Effect of Stocking Density and Biofilm-Based Microalgae on Larvae and Post-Larvae Growth and Settlement Patterns of the Clam Ruditapes decussatus (Linnaeus, 1758) in Captivity

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Clam Sampling and Broodstock Conditioning

2.2. Spawning and Fertilization

2.3. Larval Rearing and Post-Larvae Settlement

2.4. Algal Biofilms and Post-Larvae Settlement

2.4.1. Preparation of Algal Biofilms and Settlement Rearing

2.4.2. Spat Grading

2.5. Feeding Process

2.6. Statistical Analyses of Data

3. Results

3.1. Effect of Stocking Density on Larval Rearing

3.2. Effect of Stocking Density on Settlement

3.3. Effect of Biofilm on Post-Settlement Performance

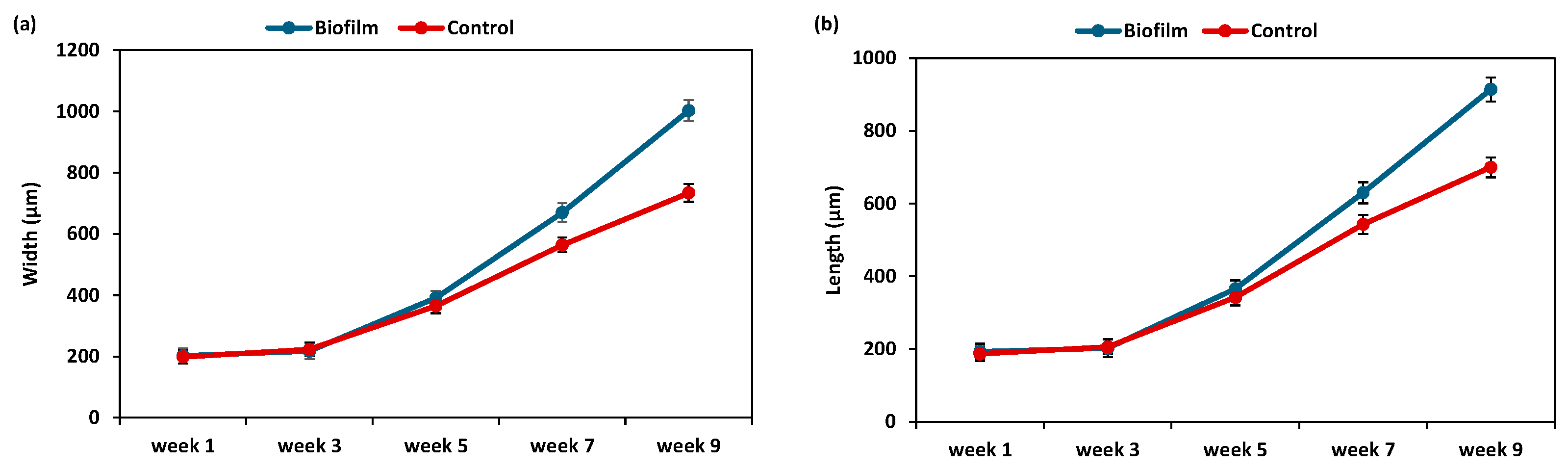

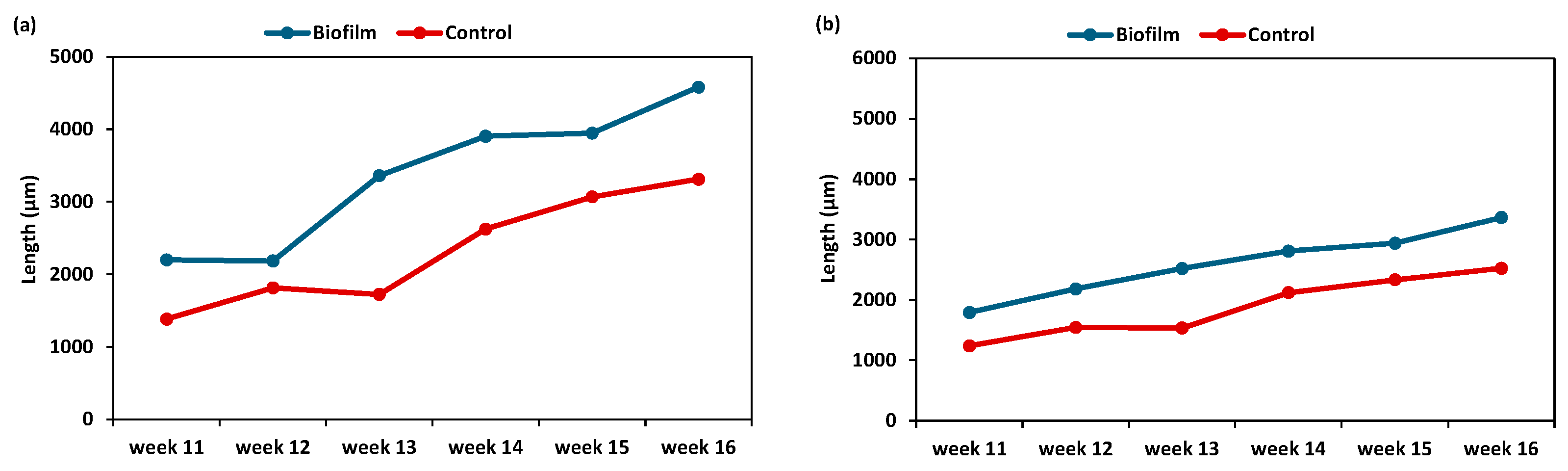

3.3.1. Effect of Biofilms on Post-Larvae Performance

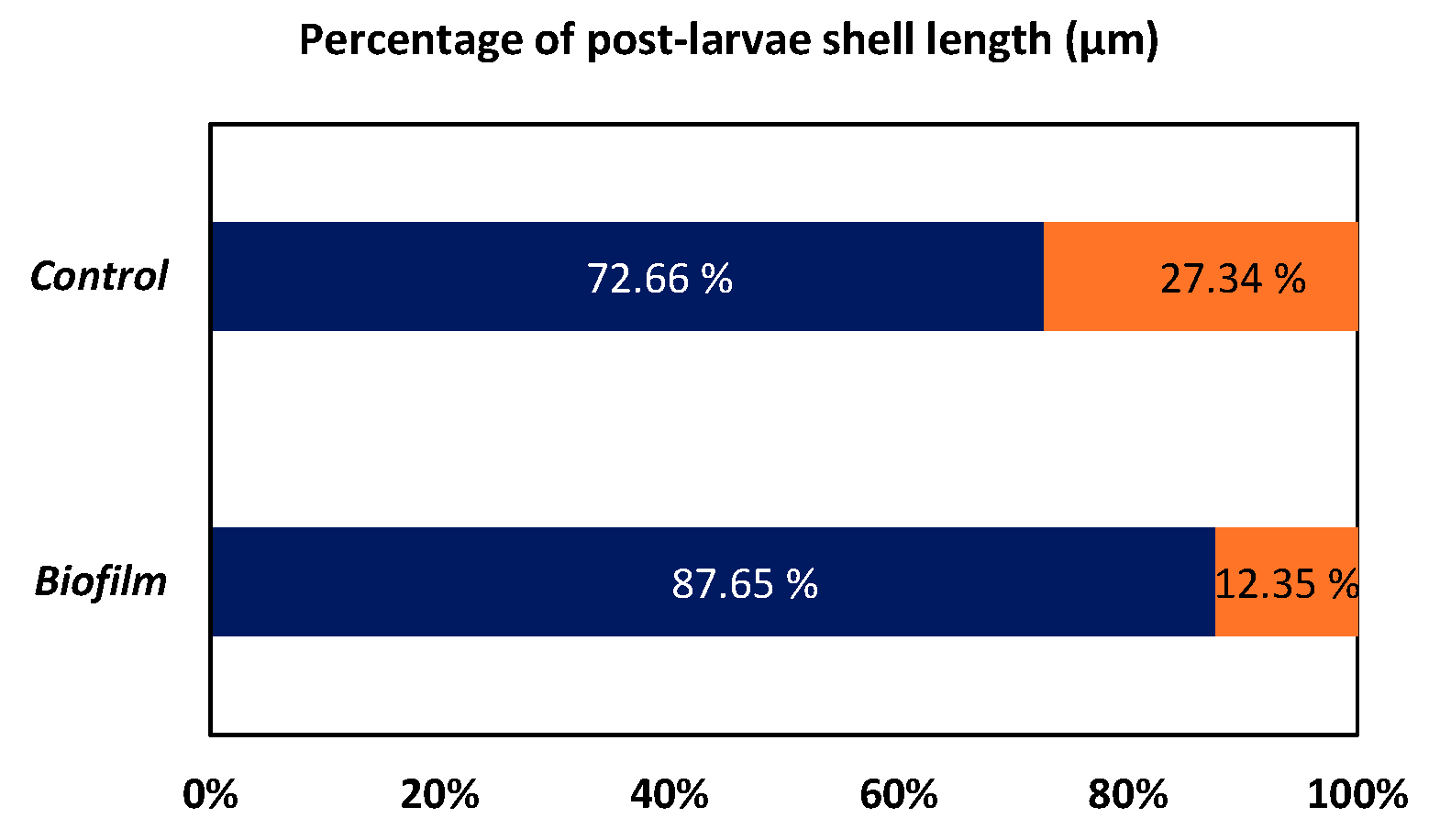

3.3.2. Effect of Biofilms on Spat Size

Effect on Spat Shell Length Classes

Shell Length Classes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Matias, D.; Joaquim, S.; Leitão, A.; Massapina, C. Effect of Geographic Origin, Temperature and Timing of Broodstock Collection on Conditioning, Spawning Success and Larval Viability of Ruditapes decussatus (Linné, 1758). Aquac. Int. 2009, 17, 257–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matias, D.; Joaquim, S.; Matias, A.M.; Moura, P.; de Sousa, J.T.; Sobral, P.; Leitão, A. The Reproductive Cycle of the European Clam Ruditapes decussatus (L., 1758) in Two Portuguese Populations: Implications for Management and Aquaculture Programs. Aquaculture 2013, 406, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azirar, R.; Fettach, S.; da Costa, F.; Pérez, M.; Chiaar, A.; Aghzar, A.; Ouagajjou, Y. Effects of geographical origin and timing of broodstock collection on hatchery conditioning of the clam Ruditapes decussatus (L. 1758). Animals 2024, 15, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saavedra, C.; Cordero, D. Genetic variability and genetic differentiation of populations in the grooved carpet shell clam (Ruditapes decussatus) based on intron polymorphisms. Oceans 2024, 5, 257–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medlouh, M.; Doukilo, I.; Errhif, A.; Idhalla, M. Development of a new rearing technique for the clam Ruditapes decussatus (Linnaeus, 1758) and evaluation of its zootechnical performance in the Oualidia Lagoon, Morocco. Aquac. Aquar. Conserv. Legis. 2023, 16, 1231–1244. [Google Scholar]

- Kamara, A.; Rharbi, N.; Berraho, A.; Idhalla, M.; Ramdani, M. Comparative Study of Sexual Cycle of the European Clam Ruditapes decussatus from Three Paralic Sites off the Moroccan Coast. Mar. Life 2005, 15, 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Belbachir, C.; Chafi, A.; Aouniti, A.; Khamri, M. Qualité Microbiologique de Trois Espèces de Mollusques Bivalves à Intérêt Commercial Récoltées sur la Côte Méditerranéenne Nord-Est du Maroc (Microbiological Quality of Three Bivalve Mollusks Species with Commercial Interest Collected on the North-Eastern Coast of Morocco). J. Mater. Environ. Sci. 2014, 5, 304–309. [Google Scholar]

- Macho, G.; Woodin, S.A.; Wethey, D.S.; Vázquez, E. Impacts of Sublethal and Lethal High Temperatures on Clams Exploited in European Fisheries. J. Shellfish Res. 2016, 35, 405–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranguren, R.; Gomez-León, J.; Balseiro, P.; Costa, M.M.; Novoa, B.; Figueras, A. Abnormal Mortalities of the Carpet Shell Clam Ruditapes decussatus (Linnaeus, 1758) in Natural Bed Populations: A Practical Approach. Aquac. Res. 2014, 45, 1303–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidegain, G.; Bárcena, J.F.; García, A.; Juanes, J.A. Predicting Coexistence and Predominance Patterns between the Introduced Manila Clam (Ruditapes philippinarum) and the European Native Clam (Ruditapes decussatus). Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2015, 152, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helm, M.M.; Bourne, N.; Lovatelli, A. The Hatchery Culture of Bivalves: A Practical Manual; FAO Fisheries Technical Paper No. 471; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2004; Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/handle/20.500.14283/y5720e (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Azirar, R.; Janah, H.; Aghzar, A.; Ouagajjou, Y. Effect of Stocking Density on Larval Performance and Post-Larvae Settlement of Clam Ruditapes decussatus (Linnaeus, 1758) in Bivalve Hatchery Production. E3S Web Conf. 2024, 492, 02002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janah, H.; Azirar, R.; Aghzar, A.; Ouagajjou, Y. Effect of Food Strategy and Stocking Density on Larval Performance of Captively Reared Mytilus galloprovincialis. E3S Web Conf. 2024, 492, 02001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa, F.; Cerviño-Otero, A.; Iglesias, Ó.; Cruz, A.; Guévélou, E. Hatchery Culture of European Clam Species (Family Veneridae). Aquac. Int. 2020, 28, 1675–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, W.Y.; Satuito, C.G.; Yang, J.L.; Kitamura, H. Larval settlement and metamorphosis of the mussel Mytilus galloprovincialis in response to biofilms. Mar. Biol. 2007, 150, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Lu, X.; Lu, H. Marine Microbial Biofilms on Diverse Abiotic Surfaces. Front. Mar. Sci. 2025, 12, 1482946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.L.; Li, X.; Liang, X.; Bao, W.Y.; Shen, H.D.; Li, J.L. Effects of natural biofilms on settlement of plantigrades of the mussel Mytilus coruscus. Aquaculture 2014, 424, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadfield, M.G.; Paul, V.J. Natural Chemical Cues for Settlement and Metamorphosis of Marine Invertebrate Larvae. In Marine Chemical Ecology; McClintock, J.B., Baker, B.J., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2001; pp. 431–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; He, W.; Li, H.; Yan, Y.; Lin, C. Larval settlement and metamorphosis of the pearl oyster Pinctada fucata in response to biofilms. Aquaculture 2010, 306, 334–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, A.H.; Meritt, D.W.; Franklin, R.B.; Boone, E.L.; Nicely, C.T.; Brown, B.L. Effects of age and composition of field-produced biofilms on oyster larval setting. Biofouling 2011, 27, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitz, T.; Wagner, T. The Marine Bacterium Alteromonas espejiana Induces Metamorphosis of the Hydroid Hydractinia echinata. Mar. Biol. 1993, 115, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satuito, C.G.; Shimizu, K.; Fusetani, N. Studies on the Factors Influencing Larval Settlement in Balanus amphitrite and Mytilus galloprovincialis. Hydrobiologia 1997, 358, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zardus, J.D.; Nedved, B.T.; Huang, Y.; Tran, C.; Hadfield, M.G. Microbial biofilms facilitate adhesion in biofouling invertebrates. Biol. Bull. 2008, 214, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Colen, C.; Lenoir, J.; De Backer, A.; Vanelslander, B.; Vincx, M.; Degraer, S.; Ysebaert, T. Settlement of Macoma balthica Larvae in Response to Benthic Diatom Films. Mar. Biol. 2009, 156, 2161–2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobretsov, S.; Rittschof, D. Love at First Taste: Induction of Larval Settlement by Marine Microbes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Bao, W.Y.; Gu, Z.Q.; Li, Y.F.; Liang, X.; Ling, Y.; Yang, J.L. Larval Settlement and Metamorphosis of the Mussel Mytilus coruscus in Response to Natural Biofilms. Biofouling 2012, 28, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toupoint, N.; Mohit, V.; Linossier, I.; Bourgougnon, N.; Myrand, B.; Olivier, F.; Tremblay, R. Effect of Biofilm Age on Settlement of Mytilus edulis. Biofouling 2012, 28, 985–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gribben, P.E.; Wright, J.T.; O’Connor, W.A.; Steinberg, P. Larval Settlement Preference of a Native Bivalve: The Influence of an Invasive Alga versus Native Substrata. Aquat. Biol. 2009, 7, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobretsov, S.V. Effects of Macroalgae and Biofilm on Settlement of Blue Mussel (Mytilus edulis L.) Larvae. Biofouling 1999, 14, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokal, R.R.; Rohlf, F.J. Biometry: The Principles and Practice of Statistics in Biological Research, 4th ed.; W.H. Freeman: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.; Dong, B.; Tang, B.; Zhang, T.; Xiang, J. Effect of stocking density on growth, settlement and survival of clam larvae, Meretrix meretrix. Aquaculture 2006, 258, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Zhang, G.; Yang, F. Effects of diet, stocking density, and environmental factors on growth, survival, and metamorphosis of Manila clam Ruditapes philippinarum larvae. Aquaculture 2006, 253, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, D.; Abarca, A.; Gutiérrez, R.; Herrera, L.; Celis, Á.; Durán, L.R. Effect of stocking density and food ration on growth and survival of veliger and pediveliger larvae of the taquilla clam Mulinia edulis reared in the laboratory. Rev. Biol. Mar. Oceanogr. 2014, 49, 567–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doroudi, M.S.; Southgate, P.C. The Influence of Algal Ration and Larval Density on Growth and Survival of Blacklip Pearl Oyster Pinctada margaritifera (L.) Larvae. Aquac. Res. 2000, 31, 621–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, P.C.M.D.; Lavander, H.D.; Silva, L.O.B.D.; Gálvez, A.O. Larviculture of the Sand Clam Cultivated in Different Densities. Bol. Inst. Pesca 2018, 44, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- His, E.; Seaman, M.N.L. Effects of Temporary Starvation on the Survival, and on Subsequent Feeding and Growth, of Oyster (Crassostrea gigas) Larvae. Mar. Biol. 1992, 114, 277–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, R.; McKinley, S.; Pearce, C.M. Effects of Nutrition on Larval Growth and Survival in Bivalves. Rev. Aquac. 2010, 2, 33–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Costa, F.; Nóvoa, S.; Ojea, J.; Martínez-Patiño, D. Effects of Algal Diets and Starvation on Growth, Survival and Fatty Acid Composition of Solen marginatus (Bivalvia: Solenidae) Larvae. Sci. Mar. 2012, 76, 527–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janah, H.; Aghzar, A.; Presa, P.; Ouagajjou, Y. Influence of Pediveliger Larvae Stocking Density on Settlement Efficiency and Seed Production in Captivity of Mytilus galloprovincialis in Amsa Bay, Tetouan. Animals 2024, 14, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, S.M.; Mann, R. Effects of Hypoxia and Anoxia on Larval Settlement, Juvenile Growth, and Juvenile Survival of the Oyster Crassostrea virginica. Biol. Bull. 1992, 182, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- His, E.; Robert, R.; Dinet, A. Combined Effects of Temperature and Salinity on Fed and Starved Larvae of the Mediterranean Mussel Mytilus galloprovincialis and the Japanese Oyster Crassostrea gigas. Mar. Biol. 1989, 100, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawlor, J.A.; Arellano, S.M. Temperature and Salinity, Not Acidification, Predict Near-Future Larval Growth and Larval Habitat Suitability of Olympia Oysters in the Salish Sea. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 13787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmani, K.; Petton, B.; Le Grand, J.; Mounier, J.; Robert, R.; Nicolas, J.L. Determination of Stocking Density Limits for Crassostrea gigas Larvae Reared in Flow-Through and Recirculating Aquaculture Systems and Interaction between Larval Density and Biofilm Formation. Aquat. Living Resour. 2017, 30, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turini, C.S.; Sühnel, S.; Lagreze-Squella, F.J.; Ferreira, J.F.; Melo, C.M.R.D. Effects of Stocking-Density in Flow-Through System on the Mussel Perna perna Larval Survival. Acta Sci. Anim. Sci. 2014, 36, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Wang, H.; Li, M.; Teng, M.; Wang, X.; Zhao, A.; Bao, Z. Optimizing Microalgae Diet, Temperature, and Salinity for Dwarf Surf Clam, Mulinia lateralis, Spat Culture. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 8, 823112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamburri, M.N.; Luckenbach, M.W.; Breitburg, D.L.; Bonniwell, S.M. Settlement of Crassostrea ariakensis Larvae: Effects of Substrate, Biofilms, Sediment and Adult Chemical Cues. J. Shellfish Res. 2008, 27, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cima, F. Larval Settlement on Marine Surfaces: The Role of Physico-Chemical Interactions. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hird, C.; Jékely, G.; Williams, E.A. Microalgal Biofilm Induces Larval Settlement in the Model Marine Worm Platynereis dumerilii. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2024, 11, 240274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albentosa, M.; Pérez-Camacho, A.; Labarta, U.; Beiras, R.; Fernández-Reiriz, M.J. Nutritional Value of Algal Diets to Clam Spat Venerupis pullastra. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1993, 97, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Camacho, A.; Beiras, R.; Albentosa, M. Effects of Algal Food Concentration and Body Size on the Ingestion Rates of Ruditapes decussatus (Bivalvia) Veliger Larvae. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1994, 115, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Larval Stage/Feeding | Microalgae Species | Percentage (by Cell Count) | Cell Density (Cells µL−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early larvae (Day 2–8) | I. galbana | ≈55% | 20, gradually increased to 50 |

| C. calcitrans | ≈45% | 25–30, gradually increased to 60 | |

| Late larvae (Day 9–16) | I. galbana | 50% | 50–75 |

| C. calcitrans | 40% | 50–75 | |

| T. suecica | 10% | 10–15 | |

| Post-larvae (settlement) | I. galbana, C. calcitrans, T. suecica | 100% (mixture) | 100–150 |

| Initial Density (larvae mL−1) | Length (µm) | Survival (Normalized Values) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean +/− SD | Df Factor | Df Residual | F | p-Value | Mean +/− SD | Df Factor | Df Residual | F | p-Value | |

| D10 | 220.81 ± 2.39 | 2 | 6 | 18.47 | 2.4 × 10−2 * | 15.76 ± 2.19 | 2 | 6 | 13.67 | 3.2 × 10−2 * |

| D20 | 217.48 ± 3.19 | 12.83 ± 2.28 | ||||||||

| D40 | 200.65 ± 2.92 | 9.59 ± 1.82 | ||||||||

| Density | D10 | D20 | D40 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survival | D10 | - | 0.088 ns | 0.037 * |

| D20 | - | 0.073 ns | ||

| D40 | - | |||

| Length | D10 | - | 0.074 ns | 0.041 * |

| D20 | - | 0.065 ns | ||

| D40 | - |

| Di | Settlement Rate (%) | Spat Yield (Spat.cm−2) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean +/− SD | Df (Factor; Residual) | F | p-Value | Mean +/− SD | Df (Factor; Residual) | F | p-Value | |

| D35 | 35.85 ± 10.23 | 3; 8 | 14.88 | 2.4 × 10−4 *** | 13.23 ± 2.65 | 3; 8 | 13.09 | 3.1 × 10−4 *** |

| D70 | 33.35 ± 7.35 | 23.82 ± 5.25 | ||||||

| D100 | 17.77 ± 1.67 | 19.04 ± 1.79 | ||||||

| D140 | 9.38 ± 5.26 | 9.29 ± 3.42 | ||||||

| Density | D35 | D70 | D100 | D140 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Settlement (%) | D35 | - | 0.091 ns | 0.034 * | 0.024 * |

| D70 | - | 0.041 * | 0.021 * | ||

| D100 | - | 0.038 * | |||

| D140 | - | ||||

| Spat yield | D35 | - | 0.035 * | 0.041 * | 0.086 ns |

| D70 | - | 0.072 ns | 0.032 * | ||

| D100 | - | 0.037 * | |||

| D140 | - |

| Week 1 | Week 3 | Week 5 | Week 7 | Week 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Width | F = 1.675 ns | F = 1.453 ns | F = 17.34 * | F = 14.24 ** | F = 13.28 ** |

| Length | F = 1.653 ns | F = 1.458 ns | F = 15.43 * | F = 12.41 ** | F = 12.98 ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Azirar, R.; Ouagajjou, Y.; da Costa, F.; Janah, H.; Aghzar, A. Effect of Stocking Density and Biofilm-Based Microalgae on Larvae and Post-Larvae Growth and Settlement Patterns of the Clam Ruditapes decussatus (Linnaeus, 1758) in Captivity. Animals 2025, 15, 3557. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243557

Azirar R, Ouagajjou Y, da Costa F, Janah H, Aghzar A. Effect of Stocking Density and Biofilm-Based Microalgae on Larvae and Post-Larvae Growth and Settlement Patterns of the Clam Ruditapes decussatus (Linnaeus, 1758) in Captivity. Animals. 2025; 15(24):3557. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243557

Chicago/Turabian StyleAzirar, Rania, Yassine Ouagajjou, Fiz da Costa, Hafsa Janah, and Adil Aghzar. 2025. "Effect of Stocking Density and Biofilm-Based Microalgae on Larvae and Post-Larvae Growth and Settlement Patterns of the Clam Ruditapes decussatus (Linnaeus, 1758) in Captivity" Animals 15, no. 24: 3557. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243557

APA StyleAzirar, R., Ouagajjou, Y., da Costa, F., Janah, H., & Aghzar, A. (2025). Effect of Stocking Density and Biofilm-Based Microalgae on Larvae and Post-Larvae Growth and Settlement Patterns of the Clam Ruditapes decussatus (Linnaeus, 1758) in Captivity. Animals, 15(24), 3557. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243557