Comparative Analysis of Meat Quality in Minxinan Black Rabbit and Hyla Rabbit Using Integrated Transcriptomics and Proteomics

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Sample Collection

2.2. Transcriptional Extraction and Data Processing

2.3. Total Protein Extraction and Data Processing

2.4. Combined Analysis of Transcriptome and Proteome

2.5. Construction of Protein Interaction Network

2.6. Determination of Meat Quality

2.6.1. Meat Color

2.6.2. Nutritional Components

2.6.3. Fatty Acid Composition and Content

2.6.4. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

2.6.5. Myoglobin Content

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Transcriptome, Proteome, and Two-Omics Combined Expression Regulation Analysis of MBR and CIR Meat

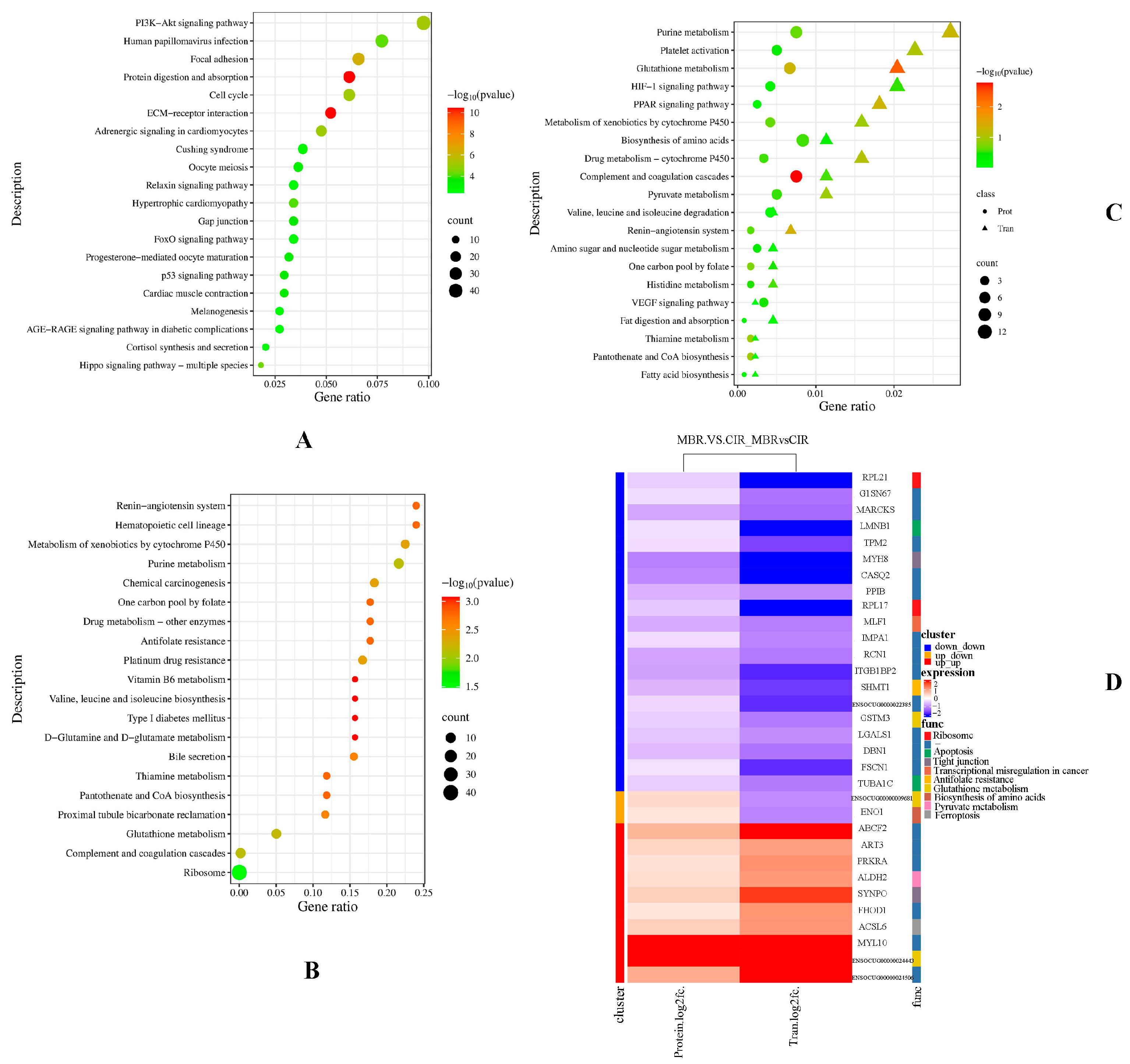

3.2. KEGG Functional Enrichment Analysis

3.3. GO Functional Enrichment Analysis

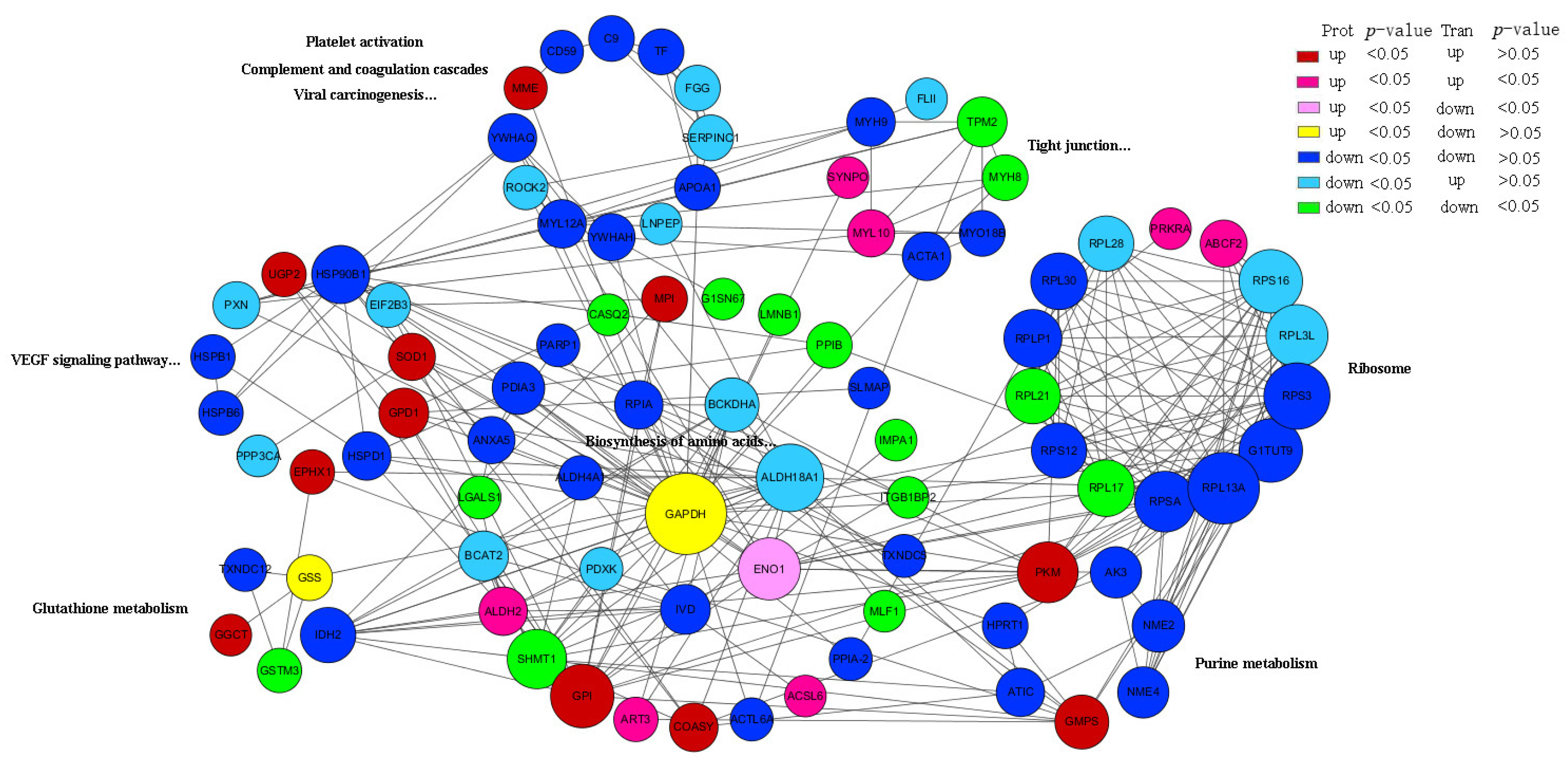

3.4. Protein Regulatory Network Related to Meat Quality and Oxidative Stability in MBR and CIR

3.5. Meat Quality Indicators

4. Discussion

4.1. Antioxidant Capacity

4.2. Meat Color

4.3. Meat Flavor

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MBR | Minxinan black rabbit |

| CIR | Hyla rabbit |

| DEGs | differentially expressed genes |

| DEPs | differentially expressed proteins |

| DAMs | differentially accumulated metabolites |

| SOD1 | superoxide dismutase 1 |

| GGCT | gamma (γ)-glutamylcyclotranserase |

| LTL | longissimus thoracis et lumborum |

| FAME | fatty acid methyl ester |

| GC–MS | Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry |

| TMT | Tandem Mass Tag |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| PPI | protein–protein interaction |

| SFAs | saturated fatty acids |

| UFAs | unsaturated fatty acids |

| MUFAs | monounsaturated fatty acids |

| PUFAs | polyunsaturated fatty acids |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

References

- Pavan, K.; Sharma, N.; Narnoliya, L.K.; Verma, A.K.; Umaraw, P.; Mehta, N.; Ismail-Fitry, M.R.; Kaka, U.; Yong-Meng, G.; Lee, S.-J.; et al. Improving quality and consumer acceptance of rabbit meat: Prospects and challenges. Meat Sci. 2025, 219, 109660. [Google Scholar]

- Szendrő, K.; Szabó-Szentgróti, E.; Szigeti, O. Consumers’ Attitude to Consumption of Rabbit Meat in Eight Countries Depending on the Production Method and Its Purchase Form. Foods 2020, 9, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAOSTAT. Crops and Livestock Products. 2023. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Liu, C.M.; Wang, S.H.; Dong, X.G.; Zhao, J.P.; Ye, X.Y.; Gong, R.G.; Ren, Z.J. Exploring the genomic resources and analysing the genetic diversity and population structure of Chinese indigenous rabbit breeds by RAD-seq. BMC Genom. 2021, 22, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, B.B.; Yang, L.P.; Zhang, Y.J.; Yan, X.F.; Sun, H.T.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Bai, L.Y.; Zhang, H.H. Comparative analysis of meat quality of laiwu black, minxinan black and hyla rabbits. Arch. Anim. Breed. 2024, 67, 503–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notice on the Publication of the National Catalogue of Livestock and Poultry Genetic Resources (2021 Edition). Available online: https://www.moa.gov.cn/govpublic/nybzzj1/202101/t20210114_6359937.htm (accessed on 23 June 2024).

- Chen, D.J.; Sun, S.K.; Chen, Y.F.; Wang, J.X.; Sang, L.; Gao, C.F.; Xie, X.P. Effects of feeding methods on growth and slaughter performance, blood biochemical indices, and intestinal morphology in Minxinan black rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus). Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2023, 55, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, J.Q.; Qin, L.W.; Zhang, F.; Fan, X.Y.; Jin, H.Y.; Du, Z.J.; Guo, Y.K.; Liu, W.W.; Liu, Q.H. Effects of JUNCAO Ganoderma lucidum polysaccharide peptide on slaughter performance and intestinal health of Minxinan black rabbits. Anim. Biotechnol. 2024, 35, 2259436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, L.; Wang, J.X.; Sun, S.K.; Chen, D.J.; Chen, Y.F.; Xie, X.P.; Zheng, B.L. Carcass Characteristics and Meat Quality of Local Breeds and New Zealand White Rabbits. Fujian J. Agric. Sci. 2018, 33, 888–892. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G.Y.; Li, M.Y.; Liu, M.; Sun, H.T.; Bai, L.Y.; Liu, C.; Yang, L.P.; Jiang, W.X.; Wang, P.; Gao, S.X. Effects of different slaughter ages on slaughter performance, fat deposition and muscle quality of Minxinan black rabbits. Chin. J. Anim. Sci. 2022, 58, 224–228. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G.Y.; Bai, L.Y.; Sun, H.T.; Liu, C.; Yang, L.P.; Jiang, W.X.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, S.X. The effect of conjugated linoleic acids on the growth performance, carcase composition and meat quality of fattening rabbits. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2022, 21, 1074–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.Y.; Sun, H.T.; Liu, C.; Bai, L.Y.; Yang, L.P.; Jiang, W.X.; Gao, S.X. Impact of different dietary fibre sources on production performance, bacterial composition and metabolites in the caecal contents of rabbits. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2023, 107, 1279–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, M.; Rubin, C.-J.; Di Palma, F.; Albert, F.W.; Alföldi, J.; Martinez, B.A.; Pielberg, G.; Rafati, N.; Sayyab, S.; Turner-Maier, J.; et al. Rabbit genome analysis reveals a polygenic basis for phenotypic change during domestication. Science 2014, 345, 1074–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Su, Y.; Elzo, M.A.; Jia, X.; Chen, S.; Lai, S. Comparison of carcass and meat quality traits among three rabbit breeds. Korean J. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2016, 36, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, D.; Ding, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhao, H. Integration analysis of hair follicle transcriptome and proteome reveals the mechanisms regulating wool fiber diameter in angora rabbits. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuang, L.; Zeng, J.; Li, Y.; Zheng, J.; Ren, Y.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, C.; Yang, C.; Mei, X.; et al. Delineating molecular regulatory network of meat quality of longissimus dorsi indicated by transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomics analysis in rabbit. J. Proteom. 2024, 300, 105179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. HISAT: A fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, P.; Markiel, A.; Ozier, O.; Baliga, N.S.; Wang, J.T.; Ramage, D.; Amin, N.; Schwikowski, B.; Ideker, T. Cytoscape: A software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003, 13, 2498–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 5009.3-2016; National Food Safety Standard-Determination of Moisture in Foods. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2016.

- GB 5009.5-2016; National Food Safety Standard-Determination of Protein in Foods. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2016.

- GB 5009.6-2016; National Food Safety Standard-Determination of Fat in Foods. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2016.

- GB 5009.124-2016; National Food Safety Standard-Determination of Amino Acids in Foods. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2016.

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsburn, B.C. Proteome discoverer—A community enhanced data processing suite for protein informatics. Proteomes 2021, 9, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Wang, L.G.; Han, Y.; He, Q.Y. clusterProfiler: An R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS 2012, 16, 284–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; He, Z.Q.; Zhang, X.Y.; Chen, Y.J.; Zuo, J.J.; Cao, Y. Proteome and Transcriptome Analysis of the Antioxidant Mechanism in Chicken Regulated by Eucalyptus Leaf Polyphenols Extract. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2020, 1384907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, Y.A.; Cha, M.J.; Park, S.; Lee, S.; Lim, Y.J.; Son, D.W.; Lee, E.J.; Kim, P.; Chang, S. Development of a normal porcine cell line growing in a heme-supplemented, serum-free condition for cultured meat. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, Y.H.; Zheng, C.B.; Zheng, J.; Ma, L.; Ma, X.R.; Zhong, Y.Z.; Zhao, X.C.; Li, F.N.; Guo, Q.P.; Yin, Y.L. Profiles of muscular amino acids, fatty acids, and metabolites in shaziling pigs of different ages and relation to meat quality. Sci. China Life Sci. 2023, 66, 1323–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Li, D.; Tu, J.C.; Zhong, Y.J.; Zhang, D.; Wang, Z.M.; Tao, X.Q. Mechanisms of change in gel water-holding capacity of myofibrillar proteins affected by lipid oxidation: The role of protein unfolding and cross-linking. Food Chem. 2021, 344, 128587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L.L.; Shi, Z.Y.; Ou, X.Q.; Wu, D.; Zhang, X.M.; Hu, H.; Yuan, J.; Wang, W.; et al. RNA-Seq reveals differentially expressed genes affecting polyunsaturated fatty acids percentage in the Huangshan Black chicken population. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0195132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Gordon, L.J. The Peroxiredoxin Family: An Unfolding Story. Subcell. Biochem. 2017, 83, 127–147. [Google Scholar]

- Atiya, A.; Muhsinah, A.B.; Alrouji, M.; Alhumaydhi, F.A.; Abdulmonem, W.A.; Aljasir, M.A.; Sharaf, S.E.; Furkan, M.; Khan, R.H.; Shahwan, M.; et al. Unveiling promising inhibitors of superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) for therapeutic interventions. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 253, 126684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takumi, O.; Kunisato, K.; Taiyu, W.; Nobuhiro, F.; Takakazu, N. Enhancement of oxidative reaction by the intramolecular electron transfer between the coordinated redox-active metal ions in SOD1. J. Phys. Chem. B 2020, 124, 2116–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Qiu, S.; Shi, J.Y.; Wang, S.S.; Wang, M.F.; Xu, Y.L.; Nie, Z.F.; Liu, C.R.; Liu, C.L. A new function of copper zinc superoxide dismutase: As a regulatory DNA-binding protein in gene expression in response to intracellular hydrogen peroxide. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, 5074–5085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montllor-Albalate, C.; Colin, A.E.; Chandrasekharan, B.; Bolaji, N.; Andersen, J.L.; Wayne, O.F.; Reddi, A.R. Extra-mitochondrial cu/zn superoxide dismutase (Sod1) is dispensable for protection against oxidative stress but mediates peroxide signaling in saccharomyces cerevisiae. Redox Biol. 2019, 21, 101064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.L.; Tian, X.Y.; Liu, T.L.; Li, M.X.; Wang, W.G.; Wang, P.; Guo, Z.L. Hydroxytyrosol Alleviated Hypoxia-Mediated PC12 Cell Damage through Activating PI3K/AKT/mTOR-HIF-1α Signaling. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 8673728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Vivancos, P.; Simone, A.D.; Kiddle, G.; Foyer, C.H. Glutathione–linking cell proliferation to oxidative stress. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015, 89, 1154–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Wang, Q.; Guan, J.; Gong, S.; Chai, T.; Wang, J.; Qiao, K. DsGGCT2-1 involved in the detoxification of cd and pb through the glutathione catabolism in dianthus spiculifolius. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 225, 109976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Z.; Sun, X.; Wang, S.; Bai, D.; Zhao, X.; Han, Y.; Hao, P.; Liu, X.S. Ggct (γ-glutamyl cyclotransferase) plays an important role in erythrocyte antioxidant defense and red blood cell survival. Br. J. Haematol. 2021, 195, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.Z.; Gao, Q.G.; Xu, L.; Pang, S.; Liu, Z.Q.; Wang, C.J.; Tan, W.M. Characterization of glutathione S-transferases in the detoxification of metolachlor in two maize cultivars of differing herbicide tolerance. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2017, 143, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, J.D.; Flanagan, J.U.; Jowsey, I.R. Glutathione transferases. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2005, 45, 51–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allocati, N.; Masulli, M.; Ilio, C.D.; Federici, L. Glutathione transferases: Substrates, inihibitors and pro-drugs in cancer and neurodegenerative diseases. Oncogenesis 2018, 7, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.G.; Wang, P.; Pi, R.B.; Gao, J.; Fu, J.J.; Fang, J.; Qin, J.; Zhang, H.J.; Li, R.F.; Chen, S.R.; et al. Reduced expression of GSTM2 and increased oxidative stress in spontaneously hypertensive rat. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2008, 309, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Tchaikovskaya, T.; Tu, Y.S.; Chapman, J.; Qian, B.; Ching, W.M.; Tien, M.; Rowe, J.D.; Patskovsky, Y.V.; Listowsky, I.; et al. Rat glutathione S-transferase M4-4: An isoenzyme with unique structural features including a redox-reactive cysteine-115 residue that forms mixed disulphides with glutathione. Biochem. J. 2001, 356, 403–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul, S.M.; Patnaik, A. Molecular insights into antioxidant efficiency of melanin: A sustainable antioxidant for natural rubber formulations. J. Phys. Chem. B 2023, 127, 8242–8256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekiz, B.; Yilmaz, A.; Ozcan, M.; Kocak, O. Effect of production system on carcass measurements and meat quality of Kivircik lambs. Meat Sci. 2012, 90, 465–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.Y.; Sun, H.T.; Yang, L.P.; Bai, L.Y.; Jiang, W.X.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Z.K.; Gao, S.X. Comparative Analysis on Slaughter Performance and Muscle Quality of Minxinan Black Rabbit and Commercial Iraq Rabbit. Acta Ecol. Anim. Domest. 2022, 43, 41–46. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zi, X.; Ge, X.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Sun, D.; Li, Z.; Liu, M.; You, Z.; Wang, B.; Kang, J.; et al. Transcriptome profile analysis identifies candidate genes for the melanin pigmentation of skin in tengchong snow chickens. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, W.H.; Han, M.L.; Bu, Y.; Li, X.P.; Yi, S.M.; Xu, Y.X.; Li, J.R. Plant polyphenols regulating myoglobin oxidation and color stability in red meat and certain fish: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 2276–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picard, B.; Gagaoua, M. Muscle fiber properties in cattle and their relationships with meat qualities: An overview. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 6021–6039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Sun, H.T.; Bai, L.Y.; Yang, L.P.; Jiang, W.X.; Wang, W.Z.; Liu, G.Y.; Gao, S.X. A Comparative Study on Slaughter Performance and Meat Quality of Min Southwest Black and New Zealand White Rabbits. Chin. J. Anim. Sci. 2021, 57, 75–80. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chumsri, P.; Panpipat, W.; Cheong, L.; Panya, A.; Phonsatta, N.; Chaijan, M. Biopreservation of refrigerated mackerel (Auxis thazard) slices by rice starch-based coating containing polyphenol extract from glochidion wallichianum leaf. Foods 2022, 11, 3441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.Y.; Tonissen, K.F.; Trapani, G.D. Modulating skin colour: Role of the thioredoxin and glutathione systems in regulating melanogenesis. Biosci. Rep. 2021, 41, BSR20210427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galván, I.; Jorge, A.; García-Gil, M. Pheomelanin molecular vibration is associated with mitochondrial ROS production in melanocytes and systemic oxidative stress and damage. Integr. Biol. 2017, 9, 751–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Guo, L.; Ding, X.; Li, F.; Xu, H.; Li, S.; Wang, X.; Li, K.; Yue, X. Supplementation of chestnut tannins in diets can improve meat quality and antioxidative capability in hu lambs. Meat Sci. 2023, 206, 109342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.; Wang, Y.; Yang, W.T.; Li, Z.; Zhang, X.J.; Zhou, L.; Gui, J.F. Upregulation of the PPAR signaling pathway and accumulation of lipids are related to the morphological and structural transformation of the dragon-eye goldfish eye. Sci. China Life Sci. 2021, 64, 1031–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Liu, T.; Peng, P.; Fu, Y.; Shi, S.; Liang, S.; Chen, X.; Wang, K.; Zhou, R. Integrated transcriptomic analysis of liver and muscle tissues reveals candidate genes and pathways regulating intramuscular fat deposition in beef cattle. Animals 2025, 15, 1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.F.; Choi, S.H.; Li, Q.; Wang, Y.; Sun, B.; Tang, L.; Wang, E.Z.; Hua, H.; Li, X.Z. Overexpression of DGAT2 stimulates lipid droplet formation and triacylglycerol accumulation in bovine satellite cells. Animals 2022, 12, 1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, Y.H.; Bu, S.Y. Suppression of long chain acyl-CoA synthetase blocks intracellular fatty acid flux and glucose uptake in skeletal myotubes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2020, 1865, 158678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, F.; Li, Q.; Sun, G.; Wei, F.; Wu, Z.; Meng, Y.; Ma, R. A miRNA-mRNA study reveals the reason for quality heterogeneity caused by marbling in triploid rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) fillets. Food Biosci. 2025, 68, 106421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Yue, Y.J.; Li, J.Y.; Liu, J.B.; Yuan, C.; Guo, T.T.; Zhang, D.; Yang, B.H.; Lu, Z.K. Transcriptome-metabolome analysis reveals how sires affect meat quality in hybrid sheep populations. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 967985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, M.S. Reducing the fat content in ground beef without sacrificing quality: A review. Meat Sci. 2012, 91, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassam, S.M.; Noleto-Dias, C.; Farag, M.A. Dissecting grilled red and white meat flavor: Its characteristics, production mechanisms, influencing factors and chemical hazards. Food Chem. 2022, 371, 131139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.W.; Yu, S.C.; Guo, J.T.; Wang, J.F.; Mei, C.G.; Abbas, R.S.H.; Cheng, G.; Zan, L.S. Comprehensive analysis of transcriptome and metabolome reveals regulatory mechanism of intramuscular fat content in beef cattle. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 2911–2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.B.; Ma, Q.L.; Li, Y.; Bai, S.; Huang, Y.T.; Cui, W.Y.; Accoroni, C.; Fan, B.; Wang, F.Z. Effects of unsaturated C18 fatty acids on “glucose-glutathione” maillard reaction: Comparison and formation pathways of initial stage and meaty flavor compounds. Food Res. Int. 2025, 201, 115645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.J.; Lee, G.; Yun, S.H.; Lee, W.; Yu, J.; Kim, S.K.; Lee, B.H. The role of SHMT2 in modulating lipid metabolism in hepatocytes via glycine-mediated mTOR activation. Amino Acids 2022, 54, 823–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, T.T.; Duan, M.C.; Chen, L.; Tian, Y.; Xu, W.W.; Zeng, T.; Lu, L.Z. The difference between young and older ducks: Amino acid, free fatty acid, nucleotide compositions and breast muscle proteome. Food Chem. X 2025, 25, 102117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picard, B.; Cougoul, A.; Couvreur, S.; Bonnet, M. Relationships between the abundance of 29 proteins and several meat or carcass quality traits in two bovine muscles revealed by a combination of univariate and multivariate analyses. J. Proteom. 2023, 273, 104792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tansutaphanit, S.; Haga, Y.; Kabeya, N.; Matsushita, Y.; Kondo, H.; Hirono, I.; Satoh, S. Impact of purine nucleotide on fatty acid metabolism and expression of lipid metabolism-related gene in the liver cell of rainbow trout oncorhynchus mykiss. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2023, 266, 110845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Morar, M.; Ealick, S.E. Structural biology of the purine biosynthetic pathway. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2008, 65, 3699–3724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, T.; Wu, W.D.; Tang, X.Y.; Ge, Q.Q.; Zhan, J.L. Screening out important substances for distinguishing Chinese indigenous pork and hybrid pork and identifying different pork muscles by analyzing the fatty acid and nucleotide contents. Food Chem. 2021, 350, 129219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iuso, D.; Garcia-Saez, I.; Couté, Y.; Yamaryo-Botté, Y.; Erba, E.B.; Adrait, A.; Zeaiter, N.; Tokarska-Schlattner, M.; Jilkova, Z.M.; Boussouar, F.; et al. Nucleoside diphosphate kinases 1 and 2 regulate a protective liver response to a high-fat diet. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadh0140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.F.; Yuan, L.; Sui, Y.; Feng, S.; Li, H.L.; Li, X. NME4 mediates metabolic reprogramming and promotes nonalcoholic fatty liver disease progression. EMBO Rep. 2024, 25, 378–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Fu, L.; Liu, C.; He, L.; Liu, H.; Han, D.; Zhu, X.; Yang, Y.; Jin, J.; Xie, S. Dietary ribose supplementation improves flesh quality through purine metabolism in gibel carp (Carassius auratus gibelio). Anim. Nutr. 2023, 13, 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mi, W.; Sang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, G.; Yang, L.; Sun, H.; Zhang, H.; Fu, G.; Gao, C.; Bai, L. Comparative Analysis of Meat Quality in Minxinan Black Rabbit and Hyla Rabbit Using Integrated Transcriptomics and Proteomics. Animals 2025, 15, 3616. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243616

Mi W, Sang L, Zhang Y, Liu G, Yang L, Sun H, Zhang H, Fu G, Gao C, Bai L. Comparative Analysis of Meat Quality in Minxinan Black Rabbit and Hyla Rabbit Using Integrated Transcriptomics and Proteomics. Animals. 2025; 15(24):3616. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243616

Chicago/Turabian StyleMi, Weiwei, Lei Sang, Yajia Zhang, Gongyan Liu, Liping Yang, Haitao Sun, Haihua Zhang, Guanhua Fu, Chengfang Gao, and Liya Bai. 2025. "Comparative Analysis of Meat Quality in Minxinan Black Rabbit and Hyla Rabbit Using Integrated Transcriptomics and Proteomics" Animals 15, no. 24: 3616. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243616

APA StyleMi, W., Sang, L., Zhang, Y., Liu, G., Yang, L., Sun, H., Zhang, H., Fu, G., Gao, C., & Bai, L. (2025). Comparative Analysis of Meat Quality in Minxinan Black Rabbit and Hyla Rabbit Using Integrated Transcriptomics and Proteomics. Animals, 15(24), 3616. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243616