Evaluation of Seaweed-Based Feed Additive on Enteric Methane Emissions of Grazing Heifers

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal Selection and Management

2.2. GreenFeed Emissions Monitoring Configuration

2.3. Baseline Data Collection

2.4. Seaweed-Based Feed Additive Supplementation and Experimental Design

2.5. Residual Effects from Removal of Seaweed-Based Feed Additive

2.6. Bromoform Measurement

- A 20 mL glass vial was used in the headspace autosampler and heated to 160 °C for 3 min. Nitrogen gas (Air Liquide Canada, Montreal, QC, Canada, 99.999% purity) was used to pressurize the vial.

- The gas chromatograph was equipped with a DB-624 column (UI 60 m × 0.32 mm × 1.80 µm) and operated with a split ratio of 20:1 with helium (Air Liquide Canada, Montreal, QC, Canada, 99.9999% purity) as the carrying gas.

- The oven temperature was programmed as follows: initial hold at 40 °C for 1 min, followed by an increase to 200 °C at a rate of 30 °C/min, with a final hold for 4 min.

- The mass spectrometer operated with a selected ion monitoring (SIM) mode at m/z 173 and 252, with a dwell time of 50 ms per ion.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

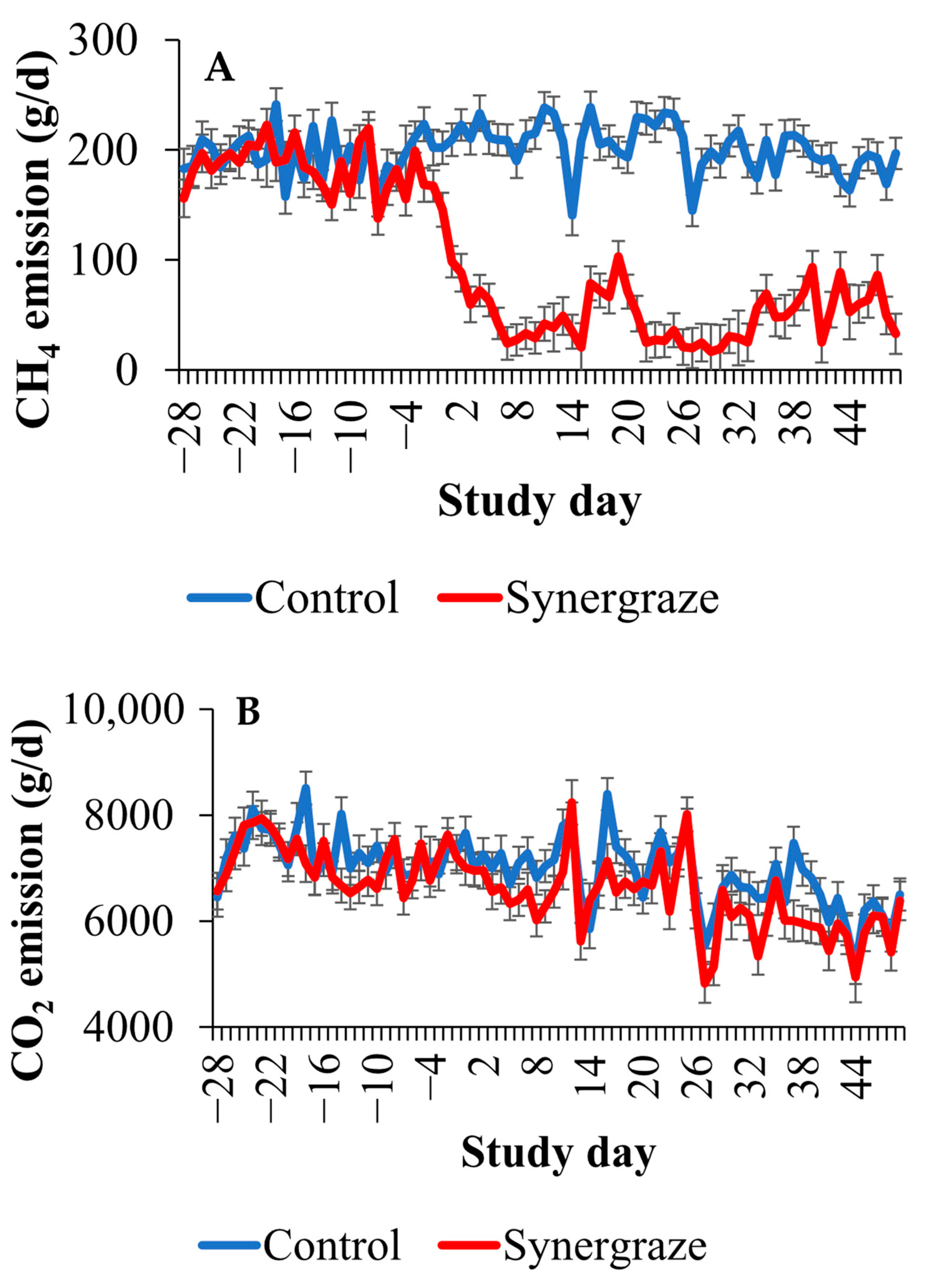

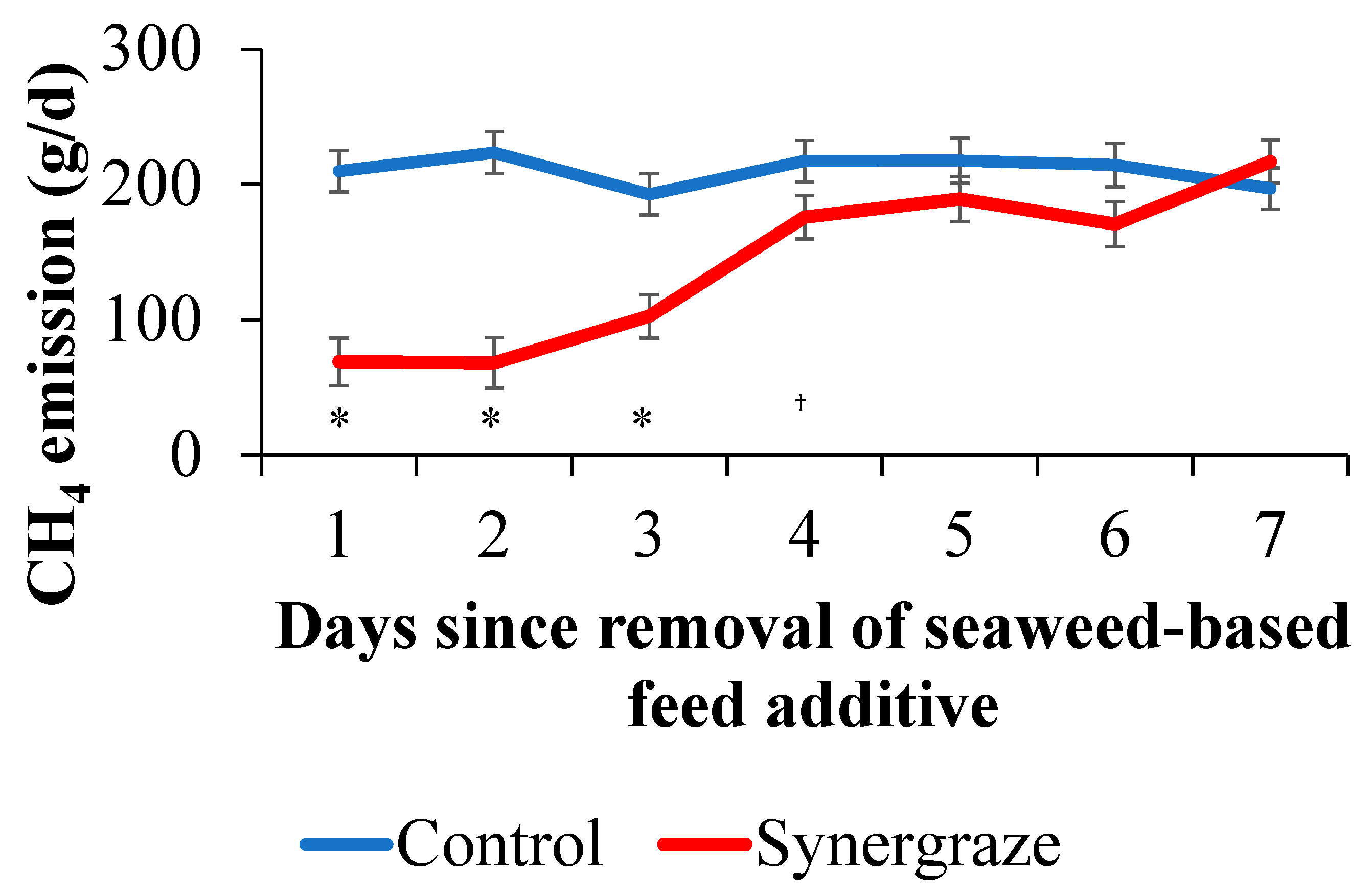

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MCR | Methyl-coenzyme M reductase |

| SBFA | Seaweed-based feed additive |

| GHG | Greenhouse gas |

| GEM | GreenFeed emission monitoring |

| CH4 | Methane |

| 3-NOP | 3-nitrooxypropanol |

| CHBr3 | Bromoform |

References

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Livestock and Enteric Methane. Available online: https://www.fao.org/in-action/enteric-methane/en (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Patra, A.K.; Puchala, R. Methane Mitigation in Ruminants with Structural Analogues and Other Chemical Compounds Targeting Archaeal Methanogenesis Pathways. Biotechnol. Adv. 2023, 69, 108268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roques, S.; Martinez-Fernandez, G.; Ramayo-Caldas, Y.; Popova, M.; Denman, S.; Meale, S.J.; Morgavi, D.P. Recent Advances in Enteric Methane Mitigation and the Long Road to Sustainable Ruminant Production. Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci. 2024, 12, 321–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinley, R.D.; Martinez-Fernandez, G.; Matthews, M.K.; de Nys, R.; Magnusson, M.; Tomkins, N.W. Mitigating the Carbon Footprint and Improving Productivity of Ruminant Livestock Agriculture Using a Red Seaweed. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 259, 120836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P.; Li, D.; Yang, Q.; Su, P.; Wang, H.; Heimann, K.; Zhang, W. Commercial Cultivation, Industrial Application, and Potential Halocarbon Biosynthesis Pathway of Asparagopsis Sp. Algal Res. 2021, 56, 102319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camer-Pesci, B.; Laird, D.W.; van Keulen, M.; Vadiveloo, A.; Chalmers, M.; Moheimani, N.R. Opportunities of Asparagopsis Sp. Cultivation to Reduce Methanogenesis in Ruminants: A Critical Review. Algal Res. 2023, 76, 103308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolkenov, B.; Duarte, T.; Yang, L.; Yang, F.; Roque, B.; Kebreab, E.; Yang, X. Effects of Red Macroalgae Asparagopsis taxiformis Supplementation on the Shelf Life of Fresh Whole Muscle Beef. Transl. Anim. Sci. 2021, 5, txab056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Loiselle, T.L. Extended Metabolism Methods for Increasing and Extracting Metabolites from Algae and Microorganisms. U.S. Patent 12,116,608, 15 October 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, E.S.; Pádua, V.L.; Giani, A.; Rodríguez, M.; Silva, D.F.; Ferreira, A.F.A.; Júnior, I.C.S.; Pereira, M.C.; Rodrigues, J.L. Validation of a Robust LLE-GC-MS Method for Determination of Trihalomethanes in Environmental Samples. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2018, 190, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roque, B.M.; Salwen, J.K.; Kinley, R.; Kebreab, E. Inclusion of Asparagopsis armata in Lactating Dairy Cows’ Diet Reduces Enteric Methane Emission by over 50 Percent. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 234, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefenoni, H.A.; Räisänen, S.E.; Cueva, S.F.; Wasson, D.E.; Lage, C.F.A.; Melgar, A.; Fetter, M.E.; Smith, P.; Hennessy, M.; Vecchiarelli, B.; et al. Effects of the Macroalga Asparagopsis taxiformis and Oregano Leaves on Methane Emission, Rumen Fermentation, and Lactational Performance of Dairy Cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 4157–4173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGurrin, A.; Maguire, J.; Tiwari, B.K.; Garcia-Vaquero, M. Anti-Methanogenic Potential of Seaweeds and Seaweed-Derived Compounds in Ruminant Feed: Current Perspectives, Risks and Future Prospects. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2023, 14, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eason, C.T.; Fennessy, P.F. Methane Reduction, Health and Regulatory Considerations Regarding Asparagopsis and Bromoform for Ruminants. N. Z. J. Agric. Res. 2025, 68, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condie, L.W.; Smallwood, C.L.; Laurie, R.D. Comparative Renal and Hepatotoxicity of Halomethanes: Bromodichloromethane, Bromoform, Chloroform, Dibromochloromethane and Methylene Chloride. Drug Chem. Toxicol. 1983, 6, 563–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero, P.; Belanche, A.; Jiménez, E.; Hueso, R.; Ramos-Morales, E.; Salwen, J.K.; Kebreab, E.; Yáñez-Ruiz, D.R. Rumen Microbial Degradation of Bromoform from Red Seaweed (Asparagopsis taxiformis) and the Impact on Rumen Fermentation and Methanogenic Archaea. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2023, 14, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Posman, K.M.; Iacono, G.; Cartisano, C.M.; Morrison, S.Y.; Emerson, D.; Price, N.N.; Archer, S.D. The Antimethanogenic Efficacy and Fate of Bromoform and Its Transformation Products in Rumen Fluid. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 25171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sena, F.; Henriques, D.; Dentinho, M.T.; Paulos, K.; Francisco, A.; Portugal, A.P.; Oliveira, A.; Ramos, H.; Bexiga, R.; Moradi, S.; et al. Feeding Sunflower Oil Enriched with Bromoform from Asparagopsis taxiformis Impacts Young Bulls’ Growth, Health, Enteric Methane Production and Carbon Footprint. Animal 2025, 19, 101681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costigan, H.; Shalloo, L.; Egan, M.; Kennedy, M.; Dwan, C.; Walsh, S.; Hennessy, D.; Walker, N.; Zihlmann, R.; Lahart, B. The Effect of Twice Daily 3-Nitroxypropanol Supplementation on Enteric Methane Emissions in Grazing Dairy Cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2024, 107, 9197–9208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, N.A.; Parker, D.B.; Todd, R.W.; Leytem, A.B.; Dungan, R.S.; Hales, K.E.; Ivey, S.L.; Jennings, J. Use of New Technologies to Evaluate the Environmental Footprint of Feedlot Systems. Transl. Anim. Sci. 2018, 2, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alemu, A.W.; Vyas, D.; Manafiazar, G.; Basarab, J.A.; Beauchemin, K.A. Enteric Methane Emissions from Low- and High-Residual Feed Intake Beef Heifers Measured Using GreenFeed and Respiration Chamber Techniques. J. Anim. Sci. 2017, 95, 3727–3737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doreau, M.; Arbre, M.; Rochette, Y.; Lascoux, C.; Eugène, M.; Martin, C. Comparison of 3 Methods for Estimating Enteric Methane and Carbon Dioxide Emission in Nonlactating Cows. J. Anim. Sci. 2018, 96, 1559–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study Day | Period | Min Temperature (°C) | Max Temperature (°C) | Avg Temperature (°C) | Min Wind Speed (m/s) | Max Wind Speed (m/s) | Avg Wind Speed (m/s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −28 | Baseline | 9.17 | 26.12 | 17.60 | 0.20 | 2.83 | 0.98 |

| −27 | Baseline | 18.49 | 28.68 | 25.04 | 0.32 | 1.73 | 0.79 |

| −26 | Baseline | 13.31 | 32.97 | 20.63 | 0.19 | 1.71 | 0.60 |

| −25 | Baseline | 10.87 | 21.25 | 13.85 | 0.22 | 1.83 | 0.84 |

| −24 | Baseline | 7.48 | 15.39 | 12.02 | 0.87 | 2.71 | 1.77 |

| −23 | Baseline | 6.65 | 19.70 | 13.42 | 0.12 | 1.80 | 0.98 |

| −22 | Baseline | 4.87 | 19.58 | 13.32 | 0.13 | 1.09 | 0.54 |

| −21 | Baseline | 4.64 | 23.98 | 16.66 | 0.02 | 0.92 | 0.41 |

| −20 | Baseline | 7.19 | 28.32 | 15.26 | 0.15 | 1.10 | 0.49 |

| −19 | Baseline | 10.81 | 28.90 | 21.62 | 0.07 | 1.35 | 0.80 |

| −18 | Baseline | 9.24 | 29.93 | 20.17 | 0.00 | 1.34 | 0.65 |

| −17 | Baseline | 14.89 | 25.46 | 19.72 | 0.14 | 0.87 | 0.46 |

| −16 | Baseline | 11.08 | 28.91 | 22.44 | 0.23 | 1.03 | 0.59 |

| −15 | Baseline | 10.74 | 25.42 | 19.67 | 0.00 | 2.44 | 1.21 |

| −14 | Adaptation | 10.41 | 28.78 | 19.59 | 0.03 | 1.88 | 0.92 |

| −13 | Adaptation | 12.62 | 17.37 | 15.04 | 0.00 | 2.00 | 0.82 |

| −12 | Adaptation | 12.40 | 25.77 | 19.33 | 0.00 | 2.20 | 1.19 |

| −11 | Adaptation | 9.63 | 29.24 | 19.91 | 0.00 | 1.28 | 0.63 |

| −10 | Adaptation | 14.02 | 21.56 | 17.27 | 0.05 | 1.08 | 0.65 |

| −9 | Adaptation | 14.65 | 27.83 | 18.91 | 0.35 | 1.84 | 1.05 |

| −8 | Adaptation | 14.19 | 30.32 | 20.01 | 0.21 | 1.63 | 0.79 |

| −7 | Adaptation | 12.47 | 16.62 | 13.48 | 0.67 | 2.32 | 1.80 |

| −6 | Adaptation | 14.05 | 29.19 | 20.83 | 0.08 | 1.27 | 0.71 |

| −5 | Adaptation | 12.75 | 23.48 | 18.54 | 0.37 | 1.46 | 0.80 |

| −4 | Adaptation | 14.81 | 29.29 | 21.35 | 0.00 | 1.50 | 0.86 |

| −3 | Adaptation | 13.74 | 37.78 | 24.52 | 0.00 | 1.27 | 0.39 |

| −2 | Adaptation | 16.06 | 39.24 | 27.11 | 0.01 | 1.20 | 0.53 |

| −1 | Adaptation | 18.07 | 40.60 | 26.22 | 0.00 | 1.23 | 0.47 |

| 0 | Full dose | 17.87 | 35.63 | 24.28 | 0.19 | 0.69 | 0.36 |

| 1 | Full dose | 17.06 | 29.63 | 23.20 | 0.28 | 2.40 | 1.34 |

| 2 | Full dose | 17.69 | 29.81 | 20.72 | 0.23 | 1.66 | 0.73 |

| 3 | Full dose | 14.73 | 36.32 | 25.26 | 0.00 | 1.13 | 0.46 |

| 4 | Full dose | 15.24 | 27.82 | 21.13 | 0.00 | 0.64 | 0.20 |

| 5 | Full dose | 16.79 | 37.39 | 25.76 | 0.00 | 0.98 | 0.38 |

| 6 | Full dose | 19.00 | 40.03 | 28.10 | 0.04 | 1.08 | 0.45 |

| 7 | Full dose | 17.90 | 41.35 | 27.31 | 0.00 | 0.88 | 0.20 |

| 8 | Full dose | 16.48 | 42.12 | 27.08 | 0.00 | 1.56 | 0.44 |

| 9 | Full dose | 18.47 | 42.26 | 29.03 | 0.00 | 2.08 | 0.47 |

| 10 | Full dose | 18.76 | 36.65 | 28.27 | 0.00 | 1.59 | 0.58 |

| 11 | Full dose | 18.57 | 46.67 | 30.31 | 0.00 | 0.83 | 0.43 |

| 12 | Full dose | 17.73 | 35.98 | 27.62 | 0.15 | 0.83 | 0.39 |

| 13 | Full dose | 24.14 | 37.04 | 31.30 | 0.11 | 1.86 | 0.85 |

| 14 | Full dose | 20.77 | 36.93 | 26.40 | 0.25 | 1.75 | 1.06 |

| 15 | Full dose | 16.24 | 21.82 | 19.69 | 0.27 | 2.28 | 1.47 |

| 16 | Full dose | 15.13 | 25.52 | 19.39 | 0.21 | 1.41 | 0.67 |

| 17 | Full dose | 12.88 | 28.39 | 19.21 | 0.28 | 1.37 | 0.60 |

| 18 | Full dose | 13.99 | 36.62 | 23.13 | 0.00 | 1.40 | 0.68 |

| 19 | Full dose | 13.16 | 40.86 | 22.84 | 0.18 | 2.52 | 0.57 |

| 20 | Full dose | 16.08 | 37.77 | 23.67 | 0.01 | 0.77 | 0.35 |

| 21 | Full dose | 14.94 | 41.29 | 28.41 | 0.23 | 1.93 | 0.66 |

| 22 | Full dose | 13.77 | 38.55 | 24.46 | 0.00 | 1.44 | 0.51 |

| 23 | Full dose | 18.43 | 32.50 | 25.39 | 0.15 | 2.16 | 1.10 |

| 24 | Full dose | 14.26 | 26.94 | 19.43 | 0.19 | 1.47 | 0.59 |

| 25 | Full dose | 14.64 | 33.52 | 22.08 | 0.07 | 1.26 | 0.56 |

| 26 | Full dose | 15.89 | 28.08 | 19.31 | 0.22 | 2.18 | 1.14 |

| 27 | Full dose | 15.43 | 17.63 | 16.24 | 0.18 | 0.98 | 0.56 |

| 28 | Full dose | 14.67 | 30.14 | 19.03 | 0.12 | 1.34 | 0.72 |

| 29 | Full dose | 10.52 | 28.15 | 18.99 | 0.02 | 0.85 | 0.38 |

| 30 | Full dose | 23.37 | 29.85 | 25.94 | 0.55 | 1.04 | 0.85 |

| 31 | Full dose | 17.49 | 33.00 | 28.45 | 0.00 | 1.18 | 0.80 |

| 32 | Full dose | 11.69 | 36.73 | 23.93 | 0.00 | 1.08 | 0.35 |

| 33 | Full dose | 13.95 | 32.65 | 22.41 | 0.15 | 2.32 | 0.81 |

| 34 | Full dose | 12.63 | 32.69 | 21.55 | 0.01 | 1.40 | 0.49 |

| 35 | Full dose | 15.12 | 32.48 | 21.73 | 0.00 | 1.40 | 0.63 |

| 36 | Full dose | 15.36 | 30.25 | 22.79 | 0.00 | 2.24 | 1.04 |

| 37 | Full dose | 16.02 | 22.52 | 18.95 | 0.00 | 1.32 | 0.50 |

| 38 | Full dose | 15.16 | 28.92 | 20.44 | 0.00 | 1.42 | 0.69 |

| 39 | Full dose | 13.64 | 33.30 | 22.28 | 0.00 | 1.61 | 0.52 |

| 40 | Full dose | 14.79 | 37.52 | 24.75 | 0.06 | 1.96 | 0.62 |

| 41 | Full dose | 16.78 | 30.30 | 22.83 | 0.19 | 2.40 | 0.91 |

| 42 | Full dose | 15.24 | 21.69 | 17.56 | 0.06 | 1.66 | 0.71 |

| 43 | Full dose | 13.70 | 26.48 | 19.41 | 0.10 | 1.54 | 0.89 |

| 44 | Full dose | 21.29 | 30.04 | 26.87 | 0.51 | 1.64 | 1.06 |

| 45 | Full dose | 13.47 | 30.01 | 20.17 | 0.03 | 3.15 | 1.56 |

| 46 | Full dose | 11.82 | 31.77 | 20.32 | 0.11 | 1.28 | 0.63 |

| 47 | Full dose | 10.45 | 30.47 | 20.19 | 0.09 | 1.82 | 0.82 |

| 48 | Full dose | 12.57 | 27.08 | 20.29 | 0.49 | 3.22 | 1.55 |

| 49 | Full dose | 10.70 | 13.87 | 12.18 | 1.25 | 2.81 | 2.07 |

| 50 | Removal | 11.14 | 33.23 | 22.41 | 0.28 | 1.48 | 0.88 |

| 51 | Removal | 10.09 | 35.77 | 20.04 | 0.02 | 2.14 | 1.11 |

| 52 | Removal | 11.44 | 34.96 | 21.85 | 0.00 | 1.44 | 0.54 |

| 53 | Removal | 11.66 | 40.34 | 25.05 | 0.00 | 1.38 | 0.49 |

| 54 | Removal | 15.64 | 36.00 | 21.49 | 0.03 | 1.72 | 1.08 |

| 55 | Removal | 16.45 | 38.42 | 27.15 | 0.00 | 1.19 | 0.57 |

| 56 | Removal | 13.26 | 21.65 | 17.26 | 0.07 | 1.45 | 0.65 |

| Period | Outcome | Control | Seaweed-Based Feed Additive | SE | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Methane, g/d | 197.3 | 193.6 | 8.12 | 0.75 |

| Carbon dioxide, g/d | 7449.8 | 7351.3 | 222.15 | 0.76 | |

| Adaptation | Methane, g/d | 195.8 | 175.1 | 8.07 | 0.08 |

| Carbon dioxide, g/d | 7189.9 | 6946.6 | 221.46 | 0.44 | |

| Full dose | Methane, g/d | 203.2 | 53.7 | 7.36 | <0.01 |

| Carbon dioxide, g/d | 6802.7 | 6370.4 | 211.57 | 0.16 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, J.; Loiselle, T.L.; Theurer, M.E. Evaluation of Seaweed-Based Feed Additive on Enteric Methane Emissions of Grazing Heifers. Animals 2025, 15, 3625. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243625

Chen J, Loiselle TL, Theurer ME. Evaluation of Seaweed-Based Feed Additive on Enteric Methane Emissions of Grazing Heifers. Animals. 2025; 15(24):3625. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243625

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Jianwei, Tamara L. Loiselle, and Miles E. Theurer. 2025. "Evaluation of Seaweed-Based Feed Additive on Enteric Methane Emissions of Grazing Heifers" Animals 15, no. 24: 3625. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243625

APA StyleChen, J., Loiselle, T. L., & Theurer, M. E. (2025). Evaluation of Seaweed-Based Feed Additive on Enteric Methane Emissions of Grazing Heifers. Animals, 15(24), 3625. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243625