Complex Sound Discrimination in Zebrafish: Auditory Learning Within a Novel “Go/Go” Decision-Making Paradigm

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal Acquisition and Maintenance

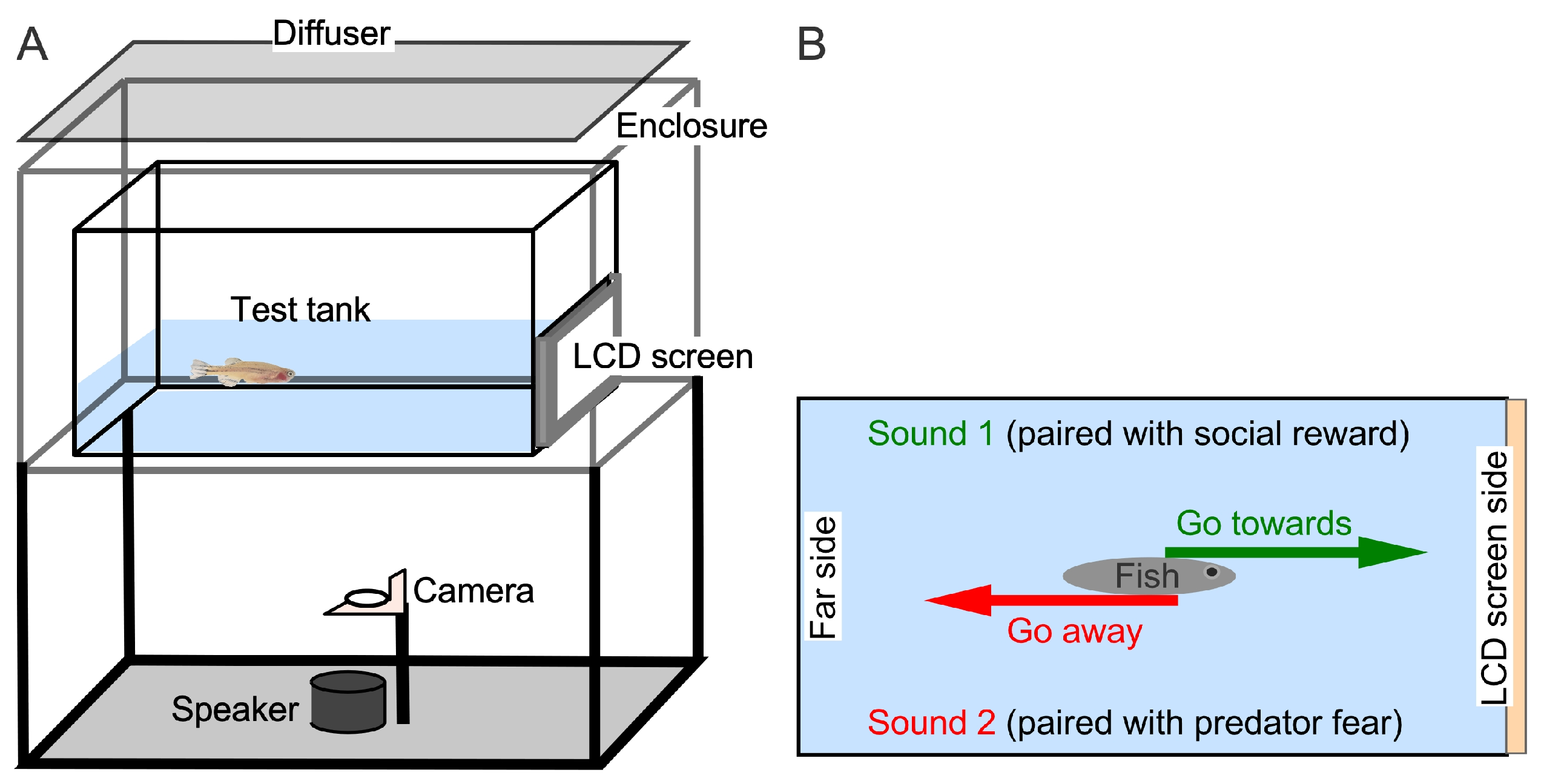

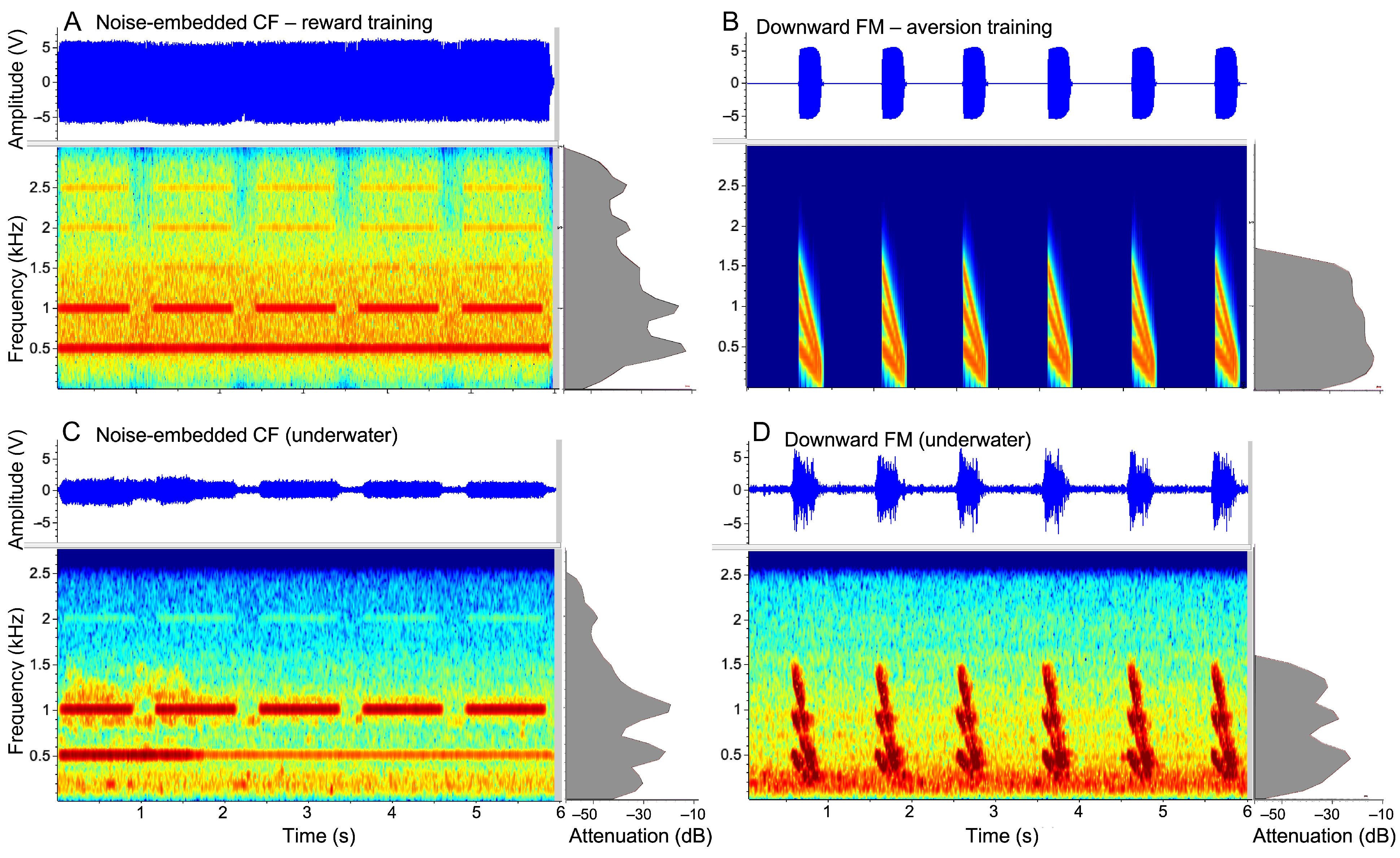

2.2. Experimental Setup and Control

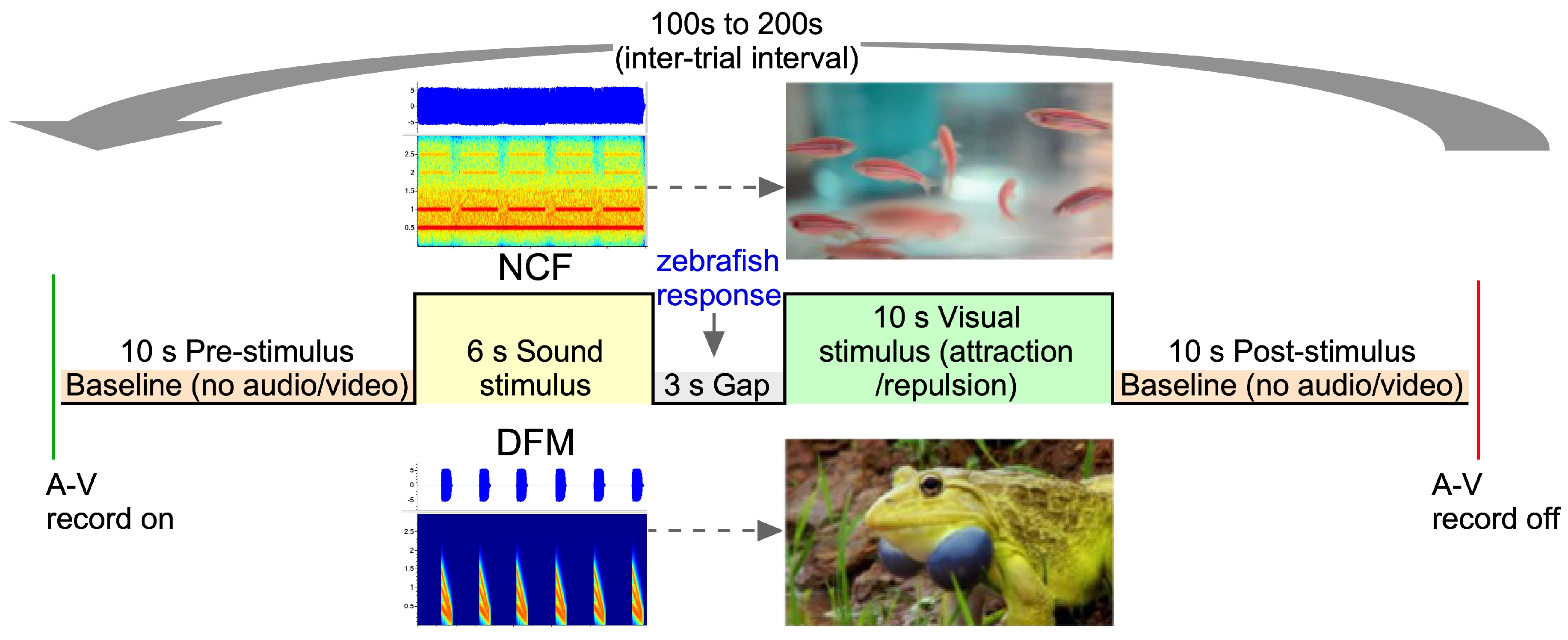

2.3. Experimental Paradigm and Control

2.4. Animal Tracking

2.5. Data Analysis and Statistical Methods

3. Results

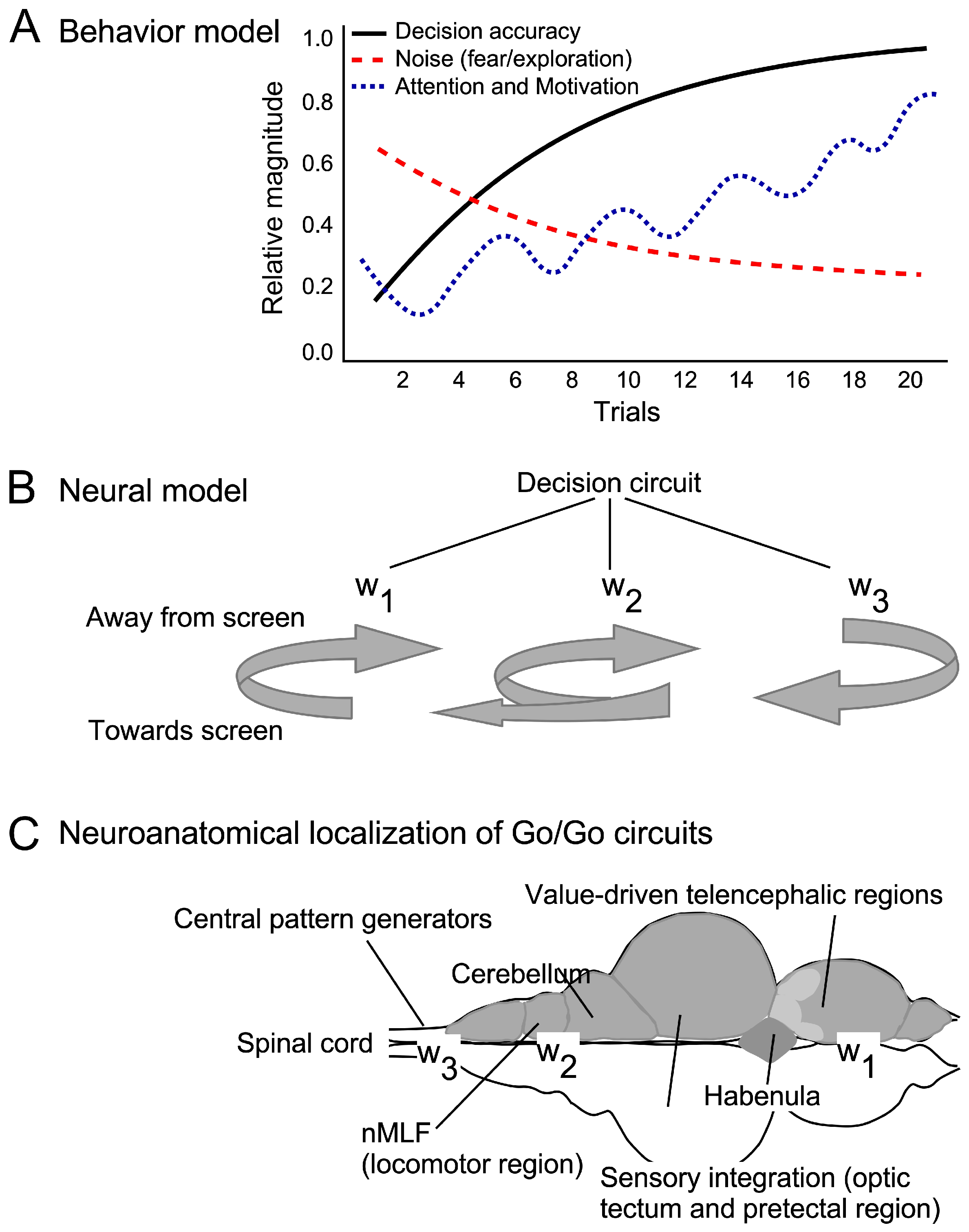

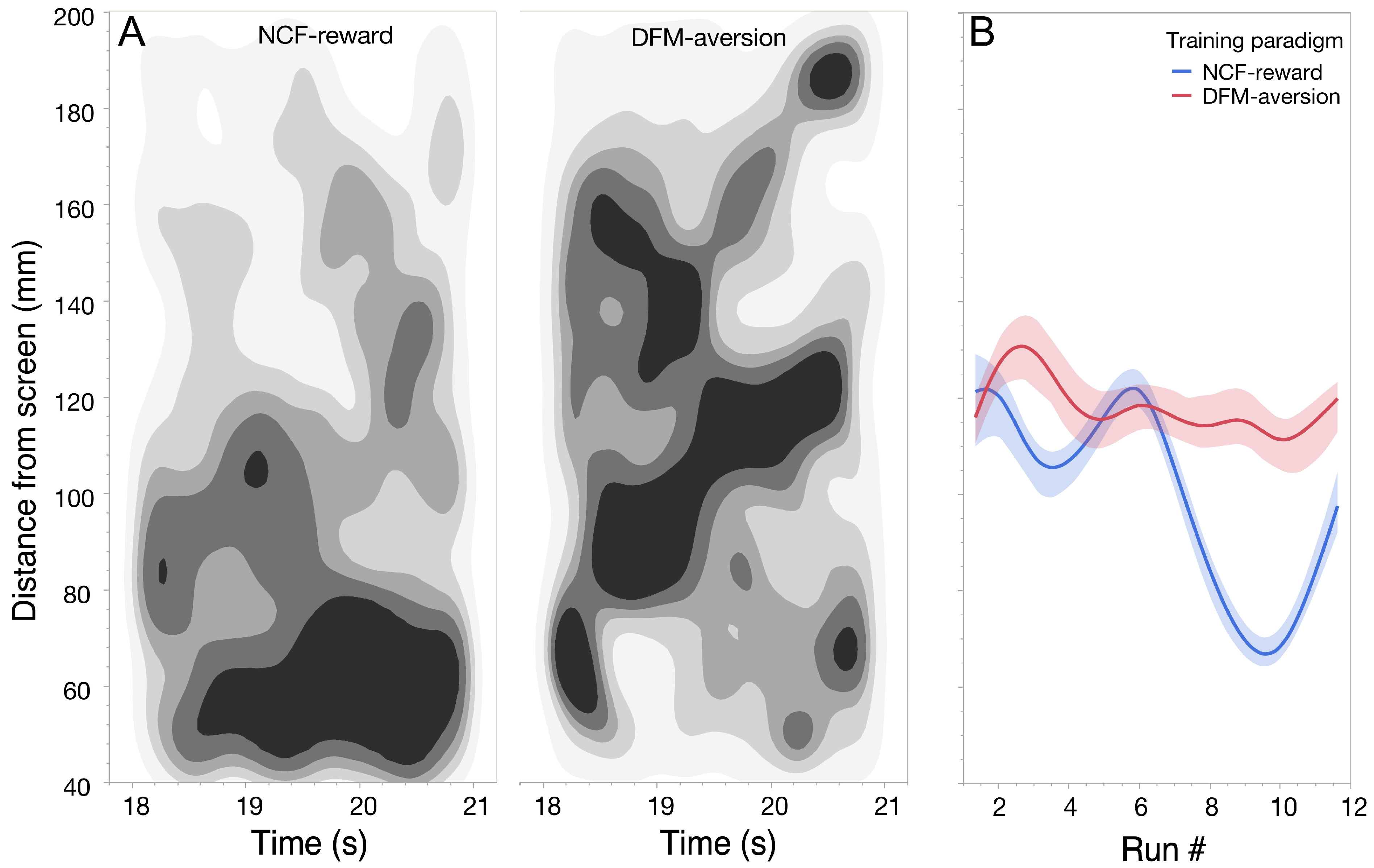

3.1. Learning Dynamics During Associative Conditioning

3.2. Post-Conditioning Swim Trajectories

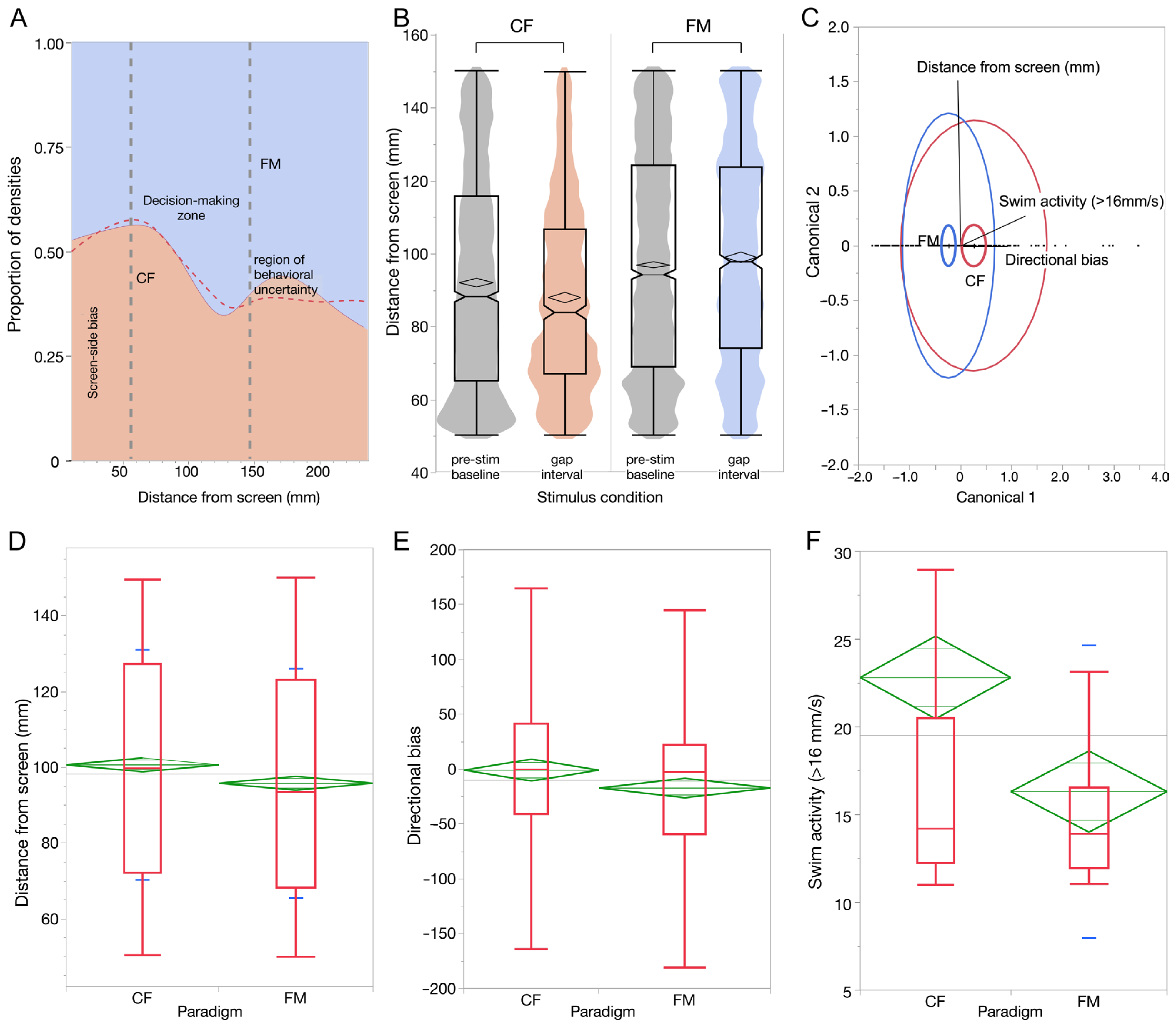

3.3. Behavioral Evedence for Complex Sound Discrimination

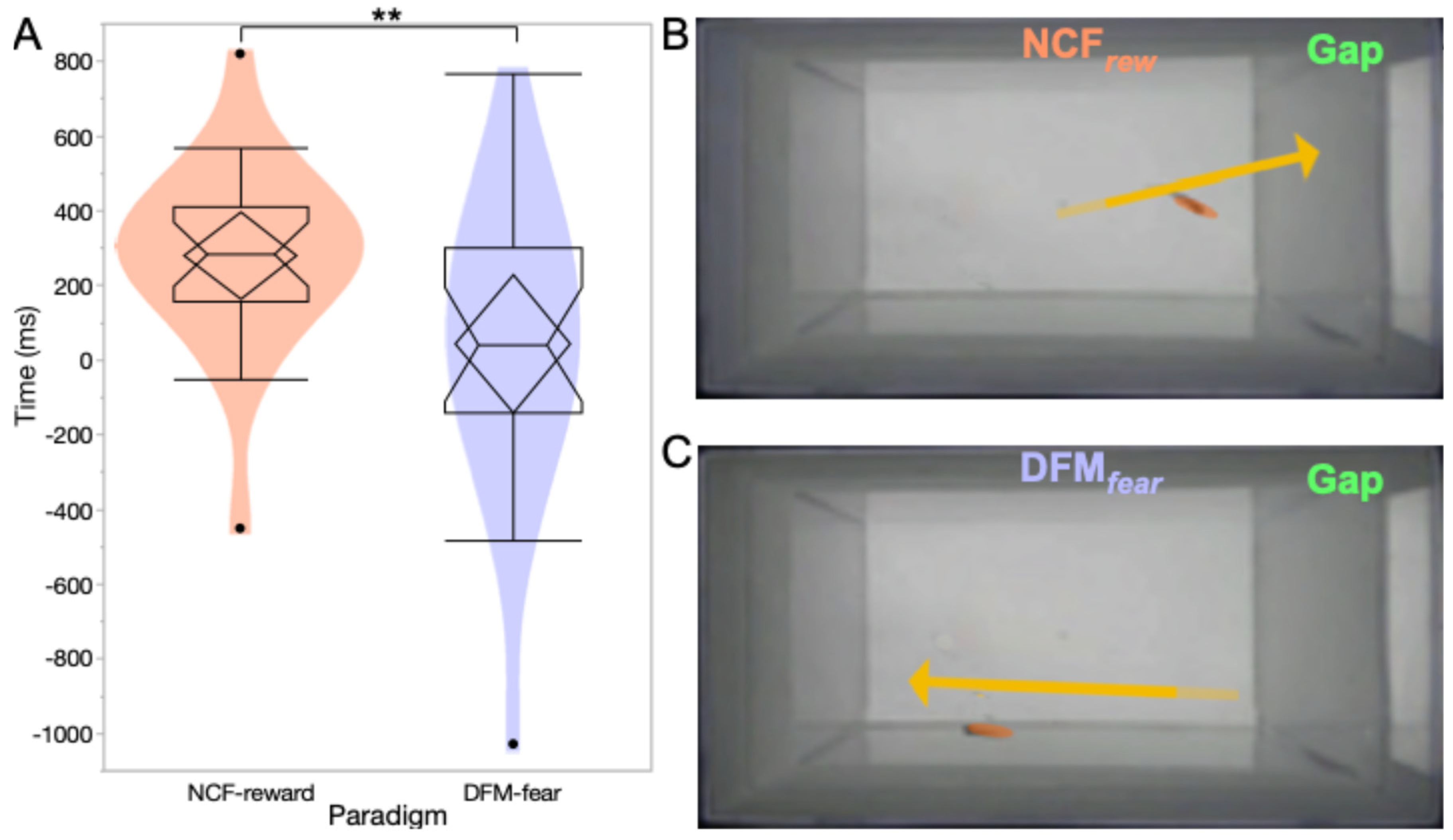

3.4. Overnight Memory Consolidation

4. Discussion

4.1. Sound in the Aquatic Environment

4.2. Hearing in Fishes

4.3. On-the-Go Learning

4.4. A State-Based Model for Auditory Learning

4.5. Neural Circuits Underlying Motivated Swimming and Decision-Making

4.6. Methodological Applications and Future Directions

5. Summary and Conclusions

6. Patents

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fay, R.R.; Popper, A.N. (Eds.) Comparative Hearing: Fish and Amphibians; Springer Handbook of Auditory Research; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1999; Volume 11, ISBN 978-1-4612-0533-3. [Google Scholar]

- Maruska, K.P.; Ung, U.S.; Fernald, R.D. The African cichlid fish Astatotilapia burtoni uses acoustic communication for reproduction: Sound production, hearing, and behavioral significance. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e37612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervi, A.L.; Poling, K.R.; Higgs, D.M. Behavioral measure of frequency detection and discrimination in the zebrafish, Danio rerio. Zebrafish 2012, 9, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popper, A.N.; Sisneros, J.A. The sound world of zebrafish: A critical review of hearing assessment. Zebrafish 2022, 19, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popper, A.N.; Hawkins, A.D. An overview of fish bioacoustics and the impacts of anthropogenic sounds on fishes. J. Fish Biol. 2019, 94, 692–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Te Velde, K.; Mairo, A.; Peeters, E.T.; Winter, H.V.; Tudorache, C.; Slabbekoorn, H. Natural soundscapes of lowland river habitats and the potential threat of urban noise pollution to migratory fish. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 359, 124517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Manna, G.; Manghi, M.; Perretti, F.; Sarà, G. Behavioral response of brown meagre (Sciaena umbra) to boat noise. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2016, 110, 324–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banse, M.; Hanssen, N.; Sabbe, J.; Lecchini, D.; Donaldson, T.J.; Iwankow, G.; Lagant, A.; Parmentier, E. Same calls, different meanings: Acoustic communication of Holocentridae. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0312191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhandiwad, A.A.; Sisneros, J.A. Revisiting psychoacoustic methods for the assessment of fish hearing. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2016, 877, 157–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulsen, R.E.; Scholz, L.A.; Constantin, L.; Favre-Bulle, I.; Vanwalleghem, G.C.; Scott, E.K. Broad frequency sensitivity and complex neural coding in the larval zebrafish auditory system. Curr. Biol. 2021, 31, 1977–1987.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holt, D.E.; Johnston, C.E. Can you hear the dinner bell? Response of cyprinid fishes to environmental acoustic cues. Anim. Behav. 2011, 82, 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fay, R.R. Spectral contrasts underlying auditory stream segregation in goldfish (Carassius auratus). J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 2000, 1, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretschneider, F.; van Veen, H.; Teunis, P.F.M.; Peters, R.C.; van den Berg, A.V. Zebrafish can hear sound pressure and particle motion in a synthesized sound field. Anim. Biol. 2013, 63, 199–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easa Murad, T.; Al-Aboosi, Y. Bit error performance enhancement for underwater acoustic noise channel by using channel coding. Jeasd 2023, 27, 659–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.-X.; Feng, A.S.; Xu, Z.-M.; Yu, Z.-L.; Arch, V.S.; Yu, X.-J.; Narins, P.M. Ultrasonic frogs show hyperacute phonotaxis to female courtship calls. Nature 2008, 453, 914–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehret, G. Comparative psychoacoustics: Perspectives of peripheral sound analysis in mammals. Naturwissenschaften 1977, 64, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marler, P. Bird calls: Their potential for behavioral neurobiology. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2004, 1016, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melcón, M.L.; Moss, C.F. How Nature Shaped Echolocation in Animals; Frontiers E-Books; Frontiers: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2014; ISBN 2889193470. [Google Scholar]

- Poirier, C.; Boumans, T.; Verhoye, M.; Balthazart, J.; Van der Linden, A. Own-song recognition in the songbird auditory pathway: Selectivity and lateralization. J. Neurosci. 2009, 29, 2252–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, A.S.; Narins, P.M.; Xu, C.-H.; Lin, W.-Y.; Yu, Z.-L.; Qiu, Q.; Xu, Z.-M.; Shen, J.-X. Ultrasonic communication in frogs. Nature 2006, 440, 333–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boumans, T.; Theunissen, F.E.; Poirier, C.; Van Der Linden, A. Neural representation of spectral and temporal features of song in the auditory forebrain of zebra finches as revealed by functional MRI. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2007, 26, 2613–2626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissler, D.B.; Ehret, G. Time-critical integration of formants for perception of communication calls in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 9021–9025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, C.F.; Surlykke, A. Auditory scene analysis by echolocation in bats. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2001, 110, 2207–2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwal, J.S.; Rauschecker, J.P. Auditory cortex of bats and primates: Managing species-specific calls for social communication. Front. Biosci. 2007, 12, 4621–4640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, C.; Nicol, T.; McGee, T.; Kraus, N. Thalamic asymmetry is related to acoustic signal complexity. Neurosci. Lett. 1999, 267, 89–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwal, J.S. Right-left asymmetry in the cortical processing of sounds for social communication vs. navigation in mustached bats. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2012, 35, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radford, C.A.; Montgomery, J.C. Potential competitive dynamics of acoustic ecology. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2016, 875, 895–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remage-Healey, L.; Nowacek, D.P.; Bass, A.H. Dolphin foraging sounds suppress calling and elevate stress hormone levels in a prey species, the Gulf toadfish. J. Exp. Biol. 2006, 209, 4444–4451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, A.H. A tale of two males: Behavioral and neural mechanisms of alternative reproductive tactics in midshipman fish. Horm. Behav. 2024, 161, 105507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim, M.C.P. The role of acoustic signals in fish reproduction. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2023, 154, 2959–2973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balebail, S.; Sisneros, J.A. Long duration advertisement calls of nesting male plainfin midshipman fish are honest indicators of size and condition. J. Exp. Biol. 2022, 225, jeb243889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groneberg, A.H.; Dressler, L.E.; Kadobianskyi, M.; Müller, J.; Judkewitz, B. Development of sound production in Danionella cerebrum. J. Exp. Biol. 2024, 227, jeb247782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, V.A.N.O.; Groneberg, A.H.; Hoffmann, M.; Kadobianskyi, M.; Veith, J.; Schulze, L.; Henninger, J.; Britz, R.; Judkewitz, B. Ultrafast sound production mechanism in one of the smallest vertebrates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2314017121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, R.S.; McVay, S. Songs of humpback whales. Science 1971, 173, 585–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janik, V.M.; Sayigh, L.S.; Wells, R.S. Signature whistle shape conveys identity information to bottlenose dolphins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 8293–8297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenney, J.W.; Steadman, P.E.; Young, O.; Shi, M.T.; Polanco, M.; Dubaishi, S.; Covert, K.; Mueller, T.; Frankland, P.W. A 3D adult zebrafish brain atlas (AZBA) for the digital age. eLife 2021, 10, e69988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renninger, S.L.; Orger, M.B. Two-photon imaging of neural population activity in zebrafish. Methods 2013, 62, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feierstein, C.E.; Portugues, R.; Orger, M.B. Seeing the whole picture: A comprehensive imaging approach to functional mapping of circuits in behaving zebrafish. Neuroscience 2015, 296, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panier, T.; Romano, S.A.; Olive, R.; Pietri, T.; Sumbre, G.; Candelier, R.; Debrégeas, G. Fast functional imaging of multiple brain regions in intact zebrafish larvae using selective plane illumination microscopy. Front. Neural Circuits 2013, 7, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, K.; Clark, M.D.; Torroja, C.F.; Torrance, J.; Berthelot, C.; Muffato, M.; Collins, J.E.; Humphray, S.; McLaren, K.; Matthews, L.; et al. The zebrafish reference genome sequence and its relationship to the human genome. Nature 2013, 496, 498–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henke, K.; Bowen, M.E.; Harris, M.P. Perspectives for identification of mutations in the zebrafish: Making use of next-generation sequencing technologies for forward genetic approaches. Methods 2013, 62, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunwald, D.J.; Eisen, J.S. Headwaters of the zebrafish—Emergence of a new model vertebrate. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2002, 3, 717–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalueff, A.V.; Echevarria, D.J.; Stewart, A.M. Gaining translational momentum: More zebrafish models for neuroscience research. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2014, 55, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, B.D.; Franscescon, F.; Rosemberg, D.B.; Norton, W.H.J.; Kalueff, A.V.; Parker, M.O. Zebrafish models for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2019, 100, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buckley, C.E.; Goldsmith, P.; Franklin, R.J.M. Zebrafish myelination: A transparent model for remyelination? Dis. Model. Mech. 2008, 1, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumbre, G.; de Polavieja, G.G. The world according to zebrafish: How neural circuits generate behavior. Front. Neural Circuits 2014, 8, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, W.; Bally-Cuif, L. Adult zebrafish as a model organism for behavioural genetics. BMC Neurosci. 2010, 11, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portugues, R.; Engert, F. The neural basis of visual behaviors in the larval zebrafish. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2009, 19, 644–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Darlington, T.R.; Lisberger, S.G. The neural basis for response latency in a sensory-motor behavior. Cereb. Cortex 2020, 30, 3055–3073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bollmann, J.H. The zebrafish visual system: From circuits to behavior. Annu. Rev. Vis. Sci. 2019, 5, 269–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, S.E.; Amburgey, K.; Horstick, E.; Linsley, J.; Sprague, S.M.; Cui, W.W.; Zhou, W.; Hirata, H.; Saint-Amant, L.; Hume, R.I.; et al. TRPM7 is required within zebrafish sensory neurons for the activation of touch-evoked escape behaviors. J. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 11633–11644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolson, T.; Rüsch, A.; Friedrich, R.W.; Granato, M.; Ruppersberg, J.P.; Nüsslein-Volhard, C. Genetic analysis of vertebrate sensory hair cell mechanosensation: The zebrafish circler mutants. Neuron 1998, 20, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcon, M.; Benvenutti, R.; Gallas-Lopes, M.; Herrmann, A.P.; Piato, A. What do male and female zebrafish prefer? Directional and colour preference in maze tasks. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2022, 56, 4546–4557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vendrell-Llopis, N.; Yaksi, E. Evolutionary conserved brainstem circuits encode category, concentration and mixtures of taste. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 17825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, S.M.; Vogt, R.G. Behavioral responses of newly hatched zebrafish (Danio rerio) to amino acid chemostimulants. Chem. Senses 2004, 29, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engeszer, R.E.; Patterson, L.B.; Rao, A.A.; Parichy, D.M. Zebrafish in the wild: A review of natural history and new notes from the field. Zebrafish 2007, 4, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parichy, D.M. Advancing biology through a deeper understanding of zebrafish ecology and evolution. eLife 2015, 4, e5635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohanty, N.P.; Measey, J. What’s for dinner? Diet and potential trophic impact of an invasive anuran Hoplobatrachus tigerinus on the Andaman archipelago. PeerJ 2018, 6, e5698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, A.M. Call recognition in the bullfrog, Rana catesbeiana: Generalization along the duration continuum. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2004, 115, 1345–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgs, D.M.; Souza, M.J.; Wilkins, H.R.; Presson, J.C.; Popper, A.N. Age- and size-related changes in the inner ear and hearing ability of the adult zebrafish (Danio rerio). J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 2002, 3, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.J.; Zu, L.; Summers, J.; Asdjodi, S.; Glasgow, E.; Kanwal, J.S. NemoTrainer: Automated conditioning for stimulus-directed navigation and decision making in free-swimming zebrafish. Animals 2022, 13, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwal, J.S.; Singh, B.J. Systems and Methods for Automated Control of Animal Training and Discrimination Learning. U.S. Patent 10,568,305, 25 February 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Vanwalleghem, G.; Heap, L.A.; Scott, E.K. A profile of auditory-responsive neurons in the larval zebrafish brain. J. Comp. Neurol. 2017, 525, 3031–3043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popper, A.N.; Hawkins, A.D.; Sand, O.; Sisneros, J.A. Examining the hearing abilities of fishes. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2019, 146, 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishkin, M.; Pribram, K.H. Analysis of the effects of frontal lesions in monkey. I. Variations of delayed alternation. J. Comp. Physiol. Psychol. 1955, 48, 492–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirat, O.; Sternberg, J.R.; Severi, K.E.; Wyart, C. ZebraZoom: An automated program for high-throughput behavioral analysis and categorization. Front. Neural Circuits 2013, 7, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, A.; Huang, K.-H.; Portugues, R.; Engert, F. Ontogeny of classical and operant learning behaviors in zebrafish. Learn. Mem. 2012, 19, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoki, R.; Tsuboi, T.; Okamoto, H. Y-maze avoidance: An automated and rapid associative learning paradigm in zebrafish. Neurosci. Res. 2015, 91, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudai, Y. The restless engram: Consolidations never end. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2012, 35, 227–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, P.H.; Cox, M. Underwater sound as a biological stimulus. In Sensory Biology of Aquatic Animals; Atema, J., Fay, R.R., Popper, A.N., Tavolga, W.N., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1988; pp. 131–149. ISBN 978-1-4612-3714-3. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, A.D.; Popper, A.N. A sound approach to assessing the impact of underwater noise on marine fishes and invertebrates. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2016, 74, fsw205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, A.H.; Gilland, E.H.; Baker, R. Evolutionary origins for social vocalization in a vertebrate hindbrain-spinal compartment. Science 2008, 321, 417–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tatarsky, R.L.; Guo, Z.; Campbell, S.C.; Kim, H.; Fang, W.; Perelmuter, J.T.; Schuppe, E.R.; Reeve, H.K.; Bass, A.H. Acoustic and postural displays in a miniature and transparent teleost fish, Danionella dracula. J. Exp. Biol. 2022, 225, jeb244585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Xu, J.; Chang, S.; Keniston, L.; Yu, L. Multisensory-guided associative learning enhances multisensory representation inprimary auditory cortex. Cereb. Cortex 2022, 32, 1040–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.; Xu, J.; Zheng, M.; Keniston, L.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, J.; Yu, L. Integrating visual information into the auditory cortex promotes sound discrimination through choice-related multisensory integration. J. Neurosci. 2022, 42, 8556–8568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandiwad, A.A.; Zeddies, D.G.; Raible, D.W.; Rubel, E.W.; Sisneros, J.A. Auditory sensitivity of larval zebrafish (Danio rerio) measured using a behavioral prepulse inhibition assay. J. Exp. Biol. 2013, 216, 3504–3513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgs, D.M.; Radford, C.A. The contribution of the lateral line to “hearing” in fish. J. Exp. Biol. 2013, 216, 1484–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindseth, A.; Lobel, P. Underwater soundscape monitoring and fish bioacoustics: A review. Fishes 2018, 3, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, L.; Rice, A.N. Vibrational and acoustic communication in fishes: The overlooked overlap between the underwater vibroscape and soundscape. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2023, 154, 2708–2720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeddies, D.G.; Fay, R.R. Development of the acoustically evoked behavioral response in zebrafish to pure tones. J. Exp. Biol. 2005, 208, 1363–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von der Emde, G.; Fetz, S. Distance, shape and more: Recognition of object features during active electrolocation in a weakly electric fish. J. Exp. Biol. 2007, 210, 3082–3095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wert, J.C.; Mensinger, A.F. Seasonal and Daily Patterns of the Mating Calls of the Oyster Toadfish, Opsanus tau. Biol. Bull. 2019, 236, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine, M.L.; Parmentier, E. Mechanisms of fish sound production. In Sound Communication in Fishes; Ladich, F., Ed.; Animal signals and communication; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 2015; Volume 4, pp. 77–126. ISBN 978-3-7091-1845-0. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, D.K.; Bhat, A. Alone but not always lonely: Social cues alleviate isolation induced behavioural stress in wild zebrafish. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2022, 251, 105623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Privat, M.; Romano, S.A.; Pietri, T.; Jouary, A.; Boulanger-Weill, J.; Elbaz, N.; Duchemin, A.; Soares, D.; Sumbre, G. Sensorimotor transformations in the zebrafish auditory system. Curr. Biol. 2019, 29, 4010–4023.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fattore, L.; Fadda, P.; Zanda, M.T.; Fratta, W. Analysis of opioid-seeking reinstatement in the rat. Methods Mol. Biol. 2015, 1230, 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghani, S.; Karia, M.; Cheng, R.-K.; Mathuru, A.S. An automated assay system to study novel tank induced anxiety. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Ferrero, F.; Bergomi, M.G.; Hinz, R.C.; Heras, F.J.H.; De Polavieja, G.G. Idtracker.ai: Tracking all individuals in small or large collectives of unmarked animals. Nat. Methods 2019, 16, 179–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolini, T.; Mwaffo, V.; Showler, A.; Macrì, S.; Butail, S.; Porfiri, M. Zebrafish response to 3D printed shoals of conspecifics: The effect of body size. Bioinspir. Biomim. 2016, 11, 026003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velkey, A.J.; Boles, J.; Betts, T.K.; Kay, H.; Henenlotter, R.; Wiens, K.M. High fidelity: Assessing zebrafish (Danio rerio) responses to social stimuli across several levels of realism. Behav. Processes 2019, 164, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butail, S.; Polverino, G.; Phamduy, P.; Del Sette, F.; Porfiri, M. Influence of robotic shoal size, configuration, and activity on zebrafish behavior in a free-swimming environment. Behav. Brain Res. 2014, 275, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Imari, L.; Gerlai, R. Sight of conspecifics as reward in associative learning in zebrafish (Danio rerio). Behav. Brain Res. 2008, 189, 216–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, M.; Wong, A.; Seguin, D.; Gerlai, R. Induction of social behavior in zebrafish: Live versus computer animated fish as stimuli. Zebrafish 2014, 11, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagnussat, N.; Piato, A.L.; Schaefer, I.C.; Blank, M.; Tamborski, A.R.; Guerim, L.D.; Bonan, C.D.; Vianna, M.R.M.; Lara, D.R. One for all and all for one: The importance of shoaling on behavioral and stress responses in zebrafish. Zebrafish 2013, 10, 338–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Nocera, D.; Finzi, A.; Rossi, S.; Staffa, M. The role of intrinsic motivations in attention allocation and shifting. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, N.A.; Bak, J.H.; International Brain Laboratory; Akrami, A.; Brody, C.D.; Pillow, J.W. Extracting the dynamics of behavior in sensory decision-making experiments. Neuron 2021, 109, 597–610.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoltowski, D.M.; Pillow, J.W.; Linderman, S.W. A general recurrent state space framework for modeling neural dynamics during decision-making. In Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Machine Learning, Online, 13–18 July 2020; PMLR: Westminster, UK, 2020; p. 119. [Google Scholar]

- He, M.; Das, P.; Hotan, G.; Purdon, P.L. Switching state-space modeling of neural signal dynamics. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2023, 19, e1011395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garst-Orozco, J.; Babadi, B.; Ölveczky, B.P. A neural circuit mechanism for regulating vocal variability during song learning in zebra finches. eLife 2014, 3, e03697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.C. State space modeling for analysis of behavior in learning experiments. In Advanced State Space Methods for Neural and Clinical Data; Chen, Z., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015; pp. 231–254. ISBN 9781139941433. [Google Scholar]

- Rusu, S.I.; Pennartz, C.M.A. Learning, memory and consolidation mechanisms for behavioral control in hierarchically organized cortico-basal ganglia systems. Hippocampus 2020, 30, 73–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brudner, S.; Pearson, J.; Mooney, R. Generative models of birdsong learning link circadian fluctuations in song variability to changes in performance. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2023, 19, e1011051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alrawashdeh, C.; Kanwal, J.S. Attention and Motivation Drive Learning: A Neural Model and Simulation of Auditory Attention-Driven Associative Leaning in Zebrafish, Danio rerio; NIH Brain Initiative: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bahl, A.; Engert, F. Neural circuits for evidence accumulation and decision making in larval zebrafish. Nat. Neurosci. 2020, 23, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ménard, A.; Grillner, S. Diencephalic locomotor region in the lamprey--afferents and efferent control. J. Neurophysiol. 2008, 100, 1343–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, P.; Tanabe, H.; Suster, M.L.; Ailani, D.; Kotani, Y.; Muto, A.; Itoh, M.; Iwasaki, M.; Wada, H.; Yaksi, E.; et al. Identification of a neuronal population in the telencephalon essential for fear conditioning in zebrafish. BMC Biol. 2018, 16, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baier, H.; Scott, E.K. Genetic and optical targeting of neural circuits and behavior—Zebrafish in the spotlight. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2009, 19, 553–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, P.M.; Jhou, T.; Li, B.; Matsumoto, M.; Mizumori, S.J.Y.; Stephenson-Jones, M.; Vicentic, A. The lateral habenula circuitry: Reward processing and cognitive control. J. Neurosci. 2016, 36, 11482–11488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groos, D.; Helmchen, F. The lateral habenula: A hub for value-guided behavior. Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 113968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agetsuma, M.; Aizawa, H.; Aoki, T.; Nakayama, R. The habenula is crucial for experience-dependent modification of fear responses in zebrafish. Nat. Neurosci. 2010, 13, 1354–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gahtan, E.; Tanger, P.; Baier, H. Visual prey capture in larval zebrafish is controlled by identified reticulospinal neurons downstream of the tectum. J. Neurosci. 2005, 25, 9294–9303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grätsch, S.; Auclair, F.; Demers, O.; Auguste, E.; Hanna, A.; Büschges, A.; Dubuc, R. A brainstem neural substrate for stopping locomotion. J. Neurosci. 2019, 39, 1044–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Chiang, A.-S.; Xia, S.; Kitamoto, T.; Tully, T.; Zhong, Y. Blockade of neurotransmission in Drosophila mushroom bodies impairs odor attraction, but not repulsion. Curr. Biol. 2003, 13, 1900–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Wei, J.; Rizak, J.D.; Chen, Y.; Wang, J.; Hu, X.; Ma, Y. An odor detection system based on automatically trained mice by relative go no-go olfactory operant conditioning. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 10019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathis, A.; Mamidanna, P.; Cury, K.M.; Abe, T.; Murthy, V.N.; Mathis, M.W.; Bethge, M. DeepLabCut: Markerless pose estimation of user-defined body parts with deep learning. Nat. Neurosci. 2018, 21, 1281–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashwood, Z.C.; Roy, N.A.; Stone, I.R.; International Brain Laboratory; Urai, A.E.; Churchland, A.K.; Pouget, A.; Pillow, J.W. Mice alternate between discrete strategies during perceptual decision-making. Nat. Neurosci. 2022, 25, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kähne, T.; Kolodziej, A.; Smalla, K.-H.; Eisenschmidt, E.; Haus, U.-U.; Weismantel, R.; Kropf, S.; Wetzel, W.; Ohl, F.W.; Tischmeyer, W.; et al. Synaptic proteome changes in mouse brain regions upon auditory discrimination learning. Proteomics 2012, 12, 2433–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, C.; Oikonomou, G.; Prober, D.A. Norepinephrine is required to promote wakefulness and for hypocretin-induced arousal in zebrafish. eLife 2015, 4, e07000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fosque, B.F.; Sun, Y.; Dana, H.; Yang, C.-T.; Ohyama, T.; Tadross, M.R.; Patel, R.; Zlatic, M.; Kim, D.S.; Ahrens, M.B.; et al. Neural circuits. Labeling of active neural circuits in vivo with designed calcium integrators. Science 2015, 347, 755–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moeyaert, B.; Holt, G.; Madangopal, R.; Perez-Alvarez, A.; Fearey, B.C.; Trojanowski, N.F.; Ledderose, J.; Zolnik, T.A.; Das, A.; Patel, D.; et al. Improved methods for marking active neuron populations. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curado, S.; Stainier, D.Y.R.; Anderson, R.M. Nitroreductase-mediated cell/tissue ablation in zebrafish: A spatially and temporally controlled ablation method with applications in developmental and regeneration studies. Nat. Protoc. 2008, 3, 948–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, M. Schooling fish from a new, multimodal sensory perspective. Animals 2024, 14, 1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Count | Paradigm | Distance from Screen (mm) | Swim Activity (>16 mm/s) | Directional Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 102 | CF | 98.579 | 17.487 | 61.316 |

| 118 | FM | 100.758 | 13.500 | −48.870 |

| 220 | All | 99.748 | 15.349 | 2.216 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Patel, A.; Mattapalli, S.; Kanwal, J.S. Complex Sound Discrimination in Zebrafish: Auditory Learning Within a Novel “Go/Go” Decision-Making Paradigm. Animals 2025, 15, 3452. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233452

Patel A, Mattapalli S, Kanwal JS. Complex Sound Discrimination in Zebrafish: Auditory Learning Within a Novel “Go/Go” Decision-Making Paradigm. Animals. 2025; 15(23):3452. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233452

Chicago/Turabian StylePatel, Anna, Sai Mattapalli, and Jagmeet S. Kanwal. 2025. "Complex Sound Discrimination in Zebrafish: Auditory Learning Within a Novel “Go/Go” Decision-Making Paradigm" Animals 15, no. 23: 3452. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233452

APA StylePatel, A., Mattapalli, S., & Kanwal, J. S. (2025). Complex Sound Discrimination in Zebrafish: Auditory Learning Within a Novel “Go/Go” Decision-Making Paradigm. Animals, 15(23), 3452. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233452