Multipurpose Passive Surveillance of Bat-Borne Viruses in Hungary: Lyssaviruses and Filoviruses in Focus

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Samples

2.2. Bat Necropsy

2.3. Nucleic Acid Extraction and PCR Reactions

2.4. Viral Enrichment and RNA Extraction

2.5. Illumina Sequencing

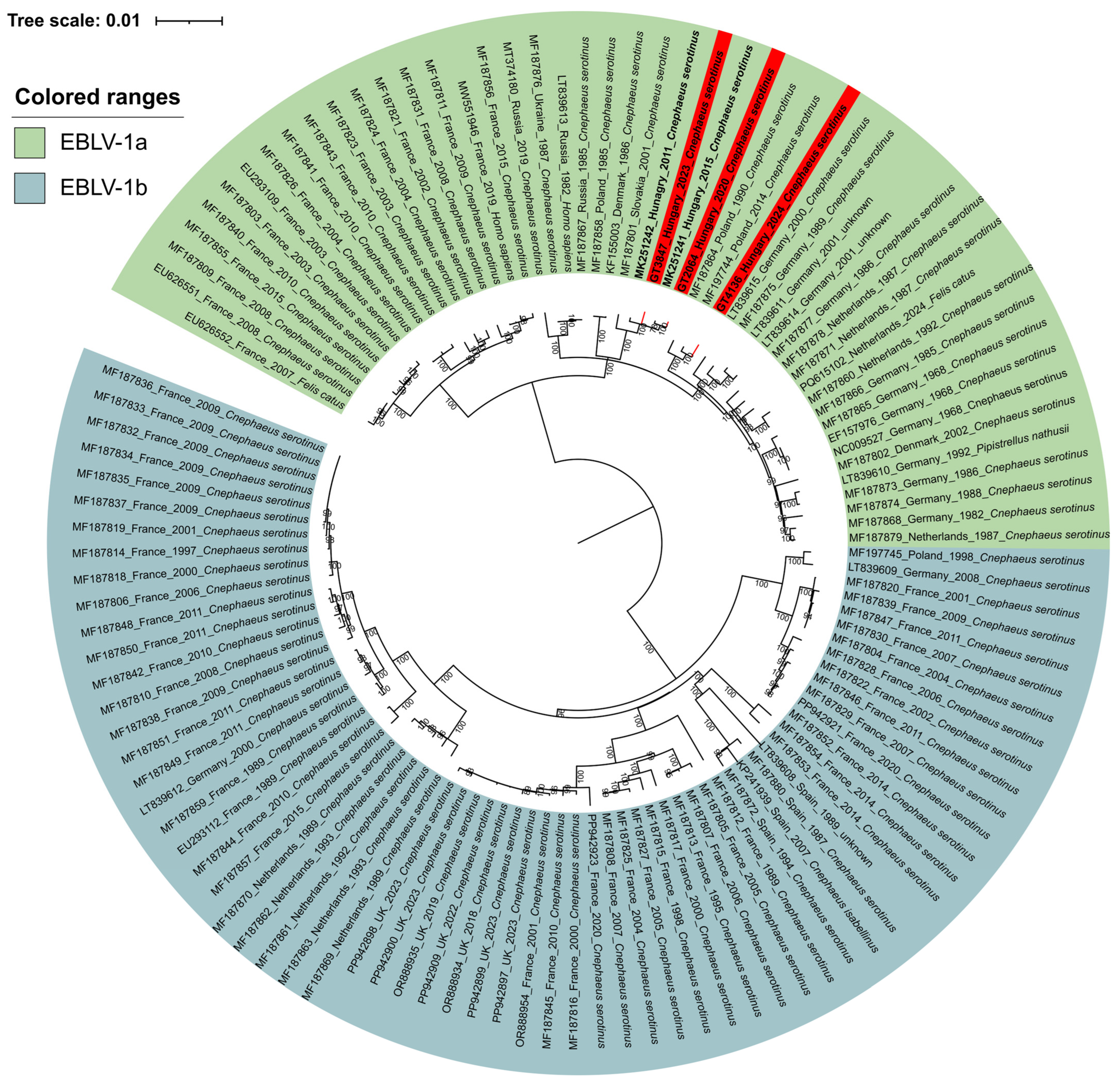

2.6. Phylogenetic Analysis

3. Results

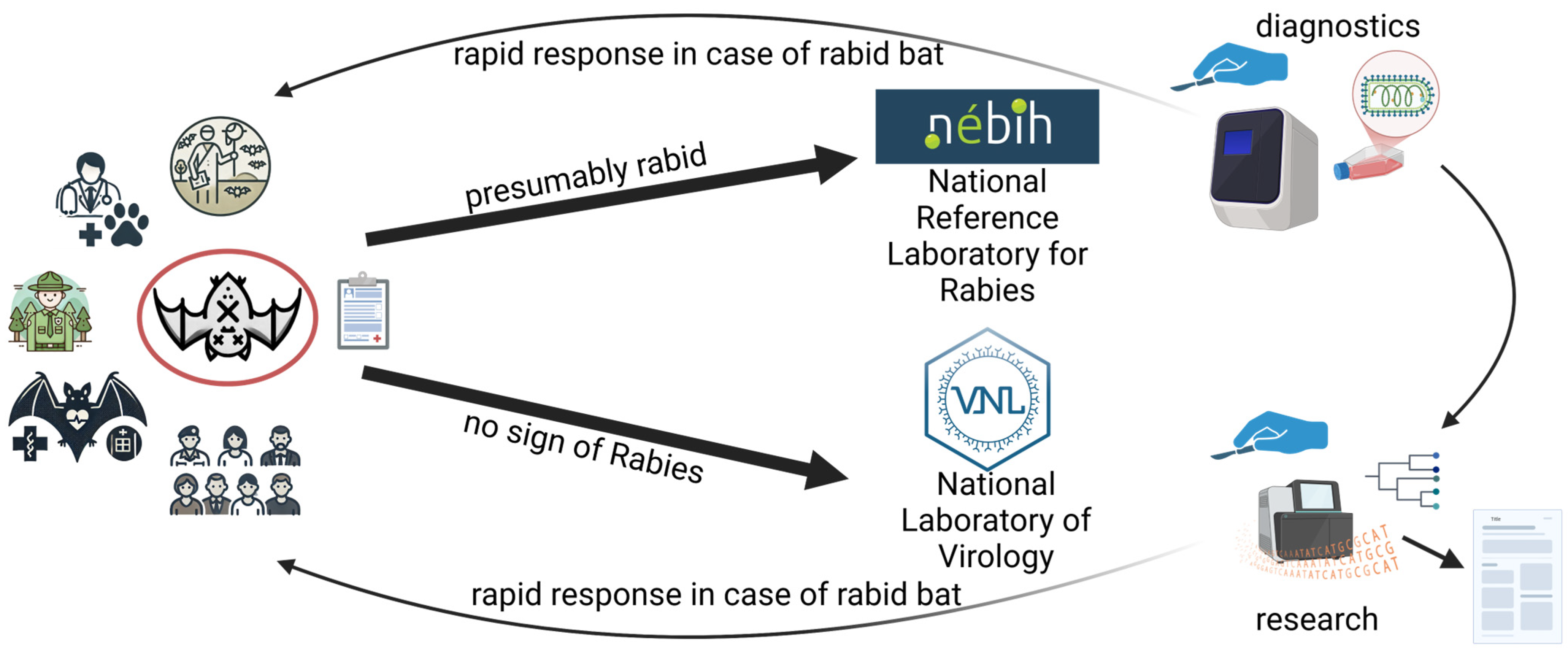

3.1. A Passive Surveillance System to Detect Bat-Borne Viruses

3.2. Lyssavirus Survey

3.3. Surveillance Data on EBLV-1a Positive Bats

3.4. Lloviu Virus Survey

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABLV | Lyssavirus australis |

| ARAV | Lyssavirus aravan |

| BBLV | Lyssavirus bokeloh |

| cDNA | Complementary Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| DUVV | Lyssavirus duvenhage |

| EBLV | European bat lyssavirus |

| EBLV-1 | Lyssavirus hamburg |

| EBLV-1a | European bat lyssavirus 1a strain |

| EBLV-2 | Lyssavirus helsinki |

| GBLV | Lyssavirus gannoruwa |

| ICTV | International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses |

| IKOV | Lyssavirus ikoma |

| IRKV | Lyssavirus irkut |

| KBLV | Lyssavirus kotalahti |

| KHUV | Lyssavirus khujand |

| LBV | Lyssavirus lagos |

| LLEBV | Lyssavirus lleida |

| LLOV | Cuevavirus lloviuense |

| MOKV | Lyssavirus mokola |

| N gene | Nucleoprotein gene |

| NCBI | National Center for Biotechnology Information |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered Saline |

| Pan-Lyssa RT-nPCR | Pan-Lyssavirus reverse transcription nested polimerase chain reaction |

| RABV | Lyssavirus rabies |

| RNA | Ribonucleic Acid |

| SHIBV | Lyssavirus shimoni |

| TWBLV | Lyssavirus formosa |

| UK | United Kingdom |

| WCBV | Lyssavirus caucasicus |

References

- Pfenning-Butterworth, A.; Buckley, L.B.; Drake, J.M.; Farner, J.E.; Farrell, M.J.; Gehman, A.M.; Mordecai, E.A.; Stephens, P.R.; Gittleman, J.L.; Davies, T.J. Interconnecting global threats: Climate change, biodiversity loss, and infectious diseases. Lancet Planet Health 2024, 8, e270–e283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- One Health High-Level Expert Panel (OHHLEP); Hayman, D.T.S.; Adisasmito, W.B.; Almuhairi, S.; Behravesh, C.B.; Bilivogui, P.; Bukachi, S.A.; Casas, N.; Becerra, N.C.; Charron, D.F.; et al. Developing One Health surveillance systems. One Health 2023, 17, 100617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- One Health High-Level Expert Panel (OHHLEP); Markotter, W.; Mettenleiter, T.C.; Adisasmito, W.B.; Almuhairi, S.; Barton Behravesh, C.; Bilivogui, P.; Bukachi, S.A.; Casas, N.; Cediel Becerra, N.; et al. Prevention of zoonotic spillover: From relying on response to reducing the risk at source. PLoS Pathog. 2023, 19, e1011504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irving, A.T.; Ahn, M.; Goh, G.; Anderson, D.E.; Wang, L.F. Lessons from the host defences of bats, a unique viral reservoir. Nature 2021, 589, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seal, S.; Dharmarajan, G.; Khan, I. Evolution of pathogen tolerance and emerging infections: A missing experimental paradigm. eLife 2021, 10, e68874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latinne, A.; Nga, N.T.T.; Long, N.V.; Ngoc, P.T.B.; Thuy, H.B.; Predict Consortium; Long, N.V.; Long, P.T.; Phuong, N.T.; Quang, L.T.V.; et al. One Health Surveillance Highlights Circulation of Viruses with Zoonotic Potential in Bats, Pigs, and Humans in Viet Nam. Viruses 2023, 15, 790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubareka, S.; Amuasi, J.; Banerjee, A.; Carabin, H.; Copper Jack, J.; Jardine, C.; Jaroszewicz, B.; Keefe, G.; Kotwa, J.; Kutz, S.; et al. Strengthening a One Health approach to emerging zoonoses. Facets 2023, 8, 1–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, V.; Hurtado-Monzón, A.M.; O’Krafka, S.; Mühlberger, E.; Letko, M.; Frank, H.K.; Laing, E.D.; Phelps, K.L.; Becker, D.J.; Munster, V.J.; et al. Studying bats using a One Health lens: Bridging the gap between bat virology and disease ecology. J. Virol. 2024, 98, e0145324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, S.L.; Brookes, S.M.; Jones, G.; Hutson, A.M.; Racey, P.A.; Aegerter, J.; Smith, G.C.; McElhinney, L.M.; Fooks, A.R. European bat lyssaviruses: Distribution, prevalence and implications for conservation. Biol. Conserv. 2006, 131, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.C.; Hsu, C.L.; Lee, M.S.; Tu, Y.C.; Chang, J.C.; Wu, C.H.; Lee, S.H.; Ting, L.J.; Tsai, K.R.; Cheng, M.C.; et al. Lyssavirus in Japanese Pipistrelle, Taiwan. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2018, 24, 782–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badrane, H.; Bahloul, C.; Perrin, P.; Tordo, N. Evidence of two Lyssavirus phylogroups with distinct pathogenicity and immunogenicity. J. Virol. 2001, 75, 3268–3276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, J.F.; Moore, G.J. Susceptibility of carnivora to rabies virus administered orally. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1971, 93, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, C.R.; Streicker, D.G.; Schnell, M.J. The spread and evolution of rabies virus: Conquering new frontiers. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramsden, R.O.; Johnston, D.H. Studies on the oral infectivity of rabies virus in carnivora. J. Wildl. Dis. 1975, 11, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Hamed, S.; Myers, J.F.; Chandwani, A.; Wirblich, C.; Kurup, D.; Paran, N.; Schnell, M.J. Toward the Development of a Pan-Lyssavirus Vaccine. Viruses 2024, 16, 1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, C.R.; Lowe, D.E.; Smith, T.G.; Yang, Y.; Hutson, C.L.; Wirblich, C.; Cingolani, G.; Schnell, M.J. Lyssavirus Vaccine with a Chimeric Glycoprotein Protects across Phylogroups. Cell Rep. 2020, 32, 107920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Expert Consultation on Rabies, Third Report; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Mohr, W. Die Tollwut [Rabies]. Med. Klin. 1957, 52, 1057–1060. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Jelesic, Z.; Nikolic, M. Isolation of rabies virus from insectivorous bats in Yugoslavia. Bull. World Health Organ. 1956, 14, 801–804. [Google Scholar]

- Schatz, J.; Fooks, A.R.; McElhinney, L.; Horton, D.; Echevarria, J.; Vázquez-Moron, S.; Kooi, E.A.; Rasmussen, T.B.; Müller, T.; Freuling, C.M. Bat rabies surveillance in Europe. Zoonoses Public Health 2013, 60, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freuling, C.M.; Beer, M.; Conraths, F.J.; Finke, S.; Hoffmann, B.; Keller, B.; Kliemt, J.; Mettenleiter, T.C.; Mühlbach, E.; Teifke, J.P.; et al. Novel lyssavirus in Natterer’s bat, Germany. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2011, 17, 1519–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leopardi, S.; Dacheux, L.; Serra-Cobo, J.; Ábrahám, Á.; Bajić, B.; Bourhy, H.; Bücs, S.L.; Budinski, I.; Castellan, M.; Drzewniokova, P.; et al. European distribution and intramuscular pathogenicity of divergent lyssaviruses West Caucasian bat virus and Lleida bat lyssavirus. iScience 2025, 28, 111738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dundarova, H.; Ivanova-Aleksandrova, N.; Bednarikova, S.; Georgieva, I.; Kirov, K.; Miteva, K.; Neov, B.; Ostoich, P.; Pikula, J.; Zukal, J.; et al. Phylogeographic Aspects of Bat Lyssaviruses in Europe: A Review. Pathogens 2023, 12, 1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, A.; Calvelage, S.; Schlottau, K.; Hoffmann, B.; Eggerbauer, E.; Müller, T.; Freuling, C.M. Retrospective Enhanced Bat Lyssavirus Surveillance in Germany between 2018–2020. Viruses 2021, 13, 1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohl, C.; Nitsche, A.; Kurth, A. Update on Potentially Zoonotic Viruses of European Bats. Vaccines 2021, 9, 690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golding, M.E.; Wu, G.; Wilkie, R.; Picard-Meyer, E.; Servat, A.; Marston, D.A.; Aegerter, J.N.; Horton, D.L.; McElhinney, L.M. Investigating the emergence of a zoonotic virus: Phylogenetic analysis of European bat lyssavirus 1 in the UK. Virus Evol. 2024, 10, veae060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Poel, W.H.; Lina, P.H.; Kramps, J.A. Public health awareness of emerging zoonotic viruses of bats: A European perspective. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2006, 6, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negredo, A.; Palacios, G.; Vázquez-Morón, S.; González, F.; Dopazo, H.; Molero, F.; Juste, J.; Quetglas, J.; Savji, N.; de la Cruz Martínez, M.; et al. Discovery of an Ebolavirus-like Filovirus in Europe. PLoS Pathog. 2011, 7, e1002304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemenesi, G.; Kurucz, K.; Dallos, B.; Zana, B.; Földes, F.; Boldogh, S.; Görföl, T.; Carroll, M.W.; Jakab, F. Re-emergence of Lloviu virus in Miniopterus schreibersii bats, Hungary, 2016. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2018, 7, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóth, G.E.; Hume, A.J.; Suder, E.L.; Zeghbib, S.; Ábrahám, Á.; Lanszki, Z.; Varga, Z.; Tauber, Z.; Földes, F.; Zana, B.; et al. Isolation and genome characterization of Lloviu virus from Italian Schreibers’s bats. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 11310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goletic, S.; Goletic, T.; Omeragic, J.; Supic, J.; Kapo, N.; Nicevic, M.; Skapur, V.; Rukavina, D.; Maksimovic, Z.; Softic, A.; et al. Metagenomic sequencing of Lloviu virus from dead Schreiber’s bats in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forró, B.; Marton, S.; Fehér, E.; Domán, M.; Kemenesi, G.; Cadar, D.; Hornyák, Á.; Bányai, K. Phylogeny of Hungarian EBLV-1 strains using whole-genome sequence data. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2021, 68, 1323–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidovszky, M.Z.; Boldogh, S. Detection of adenoviruses in the Northern Hungarian bat fauna. Magy. Állatorvosok Lapja 2011, 133, 747–753. [Google Scholar]

- Kemenesi, G.; Dallos, B.; Görföl, T.; Boldogh, S.; Estók, P.; Kurucz, K.; Kutas, A.; Földes, F.; Oldal, M.; Németh, V.; et al. Molecular survey of RNA viruses in Hungarian bats: Discovering novel astroviruses, coronaviruses, and caliciviruses. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2014, 14, 846–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemenesi, G.; Zhang, D.; Marton, S.; Dallos, B.; Görföl, T.; Estók, P.; Boldogh, S.; Kurucz, K.; Oldal, M.; Kutas, A.; et al. Genetic characterization of a novel picornavirus detected in Miniopterus schreibersii bats. J. Gen. Virol. 2015, 96, 815–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Vargas, F.; Solorzano-Scott, T.; Baldi, M.; Barquero-Calvo, E.; Jiménez-Rocha, A.; Jiménez, C.; Piche-Ovares, M.; Dolz, G.; León, B.; Corrales-Aguilar, E.; et al. Passive epidemiological surveillance in wildlife in Costa Rica identifies pathogens of zoonotic and conservation importance. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fooks, A.R.; Brookes, S.M.; Johnson, N.; McElhinney, L.M.; Hutson, A.M. European bat lyssaviruses: An emerging zoonosis. Epidemiol. Infect. 2003, 131, 1029–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speare, R.; Luly, J.; Reimers, J.; Durrheim, D.; Lunt, R. Antibodies to Australian bat lyssavirus in an asymptomatic bat carer. Intern. Med. J. 2013, 43, 1256–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schatz, J.; Freuling, C.M.; Auer, E.; Goharriz, H.; Harbusch, C.; Johnson, N.; Kaipf, I.; Mettenleiter, T.C.; Mühldorfer, K.; Mühle, R.U.; et al. Enhanced passive bat rabies surveillance in indigenous bat species from Germany—A retrospective study. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2014, 8, e2835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picard-Meyer, E.; Servat, A.; Wasniewski, M.; Gaillard, M.; Borel, C.; Cliquet, F. Bat rabies surveillance in France: First report of unusual mortality among serotine bats. BMC Vet. Res. 2017, 13, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, S.L.; Brookes, S.M.; Jones, G.; Hutson, A.M.; Fooks, A.R. Passive surveillance (1987 to 2004) of United Kingdom bats for European bat lyssaviruses. Vet. Rec. 2006, 159, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eblé, P.; Dekker, A.; van den End, S.; Visser, V.; Engelsma, M.; Harders, F.; van Keulen, L.; van Weezep, E.; Holwerda, M. A case report of a cat infected with European bat lyssavirus type 1, the Netherlands, October 2024. Euro Surveill. 2025, 30, 2500154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, N.B.; Cirranello, A.L. Bat Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Database, version 1.9. 2025. Available online: https://batnames.org/ (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Vázquez-Morón, S.; Avellón, A.; Echevarría, J.E. RT-PCR for detection of all seven genotypes of Lyssavirus genus. J. Virol. Methods 2006, 135, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conceição-Neto, N.; Zeller, M.; Lefrère, H.; De Bruyn, P.; Beller, L.; Deboutte, W.; Yinda, C.K.; Lavigne, R.; Maes, P.; Van Ranst, M.; et al. Modular approach to customise sample preparation procedures for viral metagenomics: A reproducible protocol for virome analysis. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 16532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minh, B.Q.; Schmidt, H.A.; Chernomor, O.; Schrempf, D.; Woodhams, M.D.; von Haeseler, A.; Lanfear, R. IQ-TREE 2: New Models and Efficient Methods for Phylogenetic Inference in the Genomic Era. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2020, 37, 1530–1534, Erratum in Mol. Biol. Evol. 2020, 37, 2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v6: Recent updates to the phylogenetic tree display and annotation tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, W78–W82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wise, E.L.; Marston, D.A.; Banyard, A.C.; Goharriz, H.; Selden, D.; Maclaren, N.; Goddard, T.; Johnson, N.; McElhinney, L.M.; Brouwer, A.; et al. Passive surveillance of United Kingdom bats for lyssaviruses (2005–2015). Epidemiol. Infect. 2017, 145, 2445–2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leopardi, S.; Priori, P.; Zecchin, B.; Poglayen, G.; Trevisiol, K.; Lelli, D.; Zoppi, S.; Scicluna, M.T.; D’Avino, N.; Schiavon, E.; et al. Active and passive surveillance for bat lyssaviruses in Italy revealed serological evidence for their circulation in three bat species. Epidemiol. Infect. 2018, 147, e63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, R.; Stentiford, G.D.; Walker, D.I.; Baker-Austin, C.; Ward, G.; Maskrey, B.H.; van Aerle, R.; Verner-Jeffreys, D.; Peeler, E.; Bass, D. Realising a global One Health disease surveillance approach: Insights from wastewater and beyond. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 5324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacFarlane, D.; Rocha, R. Guidelines for communicating about bats to prevent persecution in the time of COVID-19. Biol. Conserv. 2020, 248, 108650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gucht, S.; Verlinde, R.; Colyn, J.; Vanderpas, J.; Vanhoof, R.; Roels, S.; Francart, A.; Brochier, B.; Suin, V. Favourable outcome in a patient bitten by a rabid bat infected with the European bat lyssavirus-1. Acta Clin. Belg. 2013, 68, 54–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smreczak, M.; Orłowska, A.; Marzec, A.; Trębas, P.; Müller, T.; Freuling, C.M.; Żmudziński, J.F. Bokeloh bat lyssavirus isolation in a Natterer’s bat, Poland. Zoonoses Public Health 2018, 65, 1015–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schatz, J.; Ohlendorf, B.; Busse, P.; Pelz, G.; Dolch, D.; Teubner, J.; Encarnação, J.A.; Mühle, R.-U.; Fischer, M.; Hoffmann, B.; et al. Twenty years of active bat rabies surveillance in Germany: A detailed analysis and future perspectives. Epidemiol. Infect. 2014, 142, 1155–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regnault, B.; Evrard, B.; Plu, I.; Dacheux, L.; Troadec, E.; Cozette, P.; Chrétien, D.; Duchesne, M.; Vallat, J.M.; Jamet, A.; et al. First Case of Lethal Encephalitis in Western Europe Due to European Bat Lyssavirus Type 1. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 74, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schatz, J.; Teifke, J.P.; Mettenleiter, T.C.; Aue, A.; Stiefel, D.; Müller, T.; Freuling, C.M. Lyssavirus distribution in naturally infected bats from Germany. Vet. Microbiol. 2014, 169, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemenesi, G.; Tóth, G.E.; Mayora-Neto, M.; Scott, S.; Temperton, N.; Wright, E.; Mühlberger, E.; Hume, A.J.; Suder, E.L.; Zana, B.; et al. Isolation of infectious Lloviu virus from Schreiber’s bats in Hungary. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parize, P.; Travecedo Robledo, I.C.; Cervantes-Gonzalez, M.; Kergoat, L.; Larrous, F.; Serra-Cobo, J.; Dacheux, L.; Bourhy, H. Circumstances of Human-Bat interactions and risk of lyssavirus transmission in metropolitan France. Zoonoses Public Health 2020, 67, 774–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vodopija, R.; Lojkić, I.; Hamidović, D.; Boneta, J.; Primorac, D. Bat Bites and Rabies PEP in the Croatian Reference Centre for Rabies 1995–2020. Viruses 2024, 16, 876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Species | Cser | Hsav | Mdau | Mmyo | Mmys | Mnat | Nlei | Nnoc | Pkuh | Pnat | Ppip | Paur | Paus | Rhip | Vmur | ∑ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year/Habitat | U | U | U/R | U/R | R | R | R | U (R) | U | R (U) | R (U) | R | U | U | U | |

| 2018 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2 |

| 2019 | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 3 |

| 2020 | 1/1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | - | - | - | 3 | 2 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 13 |

| 2021 | 2 | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | 21 | 12 | - | 1 | - | 2 | - | 4 | 43 |

| 2022 | 6 | 5 | 1 | - | - | - | - | 7 | 59 | 1 | - | - | 3 | 1 | 1 | 84 |

| 2023 | 7/1 | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | 6 | 12 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | 31 |

| 2024 | 1/1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 3 |

| 2018–2024 (no specific date) | 9 | 3 | 1 | - | - | - | - | 5 | 7 | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | 29 |

| ∑ | 26/3 | 12 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 43 | 94 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 7 | 1 | 6 | 208 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Szabó, A.; Lanszki, Z.; Kemenesi, G.; Nándori, A.; Malik, P.; Bányai, K.; Károlyi, H.F.; Nagy, Á.; Sós, E.; Banović, P.; et al. Multipurpose Passive Surveillance of Bat-Borne Viruses in Hungary: Lyssaviruses and Filoviruses in Focus. Animals 2025, 15, 3590. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243590

Szabó A, Lanszki Z, Kemenesi G, Nándori A, Malik P, Bányai K, Károlyi HF, Nagy Á, Sós E, Banović P, et al. Multipurpose Passive Surveillance of Bat-Borne Viruses in Hungary: Lyssaviruses and Filoviruses in Focus. Animals. 2025; 15(24):3590. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243590

Chicago/Turabian StyleSzabó, Anna, Zsófia Lanszki, Gábor Kemenesi, Alexandra Nándori, Péter Malik, Krisztián Bányai, Henrik Fülöp Károlyi, Ágnes Nagy, Endre Sós, Pavle Banović, and et al. 2025. "Multipurpose Passive Surveillance of Bat-Borne Viruses in Hungary: Lyssaviruses and Filoviruses in Focus" Animals 15, no. 24: 3590. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243590

APA StyleSzabó, A., Lanszki, Z., Kemenesi, G., Nándori, A., Malik, P., Bányai, K., Károlyi, H. F., Nagy, Á., Sós, E., Banović, P., & Görföl, T. (2025). Multipurpose Passive Surveillance of Bat-Borne Viruses in Hungary: Lyssaviruses and Filoviruses in Focus. Animals, 15(24), 3590. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243590