A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus Vaccine Efficacy and Its Modifiers

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- (1)

- Studies in which swine vaccines are used for the prevention of epidemic diarrhea

- (2)

- The primary outcome must be included the fecal score

- (3)

- The research must include both a vaccine-immunized group and a control group

- (4)

- The study data must report the following for fecal score: Mean value (), Sample size (n), Standard deviation (SD) or Standard error (SE).

- (1)

- Studies exclusively using mice as animal models

- (2)

- conference abstracts, letters to the editor, and reviews

- (3)

- Literature with incomplete data or insufficient information for valid extraction

2.3. Database Formation

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

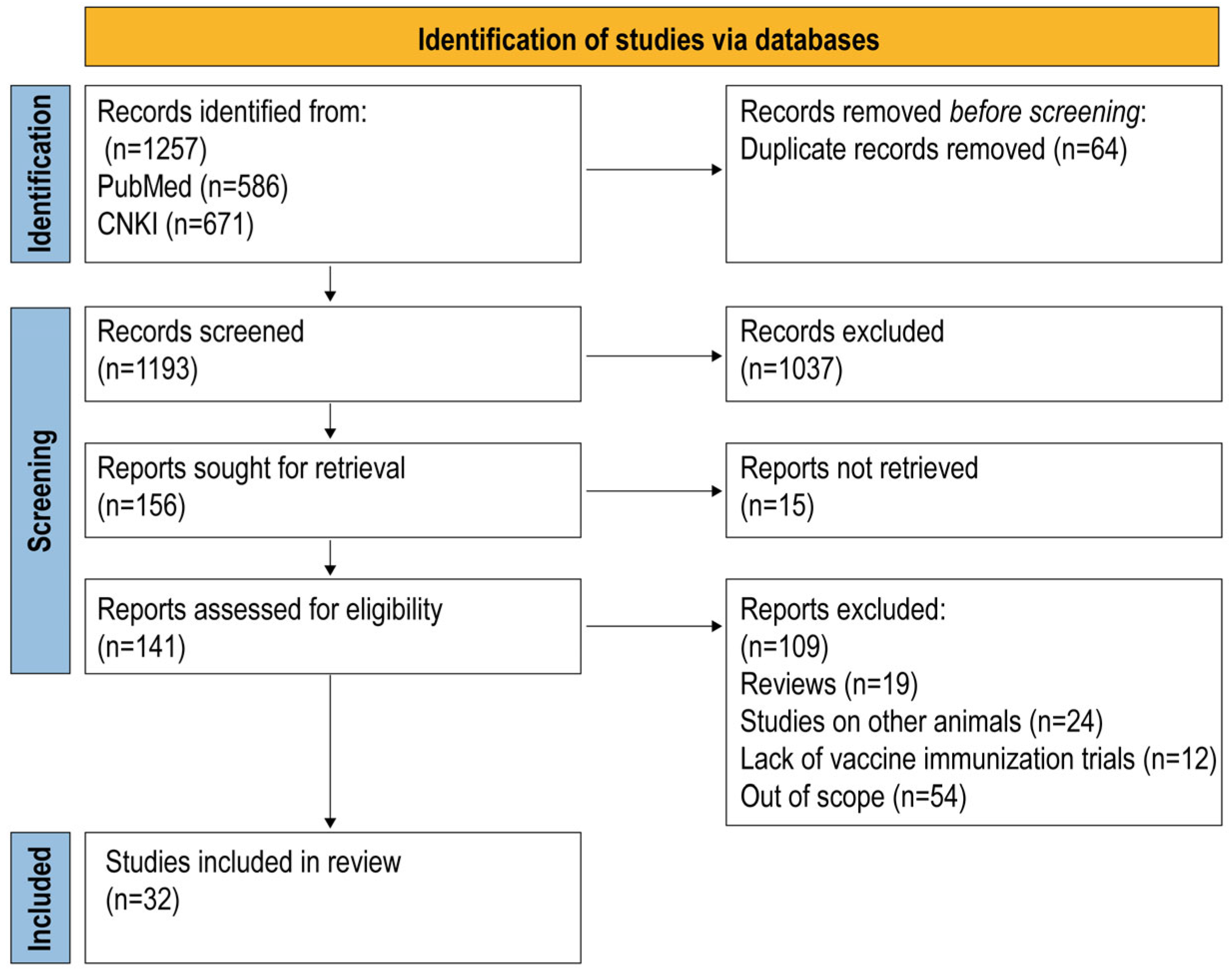

3.1. Study Selection and Data Extraction

3.2. Meta-Analysis of PEDV Vaccines Efficacy

3.3. Heterogeneity Assessment

3.4. Subgroup Analysis

3.4.1. Effect Analysis Based on Vaccine Type

3.4.2. Effect Analysis by Vaccination Target

3.4.3. Effect Analysis Based on Vaccination Frequency

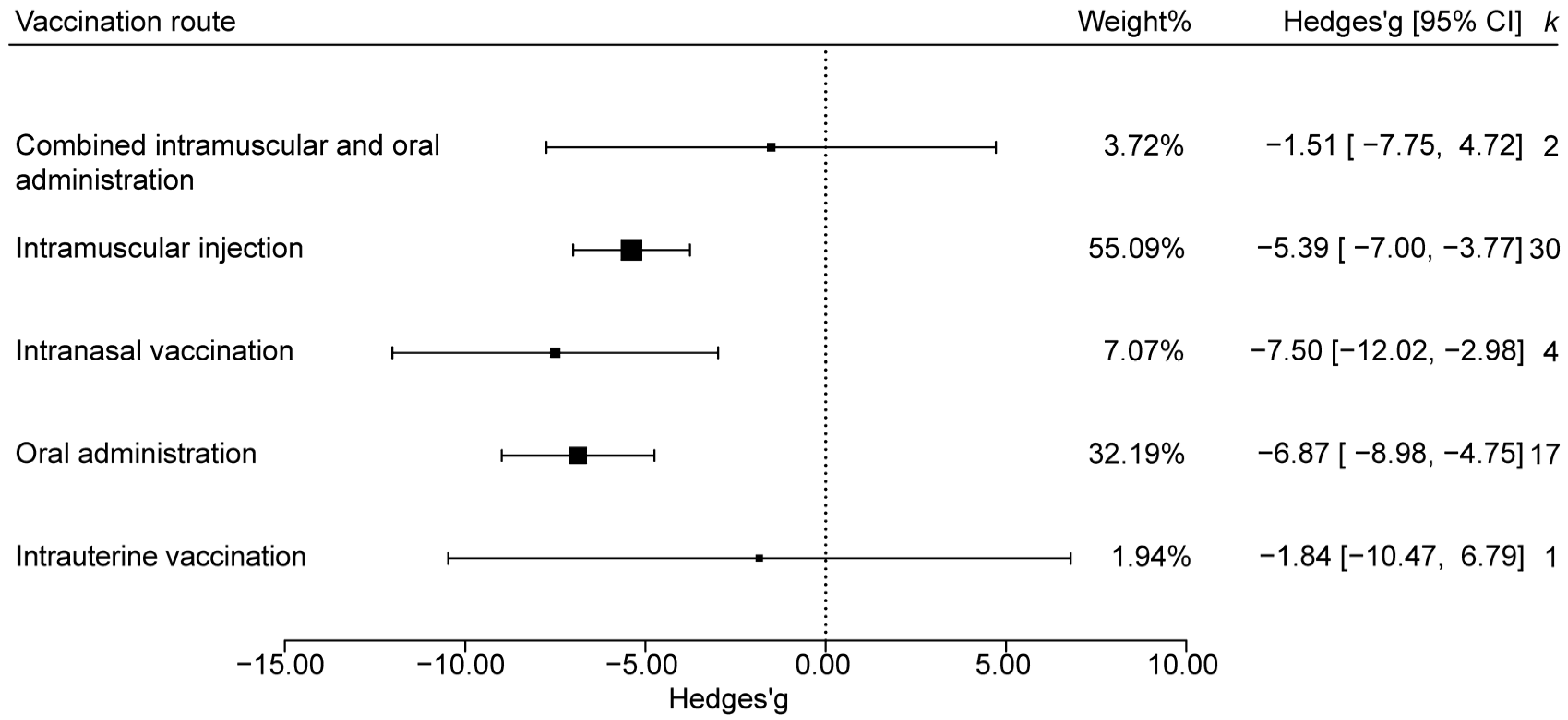

3.4.4. Effect Analysis by Vaccination Route

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lee, C. Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus: An emerging and re-emerging epizootic swine virus. Virol. J. 2015, 12, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pensaert, M.B.; de Bouck, P. A new coronavirus-like particle associated with diarrhea in swine. Arch. Virol. 1978, 58, 243–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, Z.; Lin, S.; Gao, M.; Shao, Y.; Li, S.; Chen, Q.; Cui, Y.; Hu, Y.; Liu, G. Insights into cross-species infection: Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus infections in the rodent. Virol. Sin. 2025, 40, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, J.; Miao, Y.; Bi, W.; Xiang, C.; Li, W.; Zhang, R.; Li, Q.; Yang, Z. Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus: Etiology, Epidemiology, Antigenicity, and Control Strategies in China. Animals 2024, 14, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, L.; Shang, Y.; Tan, R.; Ji, M.; Yue, X.; Wang, N.; Liu, J.; Wang, C.; Li, Y.; et al. Emergence and evolution of highly pathogenic porcine epidemic diarrhea virus by natural recombination of a low pathogenic vaccine isolate and a highly pathogenic strain in the spike gene. Virus Evol. 2020, 6, veaa049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, C.; Shi, H.; Qiu, H.; Liu, S.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Z.; Feng, L. Molecular epidemiology of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus in China. Arch. Virol. 2010, 155, 1471–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Li, D.; Yan, C.; Wu, C.; Han, F.; Bo, Z.; Shen, M.; Sun, Y.; Wang, L.; Zheng, H.; et al. Phylogenetic and Genetic Variation Analysis of Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus in East Central China during 2020–2023. Animals 2024, 14, 2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Du, L.; Fan, B.; Sun, B.; Zhou, J.; Guo, R.; Yu, Z.; Shi, D.; He, K.; Li, B. A flagellin-adjuvanted inactivated porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV) vaccine provides enhanced immune protection against PEDV challenge in piglets. Arch. Virol. 2020, 165, 1299–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, X.; Wang, Q. Prevention and Control of Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea: The Development of Recombination-Resistant Live Attenuated Vaccines. Viruses 2022, 14, 1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.E.; Jang, H.; Kim, J.H.; Hyun, B.H.; Shin, H.J. Immunization with porcine epidemic diarrhea virus harbouring Fc domain of IgG enhances antibody production in pigs. Vet. Q. 2020, 40, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yuan, W.; Peng, Q.; Zhang, F.; Ye, Y.; Huang, D.; Ding, Z.; Lin, L.; He, H.; et al. Evaluation of Cross-Protection between G1a- and G2a-Genotype Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Viruses in Suckling Piglets. Animals 2020, 10, 1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.W.; Xue, C.Y.; Cao, Y.C. Study on the dose-effect relationship of inactivated whole-virus vaccine against porcine epidemic diarrhea virus. Acta Vet. Zootech. Sin. 2022, 53, 1536–1543. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.; Xie, Y.; Liao, Q.; Jiao, Z.; Liang, R.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Tan, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhang, W.; et al. Development of a safe and broad-spectrum attenuated PEDV vaccine candidate by S2 subunit replacement. J. Virol. 2024, 98, e0042924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.E. Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea: Insights and Progress on Vaccines. Vaccines 2024, 12, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.C.; Chang, C.Y.; Tsai, P.S.; Chiou, H.Y.; Jeng, C.R.; Pang, V.F.; Chang, H.W. Efficacy of heat-labile enterotoxin B subunit-adjuvanted parenteral porcine epidemic diarrhea virus trimeric spike subunit vaccine in piglets. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 7499–7507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, H.; Liang, Z.; Lin, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Mei, K.; Zhao, M.; Huang, S. Research progress of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus S protein. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1396894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, S.; Guo, R.; Hu, M.; Sun, M.; Zhang, G.; Li, Y.; et al. Efficacy evaluation of a bivalent subunit vaccine against epidemic PEDV heterologous strains with low cross-protection. J. Virol. 2024, 98, e0130924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murtaza, A.; Hoa, N.T.; Dieu-Huong, D.; Afzal, H.; Tariq, M.H.; Cheng, L.T.; Chung, Y.C. Advancing PEDV Vaccination: Comparison between Inactivated and Flagellin N-Terminus-Adjuvanted Subunit Vaccines. Vaccines 2024, 12, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, F.; Jia, H.; Xiao, Q.; Fang, L.; Wang, Q. Prevention and Control of Swine Enteric Coronaviruses in China: A Review of Vaccine Development and Application. Vaccines 2023, 12, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Sreenivasan, C.; Uprety, T.; Gao, R.; Huang, C.; Lee, E.J.; Lawson, S.; Nelson, J.; Christopher-Hennings, J.; Kaushik, R.S.; et al. Piglet immunization with a spike subunit vaccine enhances disease by porcine epidemic diarrhea virus. npj Vaccines 2021, 6, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.Z.; Chen, L.; Zhang, R.; Chen, Z.; Shen, Y.J.; Zhou, B.J.; Wang, K.G.; Shan, C.L.; Zhu, E.P.; Cheng, Z.T. Overview of the recent advances in porcine epidemic diarrhea vaccines. Vet. J. 2024, 304, 106097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, X.Q.; Liu, Y.; Chen, X.M.; Wang, C.Y.; Cui, J.T.; Zheng, L.L.; Ma, S.J.; Chen, H.Y. Construction and Immunogenicity of a Recombinant Porcine Pseudorabies Virus (PRV) Expressing the Major Neutralizing Epitope Regions of S1 Protein of Variant PEDV. Viruses 2024, 16, 1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, M.W.; Vijayakumar, R. A Guide to Conducting a Meta-Analysis. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2016, 26, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y.; Hui, D.; Zhang, D. Elevated CO2 stimulates net accumulations of carbon and nitrogen in land ecosystems: A meta-analysis. Ecology 2006, 87, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer, G. meta: An R package for meta-analysis. R News 2007, 7, 40–45. [Google Scholar]

- Subramaniam, S.; Yugo, D.M.; Heffron, C.L.; Rogers, A.J.; Sooryanarain, H.; LeRoith, T.; Overend, C.; Cao, D.; Meng, X.J. Vaccination of sows with a dendritic cell-targeted porcine epidemic diarrhea virus S1 protein-based candidate vaccine reduced viral shedding but exacerbated gross pathological lesions in suckling neonatal piglets. J. Gen. Virol. 2018, 99, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Clark-Deener, S.; Gillam, F.; Heffron, C.L.; Tian, D.; Sooryanarain, H.; LeRoith, T.; Zoghby, J.; Henshaw, M.; Waldrop, S.; et al. Virus-like particle vaccine with B-cell epitope from porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV) incorporated into hepatitis B virus core capsid provides clinical alleviation against PEDV in neonatal piglets through lactogenic immunity. Vaccine 2020, 38, 5212–5218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, X.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, J.; Chen, T.; Deng, G.; Yue, H.; Tang, C.; Wu, X.; Yu, J.; Zhang, B. Immunogenicity and protective efficacy of recombinant adenovirus expressing a novel genotype G2b PEDV spike protein in protecting newborn piglets against PEDV. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e02403-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.; Liu, M.; Yang, S.; Xu, J.; Hou, Y.J.; Liu, D.; Tang, Q.; Zhu, H.; Wang, Q. A recombination-resistant genome for live attenuated and stable PEDV vaccines by engineering the transcriptional regulatory sequences. J. Virol. 2023, 97, e0119323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, L.; Chen, Q.; Fredericks, L.; Gauger, P.; Bandrick, M.; Keith, M.; Giménez-Lirola, L.; Magstadt, D.; Yim-Im, W.; Welch, M.; et al. Evaluation of the Efficacy of an S-INDEL PEDV Strain Administered to Pregnant Gilts against a Virulent Non-S-INDEL PEDV Challenge in Newborn Piglets. Viruses 2022, 14, 1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Du, L.; Yu, Z.; Sun, B.; Xu, X.; Fan, B.; Guo, R.; Yuan, W.; He, K. Poly (d,l-lactide-co-glycolide) nanoparticle-entrapped vaccine induces a protective immune response against porcine epidemic diarrhea virus infection in piglets. Vaccine 2017, 35, 7010–7017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Ke, H.; Kim, J.; Yoo, D.; Su, Y.; Boley, P.; Chepngeno, J.; Vlasova, A.N.; Saif, L.J.; Wang, Q. Engineering a Live Attenuated Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus Vaccine Candidate via Inactivation of the Viral 2′-O-Methyltransferase and the Endocytosis Signal of the Spike Protein. J. Virol. 2019, 93, e00406-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makadiya, N.; Brownlie, R.; van den Hurk, J.; Berube, N.; Allan, B.; Gerdts, V.; Zakhartchouk, A. S1 domain of the porcine epidemic diarrhea virus spike protein as a vaccine antigen. Virol. J. 2016, 13, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, X.; Kong, F.; Xu, J.; Liu, M.; Wang, Q. Mutations in Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus nsp1 Cause Increased Viral Sensitivity to Host Interferon Responses and Attenuation In Vivo. J. Virol. 2022, 96, e00469-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, T.; Oroku, K.; Ohshima, Y.; Furuya, Y.; Sasakawa, C. Efficacy of genogroup 1 based porcine epidemic diarrhea live vaccine against genogroup 2 field strain in Japan. Virol. J. 2018, 15, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Hao, H.; Li, M.; Niu, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Li, Q. Expression and Purification of a PEDV-Neutralizing Antibody and Its Functional Verification. Viruses 2021, 13, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Fan, B.; Song, X.; Gao, J.; Guo, R.; Yi, C.; He, Z.; Hu, H.; Jiang, J.; Zhao, L.; et al. PEDV-spike-protein-expressing mRNA vaccine protects piglets against PEDV challenge. mBio 2024, 15, e02958-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Ma, Z.; Han, W.; Chang, C.; Li, Y.; Guo, X.; Zheng, Z.; Feng, Y.; Xu, L.; Zheng, H.; et al. Deletion of a 7-amino-acid region in the porcine epidemic diarrhea virus envelope protein induces higher type I and III interferon responses and results in attenuation in vivo. J. Virol. 2023, 97, e00847-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Q.; Fan, B.; Song, X.; He, W.; Wang, C.; Zhao, Y.; Guo, W.; Zhang, X.; Liu, S.; Gao, J.; et al. Genetic signatures associated with the virulence of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus AH2012/12. J. Virol. 2023, 97, e01063-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yi, W.; Qin, H.; Wang, Q.; Guo, R.; Pan, Z. A Genetically Engineered Bivalent Vaccine Coexpressing a Molecular Adjuvant against Classical Swine Fever and Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Singh, P.; Pillatzki, A.; Nelson, E.; Webb, B.; Dillberger-Lawson, S.; Ramamoorthy, S. A Minimally Replicative Vaccine Protects Vaccinated Piglets Against Challenge With the Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus. Front. Vet. Sci. 2019, 6, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.W.; Chang, M.H.; Chang, H.W.; Wu, T.Y.; Chang, Y.C. Parenterally Administered Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus-Like Particle-Based Vaccine Formulated with CCL25/28 Chemokines Induces Systemic and Mucosal Immune Protectivity in Pigs. Viruses 2020, 12, 1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, D.; Tian, D.; Yu, H.; Dar, N.; Rajasekaran, V.; Meng, S.; Mahsoub, H.M.; Sooryanarain, H.; Wang, B.; Heffron, C.L.; et al. Killed whole-genome reduced-bacteria surface-expressed coronavirus fusion peptide vaccines protect against disease in a porcine model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2025622118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, C.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Yang, Q. Feeding with 4,4′-diaponeurosporene-producing Bacillus subtilis enhances the lactogenic immunity of sow. BMC Vet. Res. 2023, 19, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, X.; Lin, H.; Li, B.; He, K.; Fan, H. Efficacy and immunogenicity of recombinant swinepox virus expressing the truncated S protein of a novel isolate of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus. Arch. Virol. 2017, 162, 3779–3789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amimo, J.O.; Michael, H.; Chepngeno, J.; Jung, K.; Raev, S.A.; Paim, F.C.; Lee, M.V.; Damtie, D.; Vlasova, A.N.; Saif, L.J. Maternal immunization and vitamin A sufficiency impact sow primary adaptive immunity and passive protection to nursing piglets against porcine epidemic diarrhea virus infection. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1397118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Yang, D.K.; Kim, H.H.; Cho, I.S. Efficacy of inactivated variant porcine epidemic diarrhea virus vaccines in growing pigs. Clin. Exp. Vaccine Res. 2018, 7, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, P.; Fourie, K.R.; Ng, S.; Hamonic, G.; Bérubé, N.; Popowych, Y.; Wilson, H.L. Intrauterine immunizations trigger antigen-specific mucosal and systemic immunity in pigs and passive protection in suckling piglets. Vaccine 2021, 39, 6322–6332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.M.; Ghimire, S.; Hou, Y.; Boley, P.; Langel, S.N.; Vlasova, A.N.; Saif, L.J.; Wang, Q. Pathogenicity and immunogenicity of attenuated porcine epidemic diarrhea virus PC22A strain in conventional weaned pigs. BMC Vet. Res. 2019, 15, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langel, S.N.; Paim, F.C.; Alhamo, M.A.; Buckley, A.; Van Geelen, A.; Lager, K.M.; Vlasova, A.N.; Saif, L.J. Stage of Gestation at Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus Infection of Pregnant Swine Impacts Maternal Immunity and Lactogenic Immune Protection of Neonatal Suckling Piglets. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Chen, L.; Gao, L.; Yuan, X.; Ma, Z.; Fan, H. Epidemic strain YC2014 of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus could provide piglets against homologous challenge. Virol. J. 2016, 13, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, T.T.; Trinh, V.T.; Tran, H.X.; Le, P.T.T.; Nguyen, T.T.; Hoang, H.T.T.; Pham, M.D.; Conrad, U.; Pham, N.B.; Chu, H.H. The immunogenicity of plant-based COE-GCN4pII protein in pigs against the highly virulent porcine epidemic diarrhea virus strain from genotype 2. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 940395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Won, H.; Lee, D.U.; Jang, G.; Noh, Y.H.; Lee, S.C.; Choi, H.W.; Yoon, I.J.; Yoo, H.S.; Lee, C. Generation and protective efficacy of a cold-adapted attenuated genotype 2b porcine epidemic diarrhea virus. J. Vet. Sci. 2019, 20, e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, D.; Park, B. Porcine epidemic diarrhoea virus: A comprehensive review of molecular epidemiology, diagnosis, and vaccines. Virus Genes 2012, 44, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Yin, S.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, L.; Teng, Z.; Qiao, L.; Wang, Y.; Yu, J.; Zang, H.; Ding, Y.; et al. Spike 1 trimer, a nanoparticle vaccine against porcine epidemic diarrhea virus induces protective immunity challenge in piglets. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1386136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.E.; Kang, K.J.; Ryu, J.H.; Park, J.Y.; Jang, H.; Sung, D.J.; Kang, J.G.; Shin, H.J. Porcine epidemic diarrhea vaccine evaluation using a newly isolated strain from Korea. Vet. Microbiol. 2018, 221, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Qiu, C.; Tian, H.; Zhu, X.; Yin, B.; Zhou, Z.; Li, X.; Zhao, J. Host restriction factors against porcine epidemic diarrhea virus: A mini-review. Vet. Res. 2025, 56, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Q.; Mao, Q.; Peng, X.; He, Z.; Lu, S.; Zhang, J.; Gao, F.; Bian, L.; An, C.; Yu, W.; et al. Immunogenicity and protective efficacy of a recombinant protein subunit vaccine and an inactivated vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 variants in non-human primates. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nestić, D.; Božinović, K.; Drašković, I.; Kovačević, A.; van den Bosch, J.; Knežević, J.; Custers, J.; Ambriović-Ristov, A.; Majhen, D. Human Adenovirus Type 26 Induced IL-6 Gene Expression in an αvβ3 Integrin- and NF-κB-Dependent Manner. Viruses 2022, 14, 672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.L.; Li, Y.X.; Wang, H.J.; Li, Y.F.; Liu, S.M.; Liu, Q.Y.; Wang, X.R. Research progress on porcine epidemic diarrhea vaccines. Acta Vet. Zootech. Sin. 2025, 12, 1–28. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Merkuleva, I.A.; Shcherbakov, D.N.; Borgoyakova, M.B.; Shanshin, D.V.; Rudometov, A.P.; Karpenko, L.I.; Belenkaya, S.V.; Isaeva, A.A.; Nesmeyanova, V.S.; Kazachinskaia, E.I.; et al. Comparative Immunogenicity of the Recombinant Receptor-Binding Domain of Protein S SARS-CoV-2 Obtained in Prokaryotic and Mammalian Expression Systems. Vaccines 2022, 10, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y.E.; Feng, L.; Li, W.J.; Wang, M.; Ma, S.Q. Development of an attenuated strain of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus. Chin. J. Prev. Vet. Med. 1998, 6, 10–13. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Kweon, C.H.; Kwon, B.J.; Lee, J.G.; Kwon, G.O.; Kang, Y.B. Derivation of attenuated porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV) as vaccine candidate. Vaccine 1999, 17, 2546–2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, T.; Takeyama, N.; Katsumata, A.; Tuchiya, K.; Kodama, T.; Kusanagi, K. Mutations in the spike gene of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus associated with growth adaptation in vitro and attenuation of virulence in vivo. Virus Genes 2011, 43, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zang, Y.; Tian, Y.; Li, Y.; Xue, R.; Hu, L.; Zhang, D.; Sun, S.; Wang, G.; Chen, J.; Lan, Z.; et al. Recombinant Lactobacillus acidophilus expressing S(1) and S(2) domains of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus could improve the humoral and mucosal immune levels in mice and sows inoculated orally. Vet. Microbiol. 2020, 248, 108827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen Thi, T.H.; Chen, C.C.; Chung, W.B.; Chaung, H.C.; Huang, Y.L.; Cheng, L.T.; Ke, G.M. Antibody Evaluation and Mutations of Antigenic Epitopes in the Spike Protein of the Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus from Pig Farms with Repeated Intentional Exposure (Feedback). Viruses 2022, 14, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, P.; Du, J.B.; Ning, H.B.; Wang, Z.B.; Liu, M.M.; Wang, H.L.; He, S. Clinical evaluation of the immune efficacy of an inactivated porcine epidemic diarrhea vaccine. Mod. J. Anim. Husb. Vet. Med. 2022, 1, 39–42. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Hu, G.; Liu, S.; Ren, G.; Gao, L.; Zhao, Z.; Geng, R.; Wang, D.; Shen, X.; Chen, F.; et al. Evaluating passive immunity in piglets from sows vaccinated with a PEDV S protein subunit vaccine. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1498610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, E.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Huang, L.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Q. Comparison of oral and nasal immunization with inactivated porcine epidemic diarrhea virus on intestinal immunity in piglets. Exp. Ther. Med. 2020, 20, 1596–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Moderator Variables | Type | k |

|---|---|---|

| vaccine type | Recombinant viral vector vaccine | 13 |

| Nucleic acid vaccine | 1 | |

| Live attenuated vaccine | 16 | |

| Inactivated vaccine | 20 | |

| Subunit vaccine | 4 | |

| vaccination target | Piglet | 27 |

| Sow | 25 | |

| Boar | 2 | |

| vaccination route | Intranasal vaccination | 4 |

| Intrauterine vaccination | 1 | |

| Oral administration | 17 | |

| Intramuscular injection | 30 | |

| Combined intramuscular and oral administration | 2 | |

| vaccination frequency | single-dose vaccination | 13 |

| two-dose vaccination | 33 | |

| three-dose vaccination | 6 | |

| seven-dose vaccination | 2 |

| Influencing Factor | k | QM | PQM |

|---|---|---|---|

| vaccine type | 54 | 85.63 | <0.001 |

| vaccination target | 54 | 86.90 | <0.001 |

| vaccination frequency | 54 | 88.80 | <0.001 |

| vaccination route | 54 | 93.87 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, S.; Niu, S.; Yao, B.; Chen, Q.; Ma, W.; Luo, J.; Zheng, H.; Xu, G.; Wu, T.; Yao, W.; et al. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus Vaccine Efficacy and Its Modifiers. Animals 2025, 15, 3592. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243592

Li S, Niu S, Yao B, Chen Q, Ma W, Luo J, Zheng H, Xu G, Wu T, Yao W, et al. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus Vaccine Efficacy and Its Modifiers. Animals. 2025; 15(24):3592. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243592

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Shaomei, Shuizhu Niu, Bo Yao, Qianlin Chen, Wenjie Ma, Jie Luo, Hua Zheng, Guoyang Xu, Tao Wu, Wei Yao, and et al. 2025. "A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus Vaccine Efficacy and Its Modifiers" Animals 15, no. 24: 3592. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243592

APA StyleLi, S., Niu, S., Yao, B., Chen, Q., Ma, W., Luo, J., Zheng, H., Xu, G., Wu, T., Yao, W., Yang, L., & Fu, L. (2025). A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus Vaccine Efficacy and Its Modifiers. Animals, 15(24), 3592. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243592