Molecular Epidemiology and Antibiotic Resistance of Sheep-Derived Mannheimia haemolytica in Northwestern China

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

2.2. Pathogen Isolation and Identification

2.3. DNA Extraction and 16S rRNA Gene Amplification

2.4. Serotype Identification

2.5. Next-Generation Sequencing and Data Processing

2.6. Comparative Genomic Analysis

2.7. Drug Resistance Analysis

2.8. Pathogenicity Experiment

2.9. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Distribution of Isolated Bacterial Strains

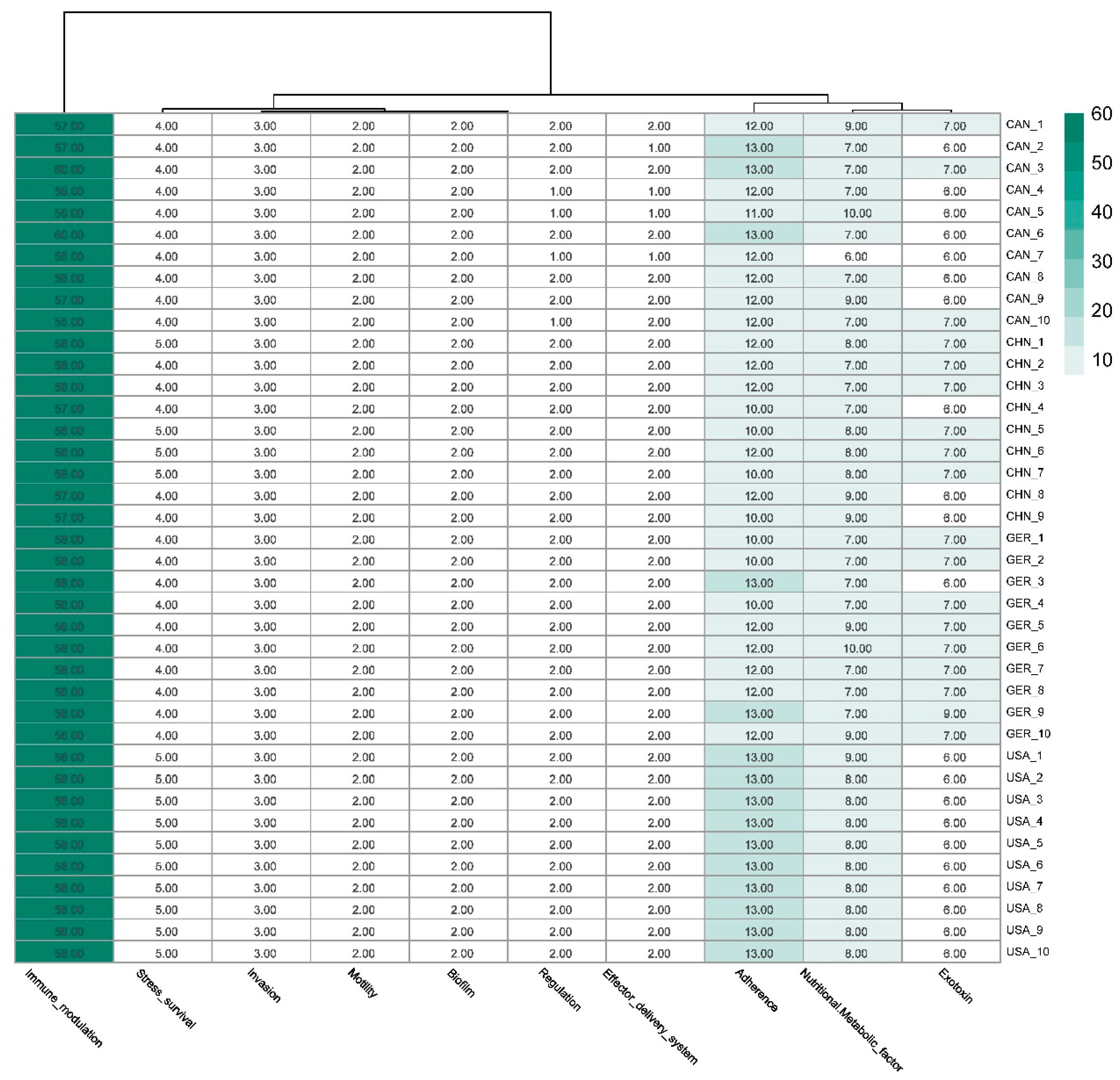

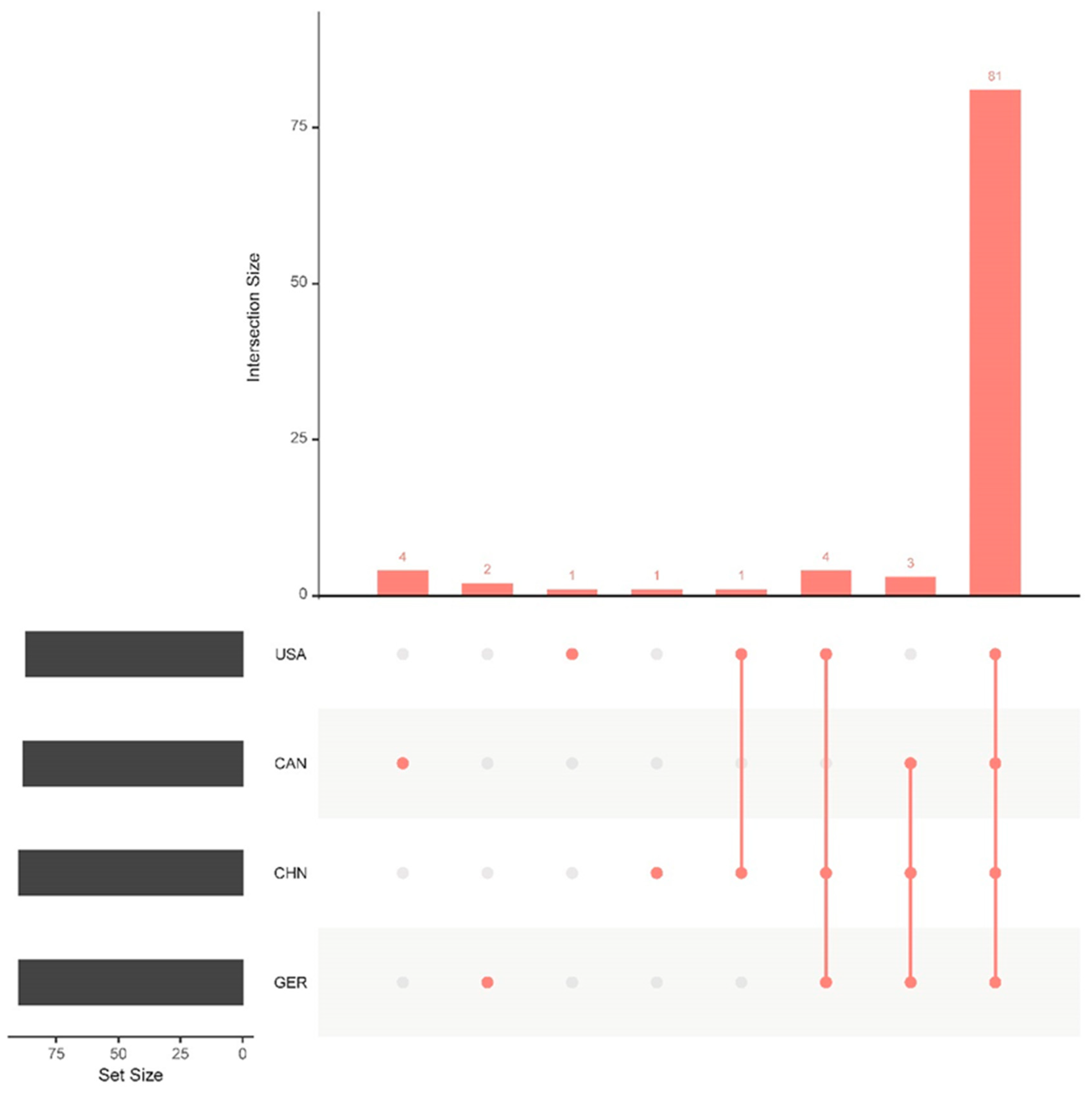

3.2. Virulence Gene Comparison Analysis

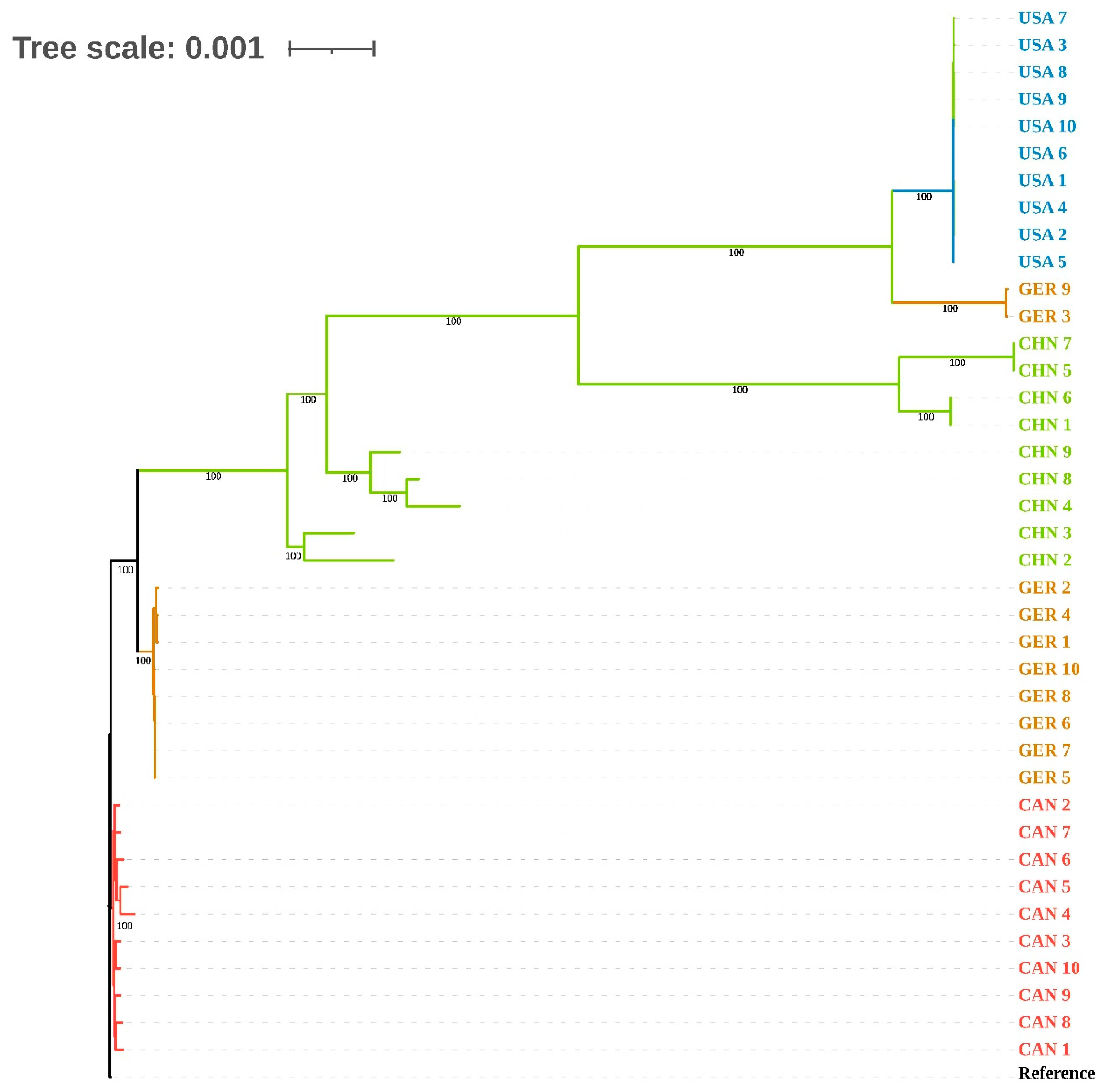

3.3. cgSNP and Phylogenetic Analysis of Genomes

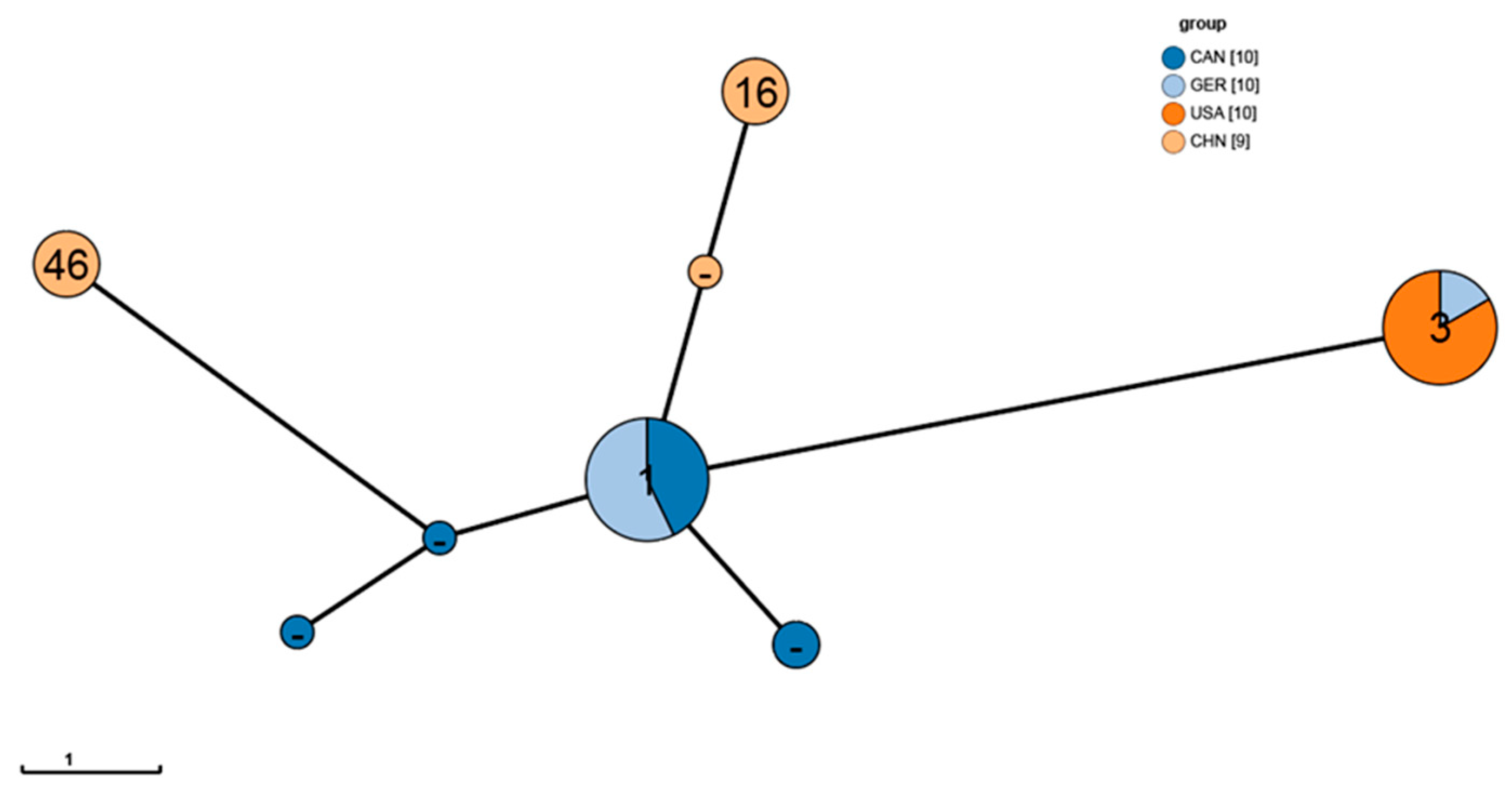

3.4. Genomic MLST Analysis

3.5. Drug Resistance Analysis

3.5.1. Distribution of Drug Resistance and Related Genes

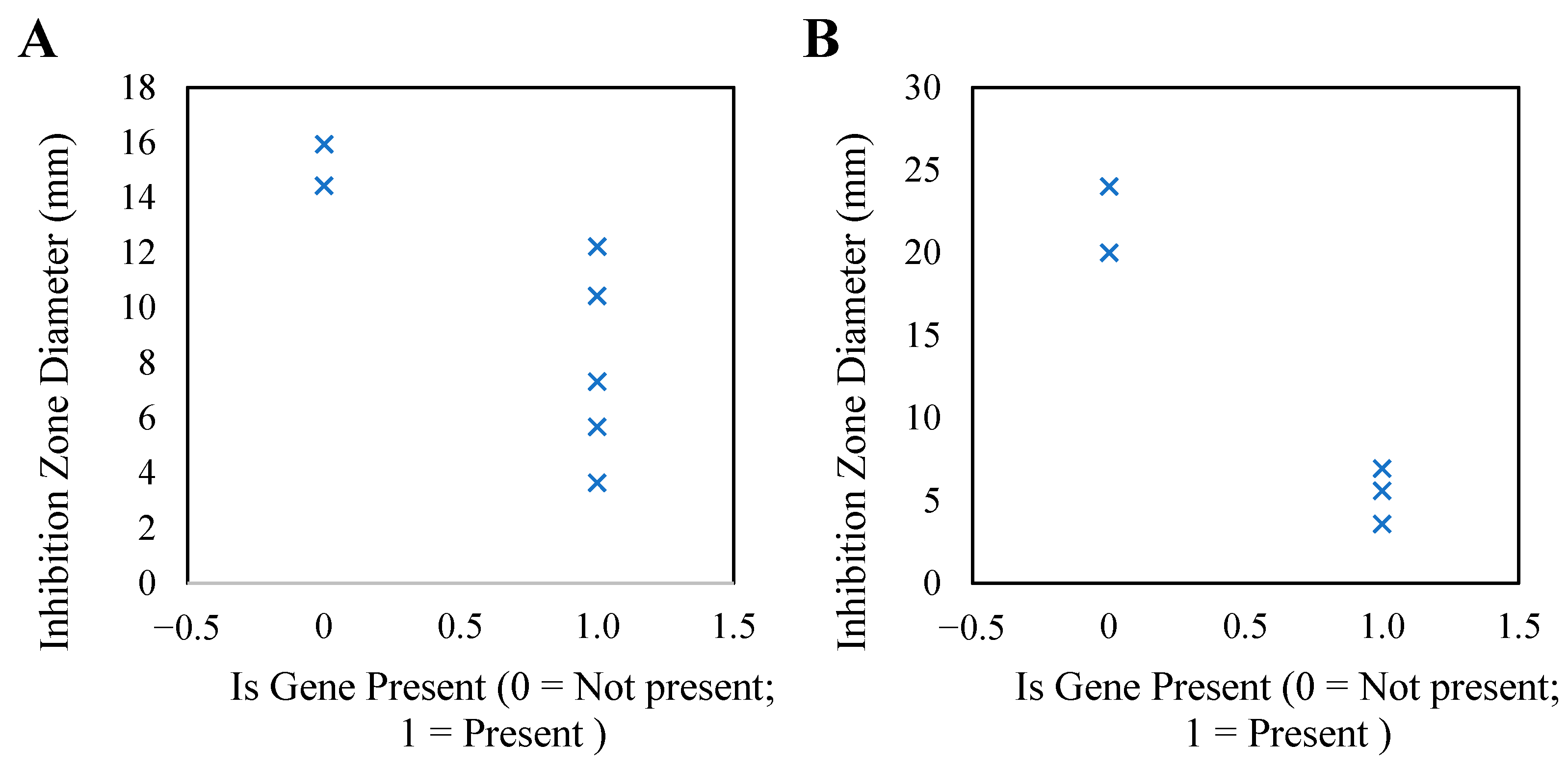

3.5.2. Association Analysis Between Genotype and Phenotype Drug Resistance

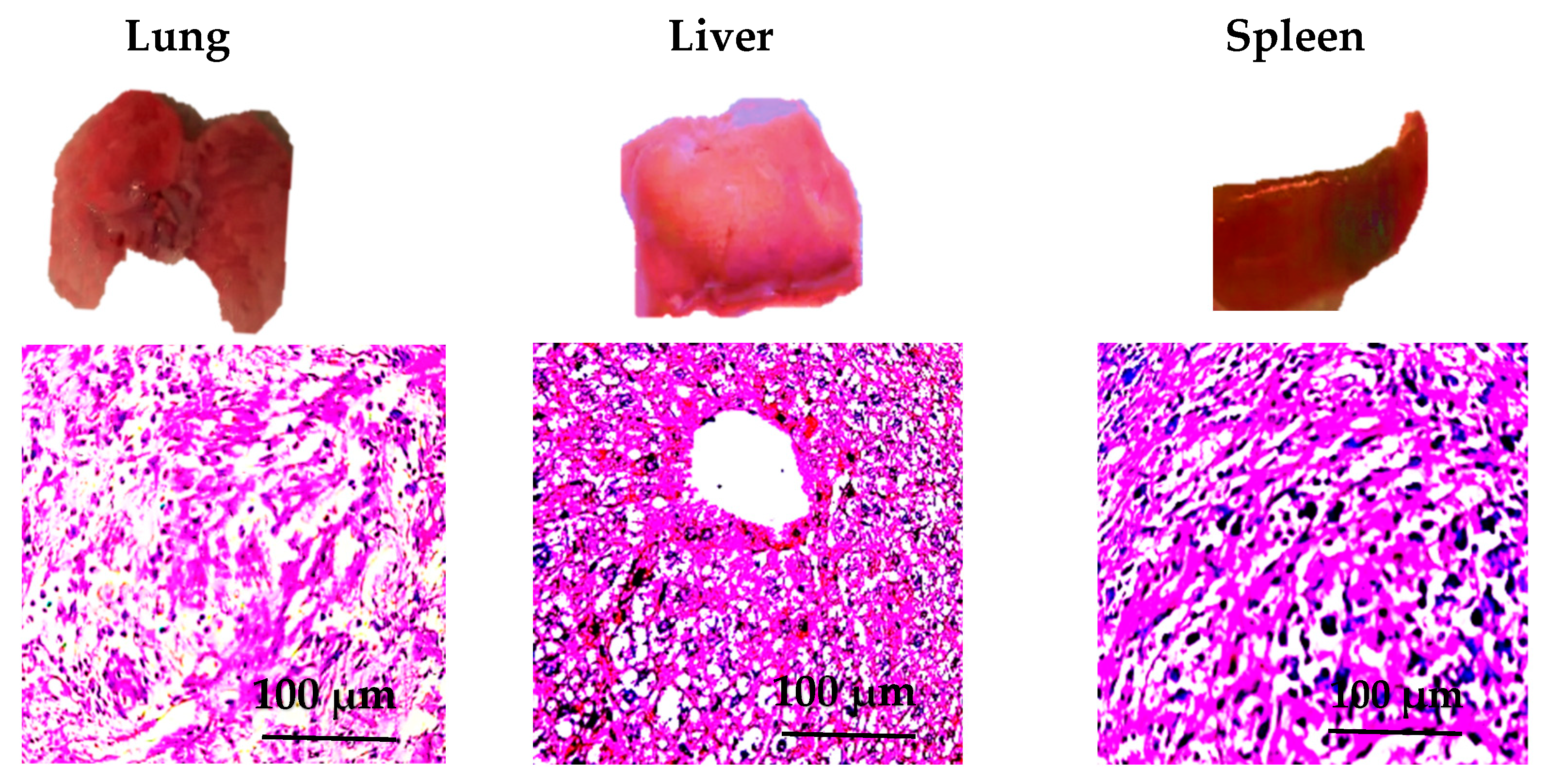

3.6. Pathogenicity Analysis

3.7. Pathological Observation Results

3.8. Correlation Analysis Between the Expression Levels of Virulence Genes and Pathogenicity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Angen, O.; Mutters, R.; Caugant, D.A.; Olsen, J.E.; Bisgaard, M. Taxonomic Relationships of the [Pasteurella] Haemolytica Complex as Evaluated by DNA-DNA Hybridizations and 16S rRNA Sequencing with Proposal of Mannheimia haemolytica Gen. Nov., Comb, Nov., Mannheimia granulomatis Comb. Nov., Mannheimia glucosida Sp. Nov., Mannheimia ruminalis Sp. Nov. and Mannheimia varigena Sp. Nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 1999, 49, 67–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dassanayake, R.P.; Clawson, M.L.; Tatum, F.M.; Briggs, R.E.; Kaplan, B.S.; Casas, E. Differential Identification of Mannheimia haemolytica Genotypes 1 and 2 Using Colorimetric Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification. BMC Res. Notes 2023, 16, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slate, J.R.; Chriswell, B.O.; Briggs, R.E.; McGill, J.L. The Effects of Ursolic Acid Treatment on Immunopathogenesis Following Mannheimia haemolytica Infections. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 782872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cozens, D.; Sutherland, E.; Lauder, M.; Taylor, G.; Berry, C.C.; Davies, R.L. Pathogenic Mannheimia haemolytica Invades Differentiated Bovine Airway Epithelial Cells. Infect. Immun. 2019, 87, e00078-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Rico, G.; Martinez-Castillo, M.; Avalos-Gómez, C.; De La Garza, M. Bovine Apo-Lactoferrin Affects the Secretion of Proteases in Mannheimia haemolytica A2. Access Microbiol. 2021, 3, 000269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Molecular Prevalence and Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Mannheimia haemolytica Isolated from Fatal Sheep and Goats Cases in Jiangsu, China. Pak. Vet. J. 2018, 38, 337–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Y.; Zhao, X.; Lei, J.; Ding, J.; Feng, H.; Wu, K.; Liu, J.; Wang, C.; Ye, D.; Wang, X.; et al. Characterization of Lung Microbiomes in Pneumonic Hu Sheep Using Culture Technique and 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing. Animals 2023, 13, 2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abed, A.H.; El-Seedy, F.R.; Hassan, H.M.; Nabih, A.M.; Khalifa, E.; Salem, S.E.; Wareth, G.; Menshawy, A.M.S. Serotyping, Genotyping and Virulence Genes Characterization of Pasteurella multocida and Mannheimia haemolytica Isolates Recovered from Pneumonic Cattle Calves in North Upper Egypt. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bkiri, D.; Semmate, N.; Boumart, Z.; Safini, N.; Fakri, F.Z.; Bamouh, Z.; Omari Tadlaoui, K.; Fellahi, S.; Tligui, N.; Fassi Fihri, O.; et al. Biological and Molecular Characterization of a Sheep Pathogen Isolate of Mannheimia haemolytica and Leukotoxin Production Kinetics. Vet. World 2021, 14, 2031–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clawson, M.L.; Schuller, G.; Dickey, A.M.; Bono, J.L.; Murray, R.W.; Sweeney, M.T.; Apley, M.D.; DeDonder, K.D.; Capik, S.F.; Larson, R.L.; et al. Differences between Predicted Outer Membrane Proteins of Genotype 1 and 2 Mannheimia haemolytica. BMC Microbiol. 2020, 20, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Ritchey, J.W.; Confer, A.W. Mannheimia haemolytica: Bacterial–Host Interactions in Bovine Pneumonia. Vet. Pathol. 2011, 48, 338–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, K.; Kim, D.H.; Park, H.-S.; Oh, M.H.; Lee, J.C.; Choi, C.H. Acinetobacter baumannii OmpA Hinders Host Autophagy via the CaMKK2-Reliant AMPK-Pathway. mBio 2025, 16, e03369-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nash, Z.M.; Inatsuka, C.S.; Cotter, P.A.; Johnson, R.M. Bordetella Filamentous Hemagglutinin and Adenylate Cyclase Toxin Interactions on the Bacterial Surface Are Consistent with FhaB-Mediated Delivery of ACT to Phagocytic Cells. mBio 2024, 15, e00632-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silale, A.; Van Den Berg, B. TonB-Dependent Transport Across the Bacterial Outer Membrane. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 77, 67–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, Y.; Gong, J.; Zhang, J.; Su, Y.; Hu, C.; Li, T.; Wu, Y.; Jiang, M. Research Status of Soda Residue in the Field of Environmental Pollution Control. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 28975–28983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clawson, M.L.; Murray, R.W.; Sweeney, M.T.; Apley, M.D.; DeDonder, K.D.; Capik, S.F.; Larson, R.L.; Lubbers, B.V.; White, B.J.; Kalbfleisch, T.S.; et al. Genomic Signatures of Mannheimia haemolytica That Associate with the Lungs of Cattle with Respiratory Disease, an Integrative Conjugative Element, and Antibiotic Resistance Genes. BMC Genom. 2016, 17, 982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, J.; Calderón Bernal, J.M.; Torre-Fuentes, L.; Hernández, M.; Jimenez, C.E.P.; Domínguez, L.; Fernández-Garayzábal, J.F.; Vela, A.I.; Cid, D. Antimicrobial Susceptibility and Resistance Mechanisms in Mannheimia haemolytica Isolates from Sheep at Slaughter. Animals 2023, 13, 1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Ma, J.; Huo, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, H.; Shan, L.; Ma, X. Bioinformatics Identification of the Expression and Clinical Significance of E2F Family in Endometrial Cancer. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 557188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Yin, C.; Wang, G.; Rosenblum, J.; Krishnan, S.; Dimitrova, N.; Fallon, J.T. Optimizing a Metatranscriptomic Next-Generation Sequencing Protocol for Bronchoalveolar Lavage Diagnostics. J. Mol. Diagn. 2019, 21, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnal, J.L.; Fernández, A.; Vela, A.I.; Sanz, C.; Fernández-Garyzábal, J.F.; Cid, D. Capsular Type Diversity of Mannheimia haemolytica Determined by Multiplex Real-Time PCR and Indirect Hemagglutination in Clinical Isolates from Cattle, Sheep, and Goats in Spain. Vet. Microbiol. 2021, 258, 109121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasim, M.T.; Mahdi Mohammed Alakkam, E.; Mahdi Mohammed, M.; Hachim, S.K.; Sabah Jabr, H.; Emad Izzat, S.; Mohammed, K.A.; Hamood, S.A.; Shnain Ali, M.; Najd Obaid, F.; et al. Ovine Pasteurellosis Vaccine: Assessment of the Protective Antibody Titer and Recognition of the Prevailing Serotypes. Arch. Razi Inst. 2022, 77, 1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klima, C.L.; Zaheer, R.; Briggs, R.E.; McAllister, T.A. A Multiplex PCR Assay for Molecular Capsular Serotyping of Mannheimia haemolytica Serotypes 1, 2, and 6. J. Microbiol. Methods 2017, 139, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seemann, T. Prokka: Rapid Prokaryotic Genome Annotation. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2068–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minh, B.Q.; Schmidt, H.A.; Chernomor, O.; Schrempf, D.; Woodhams, M.D.; Von Haeseler, A.; Lanfear, R. IQ-TREE 2: New Models and Efficient Methods for Phylogenetic Inference in the Genomic Era. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2020, 37, 1530–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Alikhan, N.-F.; Sergeant, M.J.; Luhmann, N.; Vaz, C.; Francisco, A.P.; Carriço, J.A.; Achtman, M. GrapeTree: Visualization of Core Genomic Relationships among 100,000 Bacterial Pathogens. Genome Res. 2018, 28, 1395–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortolaia, V.; Kaas, R.S.; Ruppe, E.; Roberts, M.C.; Schwarz, S.; Cattoir, V.; Philippon, A.; Allesoe, R.L.; Rebelo, A.R.; Florensa, A.F.; et al. ResFinder 4.0 for Predictions of Phenotypes from Genotypes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2020, 75, 3491–3500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Z.; Jiang, J.; Meng, Y.; Wu, G.; Tang, J.; Chen, T.; Fu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Gao, H.; et al. Immune Cells in the Spleen of Mice Mediate the Inflammatory Response Induced by Mannheimia Haemolytica A2 Serotype. Animals 2024, 14, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahay, S.; Prajapati, A.; Shome, B.R.; Rahman, H.; Shome, R. Mapping Heterogeneous Population Structure of Mannheimia haemolytica Associated with Pneumonic Infection of Sheep in Southern State Karnataka, India. Curr. Microbiol. 2024, 81, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Shao, Z.; Dai, G.; Li, X.; Xiang, Y.; Jiang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Ren, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Fan, C.; et al. Pathogenic Infection Characteristics and Risk Factors for Bovine Respiratory Disease Complex Based on the Detection of Lung Pathogens in Dead Cattle in Northeast China. J. Dairy Sci. 2023, 106, 589–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemu, S.; Belachew, Y.; Tefera, T. Isolation and Molecular Detection of Mannheimia haemolytica and Pasteurella multocida from Clinically Pneumonic Pasteurellosis Cases of Bonga Sheep Breed and Their Antibiotic Susceptibility Tests in Selected Areas of Southwest Ethiopian Peoples Regional State, Ethiopia. Vet. Med. Res. Rep. 2023, 14, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, P.R. Treatment and Control of Respiratory Disease in Sheep. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Food Anim. Pract. 2011, 27, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodwin, K.; Jackson, R.; Brown, C.; Davies, P.; Morris, R.; Perkins, N. Pneumonic Lesions in Lambs in New Zealand: Patterns of Prevalence and Effects on Production. N. Z. Vet. J. 2004, 52, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Getnet, K.; Abera, B.; Getie, H.; Molla, W.; Mekonnen, S.A.; Megistu, B.A.; Abat, A.S.; Dejene, H.; Birhan, M.; Ibrahim, S.M. Serotyping and Seroprevalence of Mannheimia haemolytica, Pasteurella multocida, and Bibersteinia trehalosi and Assessment of Determinants of Ovine pasteurellosis in West Amhara Sub-Region, Ethiopia. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 866206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Mazón, L.; Ramírez-Rico, G.; De La Garza, M. Lactoferrin Affects the Viability of Bacteria in a Biofilm and the Formation of a New Biofilm Cycle of Mannheimia haemolytica A2. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benz, R.; Piselli, C.; Potter, A. Channel Formation by LktA of Mannheimia (Pasteurella) haemolytica in Lipid Bilayer Membranes and Comparison of Channel Properties with Other RTX-Cytolysins. Toxins 2019, 11, 604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaldis, A.; Uddin, M.S.; Guluarte, J.O.; Martin, C.; Alexander, T.W.; Menassa, R. Development of a Plant-Based Oral Vaccine Candidate against the Bovine Respiratory Pathogen Mannheimia haemolytica. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1251046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, J. RTX Toxins of Animal Pathogens and Their Role as Antigens in Vaccines and Diagnostics. Toxins 2019, 11, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharkey, L.K.R.; O’Neill, A.J. Antibiotic Resistance ABC-F Proteins: Bringing Target Protection into the Limelight. ACS Infect. Dis. 2018, 4, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharkey, L.K.R.; Edwards, T.A.; O’Neill, A.J. ABC-F Proteins Mediate Antibiotic Resistance through Ribosomal Protection. mBio 2016, 7, e01975-15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacoby, G.A. Mechanisms of Resistance to Quinolones. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2005, 41, S120–S126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, S.; Tajbakhsh, S.; Naeimi, B.; Yousefi, F. Investigation of gyrA and parC Mutations and the Prevalence of Plasmid-Mediated Quinolone Resistance Genes in Klebsiella Pneumoniae Clinical Isolates. BMC Microbiol. 2024, 24, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avakh, A.; Grant, G.D.; Cheesman, M.J.; Kalkundri, T.; Hall, S. The Art of War with Pseudomonas Aeruginosa: Targeting Mex Efflux Pumps Directly to Strategically Enhance Antipseudomonal Drug Efficacy. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zankari, E.; Hasman, H.; Cosentino, S.; Vestergaard, M.; Rasmussen, S.; Lund, O.; Aarestrup, F.M.; Larsen, M.V. Identification of Acquired Antimicrobial Resistance Genes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012, 67, 2640–2644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kherroubi, L.; Bacon, J.; Rahman, K.M. Navigating Fluoroquinolone Resistance in Gram-Negative Bacteria: A Comprehensive Evaluation. JAC-Antimicrob. Resist. 2024, 6, dlae127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitondo-Silva, A.; Martins, V.V.; Silva, C.F.D.; Stehling, E.G. Conjugation between Quinolone-Susceptible Bacteria Can Generate Mutations in the Quinolone Resistance-Determining Region, Inducing Quinolone Resistance. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2015, 45, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Li, Z.; Wei, W.; Ma, C.; Song, X.; Li, S.; He, W.; Tian, J.; Huo, X. Association of Mutation Patterns in GyrA and ParC Genes with Quinolone Resistance Levels in Lactic Acid Bacteria. J. Antibiot. 2015, 68, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, M.; Mani, R.; Sreevatsan, S. Genome Sequences of Seven Mannheimia haemolytica Isolates from Feedlots in Oklahoma and California. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 2024, 13, e00785-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahay, S.; Natesan, K.; Prajapati, A.; Kalleshmurthy, T.; Shome, B.R.; Rahman, H.; Shome, R. Prevalence and Antibiotic Susceptibility of Mannheimia haemolytica and Pasteurella multocida Isolated from Ovine Respiratory Infection: A Study from Karnataka, Southern India. Vet. World 2020, 13, 1947–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, P.K.; Shanthalingam, S.; Dassanayake, R.P.; Subramaniam, R.; Herndon, C.N.; Knowles, D.P.; Rurangirwa, F.R.; Foreyt, W.J.; Wayman, G.; Marciel, A.M.; et al. Transmission of Mannheimia haemolytica from domestic sheep (Ovis aries) to bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis): Unequivocal demonstration with green fluorescent protein-tagged organisms. J. Wildl. Dis. 2010, 46, 706–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragkou, I.A.; Gougoulis, D.A.; Billinis, C.; Mavrogianni, V.S.; Bushnell, M.J.; Cripps, P.J.; Tzora, A.; Fthenakis, G.C. Transmission of Mannheimia haemolytica from the Tonsils of Lambs to the Teat of Ewes during Sucking. Vet. Microbiol. 2011, 148, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-Q.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Z.-Y.; Wu, Y.-J.; Chen, X.; Zhang, M.-Y.; Zhuang, Z.-J.; He, A.-B.; Zhang, S.-X.; Xu, Q.; et al. IFI204 Restricts Mannheimia haemolytica Pneumonia via Eliciting Gasdermin D-Dependent Inflammasome Signaling. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayalew, S.; Confer, A.W.; Payton, M.E.; Garrels, K.D.; Shrestha, B.; Ingram, K.R.; Montelongo, M.A.; Taylor, J.D. Mannheimia haemolytica Chimeric Protein Vaccine Composed of the Major Surface-Exposed Epitope of Outer Membrane Lipoprotein PlpE and the Neutralizing Epitope of Leukotoxin. Vaccine 2008, 26, 4955–4961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, K.A.; MacGlover, C.A.W.; Blecha, K.A.; Stenglein, M.D. Assessing Shared Respiratory Pathogens between Domestic (Ovis Aries) and Bighorn (Ovis Canadensis) Sheep; Methods for Multiplex PCR, Amplicon Sequencing, and Bioinformatics to Characterize Respiratory Flora. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0293062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Rico, G.; Ruiz-Mazón, L.; Reyes-López, M.; Rivillas Acevedo, L.; Serrano-Luna, J.; De La Garza, M. Apo-Lactoferrin Inhibits the Proteolytic Activity of the 110 kDa Zn Metalloprotease Produced by Mannheimia haemolytica A2. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omaleki, L.; Barber, S.R.; Allen, J.L.; Browning, G.F. Mannheimia Species Associated with Ovine Mastitis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2010, 48, 3419–3422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharib Mombeni, E.; Gharibi, D.; Ghorbanpoor, M.; Jabbari, A.R.; Cid, D. Molecular Characterization of Mannheimia haemolytica Associated with Ovine and Caprine Pneumonic Lung Lesions. Microb. Pathog. 2021, 153, 104791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 35892-2018; Laboratory Animal—Guideline for Ethical Review of Animal Welfare. Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2018.

| Gene | Serotype | Sequence | DNA Fragment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hyp | A1 | F: 5′-CATTTCCTTAGGTTCAGC-3′ | 306 bp |

| R: 5′-CAAGTCATCGTAATGCCT-3′ | |||

| Core2 | A2 | F: 5′-GGCATATCCTAAAGCCGT-3′ | 160 bp |

| R: 5′-AGAATCCACTATTGGGCACC-3′ | |||

| TupA | A6 | F: 5′-TGAGAATTTCGACAGCACT-3′ | 78 bp |

| R: 5′-ACCTTGGCATATCGTACC-3′ |

| Isolate | Region | Source | Serotype | Accession Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MH1 | Shaanxi | Ovine | A2 | SAMN52441444 |

| MH2 | Gansu | Ovine | A6 | SAMN52441445 |

| MH3 | Shaanxi | Ovine | A1 | SAMN52441446 |

| MH4 | Shaanxi | Ovine | A1 | SAMN52441447 |

| MH5 | Shaanxi | Ovine | A2 | SAMN52441448 |

| MH6 | Shaanxi | Ovine | A2 | SAMN52441449 |

| MH7 | Shaanxi | Ovine | A2 | SAMN52441450 |

| MH8 | Ningxia | Ovine | A1 | SAMN52441451 |

| MH9 | Gansu | Ovine | A2 | SAMN52441452 |

| Antibiotic | Sensitivity (%) | Intermediate (%) | Mean Inhibition Zone Diameter (mm) ± SD | Resistant (%) | Associated Resistance Gene |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ciprofloxacin | 8 (88.89) | 0 (0.00) | 17.64 ± 1.25 | 1 (11.11) | qnr |

| Azithromycin | 8 (88.89) | 0 (0.00) | 16.36 ± 1.83 | 1 (11.11) | ermB |

| Gentamicin | 9 (100) | 0 (0.00) | 18.54 ± 1.02 | 0 (0.00) | aac(6′)-Ib |

| Levofloxacin | 9 (100) | 0 (0.00) | 17.86 ± 1.12 | 0 (0.00) | qnrA |

| Tiamulin | 1 (11.11) | 1 (11.11) | 8.25 ± 2.48 | 7 (77.78) | vgaA |

| Enrofloxacin | 3 (33.33) | 1 (11.11) | 9.13 ± 2.72 | 5 (55.56) | gyrA |

| Group | Total | Number of Pathological Manifestations | Proportion (%) | Number of Deaths | Mortality Rate (%) | Elevated Body Temperature | Shortness of Breath | Reduced Activities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shaanxi | 10 | 10 | 100 | 10 | 100 | 9 | 10 | 8 |

| Gansu | 10 | 10 | 100 | 8 | 80 | 8 | 10 | 5 |

| Ningxia | 10 | 10 | 100 | 6 | 60 | 8 | 9 | 4 |

| Total | 30 | 30 | 100 | 24 | 80% | 25 | 29 | 17 |

| Gene | Infected Group (n = 24) | Control Group (n = 6) | Expression Fold Change | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| lktA | 8.1 ± 0.5 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 8.1 | <0.01 |

| tonB | 4.5 ± 0.4 | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 4.5 | <0.05 |

| sodA | 3.2 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 3.2 | <0.05 |

| Gene | Clinical Symptom Correlation (r) | Correlation of Pathological Changes (r) | Mortality Correlation (r) | Pathogenicity Explanation Ratio (R2) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| lktA | 0.78 (Difficulty breathing and reduced activity) | 0.82 (Pulmonary necrosis, inflammatory infiltration) | 0.85 | 65% | <0.01 |

| tonB | 0.60 (Elevated body temperature) | 0.68 (Liver congestion and edema) | 0.55 | 30% | <0.05 |

| sodA | 0.65 (Inflammatory cell infiltration) | 0.63 (Oxidative stress response) | 0.5 | 25% | <0.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, C.; Dou, L.; Wang, J.; Ye, D.; Yang, Z. Molecular Epidemiology and Antibiotic Resistance of Sheep-Derived Mannheimia haemolytica in Northwestern China. Animals 2025, 15, 3492. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233492

Wang C, Dou L, Wang J, Ye D, Yang Z. Molecular Epidemiology and Antibiotic Resistance of Sheep-Derived Mannheimia haemolytica in Northwestern China. Animals. 2025; 15(23):3492. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233492

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Chenxiao, Leina Dou, Juan Wang, Dongyang Ye, and Zengqi Yang. 2025. "Molecular Epidemiology and Antibiotic Resistance of Sheep-Derived Mannheimia haemolytica in Northwestern China" Animals 15, no. 23: 3492. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233492

APA StyleWang, C., Dou, L., Wang, J., Ye, D., & Yang, Z. (2025). Molecular Epidemiology and Antibiotic Resistance of Sheep-Derived Mannheimia haemolytica in Northwestern China. Animals, 15(23), 3492. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233492