Effects of a Feed Sanitizer in Sow Diets on Sow and Piglet Performance

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals, Housing, and Treatments

2.2. Sow and Piglet Performance

2.2.1. Sows

2.2.2. Piglets

2.3. Feed Sample Analysis

2.4. Microbiome Sample Collection

2.4.1. Sows

2.4.2. Piglets

2.5. DNA Extraction and Sequencing

2.6. Statistical Analyses

2.6.1. Sow and Piglet Performance

2.6.2. Microbiome Data

3. Results

3.1. Chemical Analysis

3.2. Sow and Piglet Performance

3.3. Microbiome Composition Across Samples

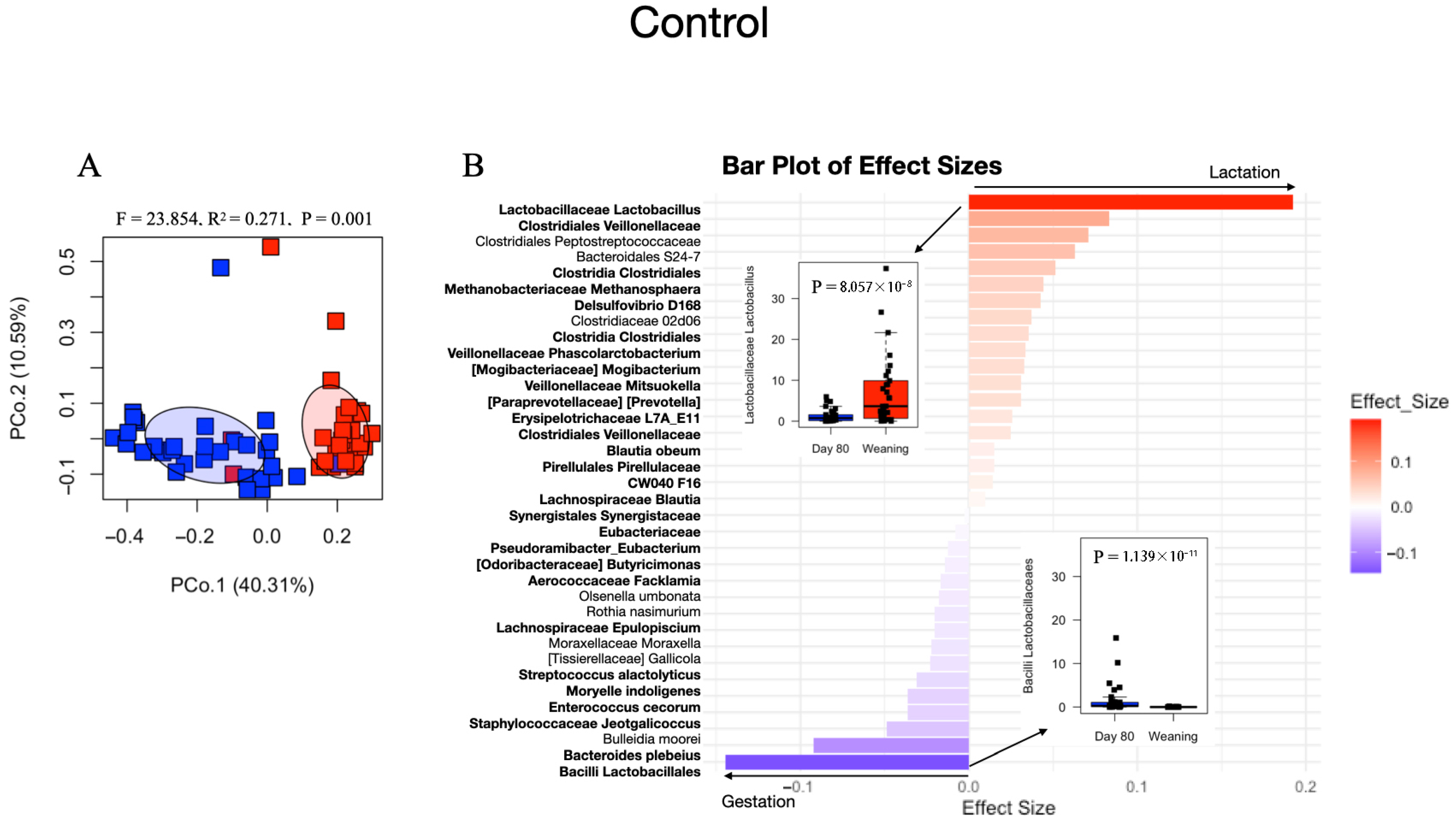

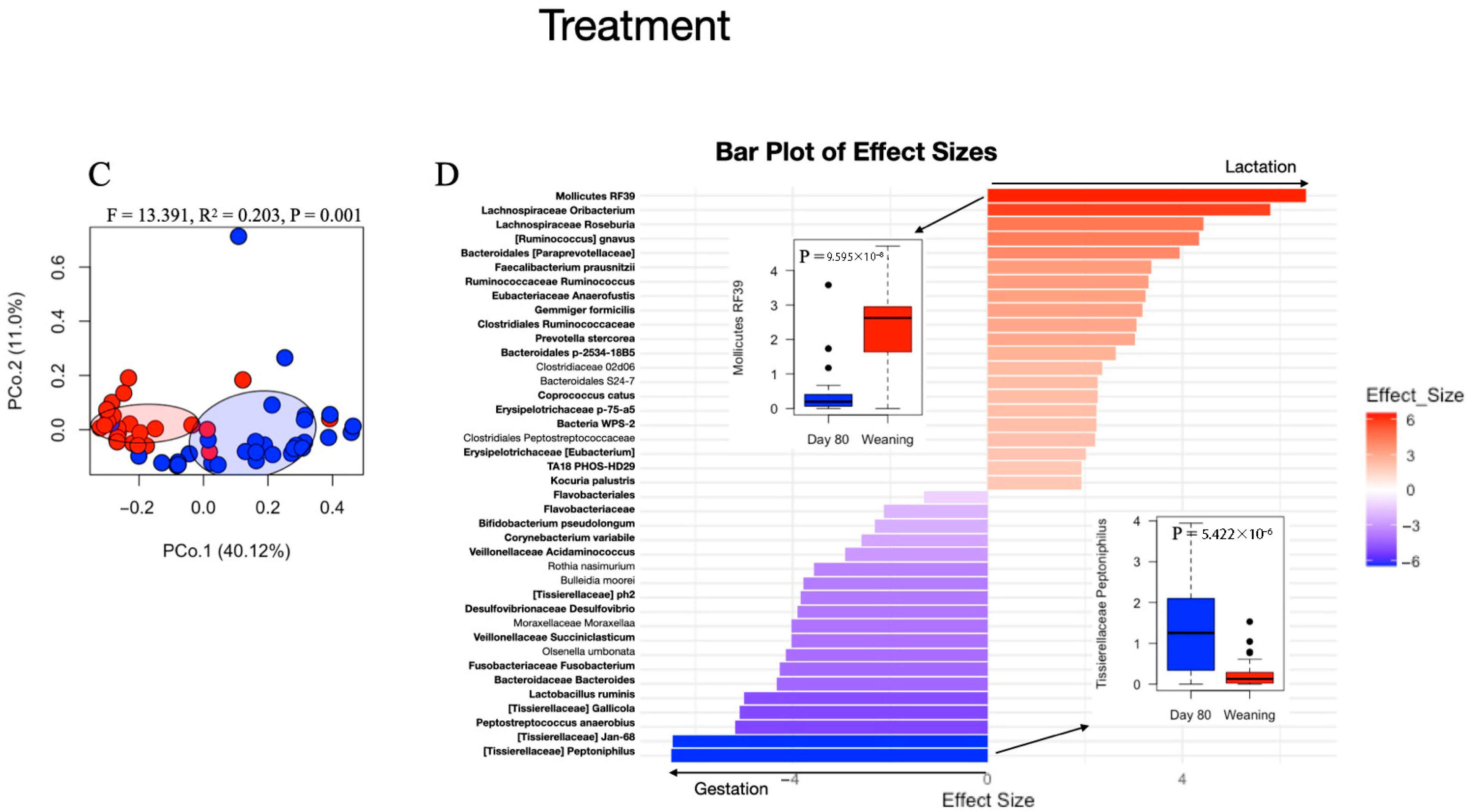

3.4. Effects of Feed Sanitizer on Microbial Composition and Diversity of Sow Fecal Samples

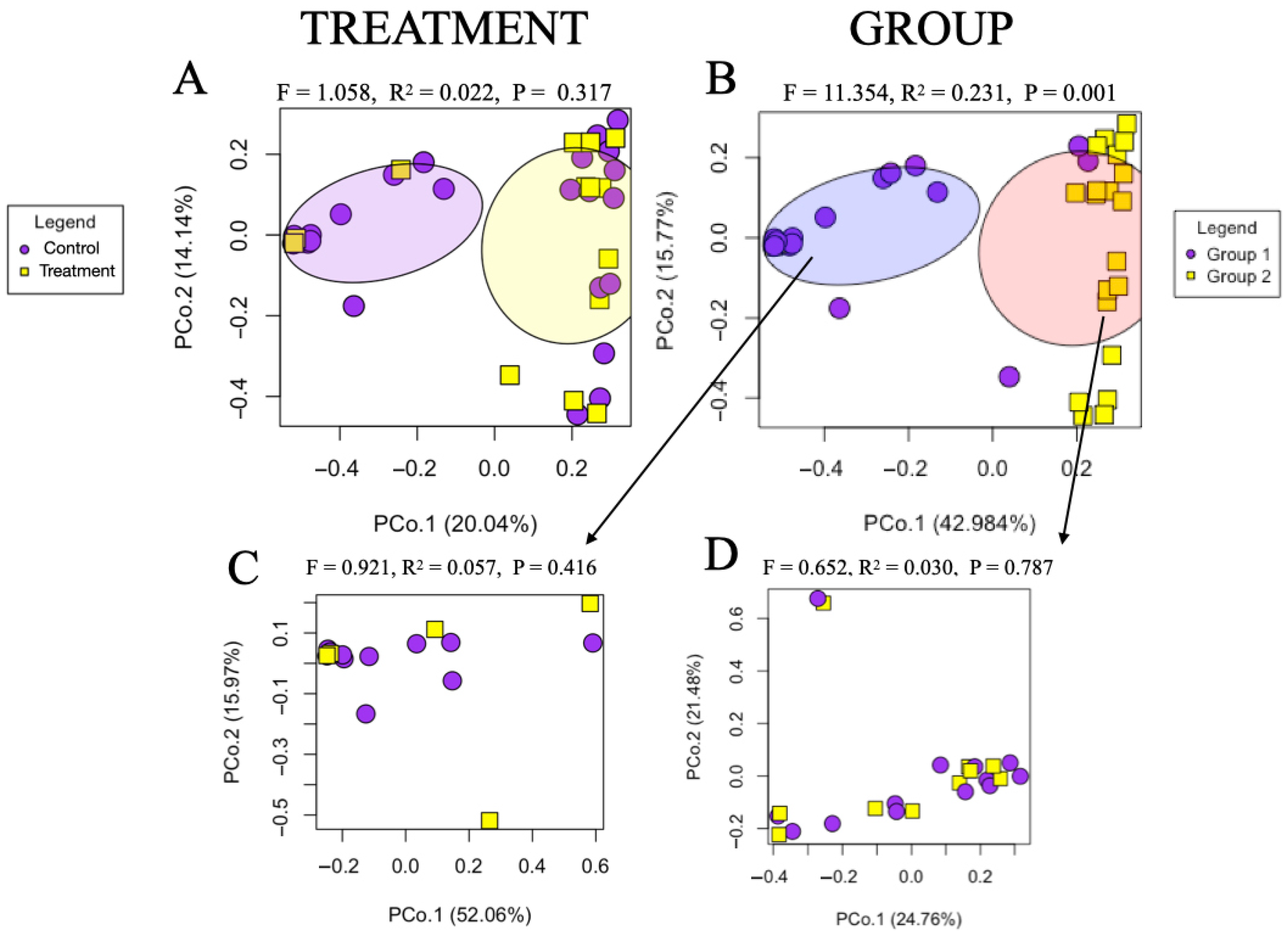

3.5. Effects of Feed Sanitizer on Microbial Composition and Diversity of Piglet Fecal Samples

4. Discussion

4.1. Feed Sanitizer Level

4.2. Feed Sanitizer Has Minor Effects on Sow and Piglet Performance

4.3. Limited Differences in Sow Microbiome Attributed to Feed Sanitizer

4.4. Lack of Differences in Piglet Microbiome Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maciorowski, K.G.; Herrera, P.; Jones, F.T.; Pillai, S.D.; Ricke, S.C. Effects on poultry and livestock of feed contamination with bacteria and fungi. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2007, 133, 109–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomičić, Z.; Čabarkapa, I.; Čolović, R.; Đuragić, O.; Tomičić, R. Salmonella in the feed industry: Problems and potential solutions. J. Agron. 2019, 2, 130–137. [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie, M.A.; Bains, B.S. Dissemination of Salmonella serotypes from raw feed ingredients to chicken carcases. Poul. Sci. 1976, 55, 957–960. [Google Scholar]

- Ricke, S.C.; Richardson, K.; Dittoe, D.K. Formaldehydes in feed and their potential interaction with the poultry gastrointestinal tract microbial community—A review. Front. Vet. Sci. 2019, 6, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, H.K.; Kalaria, R.K.; Kahimani, M.R.; Shah, G.S.; Dholakiya, B.Z. Prevention and control of mycotoxins for food safety and security of human and animal feed. In Fungi Bio-Prospects in Sustainable Agriculture, Environment and Nano-Technology; Sharma, V.K., Shah, M.P., Parmar, S., Kumar, A., Eds.; Elsevier: London, UK, 2021; Volume 3, pp. 315–345. [Google Scholar]

- Karlovsky, P.; Suman, M.; Berthiller, F.; De Meester, J.; Eisenbrand, G.; Perrin, I.; Oswald, I.P.; Speijers, G.; Chiodini, A.; Recker, T.; et al. Impact of food processing and detoxification treatments on mycotoxin contamination. Mycotoxin Res. 2016, 32, 179–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sbardella, M.; Perina, D.D.P.; Andrade, C.D.; Longo, F.A.; Miyada, V.S. Effects of a dietary added formaldehyde-propionic acid blend on feed enterobacteria counts and on growing pig performance and fecal formaldehyde excretion. Cienc. Rural 2014, 45, 474–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avila, L.P.; Sweeney, K.M.; Schaeffer, C.; Holcombe, N.; Selby, C.; Montiel, E.; Wilson, J.L. Broiler breeder feed treatment with a formaldehyde-based sanitizer and its consequences on reproduction, feed and egg contamination, and offspring livability. Appl. Poul. Res. 2023, 32, 100330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, P.J.; Siraki, A.G.; Shangari, N. Aldehyde sources, metabolism, molecular toxicity mechanisms, and possible effects on human health. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2005, 35, 609–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaden, D.A.; Mandin, C.; Nielsen, G.D.; Wolkoff, P. Formaldehyde. In WHO Guidelines for Indoor Air Quality: Selected Pollutants; World Health Organization: Bonn, Germany, 2010; pp. 103–142. [Google Scholar]

- DeRouchey, J.M.; Tokach, M.D.; Nelssen, J.L.; Goodband, R.D.; Dritz, S.S.; Woodworth, J.C.; James, B.W.; Webster, M.J.; Hastad, C.W. Evaluation of methods to reduce bacteria concentrations in spray-dried animal plasma and its effects on nursery pig performance. J. Anim. Sci. 2004, 82, 250–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.M.; Crenshaw, J.D.; Polo, J.; Mellick, D.; Bienhoff, M.; Stein, H.H. Impact of formaldehyde addition to spray-dried plasma on functional parameters and animal performance. Transl. Anim. Sci. 2019, 3, 654–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, H.E.; Cochrane, R.A.; Woodworth, J.C.; DeRouchey, J.M.; Dritz, S.S.; Tokach, M.D.; Jones, C.K.; Fernando, S.C.; Burkey, T.E.; Li, Y.S.; et al. Effects of dietary supplementation of formaldehyde and crystalline amino acids on gut microbial composition of nursery pigs. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 8164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knauer, M.T.; Baitinger, D.J. The Sow Body Condition Caliper. Appl. Eng. Agric. 2015, 31, 175–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gohl, D.M.; Vangay, P.; Garbe, J.; MacLean, A.; Hauge, A.; Becker, A.; Gould, T.J.; Clayton, J.B.; Johnson, T.J.; Hunter, R.; et al. Systematic improvement of amplicon marker gene methods for increased accuracy in microbiome studies. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016, 34, 942–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolyen, E.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.R.; Bokulich, N.A.; Abnet, C.C.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Alexander, H.; Alm, E.J.; Arumugam, M.; Asnicar, F.; et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.A.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, D.; Price, M.N.; Goodrich, J.; Nawrocki, E.P.; DeSantis, T.Z.; Probst, A.; Andersen, G.L.; Knight, R.; Hugenholtz, P. An improved Greengenes taxonomy with explicit ranks for ecological and evolutionary analyses of bacteria and archaea. ISME J. 2012, 6, 610–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langille, M.G.I.; Zaneveld, J.; Caporaso, J.G.; McDonald, D.; Knights, D.; Reyes, J.A.; Clemente, J.C.; Burkepile, D.E.; Vega Thurber, R.L.; Knight, R.; et al. Predictive functional profiling of microbial communities using 16S rRNA marker gene sequences. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013, 31, 814–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksanen, J.; Simpson, G.L.; Blanchet, F.G.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; Minchin, P.R.; O’Hara, R.B.; Solymos, P.; Stevens, M.H.H.; Szoecs, E.; et al. Vegan: Community Ecology Package 2001. Version 2.6-10. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/vegan/vegan.pdf (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Paradis, E.; Blomberg, S.; Bolker, B.; Brown, J.; Claramunt, S.; Claude, J.; Cuong, H.S.; Desper, R.; Didier, G.; Durand, B.; et al. Ape: Analyses of Phylogenetics and Evolution. 2002. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/ape/index.html (accessed on 6 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Mallick, H.; Rahnavard, A.; McIver, L.J.; Ma, S.; Zhang, Y.; Nguyen, L.H.; Tickle, T.L.; Weingart, G.; Ren, B.; Schwager, E.H.; et al. Multivariable association discovery in population-scale meta-omics studies. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2021, 17, e1009442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolde, R. Pheatmap: Pretty Heatmaps 2010, Version 1.0.12. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/pheatmap/pheatmap.pdf (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Gilbert, N.L.; Gauvin, D.; Guay, M.; Héroux, M.-È.; Dupuis, G.; Legris, M.; Chan, C.C.; Dietz, R.N.; Lévesque, B. Housing characteristics and indoor concentrations of nitrogen dioxide and formaldehyde in Quebec City, Canada. Environ. Res. 2006, 102, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salthammer, T.; Fuhrmann, F.; Kaufhold, S.; Meyer, B.; Schwarz, A. Effects of climatic parameters on formaldehyde concentrations in indoor air. Indoor Air 1995, 5, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, N.L.; Guay, M.; Gauvin, D.; Dietz, R.N.; Chan, C.C.; Lévesque, B. Air change rate and concentration of formaldehyde in residential indoor air. Atmos. Environ. 2008, 42, 2424–2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauber, T.E.; Stahly, T.S.; Nonnecke, B.J. Effect of level of chronic immune system activation on the lactational performance of sows. J. Anim. Sci. 1999, 77, 1985–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peaker, M.; Hanwell, A. Comparative Aspects of Lactation. In The Proceedings of a Symposium Held at the Zoological Society of London on 11 and 12 November 1976; Academic Press: London, UK, 1977; Volume 41. [Google Scholar]

- Gittleman, J.L.; Thompson, S.D. Energy allocation in mammalian reproduction. Am. Zool. 1988, 28, 863–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NRC (National Research Council). Nutrient Requirements of Swine, 11th ed.; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; pp. 1–420. [Google Scholar]

- Oftedal, O.T. Use of maternal reserves as a lactation strategy in large mammals. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2000, 59, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svendsen, J.; Wilson, M.R.; Ewert, E. Serum protein levels in pigs from birth to maturity and in young pigs with and without Enteric Colibacillosis. Acta. Vet. Scand. 1972, 13, 528–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soede, N.M.; Langendijk, P.; Kemp, B. Reproductive cycles in pigs. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2011, 124, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentry, J.G.; Johnson, A.K.; McGlone, J.J. The welfare of growing-finishing pigs. In Welfare of Pigs; Faucitano, L., Schaefer, A.L., Eds.; Brill: Berlin, Germany, 2008; pp. 133–159. [Google Scholar]

- Reimert, I.; Rodenburg, T.B.; Ursinus, W.W.; Kemp, B.; Bolhuis, J.E. Selection based on indirect genetic effects for growth, environmental enrichment and coping style affect the immune status of pigs. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e108700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christenson, R.K.; Ford, J.J.; Redmer, D.A. Maturation of ovarian follicles in the prepubertal gilt. J. Reprod. Fert. Suppl. 1985, 33, 21–36. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, L.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, W.; Lan, T.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Liao, X.; Mi, J. The dynamic changes of gut microbiota during the perinatal period in sows. Animals 2020, 10, 2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zheng, J.; He, J.; Liu, H.; Huang, Y.; Huang, L.; Wang, K.; Zhao, X.; Feng, B.; Che, L.; et al. Dietary fiber during gestation improves lactational feed intake of sows by modulating gut microbiota. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2023, 14, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, M.; Chen, J.; Liu, J.; Chen, F.; Guan, W.; Zhang, S. Dietary fiber and microbiota interaction regulates sow metabolism and reproductive performance. Anim. Nutr. 2020, 6, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greiner, L.L.; Humphrey, D.C.; Holland, S.N.; Anderson, C.J.; Schmitz-Esser, S. The validation of the existence of the entero-mammary pathway and the assessment of the differences of the pathway between first and third parity sows. Transl. Anim. Sci. 2022, 6, txac047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prete, R.; Long, S.L.; Gallardo, A.L.; Gahan, C.G.; Corsetti, A.; Joyce, S.A. Beneficial bile acid metabolism from Lactobacillus plantarum of food origin. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Chun, S.H.; Cheon, Y.-H.; Kim, M.; Kim, H.-O.; Lee, H.; Hong, S.-T.; Park, S.-J.; Park, M.S.; Suh, Y.S.; et al. Peptoniphilus gorbachii alleviates collagen-induced arthritis in mice by improving intestinal homeostasis and immune regulation. Front. Immunol. 2024, 14, 1286387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Ramos-Roman, M.A.; Deng, Y. Metabolic adaptation in lactation: Insulin-dependent and independent glycemic control. J. Transl. Intern. Med. 2022, 10, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öner Sayar, C.; Köseoğlu, S.Z.A. Evaluation of the effect of different diets applied to breastfeeding mothers on the composition and quantity of human milk. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2025, 79, 660–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picciano, M.F. Pregnancy and lactation: Physiological adjustments, nutritional requirements and the role of dietary supplements. J. Nutr. 2003, 133, 1997S–2002S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maradiaga, R.; Mussad, S.; Yearsley, M.; Chakraborty, S. Unveiling the culprit: Sarcina infection in the stomach and its link to unexplained weight loss. Cureus 2023, 15, e44565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Su, Y.; Zhu, W. Microbiome-metabolome responses in the cecum and colon of pig to a high resistant starch diet. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.; Zheng, J.; Wu, X.; Xu, X.; Jia, G.; Zhao, H.; Chen, X.; Wu, C.; Tian, G.; Wang, J. Putrescine enhances intestinal immune function and regulates intestinal bacteria in weaning piglets. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 4134–4142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, G.; Ma, S.; Zhu, Z.; Su, Y.; Zoetendal, E.G.; Mackie, R.; Liu, J.; Mu, C.; Huang, R.; Smidt, H.; et al. Age, introduction of solid feed and weaning are more important determinants of gut bacterial succession in piglets than breed and nursing mother as revealed by a reciprocal cross-fostering model. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 18, 1566–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Vries, H.; Smidt, H. Microbiota development in piglets. In The Suckling and Weaned Piglet; Farmer, C., Ed.; Brill: Wageningen Academic: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 179–205. [Google Scholar]

- Law, K.; Lozinski, B.; Torres, I.; Davison, S.; Hilbrands, A.; Nelson, E.; Parra-Suescun, J.; Johnston, L.; Gomez, A. Disinfection of maternal environments is associated with piglet microbiome composition from birth to weaning. mSphere 2021, 6, e00663-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gestation | Lactation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | Control | Treatment | Control | Treatment |

| Corn, yellow dent | 58.72 | 58.17 | 66.39 | 65.84 |

| Soybean meal, dehull, solv. extr. (46% CP) | 8.00 | 8.00 | 18.00 | 18.00 |

| DDGS 1, >6 and <9% oil | 15.00 | 15.00 | 10.00 | 10.00 |

| CWG 2 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 1.50 | 1.50 |

| Limestone | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.40 | 1.40 |

| Monocalcium phosphate | 1.60 | 1.60 | 1.20 | 1.20 |

| Soybean hulls | 12.50 | 12.50 | -.- | -.- |

| Salt | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| Swine breeder pmx 3 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| L-Lysine HCl (78%) | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.40 | 0.40 |

| L-Threonine (98.5%) | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.08 |

| L-Tryptophan (98%) | -.- | -.- | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| L-Valine (97.5%) | -.- | -.- | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Feed sanitizer 4 | -.- | 0.55 | -.- | 0.55 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Calculated Nutrient Content, % | ||||

| Control Gestation | Control Lactation | |||

| NE, kcal/kg | 2365 | 2494 | ||

| Ca% | 0.75 | 0.89 | ||

| P, total% | 0.66 | 0.66 | ||

| Na% | 0.21 | 0.27 | ||

| STTD 5 P% | 0.45 | 0.42 | ||

| Crude protein | 14.35 | 17.22 | ||

| Crude fiber | 7.3 | 2.9 | ||

| SID 6 Arg | 0.66 | 0.90 | ||

| SID His | 0.32 | 0.40 | ||

| SID Ile | 0.44 | 0.57 | ||

| SID Leu | 1.22 | 1.40 | ||

| SID Lys | 0.69 | 0.98 | ||

| SID Met | 0.22 | 0.25 | ||

| SID Met + Cys | 0.42 | 0.49 | ||

| SID Phe | 0.57 | 0.71 | ||

| SID Thr | 0.42 | 0.58 | ||

| SID Trp | 0.10 | 0.16 | ||

| SID Val | 0.53 | 0.68 | ||

| SID Lys/NE, g/Mcal | 2.90 | 3.93 | ||

| Date Sampled | Diet Sampled | Expected Dose (kg/metric ton) | Actual Dose Recovered (kg/metric ton) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 21/8/23 | Gestation batch #1 | 5.5 | 6.22 |

| 20/9/23 | Lactation batch #1 1 | 5.5 | 7.86 |

| 28/9/23 | Lactation batch #1 (resample) 2 | 5.5 | 6.85 |

| 28/9/23 | Lactation batch #2 1 | 5.5 | 7.57 |

| 9/10/23 | Lactation batch #1 (resample) 2 | 5.5 | 5.43 |

| 9/10/23 | Lactation batch #2 (resample) 2 | 5.5 | 6.63 |

| Diet | p-Value | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trait | Control | Treatment 1 | Pooled SEM 2 | Trt 3 | Time | Trt × Time 4 | Initial BW 5 | Parity |

| No. of sows | 53 | 54 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Parity | 2.1 | 2.4 | 0.568 | 0.511 | - | - | - | - |

| Lactation length, days | 19.8 | 19.9 | 0.257 | 0.440 | 0.791 | |||

| Feed intake, kg | 1.518 | 0.960 | <0.001 | 0.995 | 0.625 | 0.029 | ||

| Wk 1 | 33.6 | 33.9 | ||||||

| Wk 2 | 53.0 | 52.5 | ||||||

| Wk 3 | 43.7 | 43.8 | ||||||

| Total lactation intake | 130.7 | 130.3 | 4.169 | 0.934 | 0.019 | |||

| Average daily feed intake, kg | 0.326 | 0.811 | <0.001 | 0.965 | 0.913 | 0.009 | ||

| Wk 1 | 7.57 | 7.48 | ||||||

| Wk 2 | 7.57 | 7.48 | ||||||

| Wk 3 6 | 7.60 | 7.50 | ||||||

| Overall (farrow to wean) | 6.6 | 6.6 | 0.217 | 0.849 | 0.038 | |||

| Sow lactation feed efficiency 7 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 0.070 | 0.076 | 0.402 | |||

| Sow body weight, kg | 1.770 | 0.002 | <0.001 | 0.568 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Pre-treatment | - | - | ||||||

| Day 109 of gestation | 244.2 | 240.2 | ||||||

| 24 h post-farrow | 231.1 | 228.1 | ||||||

| Weaning | 228.9 | 222.3 | ||||||

| Sow body weight change, kg | ||||||||

| Gestation body weight change | 19.2 | 16.2 | 1.442 | 0.218 | 0.624 | |||

| Farrowing body weight change | −13.1 | −12.0 | 1.293 | 0.550 | 0.562 | |||

| Lactation body weight change | −1.8 | −6.2 | 2.135 | 0.067 | 0.004 | |||

| Sow backfat depth, mm | 0.358 | 0.292 | <0.001 | 0.964 | <0.001 | 0.952 | ||

| Day 80 of gestation | 10.8 | 11.0 | ||||||

| Day 109 | 11.3 | 11.7 | ||||||

| 24 h | 11.0 | 11.4 | ||||||

| Weaning | 9.7 | 9.8 | ||||||

| Sow caliper | 0.281 | 0.345 | <0.001 | 0.792 | <0.001 | 0.194 | ||

| Gestation | 14.2 | 12.4 | ||||||

| Weaning | 14.0 | 12.1 | ||||||

| Sow caliper change | −1.7 | −2.0 | 0.285 | 0.489 | <0.001 | |||

| Diet | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Trait | Control | Treatment 1 | p-Value |

| Total sows weaned | 53 | 54 | -.- |

| Weaning-to-estrus interval to 7 d | 52 2 | 51 | 0.317 3 |

| Weaning-to-estrus interval to 14 d | 52 | 51 | |

| Weaning-to-estrus interval to 21 d | 52 | 51 | |

| Diet | p-Value | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trait | Control | Treatment 1 | Pooled SEM 2 | Trt 3 | Time | Trt × Time 4 | Initial BW 5 | Parity |

| No. of litters | 53 | 54 | ||||||

| Litter size, n | 0.319 | 0.102 | <0.001 | 0.739 | 0.234 | 0.001 | ||

| Total born alive | 14.1 | 14.8 | ||||||

| After cross-fostering | 13.6 | 14.0 | ||||||

| Weaning | 12.6 | 12.8 | ||||||

| Piglets per litter, n | ||||||||

| Total born | 16.7 | 16.4 | 0.434 | 0.571 | 0.392 | |||

| Mummies | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.137 | 0.120 | 0.528 | |||

| Stillborn | 1.8 | 1.2 | 0.283 | 0.048 | 0.142 | |||

| Piglet mortality before cross-fostering | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.193 | 0.229 | 0.656 | |||

| Piglet mortality after cross-fostering | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.219 | 0.593 | 0.195 | |||

| Piglet mortality, % | ||||||||

| After cross-fostering 6 | 4.4 | 4.2 | 1.278 | 0.953 | 0.450 | |||

| Litter weight, kg | 0.923 | 0.987 | <0.001 | 0.825 | 0.004 | 0.059 | ||

| Total born alive | 20.5 | 20.9 | ||||||

| Total after cross-fostering | 20.0 | 20.3 | ||||||

| Weaned | 78.4 | 77.8 | ||||||

| Litter weight, kg | ||||||||

| Mummies | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.071 | 0.325 | 0.979 | |||

| Stillborn | 2.2 | 1.2 | 0.347 | 0.008 | 0.259 | |||

| Transferred off | 2.1 | 1.8 | 0.585 | 0.381 | 0.610 | |||

| Dead pigs before cross-fostering | 1.2 | 1.8 | 0.439 | 0.145 | 0.192 | |||

| Average piglet weight, kg | ||||||||

| Born alive | 1.5 | 1.4 | 0.026 | 0.247 | 0.679 | |||

| Stillborn | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.086 | 0.059 | 0.534 | |||

| Dead pigs after cross-fostering 7 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.234 | 0.340 | 0.820 | |||

| Litter weight gain, kg 8 | 58.4 | 57.4 | 1.314 | 0.574 | 0.408 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Williams, S.; Domingues, F.; Manu, H.; Gomez, A.; Johnston, L. Effects of a Feed Sanitizer in Sow Diets on Sow and Piglet Performance. Animals 2025, 15, 3618. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243618

Williams S, Domingues F, Manu H, Gomez A, Johnston L. Effects of a Feed Sanitizer in Sow Diets on Sow and Piglet Performance. Animals. 2025; 15(24):3618. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243618

Chicago/Turabian StyleWilliams, Sara, Francisco Domingues, Hayford Manu, Andres Gomez, and Lee Johnston. 2025. "Effects of a Feed Sanitizer in Sow Diets on Sow and Piglet Performance" Animals 15, no. 24: 3618. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243618

APA StyleWilliams, S., Domingues, F., Manu, H., Gomez, A., & Johnston, L. (2025). Effects of a Feed Sanitizer in Sow Diets on Sow and Piglet Performance. Animals, 15(24), 3618. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243618