A Bio-Economic Evaluation of Var, LnVar, and r-Auto Resilience Indicators in Czech Holstein Cattle

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Initial Dataset and Resilience Indicator Quartiles

2.2. Animal Performance and Herd Structure

2.3. Bio-Economic Analyses

3. Results

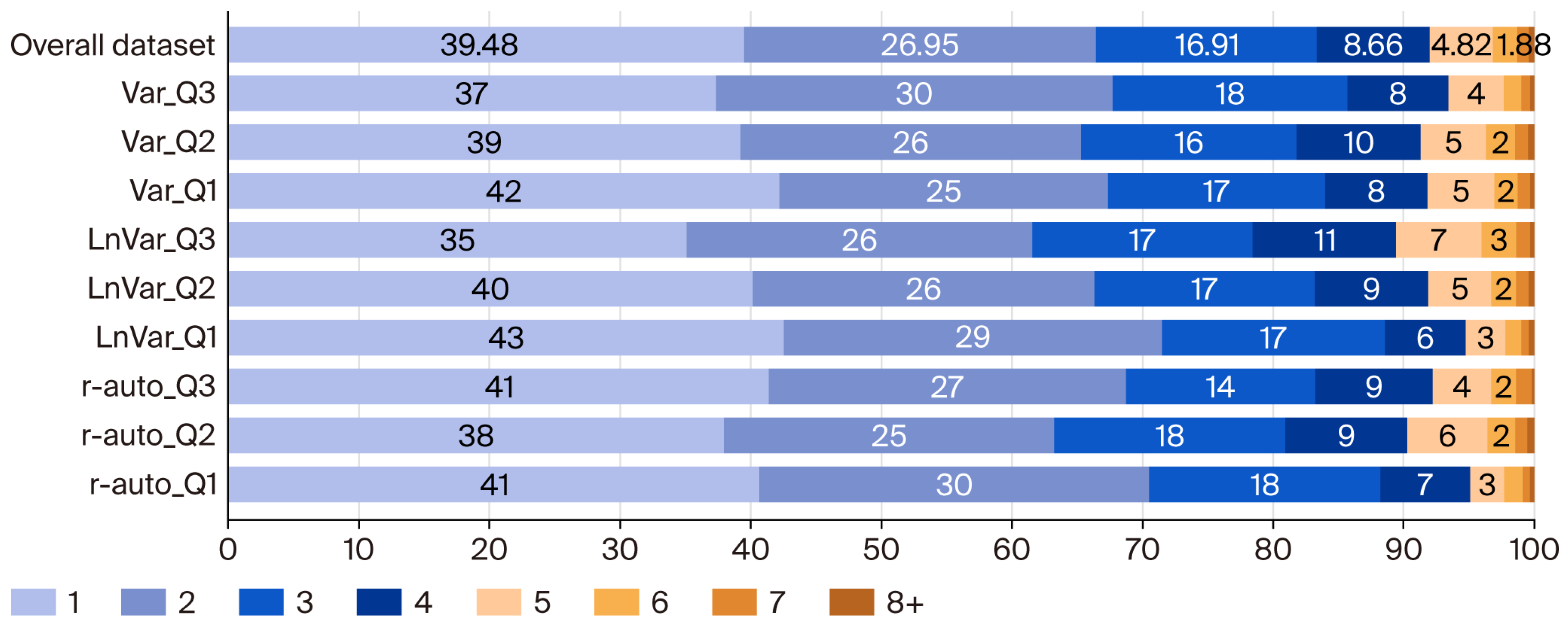

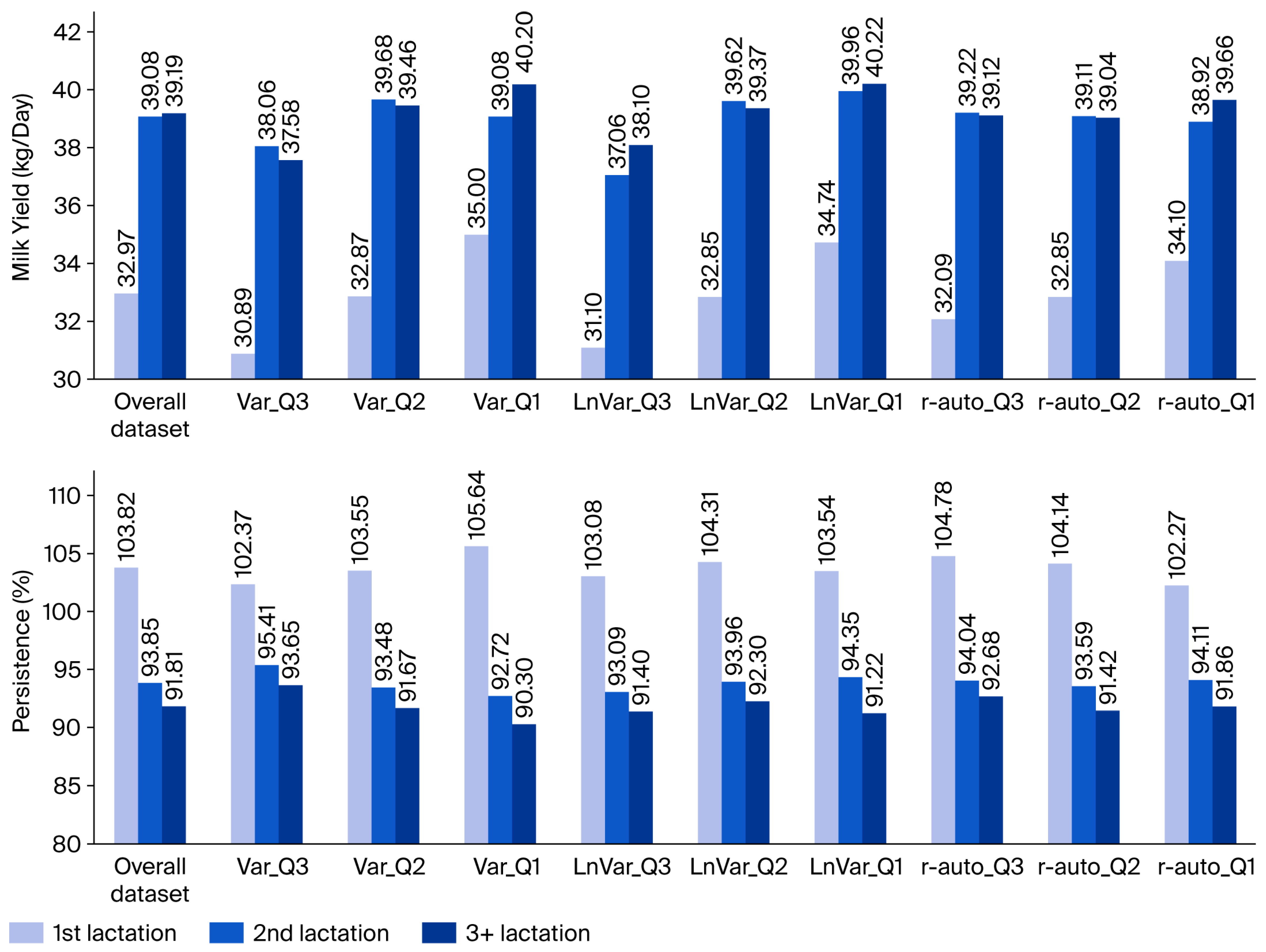

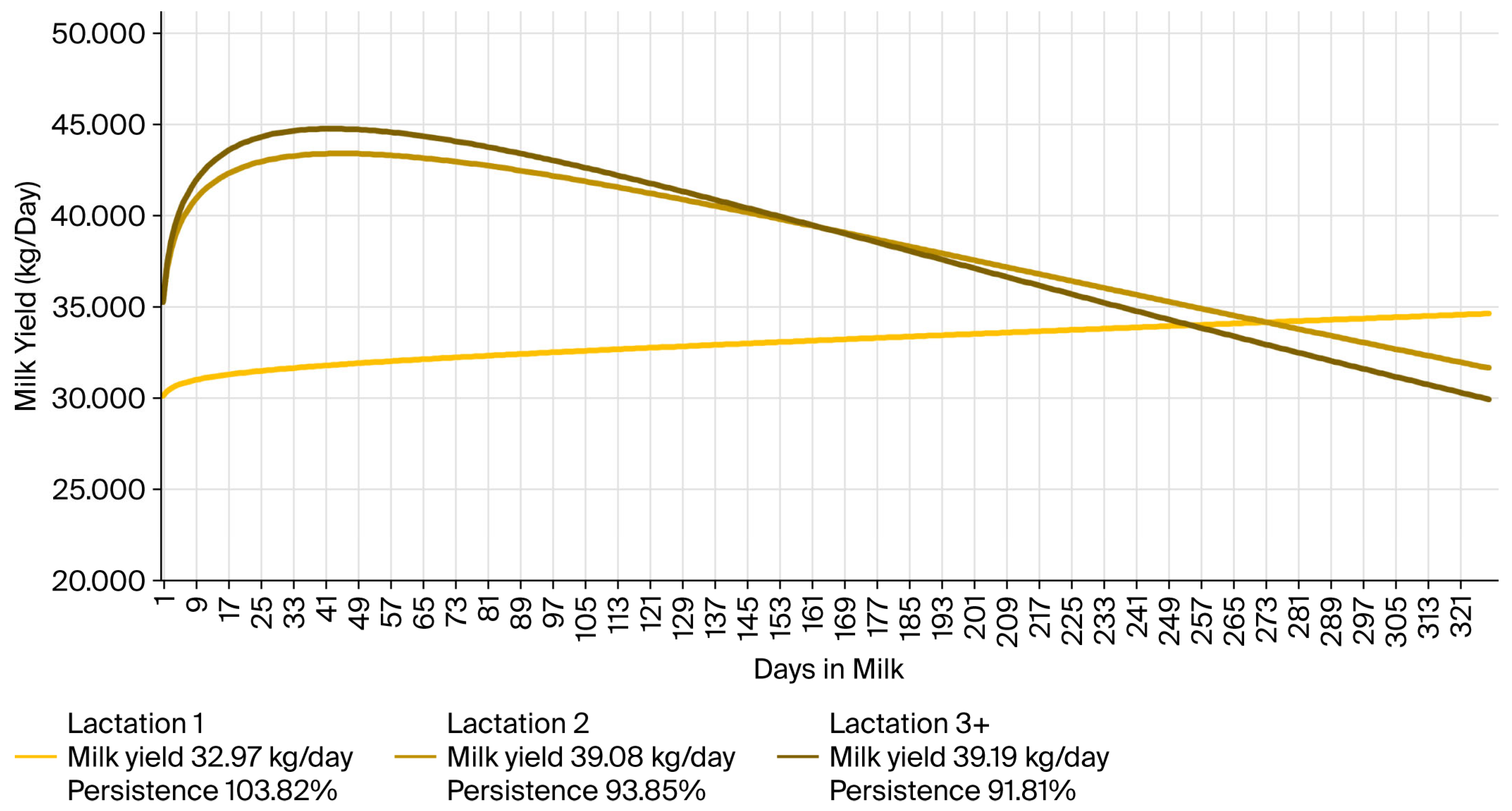

3.1. Overall Phenotype Data and Model Outputs

3.2. Phenotypic Performance in Resilience Indicator Groups

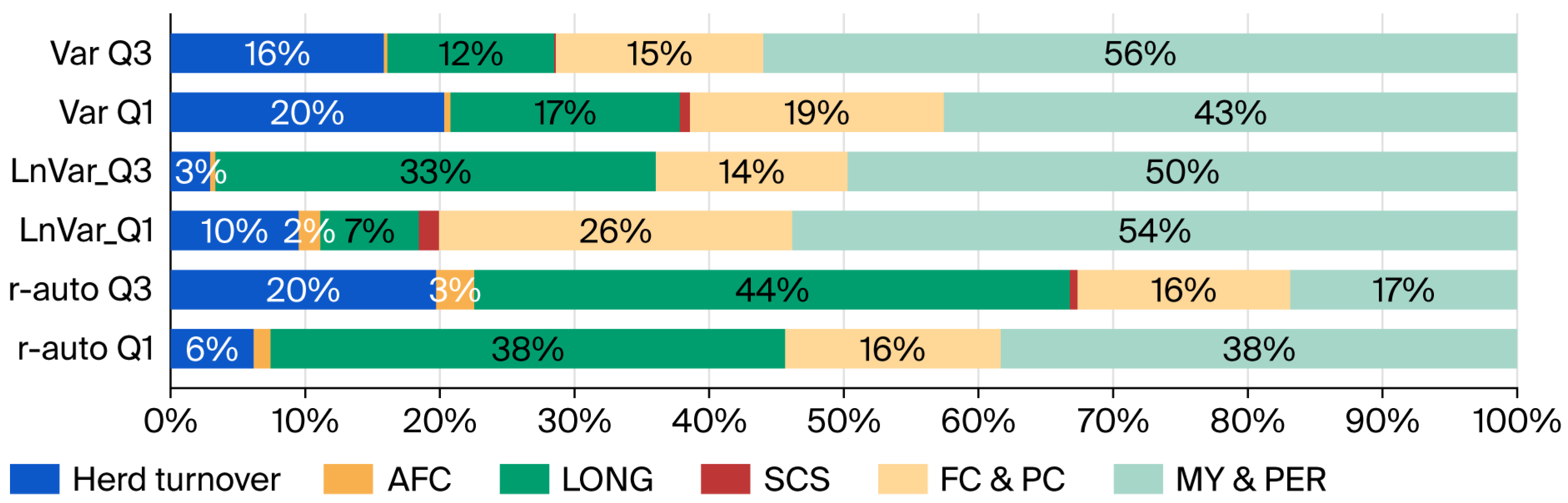

3.3. Resilience Economics on Dairy Farms

4. Discussion

4.1. Phenotypic and Economic Parameters

4.2. Bio-Economic Evaluation of Resilience Indicators

4.2.1. Milk Production

4.2.2. Longevity

4.2.3. SCS, Health, and AFC

4.2.4. Feed Intake and Efficiency

4.2.5. Further System Associations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Colditz, I.G.; Hine, B.C. Resilience in farm animals: Biology, management, breeding and implications for animal welfare. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2016, 56, 1961–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berghof, T.V.L.; Poppe, M.; Mulder, H.A. Opportunities to improve resilience in animal breeding programs. Front. Genet. 2019, 9, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knap, P.W.; Doeschl-Wilson, A. Why breed disease-resilient livestock, and how? Genet. Sel. Evol. 2020, 52, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poppe, M.; Mulder, H.A.; van Pelt, M.L.; Mullaart, E.; Hogeveen, H.; Veerkamp, R.F. Development of resilience indicator traits based on daily step count data for dairy cattle breeding. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2022, 54, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgersma, G.G.; De Jong, G.; Van Der Linde, R.; Mulder, H.A. Fluctuations in Milk Yield Are Heritable and Can Be Used as a Resilience Indicator to Breed Healthy Cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 1240–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheffer, M.; Bolhuis, J.E.; Borsboom, D.; Buchman, T.G.; Gijzel, S.M.W.; Goulson, D.; Kammenga, J.E.; Kemp, B.; van de Leemput, I.A.; Levin, S.; et al. Quantifying resilience of humans and other animals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 11883–11890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oloo, R.D.; Mrode, R.; Bennewitz, J.; Ekine-Dzivenu, C.C.; Ojango, J.M.K.; Gebreyohanes, G.; Mwai, O.A.; Chagunda, M.G.G. Potential for quantifying general environmental resilience of dairy cattle in sub-Saharan Africa using deviations in milk yield. Front. Genet. 2023, 14, 1208158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poppe, M.; Veerkamp, R.F.; Van Pelt, M.L.; Mulder, H.A. Exploration of Variance, Autocorrelation, and Skewness of Deviations from Lactation Curves as Resilience Indicators for Breeding. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 1667–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kašná, E.; Zavadilová, L.; Vařeka, J. Genetic evaluation of resilience indicators in Holstein cows. Animals 2025, 15, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirooka, H. Economic selection index in the genomic era. J. Anim. Breed. Genet. 2019, 136, 151–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, J.; Wolfová, M.; Krupa, E.; Krupová, Z. User’s Manual for the Program Package ECOWEIGHT (C Programs for Calculating Economic Weights in Livestock), version 6.0.5; Part 1: Programs EWBC (version 3.0.3) and EWDC (version 2.2.6) for cattle; Institute of Animal Science: Prague Uhříněves, Czech Republic, 2023; 224p, Available online: https://vuzv.cz/download/users-manual-for-the-program-package-ecoweight-ewbc-ewdc-for-cattle/ (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Krupová, Z.; Kašná, E.; Zavadilová, L.; Krupa, E.; Bauer, J.; Wolfová, M. Udder, claw, and reproductive health in genomic selection of the Czech Holstein. Animals 2024, 14, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krupová, Z.; Zavadilová, L.; Wolfová, M.; Krupa, E.; Kašná, E.; Fleischer, P. Udder and claw-related health traits in selection of Czech Holstein cows. Ann. Anim. Sci. 2019, 19, 647–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seymour, D.J.; Cant, J.P.; Osborne, V.R.; Chud, T.C.S.; Schenkel, F.S.; Miglior, F. A novel method of estimating milking interval-adjusted 24-h milk yields in dairy cattle milked in automated milking systems. Anim. Open Space 2022, 1, 100011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, T.E.; Schaeffer, L.R. Accounting for covariances among test day milk yields in dairy cows. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 1987, 67, 637–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenco, D.; Legarra, A.; Tsuruta, S.; Masuda, Y.; Aguilar, I.; Misztal, I. Single-Step Genomic Evaluations from Theory to Practice: Using SNP Chips and Sequence Data in BLUPF90. Genes 2020, 11, 790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, P.D.P. Algebraic model of the lactation curve in cattle. Nature 1967, 216, 164–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, D.G.; Sniffen, C.J.; O’Connor, J.D.; Russell, J.B.; Van Soest, P.J. The Cornell Net Carbohydrate and Protein System for evaluating cattle diets. Part 1: A model for predicting cattle requirements and feedstuff utilization. Search Agric. 1990, 34, 7–83. [Google Scholar]

- Van Amburgh, M.E.; Collao-Saenz, E.A.; Higgs, R.J.; Ross, D.A.; Recktenwald, E.B.; Raffrenato, E.; Chase, L.E.; Overton, T.R.; Mills, J.K.; Foskolos, A. The Cornell Net Carbohydrate and Protein System: Updates to the model and evaluation of version 6.5. J. Dairy Sci. 2015, 98, 6361–6380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čítek, J.; Brzáková, M.; Hanusová, L.; Hanuš, O.; Večerek, L.; Samková, E.; Jozová, E.; Hoštičková, I.; Trávníček, J.; Klojda, M.; et al. Somatic cell score: Gene polymorphisms and other effects in Holstein and Simmental cows. Anim. Biosci. 2022, 35, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfová, M.; Wolf, J.; Kvapilík, J.; Kica, J. Selection for profit in cattle. I. Economic weights for purebred dairy cattle in the Czech Republic. J. Dairy Sci. 2007, 90, 2442–2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CMBC. Yearbook of Cattle Breeding in the Czech Republic 2024; Czech Moravian Breeders Corporation: Prague, Czech Republic, 2025; 43p, Available online: https://cmsch.sprinx.com/getmedia/1AC39371-FD90-48C8-89B0-373FFFCF78DB/document.aspx (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Radjabalizadeh, K.; Alijani, S.; Gorbani, A.; Farahvash, T. Estimation of genetic parameters of Wood’s lactation curve parameters using Bayesian and REML methods for milk production trait of Holstein dairy cattle. J. Appl. Anim. Res. 2022, 50, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruban, S.; Danshyn, V.; Matvieiev, M.; Borshch, O.O.; Borshch, O.V.; Korol-Bezpala, L. Characteristics of Lactation Curve and Reproduction in Dairy Cattle. Acta Univ. Agric. Silvic. Mendel. Brun. 2023, 70, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Baneh, H.; Gayari, I.; Karunakaran, M.; Venkatesan Raja, T.; Mohan Deb, S.; Mandal, A. Genetic aspects of Wood’s lactation curve parameters in Jersey crossbred cattle using Bayesian approach. J. Dairy Res. 2023, 90, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Steeneveld, W.; Nielen, M.; Hostens, M. Prediction of persistency for day 305 of lactation at the moment of the insemination decision. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1264048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syrůček, J.; Bartoň, L.; Řehák, D.; Štolcová, M.; Burdych, J. Recent development of economic indicators on Czech dairy farms. Agric. Econ.—Czech 2023, 69, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamie, B.A.; Owusu-Sekyere, E.; Lindberg, M.; Agenäs, S.; Nyman, A.-K.; Hansson, H. Dairy cow longevity and farm economic performance: Evidence from Swedish dairy farms. J. Dairy Sci. 2023, 106, 8926–8941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IAEI. Costs and Income of Selected Plant and Animal Products 2023; Institute of Agricultural Economics and Information: Prague, Czech Republic, 2025; 33p, Available online: https://www.uzei.cz/sites/default/files/users/user2/Nakladovost/naklady2023.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Bengtsson, C.; Thomasen, J.R.; Kargo, M.; Bouquet, A.; Slagboom, M. Emphasis on resilience in dairy cattle breeding: Possibilities and consequences. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 105, 7588–7599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, G.R.D.; Valente, J.P.S.; Rezende, V.T.; Araújo, L.F.C.; Silva Neto, J.B.; Mota, L.F.M.; Santana, M.L.; Canesin, R.C.; Bonilha, S.F.M.; Albuquerque, L.G.; et al. Genetic parameters of resilience indicators across growth in beef heifers and their associations with weight, reproduction, calf performance and pre-weaning survival. J. Anim. Breed. Genet. 2025, 143, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Initial Dataset | ||||||||||

| Parameter | N | Mean | SD | Min/Max | ||||||

| DMY (kg per day) | ||||||||||

| Conventional | 278,862 | 38.11 | 9.34 | 2.00/95.40 | ||||||

| AMS | 679,269 | 36.59 | 9.99 | 2.01/93.87 | ||||||

| Robotic parlor | 202,088 | 39.00 | 7.70 | 2.00/78.88 | ||||||

| Total | 1,160,219 | 37.34 | 9.52 | 2.00/95.40 | ||||||

| DIM (days) | 1,160,219 | 148.61 | 87.39 | 0.00/350.00 | ||||||

| Resilience Indicators | ||||||||||

| Data Group | Var | LnVar | r-auto | |||||||

| N | Mean | SD | N | Mean | SD | N | Mean | SD | ||

| Overall dataset | 3655 | 97.68 | 17.34 | 3655 | 97.25 | 16.08 | 3655 | 99.38 | 12.92 | |

| Resilience indicator quartile | Q3 | 911 | 109.34 | 8.20 | 912 | 108.52 | 11.45 | 914 | 108.13 | 13.80 |

| Q2 | 1827 | 97.69 | 17.34 | 1824 | 98.19 | 16.08 | 1826 | 99.61 | 12.92 | |

| Q1 | 917 | 86.43 | 9.20 | 919 | 86.58 | 14.10 | 915 | 91.03 | 15.94 | |

| Data Group | Parameter (Unit) 1 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MY (kg) | FY (kg) | PY (kg) | SCC (ths./mL) | PER (%) | LD (Days) | II (Days) | SP (Days) | CI (Days) | AFC (Days) | CUL (Days) | LONG (Lact.) | |||

| Overall dataset | mean | 11,192 | 410 | 378 | 190 | 97 | 327 | 75 | 107 | 379 | 751 | 1816 | 2.81 | |

| SD | 1971 | 47.80 | 43.54 | 14.40 | 12.19 | 67.76 | 19.99 | 42.19 | 46.66 | 93.74 | 622.14 | 1.42 | ||

| Var | Q3 | mean | 10,740 | 403 | 370 | 174 | 98 | 334 | 75 | 108 | 379 | 753 | 1860 | 2.91 |

| SD | 2174 | 48.49 | 43.67 | 14.33 | 9.75 | 70.88 | 19.27 | 42.47 | 44.18 | 96.61 | 647.14 | 1.47 | ||

| Q2 | mean | 11,261 | 412 | 380 | 186 | 97 | 328 | 75 | 107 | 380 | 752 | 1775 | 2.72 | |

| SD | 2204 | 47.80 | 43.35 | 14.38 | 11.67 | 66.13 | 19.06 | 42.02 | 48.52 | 94.62 | 628.56 | 1.44 | ||

| Q1 | mean | 11,504 | 413 | 381 | 214 | 98 | 320 | 76 | 104 | 378 | 748 | 1763 | 2.66 | |

| SD | 2254 | 46.90 | 43.49 | 14.49 | 15.11 | 67.17 | 22.38 | 42.24 | 45.21 | 89.00 | 539.13 | 1.27 | ||

| LnVar | Q3 | mean | 10,783 | 403 | 372 | 173 | 96 | 331 | 75 | 108 | 382 | 757 | 1910 | 3.02 |

| SD | 2119 | 47.37 | 42.15 | 14.33 | 11.19 | 65.64 | 20.01 | 43.14 | 45.72 | 97.92 | 623.36 | 1.49 | ||

| Q2 | mean | 11,225 | 411 | 379 | 184 | 98 | 328 | 75 | 106 | 379 | 752 | 1844 | 2.88 | |

| SD | 2221 | 48.25 | 44.05 | 14.38 | 12.06 | 67.53 | 19.06 | 41.51 | 47.68 | 95.40 | 631.57 | 1.44 | ||

| Q1 | mean | 11,533 | 415 | 381 | 219 | 97 | 324 | 75 | 106 | 377 | 745 | 1689 | 2.50 | |

| SD | 2278 | 47.13 | 43.74 | 14.51 | 13.33 | 70.13 | 21.72 | 42.59 | 45.68 | 85.50 | 583.32 | 1.30 | ||

| r-auto | Q3 | mean | 11,048 | 410 | 377 | 165 | 98 | 327 | 75 | 105 | 375 | 755 | 1739 | 2.63 |

| SD | 2303 | 51.01 | 45.40 | 14.30 | 11.54 | 65.92 | 19.04 | 42.01 | 42.43 | 93.90 | 562.37 | 1.29 | ||

| Q2 | mean | 11,191 | 410 | 378 | 199 | 97 | 329 | 76 | 108 | 382 | 752 | 1868 | 2.92 | |

| SD | 2187 | 46.14 | 42.88 | 14.43 | 12.27 | 69.46 | 20.92 | 42.55 | 47.60 | 95.33 | 651.31 | 1.50 | ||

| Q1 | mean | 11,337 | 411 | 378 | 196 | 97 | 325 | 75 | 105 | 378 | 746 | 1776 | 2.72 | |

| SD | 2219 | 47.80 | 42.99 | 14.42 | 12.65 | 66.08 | 19.01 | 41.65 | 48.30 | 90.12 | 603.65 | 1.37 | ||

| Data Group | Parameter of Lactation Curve/Lactation | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | b | c | |||||||

| 1 | 2+ | 1 | 2 | 3+ | 1 | 2 | 3+ | ||

| Overall dataset | 30.108 | 35.323 | 0.01225 | 0.07340 | 0.08610 | 0.000210 | −0.001631 | −0.002025 | |

| Var | Q3 | 28.858 | 34.073 | 0.01200 | 0.06782 | 0.07320 | 0.000072 | −0.001389 | −0.001650 |

| Q2 | 30.142 | 35.357 | 0.01230 | 0.08080 | 0.08910 | 0.000183 | −0.001771 | −0.002081 | |

| Q1 | 30.378 | 35.593 | 0.02110 | 0.07725 | 0.10149 | 0.000265 | −0.001806 | −0.002401 | |

| LnVar | Q3 | 28.858 | 34.073 | 0.01059 | 0.07150 | 0.09132 | 0.000160 | −0.001688 | −0.002140 |

| Q2 | 30.108 | 35.323 | 0.00815 | 0.07780 | 0.08490 | 0.000312 | −0.001678 | −0.001955 | |

| Q1 | 30.885 | 36.100 | 0.01900 | 0.07070 | 0.09118 | 0.000092 | −0.001541 | −0.002160 | |

| r-auto | Q3 | 29.466 | 34.681 | 0.00480 | 0.08040 | 0.08715 | 0.000402 | −0.001705 | −0.001944 |

| Q2 | 30.074 | 35.289 | 0.00950 | 0.07552 | 0.08732 | 0.000278 | −0.001688 | −0.002085 | |

| Q1 | 30.176 | 35.391 | 0.03290 | 0.06969 | 0.08950 | −0.000219 | −0.001553 | −0.002065 | |

| Data Group | Parameter (Unit) 1 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fat Content (FC; %) | Protein Content (PC; %) | Somatic Cell Score (SCS; Score) | Days in Dry (Day) | Pregnancy Length (Day) | |||

| Overall dataset | mean | 3.69 | 3.39 | 3.92 | 52 | 273 | |

| SD | 0.224 | 0.090 | 0.204 | 10.76 | 33.55 | ||

| Var | Q3 | mean | 3.78 | 3.45 | 3.80 | 45 | 272 |

| SD | 0.229 | 0.092 | 0.197 | 9.66 | 31.65 | ||

| Q2 | mean | 3.69 | 3.38 | 3.89 | 52 | 273 | |

| SD | 0.223 | 0.090 | 0.202 | 10.58 | 34.85 | ||

| Q1 | mean | 3.62 | 3.32 | 4.09 | 58 | 273 | |

| SD | 0.219 | 0.089 | 0.213 | 12.10 | 32.72 | ||

| LnVar | Q3 | mean | 3.76 | 3.46 | 3.79 | 51 | 274 |

| SD | 0.228 | 0.092 | 0.197 | 10.11 | 32.83 | ||

| Q2 | mean | 3.69 | 3.38 | 3.88 | 52 | 273 | |

| SD | 0.224 | 0.090 | 0.202 | 10.67 | 34.32 | ||

| Q1 | mean | 3.62 | 3.31 | 4.13 | 54 | 271 | |

| SD | 0.219 | 0.0885 | 0.215 | 11.63 | 32.83 | ||

| r-auto | Q3 | mean | 3.73 | 3.42 | 3.72 | 48 | 270 |

| SD | 0.226 | 0.091 | 0.194 | 9.73 | 30.52 | ||

| Q2 | mean | 3.69 | 3.39 | 3.99 | 53 | 274 | |

| SD | 0.224 | 0.090 | 0.207 | 11.22 | 34.16 | ||

| Q1 | mean | 3.65 | 3.35 | 3.97 | 54 | 273 | |

| SD | 0.221 | 0.089 | 0.206 | 10.89 | 34.85 | ||

| Data Group | MY (kg) | FY (kg) | FC (%) | PY (kg) | PC (%) | SCS (Score) | PER (%) | LD (Days) | II (Days) | SP (Days) | CI (Days) | AFC (Days) | CUL (Days) | LONG (Lact.) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Var | Q1:Q2 | 0.001 | 0.992 | 0.001 | 0.872 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.950 | 0.009 | 0.035 | 0.495 | 0.512 | 0.890 | 0.313 | 0.281 |

| Q2:Q3 | 0.001 | 0.044 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.134 | 0.025 | 0.505 | 0.447 | 0.994 | 0.899 | 0.014 | 0.002 | |

| Q1:Q3 | 0.001 | 0.094 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.307 | 0.001 | 0.020 | 0.851 | 0.571 | 0.818 | 0.170 | 0.060 | |

| LnVar | Q1:Q2 | 0.001 | 0.624 | 0.001 | 0.790 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.230 | 0.223 | 0.045 | 0.459 | 0.968 | 0.317 | 0.038 | 0.011 |

| Q2:Q3 | 0.001 | 0.010 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.022 | 0.022 | 0.292 | 0.720 | 0.787 | 0.396 | 0.180 | 0.481 | |

| Q1:Q3 | 0.001 | 0.010 | 0.001 | 0.005 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.501 | 0.501 | 0.010 | 0.729 | 0.836 | 0.921 | 0.004 | 0.007 | |

| r-auto | Q1:Q2 | 0.203 | 0.702 | 0.002 | 0.503 | 0.001 | 0.008 | 0.023 | 0.009 | 0.035 | 0.495 | 0.512 | 0.553 | 0.313 | 0.281 |

| Q2:Q3 | 0.047 | 0.642 | 0.039 | 0.887 | 0.001 | 0.010 | 0.584 | 0.025 | 0.505 | 0.851 | 0.994 | 0.030 | 0.014 | 0.002 | |

| Q1:Q3 | 0.005 | 0.355 | 0.001 | 0.408 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.014 | 0.001 | 0.020 | 0.447 | 0.571 | 0.164 | 0.170 | 0.060 | |

| Data Group 1 | Economic Parameters | Difference 2 from the Respective Resilience Q2 Group (Overall Dataset) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Revenues | Costs | Profit | Profitability | Revenues | Costs | Profit | Profitability | |||||

| EUR per Cow and per Year | % | EUR | (%) | EUR | (%) | EUR | (%) | p.p. | ||||

| Overall dataset | 4643 | 4507 | 136 | 3.0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Var | Q3 | 4641 | 4526 | 115 | 2.5 | −28 (−2) | −1 (0) | 10 (19) | 0 (0) | −38 (−21) | −25 (−15) | −0.9 (−0.5) |

| Q2 | 4669 | 4516 | 153 | 3.4 | (26) | (1) | (8) | (0) | (18) | (13) | (0.4) | |

| Q1 | 4626 | 4498 | 128 | 2.9 | −43 (−17) | −1 (0) | −18 (−10) | 0 (0) | −25 (−7) | −16 (−5) | −0.5 (−0.2) | |

| LnVar | Q3 | 4673 | 4546 | 128 | 2.8 | 40 (30) | 1 (1) | 44 (38) | 1 (1) | −4 (−8) | −3 (−6) | −0.1 (−0.2) |

| Q2 | 4633 | 4502 | 132 | 2.9 | (−10) | (0) | (−6) | (0) | (−4) | (−3) | (−0.1) | |

| Q1 | 4649 | 4502 | 146 | 3.3 | 15 (6) | 0 (0) | 1 (−5) | 0 (0) | 15 (11) | 11 (8) | 0.3 (0.2) | |

| r-auto | Q3 | 4623 | 4508 | 115 | 2.6 | −54 (−20) | −1 (0) | −16 (1) | 0 (0) | −37 (−20) | −25 (−15) | −0.8 (−0.5) |

| Q2 | 4677 | 4524 | 153 | 3.4 | (34) | (1) | (17) | (0) | (17) | (13) | (0.4) | |

| Q1 | 4612 | 4490 | 122 | 2.7 | −64 (−30) | −1 (−1) | −34 (−17) | −1 (0) | −30 (−13) | −20 (−10) | −0.6 (−0.3) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Krupová, Z.; Kašná, E.; Zavadilová, L.; Krupa, E. A Bio-Economic Evaluation of Var, LnVar, and r-Auto Resilience Indicators in Czech Holstein Cattle. Animals 2025, 15, 3593. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243593

Krupová Z, Kašná E, Zavadilová L, Krupa E. A Bio-Economic Evaluation of Var, LnVar, and r-Auto Resilience Indicators in Czech Holstein Cattle. Animals. 2025; 15(24):3593. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243593

Chicago/Turabian StyleKrupová, Zuzana, Eva Kašná, Ludmila Zavadilová, and Emil Krupa. 2025. "A Bio-Economic Evaluation of Var, LnVar, and r-Auto Resilience Indicators in Czech Holstein Cattle" Animals 15, no. 24: 3593. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243593

APA StyleKrupová, Z., Kašná, E., Zavadilová, L., & Krupa, E. (2025). A Bio-Economic Evaluation of Var, LnVar, and r-Auto Resilience Indicators in Czech Holstein Cattle. Animals, 15(24), 3593. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243593