Acoustic Diversity in Zhangixalus lishuiensis: Intra-Individual Variation, Acoustic Divergence, and Genus-Level Comparisons

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

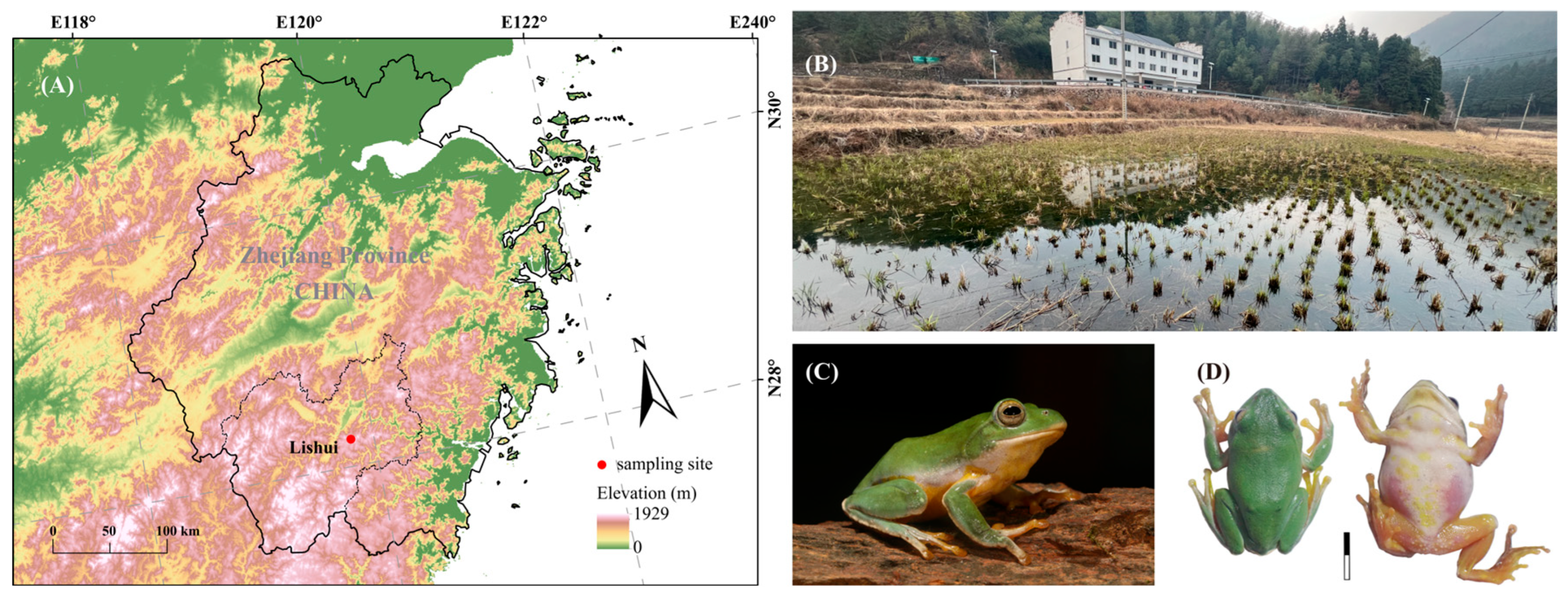

2.1. Study Site and Recordings

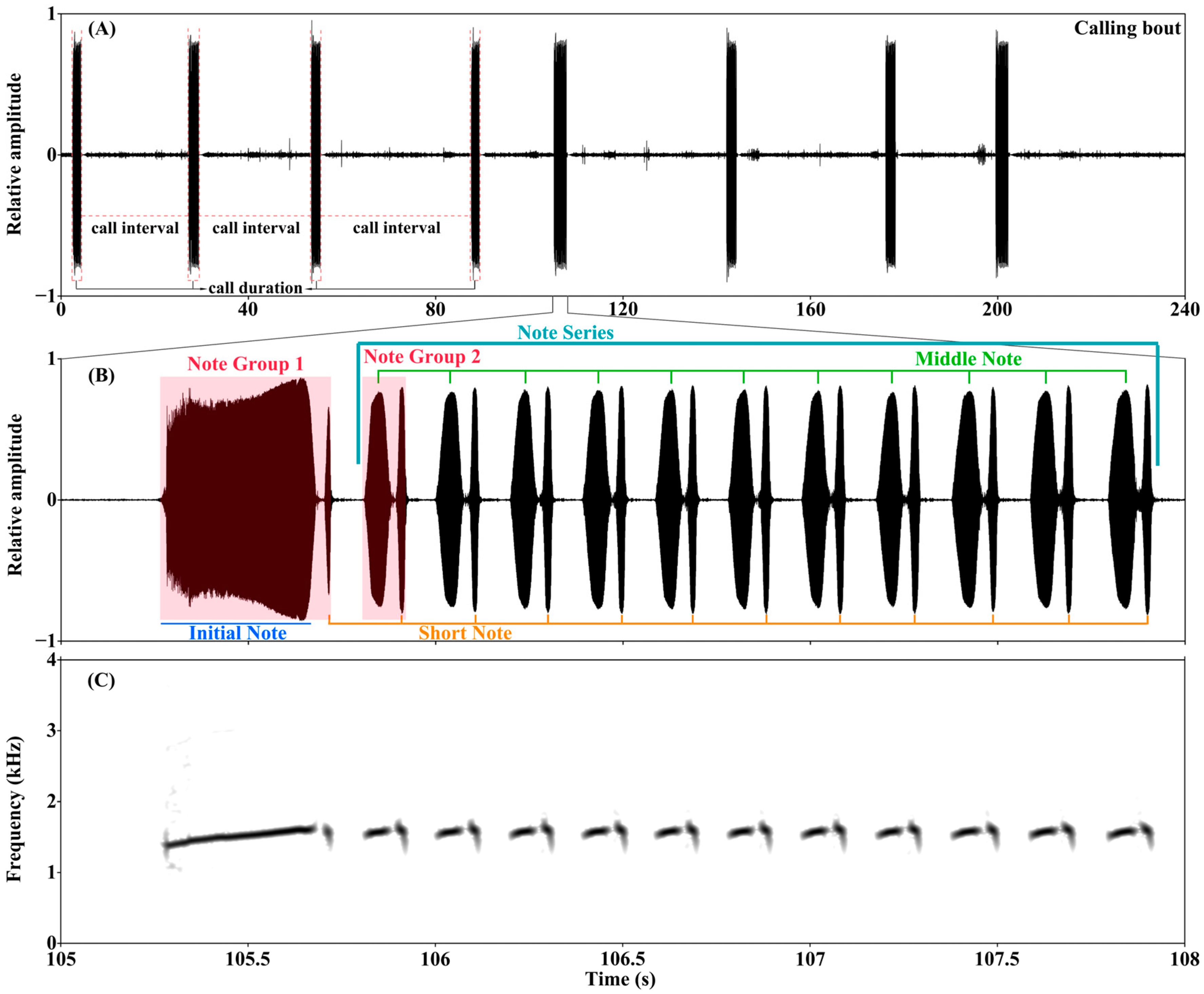

2.2. Acoustic Analysis

2.3. Statistical Analysis

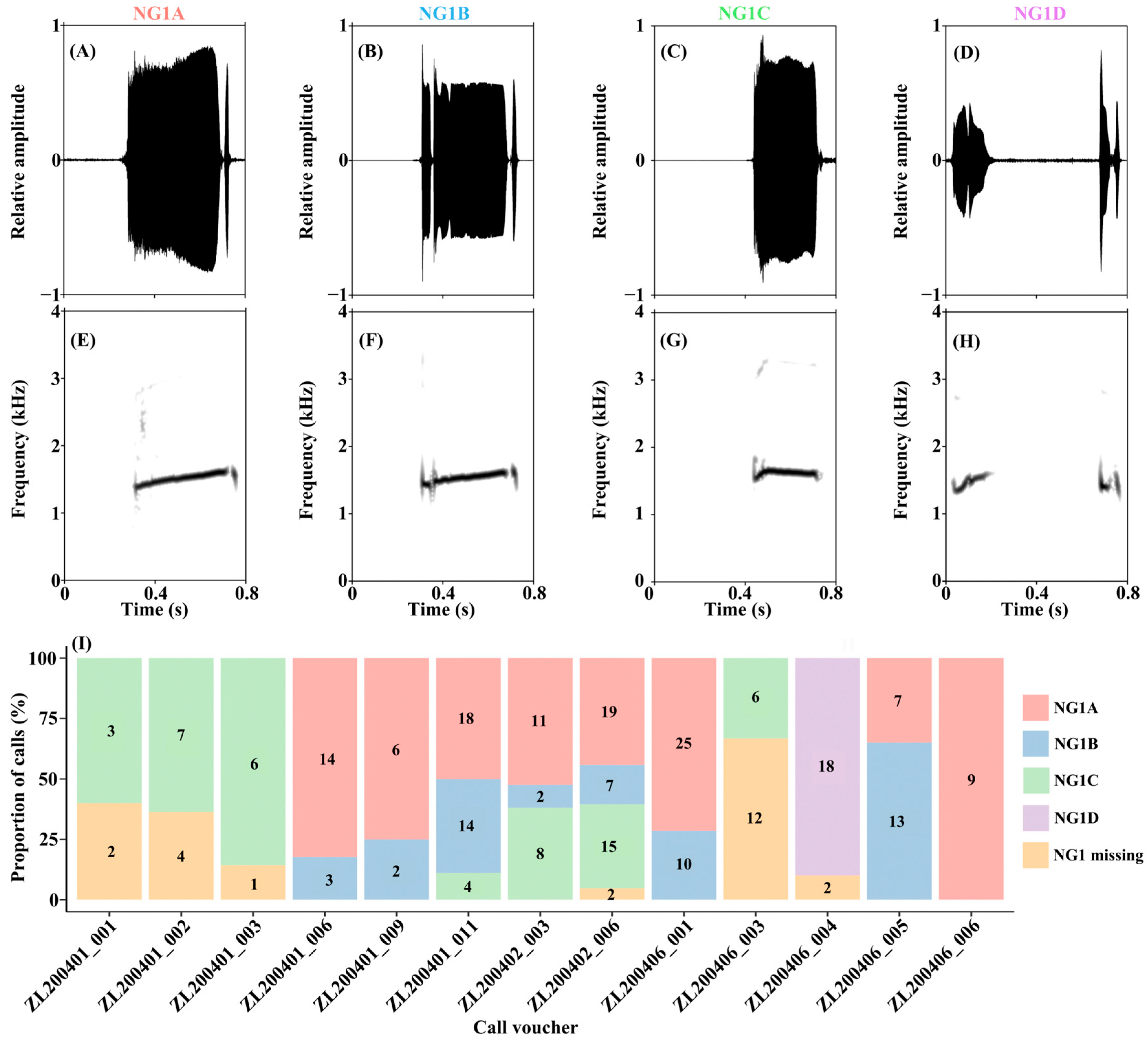

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Acoustic Diversity in Z. lishuiensis and Its Potential Functions

4.2. Acoustic Divergence Between Z. lishuiensis and Z. zhoukaiyae

4.3. Call Diversity in the Genus Zhangixalus

4.4. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CD | Call duration |

| CI | Call interval |

| DF | Dominant frequency |

| DNG1 | Duration of Note Group 1 |

| DNG2 | Mean duration of Note Group 2 |

| DNS | Duration of Note Series |

| FFT | Fast Fourier transform |

| ING12 | Interval between Note Group 1 and 2 |

| ING22 | Mean interval between two Note Group 2 |

| NG1 | Note Group 1 (first note group) |

| NG2 | Note Group 2 (second note group) |

| NNG2 | Number of Note Group 2 |

| NS | Note Series |

| NA | Not applicable |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| SVL | Snout–vent length |

References

- Jin, Y.J.; Zhao, L.H.; Qin, Y.Y.; Wang, J.C. Diversity of anurans in the Bawangling Area of Hainan National Park based on auto-recording technique. Biodiver. Sci. 2023, 31, 22360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, R.R.; Shen, T.; Li, H.; Tian, L.C.; Tan, H.R.; Lu, L.R.; Wu, X.G.; Fan, Z.J.; Wu, G.Y.; Li, J.; et al. A dataset of call characteristics of anuran from the Chebaling National Nature Reserve, Guangdong Province. Biodiver. Sci. 2024, 32, 24356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, Q.; Wang, C.; Hao, Z.Z. Application of ecoacoustic monitoring in the field of biodiversity science. J. Appl. Ecol. 2021, 32, 1119–1128. [Google Scholar]

- Guerra, V.; Llusia, D.; Gambale, P.G.; de Morais, A.R.; Márquez, R.; Bastos, R.P. The advertisement calls of Brazilian anurans: Historical review, current knowledge and future directions. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0191691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, Y.Z.; Zeng, Y.W.; Zheng, P.Y.; Liao, X.; Xie, F. Structural and bio-functional assessment of the postaxillary gland in Nidirana pleuraden (Amphibia: Anura: Ranidae). Zool. Lett. 2020, 6, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, K.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, J.X.; Wang, T.L.; Wang, J.C.; Cui, J.G. Hainan frilled treefrogs adjust spectral traits to increase competitiveness when perceiving conspecific disturbance odours. Anim. Biol. 2025, 222, 123032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechelt, S.; HöDL, W.; RingLER, M.A. The Role of spectral advertisement call properties in species recognition of male Allobates talamancae (Cope, 1875). Herpetozoa 2014, 26, 139–150. [Google Scholar]

- Manzano, M.C.R.; Takeno, M.F.; Sawaya, R.J. Advertisement calls of 18 anuran species in the megadiverse atlantic forest in Southeastern Brazil: Review and update. Zootaxa 2022, 5178, 453–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bee, M.A.; Perril, L.S.A. Responses to conspecific advertisement calls in the green frog (Rana clamitans) and their role in male-male communication. Behaviour 1996, 133, 283–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.M.; Deng, K.; Wang, T.L.; Wang, J.C.; Cui, J.G. Attracting mates or suppressing rivals? Distance-dependent calling strategy in Hainan frilled treefrogs. Anim. Behav. 2025, 219, 123033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerhardt, H.C.; Huber, F. Acoustic Communication in Insects and Anurans: Common Problems and Diverse Solutions; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, H.L.; Feng, L.; Zhang, C.Y.; Xiang, Z.Y.; Hao, J.J.; Zhou, J.; Ding, G.H. Environmental and morphological determinants of advertisement call variability in a moustache toad. Asian. Herpetol. Res. 2025, 16, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufresnes, K.; Mazepa, G.; Jablonski, D.; Oliveira, R.K.; Wenceliers, T.; Shabanov, D.A.; Auer, M.; Ernst, R.; Koch, S.; Ramirez-Chavez, H.E.; et al. Fifteen shades of green: The revised evolution of bufotes toads. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2019, 141, 106615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.Q.; Li, S.Z.; Liu, W.; Wang, B.; Wu, J. Description of a new horned toad of Megophrys Kuhl & Van Hasselt, 1822 (Amphibia, Megophryidae) from Zhejiang Province, China. ZooKeys 2020, 1005, 73–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.Q.; Lin, Y.F.; Tang, Y.; Ding, G.H.; Wu, Y.Q.; Lin, Z.H. Acoustic divergence in advertisement calls among three sympatric Microhyla species from East China. PeerJ 2020, 8, e8708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, J.; Jansen, M.; Rodríguez, A.; Kok, P.J.R.; Toledo, L.F.; Emmrich, M.; Glaw, F.; Haddad, C.F.B.; Rödel, M.-O.; Vences, M. The Use of bioacoustics in anuran taxonomy: Theory, terminology, methods and recommendations for best practice. Zootaxa 2017, 4732, 1–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, D.C.; Jiang, K.; Ren, J.L.; Wu, J.; Li, J.T. Resurrection of the genus Leptomantis, with description of a new genus to the family Rhacophoridae (Amphibia: Anura). Asian. Herpetol. Res. 2019, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Frost, D.R. Amphibian Species of the World: An Online Reference. Version 6.0. American Museum of Natural History: New York, NY, USA. Available online: http://research.amnh.org/herpetology/amphibia/index.php/ (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- AmphibiaChina. The Database of Chinese Amphibians. Kunming Institute of Zoology (CAS): Kunming, China. Available online: http://www.amphibiachina.org/ (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Xu, J.X.; Xie, F.; Jiang, J.P.; Mo, Y.M.; Zheng, Z.H. The acoustic features of the mating call of 12 anuran species. Chin. J. Zool. 2005, 40, 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.C.; Cui, J.G.; Shi, H.T.; Brauth, S.E.; Tang, Y.Z. Effects of body size and environmental factors on the acoustic structure and temporal rhythm of calls in Rhacophorus dennysi. Asian. Herpetol. Res. 2012, 3, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, M.; Wu, G.F. Acoustic characteristics of treefrogs from Sichuan, China, with comments on systematic relationship of Polypedates and Rhacophorus (Anura, Rhacophoridae). Zool. Sci. 1994, 11, 485–490. [Google Scholar]

- Mo, Y.M.; Chen, W.C.; Liao, X.W.; Zhou, S.C. A new species of the Genus Rhacophorus (Anura: Rhacophoridae) from Southern China. Asian. Herpetol. Res. 2016, 7, 139–150. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, K.; Zhang, B.W.; Brauth, S.E.; Tang, Y.Z.; Fang, G.Z. The First call note of the Anhui Tree Frog (Rhacophorus zhoukaiya) is acoustically suited for enabling individual recognition. Bioacoustics 2019, 28, 155–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibnudarda, R.; Munir, M.; Gonggoli, A.D.; Hamidi, A. Features of the call signs of Zhangixalus frogs from Southeast Asia with a new call sign profile for Zhangixalus faristsalhadii frogs from Central Java, Indonesia (Anuran: Rhacophoridae). Zootaxa 2025, 5660, 297–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Constructing the Acoustic Data Base of Taiwan’s Wildlife. Available online: http://www.taisong.org/index.php/ (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- China National Specimen Information Infrastructure (NSII). Available online: https://www.nsii.org.cn/2017/AnuraVoice.php/ (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Ding, G.H.; Hu, H.L.; Chen, J.Y. A Feild Guide to the Amphibians of Eastern China; China Agricultural Science and Technology Press: Beijing, China, 2022; p. 139. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, T.; Zhang, Y.N.; Wang, H.; Wu, J.; Kang, X.; Qian, L.F.; Li, K.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.Y.; Rao, D.Q.; et al. A new species of the Genus Rhacophorus (Anura: Rhacophoridae) from Dabie Mountains in East China. Asian. Herpetol. Res. 2017, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.Q.; Wang, Y.F.; Jiang, K.; Chen, H.M.; Zhou, J.J.; Xu, J.N.; Wu, C.H. A New Treefrog species of the Genus Rhacophorus found in Zhejiang, China (Anura: Rhacophoridae). Chin. J. Zool. 2017, 52, 361–372. [Google Scholar]

- Dufresnes, C.; Litvinchuk, S.N. Diversity, Distribution and molecular species delimitation in frogs and toads from the Eastern Palaearctic. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 2022, 195, 695–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brakels, P.; Nguyen, T.V.; Pawangkhanant, P.; Idiiatullina, S.S.; Lorphengsy, S.; Suwannapoom, C.; Poyarkov, N.A. Mountain jade: A new high-elevation microendemic species of the genus Zhangixalus (Amphibia: Anura: Rhacophoridae) from Laos. Zool. Res. 2023, 44, 374–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.Q.; Huang, J.K.; Zhou, J.Q.; Lu, W.Z.; Zhou, J.J.; Wang, Y.F.; Zhou, L.M.; Chen, L.H. New subspecies of Zhangixalus (Class: Amphibia, Order: Anura, Family: Rhacophoridae): Zhangixalus taipeianus jingningensis. Chin. J. Wildlife 2024, 45, 912–920. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Y.Q.; Liu, S.; Chen, J.; Yu, G.H. Underestimated species diversity in Zhangixalus (Anura, Rhacophoridae) with a description of two cryptic species from southern China. Zoosyst. Evol. 2025, 101, 485–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, G.; Zwitzers, B.; Than, N.L.; Gupta, D.K.; Janke, A.; Pauls, S.U.; Thammachoti, P. Bioacoustics reveal hidden diversity in frogs: Two new species of the genus Limnonectes from Myanmar (Amphibia, Anura, Dicroglossidae). Diversity 2021, 13, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boersma, P.; Weenink, D. Praat: Doing Phonetics by Computer, Version 6.4.127. 2025. Available online: http://www.praat.org/ (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Yue, X.Z.; Fan, Y.Z.; Xue, F.; Brauth, S.E.; Tang, Y.Z.; Fang, G.Z. The first call note plays a crucial role in frog vocal communication. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 10128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Q.Y.; Sun, R.L.; Wang, Z.Y.; Song, J.J.; Fang, K.; Zhang, B.W.; Fang, G.Z. The first two functionally antagonistic call notes influence female choice in the Anhui Tree Frog. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2024, 78, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seebaa, F.; Schwartzb, J.J.; Bee, M.A. Testing an auditory illusion in frogs: Perceptual restoration or sensory bias? Anim. Behav. 2010, 79, 1317–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalra, L.; Bee, M. Auditory streaming and rhythmic masking release in Cope’s Gray Treefrog. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2025, 157, 2319–2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vélez, A.; Schwartz, J.J.; Bee, M.A. Anuran acoustic signal perception in noisy environments. In Animal Communication and Noise; Brumm, H., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 133–186. [Google Scholar]

- Gingras, B.; Böckle, M.; Herbst, C.T.; Fitch, W.T. Call acoustics reflect body size across four clades of anurans. J. Zool. 2013, 289, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stănescu, F.; Márquez, R.; Cogălniceanu, D.; Marangoni, F. Older males whistle better: Age and body size are encoded in the mating calls of a nest-building amphibian (Anura: Leptodactylidae). Front. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 10, 1020613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humfeld, S.C.; Grunert, B. Effects of temperature on spectral preferences of female gray treefrogs (Hyla versicolor). Herpetol. Conserv. Biol. 2015, 10, 1013–1020. [Google Scholar]

- Narins, P.M.; Meenderink, S.W.F. Climate change and frog calls: Long-term correlations along a tropical altitudinal gradient. Proc. R. Soc. B 2014, 281, 20140401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, L.; Arim, M.; Bozinovic, F. Intraspecific scaling in frog calls: The interplay of temperature, body size and metabolic condition. Oecologia 2016, 181, 673–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos-Franceschi, A.; Joglar, R.; Thomas, R. Variation in bioacoustics characteristics in Eleutherodactylus coqui Thomas, 1966 and Eleutherodactylus antillensis (Reinhardt and Lutken, 1863) (Anura: Eleutherodactylidae) in the Puerto Rico Bank. Life: Excit. Biol. 2019, 7, 82–114. [Google Scholar]

- Wycherley, J.; Doran, S.; Beebee, T.J.C. Frog calls echo microsatellite phylogeography in the European Pool Frog (Rana lessonae). J. Zool. 2002, 258, 479–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, M.R.; Seddon, N.; Safran, R.J. Evolutionary divergence in acoustic signals: Causes and consequences. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2013, 28, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.H.; Santos, J.C.; Wang, J.C.; Ran, J.H.; Tang, Y.Z.; Cui, J.G. Noise constrains the evolution of call frequency contours in flowing water frogs: A comparative analysis in two clades. Front. Zool. 2021, 18, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francis, C.D.; Phillips, J.N.; Barber, J.R. Background acoustics in terrestrial ecology. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2023, 54, 351–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Note 1 | Note 2 | Note 3 | Note 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Note 1 | ND: 0.323 ± 0.061 s DF: 1.53 ± 0.11 kHz | t = 13.87, adjusted p < 0.001 | t = 14.83, adjusted p < 0.001 | t = 14.44, adjusted p < 0.001 |

| Note 2 | t = −2.97, adjusted p = 0.124 | ND: 0.022 ± 0.003 s DF: 1.58 ± 0.12 kHz | t = −6.35, adjusted p < 0.01 | t = −2.12, adjusted p = 0.430 |

| Note 3 | t = −4.30, adjusted p = 0.022 | t = 0.13, adjusted p = 1.000 | ND: 0.047 ± 0.010 s DF: 1.58 ± 0.10 kHz | t = 7.47, adjusted p < 0.001 |

| Note 4 | t = −6.59, adjusted p < 0.01 | t = −3.10, adjusted p = 0.104 | t = −5.16, adjusted p < 0.01 | ND: 0.025 ± 0.004 s DF: 1.60 ± 0.11 kHz |

| Type | N | CD (s) | DNG1 (s) | ING12 (s) | NNG2 | DNG2 (s) | ING22 (s) | DNS (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NG1A | 109 | 2.258 ± 0.794 a 0.815–3.632 | 0.373 ± 0.069 c 0.185–0.529 | 0.077 ± 0.022 c 0.017–0.124 | 10.9 ± 3.3 a 4–17 | 0.092 ± 0.015 ab 0.050–0.113 | 0.079 ± 0.021 b 0.032–0.115 | 1.983 ± 0.758 a 0.678–3.303 |

| NG1B | 51 | 2.177 ± 0.580 a 1.309–3.530 | 0.436 ± 0.083 b 0.213–0.553 | 0.080 ± 0.020 c 0.027–0.104 | 9.8 ± 2.9 ab 5–17 | 0.096 ± 0.016 a 0.056–0.111 | 0.083 ± 0.017 b 0.041–0.112 | 1.824 ± 0.530 a 1.075–3.041 |

| NG1C | 49 | 1.500 ± 0.532 b 0.632–3.197 | 0.307 ± 0.079 d 0.178–0.544 | 0.108 ± 0.056 a 0.011–0.179 | 7.7 ± 2.9 c 3–14 | 0.087 ± 0.019 bc 0.0366–0.125 | 0.067 ± 0.026 c 0.021–0.113 | 1.242 ± 0.484 b 0.402–2.871 |

| NG1D | 18 | 2.325 ± 0.409 a 1.567–3.021 | 0.754 ± 0.040 a 0.711–0.879 | 0.102 ± 0.012 b 0.092–0.140 | 8.8 ± 2.4 bc 4–13 | 0.087 ± 0.008 bc 0.061–0.094 | 0.089 ± 0.006 ab 0.082–0.110 | 1.635 ± 0.430 a 0.742–2.362 |

| NG1 missing | 23 | 1.626 ± 0.651 b 0433–3.229 | NA | NA | 9.4 ± 5.9 b 2–29 | 0.083 ± 0.012 c 0.051–0.095 | 0.093 ± 0.017 a 0.042–0.125 | 1.626 ± 0.652 a 0.433–3.229 |

| Statistical results | χ2 = 49.4, p < 0.001 | χ2 = 94.7, p < 0.001 | χ2 = 32.0, p < 0.001 | χ2 = 30.2, p < 0.001 | χ2 = 19.2, p < 0.001 | χ2 = 23.3, p < 0.001 | χ2 = 41.0, p < 0.001 | |

| Acoustic Parameters | Z. lishuiensis (n = 13) (This Study) | Z. zhoukaiyae (n = 41) (Fang et al. [24]) | Statistical Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| CI (s) | 22.8 ± 16.1 | NA | |

| CD (s) | 1.96 ± 0.49 | 2.31 ± 0.65 | t = −2.06, p = 0.044 |

| DF (kHz) | 1.515 ± 0.083 | 1.574 ± 0.023 | t = −2.53, p = 0.014 |

| DNG1 (s) | 0.383 ± 0.129 | 0.196 ± 0.039 | t = 5.15, p < 0.001 |

| ING12 (s) | 0.105 ± 0.040 | 0.048 ± 0.017 | t = 5.00, p < 0.001 |

| NNG2 | 9.1 ± 2.1 | 19.0 ± 4.7 | t = −10.57, p < 0.001 |

| DNG2 (s) | 0.093 ± 0.013 | 0.064 ± 0.002 | t = 8.01, p < 0.001 |

| ING22 (s) | 0.084 ± 0.017 | 0.047 ± 0.001 | t = 7.84, p < 0.001 |

| Species [Reference] | Recording Site | CD (s) | DF (kHz) | AT (°C) | SVL (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Z. achantharrhena [25] | Mt. Singgalang, Balingka, West Sumatra, Indonesia | 0.3 ± 0.01 | 1.638–2.679 | NA | NA |

| Z. chenfui [20] | Daiguocao, Mount Wawu, Sichuan Province, China | 0.418 ± 0.055 | 2.00 ± 0.08 | 17.6 | NA |

| Z. chenfui [22] | Mt. Emei-shan, Sichuan Province, China | 0.158–0.645 | 2.100–2.3488 | 13.0 | NA |

| Z. dennysi [21] | Mt. Diaoluo National Nature Reserve, Hainan Province, China | 0.2355 | 1.268 ± 0.076 | NA | 87.6 ± 5.3 |

| Z. dugritei [20] | Daiguocao, Mount Wawu, Sichuan Province, China | 1.238 ± 0.046 | 1.70 ± 0.05 | 13–16 | NA |

| Z. dugritei [22] | Mt. Wa-shan, Sichuan Province, China | 0.075–1.015 | 1.45–2.5 | 4.0–8.0 | NA |

| Z. dulitensis [25] | Ulu Temburong National Park, Brunei | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 1.549–3.336 | NA | NA |

| Z. faritsalhadii [25] | Mt. Slamet, Kalipagu, Ketenger Village, Central Java Province, Indonesia | 0.1 ± 0.04 | 1.338–1.581 | 19.5–20.2 | 37.6 |

| Z. lishuiensis (this study) | Liandu Fengyuan Provincial Nature Reserve, Lishui, Zhejiang Province, China | 1.96 ± 0.49 | 1.515 ± 0.083 | 7.0–7.8 | 34.2–36.2 |

| Z. omeimontis [22] | Mt. Emei-shan, Sichuan Province, China | 0.166–0.460 | 0.828–0.977 | 11.0–13.0 | NA |

| Z. pinglongensis [23] | Shiwandashan National Nature Reserve, Guangxi Province, China | 0.43–0.47 | 1.6–3.0 | 18.4 | 38.2 |

| Z. prominanus [25] | Telekom Loop, Fraser’s Hill, Pahang, Malaysia | 0.1–0.4 | NA | NA | NA |

| Z. zhoukaiyae [24] | Dabie Mountain, Anhui Province, China | 2.31 ± 0.65 | 1.574 ± 0.023 | 10.7–13.7 | NA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hao, J.-J.; Chen, Z.-Q.; Hu, H.-L.; Cui, J.-G.; Ding, G.-H. Acoustic Diversity in Zhangixalus lishuiensis: Intra-Individual Variation, Acoustic Divergence, and Genus-Level Comparisons. Animals 2025, 15, 3493. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233493

Hao J-J, Chen Z-Q, Hu H-L, Cui J-G, Ding G-H. Acoustic Diversity in Zhangixalus lishuiensis: Intra-Individual Variation, Acoustic Divergence, and Genus-Level Comparisons. Animals. 2025; 15(23):3493. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233493

Chicago/Turabian StyleHao, Jia-Jun, Zhi-Qiang Chen, Hua-Li Hu, Jian-Guo Cui, and Guo-Hua Ding. 2025. "Acoustic Diversity in Zhangixalus lishuiensis: Intra-Individual Variation, Acoustic Divergence, and Genus-Level Comparisons" Animals 15, no. 23: 3493. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233493

APA StyleHao, J.-J., Chen, Z.-Q., Hu, H.-L., Cui, J.-G., & Ding, G.-H. (2025). Acoustic Diversity in Zhangixalus lishuiensis: Intra-Individual Variation, Acoustic Divergence, and Genus-Level Comparisons. Animals, 15(23), 3493. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233493