 1561–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, S. Essential oils: Their antibacterial properties and potential applications in foods—A review. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2004, 94, 223–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Cai, L.; Zhang, J.; Yang, A.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Guan, L.L.; Qi, D. Effects of thymol supplementation on goat rumen fermentation and rumen microbiota in vitro. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kissels, W.; Wu, X.; Santos, R.R. Interaction of the isomers carvacrol and thymol with the antibiotics doxycycline and tilmicosin: In vitro effects against pathogenic bacteria commonly found in the respiratory tract of calves. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 970–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamiri, M.J.; Azizabadi, E.; Momeni, Z.; Rezvani, M.R.; Atashi, H.; Akhlaghi, A. Effect of thymol and carvacrol on nutrient digestibility in rams fed high or low concentrate diets. Iran. J. Vet. Res. 2015, 16, 335–340. [Google Scholar]

- Benchaar, C. Diet supplementation with thyme oil and its main component thymol failed to favorably alter rumen fermentation, improve nutrient utilization, or enhance milk production in dairy cows. J. Dairy. Sci. 2021, 104, 324–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villalba, J.J.; Provenza, F.D. Learning and dietary choice in herbivores. Rangeland Ecol. Manage 2009, 62, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasci, K.D.; Wickersham, T.A.; Drewery, M.L. Acceptance and forage utilization responses of steers consuming low-quality forage and supplemented black soldier fly larvae as a novel feed. J. Anim. Sci. 2024, 102, skae168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorrami, B.; Vakili, A.R.; Mesgaran, M.D.; Klevenhusen, F. Thyme and cinnamon essential oils: Potential alternatives for monensin as a rumen modifier in beef production systems. Anim. Feed. Sci. Technol. 2015, 200, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huerta-Leidenz, N.O.; Cross, H.R.; Savell, J.W.; Lunt, D.K.; Baker, J.F.; Smith, S.B. Fatty acid composition of subcutaneous adipose tissue from male calves at different stages of growth. J. Anim. Sci. 1996, 74, 1256–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raun, N.S.; Burroughs, W. Suction strainer technique in obtaining rumen fluid samples from intact lambs. J. Anim. Sci. 1962, 21, 454–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goestch, A.L.; Galyean, M.L. Influence of feeding frequency on passage of fluid and particulate markers in steers fed a concentrate diet. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 1983, 63, 727–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broderick, G.A.; Kang, J.H. Automated simultaneous determination of ammonia and total amino acids in ruminal fluid and in vitro media. J. Dairy Sci. 1980, 63, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerth, C.R.; Berto, M.C.; Miller, R.K.; Savell, J.W. Cooking temperatures, steak thickness, and quality grade effects on volatile aroma compounds. Meat Muscle Biol. 2022, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, E.P.; Cox, J.R.; Wickersham, T.A.; Drewery, M.L. Evaluation of Black Soldier Fly larvae (Hermetia illucens) as a protein supplement for beef steers consuming low-quality forage. Transl. Anim. Sci. 2022, 6, txac018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.; Liu, J.; Cai, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Wang, L.; Yang, W.; Huang, B. The volatile organic compounds and palatability of mixed ensilage of marigold (Tagetes erecta L.) crop residues. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benetel, G.; Silva, T.D.S.; Fagundes, G.M.; Welter, K.C.; Melo, F.A.; Lobo, A.A.; Muir, J.P.; Bueno, I.C. Essential oils as in vitro ruminal fermentation manipulators to mitigate methane emission by beef cattle grazing tropical grasses. Molecules 2022, 27, 2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.D.; Martin, S.A. Effects of thymol on ruminal microorganisms. Curr. Microbiol. 2000, 41, 336–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, J.B. Rumen. In Encyclopedia of Microbiology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009; pp. 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McSweeney, C.S.; Palmer, B.; McNeill, D.M.; Krause, D.O. Microbial interactions with tannins: Nutritional consequences for ruminants. Anim. Feed. Sci. Technol. 2001, 91, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slyter, L.L.; Satter, L.D.; Dinius, D.A. Effect of ruminal ammonia concentration on nitrogen utilization by steers. J. Anim. Sci. 1979, 48, 906–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greathead, H. Plants and plant extracts for improving animal productivity. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2003, 62, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, E.N. Energy contributions of volatile fatty acids from the gastrointestinal tract in various species. Physiol. Rev. 1990, 70, 567–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardozo, P.W.; Calsamiglia, S.; Ferret, A.; Kamel, C. Screening for the effects of natural plant extracts at different pH on in vitro rumen microbial fermentation of a high-concentrate diet for beef cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 2005, 83, 2572–2579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, B.R.; Parker, D.; Brauer, D.; Waldrip, H.; Lockard, C.; Hales, K.; Akbay, A.; Augyte, S. The role of seaweed as a potential dietary supplementation for enteric methane mitigation in ruminants: Challenges and opportunities. Anim. Nutr. 2021, 7, 371–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, C.P.; Beck, P.A.; Gadberry, M.S.; Hess, T.; Hubbell, D., III. Effects of monensin dose from a self-fed mineral supplement on performance of growing beef steers on forage-based diets. Appl. Anim. Sci. 2020, 36, 515–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juven, B.J.; Kanner, J.; Schved, F.; Weisslowicz, H. Factors that interact with the antibacterial action of thyme essential oil and its active constituents. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 1994, 76, 626–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Experiment 1: Chemical composition, %DM 1 | |||

| Item | Hay | Alfalfa cubes | Cottonseed meal |

| OM | 90.4 | 89.0 | 93.1 |

| NDF | 75.6 | 46.2 | 35.3 |

| ADF | 43.3 | 34.6 | 24.0 |

| CP | 7.20 | 18.4 | 43.0 |

| Experiment 2: Chemical composition, % DM | |||

| Hay | Alfalfa cubes | --- | |

| OM | 89.6 | 86.7 | --- |

| NDF | 69.9 | 35.4 | --- |

| ADF | 49.3 | 27.8 | --- |

| CP | 3.44 | 17.9 | --- |

| Calcium | 0.35 | 1.71 | --- |

| Phosphorus | 0.04 | 0.24 | --- |

| Potassium | 1.27 | 2.87 | --- |

| Treatment | Treatment Intake, kg/d 2 | Hay Intake, kg/d 3 |

|---|---|---|

| 0 mg thymol/kg forage intake | 1.14 | 9.78 |

| 110 mg thymol/kg forage intake | 1.10 | 9.99 |

| 220 mg thymol/kg forage intake | 1.11 | 10.1 |

| 330 mg thymol/kg forage intake | 1.06 | 9.25 |

| Treatment | Contrast p-Values | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CON 1 | 120-T | 240-T | 480-T | SEM | Linear | Quadratic | |

| n | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | |||

| OM intake, kg/d 2 | |||||||

| Forage | 4.48 | 4.58 | 4.63 | 4.74 | 0.31 | 0.87 | 0.55 |

| Supplement | 1.01 | 1.02 | 1.07 | 1.09 | 0.07 | 0.96 | 0.23 |

| Total | 5.49 | 5.59 | 5.70 | 5.82 | 0.38 | 0.89 | 0.47 |

| Digestible | 3.15 | 3.01 | 3.24 | 3.32 | 0.18 | 0.54 | 0.31 |

| Total tract digestion, % | |||||||

| DMD | 53.2 | 49.3 | 52.3 | 53.0 | 2.86 | 0.22 | 0.52 |

| OMD | 57.8 | 54.4 | 56.8 | 57.8 | 2.81 | 0.28 | 0.57 |

| NDFD | 64.0 | 60.7 | 62.1 | 65.3 | 2.49 | 0.19 | 0.51 |

| Treatment 1 | Contrast p-Values | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CON | 120-T | 240-T | 480-T | SEM | Linear | Quadratic | |

| n | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | |||

| Ammonia-N, mM | 2.42 | 1.87 | 2.10 | 2.28 | 0.21 | 0.83 | 0.09 |

| Total VFA 2, mM | 81.9 | 84.9 | 80.2 | 84.7 | 3.55 | 0.83 | 0.83 |

| Molar proportions, % | |||||||

| Acetate | 74.8 | 74.9 | 75.4 | 75.0 | 0.14 | 0.04 | 0.08 |

| Propionate | 14.5 | 14.4 | 14.1 | 14.4 | 0.17 | 0.33 | 0.09 |

| Butyrate | 8.40 | 8.30 | 8.30 | 8.30 | 0.17 | 0.46 | 0.74 |

| Isobutyrate | 1.10 | 1.10 | 1.10 | 1.10 | 0.02 | 0.90 | 0.79 |

| Valerate | 0.60 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.02 | 0.12 | 0.52 |

| Isovalerate | 0.70 | 0.70 | 0.60 | 0.70 | 0.03 | 0.32 | 0.85 |

| Acetate: Propionate | 5.18 | 5.20 | 5.38 | 5.21 | 0.07 | 0.21 | 0.05 |

| pH | 6.59 | 6.59 | 6.63 | 6.61 | 0.04 | 0.62 | 0.83 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fukuda, E.P.; Suter, J.P.; Jessup, R.W.; Drewery, M.L. Diet Acceptance and Utilization Responses to Increasing Doses of Thymol in Beef Steers Consuming Forage. Animals 2025, 15, 3637. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243637

Fukuda EP, Suter JP, Jessup RW, Drewery ML. Diet Acceptance and Utilization Responses to Increasing Doses of Thymol in Beef Steers Consuming Forage. Animals. 2025; 15(24):3637. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243637

Chicago/Turabian StyleFukuda, Emma P., Jordan P. Suter, Russell W. Jessup, and Merritt L. Drewery. 2025. "Diet Acceptance and Utilization Responses to Increasing Doses of Thymol in Beef Steers Consuming Forage" Animals 15, no. 24: 3637. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243637

APA StyleFukuda, E. P., Suter, J. P., Jessup, R. W., & Drewery, M. L. (2025). Diet Acceptance and Utilization Responses to Increasing Doses of Thymol in Beef Steers Consuming Forage. Animals, 15(24), 3637. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243637