Integrated Transcriptomic and Proteomic Analysis Associated with Knockdown and Overexpression Studies Revealed ECHDC1 as a Regulator of Intramuscular Fat Deposition in Cattle

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

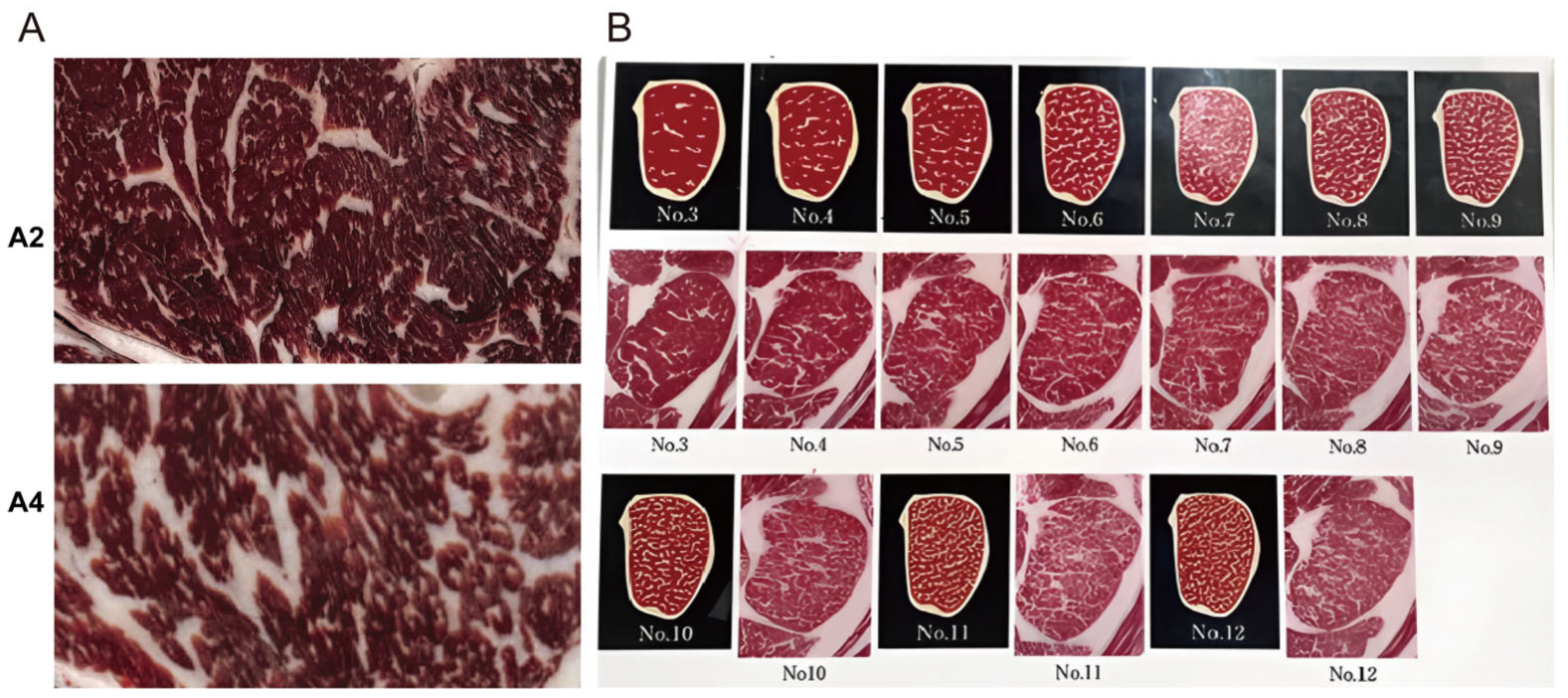

2.1. Animals, Samples and Ethical Approval

2.2. RNA Extraction, Sequencing, and Transcriptome Analysis

2.3. Protein Extraction, Sequencing, and Proteomics Analysis

2.4. Isolation and Induced Differentiation of Bovine Intramuscular Preadipocytes

2.5. Cell Transfection

2.6. Total RNA Extraction and RT-qPCR

2.7. Oil Red O Staining and Triglyceride (TG) Content Assay

2.8. Western Blot

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Transcriptomic Analysis Based on Differentially Expressed Genes

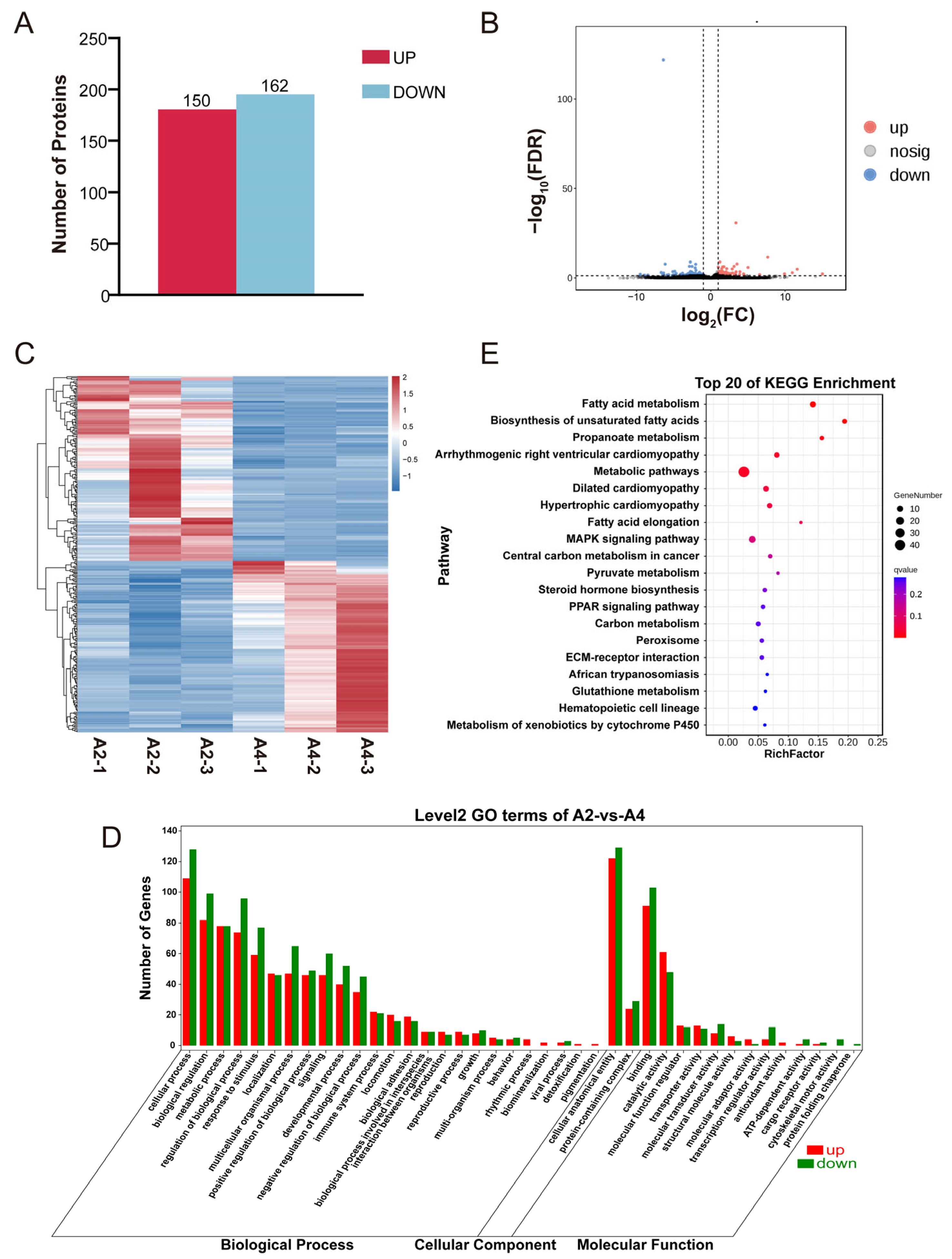

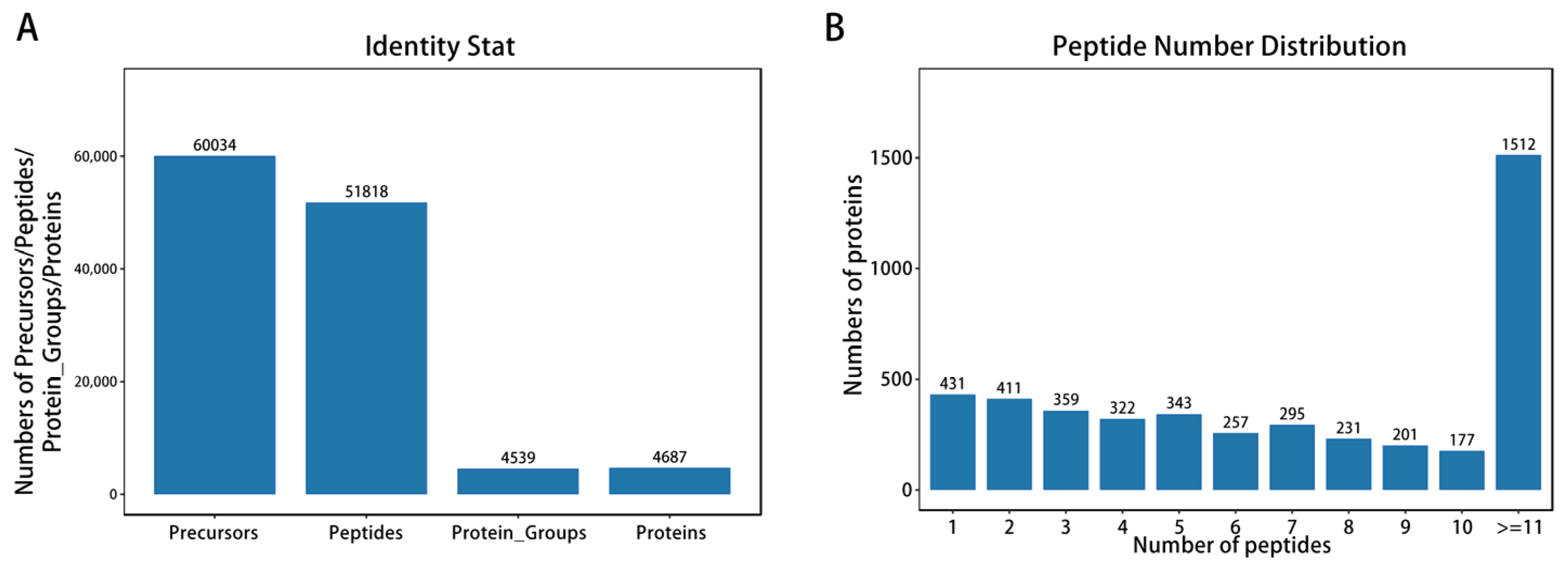

3.2. Proteomics Analysis Based on Differential Proteins

3.3. Analysis of the Association Between Transcriptome and Proteome

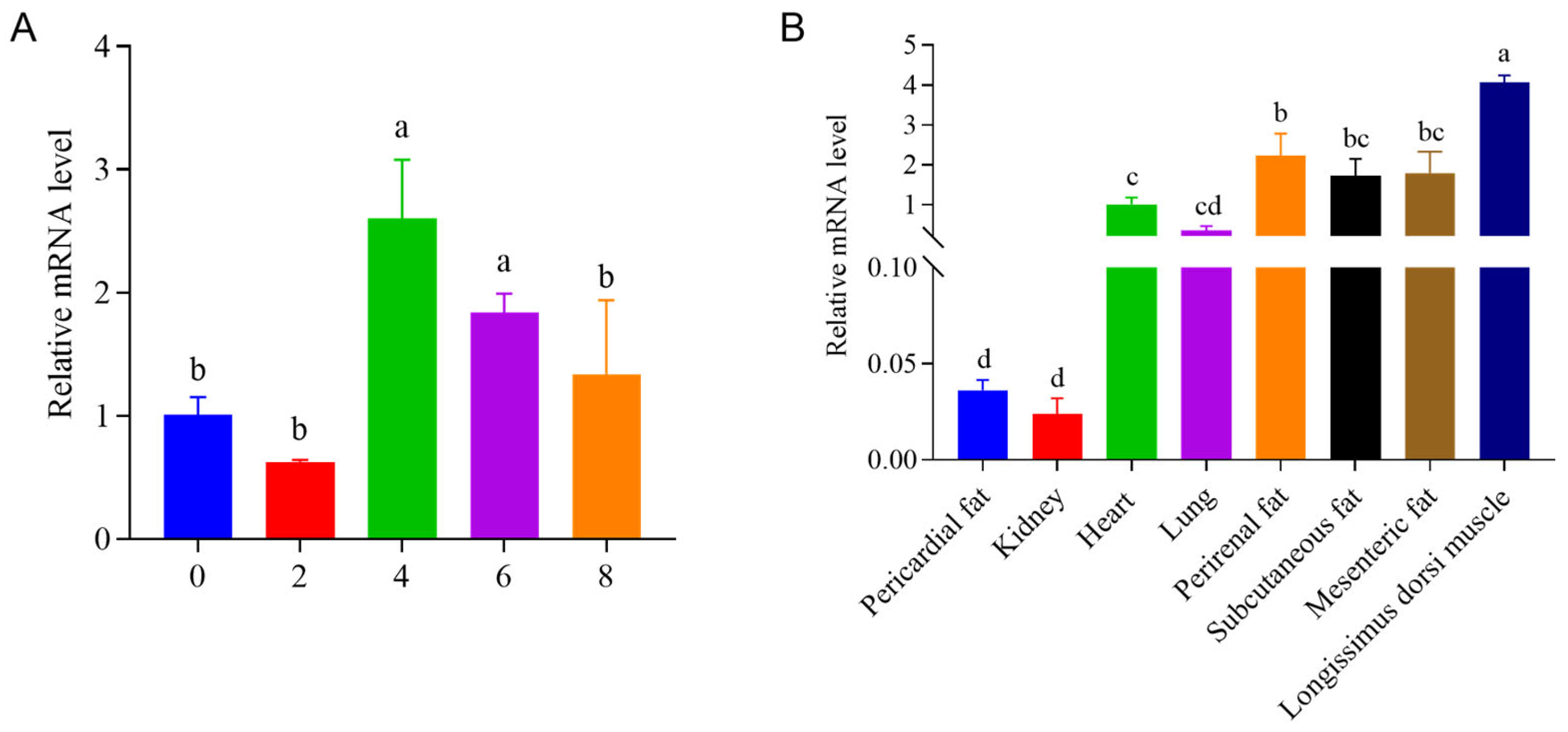

3.4. Temporal and Tissue ECHDC1 Relative mRNA Levels

3.5. Attenuation of ECHDC1 Inhibited the Adipogenesis of Intramuscular Preadipocytes

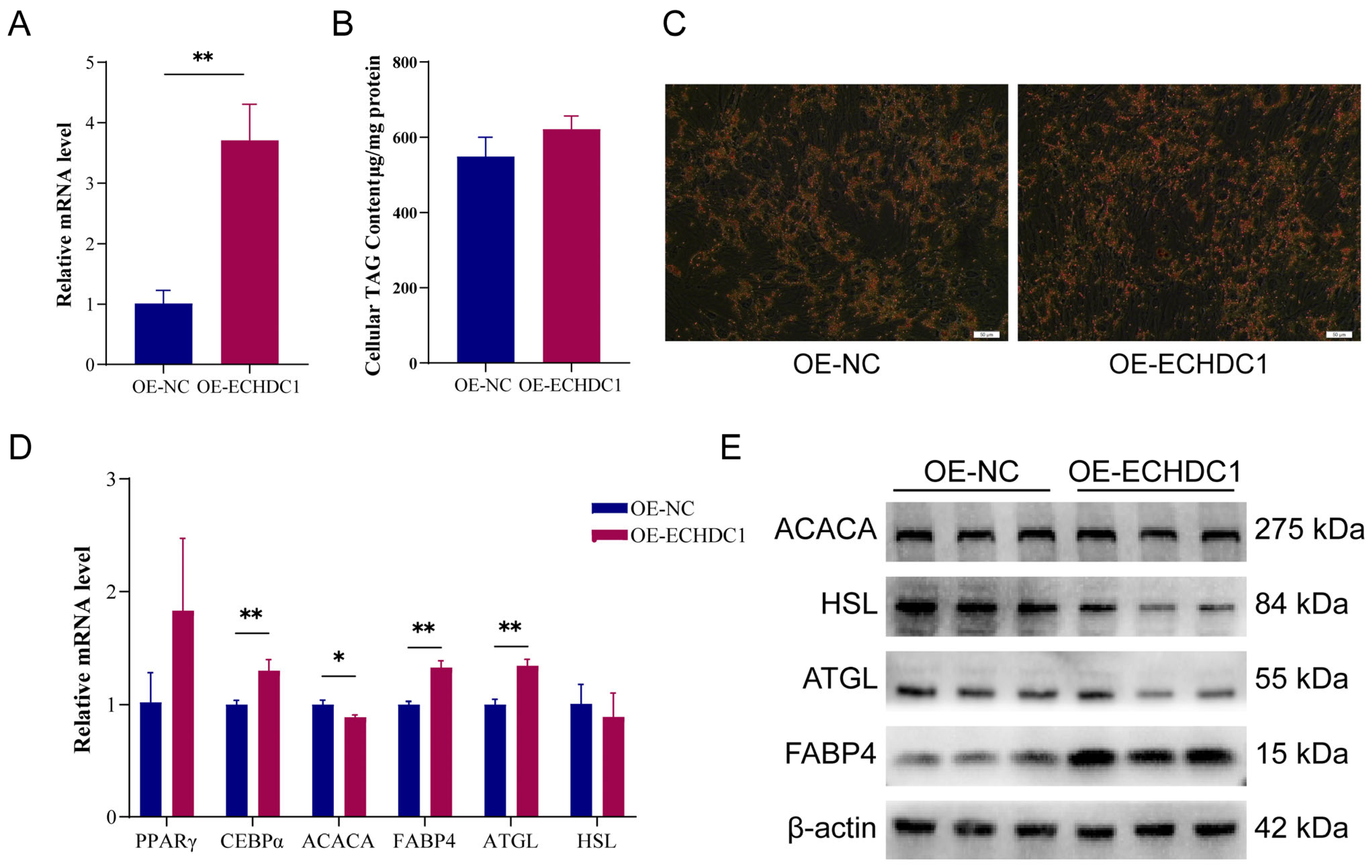

3.6. Overexpression of ECHDC1 Promoted the Adipogenesis of Intramuscular Preadipocytes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IMF | intramuscular fat |

| DEG | differentially expressed gene |

| DEP | differentially expressed protein |

| siRNA | small interfering RNA |

| CDS | Coding DNA Sequence |

| ATP | Adenosine Triphosphate |

| MPC | Mitochondrial Pyruvate Carrier |

| TAG/TG | Triacylglycerol |

| DMEM/F12 | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium/F12 Nutrient Mixture |

| MSC | mesenchymal stem cell |

| ECHDC1 | Enoyl-CoA Hydratase Domain-Containing Protein 1 |

| HSL | hormone-sensitive lipase |

| FABP4 | fatty acid binding protein 4 |

| PPARγ | peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ |

| C/EBPα | CCAAT/enhancer binding protein |

| ACACA | Acetyl-CoA carboxylase Alpha |

| ATGL | adipose triglyceride lipase |

| SREBP-1 | Sterol Regulatory Element-Binding Protein-1 |

| SNCG | Synuclein Gamma |

| ECHDC1 | Enoyl-CoA Hydratase Domain Containing 1 |

| FGF1 | Fibroblast Growth Factor 1 |

| CLEC11A | C-Type Lectin Domain Family 11 Member A |

| PHYHIPL | Phytanoyl-CoA Hydroxylase Interacting Protein-Like |

| RIDA | RAD51 Inhibitor Domain-Containing Protein |

| ACSS2 | Acyl-CoA Synthetase Short-Chain Family Member 2 |

| QPRT | Quinolinate Phosphoribosyltransferase |

| CDH2 | Cadherin 2 (N-Cadherin) |

| COL3A1 | Collagen Type III Alpha 1 Chain |

| H2AC11 | H2A Clustered Histone 11 |

| GSTA3 | Glutathione S-Transferase Alpha 3 |

| RGN | Regucalcin |

| TMSB15A | Thymosin Beta 15A |

| FIBIN | Fibulin 1 |

| PPP1R12B | Protein Phosphatase 1 Regulatory Subunit 12B |

| PDK4 | Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Kinase 4 |

| IFITM1 | Interferon-Induced Transmembrane Protein 1 |

| CFH | Complement Factor H |

| MYH6 | Myosin Heavy Chain 6 (Alpha-Myosin) |

| mTOR | mammalian target of rapamycin |

| MAPK | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase |

| Wnt | Wingless-Type MMTV Integration Site Family |

| JAK-STAT | Janus Kinase-Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription |

| TPM | Transcripts Per Million |

| FDR | false discovery rate |

| FC | fold change |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| LC-MS/MS | liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry |

| DIA | Data-Independent Acquisition |

| RT-qPCR | Real-time Fluorescence Quantitative PCR |

| PBS | Phosphate-Buffered Saline |

| SDS-PAGE | Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis |

| BCA | Bicinchoninic Acid Assay |

References

- Hamrick, M.W.; McGee-Lawrence, M.E.; Frechette, D.M. Fatty Infiltration of Skeletal Muscle: Mechanisms and Comparisons with Bone Marrow Adiposity. Front. Endocrinol. 2016, 7, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Xin, L.; Qing, X.; Hao, Z.; Yong, W.; Jiangjiang, Z.; Yaqiu, L. Key circRNAs from Goat: Discovery, Integrated Regulatory Network and Their Putative Roles in the Differentiation of Intramuscular Adipocytes. BMC Genom. 2023, 24, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Wang, A.; Corl, B.A.; Jiang, H. Effect of Growth Hormone on the Differentiation of Bovine Preadipocytes into Adipocytes and the Role of the Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 5b1. J. Anim. Sci. 2014, 92, 1958–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, J.; Mei, C.; Raza, S.H.A.; Khan, R.; Cheng, G.; Zan, L. SIRT5 Inhibits Bovine Preadipocyte Differentiation and Lipid Deposition by Activating AMPK and Repressing MAPK Signal Pathways. Genomics 2020, 112, 1065–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.-W.; Klemm, D.J.; Vinson, C.; Lane, M.D. Role of CREB in Transcriptional Regulation of CCAAT/Enhancer-Binding Protein β Gene during Adipogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 4471–4478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westbrook, L.; Johnson, B.J.; Gang, G.; Toyonaga, K.; Young Kang, E.; Smith, S.B. GPR120 Gene Expression and Activity in Subcutaneous and Intramuscular Adipose Tissues of Angus Crossbred Steers. J. Anim. Sci. 2023, 101, skad284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, E.D.; Hsu, C.-H.; Wang, X.; Sakai, S.; Freeman, M.W.; Gonzalez, F.J.; Spiegelman, B.M. C/EBPalpha Induces Adipogenesis through PPARgamma: A Unified Pathway. Genes Dev. 2002, 16, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Yu, S.; Guo, J.; Wang, J.; Mei, C.; Abbas Raza, S.H.; Cheng, G.; Zan, L. Comprehensive Analysis of Transcriptome and Metabolome Reveals Regulatory Mechanism of Intramuscular Fat Content in Beef Cattle. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 2911–2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewulf, J.P.; Gerin, I.; Rider, M.H.; Veiga-da-Cunha, M.; Van Schaftingen, E.; Bommer, G.T. The Synthesis of Branched-Chain Fatty Acids Is Limited by Enzymatic Decarboxylation of Ethyl- and Methylmalonyl-CoA. Biochem. J. 2019, 476, 2427–2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S.; Li, J.; Zhang, Z. Multi-Omics-Data-Assisted Genomic Feature Markers Preselection Improves the Accuracy of Genomic Prediction. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2020, 11, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahé, C.; Lavigne, R.; Com, E.; Pineau, C.; Zlotkowska, A.M.; Tsikis, G.; Mermillod, P.; Schoen, J.; Saint-Dizier, M. The Sperm-Interacting Proteome in the Bovine Isthmus and Ampulla during the Periovulatory Period. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2023, 14, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanapat, M.; Dagaew, G.; Sommai, S.; Matra, M.; Suriyapha, C.; Prachumchai, R.; Muslykhah, U.; Phupaboon, S. The Application of Omics Technologies for Understanding Tropical Plants-Based Bioactive Compounds in Ruminants: A Review. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2024, 15, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arikawa, L.M.; Mota, L.F.M.; Schmidt, P.I.; Frezarim, G.B.; Fonseca, L.F.S.; Magalhães, A.F.B.; Silva, D.A.; Carvalheiro, R.; Chardulo, L.A.L.; Albuquerque, L.G. de Genome-Wide Scans Identify Biological and Metabolic Pathways Regulating Carcass and Meat Quality Traits in Beef Cattle. Meat Sci. 2024, 209, 109402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dehghanian Reyhan, V.; Ghafouri, F.; Sadeghi, M.; Miraei-Ashtiani, S.R.; Kastelic, J.P.; Barkema, H.W.; Shirali, M. Integrated Comparative Transcriptome and circRNA-lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA ceRNA Regulatory Network Analyses Identify Molecular Mechanisms Associated with Intramuscular Fat Content in Beef Cattle. Animals 2023, 13, 2598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwanhäusser, B.; Busse, D.; Li, N.; Dittmar, G.; Schuchhardt, J.; Wolf, J.; Chen, W.; Selbach, M. Global Quantification of Mammalian Gene Expression Control. Nature 2011, 473, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Gao, H.; Fu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Song, G.; Jin, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Yin, J.; Yin, Y.; Xu, K. Comprehensive Characterization of the Differences in Metabolites, Lipids, and Volatile Flavor Compounds between Ningxiang and Berkshire Pigs Using Multi-Omics Techniques. Food Chem. 2024, 457, 139807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Bao, P.; Li, N.; Kong, S.; Wang, T.; Zhang, M.; Yu, Q.; Cao, X.; Jia, J.; Yan, P. Integrated Multi-Omics of the Longissimus Dorsal Muscle Transcriptomics and Metabolomics Reveals Intramuscular Fat Accumulation Mechanism with Diet Energy Differences in Yaks. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Wang, J.; Li, H.; Gao, L.; Geng, J.; Ma, Z.; Liu, J.; Zhang, J.; Xie, P.; Chen, L. Combined Transcriptome and Proteome Analyses Reveal Differences in the Longissimus Dorsi Muscle between Kazakh Cattle and Xinjiang Brown Cattle. Anim. Biosci. 2021, 34, 1439–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Tian, X.; Li, D.; He, Y.; Yang, P.; Cheng, Y.; Zhao, X.; Sun, J.; Yang, G. Transcriptome, Proteome and Metabolome Analysis Provide Insights on Fat Deposition and Meat Quality in Pig. Food Res. Int. 2023, 166, 112550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Xiao, Y.; Yang, F.; Liufu, S.; Gong, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhang, S.; Tang, S.; Li, B.; Ma, H. Integrated Analysis of Muscle Transcriptome, miRNA, and Proteome of Chinese Indigenous Breed Ningxiang Pig in Three Developmental Stages. Front. Genet. 2024, 15, 1393834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Fu, R.; Jin, C.; Gao, H.; Fu, B.; Li, Q.; Yu, Y.; Qi, M.; Zhang, J.; Mao, S.; et al. Multi-Omics Reveals the Mechanism of Quality Discrepancy between Gayal (Bos frontalis) and Yellow Cattle Beef. BMC Genom. 2025, 26, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Niu, Q.; Wu, T.; Su, Y.; Liu, F.; Zhao, Z.; Gao, H.; Li, J.; Xu, L. Multi-Omics Integration Analysis Reveals the Regulatory Impact of CNVs for Slaughter Traits in Cattle. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 321, 146355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, F.; Piao, M.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, S.; Wei, Z.; Liu, L.; Bu, Y.; Xu, S.; Zhao, X.; Meng, X.; et al. Multi-Omics Analysis of Transcriptomic and Metabolomics Profiles Reveal the Molecular Regulatory Network of Marbling in Early Castrated Holstein Steers. Animals 2022, 12, 3398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Ma, X.; Mei, C.; Zan, L. A Genome-Wide Landscape of mRNAs, lncRNAs, circRNAs and miRNAs during Intramuscular Adipogenesis in Cattle. BMC Genom. 2022, 23, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerquetella, M.; Pinnella, F.; Morazzini, R.; Rossi, G.; Marchegiani, A.; Gavazza, A.; Mangiaterra, S.; Di Cerbo, A.; Sorio, D.; Brandi, J.; et al. Comparative Analysis of the Fecal Proteome in Two Canine Breeds: Dalmatians and Weimaraners. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 8247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Jia, W.; Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Zheng, Q.; Shan, T. Identification of a Candidate Gene Regulating Intramuscular Fat Content in Pigs through the Integrative Analysis of Transcriptomics and Proteomics Data. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 19154–19164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Chambers, A.G.; Cecchi, F.; Hembrough, T. Targeted Data-Independent Acquisition for Mass Spectrometric Detection of RAS Mutations in Formalin-Fixed, Paraffin-Embedded Tumor Biopsies. J. Proteom. 2018, 189, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, H.L.; Roy, B.C. Meat Science and Muscle Biology Symposium: Biological Influencers of Meat Palatability: Production Factors Affecting the Contribution of Collagen to Beef Toughness1,2. J. Anim. Sci. 2019, 97, 2270–2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, H.; Magistrali, A.; Butler, G.; Stergiadis, S. Nutritional Benefits from Fatty Acids in Organic and Grass-Fed Beef. Foods 2022, 11, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gionbelli, M.P.; Costa, T.C.; Cediel-Devia, D.C.; Nascimento, K.B.; Gionbelli, T.R.S.; Duarte, M.S. Impact of Late Gestation Slow-Release Nitrogen-Enriched Diets on Energy Metabolism in Calf Skeletal Muscle: A Proteomic and Transcriptomic Approach. J. Anim. Sci. 2024, 102 (Suppl. 3), 202–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, W.; Zhang, C.; Wang, J.; Geng, X.; Qu, B.; Yue, Y.; Li, X. Fatty Acid Desaturase 2 (FADS2) Affects the Pluripotency of hESCs by Regulating Energy Metabolism. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 295, 139449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Rojas, P.; Antaramian, A.; González-Dávalos, L.; Villarroya, F.; Shimada, A.; Varela-Echavarría, A.; Mora, O. Induction of Peroxisomal Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma and Peroxisomal Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma Coactivator 1 by Unsaturated Fatty Acids, Retinoic Acid, and Carotenoids in Preadipocytes Obtained from Bovine White Adipose Tissue1,2. J. Anim. Sci. 2010, 88, 1801–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Na, S.W.; Park, S.J.; Hong, S.J.; Baik, M. Transcriptome Changes Associated with Fat Deposition in the Longissimus Thoracis of Korean Cattle Following Castration. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2020, 104, 1637–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurzov, E.N.; Stanley, W.J.; Pappas, E.G.; Thomas, H.E.; Gough, D.J. The JAK/STAT Pathway in Obesity and Diabetes. FEBS J. 2016, 283, 3002–3015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Klipfell, E.; Bennett, B.J.; Koeth, R.; Levison, B.S.; Dugar, B.; Feldstein, A.E.; Britt, E.B.; Fu, X.; Chung, Y.-M.; et al. Gut Flora Metabolism of Phosphatidylcholine Promotes Cardiovascular Disease. Nature 2011, 472, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, C.E.; Bakewell, T.; Fourcaudot, M.J.; Ayala, I.; Smelter, A.A.; Hinostroza, E.A.; Romero, G.; Asmis, M.; Freitas Lima, L.C.; Wallace, M.; et al. The Mitochondrial Pyruvate Carrier Regulates Adipose Glucose Partitioning in Female Mice. Mol. Metab. 2024, 88, 102005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Ma, C.; Xu, Y.; Chang, S.; Wu, H.; Yan, C.; Chen, J.; Wu, Y.; An, S.; Xu, J.; et al. Dynamics of the Mammalian Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Complex Revealed by In-Situ Structural Analysis. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotondo, F.; Ho-Palma, A.C.; Remesar, X.; Fernández-López, J.A.; Romero, M.D.M.; Alemany, M. Glycerol Is Synthesized and Secreted by Adipocytes to Dispose of Excess Glucose, via Glycerogenesis and Increased Acyl-Glycerol Turnover. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 8983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusminski, C.M.; Scherer, P.E. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in White Adipose Tissue. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 23, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzig, S.; Raemy, E.; Montessuit, S.; Veuthey, J.-L.; Zamboni, N.; Westermann, B.; Kunji, E.R.S.; Martinou, J.-C. Identification and Functional Expression of the Mitochondrial Pyruvate Carrier. Science 2012, 337, 93–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Li, Y.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, F.; Xu, J.; Hu, Y.; Yin, J.; Yang, K.; Sun, L.; Wang, Q.; et al. Mitochondrial Pyruvate Carrier 1 Regulates Fatty Acid Synthase Lactylation and Mediates Treatment of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Hepatology 2023, 78, 1800–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauckhorst, A.J.; Sheldon, R.D.; Pape, D.J.; Ahmed, A.; Falls-Hubert, K.C.; Merrill, R.A.; Brown, R.F.; Deshmukh, K.; Vallim, T.A.; Deja, S.; et al. A Hierarchical Hepatic de Novo Lipogenesis Substrate Supply Network Utilizing Pyruvate, Acetate, and Ketones. Cell Metab. 2025, 37, 255–273.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Li, Q.; Chen, G.; Tan, Z.; Cao, H.; Bin, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Yi, J.; Luo, X.; Tan, J.; et al. Transcriptomic Analysis Reveals a Novel Regulatory Factor of ECHDC1 Involved in Lipid Metabolism of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2022, 605, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linster, C.L.; Noël, G.; Stroobant, V.; Vertommen, D.; Vincent, M.-F.; Bommer, G.T.; Veiga-da-Cunha, M.; Van Schaftingen, E. Ethylmalonyl-CoA Decarboxylase, a New Enzyme Involved in Metabolite Proofreading. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 42992–43003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewulf, J.P.; Paquay, S.; Marbaix, E.; Achouri, Y.; Van Schaftingen, E.; Bommer, G.T. ECHDC1 Knockout Mice Accumulate Ethyl-Branched Lipids and Excrete Abnormal Intermediates of Branched-Chain Fatty Acid Metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 297, 101083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althaher, A.R. An Overview of Hormone-Sensitive Lipase (HSL). Sci. World J. 2022, 2022, 1964684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name | Sense Sequence (5′-3′) | Antisense Sequence (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|

| si-NC | UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT | ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAATT |

| si-ECHDC1 | GCAUGUGAUUUCAGGUUAATT | UUAACCUGAAAUCACAUGCTT |

| Genes | Primer Sequence | Annealing Temperature | NCBI RefSeq Accession |

|---|---|---|---|

| 18S | F: CCTGCGGCTTAATTTGACTC | 61 °C | NR_036642.1 |

| R: AACTAAGAACGGCCATGCAC | |||

| ECHDC1 | F: ATCATCGGCGGTAGACAAGC | 61 °C | / |

| R: TGGTCCACCCCAAACTGTTC | |||

| PPARγ | F: TGAAGAGCCTTCCAACTCCC | 61 °C | NM_181024.2 |

| R: GTCCTCCGGAAGAAACCCTTG | |||

| C/EBPα | F: ATCTGCGAACACGAGACG | 61 °C | NM_176784.2 |

| R: CCAGGAACTCGTCGTTGAA | |||

| HSL | F: GATGAGAGGGTAATTGCCG | 61 °C | NM_001080220.1 |

| R: GGATGGCAGGTGTGAACT | |||

| ATGL | F: TGCTGATTGCTATGAGTGTGCC | 61 °C | NM_001046005.2 |

| R: CCTCTTTGGAGTTGAAGTGGGT | |||

| FABP4 | F: GCTGCACTTCTTTCTCACCTTG | 61 °C | NM_174314.2 |

| R: ACCACACCCCCATTCAAACT | |||

| ACACA | F: CTCCAACCTCAACCACTACGG | 61 °C | NM_174224.2 |

| R: GGGGAATCACAGAAGCAGCC |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

He, R.; Liu, L.; Kong, X.; Wang, N.; Tan, J.; Wu, Z.; Zan, L.; Yang, W. Integrated Transcriptomic and Proteomic Analysis Associated with Knockdown and Overexpression Studies Revealed ECHDC1 as a Regulator of Intramuscular Fat Deposition in Cattle. Animals 2025, 15, 3558. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243558

He R, Liu L, Kong X, Wang N, Tan J, Wu Z, Zan L, Yang W. Integrated Transcriptomic and Proteomic Analysis Associated with Knockdown and Overexpression Studies Revealed ECHDC1 as a Regulator of Intramuscular Fat Deposition in Cattle. Animals. 2025; 15(24):3558. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243558

Chicago/Turabian StyleHe, Ruiying, Li Liu, Xianya Kong, Nanfei Wang, Jianbing Tan, Zhangqing Wu, Linsen Zan, and Wucai Yang. 2025. "Integrated Transcriptomic and Proteomic Analysis Associated with Knockdown and Overexpression Studies Revealed ECHDC1 as a Regulator of Intramuscular Fat Deposition in Cattle" Animals 15, no. 24: 3558. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243558

APA StyleHe, R., Liu, L., Kong, X., Wang, N., Tan, J., Wu, Z., Zan, L., & Yang, W. (2025). Integrated Transcriptomic and Proteomic Analysis Associated with Knockdown and Overexpression Studies Revealed ECHDC1 as a Regulator of Intramuscular Fat Deposition in Cattle. Animals, 15(24), 3558. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243558