LPS-Induced Inflammation and Preconditioning in Rainbow Trout: Markers of Innate Immunity and Oxidative Stress

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Fish and Rearing Conditions

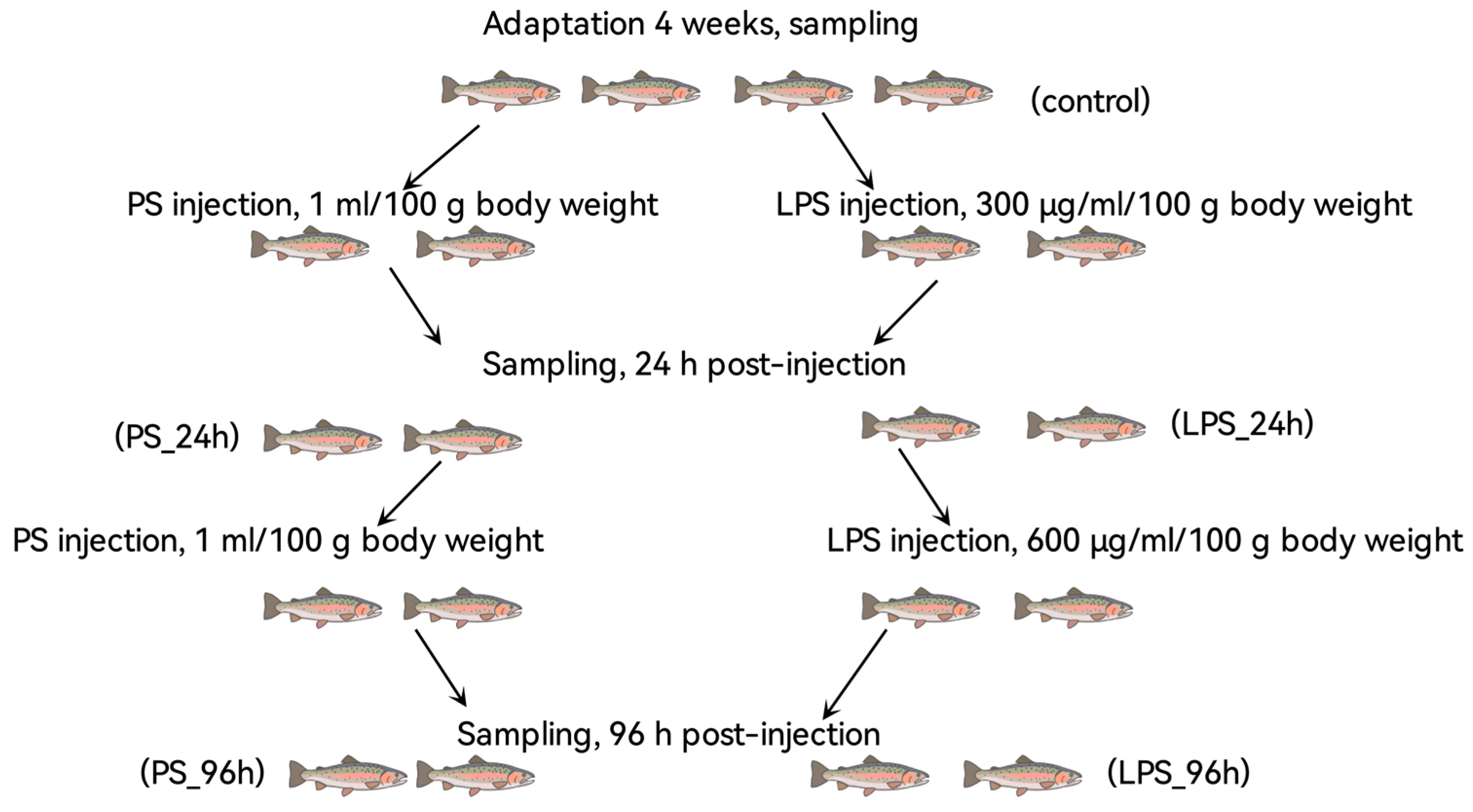

2.2. Experimental Design and Sampling

2.3. Morphometric and Organosomatic Indices

2.4. Dose-Finding Study

2.5. Analysis of il1ß and il8 Gene Expression in Spleen

2.6. Determination of Serum Bactericidal Activity (SBA)

2.7. Serum and Hepatic Biochemical Analyses

2.8. Blood Smear Microscopy

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Morphometric and Organosomatic Indices and Welfare of Fish

3.2. Interleukin Gene Expression in the Spleen

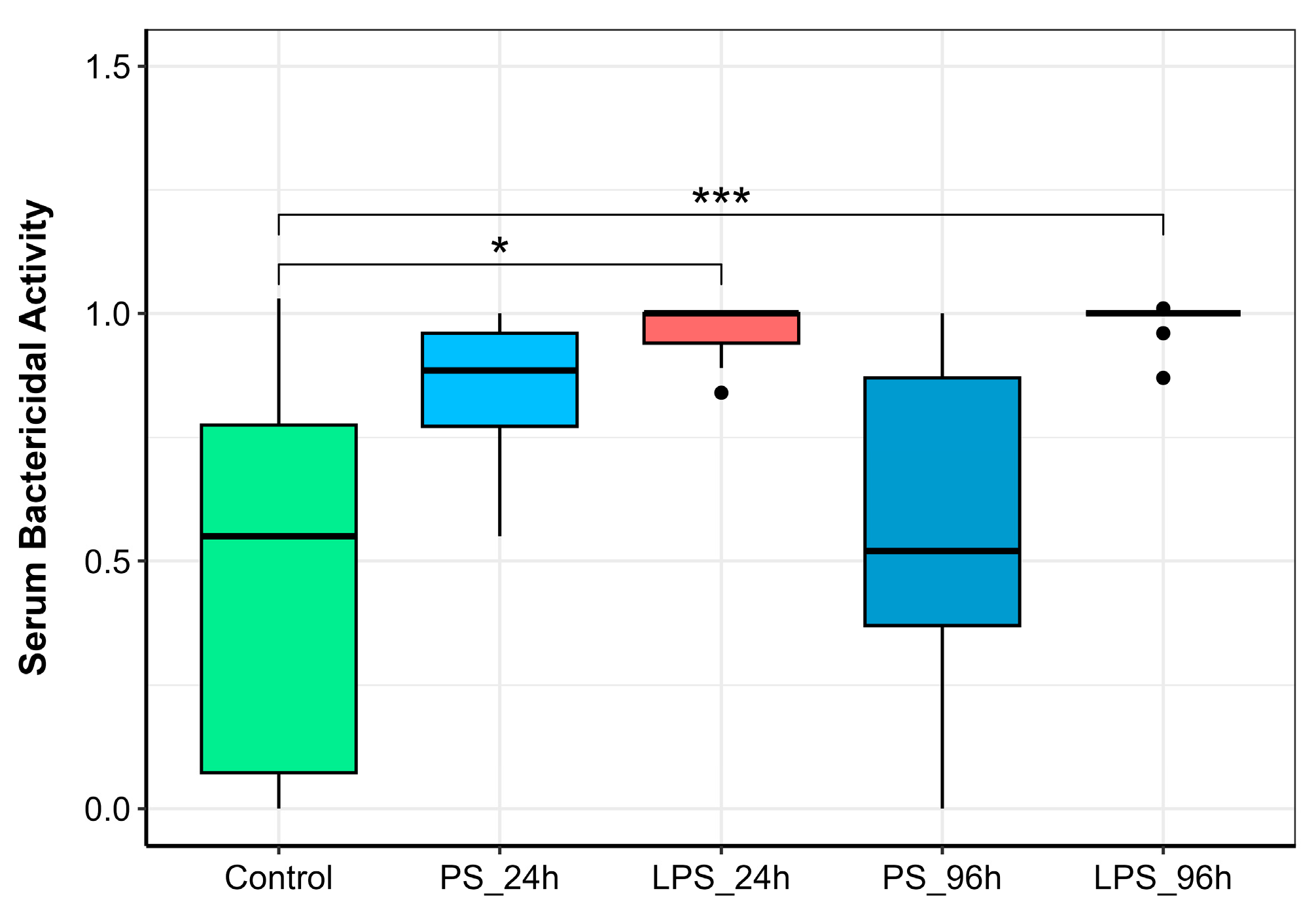

3.3. Serum Bactericidal Activity (SBA)

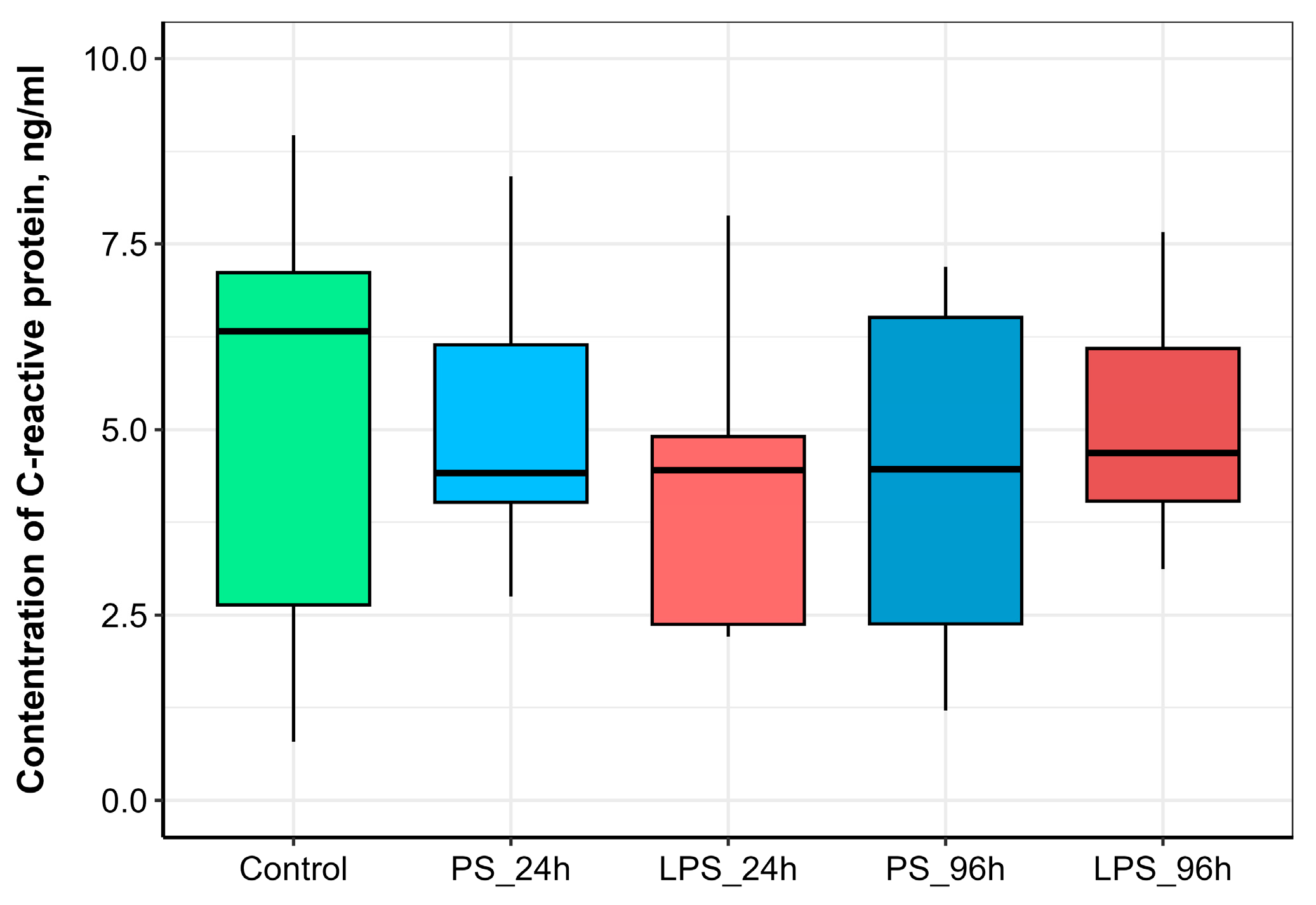

3.4. Serum C-Reactive Protein (CRP) Concentration

3.5. Hepatic Antioxidant Enzyme Activities

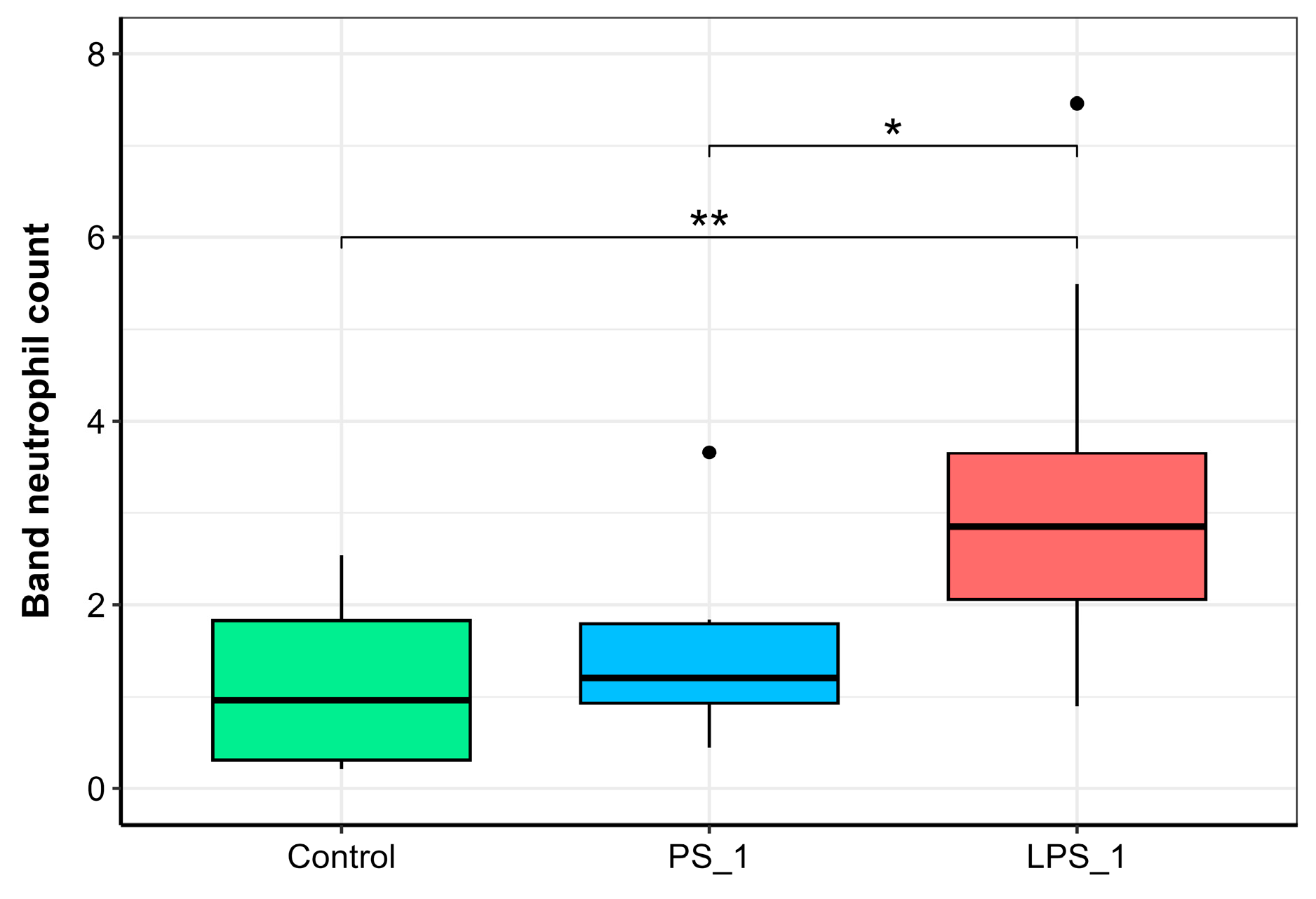

3.6. Peripheral Blood Leukocyte Profiles

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CAT | catalase |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| GST | glutathione-G-transferase |

| HSI | hepatosomatic index |

| il1ß | interleukin 1β |

| il8 | interleukin 8 |

| LPS | lipopolysaccharide |

| PS | physiological saline |

| SBA | serum bactericidal activity |

| SOD | superoxide dismutase |

| SSI | splenosomatic index |

References

- D’Agaro, E.; Gibertoni, P.P.; Esposito, S. Recent trends and economic aspects in the rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) sector. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okeke, E.S.; Chukwudozie, K.I.; Nyaruaba, R.; Ita, R.E.; Oladipo, A.; Ejeromedoghene, O.; Atakpa, E.O.; Agu, C.V.; Okoye, C.O. Antibiotic resistance in aquaculture and aquatic organisms: A review of current nanotechnology applications for sustainable management. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2022, 29, 69241–69274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharathi, S.; Cheryl, A.; Rajagopalasamy, C.B.T.; Uma, A.; Ahilan, B.; Aanand, S. Functional feed additives used in fish feeds. Intern. J. Fisher. Aquat. Stud. 2019, 7, 44–52. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, D.; Wojnarowski, K.; Cholewińska, P.; Palić, D. Current trends in approaches to prevent and control antimicrobial resistance in aquatic veterinary medicine. Pathogens 2025, 14, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- One Health High-Level Expert Panel (OHHLEP). One Health: A new definition for a sustainable and healthy future. PLoS Pathol. 2022, 18, e1010537. [CrossRef]

- Rombout, J.H.W.M.; Huttenhuis, H.B.T.; Picchietti, S.; Scapigliati, G. Phylogeny and ontogeny of fish leucocytes. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2005, 19, 441–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uribe, C.; Folch, H.; Enríquez, R.; Moran, G.J.V.M. Innate and adaptive immunity in teleost fish: A review. Vet. Med. 2011, 56, 486–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Kumar, V.; Kumar, V.; Behera, B.K. Acute phase proteins and their potential role as an indicator for fish health and in diagnosis of fish diseases. Prot. Pept. Lett. 2017, 24, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sproston, N.R.; Ashworth, J.J. Role of C-reactive protein at sites of inflammation and infection. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinarello, C.A. Proinflammatory cytokines. Chest J. 2000, 118, 503–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurpe, S.R.; Sukhovskaya, I.V.; Borvinskaya, E.V.; Morozov, A.A.; Parshukov, A.N.; Malysheva, I.E.; Vasileva, A.V.; Chechkova, N.A.; Kuchko, T.Y. Physiological and biochemical characteristics of rainbow trout with severe, moderate and asymptomatic course of Vibrio anguillarum infection. Animals 2022, 12, 2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnadóttir, B. Innate immunity of fish (overview). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2006, 20, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stacy, N.; Hollinger, C.; Arnold, J.E.; Cray, C.; Pendl, H.; Nelson, P.; Harvey, J. Left shift and toxic change in heterophils and neutrophils of non-mammalian vertebrates: A comparative review, image atlas, and practical considerations. Vet. Clin. Pathol. 2022, 51, 18–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montali, R.J. Comparative pathology of inflammation in the higher vertebrates (reptiles, birds and mammals). J. Comp. Pathol. 1988, 99, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopecka, J.; Pempkowiak, J. Temporal and spatial variations of selected biomarker activities in flounder (Platichthys flesus) collected in the Baltic proper. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2008, 70, 379–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiens, G.D.; Vallejo, R.L.; Leeds, T.D.; Palti, Y.; Hadidi, S.; Liu, S.; Evenhuis, J.P.; Welch, T.J.; Rexroad, C.E., III. Assessment of genetic correlation between bacterial cold water disease resistance and spleen index in a domesticated population of rainbow trout: Identification of QTL on chromosome Omy19. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e75749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braunbeck, T.; Storch, V.; Bresch, H. Species-specific reaction of liver ultrastructure in zebra fish (Brachydanio rerio) and trout (Salmo gairdneri) after prolonged exposure to 4-chloroaniline. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 1990, 19, 405–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, J.M.; Bahadur, A. Histopathological manifestations of sub-lethal toxicity of copper ions in Catla catla. Am.-Eur. J. Toxicol. Sci. 2011, 4, 01–05. [Google Scholar]

- Hoar, R.M. Developmental toxicity: Extrapolation across species. J. Am. Coll. Toxicol. 1995, 14, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadidi, S.; Glenney, G.W.; Welch, T.J.; Silverstein, J.T.; Wiens, G.D. Spleen size predicts resistance of rainbow trout to Flavobacterium psychrophilum challenge. J. Immunol. 2008, 180, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo, D.; Planas, J.V.; Bobe, J. Lipopolysaccharide administration in preovulatory rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) reduces egg quality. Aquaculture 2010, 300, 240–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossol, M.; Heine, H.; Meusch, U.; Quandt, D.; Klein, C.; Sweet, M.J.; Hauschildt, S. LPS-induced cytokine production in human monocytes and macrophages. Crit. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 31, 379–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, H.; Schmittner, M.; Duschl, A.; Horejs-Hoeck, J. Residual endotoxin contaminations in recombinant proteins are sufficient to activate human CD1c+ dendritic cells. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e113840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Tian, X.; Wang, Y.; Yan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Su, M.; Lv, H.; Li, K.; Hao, X.; Xing, X.; et al. Application of lipopolysaccharide in establishing inflammatory models. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 279, 135371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacKenzie, S.A.; Roher, N.; Boltana, S.; Goetz, F.W. Peptidoglycan, not endotoxin, is the key mediator of cytokine gene expression induced in rainbow trout macrophages by crude LPS. Mol. Immunol. 2010, 47, 1450–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliev, D.B.; Roach, J.C.; Mackenzie, S.A.; Planas, J.V.; Goetz, F.W. Endotoxin recognition: In fish or not in fish? FEBS Lett. 2005, 579, 6519–6528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falcão, M.A.P.; Dantas, M.D.S.; Rios, C.T.; Borges, L.P.; Serafini, M.R.; Guimarães, A.G.; Walker, C.I.B. Zebrafish as a tool for studying inflammation: A systematic review. Rev. Fisher. Sci. Aquacult 2022, 30, 101–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-López, A.; Tyrkalska, S.D.; Alcaraz-Pérez, F.; Cabas, I.; Candel, S.; Martínez Morcillo, F.J.; Sepulcre, M.P.; García-Moreno, D.; Cayuela, M.L.; Mulero, V. Evolution of LPS recognition and signaling: The bony fish perspective. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2023, 145, 104710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, J.W.; Ha, U.H.; Paek, S.H. In vitro inflammation inhibition model based on semi-continuous toll-like receptor biosensing. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e105212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rathinam, V.A.K.; Zhao, Y.; Shao, F. Innate immunity to intracellular LPS. Nat. Immunol. 2019, 20, 527–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Jiang, W.; Ma, H.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, H.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, J. Effect of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) on oxidative stress and apoptosis in immune tissues from Schizothorax prenanti. Animals 2025, 15, 1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kantserova, N.P.; Churova, M.V.; Lysenko, L.A.; Tushina, E.D.; Rodin, M.A.; Krupnova, M.Y.; Sukhovskaya, I.V. Effect of hyperthermia on proteases and growth regulators in the skeletal muscle of cultivated rainbow trout O. mykiss. Russ. J. Bioorg. Chem. 2020, 46, 1181–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavanagh, F. Photometric assaying. In Analytical Microbiology; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1972; Volume II, pp. 43–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, J.E.; Bailey, M.J. Quantitation of protein. Meth. Enzymol. 2009, 463, 73–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukhovskaya, I.; Borvinskaya, E.; Smirnov, L.; Nemova, N. Comparative analysis of the methods for determination of protein concentration–spectrophotometry in the 200–220 nm range and the Bradford protein assay. Transact. KarRC RAS. Exp. Biol. Ser. (In Russian). 2010, 2, 68–71. [Google Scholar]

- Fridovich, I. Superoxide dismutases. Ann. Rev. Biochem. 1975, 44, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beers, R.F.; Sizer, I.W. A spectrophotometric method for measuring the breakdown of hydrogen peroxide by catalase. J. Biol. Chem. 1952, 195, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habig, W.H.; Pabst, M.J.; Jakoby, W.B. Glutathione S-Transferases: The first enzymatic step in mercapturic acid formation. J. Biol. Chem. 1974, 249, 7130–7139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delamare-Deboutteville, J.; Wood, D.; Barnes, A.C. Response and function of cutaneous mucosal and serum antibodies in barramundi (Lates calcarifer) acclimated in seawater and freshwater. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2006, 21, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulsen, S.M.; Lunde, H.; Engstad, R.E.; Robertsen, B. In vivo effects of β-glucan and LPS on regulation of lysozyme activity and mRNA expression in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2003, 14, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetz, F.W.; Iliev, D.B.; McCauley, L.A.R.; Liarte, C.Q.; Tort, L.B.; Planas, J.V.; MacKenzie, S. Analysis of genes isolated from lipopolysaccharide-stimulated rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) macrophages. Mol. Immunol. 2004, 41, 1199–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslami, M.; Sayyah, M.; Soleimani, M.; Alizadeh, L.; Hadjighassem, M. Lipopolysaccharide preconditioning prevents acceleration of kindling epileptogenesis induced by traumatic brain injury. J. Neuroimmunol. 2015, 289, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.Y.; Yang, H.I.; Chen, S.D.; Shaw, F.Z.; Yang, D.I. Protective effects of lipopolysaccharide preconditioning against nitric oxide neurotoxicity. J. Neurosci. Res. 2008, 86, 1277–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.Y.; Huang, C.C.; Chang, K.F. Lipopolysaccharide preconditioning reduces neuroinflammation against hypoxic ischemia and provides long-term outcome of neuroprotection in neonatal rat. Pediatr. Res. 2009, 66, 254–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stetler, R.A.; Leak, R.K.; Gan, Y.; Li, P.; Zhang, F.; Hu, X.; Jing, Z.; Chen, J.; Zigmond, M.J.; Gao, Y. Preconditioning provides neuroprotection in models of CNS disease: Paradigms and clinical significance. Prog. Neurobiol. 2014, 114, 58–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.H.; Kim, H.R.; Kim, H.; Cho, J.H. CYLD suppresses LPS-induced inflammation through RIP1 deubiquitination in rainbow trout. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2025, 165, 110489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadowaki, T.; Yasui, Y.; Takahashi, Y.; Kohchi, C.; Soma, G.I.; Inagawa, H. Comparative immunological analysis of innate immunity activation after oral administration of wheat fermented extract to teleost fish. Anticancer Res. 2009, 29, 4871–4877. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Quiroz-Jara, M.; Casini, S.; Fossi, M.C.; Orrego, R.; Gavilán, J.F.; Barra, R. Integrated physiological biomarkers responses in wild fish exposed to the anthropogenic gradient in the Biobío river, South-Central Chile. Environ. Manag. 2021, 67, 1145–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, S.; Peddie, S.; Campos-Pérez, J.J.; Zou, J.; Secombes, C.J. The effect of intraperitoneally administered recombinant IL-1β on immune parameters and resistance to Aeromonas salmonicida in the rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2003, 27, 801–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Yao, C.-L. Molecular and expression characterizations of interleukin-8 gene in large yellow croaker (Larimichthys crocea). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2013, 34, 799–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Muiswinkel, W.B.; Nakao, M. A short history of research on immunity to infectious diseases in fish. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2014, 43, 130–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holland, M.C.H.; Lambris, J.D. The complement system in teleosts. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2002, 12, 399–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, S.; Hayes, M.; Simko, E.; Lumsden, J. Plasma proteomic analysis of the acute phase response of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) to intraperitoneal inflammation and LPS injection. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2006, 30, 393–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodama, H.; Matsuoka, Y.; Tanaka, Y.; Liu, Y.; Iwasaki, T.; Watarai, S. Changes of C-reactive protein levels in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) sera after exposure to anti-ectoparasitic chemicals used in aquaculture. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2004, 16, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valavanidis, A.; Vlahogianni, T.; Dassenakis, M.; Scoullos, M. Molecular biomarkers of oxidative stress in aquatic organisms in relation to toxic environmental pollutants. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2006, 64, 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abele, D.; Brey, T.; Philipp, E. Treatise Online no. 92: Part N, Revised, Volume 1, Chapter 7: Ecophysiology of extant marine Bivalvia. Treatise Online 2017, 75, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, M.S.; Sandrini-Neto, L.; Neto, F.F.; Ribeiro, C.A.O.; Di Domenico, M.; Prodocimo, M.M. Biomarker responses in fish exposed to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs): Systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 242, 449–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wei, X.F.; Yang, Z.Y.; Zhu, R.; Li, D.L.; Shang, G.J.; Wang, H.T.; Meng, S.T.; Wang, Y.T.; Liu, S.Y.; et al. Alleviative effect of poly-β-hydroxybutyrate on lipopolysaccharide-induced oxidative stress, inflammation and cell apoptosis in Cyprinus carpio. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 253, 126784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, S.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Yang, L.; Qin, C.; Yan, X.; Nie, G. Establishment and characterization of yellow river carp (Cyprinus carpio haematopterus) muscle cell line and its application to fish virology and immunology. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2023, 139, 108859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, D.L.; Wütermann, J.E.M.; White, M.G. The blood cells of the Antarctic icefish Chaenocephalus aceratus Lönnberg: Light and electron microscopic observations. J. Fish. Biol. 1981, 19, 11–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Jalabi, W.; Shpargel, K.B.; Farabaugh, K.T.; Dutta, R.; Yin, X.; Kidd, G.J.; Bergmann, C.C.; Stohlman, S.A.; Trapp, B.D. Lipopolysaccharide-induced microglial activation and neuroprotection against experimental brain injury is independent of hematogenous TLR4. J. Neurosci. 2012, 32, 11706–11715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazio, F. Fish hematology analysis as an important tool of aquaculture: A review. Aquaculture 2019, 500, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havixbeck, J.J.; Rieger, A.M.; Wong, M.E.; Hodgkinson, J.W.; Barreda, D.R. Neutrophil contributions to the induction and regulation of the acute inflammatory response in teleost fish. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2015, 99, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nabi, N.; Ahmed, I.; Wani, G.B. Hematological and serum biochemical reference intervals of rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss cultured in Himalayan aquaculture: Morphology, morphometrics and quantification of peripheral blood cells. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 29, 2942–2957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palic, D.; Beck, L.S.; Palic, J.; Andreasen, C.B. Use of rapid cyto-chemical staining to characterize fish blood granulocytes in species of special concern and determine potential for function testing. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2011, 30, 646–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speirs, Z.C.; Loynes, C.A.; Mathiessen, H.; Elks, P.M.; Renshaw, S.A.; von Gersdorff Jørgensen, L. What can we learn about fish neutrophil and macrophage response to immune challenge from studies in zebrafish. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2024, 148, 109490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene | Sequence 5′ → 3′, F–Forward, R–Reverse | NCBI Accession Number | Amplicon Length, n.p. | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| actb | F:CCGGCCGCGACCTCACAGACTAC R:CGGCCGTGGTGGTGAAGCTGTAAC | NM_001124235 | 73 | [11] |

| ef1α | F: GGTGGTGTGGGTGAGTTTGAG R: AACCGCTTCTGGCTGTAGGG | NM_001124339 | 159 | [33] |

| il1ß | F: ACCGAGTTCAAGGACAAGGA R: CATTCATCAGGACCCAGCAC | NM_001124347 | 181 | [11] |

| il8 | F: TGTCGTTGTGCTCCTGG R: CCTGACCGCTCTTGCTC | NM_001124362.1 | 197 | [11] |

| Treatment/Index | Control, Pre-Treatment | PS_24h | LPS_24h | PS_96h | LPS_96h |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K | 1.25 ± 0.04 | 1.15 ± 0.06 | 1.12 ± 0.04 | 1.09 ± 0.02 | 1.09 ± 0.07 |

| HSI, % | 1.17 ± 0.09 | 0.99a ± 0.14 | 1.17 ± 0.07 | 0.82 ± 0.06 a,b | 0.93 ± 0.04 a,b,c |

| SSI, % | 0.09 ± 0.04 | 0.08 ± 0.05 | 0.11 ± 0.02 | 0.05 ± 0.02 | 0.08 ± 0.04 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sukhovskaya, I.V.; Tsekova, A.A.; Kantserova, N.P.; Balan, O.V.; Kuchko, T.Y.; Matrosova, S.V.; Belyaev, A.N.; Lysenko, L.A. LPS-Induced Inflammation and Preconditioning in Rainbow Trout: Markers of Innate Immunity and Oxidative Stress. Animals 2025, 15, 3589. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243589

Sukhovskaya IV, Tsekova AA, Kantserova NP, Balan OV, Kuchko TY, Matrosova SV, Belyaev AN, Lysenko LA. LPS-Induced Inflammation and Preconditioning in Rainbow Trout: Markers of Innate Immunity and Oxidative Stress. Animals. 2025; 15(24):3589. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243589

Chicago/Turabian StyleSukhovskaya, Irina V., Albina A. Tsekova, Nadezhda P. Kantserova, Olga V. Balan, Tamara Y. Kuchko, Svetlana V. Matrosova, Alexander N. Belyaev, and Liudmila A. Lysenko. 2025. "LPS-Induced Inflammation and Preconditioning in Rainbow Trout: Markers of Innate Immunity and Oxidative Stress" Animals 15, no. 24: 3589. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243589

APA StyleSukhovskaya, I. V., Tsekova, A. A., Kantserova, N. P., Balan, O. V., Kuchko, T. Y., Matrosova, S. V., Belyaev, A. N., & Lysenko, L. A. (2025). LPS-Induced Inflammation and Preconditioning in Rainbow Trout: Markers of Innate Immunity and Oxidative Stress. Animals, 15(24), 3589. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243589