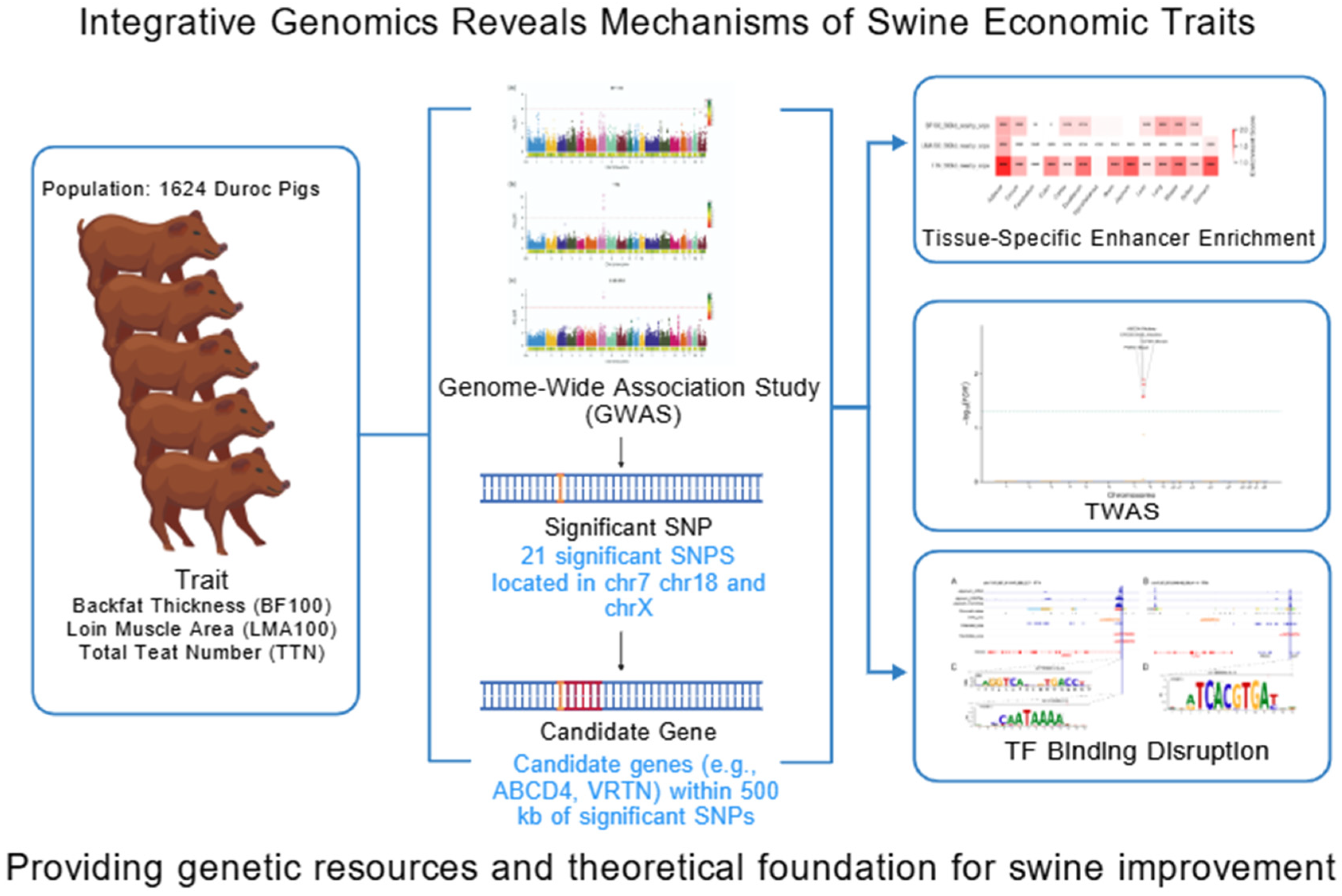

Integrative Multi-Omics Analysis Unveils Candidate Genes and Functional Variants for Growth and Reproductive Traits in Duroc Pigs

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection and Phenotyping

2.1.1. Animal Population and Phenotypic Measurements

2.1.2. Genotyping and Data Processing

2.2. Genome-Wide Association Study (GWAS)

2.2.1. Genotype Data Quality Control and Population Structure Analysis

2.2.2. Association Analysis

2.3. SNP Enrichment Analysis

2.4. Candidate Gene Identification and Functional Annotation

2.5. TWAS Analysis

2.6. Identification of Candidate Regulatory Variants

2.7. TF Motif Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Phenotypic and Genotypic Data Summary

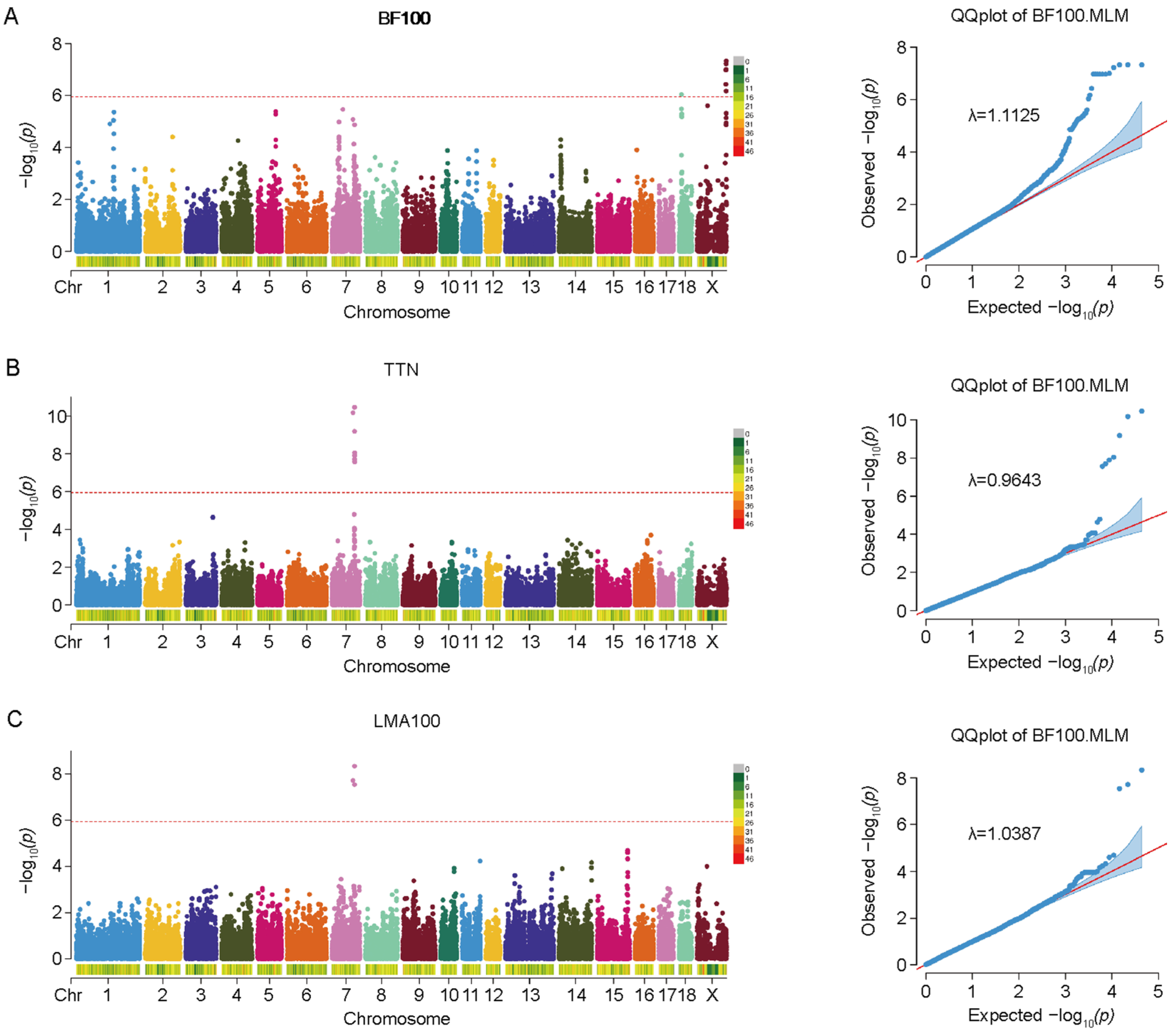

3.2. Genome-Wide Association Analysis (GWAS) of BF100, LMA100, and TTN

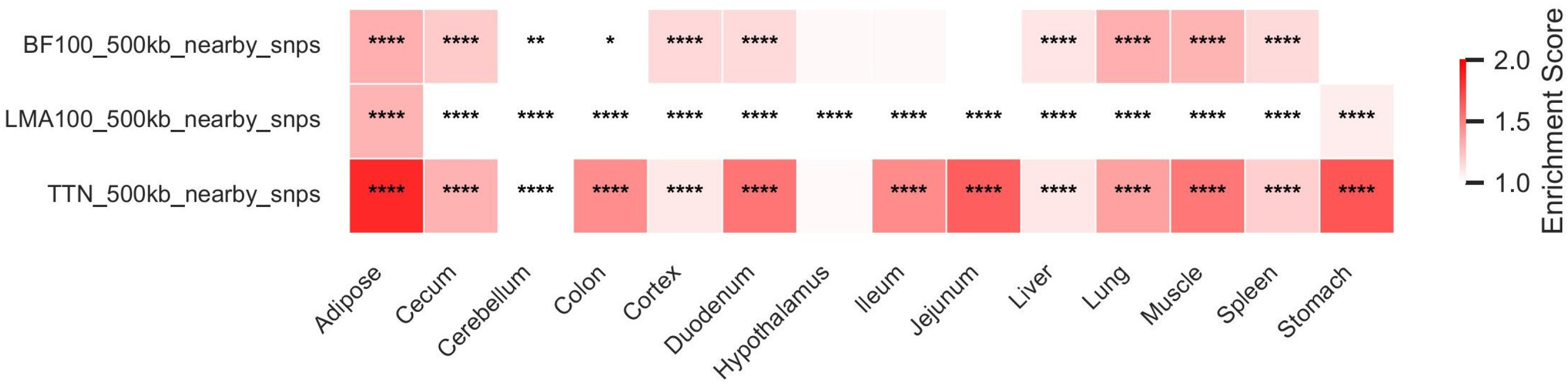

3.3. Enrichment Analysis of Trait-Associated SNPs

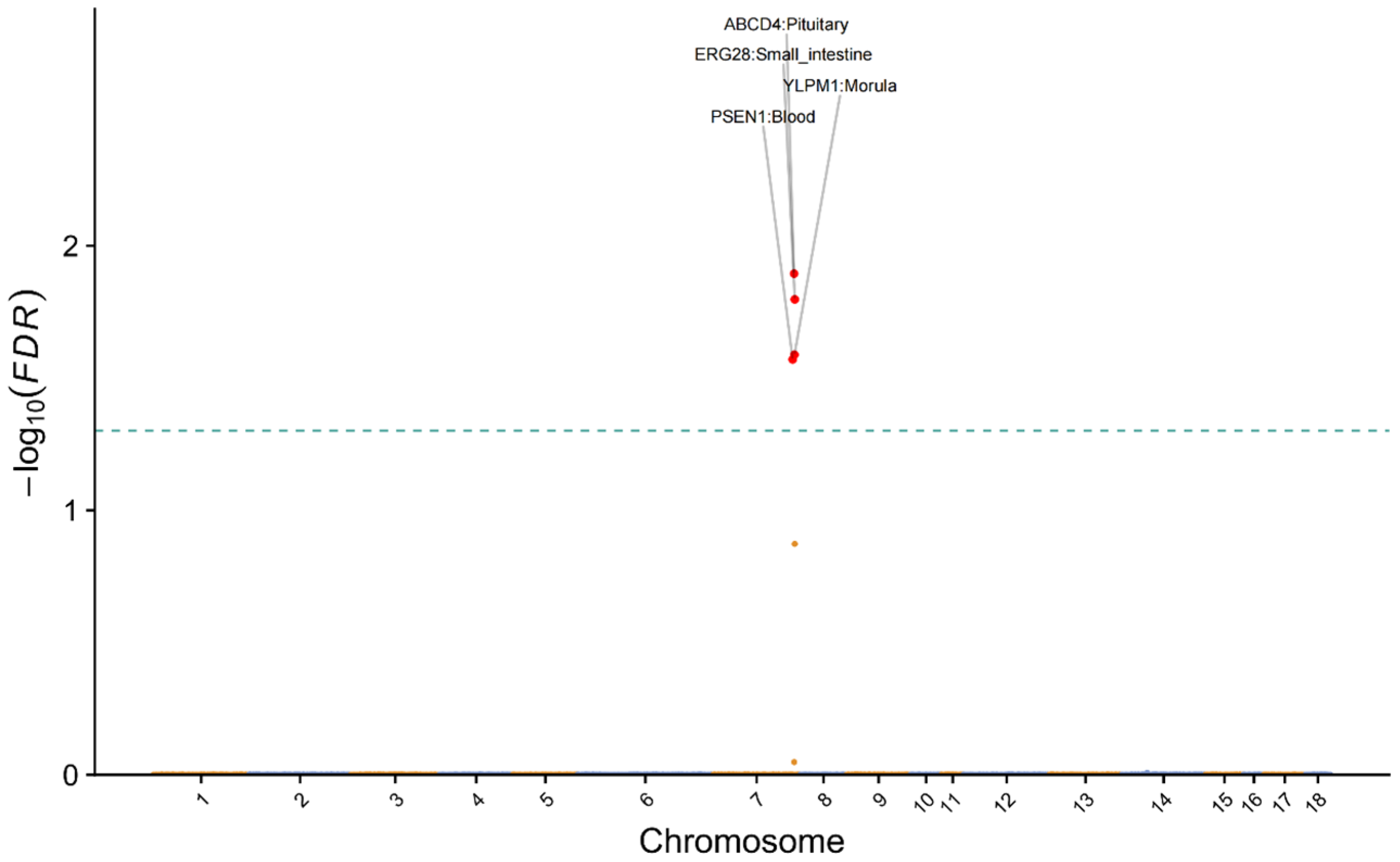

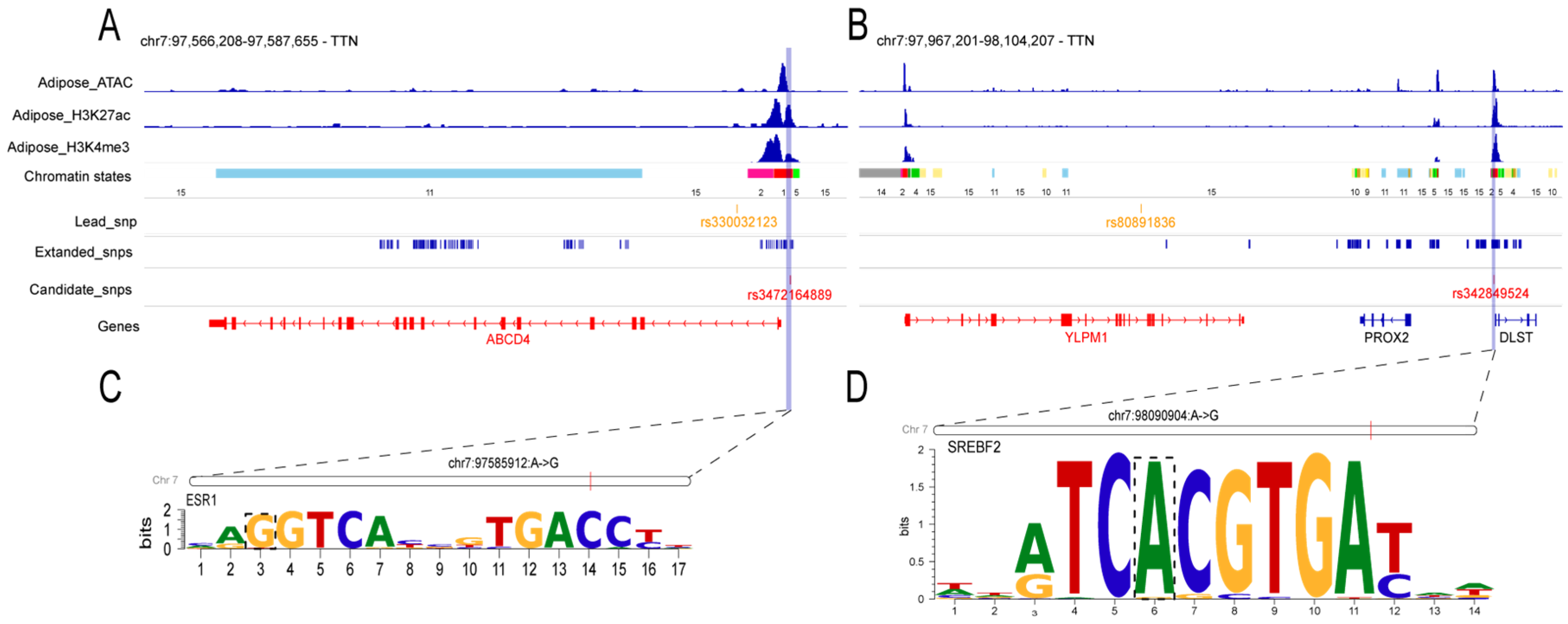

3.4. TWAS Reveals Functional Genes and Underlying Regulatory Variants for TTN

3.5. Functional Enrichment Analysis of Candidate Target Genes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gozalo-Marcilla, M.; Buntjer, J.; Johnsson, M.; Batista, L.; Diez, F.; Werner, C.R.; Chen, C.-Y.; Gorjanc, G.; Mellanby, R.J.; Hickey, J.M.; et al. Genetic Architecture and Major Genes for Backfat Thickness in Pig Lines of Diverse Genetic Backgrounds. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2021, 53, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, Z.B.; Nugent, R.A., III. Heritability of Body Length and Measures of Body Density and Their Relationship to Backfat Thickness and Loin Muscle Area in Swine. J. Anim. Sci. 2003, 81, 1943–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Z.; Li, S.; Ding, R.; Yang, M.; Zheng, E.; Yang, H.; Gu, T.; Xu, Z.; Cai, G.; Wu, Z.; et al. Meta-Analysis of Genome-Wide Association Studies for Loin Muscle Area and Loin Muscle Depth in Two Duroc Pig Populations. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0218263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, R.; Chen, L.; Liu, X.; Liu, H.; Shi, G.; Hou, X.; Zhang, R.; Yang, M.; Niu, N.; Wang, L.; et al. Integrating Genome-Wide Association Study with RNA-Sequencing Reveals HDAC9 as a Candidate GeneInfluencing Loin Muscle Area in Beijing Black Pigs. Biology 2022, 11, 1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bovo, S.; Ballan, M.; Schiavo, G.; Ribani, A.; Tinarelli, S.; Utzeri, V.J.; Dall’Olio, S.; Gallo, M.; Fontanesi, L. Single-Marker and Haplotype-Based Genome-Wide Association Studies for the Number of Teats in Two Heavy Pig Breeds. Anim. Genet. 2021, 52, 440–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscatelli, G.; Dall’Olio, S.; Bovo, S.; Schiavo, G.; Kazemi, H.; Ribani, A.; Zambonelli, P.; Tinarelli, S.; Gallo, M.; Bertolini, F.; et al. Genome-Wide Association Studies for the Number of Teats and Teat Asymmetry Patterns in Large White Pigs. Anim. Genet. 2020, 51, 595–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaalberg, R.M.; Chu, T.T.; Bovbjerg, H.; Jensen, J.; Villumsen, T.M. Genetic Parameters for Early Piglet Weight, Litter Traits and Number of Functional Teats in Organic Pigs. Animal 2023, 17, 100717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdellaoui, A.; Yengo, L.; Verweij, K.J.H.; Visscher, P.M. 15 Years of GWAS Discovery: Realizing the Promise. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2023, 110, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, R.; Zhuang, Z.; Qiu, Y.; Wang, X.; Wu, J.; Zhou, S.; Ruan, D.; Xu, C.; Hong, L.; Gu, T.; et al. A Composite Strategy of Genome-Wide Association Study and Copy Number Variation Analysis for Carcass Traits in a Duroc Pig Population. BMC Genom. 2022, 23, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhou, J.; Chen, C.J.; Zhang, J.; Wen, W.; Tian, J.; Zhang, Z.; Gu, Y. GWAS-Based Identification of New Loci for Milk Yield, Fat, and Protein in Holstein Cattle. Animals 2020, 10, 2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, M.I.; Abecasis, G.R.; Cardon, L.R.; Goldstein, D.B.; Little, J.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Hirschhorn, J.N. Genome-Wide Association Studies for Complex Traits: Consensus, Uncertainty and Challenges. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2008, 9, 356–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.; Ruan, G.R.; Su, Y.; Xiao, S.J.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Ren, J.; Ding, N.S.; Huang, L.S. Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies QTLs for EBV of Backfat Thickness and Average Daily Gain in Duroc Pigs. Genetika 2015, 51, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.; Do, K.-T.; Park, K.-D.; Lee, H.-K. Genome-Wide Association Study Using a Single-Step Approach for Teat Number in Duroc, Landrace and Yorkshire Pigs in Korea. Anim. Genet. 2023, 54, 743–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurano, M.T.; Humbert, R.; Rynes, E.; Thurman, R.E.; Haugen, E.; Wang, H.; Reynolds, A.P.; Sandstrom, R.; Qu, H.; Brody, J.; et al. Systematic Localization of Common Disease-Associated Variation in Regulatory DNA. Science 2012, 337, 1190–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Ritchie, M.D. From GWAS to Gene: Transcriptome-Wide Association Studies and Other Methods to Functionally Understand GWAS Discoveries. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 713230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orozco, G.; Schoenfelder, S.; Walker, N.; Eyre, S.; Fraser, P. 3D Genome Organization Links Non-Coding Disease-Associated Variants to Genes. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 995388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Z.; Yao, Y.; Yin, H.; Cai, Z.; Wang, Y.; Bai, L.; Kern, C.; Halstead, M.; Chanthavixay, G.; Trakooljul, N.; et al. Pig Genome Functional Annotation Enhances the Biological Interpretation of Complex Traits and Human Disease. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, M.; Li, Z.; Yang, X.; Li, K.; Xie, A.; Dong, F.; Wang, S.; Yan, J.; Liu, J. An Overview of Detecting Gene-Trait Associations by Integrating GWAS Summary Statistics and eQTLs. Sci. China Life Sci. 2024, 67, 1133–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, M.; Chen, K.; Zhang, S.; Tian, M.; Shen, Y.; Cao, C.; Gu, N. Multiome-Wide Association Studies: Novel Approaches for Understanding Diseases. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2024, 22, qzae077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Teng, J.; Liu, S.; Lin, Q.; Wu, J.; Gao, Y.; Bai, Z.; FarmGTEx Consortium; Li, B.; et al. FarmGTEx TWAS-Server: An Interactive Web Server for Customized TWAS Analysis. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2025, 23, qzaf006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, M.; Ruan, D.; Qiu, Y.; Ye, Y.; Zhou, S.; Yang, J.; Sun, Y.; Ma, F.; Wu, Z.; Yang, J.; et al. Genome-Wide Association Study for Loin Muscle Area of Commercial Crossbred Pigs. Anim. Biosci. 2023, 36, 861–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Pu, L.; Shi, L.; Gao, H.; Zhang, P.; Wang, L.; Zhao, F. Revealing New Candidate Genes for Teat Number Relevant Traits in Duroc Pigs Using Genome-Wide Association Studies. Animals 2021, 11, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, S.; Li, H.; Zhang, L.; Mu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, T.; Wu, J.; Tang, H.; Zheng, S.; Liu, Y.; et al. Generic Diagramming Platform (GDP): A Comprehensive Database of High-Quality Biomedical Graphics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D1670–D1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Na, C.-S. Weighted Single-Step Genome-Wide Association Study to Reveal New Candidate Genes for Productive Traits of Landrace Pig in Korea. J. Anim. Sci. Technol. 2024, 66, 702–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, K.; Irie, M.; Kadowaki, H.; Shibata, T.; Kumagai, M.; Nishida, A. Genetic Parameter Estimates of Meat Quality Traits in Duroc Pigs Selected for Average Daily Gain, Longissimus Muscle Area, Backfat Thickness, and Intramuscular Fat Content. J. Anim. Sci. 2005, 83, 2058–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, K.; Kadowaki, H.; Shibata, T.; Uchida, H.; Nishida, A. Selection for Daily Gain, Loin-Eye Area, Backfat Thickness and Intramuscular Fat Based on Desired Gains over Seven Generations of Duroc Pigs. Livest. Prod. Sci. 2005, 97, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NY/T 2894-2016; Measurement of Backfat Depth and Loin Muscle Area on Living Pig with B-Mode Ultrasound, China. China Agriculture Press: Beijing, China, 2016.

- Li, L.-Y.; Xiao, S.-J.; Tu, J.-M.; Zhang, Z.-K.; Zheng, H.; Huang, L.-B.; Huang, Z.-Y.; Yan, M.; Liu, X.-D.; Guo, Y.-M. A Further Survey of the Quantitative Trait Loci Affecting Swine Body Size and Carcass Traits in Five Related Pig Populations. Anim. Genet. 2021, 52, 621–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinlan, A.R.; Hall, I.M. BEDTools: A Flexible Suite of Utilities for Comparing Genomic Features. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 841–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Lee, S.H.; Goddard, M.E.; Visscher, P.M. GCTA: A Tool for Genome-Wide Complex Trait Analysis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2011, 88, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Zhang, H.; Tang, Z.; Xu, J.; Yin, D.; Zhang, Z.; Yuan, X.; Zhu, M.; Zhao, S.; Li, X.; et al. rMVP: A Memory-Efficient, Visualization-Enhanced, and Parallel-Accelerated Tool for Genome-Wide Association Study. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2021, 19, 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Xiang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Qi, X.; Zheng, Z.; Zhou, P.; Tang, Z.; Jin, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Fu, Y.; et al. Enhancer-Promoter Interaction Maps Provide Insights into Skeletal Muscle-Related Traits in Pig Genome. BMC Biol. 2022, 20, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heger, A.; Webber, C.; Goodson, M.; Ponting, C.P.; Lunter, G. GAT: A Simulation Framework for Testing the Association of Genomic Intervals. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 2046–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Teng, J.; Lin, Q.; Bai, Z.; Liu, S.; Guan, D.; Li, B.; Gao, Y.; Hou, Y.; Gong, M.; et al. The Farm Animal Genotype-Tissue Expression (FarmGTEx) Project. Nat. Genet. 2025, 57, 786–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, J.; Gao, Y.; Yin, H.; Bai, Z.; Liu, S.; Zeng, H.; Bai, L.; Cai, Z.; Zhao, B.; Li, X.; et al. A Compendium of Genetic Regulatory Effects across Pig Tissues. Nat. Genet. 2024, 56, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coetzee, S.G.; Coetzee, G.A.; Hazelett, D.J. motifbreakR: An R/Bioconductor Package for Predicting Variant Effects at Transcription Factor Binding Sites. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 3847–3849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Gao, J.; Yang, J.; Wu, Z.; Fan, Y.; Xing, Y.; Li, L.; Xiao, S.; et al. VRTN is Required for the Development of Thoracic Vertebrae in Mammals. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2018, 14, 667–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, M.; Huang, J.; Wang, K.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, H.; Wang, F.; Han, J. Functional Mutations in the VRTN Gene Influence Growth Traits and Meat Quality in Hainan Black Goats. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hannan, F.M.; Elajnaf, T.; Vandenberg, L.N.; Kennedy, S.H.; Thakker, R.V. Hormonal Regulation of Mammary Gland Development and Lactation. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2023, 19, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitai, K.; Kawaguchi, K.; Tomohiro, T.; Morita, M.; So, T.; Imanaka, T. The Lysosomal Protein ABCD4 Can Transport Vitamin B12 across Liposomal Membranes In Vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 296, 100654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boachie, J.; Adaikalakoteswari, A.; Samavat, J.; Saravanan, P. Low Vitamin B12 and Lipid Metabolism: Evidence from Pre-Clinical and Clinical Studies. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, A.L.; Altamirano, G.A.; Leturia, J.; Bosquiazzo, V.L.; Muñoz-de-Toro, M.; Kass, L. Male Mammary Gland Development and Methylation Status of Estrogen Receptor Alpha in Wistar Rats Are Modified by the Developmental Exposure to a Glyphosate-Based Herbicide. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2019, 481, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blalock, W.L.; Piazzi, M.; Bavelloni, A.; Raffini, M.; Faenza, I.; D’Angelo, A.; Cocco, L. Identification of the PKR Nuclear Interactome Reveals Roles in Ribosome Biogenesis, mRNA Processing and Cell Division. J. Cell. Physiol. 2014, 229, 1047–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bommer, G.T.; MacDougald, O.A. Regulation of Lipid Homeostasis by the Bifunctional SREBF2-miR33a Locus. Cell Metab. 2011, 13, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.-M.; Karhunen, P.J.; Levula, M.; Ilveskoski, E.; Mikkelsson, J.; Kajander, O.A.; Järvinen, O.; Oksala, N.; Thusberg, J.; Vihinen, M.; et al. Expression of Sterol Regulatory Element-Binding Transcription Factor (SREBF) 2 and SREBF Cleavage-Activating Protein (SCAP) in Human Atheroma and the Association of Their Allelic Variants with Sudden Cardiac Death. Thromb. J. 2008, 6, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, T.; Peng, D.; Bu, G.; Gu, H.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, R.; Zhou, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Lei, M. Transcriptional Regulation Analysis of FAM3A Gene and Its Effect on Adipocyte Differentiation. Gene 2016, 595, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibragimov, E.; Pedersen, A.Ø.; Sloth, N.M.; Fredholm, M.; Karlskov-Mortensen, P. Identification of a Novel QTL for Lean Meat Percentage Using Imputed Genotypes. Anim. Genet. 2024, 55, 658–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Zhao, C.; Yang, R.; Wang, Y.; Hu, X. ABCD4 Is Associated with Mammary Gland Development in Mammals. BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Trait | Effective Record Count | Mean | Standard Deviation | Maximum | Minimum | Coefficient of Variation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BF100 (cm) | 1546 | 9.74 | 1.86 | 20.30 | 5.38 | 19.11 |

| LMA100 (cm2) | 1546 | 49.49 | 10.61 | 71.64 | 25.76 | 21.43 |

| TTN | 1235 | 13.64 | 1.06 | 16.00 | 10.00 | 7.74 |

| Traits | SNP ID | Chrom | Position | p-Value | Candidate Genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BF100 | rs81236473 | 18 | 10555467 | 9.34 × 10−7 | ZC3HAV1L |

| rs81333323 | X | 123188729 | 3.72 × 10−7 | CNGA2\GABRE | |

| rs332246267 | X | 123225920 | 1.06 × 10−7 | CNGA2\GABRE | |

| rs329206246 | X | 123251807 | 1.06 × 10−7 | CNGA2\GABRE | |

| rs336224043 | X | 123302262 | 1.06 × 10−7 | CNGA2\GABRE | |

| rs334203110 | X | 123655172 | 1.06 × 10−7 | GABRA3 | |

| rs320267534 | X | 123827689 | 1.06 × 10−7 | BGN/SLC6A8 | |

| rs80918182 | X | 123849200 | 1.06 × 10−7 | BGN/SLC6A8 | |

| rs330196368 | X | 123955387 | 9.97 × 10−8 | BGN/SLC6A8 | |

| rs326373823 | X | 124344831 | 6.02 × 10−8 | BGN/SLC6A8 | |

| rs81245332 | X | 124482822 | 6.78 × 10−7 | BGN/SLC6A8 | |

| rs330863063 | X | 124702511 | 4.72 × 10−8 | SLC6A8/FAM3A | |

| rs327767193 | X | 125021305 | 4.72 × 10−8 | FAM3A | |

| rs344761734 | X | 125135139 | 4.72 × 10−8 | FAM3A | |

| LMA100/TTN | / | 7 | 91308348 | 1.93 × 10−8 | PIGH |

| rs330032123 | 7 | 97584287 | 2.91 × 10−8 | PTGR2/FAM161B/LIN52/ABCD4/VRTN/SYNDIG1L/LTBP2/AREL1/YLPM1/PROX2 | |

| rs711580469 | 7 | 97622770 | 4.54 × 10−9 | PTGR2/FAM161B/LIN52/ABCD4/VRTN/SYNDIG1L/LTBP2/AREL1/YLPM1/PROX2/DLST | |

| TTN | rs81396056 | 7 | 97732109 | 1.95 × 10−8 | ABCD4/NPC2/VRTN/SYNDIG1L/LTBP2/AREL1/YLPM1/PROX2/DLST |

| rs80891836 | 7 | 98022168 | 1.25 × 10−8 | ABCD4/NPC2/VRTN/SYNDIG1L/LTBP2/AREL1/YLPM1/PROX2/DLST | |

| rs80836267 | 7 | 98089286 | 8.95 × 10−9 | VRTN/SYNDIG1L/LTBP2/AREL1/YLPM1/PROX2/DLST | |

| rs336641062 | 7 | 98116120 | 2.68 × 10−8 | VRTN/RPS6KL1/SYNDIG1L/LTBP2/AREL1/YLPM1/PROX2/DLST |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yan, Z.; Li, X.; Yang, W.; Zhou, P.; Zhang, W.; Li, X.; Fu, L.; Li, J.; Du, X. Integrative Multi-Omics Analysis Unveils Candidate Genes and Functional Variants for Growth and Reproductive Traits in Duroc Pigs. Animals 2025, 15, 3627. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243627

Yan Z, Li X, Yang W, Zhou P, Zhang W, Li X, Fu L, Li J, Du X. Integrative Multi-Omics Analysis Unveils Candidate Genes and Functional Variants for Growth and Reproductive Traits in Duroc Pigs. Animals. 2025; 15(24):3627. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243627

Chicago/Turabian StyleYan, Zhuofan, Xiyue Li, Wenbo Yang, Peng Zhou, Weiya Zhang, Xinyun Li, Liangliang Fu, Jingjin Li, and Xiaoyong Du. 2025. "Integrative Multi-Omics Analysis Unveils Candidate Genes and Functional Variants for Growth and Reproductive Traits in Duroc Pigs" Animals 15, no. 24: 3627. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243627

APA StyleYan, Z., Li, X., Yang, W., Zhou, P., Zhang, W., Li, X., Fu, L., Li, J., & Du, X. (2025). Integrative Multi-Omics Analysis Unveils Candidate Genes and Functional Variants for Growth and Reproductive Traits in Duroc Pigs. Animals, 15(24), 3627. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243627