Assessment of the Awareness and Use of Quality of Life Tools in Small Animal Practices in Germany

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Survey

2.2. Interviews

3. Results

3.1. Survey

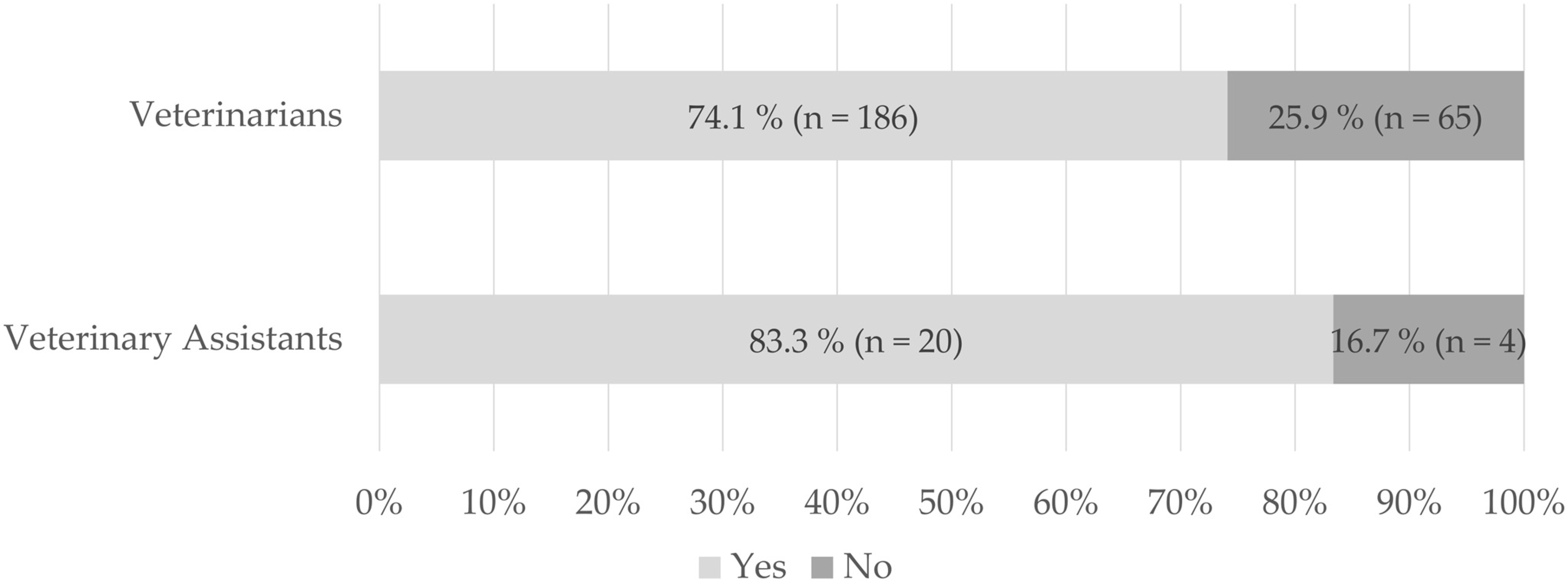

3.1.1. Veterinarians

3.1.2. Veterinarian Assistants

3.2. Interviews

3.2.1. Knowledge of Small Animal Medicine Specialists Regarding Standardized Tools for QoL Assessment

“There are these quality of life scores for atopic dermatitis”

“There is already this FETCH questionnaire, and that is also Quality of Life, I think”

“There are a lot of (incomprehensible mumbling) there are different scores for Cushing’s, there are for diabetes, there are for gastrointestinal, there’s also this [name censored] app, which we helped develop, so for the gastrointestinal tract patients. Sure, I mean there are … all kinds of things”

“We took them into account in the study by [name of PhD student]. There were a few publications, there were some from England and some from the Netherlands, which we have taken into account”

“Yes, of course I’m familiar with questionnaires and, as already mentioned, we also worked on this again ourselves with/so a colleague had already done this as a project”

“I know they exist, I usually teach them too, but I have never used them”

3.2.2. Usage of Standardized Tools for QoL Assessment by Small Animal Medicine Specialists

“I rarely need it, I have to be honest. If I do, it’s only when I’ve been involved in some kind of research; I don’t think I’ve ever used it for everyday use”

“if it’s not as part of a study, it’s often the case that it’s then simply included in a shortened version in the anamnesis, in the questions “how was the animal at home after the therapy?””

“No, for studies actually, but not in everyday practice.”

“Yes, then we have different/Well, you wouldn’t call it a questionnaire/Different scores that are used everywhere, but that’s more of a clinical assessment and not a questionnaire. These are actually the/Oh, and we have a Cushing’s questionnaire/that’s also for a score then, yes”

“So, we have a pain score, we use the Modified Glasgow Pain Scale in everyday practice and pain also has something to do with quality of life, but we don’t have a direct quality of life questionnaire in our practice at the moment”

“With chemo patients, they get a control sheet, so they write it down every day: Food intake, water intake, general condition, diarrhoea, how they’re doing.”

“funnily enough, I actually wanted to establish a score for dogs with inflammatory brain diseases myself and wanted to involve the owners a little and took a few questions from/various validated questions from various other questionnaires. […] and I realized that the questions actually have to be asked differently for each disease, I think. And that’s why I think questionnaires are very, very difficult.”

3.2.3. Arguments for and Against the Use of Standardized Tools for QoL Assessment

“Well-designed questionnaires are super”

“I think there is quite a lot of potential behind it”

“I have nothing against it”

“I hate questionnaires, but simply because I think I’m too stupid to fill them out, so whether it’s any kind of application, anything that involves ticking a box somewhere and filling it in, I’m too stupid for […] but I just don’t like doing it. I also find it awful at the doctor’s when I’m handed one of those things.”

“Yes, I think that makes sense, simply in order to be able to graduate”

“I think you have to do some kind of questionnaire to make studies and things like that more objective”

“You have to do it, otherwise you have nothing that can be objectified”

“from a scientific point of view, it certainly makes sense, you want to have something traceable and documented somehow”

“The question is simply how much time does a veterinarian have to do this […] with vets I always worry that they don’t have time for it”

“I haven’t yet found a really good grading system that is easy to implement without it costing us an infinite amount of time […] I used to do that when I was still at university. I can’t remember why we stopped, I think it was just too time-consuming”

“So, it’s primarily a time factor that plays a role for us rather than anything else”

“A vet never has time, especially not at the moment, so more than five minutes would be too many dropouts, I think, so”

3.2.4. QoL Assessment by Small Animal Medicine Specialists in Their Daily Veterinary Routine

“We take a lot of time in the anamnesis and the owners sit there and we talk and the dogs and cats are allowed to walk. And you can already see a lot there. So, I see how the connection is between them, so dog and cat with the owners, how they behave, how they walk, so this is especially with weight loading, so limbs and stuff, so it is really amazing how much you can see only by observing or especially with cats, how relaxed they walk or not when they are in the consultation. We write that down, so we simply write down what the owners tell us, but also what we observe ourselves.”

“I don’t ask “Has the quality of life improved?”, I ask: “Are you satisfied with the patient’s overall condition?” and then most people start talking”

“So, for me in a practice, “Mrs. Müller, how is he doing?” is absolutely enough. I almost always get an answer that I can do something with. And I might ask three or four more things […] so, of course, I also see things, like can the dog walk, how is he doing, is he in pain, what kind of face is he making?”

“We are very scientific in what we note. It’s just a degree of lameness and a degree of fullness and pain. And this other/quality of life is so flexible, we don’t write it down.”

“We do a lot of allergy sufferers and of course they itch and with that we are dependent on the owner’s assessment and we always have a visual analogue scale that we at least imagine and say “Give a score between zero and ten” […] of course, I know there is this global assessment and this quality of life/attempt to objectify that, we don’t normally do that.”

“So, we have a pain score, we use the Modified Glasgow Pain Scale in everyday life and after all, pain also has something to do with quality of life”

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| QoL | Quality of life |

| PROM | Patient reported outcome measure |

References

- Yeates, J.; Main, D. Assessment of companion animal quality of life in veterinary practice and research. J. Small Anim. Pract. 2009, 50, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belshaw, Z.; Asher, L.; Harvey, N.D.; Dean, R.S. Quality of life assessment in domestic dogs: An evidence-based rapid review. Vet. J. 2015, 206, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doit, H.; Dean, R.S.; Duz, M.; Brennan, M.L. A systematic review of the quality of life assessment tools for cats in the published literature. Vet. J. 2021, 272, 105658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulmer, A.E.; Laven, L.J.; Hill, K.E. Quality of Life Measurement in Dogs and Cats: A Scoping Review of Generic Tools. Animals 2022, 12, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhein, F.F.; Klee, R.; Albrecht, B.; Krämer, S. Instruments to Assess Disease-Specific Quality of Life in Dogs: A Scoping Review. Animals 2025, 15, 1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyatt, G.H. Measuring Health-Related Quality of Life: General Issues. Can. Respir. J. 1997, 4, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeates, J.W.; Mullan, S.; Stone, M.; Main, D.C.J. Promoting discussions and decisions about dogs’ quality-of-life. J. Small Anim. Pract. 2011, 52, 459–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oyama, M.A.; Rush, J.E.; O’Sullivan, M.L.; Williams, R.M.; Rozanski, E.A.; Petrie, J.-P.; Sleeper, M.M.; Brown, D.C. Perceptions and priorities of owners of dogs with heart disease regarding quality versus quantity of life for their pets. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2008, 233, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwacalimba, K.K.; Contadini, F.M.; Spofford, N.; Lopez, K.; Hunt, A.; Wright, A.; Lund, E.M.; Minicucci, L. Owner and Veterinarian Perceptions About Use of a Canine Quality of Life Survey in Primary Care Settings. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, H.; Blackwell, E.; Roberts, C.; Roe, E.; Mullan, S. Broadening the Veterinary Consultation: Dog Owners Want to Talk about More than Physical Health. Animals 2023, 13, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, C.; Blackwell, E.J.; Roe, E.; Murrell, J.C.; Mullan, S. Awareness and Use of Canine Quality of Life Assessment Tools in UK Veterinary Practice. Animals 2023, 13, 1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartorius, N.; Kuyken, W. Translation of Health Status Instruments. In Quality of Life Assessment: International Perspectives; Orley, J., Kuyken, W., Eds.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1994; pp. 3–18. ISBN 978-3-642-79125-3. [Google Scholar]

- Belshaw, Z.; Robinson, N.J.; Dean, R.S.; Brennan, M.L. “I Always Feel Like I Have to Rush…” Pet Owner and Small Animal Veterinary Surgeons’ Reflections on Time during Preventative Healthcare Consultations in the United Kingdom. Vet. Sci. 2018, 5, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoonenboom, J.; Johnson, R.B. How to Construct a Mixed Methods Research Design. Kölner Z. Soziol. 2017, 69, 107–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francis, J.J.; Johnston, M.; Robertson, C.; Glidewell, L.; Entwistle, V.; Eccles, M.P.; Grimshaw, J.M. What is an adequate sample size? Operationalising data saturation for theory-based interview studies. Psychol. Health 2010, 25, 1229–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guest, G.; Bunce, A.; Johnson, L. How Many Interviews Are Enough? Field Methods 2006, 18, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malterud, K.; Siersma, V.D.; Guassora, A.D. Sample Size in Qualitative Interview Studies: Guided by Information Power. Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 1753–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moser, A.; Korstjens, I. Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 3: Sampling, data collection and analysis. Eur. J. Gen. Pract. 2018, 24, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuckartz, U.; Rädiker, S. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Methoden, Praxis, Computerunterstützung: Grundlagentexte Methoden, 5th ed.; Beltz Juventa: Weinheim, Germany; Basel, Switzerland, 2022; ISBN 9783779962311. [Google Scholar]

- Paulhus, D. Social desirable responding: The evolution of a construct. In The Role of Constructs in Psychological and Educational Measurement; Braun, H.I., Jackson, D.N., Wiley, D.E., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2002; pp. 49–69. [Google Scholar]

- Cella, D.; Nolla, K.; Peipert, J.D. The challenge of using patient reported outcome measures in clinical practice: How do we get there? J. Patient Rep. Outcomes 2024, 8, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, J.; Dalkin, S.; Gooding, K.; Gibbons, E.; Wright, J.; Meads, D.; Black, N.; Valderas, J.M.; Pawson, R. Functionality and feedback: A realist synthesis of the collation, interpretation and utilisation of patient-reported outcome measures data to improve patient care. Health Serv. Deliv. Res. 2017, 5, 1–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thestrup Hansen, S.; Kjerholt, M.; Friis Christensen, S.; Hølge-Hazelton, B.; Brodersen, J. Haematologists’ experiences implementing patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) in an outpatient clinic: A qualitative study for applied practice. J. Patient Rep. Outcomes 2019, 3, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipma, W.S.; Jong, M.F.C.D.; Meuleman, Y.; Hemmelder, M.H.; Ahaus, K.C.T.B. Facing the challenges of PROM implementation in Dutch dialysis care: Patients’ and professionals’ perspectives. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0285822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalobos, A.E. Quality-of-life assessment techniques for veterinarians. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Small Anim. Pract. 2011, 41, 519–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, A.; Pollock, K.; Wilson, E.; Burford, J.; England, G.; Freeman, S. Scoping review of end-of-life decision-making models used in dogs, cats and equids. Vet. Rec. 2022, 191, e1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimm, H.; Bergadano, A.; Musk, G.C.; Otto, K.; Taylor, P.M.; Duncan, J.C. Drawing the line in clinical treatment of companion animals: Recommendations from an ethics working party. Vet. Rec. 2018, 182, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehnus, K.S.; Fordyce, P.S.; McMillan, M.W. Ethical dilemmas in clinical practice: A perspective on the results of an electronic survey of veterinary anaesthetists. Vet. Anaesth. Analg. 2019, 46, 260–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyatt, G.H.; Jaeschke, R. Measurements in Clinical Trials: Choosing the Appropriate Approach. In Quality of Life Assessments in Clinical Trials; Spilker, B., Ed.; Raven Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990; pp. 37–46. ISBN 0-88167-590-3. [Google Scholar]

- Kirshner, B.; Guyatt, G. A methodological framework for assessing health indices. J. Chronic Dis. 1985, 38, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohl, R.; Botscharow, J.; Böckelmann, I.; Thielmann, B. Stress and strain among veterinarians: A scoping review. Ir. Vet. J. 2022, 75, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, M.; Hagen, B.N.M.; Gohar, B.; Wichtel, J.; Jones, A.Q. Don’t ignore the tough questions: A qualitative investigation into occupational stressors impacting veterinarians’ mental health. Can. Vet. J. 2025, 66, 274–287. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McMillan, F.D. Quality of life in animals. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2000, 216, 1904–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The WHOQOL Group. The World Health Organization quality of life assessment (WHOQOL): Position paper from the World Health Organization. Soc. Sci. Med. 1995, 41, 1403–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullan, S. Assessment of quality of life in veterinary practice: Developing tools for companion animal carers and veterinarians. Vet. Med. 2015, 6, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morton, D.B. A hypothetical strategy for the objective evaluation of animal well-being and quality of life using a dog model. Anim. Welf. 2007, 16, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunnarsson, S. The conceptualisation of health and disease in veterinary medicine. Acta Vet. Scand. 2006, 48, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, H.; Berzell, M. Reference values and the problem of health as normality: A veterinary attempt in the light of a one health approach. Infect. Ecol. Epidemiol. 2014, 4, 24270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martyushev-Poklad, A.; Yankevich, D.; Petrova, M. Improving the Effectiveness of Healthcare: Diagnosis-Centered Care Vs. Person-Centered Health Promotion, a Long Forgotten New Model. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 819096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paula Vieira, A.D.; Anthony, R. Recalibrating Veterinary Medicine through Animal Welfare Science and Ethics for the 2020s. Animals 2020, 10, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Area of Specialty | Number of Specialists Interviewed | Case Number |

|---|---|---|

| Orthopaedics | 4 | 6, 13, 14, 15 |

| Oncology | 3 | 5, 7, 11 |

| Neurology | 3 | 2, 8, 12 |

| Internal Medicine | 3 | 1, 3, 10 |

| Cardiology | 2 | 4, 9 |

| Dermatology | 1 | 16 |

| Main Category | Category Definition |

|---|---|

| Knowledge about/awareness of QoL assessment tools | All statements that contain specific or vague knowledge or awareness about questionnaires for assessing quality of life and statements that contain a corresponding lack of knowledge. |

| Use of QoL assessment tools | All statements on the use and non-use of questionnaires to assess quality of life. |

| Attitude towards questionnaire-based QoL assessment tools | All statements on the use of questionnaires in general or on personal attitudes toward the use of questionnaires. |

| Own practice of assessing QoL of their patients | All statements regarding the assessment and/or documentation of a patient’s quality of life in one’s own veterinary practice and statements regarding the absence of such assessment and/or documentation. |

| Veterinarians | Veterinary Assistants | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 90% (n = 226) | 100% (n = 24) |

| Male | 10% (n = 25) | - |

| Age | ||

| 18–30 years | 10% (n = 25) | 54.2% (n = 13) |

| 31–60 years | 78.9% (n = 198) | 41.7% (n = 10) |

| >60 years | 11.2% (n = 28) | 4.2% (n = 1) |

| Experience in small animal medicine | ||

| <5 years | 22.3% (n =56) | 41.7% (n = 10) |

| 5–10 years | 19.9% (n = 50) | 25.0% (n = 6) |

| 11–20 years | 23.9% (n = 60) | 29.2% (n = 7) |

| >20 years | 33.9% (n = 85) | 4.2% (n = 1) |

| University | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Freie Universität Berlin | 40 | 15.9 |

| Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin * | 3 | 1.2 |

| University of Veterinary Medicine Hannover | 68 | 27.1 |

| Justus Liebig University Giessen | 73 | 29.1 |

| Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich | 32 | 12.7 |

| Leipzig University | 25 | 10.0 |

| Degree obtained abroad | 10 | 4.0 |

| Total | 251 | 100.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rhein, F.F.; Klee, R.; Albrecht, B.; Krämer, S. Assessment of the Awareness and Use of Quality of Life Tools in Small Animal Practices in Germany. Animals 2025, 15, 3617. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243617

Rhein FF, Klee R, Albrecht B, Krämer S. Assessment of the Awareness and Use of Quality of Life Tools in Small Animal Practices in Germany. Animals. 2025; 15(24):3617. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243617

Chicago/Turabian StyleRhein, Friederike Felicitas, Rebecca Klee, Balazs Albrecht, and Stephanie Krämer. 2025. "Assessment of the Awareness and Use of Quality of Life Tools in Small Animal Practices in Germany" Animals 15, no. 24: 3617. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243617

APA StyleRhein, F. F., Klee, R., Albrecht, B., & Krämer, S. (2025). Assessment of the Awareness and Use of Quality of Life Tools in Small Animal Practices in Germany. Animals, 15(24), 3617. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243617