The Effects of Eyestalk Ablation on the Androgenic Gland and the Male Reproductive Organs in the Kuruma Prawn Marsupenaeus japonicus

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design

2.2. Sample Collection

2.3. Biometric Indices

2.4. Total RNA Extraction, Reverse Transcription, and Quantitative Real-Time PCR

2.5. Histology of the Male Reproductive Organs

2.6. Measurement of AG Area

2.7. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Effects of ESA on Somatic Growth and the Development of Male Reproductive Organ

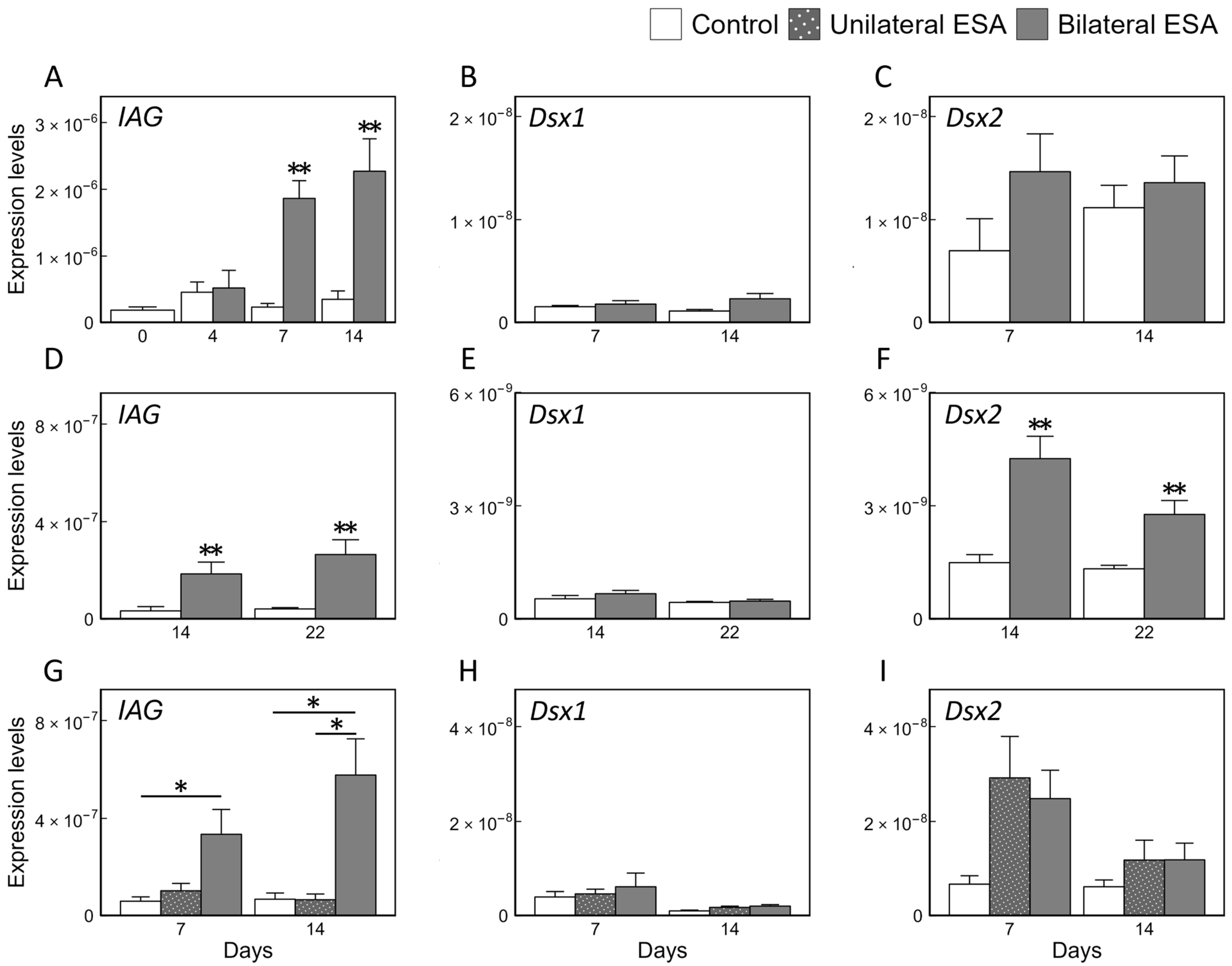

3.2. Effects of ESA on Relative Expression Levels of Maj-IAG, Maj-Dsx1, and Maj-Dsx2 in SV

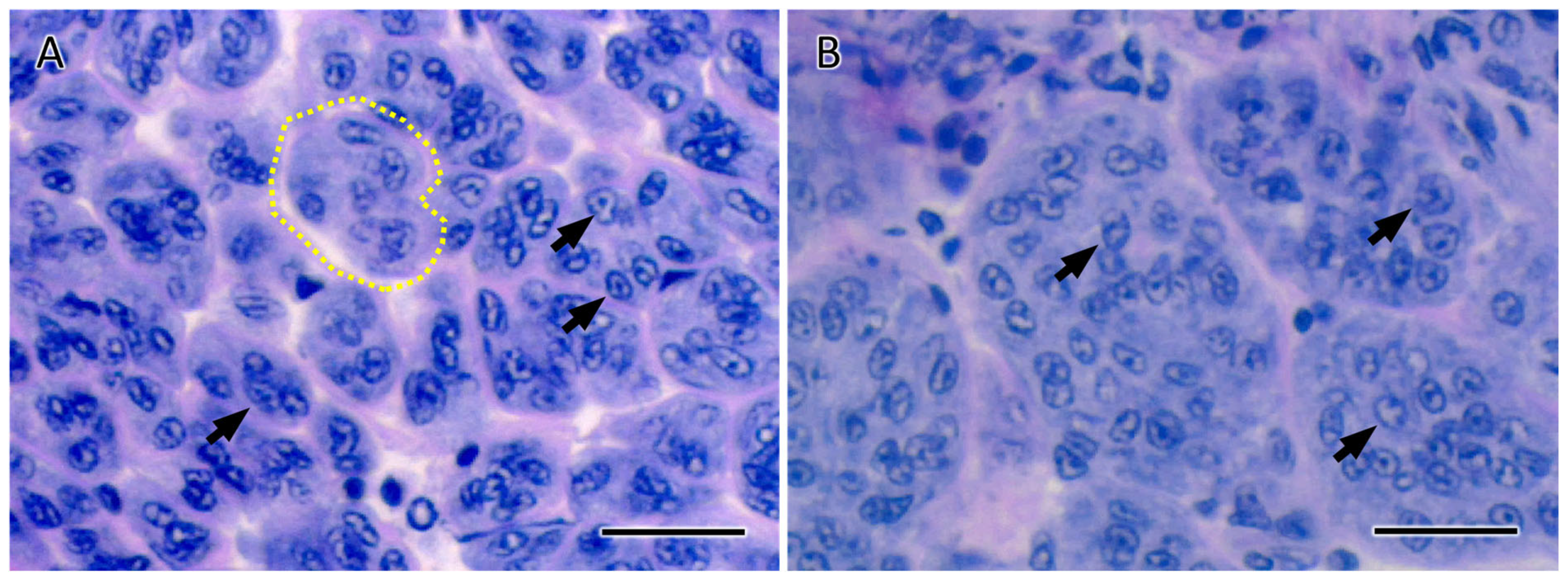

3.3. ESA Effects on AG Area and Spermatogenesis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Charniaux-Cotton, H. Découverte Chez Un Crustacé Amphipode (Orchestia gammarella) d’une Glande Endocrine Responsable de La Différenciation Des Caractéres Sexuels Primaires et Secondaires Mâles. C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris 1954, 239, 780–782. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Katakura, Y. Hormonal Control of Development of Sexual Characters in the Isopod Crustacean, Armadillidium vulgare. Annot. Zool. Japon. 1961, 2, 60–71. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, G.; Sorokine, O.; Moniatte, M.; Bulet, P.; Hetru, C.; Van Dorsselaer, A. The Structure of a Glycosylated Protein Hormone Responsible for Sex Determination in the Isopod, Armadillidium vulgare. Eur. J. Biochem. 1999, 262, 727–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagamine, C.; Knight, A.W.; Maggenti, A.; Paxman, G. Effects of Androgenic Gland Ablation on Male Primary and Secondary Sexual Characteristics in the Malaysian Prawn, Macrobrachium rosenbergii (de Man) (Decapoda, Palaemonidae), with First Evidence of Induced Feminization in a Nonhermaphroditic Decapod. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 1980, 41, 423–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalaila, I.; Katz, T.; Abdu, U.; Yehezkel, G.; Sagi, A. Effects of Implantation of Hypertrophied Androgenic Glands on Sexual Characters and Physiology of the Reproductive System in the Female Red Claw Crayfish, Cherax quadricarinatus. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2001, 121, 242–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagamine, C.; Knight, A.W.; Maggenti, A.; Paxman, G. Masculinization of Female Macrobrachium rosenbergii (de Man) (Decapoda, Palaemonidae) by Androgenic Gland Implantation. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 1980, 41, 442–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malecha, S.R.; Nevin, P.A.; Ha, P.; Barck, L.E.; Lamadrid-Rose, Y.; Masuno, S.; Hedgecock, D. Sex-Ratios and Sex-Determination in Progeny from Crosses of Surgically Sex-Reversed Freshwater Prawns, Macrobrachium rosenbergii. Aquaculture 1992, 105, 201–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manor, R.; Weil, S.; Oren, S.; Glazer, L.; Aflalo, E.D.; Ventura, T.; Chalifa-Caspi, V.; Lapidot, M.; Sagi, A. Insulin and Gender: An Insulin-like Gene Expressed Exclusively in the Androgenic Gland of the Male Crayfish. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2007, 150, 326–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, C.; Li, F.; Wang, L.; Wu, F.; Wang, J.; Fan, X.; Liu, T. Molecular Characteristics and Abundance of Insulin-like Androgenic Gland Hormone and Effects of RNA Interference in Eriocheir sinensis. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2020, 215, 106332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosen, O.; Manor, R.; Weil, S.; Gafni, O.; Linial, A.; Aflalo, E.D.; Ventura, T.; Sagi, A. A Sexual Shift Induced by Silencing of a Single Insulin-like Gene in Crayfish: Ovarian Upregulation and Testicular Degeneration. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e15281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ventura, T.; Manor, R.; Aflalo, E.D.; Weil, S.; Rosen, O.; Sagi, A. Timing Sexual Differentiation: Full Functional Sex Reversal Achieved through Silencing of a Single Insulin-like Gene in the Prawn, Macrobrachium rosenbergii. Biol. Reprod. 2012, 86, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura, T.; Manor, R.; Aflalo, E.D.; Weil, S.; Raviv, S.; Glazer, L.; Sagi, A. Temporal Silencing of an Androgenic Gland-Specific Insulin-like Gene Affecting Phenotypical Gender Differences and Spermatogenesis. Endocrinology 2009, 150, 1278–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, T.; Sagi, A. The “IAG-Switch”—A Key Controlling Element in Decapod Crustacean Sex Differentiation. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, J.S.; Manor, R.; Sagi, A. Cloning of an Insulin-like Androgenic Gland Factor (IAG) from the Blue Crab, Callinectes sapidus: Implications for Eyestalk Regulation of IAG Expression. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2011, 173, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Fu, Y.; Hu, Y.; Fu, H.; Jiang, S.; Xiong, Y.; Qiao, H.; Zhang, W.; Gong, Y.; Wu, Y. Identification of Candidate Genes from Androgenic Gland in Macrobrachium nipponense Regulated by Eyestalk Ablation. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 19855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Islas, G.; Guerrero-Tortolero, D.A.; Garza-Torres, R.; Álvarez-Ruiz, P.; Mejía-Ruiz, H.; Campos-Ramos, R. Quantitative Analysis of Hypertrophy and Hyperactivity in the Androgenic Gland of Eyestalk-Ablated Male Pacific White Shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei during Molt Stages. Aquaculture 2015, 439, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Wang, W.; Wang, C.; Sun, C.; Shi, L.; Chan, S.F. Insulin-like Androgenic Gland Hormone from the Shrimp Fenneropenaeus merguiensis: Expression, Gene Organization and Transcript Variants. Gene 2021, 782, 145529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okumura, T.; Nikaido, H.; Yoshida, K.; Kotaniguchi, M.; Tsuno, Y.; Seto, Y.; Watanabe, T. Changes in Gonadal Development, Androgenic Gland Cell Structure, and Hemolymph Vitellogenin Levels during Male Phase and Sex Change in Laboratory-Maintained Protandric Shrimp, Pandalus hypsinotus (Crustacea: Caridea: Pandalidae). Mar. Biol. 2005, 148, 347–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalaila, I.; Manor, R.; Weil, S.; Granot, Y.; Keller, R.; Sagi, A. The Eyestalk-Androgenic Gland-Testis Endocrine Axis in the Crayfish Cherax quadricarinatus. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2002, 127, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sroyraya, M.; Chotwiwatthanakun, C.; Stewart, M.J.; Soonklang, N.; Kornthong, N.; Phoungpetchara, I.; Hanna, P.J.; Sobhon, P. Bilateral Eyestalk Ablation of the Blue Swimmer Crab, Portunus pelagicus, Produces Hypertrophy of the Androgenic Gland and an Increase of Cells Producing Insulin-like Androgenic Gland Hormone. Tissue Cell 2010, 42, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payen, G.; Costlow, J.D.; Charniaux-Cotton, H. Etude comparative de l’ultrastructure des glandes androgènes de Crabes normaux et pédonculectomisés pendant la vie larvaire ou après la puberté chez les espèces: Rhithropanopeus harrisii (Gould) et Callinectes sapidus Rathbun. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 1971, 17, 526–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, R. Crustacean Neuropeptides: Structures, Functions and Comparative Aspects. Experientia 1992, 48, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Li, S.; Lv, X.; Xiang, J.; Manor, R.; Sagi, A.; Li, F. Sex-Biased CHHs and Their Putative Receptor Regulate the Expression of IAG Gene in the Shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Lu, Z.; Qin, Z.; Yang, G.; Sarath Babu, V.; Zhang, M.; Xu, Z.; Zhao, L.; Pan, G.; Lin, L. Examination of the Potential Role of CHH in Regulating the Expression of IAGBP Gene through the Eyestalk-Testis Pathway. Aquaculture 2022, 547, 737455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.; Liu, J.; Liu, F.; Huang, Y.; Wang, G.; Ye, H. Crustacean Female Sex Hormone from the Mud Crab Scylla paramamosain Is Highly Expressed in Prepubertal Males and Inhibits the Development of Androgenic Gland. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Bai, H.; Zhang, W.; Fu, H.; Jiang, F.; Liang, G.; Jin, S.; Sun, S.; Qiao, H. Cloning of Genomic Sequences of Three Crustacean Hyperglycemic Hormone Superfamily Genes and Elucidation of Their Roles of Regulating Insulin-like Androgenic Gland Hormone Gene. Gene 2015, 561, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Liu, Z.Q.; Ma, K.Y.; Tao, J.R.; Fang, X.; Qiu, G.F. A Testis-Specific Gene Doublesex Is Involved in Spermatogenesis and Early Sex Differentiation of the Chinese Mitten Crab Eriocheir sinensis. Aquaculture 2023, 569, 739401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.Y.; Huang, J.H.; Zhou, F.L.; Yang, Q.B.; Li, Y.D.; Jiang, S.; Jiang, S.G.; Yang, L.S. Identification and Expression Analysis of Dsx and Its Positive Transcriptional Regulation of IAG in Black Tiger Shrimp (Penaeus monodon). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Li, F.; Yu, K.; Xiang, J. Identification and Characterization of a Doublesex Gene Which Regulates the Expression of Insulin-like Androgenic Gland Hormone in Fenneropenaeus chinensis. Gene 2018, 649, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banzai, K.; Ishizaka, N.; Asahina, K.; Suitoh, K.; Izumi, S.; Ohira, T. Molecular Cloning of a cDNA Encoding Insulin-like Androgenic Gland Factor from the Kuruma Prawn Marsupenaeus japonicus and Analysis of Its Expression. Fish. Sci. 2011, 77, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furukawa, T.; Yamane, F.; Takeuchi, R.; Ohira, T.; Toyota, K.; Miyazaki, T.; Tsutsui, N. Insulin-like Androgenic Gland Factor Regulates the Development of Internal and External Secondary Sexual Characteristics in Juvenile Male Kuruma Prawn Marsupenaeus japonicus. Aquac. Rep. 2025, 45, 103086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyota, K.; Mekuchi, M.; Akashi, H.; Miyagawa, S.; Ohira, T. Sexual Dimorphic Eyestalk Transcriptome of Kuruma Prawn Marsupenaeus japonicus. Gene 2023, 885, 147700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsutsui, N.; Yamane, F.; Kakinuma, M.; Yoshimatsu, T. Multiple Insulin-like Peptides in the Gonads of the Kuruma Prawn Marsupenaeus japonicus. Fish. Sci. 2022, 88, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindelin, J.; Arganda-Carreras, I.; Frise, E.; Kaynig, V.; Longair, M.; Pietzsch, T.; Preibisch, S.; Rueden, C.; Saalfeld, S.; Schmid, B.; et al. Fiji: An Open-Source Platform for Biological-Image Analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C.A.; Rasband, W.S.; Eliceiri, K.W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 Years of Image Analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Zheng, H.; Zheng, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, M.; Xie, X.; Zhu, D. Molecular Characterization of the Insulin-Like Androgenic Gland Hormone in the Swimming Crab, Portunus trituberculatus, and Its Involvement in the Insulin Signaling System. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, A.; Green, S.; Wang, T.; Bachvaroff, T.; Chung, J.S. Seasonal Changes in the Expression of Insulinlike Androgenic Hormone (IAG) in the Androgenic Gland of the Jonah Crab, Cancer borealis. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0261206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yano, I. Induction of Rapid Spawning in Kuruma Prawn, Penaeus japonicus, through Unilateral Eyestalk Enucleation. Aquaculture 1984, 40, 265–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumura, T. Effects of Bilateral and Unilateral Eyestalk Ablation on Vitellogenin Synthesis in Immature Female Kuruma Prawns, Marsupenaeus japonicus. Zool. Sci. 2007, 24, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burtis, K.C.; Baker, B.S. Drosophila Doublesex Gene Controls Somatic Sexual Differentiation by Producing Alternatively Spliced mRNAs Encoding Related Sex-Specific Polypeptides. Cell 1989, 56, 997–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rideout, E.J.; Dornan, A.J.; Neville, M.C.; Eadie, S.; Goodwin, S.F. Control of Sexual Differentiation and Behavior by the Doublesex Gene in Drosophila melanogaster. Nat. Neurosci. 2010, 13, 458–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coschigano, K.T.; Wensink, P.C. Sex-Specific Transcriptional Regulation by the Male and Female Doublesex Proteins of Drosophila. Genes Dev. 1993, 7, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz, M.F.; Alvarez, M.; Eirín-López, J.M.; Sarno, F.; Kremer, L.; Barbero, J.L.; Sánchez, L. An Unusual Role for Doublesex in Sex Determination in the Dipteran Sciara. Genetics 2015, 200, 1181–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, M.G.; Funaguma, S.; Kanda, T.; Tamura, T.; Shimada, T. Analysis of the Biological Functions of a Doublesex Homologue in Bombyx mori. Dev. Genes Evol. 2003, 213, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhan, S.; Chen, S.; Zeng, B.; Li, Z.; James, A.A.; Tan, A.; Huang, Y. Sexually Dimorphic Traits in the Silkworm, Bombyx mori, Are Regulated by Doublesex. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2017, 80, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, Y.; Kobayashi, K.; Watanabe, H.; Iguchi, T. Environmental Sex Determination in the Branchiopod Crustacean Daphnia magna: Deep Conservation of a Doublesex Gene in the Sex-Determining Pathway. PLoS Genet. 2011, 7, e1001345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, P.; Zhou, T.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yi, J.; Lin, W.; Guo, Z.; Xu, A.; Yang, S.; Chan, S.; et al. Potential Involvement of a DMRT Family Member (Mr-Dsx) in the Regulation of Sexual Differentiation and Moulting in the Giant River Prawn Macrobrachium rosenbergii. Aquac. Res. 2019, 50, 3037–3049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phoungpetchara, I.; Tinikul, Y.; Poljaroen, J.; Chotwiwatthanakun, C.; Vanichviriyakit, R.; Sroyraya, M.; Hanna, P.J.; Sobhon, P. Cells Producing Insulin-like Androgenic Gland Hormone of the Giant Freshwater Prawn, Macrobrachium rosenbergii, Proliferate Following Bilateral Eyestalk-Ablation. Tissue Cell 2011, 43, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bugnot, A.B.; López Greco, L.S. Sperm Production in the Red Claw Crayfish Cherax quadricarinatus (Decapoda, Parastacidae). Aquaculture 2009, 295, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumura, T.; Hara, M. Androgenic Gland Cell Structure and Spermatogenesis during the Molt Cycle and Correlation to Morphotypic Differentiation in the Giant Freshwater Prawn, Macrobrachium rosenbergii. Zool. Sci. 2004, 21, 621–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Experiments (Month) | Initial BW (g) a | Water Temperature (°C) b | Tank Condition | Light Condition c | Treatment d | Sampling Days |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exp. 1 (November) | 22.6 ± 2.8 | 20.8 (19.1–22.4) | 2-ton FRP tank in outdoor vinyl greenhouse | Covered with opaque light-shielding sheets (≥99% shading) | Bilateral ESA | 0, 4, 7, 14 |

| Exp. 2 (January~ February) | 31.4 ± 1.9 | 14.1 (13.0–15.4) | Outdoor 6-ton reinforced concrete tank | Covered with light-shielding sheets (95~98% shading) | Bilateral ESA | 0, 14, 22 |

| Exp. 3 (November~ December) | 8.78 ± 1.4 | 18.1 (16.0–19.1) | 2-ton FRP tank in outdoor vinyl greenhouse | Covered with opaque light-shielding sheets (≥99% shading) | Bilateral and unilateral ESA | 0, 7, 14 |

| Name | Sequence (5′-3′) |

|---|---|

| Maj-IAG_fwd a | CCTTGACCTGTTCCCTCAACA |

| Maj-IAG_rev a | CCTTTCCTTTGTCCCTTCCAGAT |

| Maj-IAG_probe a | CGCTTCCACCCTCGAGCCCTG |

| Maj-Dsx1_fwd b | CATCAGCGATTACCCCCTTA |

| Maj-Dsx1_rev b | CCCAGGGTTGTGTGAAGCTA |

| Maj-Dsx2_fwd b | GGAGGCACCAGGATATGAAA |

| Maj-Dsx2_rev b | GAGAGAAGCCTCCTGCGTAA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Furukawa, T.; Yamane, F.; Okumura, T.; Miyazaki, T.; Tsutsui, N. The Effects of Eyestalk Ablation on the Androgenic Gland and the Male Reproductive Organs in the Kuruma Prawn Marsupenaeus japonicus. Animals 2025, 15, 3556. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243556

Furukawa T, Yamane F, Okumura T, Miyazaki T, Tsutsui N. The Effects of Eyestalk Ablation on the Androgenic Gland and the Male Reproductive Organs in the Kuruma Prawn Marsupenaeus japonicus. Animals. 2025; 15(24):3556. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243556

Chicago/Turabian StyleFurukawa, Takehiro, Fumihiro Yamane, Takuji Okumura, Taeko Miyazaki, and Naoaki Tsutsui. 2025. "The Effects of Eyestalk Ablation on the Androgenic Gland and the Male Reproductive Organs in the Kuruma Prawn Marsupenaeus japonicus" Animals 15, no. 24: 3556. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243556

APA StyleFurukawa, T., Yamane, F., Okumura, T., Miyazaki, T., & Tsutsui, N. (2025). The Effects of Eyestalk Ablation on the Androgenic Gland and the Male Reproductive Organs in the Kuruma Prawn Marsupenaeus japonicus. Animals, 15(24), 3556. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243556