2. Materials and Methods

The study was undertaken at The University of Queensland’s large animal research facility, Queensland Animal Science Precinct, located in Southeast Queensland, Australia (27.54° S, 152.34° E; 100 m above mean sea level) during a southern hemisphere summer (December to April).

2.1. Animals and Animal Management

A total of 48 purebred yearling Black Angus steers with an initial non-fasted live weight of 539.53 ± 4.95 kg were used in a 21-day climate control study. Steers were randomly allocated into four cohorts consisting of 12 steers per cohort. Steers were randomly allocated to three dietary treatments (described below), thus there were four steers per treatment within each of the four cohorts. Steers in each cohort were group-housed (n = 12) in singular feedlot pens (162 m2, 27 m × 6 m) per cohort for 50 days, prior to entry into the climate control chambers. Steers were relocated from group-housed feedlot pens to individual pens (30 m2, 3 × 10 m) on d −10 and housed in individual pens for the 10 days directly prior to entry into the climate control chambers, respectively, for each of the four cohorts.

Animal observational data were collected on each individual steer at 2 h intervals between 6:00 am and 6:00 pm on days 3, 4, 6, 7 and d 8; and on days 13, 14, 15, 16, 18, 19 and 20 (data not reported here). Observational data were then obtained at 1 h intervals over 24 h (from 12:00 am to 11:00 pm, daily) on day 5, during the simulated heat wave event over days 9 to 13 and on day 17 (data not reported here). At each observation, cattle were observed for panting score; respiration rate (RR); posture (standing/lying); and activity (eating/drinking/ruminating) (data not reported here).

Individual steer non-fasted liveweight was obtained using calibrated scales and load beams (Gallagher, Melbourne, Australia) on entry into the climate control chambers (d 0) at 7:00 am and on exit (d 20) at 6:30 pm, with individual steer average daily gain (kg/steer/d) determined. On enrolment into this study and entry to the climate control chambers, steers were 60 days on feed.

Steers were vaccinated for clostridial diseases (enterotoxaemia, tetanus, blacks disease, malignant oedema and blackleg; Ultravac 5 in1; Pfizer Animal Health, Sydney, Australia), bovine respiratory disease (Bovillis MH, in-activated Mannheimia haemolytica; Coopers Animal Health, Sydney, Australia) and were treated for internal and external parasites (Cydectin, Fort Dodge Australia, Baulkham Hills, NSW, Australia) 10 days prior to feedlot entry, 69 days prior to the commencement of this study. Steers received a secondary bovine respiratory disease vaccination on d −46 (Bovillis MH, in-activated Mannheimia haemolytica; Coopers Animal Health, Australia). All steers were implanted with a hormonal growth promotant on d −60 (Synovex® Plus, 200 mg trenbolone acetate + 28 mg estradiol benzoate, Zoetis, Sydney, Australia).

Steers were part of a larger 165-day study (data not presented here). On exit from the climate control chambers, all steers were group-housed (n = 12) in a singular feedlot pen (162 m2, 27 m × 6 m) for 22 days until slaughter at a commercial abattoir.

2.2. Climate Control Chambers

Two climate control chambers were using in this study. The climate control chambers were configured in such a way that there were three individual animal pens (6.25 m2; 2.5 × 2.5 m) on each side of the climate control chamber, thus housing 6 steers per chamber. Each individual animal pen was constructed of four metal cattle panels and were constructed over a grated platform floor, allowing for easy cleaning and drainage. The grated flooring was covered with a rubber mat (SureFoot® Mat, 1.22 m × 1.83 m, 1.8 cm thickness; RPS Industries Australia, Melbourne, Australia) to improve animal comfort. The pen design did not restrict animal movement, steers were able to freely turn around, lay down, self-groom and have visual contact with conspecifics housed within the same chamber, but were unable to physically touch their conspecifics.

Each steer was provided with individual ad libitum access to a water trough (700 mm length × 500 mm width × 280 mm depth) fitted with an inline water metre (RMC Zenner, Melbourne, Australia). Steers also had individual access to a feed trough (500 mm length × 500 mm width × 500 mm depth). The climate control chambers were cleaned daily at 0830 h prior to feeding (described below) by hosing all excrement from the mats and pen flooring into the drainage system below the grated flooring.

2.3. Climatic Conditions

Steers were exposed to a simulated Australian summer that was established from 5 years of historical weather data (Dalby, Qld; 27.19° S, 151.27° E), which included the minimum, maximum and mean data for ambient temperature (°C) and relative humidity (%), obtained from the Australian Bureau of Meteorology (

www.bom.gov.au). From these data, the temperature humidity index (THI) was calculated using the equation below, as modified from Thom [

23]:

Climatic data was used to create a climate schedule to simulate both average summer and a 5-day heat wave event throughout the 21-day study. The study was split into five Phases consisting of pre-heat wave conditions (i) Phase I and Phase II, where the THI ranged between 65 and 78, ambient temperature was maintained between 19 and 31 °C and RH was held between 40 and 80%, over the period encompassing d 0 to d 8. Phase III imposed the acute heat wave conditions where the THI ranged between 83 and 90, ambient temperature was maintained between 30 and 40 °C, with relative humidity held between 45 and 80%, over d 9 to d 11. Imposed ambient conditions then decreased slightly during Phase IV, where the THI ranged between 78 and 85, where ambient temperature was maintained between 28 and 36 °C and relative humidity held between 45 and 70%, over d 12 and d 13. During the post-heat wave conditions, Phase V, the ambient conditions returned to baseline summer conditions, where the THI ranged between 65 and 78, ambient temperature was maintained between 19 and 31 °C and relative humidity was held between 40 and 80%, over d 14 until exit from the climate control chambers on d 20.

The climate schedule during Phase I and Phase II followed a diurnal pattern reaching a maximum of 31 °C, 40% RH, resulting in a corresponding THI of 78 during daytime hours (6:00 am to 6:00 pm) and a maximum 19 °C, 80% RH, and a THI of 65 during nighttime hours (6:00 pm to 6:00 am). During Phase III, during the heat wave between d 9 and d 11, climatic conditions during daytime hours reached a maximum 40 °C, 45% RH, and a THI of 90, and a corresponding nighttime maximum of 30 °C, 80% RH, imposing a THI of 83. Throughout Phase IV, covering d 12 and d 13, climatic conditions imposed consisted of a maximum 36 °C, 45% RH, resulting in a THI of 85 during daytime hours, and a maximum 28 °C, 70% RH, and a THI of 78 during nighttime hours. The climate regime for Phase V was scheduled to be the same conditions as those imposed during Phase I and Phase II as described above. The lighting schedule involved 100% lighting from 5:01 am to 6:59 pm and 10% lighting (moonlight) from 7:00 pm to 5:00 am daily.

2.4. Nutritional Management

The steers were fed twice daily at approximately 9:00 am and 1:00 pm with 50% of the ration provided at each feed offering. At 8:30 am, immediately prior to the 9:00 am feeding, any feed refusals were removed and weighed, these data were used to determine daily as fed feed intake (kg/steer/d) and dry matter intake (kg/steer/d) based on dry matter % of the diet from dietary analysis (

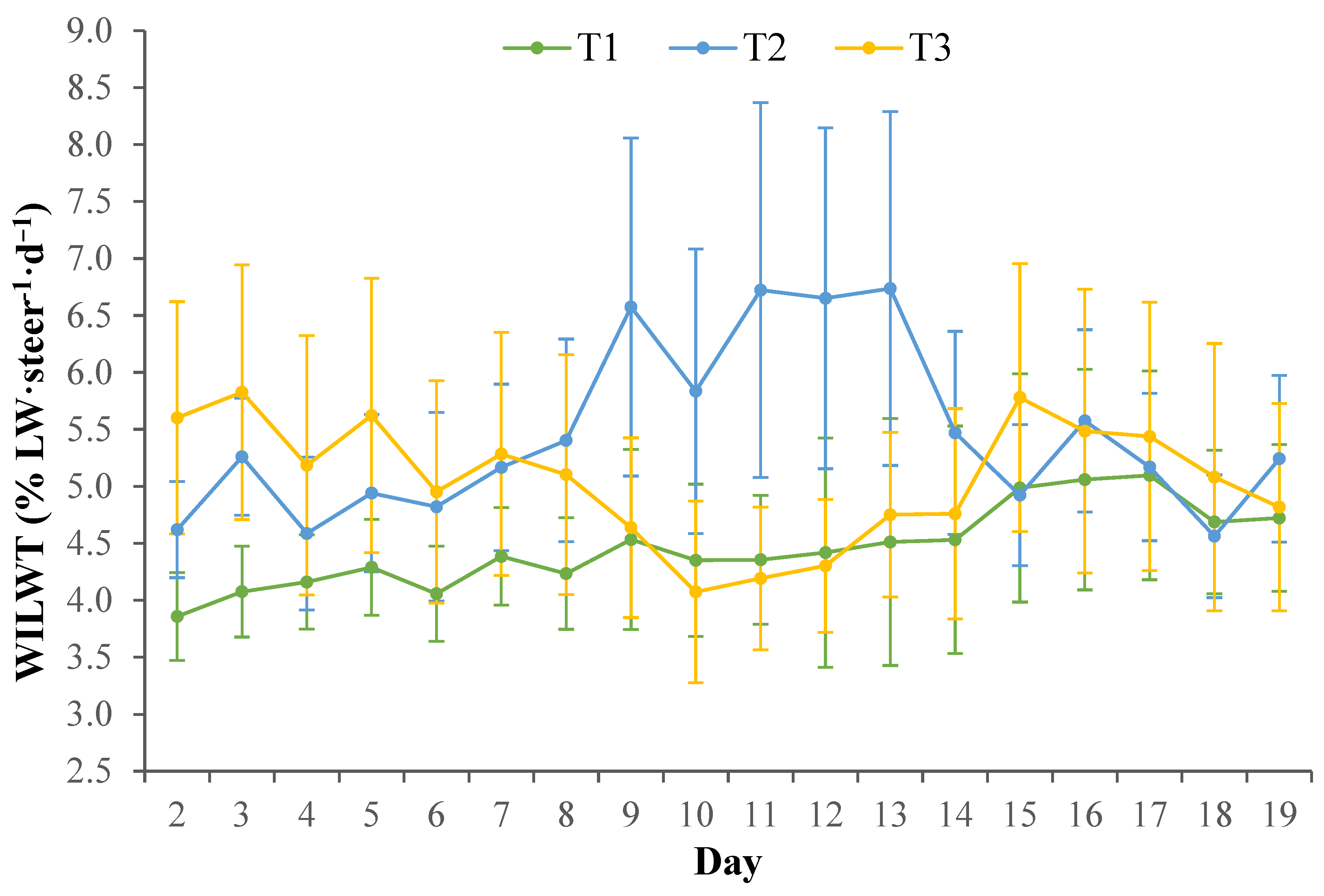

Table 1). Individual feed allocation was allocated based on each individuals’ feed consumption from the day prior and managed throughout the duration of the study, with careful consideration during the heat wave challenge during Phase III between day 9 and 11. Using individual steer dry matter intake and liveweight data from d 0, the dry matter intake as a proportion of LW was determined (DMILW; % LW/steer/d). Water metre readings were recorded daily at 6:00 am; from these, data individual water intake (L/steer/d) and water intake as a proportion of liveweight, obtained from d 0, were determined (WILW; % LW/steer/d). All water troughs were cleaned, emptied and refilled as required. The total water removed and refilled for each cleaning event from each individual water trough was subtracted from the daily water intake for each respective steer.

Each cohort was commenced on a dietary transition protocol that allowed for the transition from a pasture-based diet to feedlot finisher ration while each respective cohort was housed as a group in feedlot pens during the 60 days prior to feedlot entry. Steers commenced on a starter ration on entry to the feedlot on d −60, were transitioned to an intermediate ration on d −53 and then to a finisher diet on d −46 (

Table 1). While housed in the climate control chamber, three dietary management treatments were implemented: Treatment 1 (T1) cattle were fed a finisher diet for the 21 days; Treatment 2 (T2) cattle were transitioned from the finisher diet to a heat load diet (

Table 1) on d 9 and remained on this diet until d 14; and Treatment 3 (T3) cattle were transitioned from the finisher diet to the heat load diet on d 7 and remained on this diet until d 14 (T3). Steers that were transitioned onto the heat load diet in T2 and T3 commenced transitioning back to the standard finisher diet on d 15. This transition to the standard finisher diet occurred using a step-up protocol where on d 15, T2 and T3 were fed 70% heat load diet and 30% finisher diet, then on d 16 and d 17 steers were 50% heat load diet and 50% finisher diet, then returning to 100% finisher diet on d 18.

Dietary formulation was influenced by ingredient availability. Lucerne hay was used to increase the roughage proportion of the heat load diet as this was readily available and cost-effective. Diets were prepared on site at one-month intervals in a commercial grade mixing wagon (Kuhn Euromix II 1860, Saverne, France). Because of this, ingredients needed to be sourced so that dry diets could be formulated and easily stored until use between mixings. A 500 g grab sample was collected from each diet mixing by collecting sub-samples of the mixed sections. Diet samples were frozen at −20 °C until analysis, which was conducted at the end of the larger study experimental period. Each dietary sample was analysed by a commercial analytical laboratory (Symbio Laboratories, Brisbane, OLD, Australia,

Table 1).

2.5. Rumen Temperature and Rumen pH

Steers were orally administered with an active radio frequency identification (RFID) transmitting rumen bolus (smaXtec pH Plus Bolus, smaXtec, Graz, Austria) on d −10. Individual boluses were cylindrical in shape (132 mm length × 35 mm diameter) and weighed approximately 220 g. Prior to administration, the smaXtec boluses were checked for temperature stability by placing them in a 39 °C water bath for 24 h. Prior to this, rumen boluses were calibrated by placing boluses in a pH 4 solution for 8 h and then another 8 h in a pH 7 solution, as per manufacturer specifications. Rumen temperatures and ruminal pH were recorded at 10 min intervals, from 24 h after they were orally administered. These data were communicated real-time to a base station (smaXtec Base Station, smaXtec, Austria) before transmission to a data server and storage in an online data base (smaXtec Messenger, smaXtec, Austria). Rumen boluses were recovered from all cattle post-slaughter.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Six steers were removed from study during the first 2 days of Phase III due to an adverse response to conditions; specifically, steers exhibited a combination of highly agitated/distressed behaviours (sunken eyes, lack lustre appearance, vocalisation), TRUM > 42 °C, RR > 160 bpm, panting score ≥ 3.5, acute acidosis symptoms, hypersalivation, rumen pH > 5.0, ceased/very low DMILW and WILW. Three of these steers were from T1 and three were from T2; as such, data from these steers was excluded from statistical analysis.

All data were analysed using R3.6.2 software (R, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Day 0 and d 1 was used as an opportunity for all the steers to acclimate to the climate control chamber, and as such, data during this time was omitted. In addition, d 20 was also omitted.

Each day was considered to go over a 24 h period that encompassed the period between 6:00 am and 5:59 am to coincide with behavioural observational data collection (data not presented here).

Days of the study were then split into the five Phases for comparison of animal data based on transition to diets and climate schedule as previously described.

Rumen variables were investigated as duration of time (DUR, h/d) and magnitude (AUC, area under the curve; AAC, area above the curve) above T

RUM and below rumen pH thresholds of biological importance (described below). The AUC and AAC were estimated using the Trapezoid Rule. Rumen temperature variables were calculated above the 42 °C body temperature threshold at which homeostatic systems within the body reach their upper critical limits for normal function, as described by Mehla et al. [

24]. From this, T

RUM variables included DUR > 42 °C and AAC. Rumen pH variable thresholds of 5.0 and 5.6 were assigned based on work by Nagaraja and Titgemeyer [

25], where rumen pH below 5.0 was considered to be acutely acidotic and between 5.0 and 5.6 were considered to be sub-acutely acidotic. From this, rumen pH variables included DUR and AUC below acute rumen acidosis threshold (ARA; pH < 5.0, h/d), and DUR and AUC within subacute rumen acidosis range (SARA; pH < 5.6, ≥ 5.0, h/d). The rumen pH AUC for SARA and ARA, as well as AAC for T

RUM DUR > 42 °C, were calculated for each individual animal ID and then averaged values were used for comparisons across Treatment, Day and Phase.

For TRUM and rumen pH data, a linear mixed effects model with a first order auto-regressive error structure was used with fixed effects for pen, cohort, Treatment, Phase, Day, grouped by interaction including Treatment × Phase, Treatment × Day and Treatment × Phase × Day, with animal ID incorporated as a random effect. Range in TRUM and rumen pH was calculated as mean differences between hourly maximum and minimum for each steer within each Treatment.

Animal live weight and average daily gain data were analysed using a mixed effects model that considered pen, cohort and Treatment as the fixed effects and animal ID incorporated as a random effect. Liveweight for DMILW and WILW was determined using the climate chamber entry weight recorded on d 0 for each individual steer. For DMILW and WILW, a linear mixed effects model with a first order ante-dependence covariance structure was used with fixed effects for pen, cohort, Treatment, Phase, Day, grouped by interaction including Treatment × Phase, Treatment × Day and Treatment × Phase × Day, with animal ID incorporated as a random effect.

The DMILW were calculated for each steer using the following equation:

The WILW was calculated for each steer using the following equation:

The ADG was calculated for each steer using the following equation:

Denominator degrees of freedom for statistical tests were calculated using the Kenward–Roger method. Mean values are termed significantly different where p ≤ 0.05.

4. Discussion

Within the current study, a 66.07% to 77.67% reduction in DMILW was observed during the heat wave conditions, regardless of the dietary treatments provided, which is consistent with previous studies [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30]. Kahl et al. [

31] concluded that during periods of high heat load, decreases in feed intake are associated with the animal attempting to reduce metabolic heat production as a mechanism to maintain homeostasis. Within the current study, the mean DMILW of the T2 steers during Phase IV was comparatively lower when compared with the T3 steers and tended to be lower than T1 steers. The lower DMILW of T2 may be associated with the sudden dietary change to the heat load diet that occurred on d 9. This sudden change in diet may have prevented these steers from acclimating to the new diet, preventing ruminal adaptions before the onset of the thermal challenge, likely adding an additional stressor to the steers in T2. It is probable that this resulted in a rapid alteration in the rumen environment from the combination of dietary change in conjunction with the onset of heat wave conditions. Previously, Sejian et al. [

32] evaluated the cumulative impact of multiple stressors (nutritional, thermal and locomotory) on the adaptive capability of rams. Outcomes from this study highlighted that the cumulative effect of these stressors negatively influenced feed intake, body temperature and general animal well-being, when compared with rams that had been exposed to a singular heat stressor.

Daily DMILW was greatly affected by the onset of Phase III, with feed consumption markedly decreasing until d 11, when mean minimum DMILW occurred for all Treatments. It is generally accepted that 3 to 4 days are needed after the onset of a heat event for cattle to begin to acclimatise and achieve a new level of heat balance [

2]. At the onset of Phase IV, on d 12, DMILW began to increase for all Treatments, which coincided with a reduction in daily maximum ambient temperature by 4 °C, providing an opportunity to dissipate some accumulated heat load, as evidenced by decreases in mean T

RUM of between 0.47 and 0.69 °C. The severe decreases in DMILW, as well as exposure to the acute heat wave conditions, resulted in very low, although not unexpected, average daily gain. Despite the strong interaction of Treatment × Phase for DMILW, average daily gain was not affected by Treatments. Rhoads et al. [

33] showed that decreased feed intake led to a favoured mobilisation of nutrients from peripheral tissues to compensate for subsequent increases in energy demands, rather than supporting anabolic and metabolic processors. This can partly explain why periods of heat stress are associated with decreases in average daily gain. Furthermore, typically, during heat wave events, there are large losses in body weight, which are associated with the decreased dry mater intake and the coinciding diversion of energy and nutrients away from growth and towards maintaining homeostasis [

33,

34]

Within the current study, the WILW for T1 and T3 tended to be greater during the heat wave conditions compared to pre-heat wave Phase I and Phase II, despite the heat load conditions increasing in intensity. It can be speculated that the mild heat load conditions during Phase I and Phase II may have influenced WILW, regardless of Treatments, so that WILW was already high due to the steers attempting to regulate their body temperature to facilitate evaporative heat loss and maintain homeostasis while exposed to chronic heat load conditions. This may in part be due to the dramatic decreases in DMILW negating the need for a greater water requirement for digestive processes. In comparison, the WILW for T2 clearly increased during the heat wave conditions compared with mean WILW pre-heat wave. Generally, water intake is primarily driven by dry matter intake and diet type, where previous studies have shown an increase in dry matter intake and diets with a higher roughage content are associated with an increase in water intake [

35,

36]. Despite this, the reasoning behind the comparatively greater WILW for T2 may be due to the direct effects of the heat wave conditions increasing water requirements for thermoregulatory mechanisms rather than being driven by dry matter intake and the greater roughage content of the heat load diet. Increased water intake during hot conditions can also be attributed to increases in water losses from peripheral vasodilation and evaporative cooling mechanisms, such as through increased respiration rate and panting, to regulate internal body temperature and the associated salivary losses that can occur with panting [

37,

38]. Water loss was not measured during this study; as such, the water lost between Treatments cannot be identified to verify the WILW differences. Furthermore, it is important to consider that on the respective d 7 and d 9 when T3 and T2 transitioned to the heat load diet, the DMILW and WILW of each Treatment was similar when compared with the previous day water intakes. This may indicate that the greater roughage content of the heat load diet did not influence the DMILW or WILW of the steers, possibly due to the roughage content only being increased by 8%, on an ingredient basis. Despite this, the greater WILW and lower DMILW of T2 during the heat wave conditions may be indicative of impaired thermoregulation in these animals, when compared with cattle in other Treatments and may not be due to the direct dietary effects.

Under thermoneutral conditions, it is generally considered that body temperature is regulated within a ± 1 °C gradient [

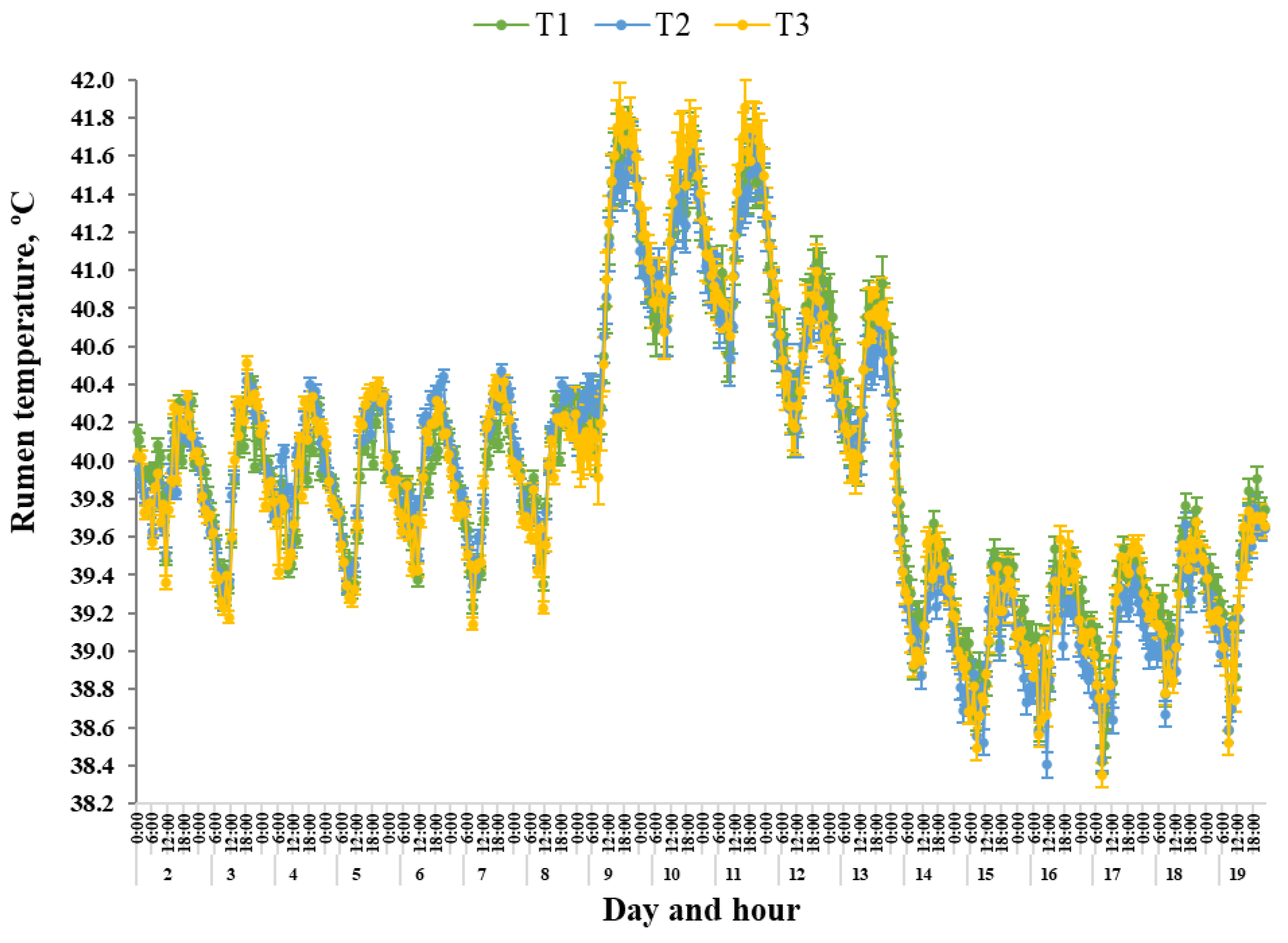

39]. Within the current study, increases in T

RUM, ranging between 0.8 and 1.01 °C, were observed for all Treatments when steers were transitioned from Phase II to the acute heat wave conditions during Phase III. Hahn [

2] and Wahrmund et al. [

40] suggested that disruptions to internal body temperature control during heat load periods can reflect thermal exchange imbalances between individual animals and the environment, as well as altered metabolic processors, activity level, feed and water intake levels and animal health status. The increased T

RUM within the current study may indicate that the thermoregulatory ability of these cattle became compromised during Phase III. Furthermore, there were no differences in T

RUM mean, range or DUR > 42 °C for Treatments, demonstrating that regulation of T

RUM was not influenced by the different dietary Treatments. Unsurprisingly, the T

RUM of all steers was influenced by Day and Phase, specifically during the acute heat wave conditions. The mean DUR > 42 °C and AAC increased, range in T

RUM decreased and the diurnal rhythm was altered. As such, it is likely that the acute heat wave conditions imposed during Phase III/Phase IV were likely to limit metabolic heat loss capabilities, as well as other heat dissipation thermoregulatory mechanisms, contributing to the greater heat load placed on these steers. This was evident as the proportion of time where T

RUM DUR > 42 °C was greatest during Phase III, with all steers having a T

RUM DUR > 42 °C for between 2.33 and 2.76 h per day. Previously, Mehla et al. [

24] concluded that an internal body temperature of ≥ 42 °C may result in the homeostatic systems within the body reaching their upper critical limits for normal function. Therefore, changes in T

RUM surpassing this 42 °C threshold could be considered to be representative of a failure of the animal to adapt to the heat challenge imposed in this study.

It has been well established that body temperature is not static and, as such, exhibits a diurnal rhythm [

41,

42,

43]. Variations in body temperature have been reported to range between 0.5 and 1.2 °C during moderate conditions, specifically, ambient temperatures of 30 ± 7 °C for tympanic temperature [

2], 0.5 to 1.4 °C during thermoneutral to moderate conditions, consisting of ambient temperatures between 18 ± 7 °C and 34 ± 7 °C, for rectal temperature [

26], and between 0.33 and 0.64 °C during heat wave conditions, where ambient temperature was > 35 °C, for T

RUM [

44]. These previous findings suggest that the range in body temperature appears to be largely dependent on ambient conditions, although the location body temperature is measured as well as individual animal, managerial and environmental factors that appear to contribute to the variability that exists. Within the current study, mean range in T

RUM was similar for all Treatments during the pre- and post-heat wave conditions, indicating that T

RUM fluctuated each day, regardless of Treatments. In comparison, during the heat wave conditions of Phase III/Phase IV, the range in T

RUM for all Treatments decreased. Furthermore, Hahn and Mader [

3] suggested that during heat load events, where ambient temperature was 32 ± 7 °C, the diurnal rhythm of body temperature becomes disrupted with peaks in maximum body temperature, typically lagging ambient conditions by 3 to 5 h. Similar lag periods were observed within the current study, with mean maximum T

RUM lagging ambient conditions by 4 to 7 h from when maximum heat load was imposed at 1300 h. There was also a clear alteration in daily diurnal rhythm during the heat wave where mean T

RUM minimum and maximum values occurred around 2 h earlier during the morning and around 2 h earlier during the late evening, respectively, irrespective of Treatment. However, these changes to body temperature rhythm may be confounded by the climate-controlled environment where natural outdoor conditions may support the thermal exchange pathways more efficiently when compared to chamber housing. Regardless, the altered rhythm in daily body temperature observed in this study is similar to previous heat load studies [

26,

41,

42,

45,

46]. Furthermore, these changes can be considered a reflection of heat accumulation and dissipation during heat load conditions. Lefcourt and Adams [

41] reported that this shift to increasing body heat dissipation during the earlier morning period could be attributed to a physiological reset mechanism that cattle employ in preparation for the onset of continued heat challenge with the commencement of a new day. Within the current study, despite thermal conditions cooling during Phase V, the T

RUM diurnal rhythm did not return to pre-heat wave rhythms, as recorded during Phase I and Phase II. This is in agreement with a previous study by Hahn and Mader [

3] and, more recently, Wijffels et al. [

29] and Sammes et al. [

30]. Wijffels et al. [

29], determined that this post-heat-wave reduced body temperature is an allostatic response to the heat challenge. This results in body temperature adjustments that stabilise around a new lower temperature, which drives new adjusted physiological state post-heat event [

29].

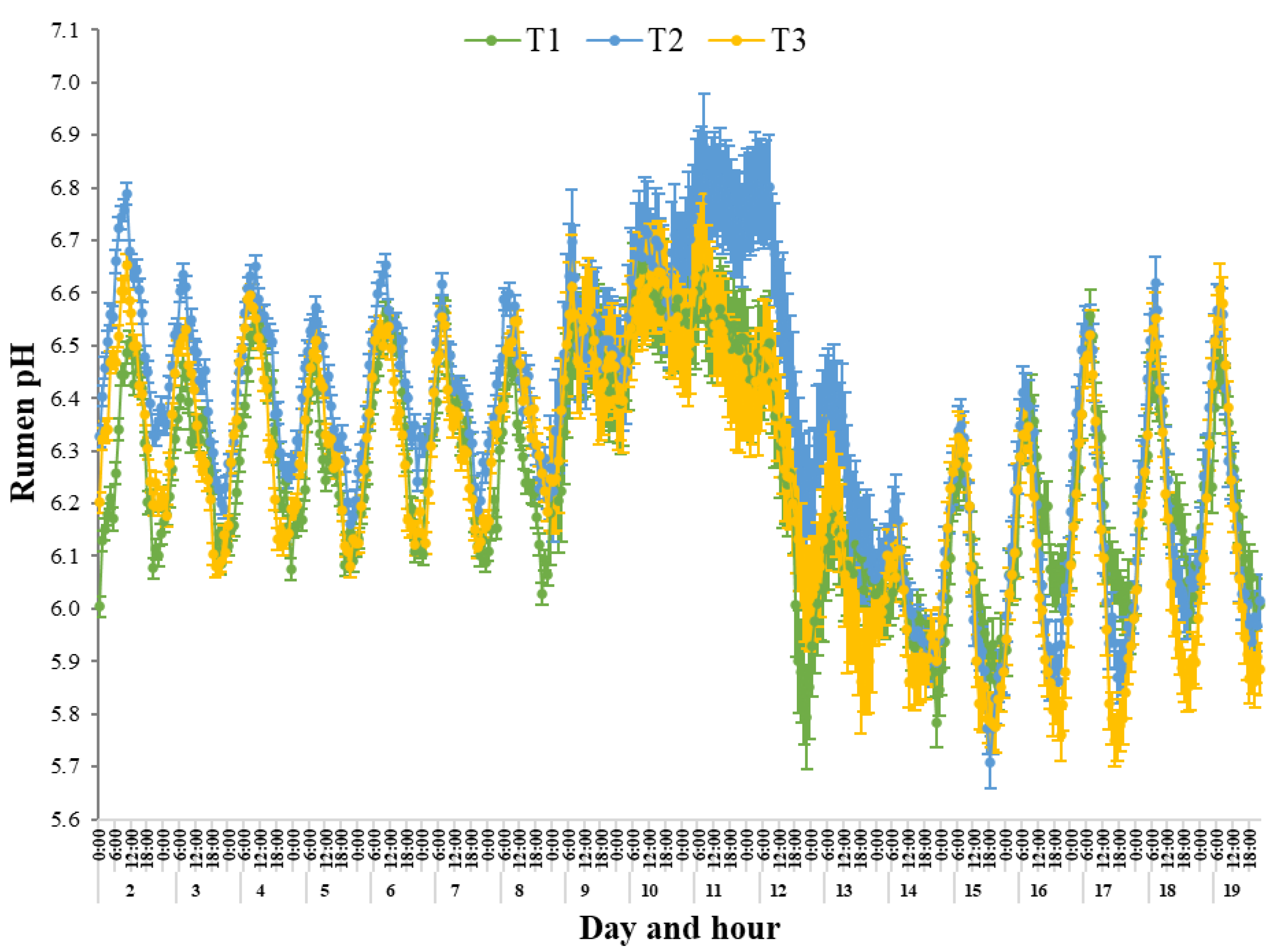

Within the current study, all Treatments had the greatest mean rumen pH during the first 3 days of the heat wave, which were during Phase III, compared with pre- and post-heat wave conditions, possibly associated with the very low DMILW. Generally, during periods of nutrient deprivation, the growth of some rumen microorganisms is inhibited, thus reductions in acid production can occur, resulting in an increase in rumen pH for extended periods [

47]. Furthermore, when a dual-flow, continuous-culture system was used to investigate effects of normal T

RUM (39 °C) and high T

RUM (41 °C) on in vitro fermentative conditions, the high T

RUM conditions increased (

p < 0.01) rumen pH [

48]. Conversely, in a study by Mishra et al. [

49], higher concentrations of lactic acid and lower rumen pH values were recorded for lactating dairy cows during heat stress (ambient temperature, 29.4 °C; relative humidity, 85%), which may be attributed to the feeding of high concentrate diets. Overall, this suggests that these altered concentrations of lactic acid and pH might be involved in inhibiting rumen motility with a negative influence on rumen health [

49]. A study by Crossland et al. [

50] reported that mean rumen pH of eight crossbred finishing steers (389 ± 30 kg) was lower (

p = 0.0029) during hot (ambient temperature, 35 ± 0.55 °C; relative humidity, 42%) compared with thermoneutral (ambient temperature, 18 ± 0.55 °C; relative humidity, 20%) conditions, although there was no difference in pH variation (

p = 0.3328). The authors speculated that during heat stress a slower rumen passage rate and decreased acid clearance within the rumen may be associated with the lower pH [

50]. Within the current study, the greater rumen pH of all Treatments could be attributed to the acute heat wave conditions, high T

RUM, increased WILW and low DMILW of the steers.

Within the current study, the T2 steers maintained comparatively greater rumen pH values during the heat wave conditions compared with T1 and T3. The tendencies for lower DMILW and greater WILW of T2 during the heat wave conditions is sufficient to suggest that these steers had greater rumen pH due to these altered feed and water intakes, when compared to the similar intake responses of T1 and T3. Interestingly, the rumen pH of T2 increased beginning from d 10, maintaining comparatively elevated pH values separated from the similar daily rumen pH trend, as seen for T1 and T3 up until d 13. Upon evaluation, the T2 steers maintained, on average, a rumen pH 0.21 times greater than the other Treatments during the heat wave, reaching a maximum divergence of mean daily pH on d 11, of which was 0.24 times greater compared with T1 and T3. The greater rumen pH recorded for T2 may indicate impaired rumen functionality due to the tendencies for lower DMILW and greater WILW diluting ruminal contents during the heat wave. This may suggest the dysregulation of rumen pH, WILW and DMILW separate from the trends seen for T1 and T3 may possibly be due to T2 transitioning to the heat load diet on the first day of Phase III, compounding the impact of heat stress. It is well known that the establishment of stable rumen microbial populations during dietary transition is not immediate [

51]. It is probable that the direct effects of the acute heat load conditions negatively impacted the ability of the steers to maintain metabolic stability and was confounded by the sudden dietary change and concurrent suppression of DMILW and increase in WILW. Despite this, the T2 steers spent a lower DUR within SARA and below ARA compared with T1. This may suggest that despite a possible compound effect of dietary transition coinciding with onset of the heat wave conditions, the greater roughage concentration of the heat load diet may be responsible for the reduced DUR below the ARA threshold for both T2 and T3 when compared with T1. A greater proportion of roughage in the diet can result in longer chewing times and greater saliva production, and thus bicarbonate buffer entering the rumen, which neutralises and dilutes ruminal acids, helping to reduce the risk of acidosis [

52,

53]. In the current study, rumen pH of all Treatments sharply declined 4 days after the onset of the heat wave conditions, which coincided with a reduction in mean T

RUM, an increase in DMILW after 3 days of near-ceased DMILW and decrease in heat load conditions. Generally, at the conclusion of heat wave conditions cattle generally compensate for low feed intake during the heat wave, typically via excessive consumption of feed. This excessive consumption of concentrates can result in accumulation of acid in the rumen, which lowers rumen pH and can contribute to causing a range of acidotic and metabolic problems [

17]. As a consequence of the acute heat wave conditions and subsequent 3 days of high T

RUM and nutrient deprivation from very low DMILW, followed by an increase in DMILW, this may have altered rumen function, negatively affected regulation of rumen pH and increased DUR spent below acidosis thresholds. Findings within the current study suggest that during the post-heat wave period of Phase V, the steers were unable to return to rumen pH conditions similar to the pre-heat wave conditions. This may suggest that irrespective of dietary Treatment, the imposed acute heat wave conditions may have negatively altered the ruminal environment, disrupting the functionality and regulation of rumen pH, as seen with the sharp decline in mean rumen pH during Phase IV. These disturbances to rumen pH appear to then remain and intensify during the post-heat wave period, despite DMILW increasing and T

RUM decreasing.

During Phase I and Phase II, the rumen pH was elevated during mid-morning, reaching a daily maximum between 8:00 am and 9:00 am and a daily minimum during the late evening, between 8:00 pm and 12:00 am for all Treatments. There was a notable disruption of the diurnal pH rhythm across all Treatments at the onset of the heat load conditions on d 9, whereas there was little evidence of a clear daily rhythm during Phase III and Phase IV. This may have been due to greater mean rumen pH, mean T

RUM and WILW, reduced range in rumen pH and low DMILW during the heat wave conditions. Despite this, the times of the day that rumen pH reached a daily minimum and maximum were similar to that recorded pre-heat wave, being elevated during mid-morning, between 0800 h and 0900 h, and a nadir in the late evening, although this was over a slightly extended time period between 7:00 pm and 3:00 am. Salfer et al. [

54] found that although differences in daily mean rumen pH were evident for different diets, including differing concentrations of starch, fatty acids and dietary fibre, there was no difference in the daily diurnal pattern of rumen pH. This is in agreement with the current study in that, unlike the T

RUM diurnal rhythm that became greatly disrupted in terms of when daily minimums and maximums occurred during each Phase, the daily rumen pH diurnal rhythm remained relatively unchanged throughout each Phase. Furthermore, the current study found there to be no difference in mean rumen pH between T1 and T3 during any Phase. Such data suggests that despite being fed different diets, this did not influence rumen pH; however, this may be due to the very low DMILW of the steers during the heat wave negating any dietary influence. In comparison, T2 maintained comparatively greater mean rumen pH during the heat wave conditions of which was particularly evident during Phase IV. The greater rumen pH of T2 during the heat wave may be associated with the sudden dietary change to the heat load diet on d 9, which tended to reduce DMILW and increase WILW compared with T1 and T3. From d 14, all Treatments evidently regained a clear pH diurnal rhythm within the preceding Phase V days as T

RUM and WILW decreased, and DMILW and range in rumen pH gradually increased.

During Phase V, all Treatment had the greatest time spent below SARA and ARA thresholds for Phase. Interestingly, steers in T2 had the lowest DUR within SARA range and below the ARA threshold, possibly due to the tendency for lower DMILW and greater WILW resulting in greater mean rumen pH during the heat wave. In comparison, steers in T3 spent the greatest DUR within SARA range during Phase IV and Phase V, with T1 having the greatest DUR below ARA range during Phase IV and Phase V, possibly due to the lower proportion of roughage in the finisher diet. The increased roughage content of the heat load diet may explain why the steers in both T2 and T3 spent a lower DUR below the ARA threshold. A greater proportion of roughage in the diet has been shown to result in longer chewing times and greater saliva production, thus bicarbonate entering the rumen, which neutralises and dilutes ruminal acids, helping to reduce the risk of acidosis [

52,

53]. Beatty et al. [

27] reported that after a hot period, cattle are not able to maintain homeostasis and metabolic disorders can develop, possibly due to inappetence during prolonged high heat load periods. In addition, Bernabucci et al. [

55] suggested that when high heat load conditions are removed and animals normalise their physiological response parameters and feed intakes, the functionality of the rumen environment remains impaired for 1 to 2 weeks. Furthermore, Crossland et al. [

50] reported that T

RUM greatly affects rumen pH and the duration and magnitude of SARA and ARA, possibly due to altered metabolism. Within the current study, the acute heat wave conditions were associated with a substantial variation in the rumen environment; when rumen temperature became elevated, the range in rumen pH decreased and a clear deviation from diurnal rhythm in rumen pH ceased. These ruminal disturbances may have negatively influenced regulation of rumen pH during the preceding 7 days into Phase V. This may partly explain why the greatest DUR spent below acidosis thresholds occurred during Phase V and is sufficient to suggest that acidosis in grain-fed beef steers appears to occur predominately during post-heat wave periods rather than during heat wave conditions, therefore suggesting that feeding a heat load diet during the post-heat wave period may address these ruminal disturbances and increased DUR spent below the ARA threshold. Within the current study, the increased roughage content of the heat load diet may have helped regulate rumen pH so that the occurrence of ARA was reduced for T2 and T3, which may improve animal performance in the long term. This is an area that warrants further investigation under large-scale commercial feedlot conditions to elucidate heat load diet timing efficacy in grain-fed steers during heat wave conditions. However, the foundational outcome from this study is that further work focusing on implementing feeding strategies during post-heat wave periods to support rumen recovery is vital.