Inactivated Type ‘O’ Foot and Mouth Disease Virus Encapsulated in Chitosan Nanoparticles Induced Protective Immune Response in Guinea Pigs

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Virus and Cell Types

2.2. Laboratory Animals

2.3. Preparation and Purification of FMDV 146S Antigen

2.4. Inactivation of FMDV by Binary Ethyleneimine

2.5. Preparation of Chitosan Nanoparticles (CS-NPs)

2.6. Preparation of Chitosan Nanoparticles with Inactivated FMDV 146S Antigen

2.7. Characterization of Chitosan Nanoparticles

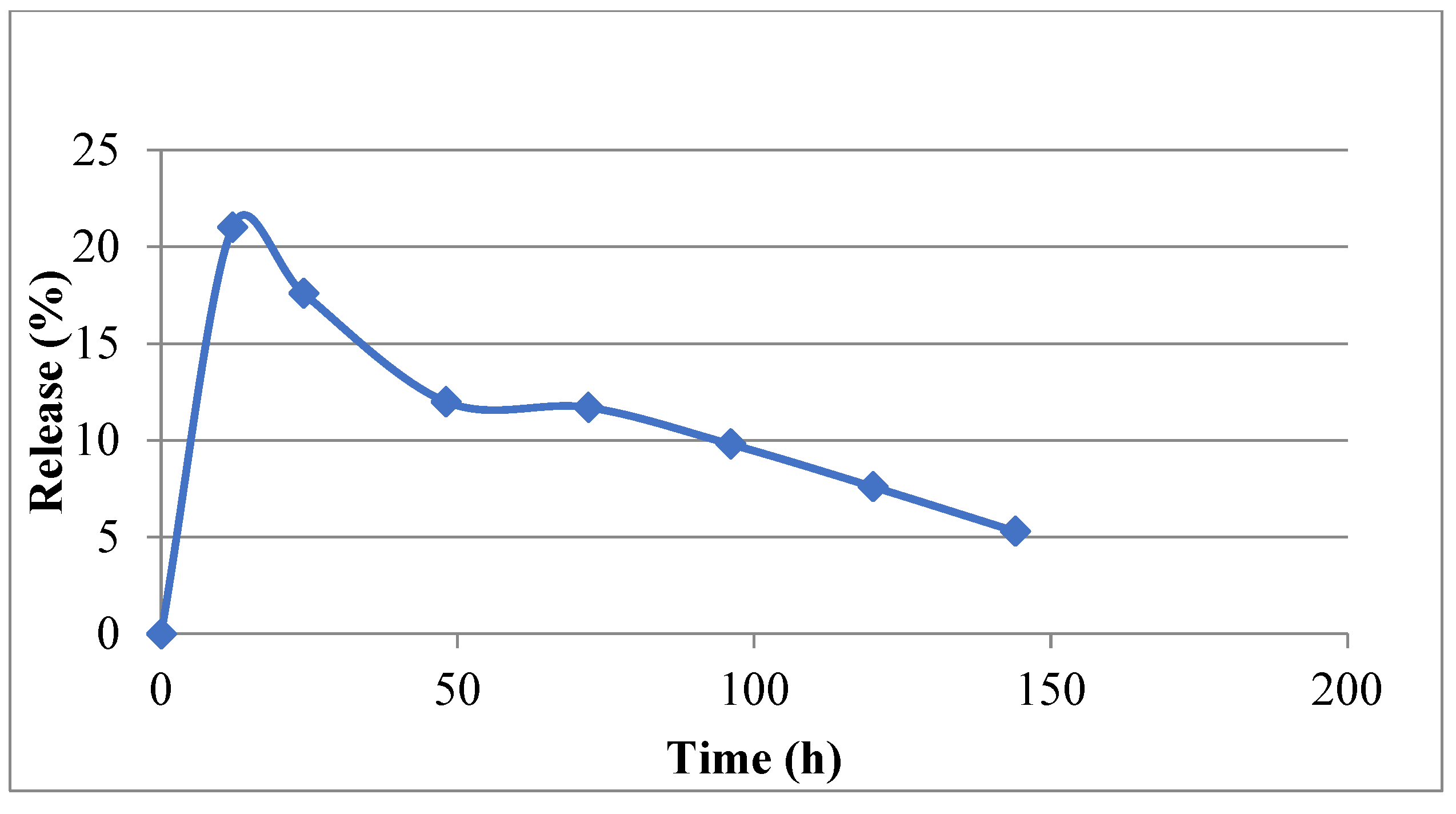

2.8. Estimation of Antigen Loading Efficiency and In Vitro Antigen Release

2.9. In Vivo Immunization Study

2.10. Collection of Serum and Nasal Washing

2.11. Serum Neutralization Test

2.12. Quantification of Secretory IgA (sIgA) in Nasal Washing

2.13. Quantification of Serum Antibodies by Indirect ELISA

2.14. Lymphocyte Transformation Assay (LTA)

2.15. Challenge Study

2.16. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Propagation of FMD Virus and Preparation of 146S FMDV Antigen

3.2. Confirmation of FMD Virus Inactivation and Quantification of Antigen

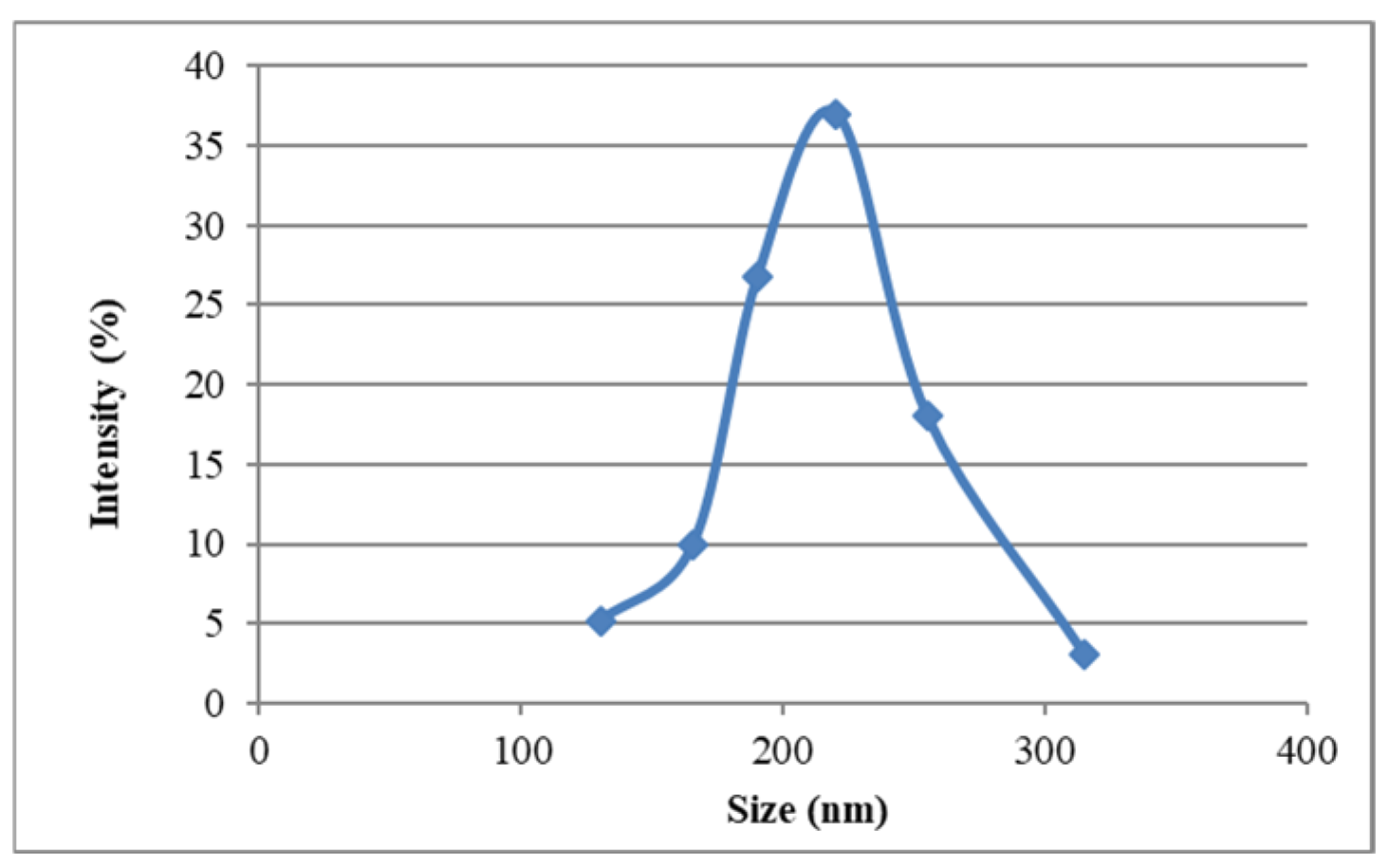

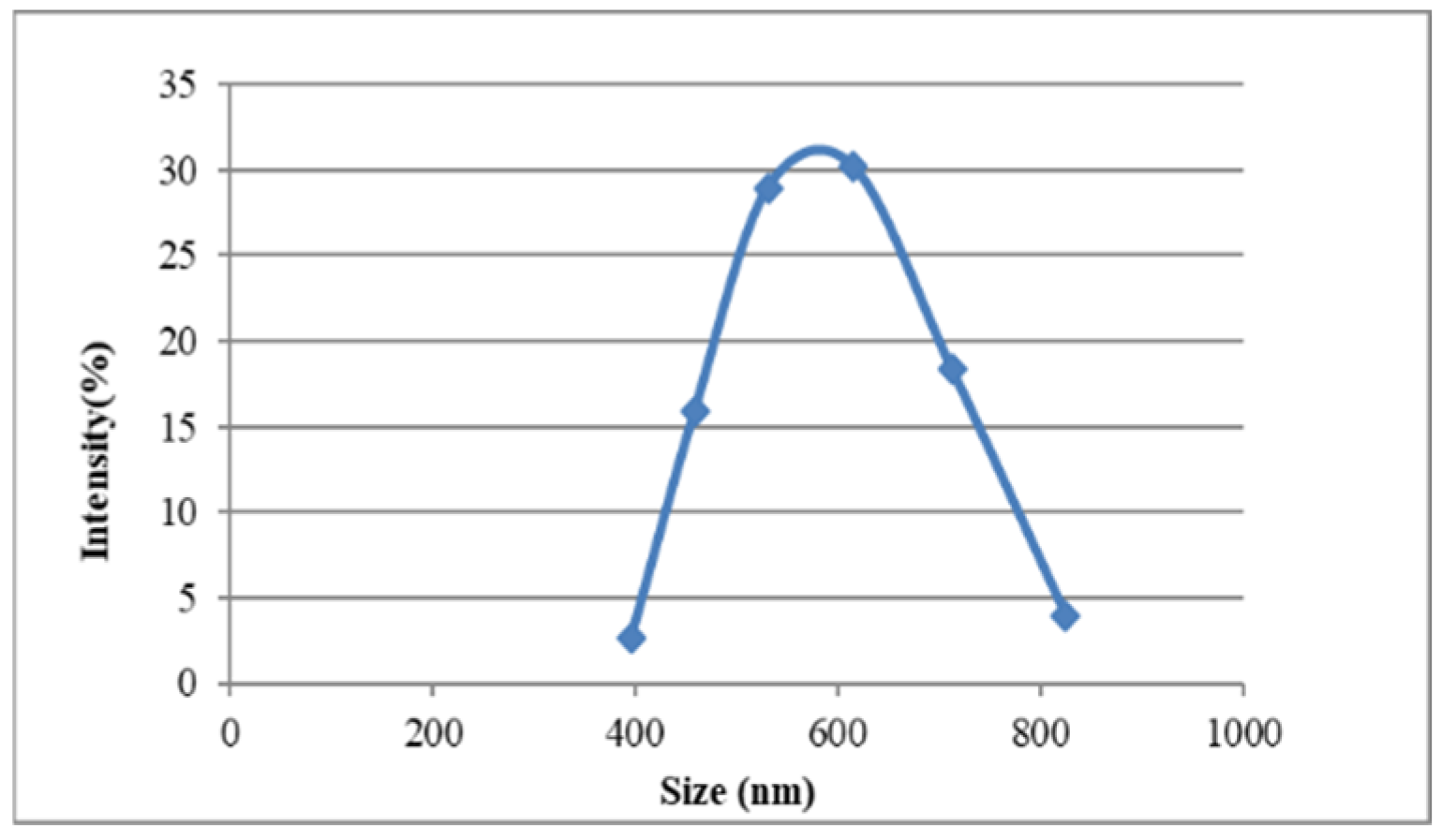

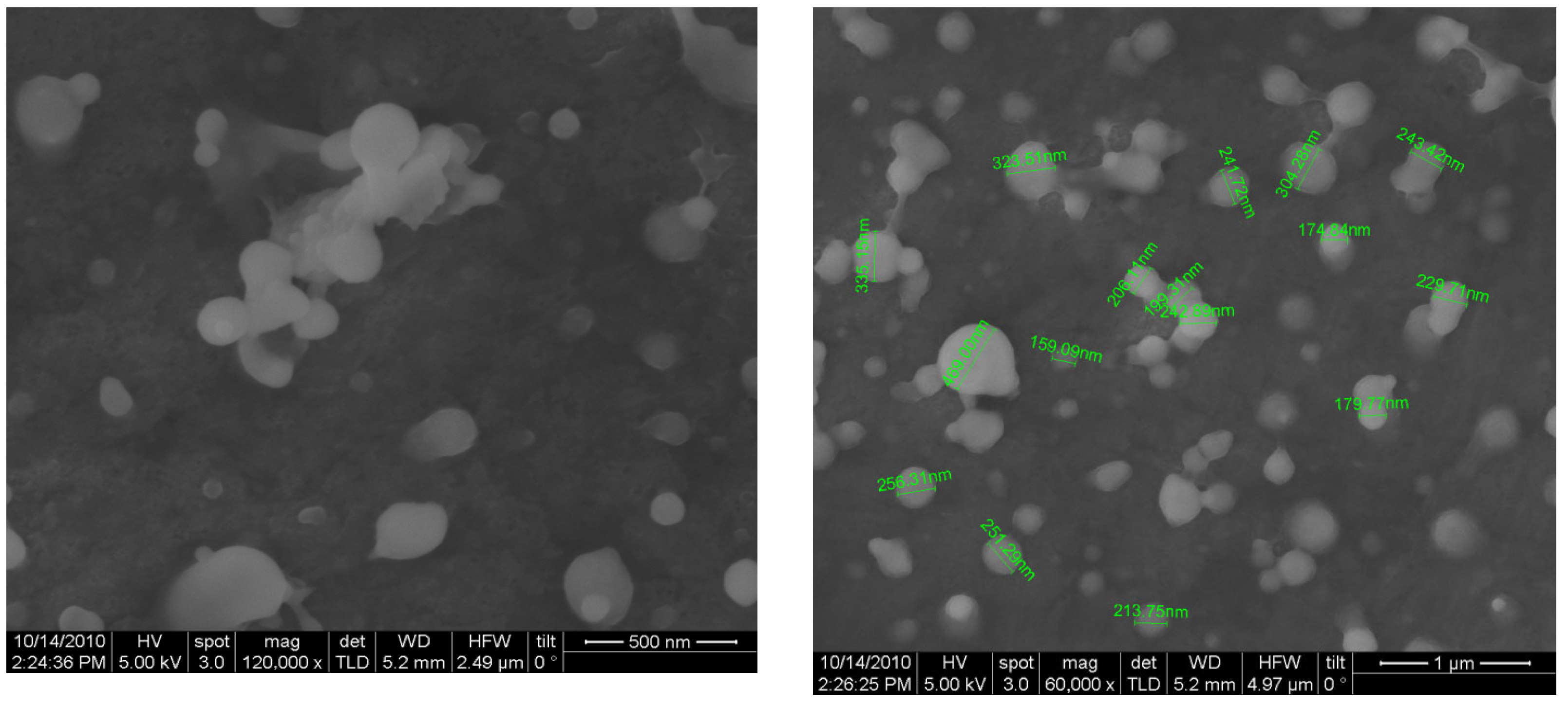

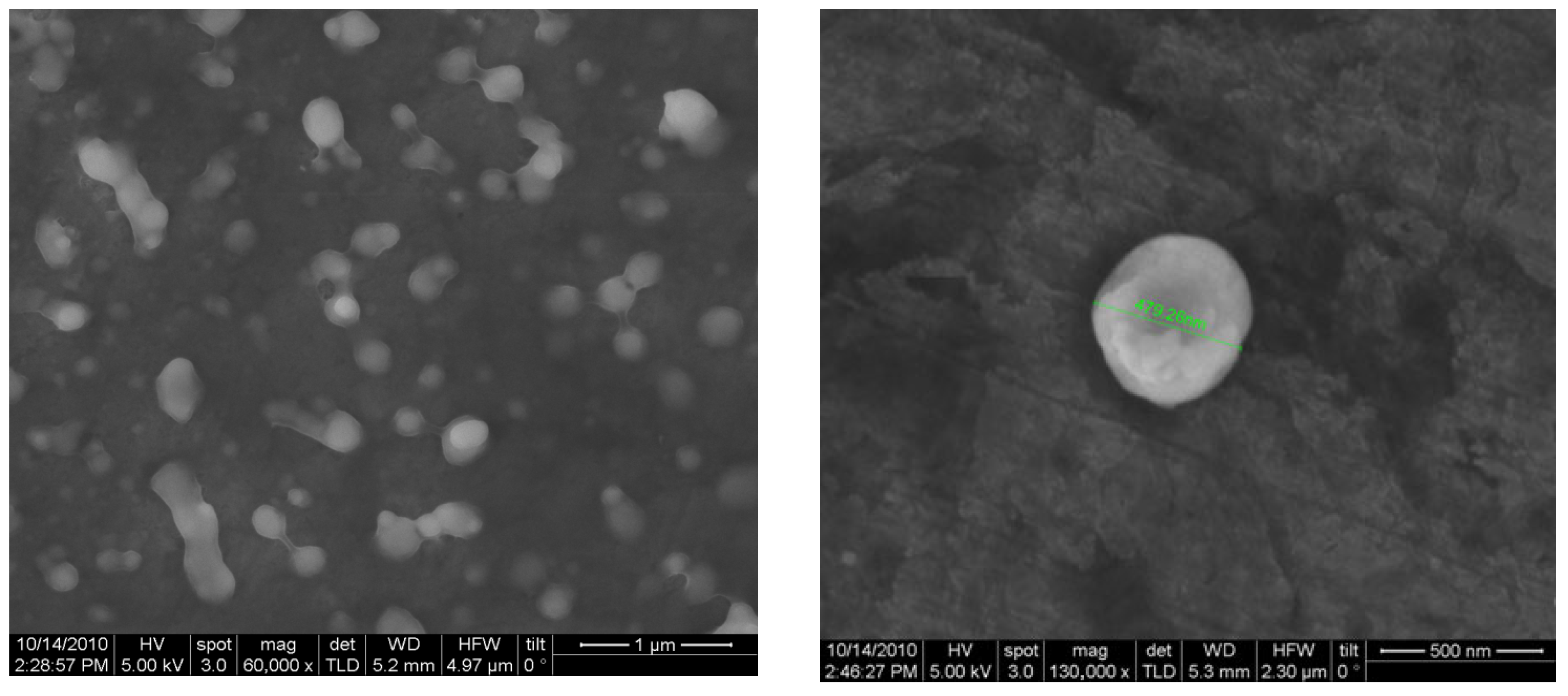

3.3. Characterization of Nanoparticle Morphology

3.4. Immunization and Evaluation of Immune Responses Against Vaccine Preparations

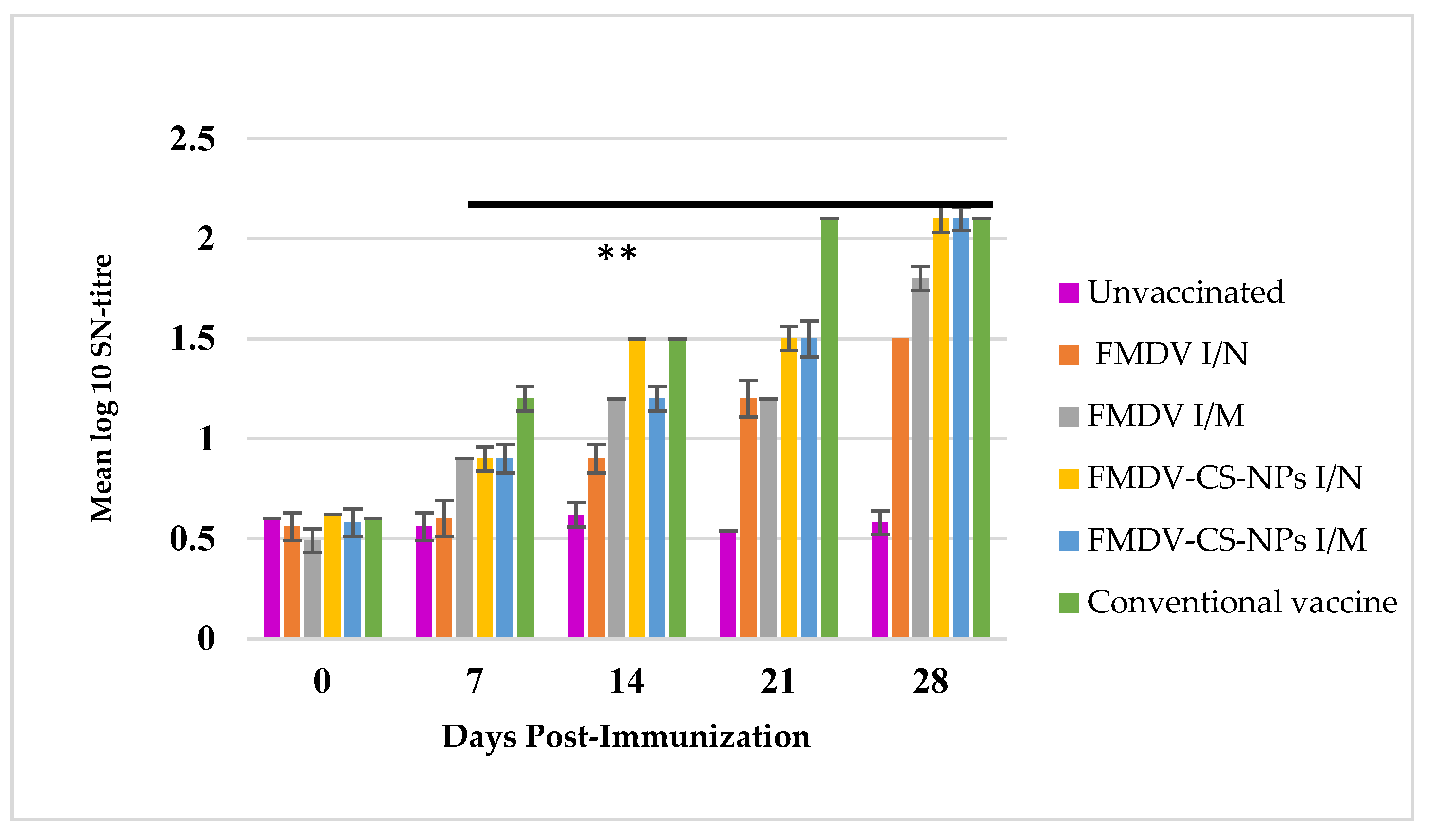

3.4.1. Serum Neutralization Assay to Estimate the Neutralizing Antibodies

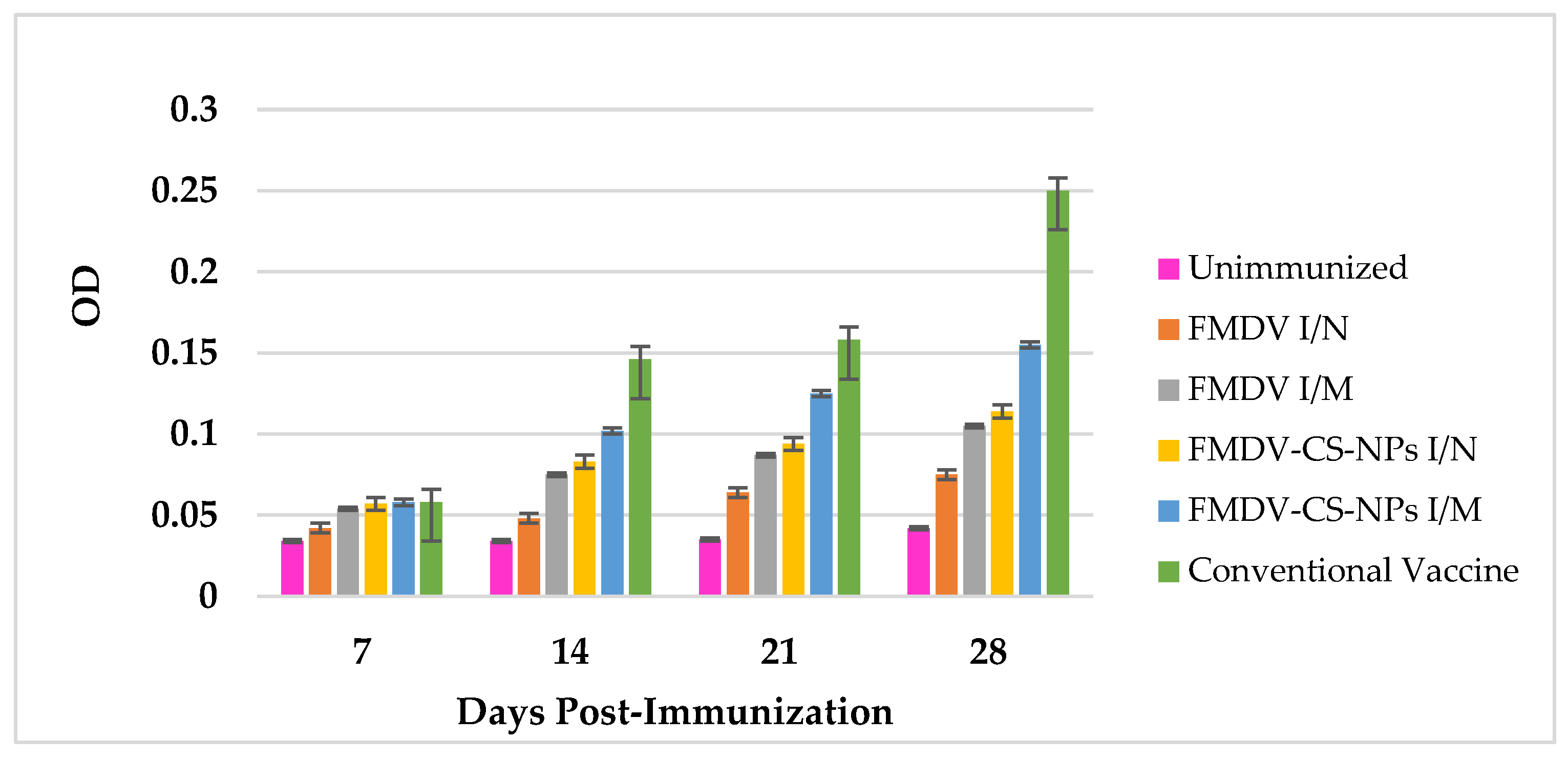

3.4.2. Nasal Secretory IgA Response Against Vaccine Preparations

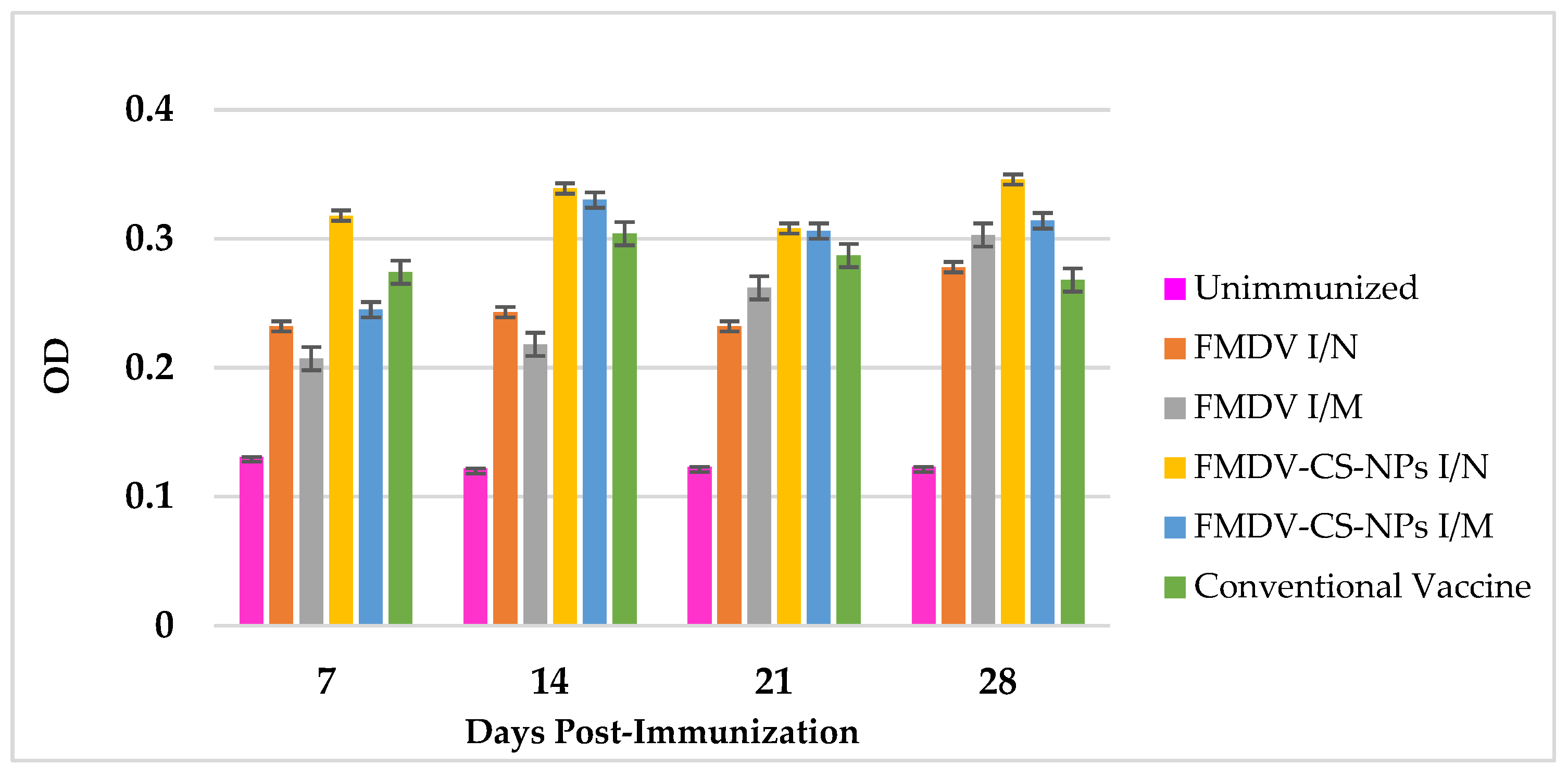

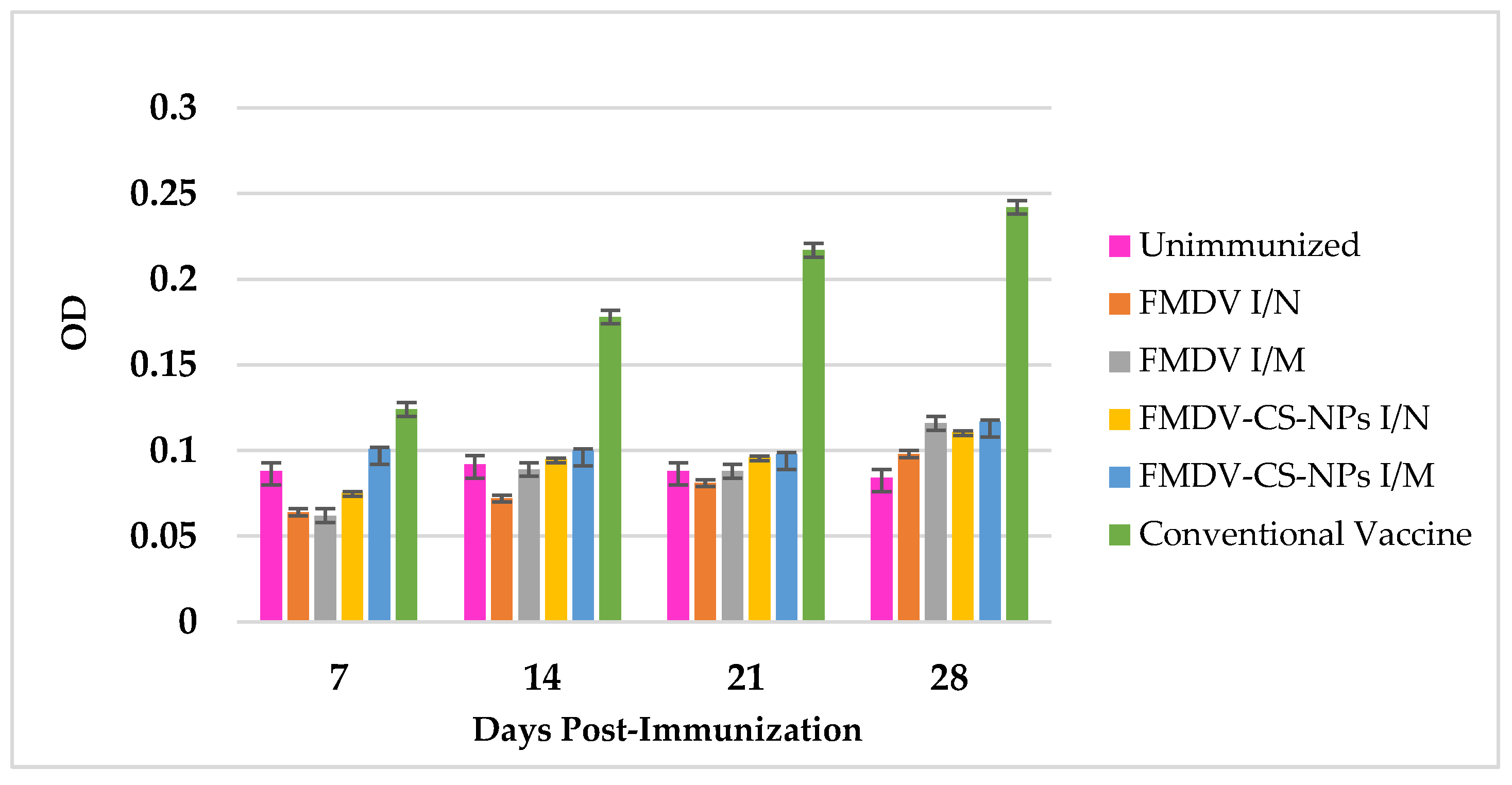

3.4.3. Total IgG Response Against Vaccine Preparations

3.4.4. IgG1 Response Against Vaccine Preparations

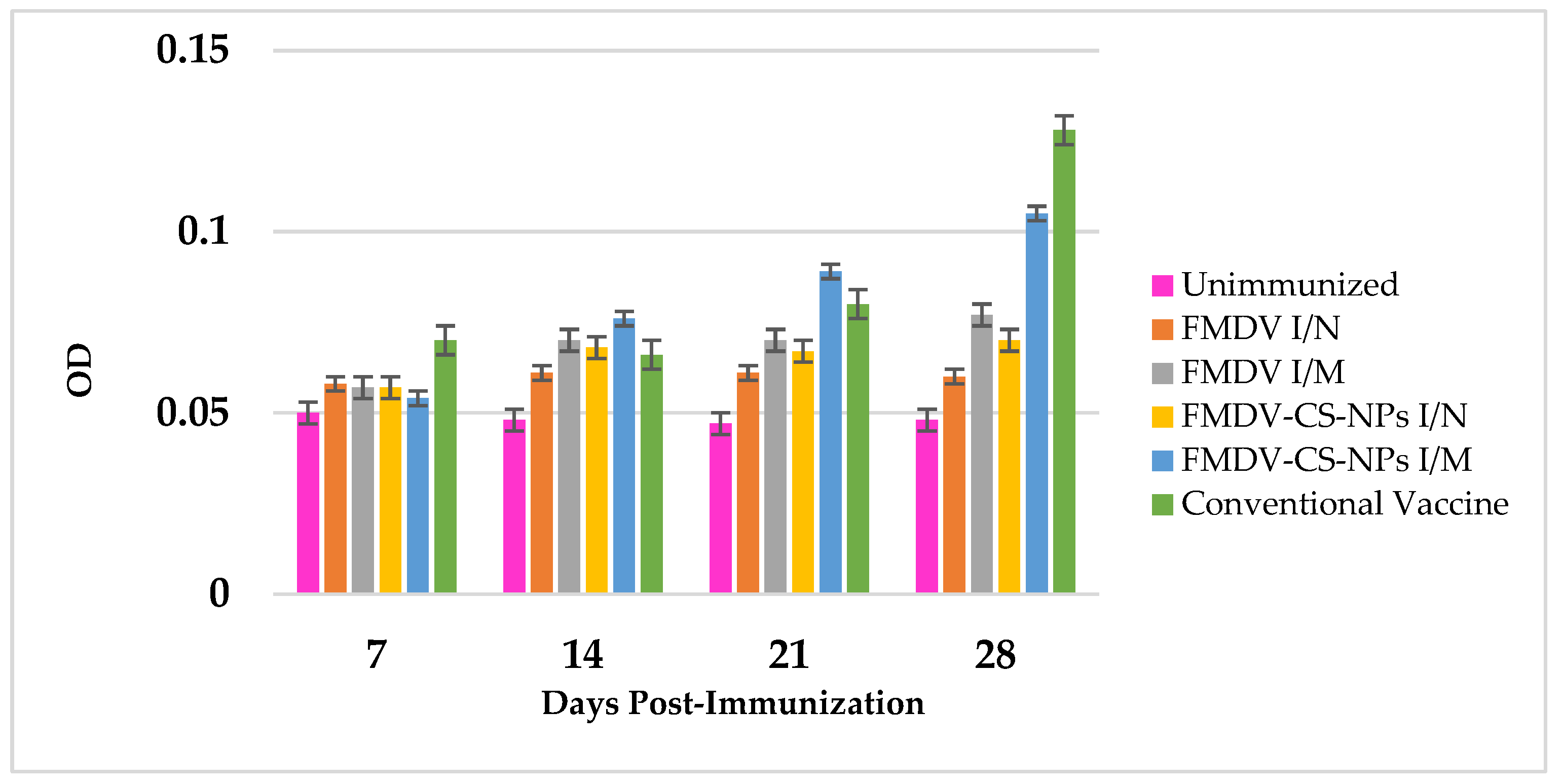

3.4.5. IgG2 Response Against Vaccine Preparations

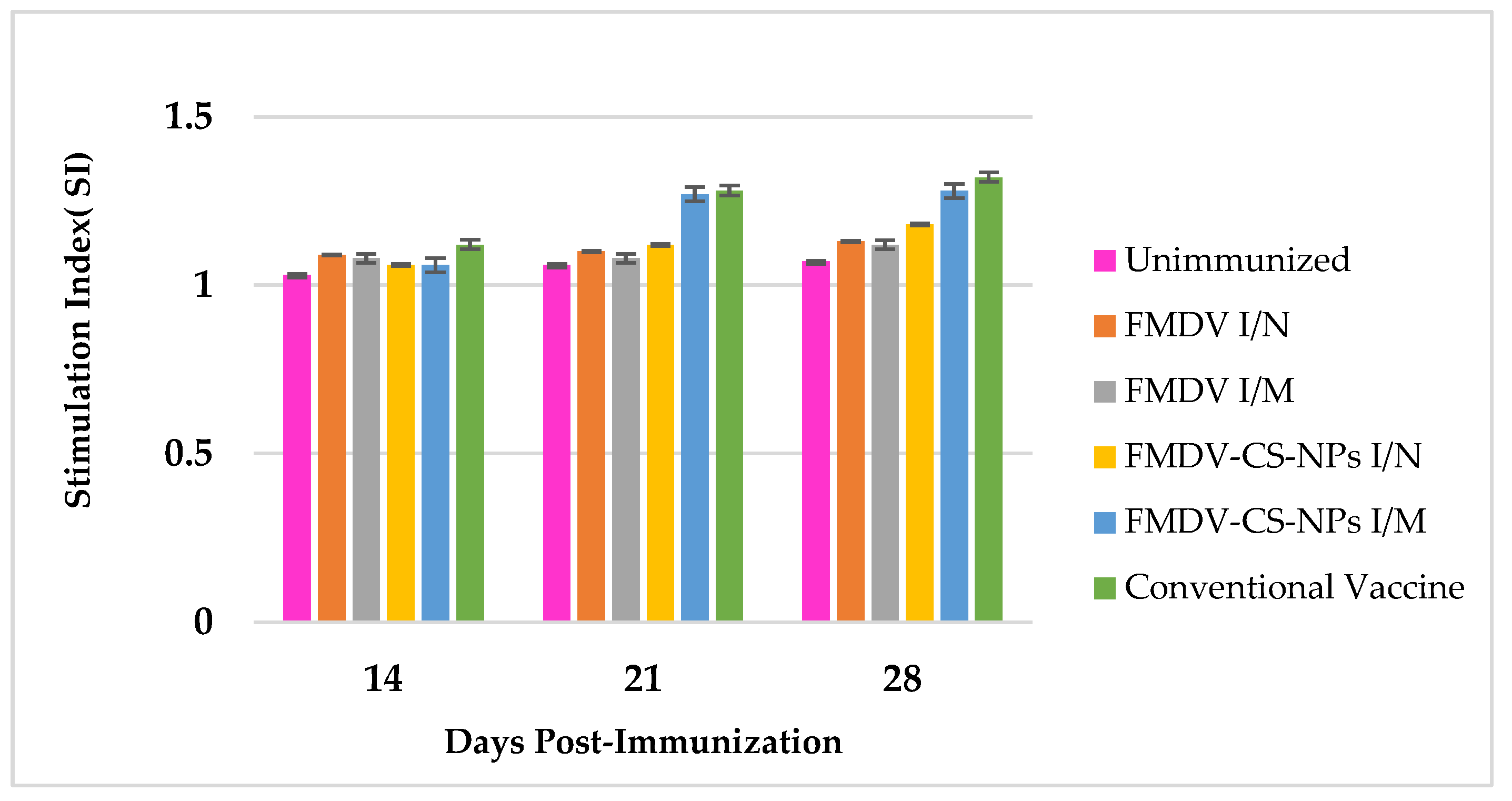

3.5. Lymphocyte Transformation Assay to Estimate CMI Response

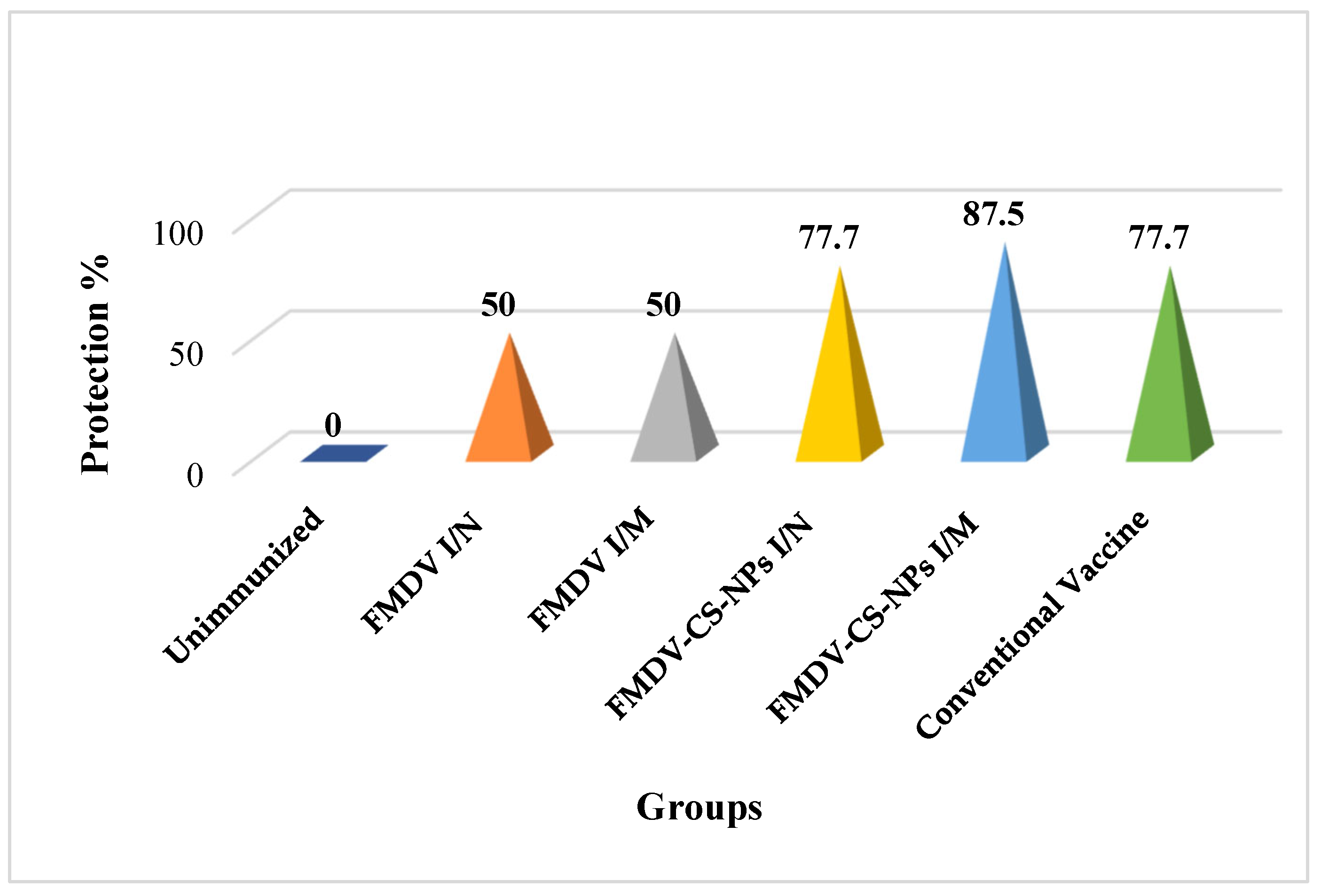

3.6. Challenge Infection to Assess the Protection Efficacy of the Vaccine Preparations

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Knight-Jones, T.J.D.; Rushton, J. The economic impacts of foot and mouth disease—What are they, how big are they and where do they occur? Prev. Vet. Med. 2013, 112, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramaniam, S.; Mohapatra, J.K.; Sahoo, N.R.; Sahoo, A.P.; Dahiya, S.S.; Rout, M.; Biswal, J.K.; Ashok, K.S.; Mallick, S.; Ranjan, R.; et al. Foot-and-mouth disease status in India during the second decade of the twenty-first century (2011–2020). Vet. Res. Commun. 2022, 46, 1011–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindaraj, G.; Krishnamohan, A.; Hegde, R.; Kumar, N.; Prabhakaran, K.; Wadhwan, V.M.; Kakker, N.; Lokhande, T.; Sharma, K.; Kanani, A. Foot and Mouth Disease (FMD) incidence in cattle and buffaloes and its associated farm-level economic costs in endemic India. Prev. Vet. Med. 2021, 190, 105318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Organization for Animal Health. Manual of Diagnostic Tests and Vaccines for Terrestrial Animals. Chapter 3.1.8. Foot and Mouth Disease (Infection with Foot and Mouth Disease Virus). 2022. Available online: https://www.woah.org/en/what-we-do/standards/codes-and-manuals/terrestrial-manual-online-access/ (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Doel, T.R. Natural and vaccine-induced immunity to foot and mouth disease: The prospects for improved vaccines. Rev. sci. tech. Off. Int. Epiz 1996, 15, 883–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doel, T.R. Natural and vaccine induced immunity to FMD. In Foot-and-Mouth Disease Virus; Mahy, B.W., Ed.; Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; Volume 288, pp. 103–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doel, T.R.; Williams, L.; Barnett, P.V. Emergency vaccination against foot-and-mouth disease: Rate of development of immunity and its implications for the carrier state. Vaccine 1994, 12, 592–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salt, J.S. The carrier state in foot and mouth disease—An immunological review. Br. Vet. J. 1993, 149, 207–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyslop, N.S.G.; Davie, J.; Carter, S.P. Antigenic differences between strains of foot-and-mouth disease virus of type SAT 1. J. Hyg. 1963, 61, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pega, J.; Di Giacomo, S.; Bucafusco, D.; Schammas, J.M.; Malacari, D.; Barrionuevo, F.; Capozzo, A.V.; Rodríguez, L.L.; Borca, M.V.; Pérez-Filgueira, M. Systemic foot-and-mouth disease vaccination in cattle promotes specific antibody-secreting cells at the respiratory tract and triggers local anamnestic responses upon aerosol infection. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 9581–9590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doel, T.R.; Chong, W.K.T. Comparative immunogenicity of 146S, 75S and 12S particles of foot-and mouth disease virus. Arch. Virol. 1982, 73, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Office of Epizootics; Biological Standards Commission; International Office of Epizootics; International Committee. Manual of Diagnostic Tests and Vaccines for Terrestrial Animals: Mammals, Birds and Bees; Office International des Epizooties: Paris, France, 2008; Volume 2, Available online: https://books.google.co.in/books?id=xmZWAAAAYAAJ (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Stenfeldt, C.; Pacheco, J.; Smoliga, G.; Bishop, E.; Pauszek, S.; Hartwig, E.; Rodriguez, L.; Arzt, J. Detection of foot-and-mouth disease virus RNA and capsid protein in lymphoid tissues of convalescent pigs does not indicate existence of a carrier state. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2016, 63, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabi, M.; Montazeri, H.; Mohamadpour Dounighi, N.; Rashti, A.; Vakili-Ghartavol, R. Chitosan-based Nanoparticles in Mucosal Vaccine Delivery. Arch. Razi Inst. 2018, 73, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnihotri, S.A.; Mallikarjuna, N.N.; Aminabhavi, T.M. Recent advances on chitosan-based micro- and nanoparticles in drug delivery. J. Control. Release 2004, 100, 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadpourdounighi, N.; Behfar, A.; Ezabadi, A.; Zolfagharian, H.; Heydari, M. Preparation of chitosan nanoparticles containing Naja naja oxiana snake venom. Nanomedicine 2010, 6, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijesena, R.N.; Tissera, N.; Kannangara, Y.Y.; Lin, Y.; Amaratunga, G.A.; de Silva, K.N. A method for top down preparation of chitosan nanoparticles and nanofibers. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 117, 731–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Lubben, I.M.; Verhoef, J.C.; Borchard, G.; Junginger, H.E. Chitosan for mucosal vaccination. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2001, 52, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renu, S.; Markazi, A.D.; Dhakal, S.; Lakshmanappa, Y.S.; Shanmugasundaram, R.; Selvaraj, R.K.; Renukaradhya, G.J. Oral Deliverable Mucoadhesive Chitosan-Salmonella Subunit Nanovaccine for Layer Chickens. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020, 15, 761–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.; Gupta, M.; Gupta, V.; Gogoi, H.; Bhatnagar, R. Novel application of trimethyl chitosan as an adjuvant in vaccine delivery. Int. J. Nanomed. 2018, 13, 7959–7970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, H.; Wu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Niu, H.; Li, C. Nasal absorption enhancement of insulin using PEG-grafted chitosan nanoparticles. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2008, 68, 526–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atmar, R.L.; Bernstein, D.I.; Harro, C.D.; Al-Ibrahim, M.S.; Chen, W.H.; Ferreira, J.; Estes, M.K.; Graham, D.Y.; Opekun, A.R.; Richardson, C.; et al. Norovirus vaccine against experimental human Norwalk Virus illness. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 365, 2178–2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kamary, S.S.; Pasetti, M.F.; Mendelman, P.M.; Frey, S.E.; Bernstein, D.I.; Treanor, J.J.; Ferreira, J.; Chen, W.H.; Sublett, R.; Richardson, C.; et al. Adjuvanted intranasal Norwalk virus-like particle vaccine elicits antibodies and antibody-secreting cells that express homing receptors for mucosal and peripheral lymphoid tissues. J. Infect. Dis. 2010, 202, 1649–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, S.H.; Wu, J.J.; Zhao, L.; Li, W.H.; Zhao, Y.F.; Li, Y.M. A chitosan-mediated inhalable nanovaccine against SARS-CoV-2. Nano Res. 2022, 15, 4191–4200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amidi, M.; Romeijn, S.G.; Verhoef, J.C.; Junginger, H.E.; Bungener, L.; Huckriede, A.; Crommelin, D.J.; Jiskoot, W. N-trimethyl chitosan (TMC) nanoparticles loaded with influenza subunit antigen for intranasal vaccination: Biological properties and immunogenicity in a mouse model. Vaccine 2007, 25, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.A.; Firdous, J.; Choi, Y.J.; Yun, C.H.; Cho, C.S. Design and application of chitosan microspheres as oral and nasal vaccine carriers: An updated review. Int. J. Nanomed. 2012, 7, 6077–6093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachrach, H.L.; Trautman, R.; Breese, S.S., Jr. Chemical Physical Properties of Virtually Pure Foot-and-Mouth Disease Virus. Am. J. Vet. Res. 1964, 25, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- World Organisation for Animal Health. OIE Terrestrial Manual; Foot and mouth disease; World Organisation for Animal Health: Paris, France, 2009; Chapter 2.1.5. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo, P.; Remunan-Lopez, C.; Vila-Jato, J.L.; Alonso, M.J. Novel hydrophilic chitosan-polyethylene oxide nanoparticles as protein carrier. J. Appl. Poly. Sci. 1997, 63, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudner, B.C.; Verhoef, J.C.; Giuliani, M.M.; Peppoloni, S.; Rappuoli, R.; Del Giudice, G.; Junginger, H.E. Protective immune responses to meningococcal C conjugate vaccine after intranasal immunization of mice with the LTK63 mutant plus chitosan or trimethyl chitosan chloride as novel delivery platform. J. Drug Target. 2005, 13, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.L.; Kang, S.G.; Jiang, H.L.; Shin, S.W.; Lee, D.Y.; Ahn, J.M. In vivo induction of mucosal immune responses by intranasal administration of chitosan microspheres containing Bordetella bronchiseptica DNT. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2006, 63, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Du, Y. Effect of molecular structure of chitosan on protein delivery properties of chitosan nanoparticles. Int. J. Pharm. 2003, 250, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, S.K.; Andracki, M.E.; Krieg, A.M. Biodegradable microspheres containing group B Streptococcus vaccine: Immune response in mice. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2001, 185, 1174–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogarth, P.J.; Jahans, K.J.; Hecker, R.; Hewinson, R.G.; Chambers, M.A. Evaluation of adjuvants for protein vaccines against tuberculosis in guinea pigs. Vaccine 2003, 21, 977–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyum, A. Separation of leucocytes from blood and bone marrow. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Investig. 1968, 21 (Suppl. S97), 7. Available online: https://sid.ir/paper/550847/en (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Mosmann, T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: Application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J. Immunol. Method. 1983, 65, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Pan, L.; Zhou, P.; Lv, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Protection against Foot-and-Mouth Disease Virus in Guinea Pigs via Oral Administration of Recombinant Lactobacillus plantarum Expressing VP1. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0143750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubman, M.J.; Baxt, B. Foot-and-mouth disease. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2004, 17, 465–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenfeldt, C.; Eschbaumer, M.; Rekant, S.I.; Pacheco, J.M.; Smoliga, G.R.; Hartwig, E.J.; Rodriguez, L.L.; Arzt, J. The foot-and-mouth disease carrier state divergence in cattle. J. Virol. 2016, 90, 6344–6364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omidian, H.; Gill, E.J.; Dey Chowdhury, S.; Cubeddu, L.X. Chitosan Nanoparticles for Intranasal Drug Delivery. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Wang, Y.; Shang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, X. How foot-and-mouth disease virus receptor mediates foot-and-mouth disease virus infection. Virol. J. 2015, 12, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, M.R.; Rootes, C.L.; van Vuren, P.J.; Stewart, C.R. Concentration of infectious SARS-CoV-2 by polyethylene glycol precipitation. J. Virol. Methods 2020, 286, 113977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucafusco, D.; Di Giacomo, S.; Pega, J.; Schammas, J.M.; Cardoso, N.; Capozzo, A.V.; Perez-Filgueira, M. Foot-and-mouth disease vaccination induces cross-reactive IFN-γ responses in cattle that are dependent on the integrity of the 140S particles. Virology 2015, 476, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, G.S.; Shanmuganathan, S.; Manikandan, R.; Hosamani, M.; Bhanuprakash, V.; Tamilselvan, R.P.; Basagoudanavar, S.H.; Sanyal, A.; Sreenivasa, B.P. Evaluation of Different Methods for Conversion of Whole Virion Particle (146S) of FMDV into 12S Subunits and Application in Characterization of Monoclonal Antibodies. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. App. Sci. 2019, 8, 1392–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarthi, D.; Rao, K.A.; Robinson, R.; Srinivasan, V.A. Validation of binary ethyleneimine (BEI) used as an inactivant for foot and mouth disease tissue culture vaccine. Biologicals 2004, 32, 153–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ta, Q.; Ting, J.; Harwood, S.; Browning, N.; Simm, A.; Ross, K.; Olier, I.; Al-Kassas, R. Chitosan nanoparticles for enhancing drugs and cosmetic components penetration through the skin. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 160, 105765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Chen, G.; Shi, X.-M.; Gao, T.-T.; Li, W.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, F.-Q.; Wu, J.; Cui, X.; Wang, Y.-F. Preparation and efficacy of a live newcastle disease virus vaccine encapsulated in chitosan nanoparticles. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e53314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadpour Dounighi, N.; Eskandari, R.; Avadi, M.R.; Zolfagharian, H.; Mir Mohammad Sadeghi, A.; Rezayat, M.J. Preparation and in vitro characterization of chitosan nanoparticles containing Mesobuthus eupeus scorpion venom as an antigen delivery system. J. Venom. Anim. Toxins Incl. Trop. Dis. 2012, 18, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danaei, M.R.; Dehghankhold, M.; Ataei, S.; Hasanzadeh Davarani, F.; Javanmard, R.; Dokhani, A.; Khorasani, S.; Mozafari, Y.M. Impact of particle size and polydispersity index on the clinical applications of lipidic nanocarrier systems. Pharmaceutics 2018, 10, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amidi, M.; Romeijn, S.G.; Borchard, G.; Junginger, H.E.; Hennink, W.E.; Jiskoot, W. Preparation and characterization of protein-loaded N-trimethyl chitosan nanoparticles as nasal delivery system. J. Control. Release 2006, 111, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.B.; Deng, X.M.; Li, X. Investigation on a novelcore-coated microspheres protein delivery system. J. Control. Release 2001, 75, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dailey, L.A.; Wittmar, M.; Kissel, T. The role of branched polyesters and their modifications in the development of modern drug delivery vehicles. J. Control. Release 2005, 101, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Ru, Y.; Hao, R.; Yang, Y.; Liu, H.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Mao, Y.; Yang, R.; Pan, Y.; et al. A ferritin-based nanoparticle displaying a neutralizing epitope for foot-and-mouth disease virus (FMDV) confers partial protection in guinea pigs. BMC Vet. Res. 2024, 20, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn-Walters, D.K.; Isaacson, P.G.; Spencer, J. Analysis of mutations in immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region genes of microdissected marginal zone (MGZ) B cells suggests that the MGZ of human spleen is a reservoir of memory B cells. J. Exp. Med. 1995, 182, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, Y. Memory B Cells in Systemic and Mucosal Immune Response: Implications for Successful Vaccination. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2007, 71, 2358–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, H.; Yang, Y.; Tu, Z.; Tang, M.; Jing, B.; Feng, Y.; Xie, J.; Gao, H.; Song, X.; Zhao, X. Enhanced mucosal immune response through nanoparticle delivery system based on chitosan-catechol and a recombinant antigen targeted towards M cells. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 306, 141345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, L.H.; Saul, A.; Mahanty, S. Revisiting Freund’s incomplete adjuvant for vaccines in the developing world. Trends Parasitol. 2005, 21, 412–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, A.P.; McClellan, H.A.; Rausch, K.M.; Zhu, D.; Whitmore, M.D.; Singh, S.; Laura, B.M.; Wu, Y.; Giersing, B.K.; Anthony, W.S.; et al. Montanide ISA 720 vaccines: Quality control of emulsions, stability of formulated antigens, and comparative immunogenicity of vaccine formulations. Vaccines 2005, 23, 2530–2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, H.T.; Cheng, S.C.; Sin, F.W.; Chan, E.W.; Sheng, Z.T.; Xie, Y. A DNA vaccine against foot-and-mouth disease elicits an immune response in swine which is enhanced by co-administration with interleukin-2. Vaccine 2002, 20, 2641–2647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summerfield, A.; Gerber, H.; Schmitt, R.; Liniger, M.; Grazioli, S.; Brocchi, E. Relationship between neutralizing and opsonizing monoclonal antibodies against foot-and-mouth disease virus. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 1033276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group | Inoculum | Route of Immunization |

|---|---|---|

| I | Unvaccinated control | - |

| II | Inactivated type ‘O’ FMDV (2 µg/100 µL) | Intranasal (I/N) |

| III | Inactivated type ‘O’ FMDV (2 µg/100 µL) | Intramuscular (I/M) |

| IV | Chitosan loaded with inactivated type ‘O’ FMDV (2 µg/100 µL)—FMDV-CS-NPs | Intranasal (I/N) |

| V | Chitosan loaded with inactivated type ‘O’ FMDV (2 µg/100 µL)—FMDV-CS-NPs | Intramuscular (I/M) |

| VI | Inactivated mineral oil-adjuvanted type ‘O’ FMDV vaccine (2 µg) | Intramuscular (I/M) |

| Fraction | OD at 259 nm | OD at 239 nm | A259/A239 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.9546 | 1.2442 | 1.3033 |

| 2 | 1.0663 | 1.4975 | 1.404 |

| 3 | 1.0078 | 1.4276 | 1.416 |

| 4 | 0.9076 | 1.2969 | 1.428 |

| 5 | 1.6836 | 2.0839 | 1.2377 |

| 6 | 2.8817 | 3.2520 | 1.128 |

| Count (Number of Particles) | Zeta Potential (mV) |

|---|---|

| 492,148 | 46.97 |

| 472,650 | 50.09 |

| 402,467 | 53.21 |

| 267,946 | 56.34 |

| 153,962 | 40.72 |

| 348,875 | 43.85 |

| 29,759 | 31.36 |

| Count (No. of Particles) | Zeta Potential (mV) |

|---|---|

| 19,266 | 23.89 |

| 42,073 | 20.77 |

| 230,090 | 11.4 |

| 200,554 | 17.64 |

| 319,763 | 14.52 |

| Sample | Total Amount of Antigen Loaded (µg) | Unbound Antigen in Supernatant (µg) | Loading Efficiency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 280 | 100 | 64.2 |

| 2 | 500 | 157 | 68.6 |

| 3 | 350 | 113 | 67.7 |

| Average loading efficiency = 66.8 ± 2.3 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ramya, K.; Kishore, S.; Sankar, P.; Kondabatulla, G.; Edao, B.M.; Saravanan, R.; Karthik, K. Inactivated Type ‘O’ Foot and Mouth Disease Virus Encapsulated in Chitosan Nanoparticles Induced Protective Immune Response in Guinea Pigs. Animals 2025, 15, 3540. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243540

Ramya K, Kishore S, Sankar P, Kondabatulla G, Edao BM, Saravanan R, Karthik K. Inactivated Type ‘O’ Foot and Mouth Disease Virus Encapsulated in Chitosan Nanoparticles Induced Protective Immune Response in Guinea Pigs. Animals. 2025; 15(24):3540. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243540

Chicago/Turabian StyleRamya, Kalaivanan, Subodh Kishore, Palanisamy Sankar, Ganesh Kondabatulla, Bedaso Mamo Edao, Ramasamy Saravanan, and Kumaraguruban Karthik. 2025. "Inactivated Type ‘O’ Foot and Mouth Disease Virus Encapsulated in Chitosan Nanoparticles Induced Protective Immune Response in Guinea Pigs" Animals 15, no. 24: 3540. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243540

APA StyleRamya, K., Kishore, S., Sankar, P., Kondabatulla, G., Edao, B. M., Saravanan, R., & Karthik, K. (2025). Inactivated Type ‘O’ Foot and Mouth Disease Virus Encapsulated in Chitosan Nanoparticles Induced Protective Immune Response in Guinea Pigs. Animals, 15(24), 3540. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243540