Molecular Monitoring of Leiocassis longirostris Using Species-Specific qPCR Assays from Environmental DNA

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling and Genomic DNA (gDNA) Extraction of Fish Specimens

2.2. DNA Sequencing

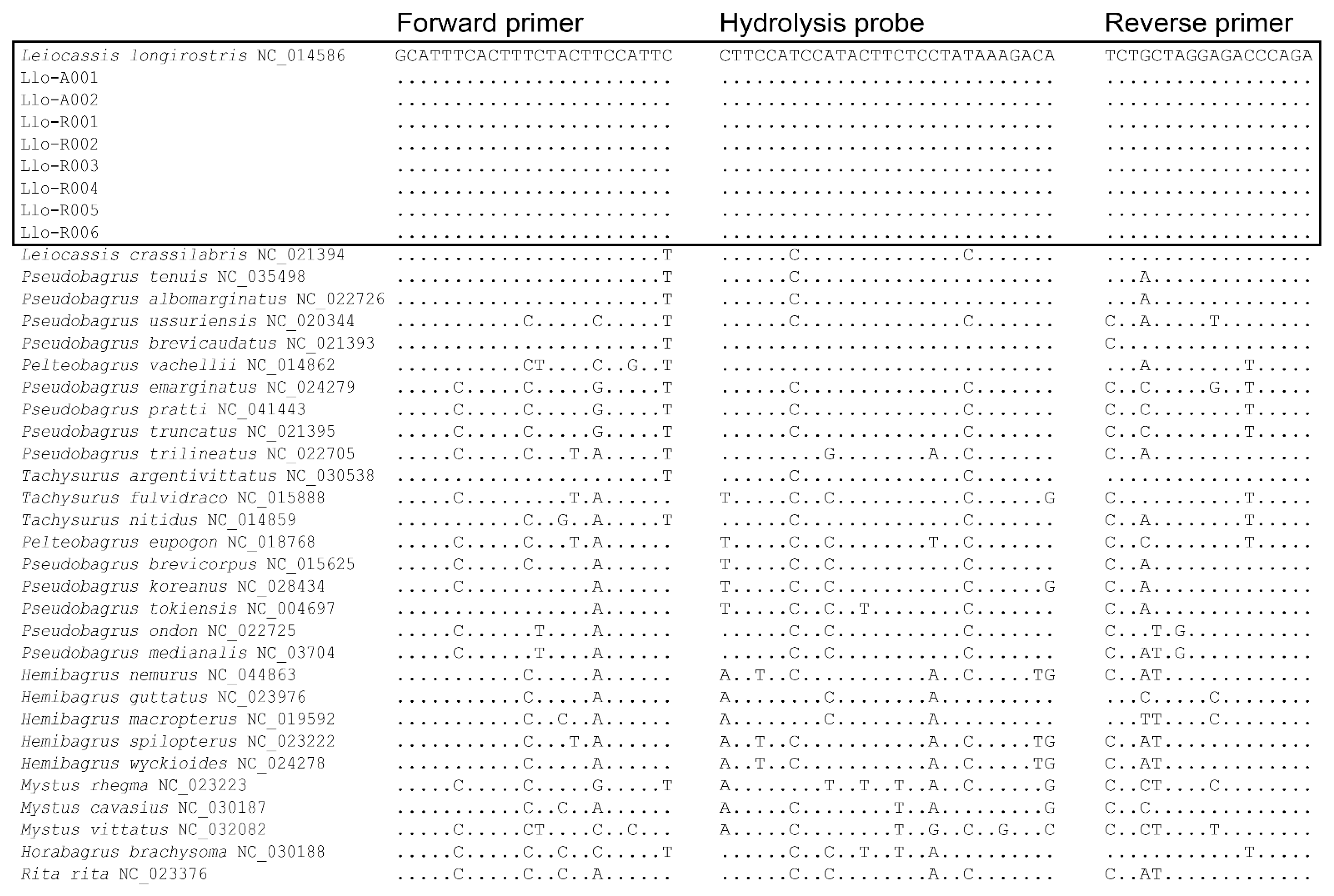

2.3. Design of Primers and Probe

2.4. Water and Sediment Sampling and eDNA Extraction

2.5. qPCR Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sequencing and Design of Primers and Probe

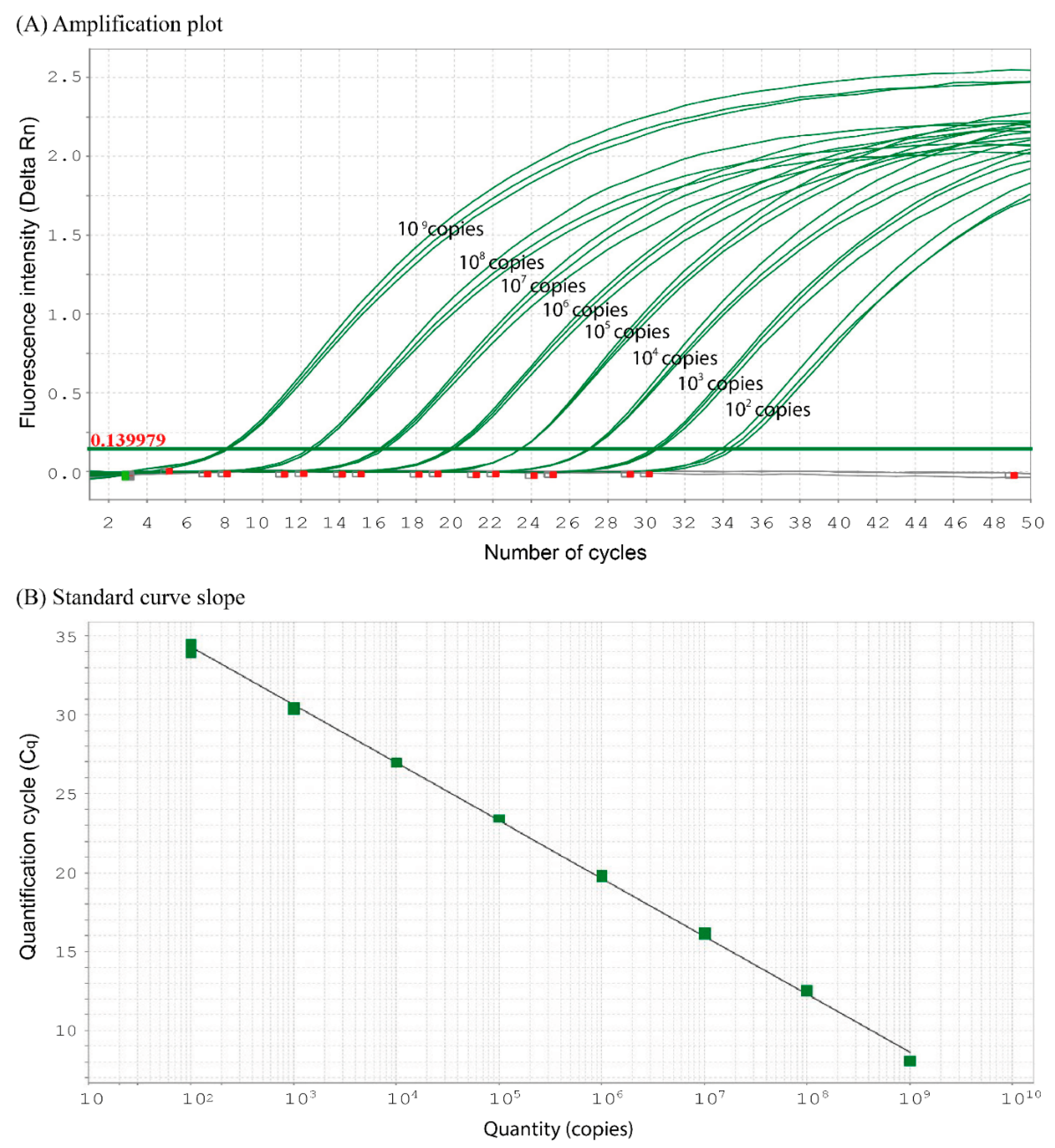

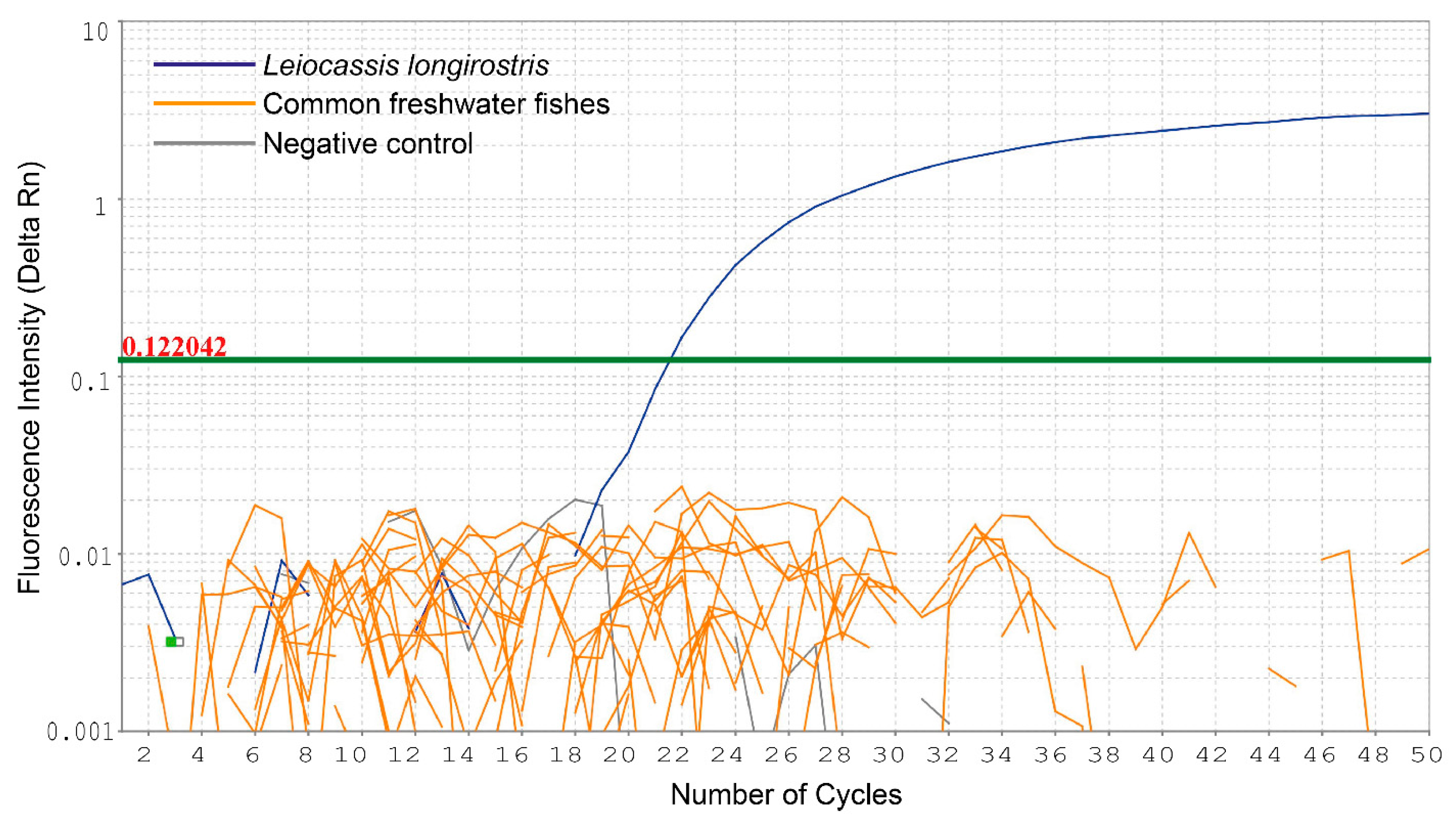

3.2. Sensitivity and Specificity Tests

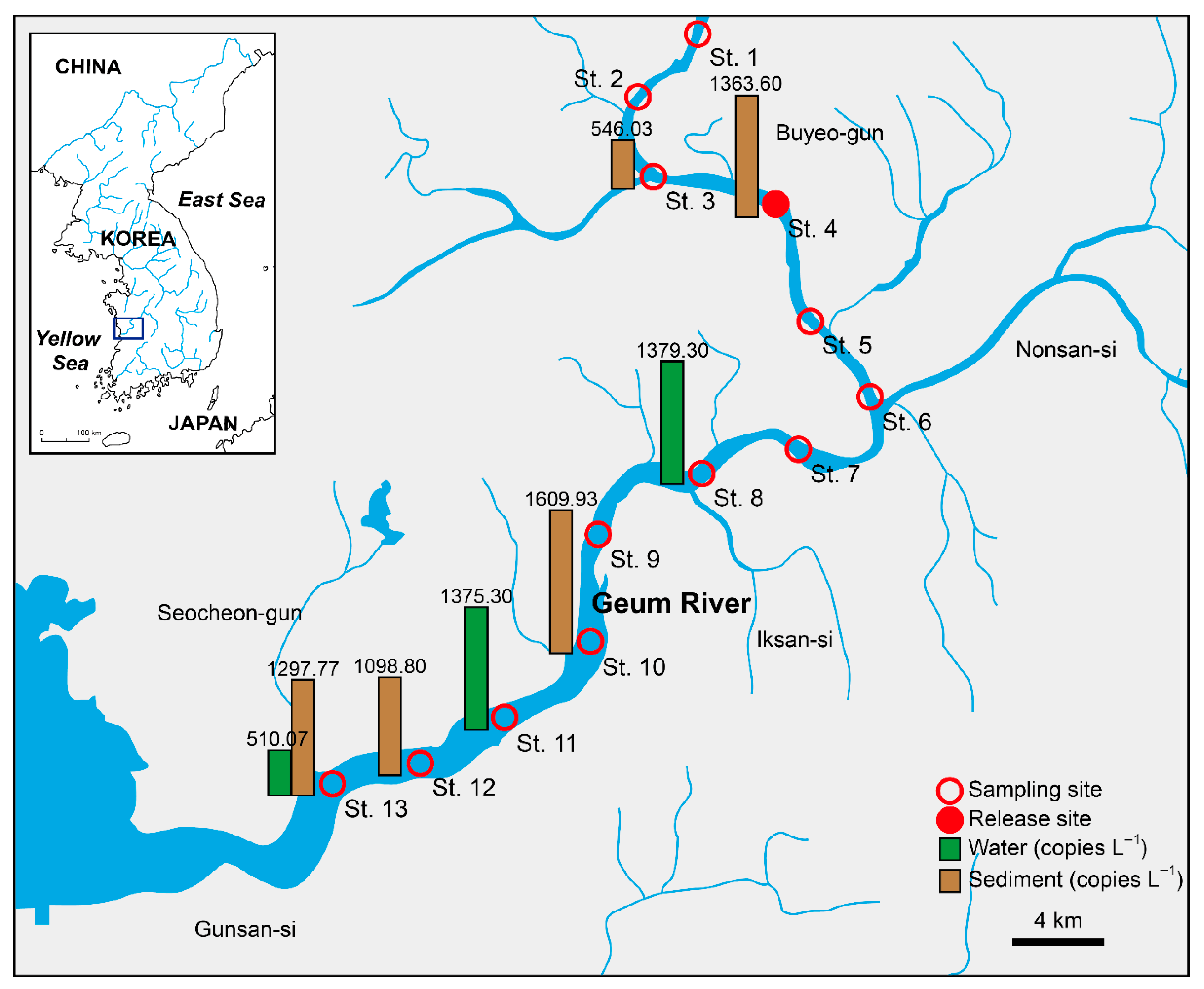

3.3. qPCR Assay of Environmental Samples

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kim, I.S.; Choi, Y.; Lee, C.L.; Lee, Y.J.; Kim, B.J.; Kim, J.H. Illustrated Book of Korean Fishes; Kyo-Hak Publishing: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2005. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Duan, Y.; Wu, W.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Mou, C.; Zhao, Z.; Zhao, H.; Du, J.; Zhou, J.; Li, Q. Research on longsnout catfish (Leiocassis longirostris) worldwide: Current status and future prospects. Rev. Aquacult. 2025, 17, e70092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIBR (National Institute of Biological Resources). Korean Red List of Threatened Species, 2nd ed.; Ministry of the Environment: Incheon, Republic of Korea, 2014; 246p. [Google Scholar]

- Bonar, S.A.; Hubert, W.A.; Willis, D.W. Standard Methods for Sampling North American Freshwater Fishes; American Fisheries Society: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2009; 335p. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.M.; Wells, S.P.; Mather, M.E.; Muth, R.M. Fish biodiversity sampling in stream ecosystems: A process for evaluating the appropriate types and amount of gear. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2014, 24, 338–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laramie, M.B.; Pilliod, D.S.; Goldberg, C.S. Characterizing the distribution of an endangered salmonid using environmental DNA analysis. Biol. Conserv. 2015, 183, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legge, S.; Robinson, N.; Lindenmayer, D.; Scheele, B.; Southwell, D.; Wintle, B. Monitoring Threatened Species and Ecological Communities; CSIRO Publishing: Melbourne, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ficetola, G.F.; Miaud, C.; Pompanon, F.; Taberlet, P. Species detection using environmental DNA from water samples. Biol. Lett. 2008, 4, 423–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, P.F.; Kielgast, J.O.; Iversen, L.L.; Wiuf, C.; Rasmussen, M.; Gilbert, M.T.P.; Orlando, L.; Willerslev, E. Monitoring endangered freshwater biodiversity using environmental DNA. Mol. Ecol. 2012, 21, 2565–2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, P.F.; Willerslev, E. Environmental DNA—An emerging tool in conservation for monitoring past and present biodiversity. Biol. Conserv. 2015, 183, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, M.A.; Turner, C.R. The ecology of environmental DNA and implications for conservation genetics. Conserv. Genet. 2016, 17, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beng, K.C.; Corlett, R.T. Applications of environmental DNA (eDNA) in ecology and conservation: Opportunities, challenges and prospects. Biodivers. Conserv. 2020, 29, 2089–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcox, T.M.; McKelvey, K.S.; Young, M.K.; Jane, S.F.; Lowe, W.H.; Whiteley, A.R.; Schwartz, M.K. Robust detection of rare species using environmental DNA: The importance of primer specificity. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e59520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.H.; Lee, S.I.; Lee, S.H.; Jo, S.E.; Kim, K.Y. The molecular monitoring of an invasive freshwater fish, brown trout (Salmo trutta), using real-time PCR assay and environmental water samples. Animals 2025, 15, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, C.; Faiq, M.E.; Li, Z.; Chen, G. Persistence and degradation dynamics of eDNA affected by environmental factors in aquatic ecosystems. Hydrobiologia 2022, 849, 4119–4133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, M.C.; Fraser, D.J.; Derry, A.M. Meta-analysis supports further refinement of eDNA for monitoring aquatic species-specific abundance in nature. Environ. DNA 2019, 1, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stothard, P. The sequence manipulation suite: JavaScript programs for analyzing and formatting protein and DNA sequences. BioTechniques 2000, 28, 1102–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, C.R.; Uy, K.; Everhart, R.C. Fish environmental DNA is more concentrated in aquatic sediments than surface water. Biol. Conserv. 2015, 183, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J.B.; Sunday, J.M.; Rogers, S.M. Predicting the fate of eDNA in the environment: Sediment interactions and persistence. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 10211–10221. [Google Scholar]

- Shogren, A.J.; Tank, J.L.; Andruszkiewicz, E.A.; Olds, B.; Jerde, C.; Bolster, D. Controls on eDNA movement: Water flow and retention dictate vertical distribution in streams. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 10233–10242. [Google Scholar]

- Furlan, E.M.; Gleeson, D.M.; Hardy, C.M.; Duncan, R.P. A framework for estimating the sensitivity of eDNA surveys. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2016, 16, 641–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jane, S.F.; Wilcox, T.M.; McKelvey, K.S.; Young, M.K.; Schwartz, M.K.; Lowe, W.H.; Letcher, B.H.; Whiteley, A.R. Distance, flow and PCR inhibition influence detection in stream networks: An eDNA case study. Freshw. Sci. 2015, 34, 312–330. [Google Scholar]

- Laporte, M.; Bougas, B.; Côté, G.; Champoux, O.; Paradis, Y.; Bernatchez, L. Dynamics of eDNA in flowing water: Transport, dilution, and resuspension. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2020, 20, 1461–1475. [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox, T.M.; McKelvey, K.S.; Young, M.K.; Lowe, W.H.; Schwartz, M.K. Environmental DNA transport distance is influenced by seasonal variation in flow regimes. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0162494. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, B. Biological analysis of Leiocassis longirostris. J. Southwest China Norm. Univ. Nat. Sci. Ed. 1980, 2, 77–83. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, M.; Wan, Q. The biology and culture prospect of Leiocassis longirostris in the Yangtze River. J. Anhui Sci. Technol. Univ. 2001, 15, 49–51. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Uchida, K. The fishes of Tyosen. Part Nematognathi, Eventognathi. Bull. Fish Exp. Sta. Gov. Gen. Tyosen 1939, 6, 268–271. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, S.Q. Synopsis of Freshwater Fishes of China; Jiangsu University Science and Technology Publishing House: Nanjiang, China, 1995; 549p. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, M.A.; Turner, C.R.; Jerde, C.L.; Renshaw, M.A.; Chadderton, W.L.; Lodge, D.M. Environmental conditions influence eDNA persistence in aquatic systems. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 1819–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, W.; Zhou, J.; Li, Z.; Jing, T.; Zhao, L.; Ye, H. Characterization of 55 SNP markers in Chinese longsnout catfish Leriocassis longirostris. Conserv. Genet. Resour. 2020, 12, 427–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; He, K.; Xiang, P.; Wang, X.; Tong, L.; Wei, Z.; Zhang, X.; Song, Z. Temporal genetic variation of the Chinese longsnout catfish (Leiocassis longirostris) in the upper Yangtze River with resource decline. Environ. Biol. Fishes 2022, 105, 1139–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Mou, C.; Zhou, J.; Ye, H.; Wei, Z.; Ke, H.; Huang, Z.; Duan, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Zhao, H.; et al. Genetic diversity of Chinese longsnout catfish (Leiocassis longirostris) in four farmed populations based on 20 new microsatellite DNA markers. Diversity 2022, 14, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Station | GPS Coordinate | Location | Water Depth (m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| St. 1 | 36°18′58″ N 126°55′56″ E | Buyeo-eup, Buyeo-gun, Chungcheongnam-do | 2.5 |

| St. 2 | 36°17′18″ N 126°54′09″ E | Gyuam-myeon, Buyeo-gun, Chungcheongnam-do | 4.3 |

| St. 3 | 36°15′11″ N 126°54′24″ E | Gyuam-myeon, Buyeo-gun, Chungcheongnam-do | 6.6 |

| St. 4 | 36°14′34″ N 126°57′35″ E | Buyeo-eup, Buyeo-gun, Chungcheongnam-do | 2.6 |

| St. 5 | 36°12′13″ N 126°58′14″ E | Sedo-myeon, Buyeo-gun, Chungcheongnam-do | 5.1 |

| St. 6 | 36°09′59″ N 127°00′16″ E | Ganggyeong-eup, Nonsan-si, Chungcheongnam-do | 3.6 |

| St. 7 | 36°08′58″ N 126°58′15″ E | Yongan-myeon, Iksan-si, Jeonbuk-do | 10.7 |

| St. 8 | 36°08′28″ N 126°55′34″ E | Imcheon-myeon, Buyeo-gun, Chungcheongnam-do | 2.3 |

| St. 9 | 36°07′31″ N 126°52′47″ E | Ungpo-myeon, Iksan-si, Jeonbuk-do | 3.0 |

| St. 10 | 36°04′48″ N 126°52′23″ E | Ungpo-myeon, Iksan-si, Jeonbuk-do | 3.6 |

| St. 11 | 36°02′57″ N 126°50′14″ E | Napo-myeon, Gunsan-si, Jeonbuk-do | 3.4 |

| St. 12 | 36°01′51″ N 126°47′46″ E | Napo-myeon, Gunsan-si, Jeonbuk-do | 7.7 |

| St. 13 | 36°01′35″ N 126°45′43″ E | Seongsan-myeon, Gunsan-si, Jeonbuk-do | 5.0 |

| Station | Quantification Cycle (Cq) Value | Total Volume Equivalent (Copies L−1) | Average | Standard Deviation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Replicate | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| St. 1 | ND | ND | ND | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| St. 2 | ND | ND | ND | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| St. 3 | ND | ND | ND | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| St. 4 | ND | ND | ND | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| St. 5 | ND | ND | ND | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| St. 6 | ND | ND | ND | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| St. 7 | ND | ND | ND | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| St. 8 | 37.78 | 38.06 | 35.04 | 559.9 | 468.4 | 3109.6 | 1379.30 | 1499.18 |

| St. 9 | ND | ND | ND | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| St. 10 | ND | ND | ND | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| St. 11 | 36.85 | 36.12 | 36.16 | 1002.3 | 1577.7 | 1545.9 | 1375.30 | 323.42 |

| St. 12 | ND | ND | ND | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| St. 13 | ND | 36.17 | ND | 0.0 | 1530.2 | 0.0 | 510.07 | 883.46 |

| Station | Quantification Cycle (Cq) Value | Total Volume Equivalent (Copies L−1) | Average | Standard Deviation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Replicate | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| St. 1 | ND | ND | ND | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| St. 2 | ND | ND | ND | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| St. 3 | ND | ND | 36.06 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1638.1 | 546.03 | 945.76 |

| St. 4 | 36.13 | 37.07 | 36.06 | 1572.2 | 872.9 | 1645.7 | 1363.60 | 426.54 |

| St. 5 | ND | ND | ND | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| St. 6 | ND | ND | ND | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| St. 7 | ND | ND | ND | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| St. 8 | ND | ND | ND | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| St. 9 | ND | ND | ND | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| St. 10 | ND | 35.93 | 35.08 | 0.0 | 1787.2 | 3042.6 | 1609.93 | 1529.03 |

| St. 11 | ND | ND | ND | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| St. 12 | 34.95 | ND | ND | 3296.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1098.80 | 1903.18 |

| St. 13 | 34.68 | ND | ND | 3893.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1297.77 | 2247.80 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hong, C.G.; Kim, K.Y.; Heo, J.S.; Choi, B.H.; Park, J.H.; Kim, S.Y.; Yang, S.G. Molecular Monitoring of Leiocassis longirostris Using Species-Specific qPCR Assays from Environmental DNA. Animals 2025, 15, 3451. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233451

Hong CG, Kim KY, Heo JS, Choi BH, Park JH, Kim SY, Yang SG. Molecular Monitoring of Leiocassis longirostris Using Species-Specific qPCR Assays from Environmental DNA. Animals. 2025; 15(23):3451. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233451

Chicago/Turabian StyleHong, Chang Gi, Keun Yong Kim, Jung Soo Heo, Bo Hyung Choi, Ju Hwan Park, Seung Yong Kim, and Seo Gyeong Yang. 2025. "Molecular Monitoring of Leiocassis longirostris Using Species-Specific qPCR Assays from Environmental DNA" Animals 15, no. 23: 3451. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233451

APA StyleHong, C. G., Kim, K. Y., Heo, J. S., Choi, B. H., Park, J. H., Kim, S. Y., & Yang, S. G. (2025). Molecular Monitoring of Leiocassis longirostris Using Species-Specific qPCR Assays from Environmental DNA. Animals, 15(23), 3451. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233451