Characterization and Genomic Analysis of Pasteurella multocida NQ01 Isolated from Yak in China

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacteria Isolation and Culture Conditions

2.2. Identification and Genotyping

2.3. Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing

2.4. Median Lethal Dose Determination

2.5. Histopathological Analysis

2.6. Whole-Genome Sequencing and Genome Annotation of NQ01

2.7. Comparative Analysis of NQ01

3. Result

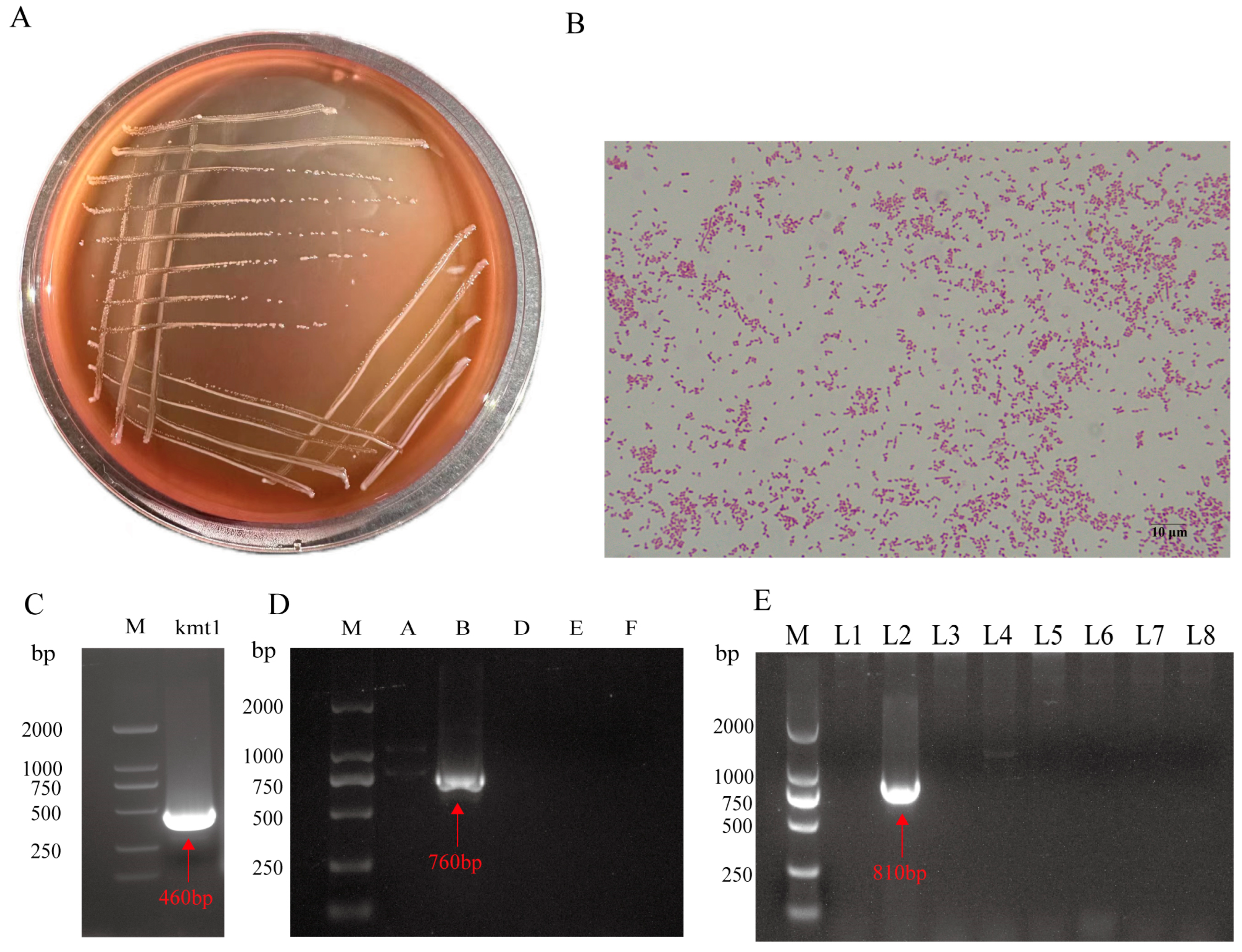

3.1. Isolation and Identification of NQ01

3.2. Antibiotic Susceptibility of NQ01

3.3. Evaluated Pathogenicity of NQ01

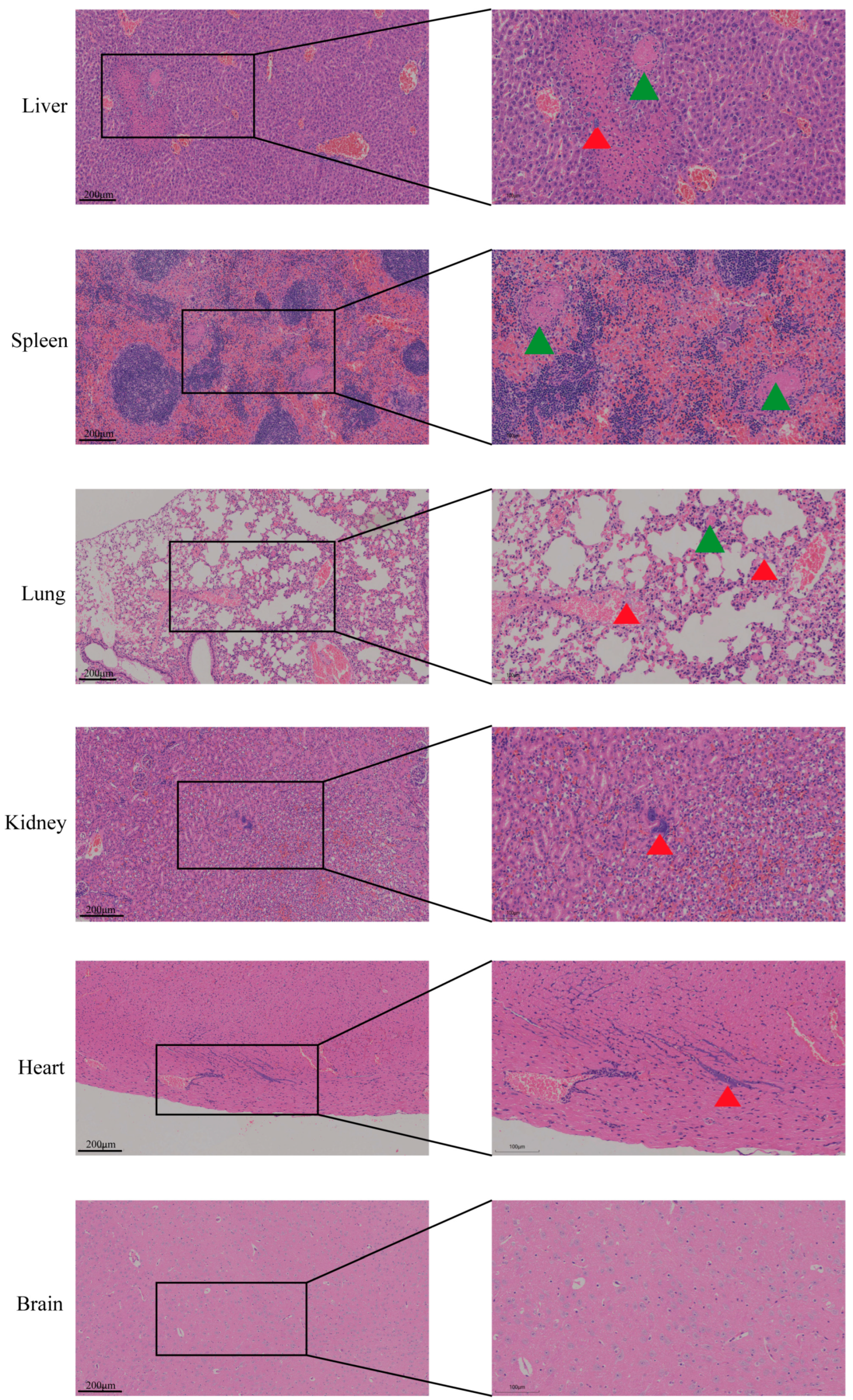

3.4. Pathological Changes Induced by NQ01 Infection

3.5. General Genomic Features of NQ01

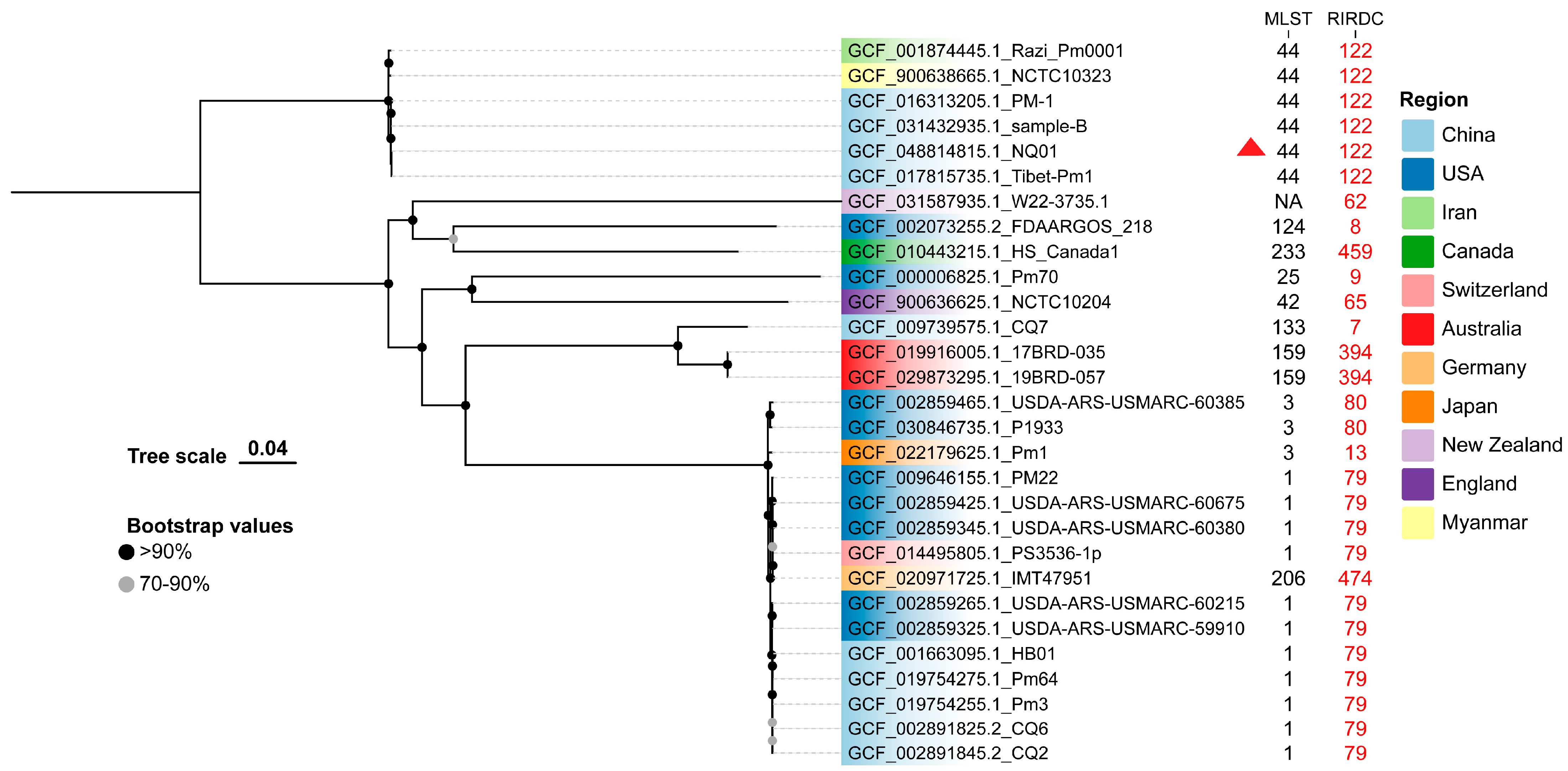

3.6. Comparative Analysis Between P. multocida Isolates from Bovine

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Carter, G.R. Studies on Pasteurella multocida. I. A hemagglutination test for the identification of serological types. Am. J. Vet. Res. 1955, 16, 481–484. [Google Scholar]

- Heddleston, K.L.; Gallagher, J.E.; Rebers, P.A. Fowl cholera: Gel diffusion precipitin test for serotyping Pasteruella multocida from avian species. Avian Dis. 1972, 16, 925–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, Y.H.; Moon, D.C.; Lee, Y.J.; Hyun, B.H.; Lim, S.K. Genetic and phenotypic characterization of tetracycline-resistant Pasteurella multocida isolated from pigs. Vet. Microbiol. 2019, 233, 159–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fegan, J.E.; Waeckerlin, R.C.; Tesfaw, L.; Islam, E.A.; Deresse, G.; Dufera, D.; Assefa, E.; Woldemedhin, W.; Legesse, A.; Akalu, M.; et al. Developing a PmSLP3-based vaccine formulation that provides robust long-lasting protection against hemorrhagic septicemia-causing serogroup B and E strains of Pasteurella multocida in cattle. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1392681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petruzzi, B.; Briggs, R.E.; Tatum, F.M.; Swords, W.E.; De Castro, C.; Molinaro, A.; Inzana, T.J. Capsular Polysaccharide Interferes with Biofilm Formation by Pasteurella multocida Serogroup A. mBio 2017, 8, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhao, Z.; Xi, X.; Xue, Q.; Long, T.; Xue, Y. Occurrence of Pasteurella multocida among pigs with respiratory disease in China between 2011 and 2015. Ir. Vet. J. 2017, 70, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Sun, S.; Chen, Y.; Chen, D.; Sang, L.; Xie, X. Pathogenic and genomic characterisation of a rabbit sourced Pasteurella multocida serogroup F isolate s4. BMC Vet. Res. 2022, 18, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrand, D.; Heeg, K.; Kubatzky, K.F. Pasteurella multocida toxin-stimulated osteoclast differentiation is B cell dependent. Infect. Immun. 2011, 79, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Kloos, B.; Roetz, N.; Schmidt, S.; Eigenbrod, T.; Kamitani, S.; Kubatzky, K.F. Influence of Pasteurella multocida Toxin on the differentiation of dendritic cells into osteoclasts. Immunobiology 2018, 223, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almoheer, R.; Abd Wahid, M.E.; Zakaria, H.A.; Jonet, M.A.B.; Al-Shaibani, M.M.; Al-Gheethi, A.; Addis, S.N.K. Spatial, Temporal, and Demographic Patterns in the Prevalence of Hemorrhagic Septicemia in 41 Countries in 2005–2019: A Systematic Analysis with Special Focus on the Potential Development of a New-Generation Vaccine. Vaccines 2022, 10, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lestari, T.D.; Khairullah, A.R.; Damayanti, R.; Mulyati, S.; Rimayanti, R.; Hernawati, T.; Utama, S.; Kusuma Wardhani, B.W.; Wibowo, S.; Ariani Kurniasih, D.A.; et al. Hemorrhagic septicemia: A major threat to livestock health. Open Vet. J. 2025, 15, 519–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindaraj, G.; Krishnamoorthy, P.; Nethrayini, K.R.; Shalini, R.; Rahman, H. Epidemiological features and financial loss due to clinically diagnosed Haemorrhagic Septicemia in bovines in Karnataka, India. Prev. Vet. Med. 2017, 144, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahboob, S.; Ullah, N.; Farhan Ul Haque, M.; Rauf, W.; Iqbal, M.; Ali, A.; Rahman, M. Genomic characterization and comparative genomic analysis of HS-associated Pasteurella multocida serotype B:2 strains from Pakistan. BMC Genom. 2023, 24, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddock, K.J.; Stenger, B.L.S.; Pecoraro, H.L.; Roberts, J.C.; Loy, J.D.; Webb, B.T. Hemorrhagic septicemia in the United States: Molecular characterization of isolates and comparison to a global collection. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 2025, 37, 771–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanda, M.M.; Purse, B.V.; Hemadri, D.; Patil, S.S.; Yogisharadhya, R.; Prajapati, A.; Shivachandra, S.B. Spatial and temporal analysis of haemorrhagic septicaemia outbreaks in India over three decades (1987–2016). Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 6773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mo, Q.; Nawaz, S.; Kulyar, M.F.; Li, K.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Rahim, M.F.; Ahmed, A.E.; Ijaz, F.; Li, J. Exploring the intricacies of Pasteurella multocida dynamics in high-altitude livestock and its consequences for bovine health: A personal exploration of the yak paradox. Microb. Pathog. 2024, 194, 106799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Q.; Zhang, G.; Ma, T.; Qian, W.; Wang, J.; Ye, Z.; Cao, C.; Hu, Q.; Kim, J.; Larkin, D.M.; et al. The yak genome and adaptation to life at high altitude. Nat. Genet. 2012, 44, 946–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, K.M.; Boyce, J.D.; Chung, J.Y.; Frost, A.J.; Adler, B. Genetic organization of Pasteurella multocida cap Loci and development of a multiplex capsular PCR typing system. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2001, 39, 924–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, M.; John, M.; Turni, C.; Edmunds, M.; St Michael, F.; Adler, B.; Blackall, P.J.; Cox, A.D.; Boyce, J.D. Development of a rapid multiplex PCR assay to genotype Pasteurella multocida strains by use of the lipopolysaccharide outer core biosynthesis locus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2015, 53, 477–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, H.; Wang, D.; Meng, F.; Yuan, Z.; Pan, C.; Zhao, C.; Shi, B.; Zeng, J. Prevalence and relative-risks of pasteurella in yaks of Xizang, China. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2025, 57, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patiño, P.; Gallego, C.; Martínez, N.; Rey, A.; Iregui, C. Intranasal instillation of Pasteurella multocida lipopolysaccharide in rabbits causes interstitial lung damage. Res. Vet. Sci. 2022, 152, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannaki, T.R.; Priyanka, E.; Haunshi, S. Research Note: Disease tolerance/resistance and host immune response to experimental infection with Pasteurella multocida A:1 isolate in Indian native Nicobari chicken breed. Poult. Sci. 2021, 100, 101268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becsei, Á.; Solymosi, N.; Csabai, I.; Magyar, D. Detection of antimicrobial resistance genes in urban air. Microbiologyopen 2021, 10, e1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porcheron, G.; Garénaux, A.; Proulx, J.; Sabri, M.; Dozois, C.M. Iron, copper, zinc, and manganese transport and regulation in pathogenic Enterobacteria: Correlations between strains, site of infection and the relative importance of the different metal transport systems for virulence. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2013, 3, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Pu, J.; Liu, Z.; Jiang, J.; Shang, D.; Dong, W. Metal ion-exchanged faujasite zeolites materials against clinically isolated multidrug-resistant bacteria. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2025, 41, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, M.; Boyce, J.D.; Adler, B. Pasteurella multocida pathogenesis: 125 years after Pasteur. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2006, 265, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacques, M.; Bélanger, M.; Diarra, M.S.; Dargis, M.; Malouin, F. Modulation of Pasteurella multocida capsular polysaccharide during growth under iron-restricted conditions and in vivo. Microbiology 1994, 140 Pt 2, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Qin, X.; Xu, N.; Li, P.; Wu, X.; Duan, L.; Du, Y.; Fang, R.; Hardwidge, P.R.; Li, N.; et al. Pasteurella multocida Pm0442 Affects Virulence Gene Expression and Targets TLR2 to Induce Inflammatory Responses. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosch, M.; Garrido, M.E.; Llagostera, M.; Pérez De Rozas, A.M.; Badiola, I.; Barbé, J. Characterization of the Pasteurella multocida hgbA gene encoding a hemoglobin-binding protein. Infect. Immun. 2002, 70, 5955–5964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhou, R.; Chen, H.; Wilson, B.A.; Wu, B. Pasteurella multocida: Genotypes and Genomics. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2019, 83, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, E.J.; Oh, E.K.; Lee, J.K. Role of HemF and HemN in the heme biosynthesis of Vibrio vulnificus under S-adenosylmethionine-limiting conditions. Mol. Microbiol. 2015, 96, 497–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, W.; Olczak, T.; Genco, C.A. Characterization and expression of HmuR, a TonB-dependent hemoglobin receptor of Porphyromonas gingivalis. J. Bacteriol. 2000, 182, 5737–5748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido, M.E.; Bosch, M.; Medina, R.; Llagostera, M.; Pérez de Rozas, A.M.; Badiola, I.; Barbé, J. The high-affinity zinc-uptake system znuACB is under control of the iron-uptake regulator (fur) gene in the animal pathogen Pasteurella multocida. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2003, 221, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tubulekas, I.; Hughes, D. Growth and translation elongation rate are sensitive to the concentration of EF-Tu. Mol. Microbiol. 1993, 8, 761–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, M.R.; Soni, V.; Brown, M.; Rosch, K.M.; Saleh, A.; Rhee, K.; Dörr, T. Sugar phosphate-mediated inhibition of peptidoglycan precursor synthesis. mBio 2025, 16, e0172925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroll, J.S.; Loynds, B.; Brophy, L.N.; Moxon, E.R. The bex locus in encapsulated Haemophilus influenzae: A chromosomal region involved in capsule polysaccharide export. Mol. Microbiol. 1990, 4, 1853–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, X.; Yuan, M.; Zheng, M.; Guo, Q.; Yang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Liang, X.; Liu, J.; Fang, C. Deletion of glycosyltransferase galE impairs the InlB anchoring and pathogenicity of Listeria monocytogenes. Virulence 2024, 15, 2422539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provost, M.; Harel, J.; Labrie, J.; Sirois, M.; Jacques, M. Identification, cloning and characterization of rfaE of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae serotype 1, a gene involved in lipopolysaccharide inner-core biosynthesis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2003, 223, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khonsari, S.; Cossu, A.; Vu, M.; Roulston, D.; Marvasi, M.; Purchase, D. Biosurfactant-Mediated Inhibition of Salmonella Typhimurium Biofilms on Plastics: Influence of Lipopolysaccharide Structure. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hummels, K.R. The regulation of lipid A biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2025, 301, 110556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yin, S.; Yi, D.; Zhang, H.; Li, Z.; Guo, F.; Chen, C.; Fang, W.; Wang, J. The Brucella melitensis M5-90ΔmanB live vaccine candidate is safer than M5-90 and confers protection against wild-type challenge in BALB/c mice. Microb. Pathog. 2017, 112, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Che, J.; Liu, B.; Fang, Q.; Hu, S.; Wang, L.; Bao, B. Role of msbB Gene in Physiology and Pathogenicity of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Post, D.M.; Ketterer, M.R.; Phillips, N.J.; Gibson, B.W.; Apicella, M.A. The msbB mutant of Neisseria meningitidis strain NMB has a defect in lipooligosaccharide assembly and transport to the outer membrane. Infect. Immun. 2003, 71, 647–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesur, M.F.; Siraj, B.; Uddin, R.; Durmuş, S.; Çakır, T. Network-Based Metabolism-Centered Screening of Potential Drug Targets in Klebsiella pneumoniae at Genome Scale. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2019, 9, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, K.; Liu, T.; Duan, B.; Liu, F.; Cao, M.; Peng, W.; Dai, Q.; Chen, H.; Yuan, F.; Bei, W. The CpxAR Two-Component System Contributes to Growth, Stress Resistance, and Virulence of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae by Upregulating wecA Transcription. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, S.; Gu, C.; Xiao, W.; Zhao, M.; Yu, Z.; He, L. Combined transcriptome and metabolome analysis reveals the regulatory network of histidine kinase QseC in the two-component system of Glaesserella parasuis. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1637383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolfaghar, I.; Evans, D.J.; Fleiszig, S.M. Twitching motility contributes to the role of pili in corneal infection caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect. Immun. 2003, 71, 5389–5393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrows, L.L. Pseudomonas aeruginosa twitching motility: Type IV pili in action. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2012, 66, 493–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xicohtencatl-Cortes, J.; Monteiro-Neto, V.; Ledesma, M.A.; Jordan, D.M.; Francetic, O.; Kaper, J.B.; Puente, J.L.; Girón, J.A. Intestinal adherence associated with type IV pili of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. J. Clin. Investig. 2007, 117, 3519–3529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna Rico, A.; Zheng, W.; Petiot, N.; Egelman, E.H.; Francetic, O. Functional reconstitution of the type IVa pilus assembly system from enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 2019, 111, 732–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberge, N.A.; Burrows, L.L. Building permits-control of type IV pilus assembly by PilB and its cofactors. J. Bacteriol. 2024, 206, e0035924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCallum, M.; Tammam, S.; Khan, A.; Burrows, L.L.; Howell, P.L. The molecular mechanism of the type IVa pilus motors. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohl, M.; Banks, E.J.; Manley, M.P.; Le, T.B.K.; Low, H.H. Bidirectional pilus processing in the Tad pilus system motor CpaF. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clock, S.A.; Planet, P.J.; Perez, B.A.; Figurski, D.H. Outer membrane components of the Tad (tight adherence) secreton of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans. J. Bacteriol. 2008, 190, 980–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, S.L.; Peretiazhko, I.; Karnani, S.Y.; Marmont, L.S.; Wheeler, J.H.R.; Tseng, B.S.; Durham, W.M.; Whitney, J.C.; Bergeron, J.R.C. The structure of the Tad pilus alignment complex reveals a periplasmic conduit for pilus extension. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 6977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasaki, H.; Ishikawa, H.; Terayama, H.; Asano, R.; Kawamoto, E.; Ishibashi, H.; Boot, R. Identification of a virulence determinant that is conserved in the Jawetz and Heyl biotypes of [Pasteurella] pneumotropica. Pathog. Dis. 2016, 74, ftw066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Description Tested Features | Gene | Primers | Sequences (5′-3′) | Product Size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. multocida | Kmt1 | F-kmt | ATCCGCTATTATCCAGTGG | 460 |

| R-kmt | GCTGTAAACGAACTCGCCA | |||

| Serogroup A | hyaD-hyaC | F-A | TGCCAAATCGCAGTCAG | 1044 |

| R-A | TTGCCATCATTGTCAGTG | |||

| Serogroup B | bcbD | F-B | CATTCTATCCAAGCTCCACC | 760 |

| R-B | GCCCGAGAGTTTCAATCC | |||

| Serogroup D | dcbF | F-D | TTACACTAAAGCTCCAGGAGCCC | 657 |

| R-D | CATCCACCACTCAACCATATCAG | |||

| Serogroup E | ecbJ | F-E | TCCGCAGAAATTATTGACTC | 511 |

| R-E | GCTTGCTGCTTGATTTTGTC | |||

| Serogroup F | fcbD | F-F | AATCGGAAACGCAGAAATCAG | 851 |

| R-F | TTCCGCCGTCAATTACTCG | |||

| LPS type 1 | pcgD- pcgB | F-1 | ACATTCGAGATAATACACCCG | 1307 |

| R-1 | ATTGGAGCACCCTAGTAACCC | |||

| LPS type 2 | nctA | F-2 | CTTAAAGTAACACTCGCTATTGC | 810 |

| R-2 | TTTGATTTCCCTTGGGATAGC | |||

| LPS type 3 | gatF | F-3 | TGCAGGCAGAGAGTTGATAAACCATC | 474 |

| R-3 | CAAAGATTGGTTCAAATCTGAATGGA | |||

| LPS type 4 | latB | F-4 | TTTCCATAGATTACCAATGCCG | 550 |

| R-4 | CTTCTAGTGGTAGTCTAATGTCGACC | |||

| LPS type 5 | rmlA rmlC | F-5 | AGATTGCATGGCAAATGGC | 1175 |

| R-5 | CAATCCTCGTAAGACCCCC | |||

| LPS type 6 | nctB | F-6 | TCTTTATAATTATACTCTCCCAAGG | 668 |

| R-6 | AATGAAGGTAAAAAGAGATAGCTGGAG | |||

| LPS type 7 | ppgB | F-7 | CCTAATTTATATCTCTCCCC | 931 |

| R-7 | CTAATATATAACCCACCAACGC | |||

| LPS type 8 | natG | F-8 | GAGAGTTACAAAAATGATCGGC | 225 |

| R-8 | TCCTGGTTCATATAGGTAGG |

| Temperature (°C) | Time |

|---|---|

| 94 | 5 min |

| 94 | 30 s for 35 cycles |

| 55 | 30 s for 35 cycles |

| 72 | 2 min for 35 cycles |

| 72 | 10 min |

| Category | Antibiotics | Concentration (per Piece) | Susceptibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| β-lactam | cefalexin | 30 μg | S |

| cefradine | 30 μg | S | |

| cefoperazone | 75 μg | S | |

| cefuroxime | 30 μg | S | |

| ceftazidime | 30 μg | S | |

| amoxicillin | 20 μg | S | |

| carbenicillin | 100 μg | S | |

| piperacillin | 100 μg | S | |

| aminoglycoside | neomycin | 30 μg | S |

| kanamycin | 30 μg | S | |

| gentamicin | 10 μg | S | |

| spectinomycin | 100 μg | S | |

| amikacin | 30 μg | S | |

| streptomycin | 10 μg | I | |

| tetracycline | doxycycline | 30 μg | S |

| minocycline | 30 μg | S | |

| quinolone | enrofloxacin | 10 μg | S |

| ciprofloxacin | 5 μg | S | |

| ofloxacin | 5 μg | I | |

| macrolide | medemycin | 30 μg | S |

| chloramphenicol | florfenicol | 30 μg | S |

| polypeptide | polymyxin | 300 IU | S |

| vancomycin | 30 μg | S | |

| nitroimidazole | metronidazole | 5 μg | R |

| sulfonamide | trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | 25 μg | R |

| lincosamide | clindamycin | 2 μg | R |

| Route of Administration | Dose (CFU/Mouse) | Survival | Survival Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 0 | 5/5 | 100% |

| Intraperitoneal injection | 1.9 | 5/5 | 100% |

| 3.8 | 2/5 | 40% | |

| 5.7 | 0/5 | 0 | |

| Intranasal instillation | 1.52 × 104 | 5/5 | 100% |

| 1.52 × 105 | 3/5 | 60% | |

| 1.52 × 106 | 0/5 | 0 |

| Category | Gene | Function | Terms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adherence | htpB | Hsp60 heat shock protein | 3 |

| tadA | TadA pilin | 1 | |

| rcpA | RcpA pilus assembly proteins | 1 | |

| PM_RS00430 | type II secretion system F family protein | 1 | |

| PM_RS00425 | GspE/PulE family protein | 1 | |

| pilB | GspE/PulE family protein | 1 | |

| ppdD | prepilin peptidase-dependent pilin | 1 | |

| tufA/tuf | elongation factor Tu | 6 | |

| PM_RS08640 | ComEA family DNA-binding protein | 1 | |

| Immune modulation | manB/yhxB | Phosphomannomutase | 4 |

| ABZJ_RS06285 | Capsular polysaccharides synthesize proteins | 1 | |

| ABD1_RS00310 | Capsular polysaccharides synthesize proteins | 1 | |

| bexD’ | Capsular polysaccharides synthesize proteins | 1 | |

| msbB | Lipid A biosynthesis acyltransferase | 4 | |

| pgi | Glucose-6-phosphate isomerase | 2 | |

| wecA | Undecaprenyl-phosphate alpha-N-acetylglucosaminyl 1-phosphate transferase | 1 | |

| kdsA | 2-dehydro-3-deoxyphosphooctonate aldolase | 6 | |

| rfaE | ADP-heptose synthetase | 2 | |

| galE | Udp-glucose 4-epimerase | 2 | |

| lpxC | UDP-3-O-acyl-N-acetylglucosamine deacetylase | 4 | |

| gmhA/lpcA | Phosphoheptose isomerase | 3 | |

| lpxB | Lipid-A-disaccharide synthase | 2 | |

| lpxD | UDP-3-O-(3-hydroxymyristoyl)glucosamine N-acyltransferase | 2 | |

| rfaF | ADP-heptose--LPS heptosyltransferase II | 4 | |

| Nutritional/metabolic factor | hgbA | Hemoglobin-binding protein A | 1 |

| hemR | Hemin receptor | 2 | |

| hemN | Oxygen-independent coproporphyrinogen III oxidase | 4 | |

| Effector delivery system | PM_RS08160 | YadA-like Protein | 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, K.; Yuan, H.; Jin, C.; Rahim, M.F.; Luosong, X.; An, T.; Li, J. Characterization and Genomic Analysis of Pasteurella multocida NQ01 Isolated from Yak in China. Animals 2025, 15, 3462. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233462

Li K, Yuan H, Jin C, Rahim MF, Luosong X, An T, Li J. Characterization and Genomic Analysis of Pasteurella multocida NQ01 Isolated from Yak in China. Animals. 2025; 15(23):3462. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233462

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Kewei, Haofang Yuan, Chao Jin, Muhammad Farhan Rahim, Xire Luosong, Tianwu An, and Jiakui Li. 2025. "Characterization and Genomic Analysis of Pasteurella multocida NQ01 Isolated from Yak in China" Animals 15, no. 23: 3462. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233462

APA StyleLi, K., Yuan, H., Jin, C., Rahim, M. F., Luosong, X., An, T., & Li, J. (2025). Characterization and Genomic Analysis of Pasteurella multocida NQ01 Isolated from Yak in China. Animals, 15(23), 3462. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233462